In the spirit of reconciliation, Honeywell acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of Country throughout Australia and their connections to the land, sea and community. We pay our respect to Elders past, present & emerging and embrace the continuation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their cultural and spiritual practices.

Deceased Persons Warning

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that the following pages may contain images of people who have passed on.

2 Richardson Place, North Ryde

The Inception Strategies team toured the new Honeywell office development at 2 Richardson Place.

During these early conversations, we were inspired by Honeywell staff’s love of the great outdoors, including the big skies that are visible in regional and remote areas of NSW and Australia.

The local Aboriginal Group for North Ryde is the Wallumedegal peoples.

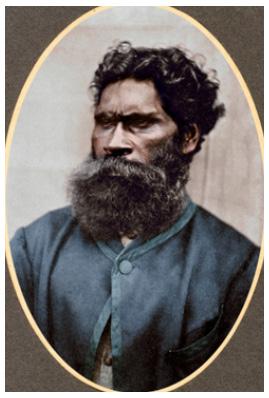

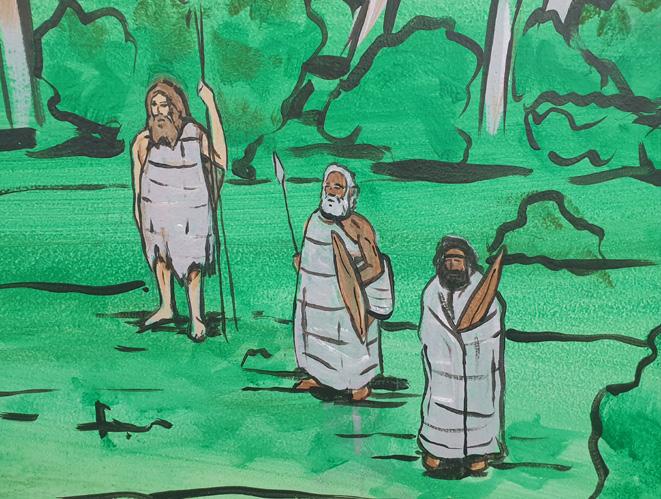

“The Ryde area was known as the place where the clever men would meet. The clever men, or Koradgi in the Darug tongue were believed to have special powers and could visit the sky country - the abode of the ancestors and home of the sky father Biami.” Chris Tobin

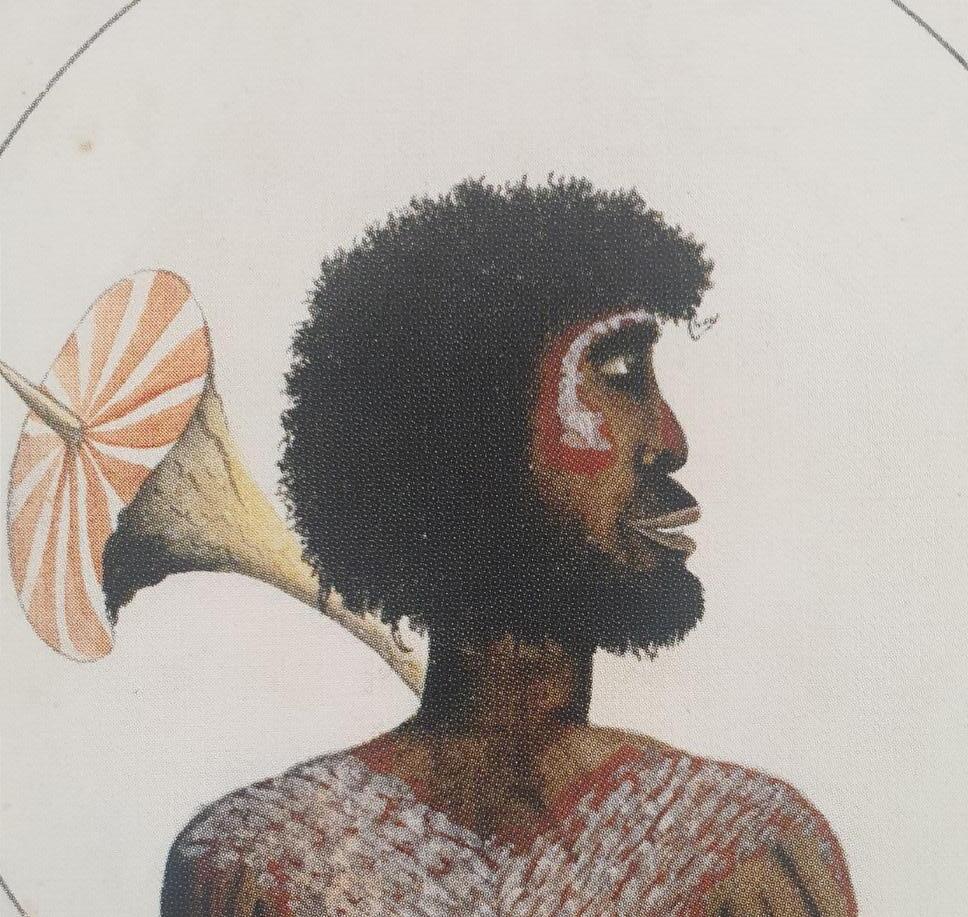

Aboriginal Clever men sometimes made emu feather shoes for themselves so they could not be tracked. This added greatly to people’s fear about them as men who could appear from nowhere and disappear just as quickly.

Progressing with the theme of Sky Country, our team carried out further research to identify insights that could inform the artwork process.

Insight 1:

Aboriginal people view the sky, land and waters as a single, connected Country and not as separate domains. Moreover, Aboriginal people made cultural connections between star positions and the availability of animals, fruits and plants that were part of the Aboriginal diet.

When

Insight 2:

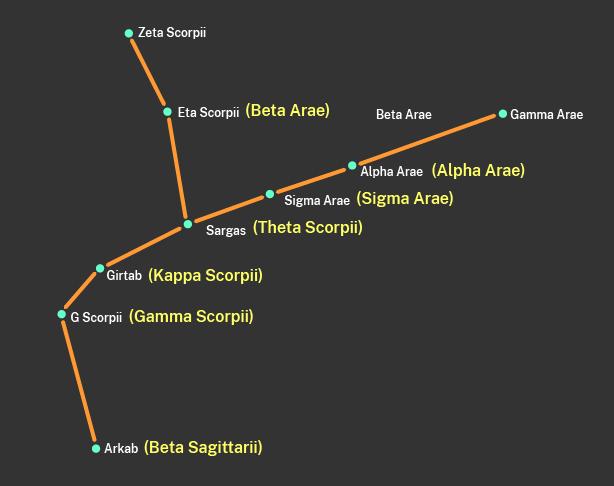

Aboriginal people used the stars as a cultural library. For example, the position of certain stars provided navigational star maps that Aboriginal people could use to travel accurately at night over long distances.

Travelling at night could be helpful as it requires less water and provides an opportunity for people to recharge and rest during the day for the warmer summer months.

The Pleiades cluster forms the Seven Sisters dreaming story: as seven young women running away from a man. Miyay-Miyay were known by Aboriginal peoples as ‘ice maidens’ because the position of them was connected with frosts on land. In some stories, they are chased by a single man, whilst in others they are chased by boys called Birray-Birray that make-up the Orion star cluster.

The original wall is approximately three by four metres at the rear of a carpeted office. Lighting is by two overhead fluorescent lights.

My mother is English and father English/Gomeroi from the Guyinbaraay clan of the Gomeroi nation from the Gunnedah area NSW.

I currently live in Lismore, NSW. I grew up in Glen Innes, NSW and have been obsessing over art since I was young. I was/am a MAD magazine fan and loved the artwork of Mort Drucker and Sergio Aragones and used to love looking at the lines and cross-hatching in their drawings. I mainly use water-colour, ink and pen. I really enjoy the human face and this is the subject matter of most of my artworks, but I also do traditional works and incorporate traditional symbols/themes into them. I also enjoy using layers in my art and creating works using text and colour which you can look at and find new things that you might not have seen before.

I have lived and worked in Japan for a total of ten years, during which time I was lucky to be chosen for the NIKA Art and Design Awards for three years in a row and my works were exhibited at the National Art Centre, Tokyo. More recently, I now have my work is exhibited at Bromley and Co. galleries in South Yarra and Daylesford, Victoria.

Here, Nathan is adding Aboriginal bush iconography to the mural including kangaroos, emus and people. Also visible are stars in the night sky that will be further expanded upon in the next part of the painting.

Nathan Sky Country

Acrylic on gyprock

Provenance: Honeywell Commission

Centre star wheel reminds us that stars shift their position throughout the night and that these movements are important to Aboriginal people who used them to plan cultural activities on the ground such as food gathering.

Human figures featuring on the left and top right of the artwork represent ancient Aboriginal star stories such as the chase of the Miyay-Miyay, young women (Pleiades cluster) by Birray-Birray, young men (Orion cluster).

Ground layer contains fire, trees, water, land and animals that are all important elements of Aboriginal Country. The blue circled areas on the ground are star reflections embedded in Country to help the viewer understand how Aboriginal people viewed sky, land and waters as one interconnected, cultural way of life.

Smith (2005) Wallumedegal - an Aboriginal History of Ryde, City of Ryde

Aboriginal Koradgi Shoes via Daderot, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Napoli and Noon (2022) Indigenous Ways of Knowing in Sky Country, pp 1-61

University of Melbourne (2023) Indigenous astronomy, geography and star maps, Indigenous Knowledge Institute

2 Richardson Place, North Ryde, NSW

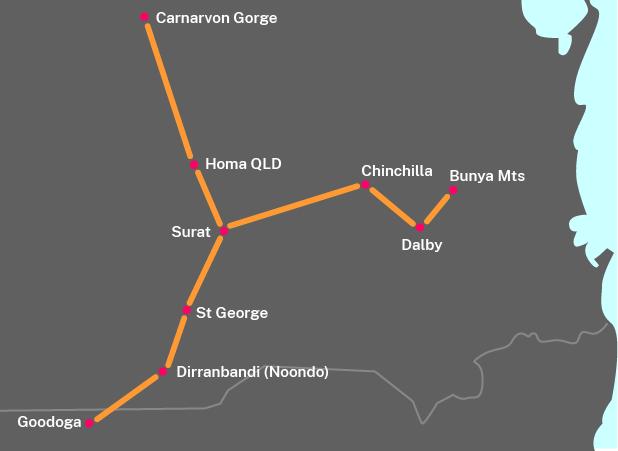

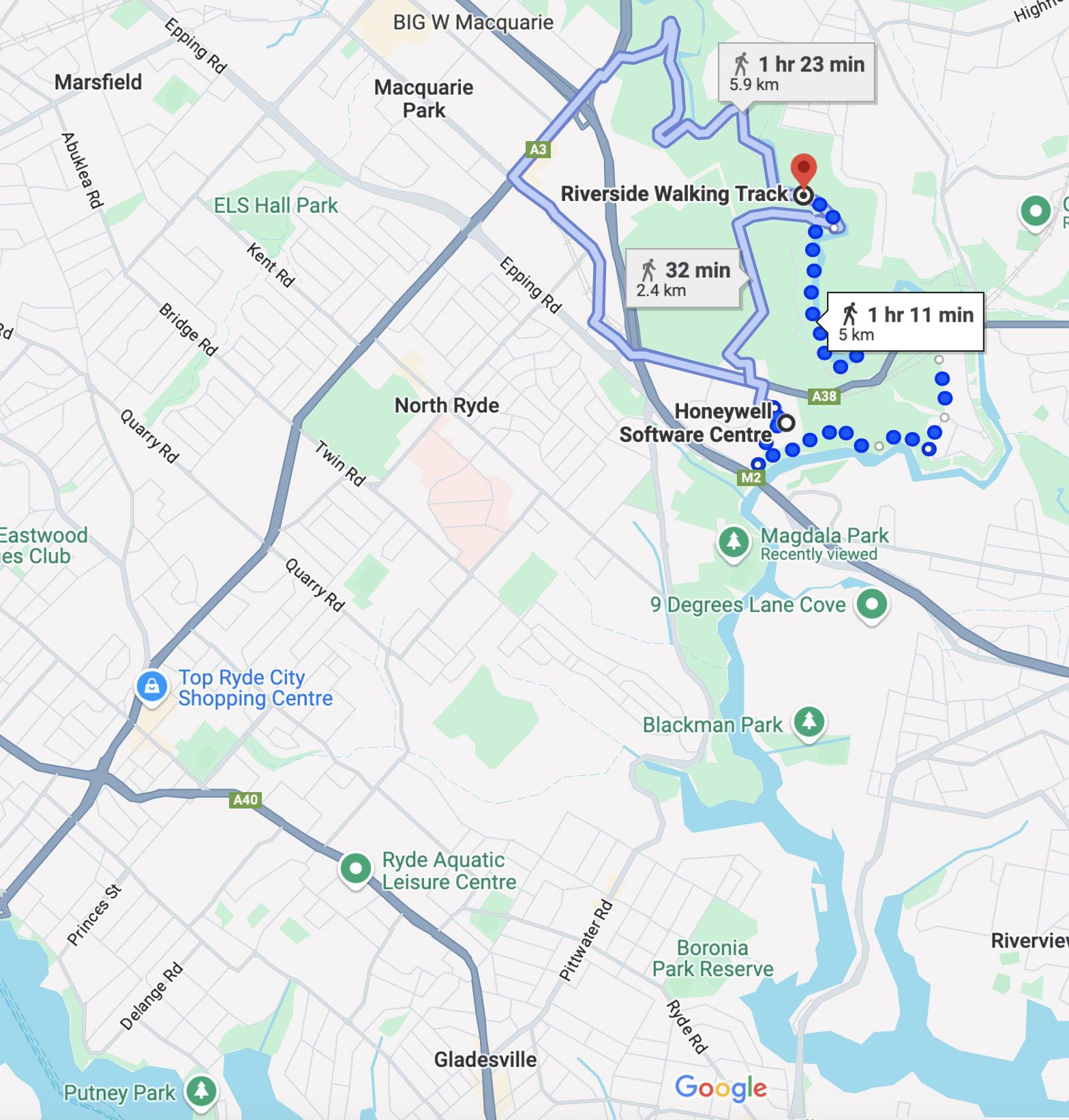

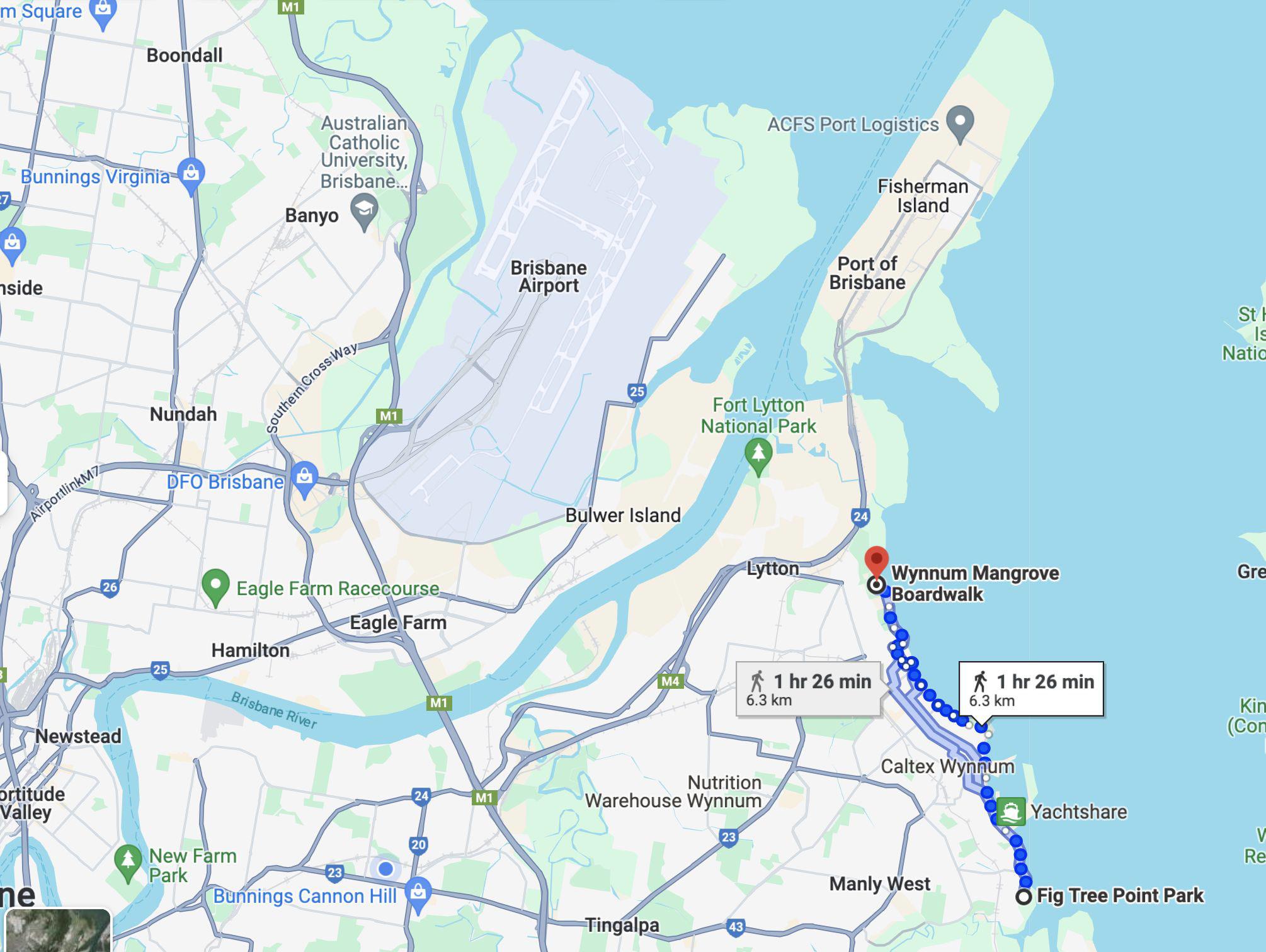

Honeywell’s North Ryde Software Centre is located near the Lane Cove river that flows into Sydney Harbour from Lane Cove National Park. According to our research, the name Wallumedegal or Wallumatta peoples originated from Wallumi, the Aboriginal name for a snapper fish combined with matta that was a name for a place with water, ie Parramatta, Cabramatta. Putney Park, at the bottom left of this map was a significant place and home of the Kissing Point tribe of the Wallumedegal.

Nathan Dawson is a Gomeroi man from the Guyinbaraay clan from the Gunnedah area of NSW.

Nathan mainly uses water-colour, ink and pen.

Nathan has lived and worked in Japan for a total of ten years, during which time he was chosen for the NIKA Art and Design Awards for three years in a row and his works were exhibited at the National Art Centre, Tokyo.

Nathan presently lives in Lismore, NSW with his wife and 4 children.

Nathan Dawson in front of his Ballooderry Mural for the Honeywell Software Centre, North Ryde office

Ballooderry’s family life began in what is now called Parramatta. He was the son of a prominent Burramattagal leader Maugoran and his wife Gooroobera. Ballooderry’s name came from Baluderi which meant ‘leatherjacket fish’ and he had a younger brother Yeranibi and sister Abaroo.

The arrival of the first fleet was a shock to Ballooderry and his family’s way of life. European settlers moved into the prime farmlands around the Rose Hill area in Parramatta and forced Ballooderry and his family to move in an easterly direction down the Parramatta river to Kissing Point. Rather than take up an active resistance, Ballooderry decided to befriend the Europeans and was curious about their way of life. Lieutenant David Collins remarked about Ballooderry:

“nowhere had we seen a finer young man”

According to colonial chronicler, Lieutenant General Watkin Tench, Ballooderry helped the Europeans trace the route of the Hawkesbury River, as there was confusion amongst the visitors whether the Hawkesbury was the same as the Nepean river or separate?

Less concerned with map-making, Ballooderry was nervous about travelling so far from Parramatta and Kissing Point, being acutely aware of the danger of crossing into Country of the inland tribes without obtaining cultural permission.

Ballooderry’s fishing skills made him a popular guest and Governor Philip provided a small hut for him to sleep in at the Governor’s property. Ever conscious of the political dangers of extravagance, Philip suggested to Ballooderry that he could perhaps also make a business out of catching fish for other people in the colony.

Warming to the idea, Ballooderry crafted his own canoe and established a brisk trade by transporting caught fish from Aboriginal communities living at the heads of Sydney Harbour and selling them for European food and goods at Parramatta. A tremendous feat of stamina considering that the water distance is nearly 27km each way. For example, even if Ballooderry met the coastal communities to exchange the fish at a half-way point he still would have had a 13-14 km paddle in a canoe heavily laden with fish. It’s also highly likely that Ballooderry would have covered the fish with paperbark or similar to stop them spoiling in the sun.

After just three weeks of running his business, some jealous and envious convicts entered Ballooderry’s family land at Kissing Point and deliberately sank Ballooderry’s canoe. A tragic event for Ballooderry that not only ruined his business but also involved a cultural loss of face and reputation, as the canoe’s destruction may have made it difficult for Ballooderry to pay his coastal community fishermen at Sydney heads for their hard work, making him personally subject to unfavourable and potentially dangerous cultural reprisals or payback.

Taking matters into his own hands, Ballooderry painted himself for war and gathered his spears. Governor Philip warned him against taking action whilst reassuring him that British law will bring the offenders to justice. Soon afterwards, two men were caught with one receiving a flogging and the other one was hanged. Regardless of the punishments, Ballooderry, had now unfortunately lost confidence in the Europeans to do the right thing. So, when he caught another European man sneaking around Kissing Point a few days later, he coiled with rage and speared him.

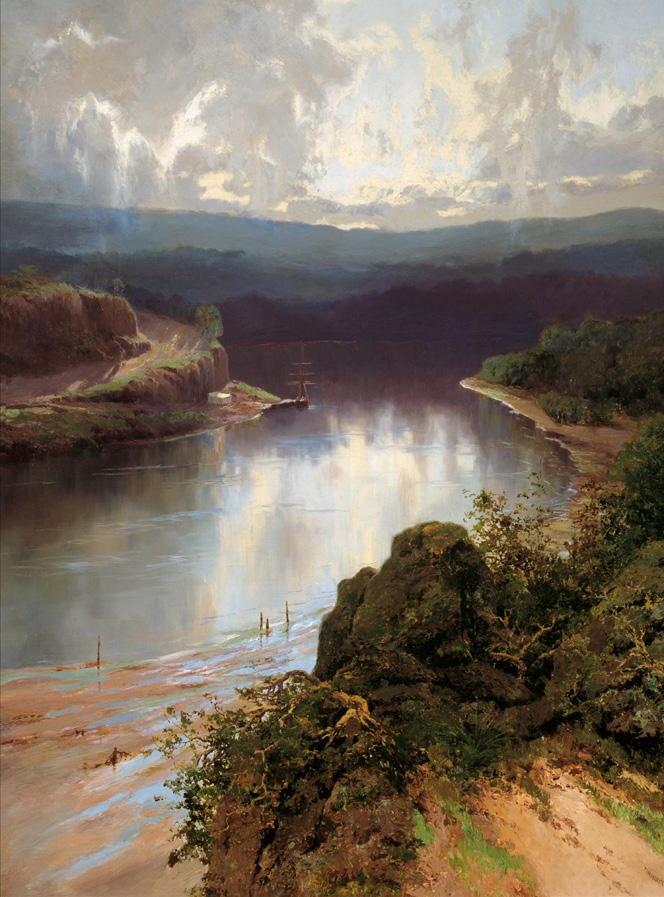

Governor Philip was incensed at Ballooderry’s act and gave orders that Ballooderry be shot on sight. Ballooderry retreated deep into the Country he knew so well and stayed one step ahead of his pursuers for years. The painting (to the right) of Lane Cove river might have been Ballooderry’s view of Europeans using the river, while he remained careful to keep a safe distance.

Diamond Python, 1788, painter unknown. Diamond Pythons are generally harmless, but if highly agitated will strike.

Ballooderry eventually fell very sick and was canoed into Governor Philip’s house and admitted into Sydney hospital where he was treated by Philip’s own doctor and also an Aboriginal clever man but sadly died a few days later.

“The wedgetail Eagles in the centre right of the painting represent freedom, connection to Country and are significant to my people.”

Artist Nathan Dawson

Ballooderry had intimate knowledge of the river systems of Sydney including the Lane Cove river that is near the Honeywell office. As one of the first Aboriginal entrepreneurs of the early colony, Ballooderry saw the power of connecting two communities together with the establishment of his business. The story of Ballooderry is unique in Aboriginal history and to the best of our knowledge, the Ballooderry Mural in the Honeywell Software Centre is the only painted representation of his story in NSW.

Ballooderry was buried inside a canoe with his fishing spears and possum skin jacket in the garden of Government House in Sydney which is now the site of the Museum of Sydney. Ballooderry’s funeral was the very first cross-cultural funeral in the history of the colony that was attended by senior members of both the Aboriginal and colonial communities.

City of Paramatta have established a Ballooderry (Baludarri) Wetland immediately west of James Ruse drive on the northern bank of the Parramatta River. The site is bounded by:

• Thomas Street to the north;

• James Ruse Drive to the east;

• Pemberton Street to the west, and

• The Parramatta River to the south.

Parramatta Council (2010) Baludarri Wetland Plan of Management

Smith (2005) The Wallumedegal: An Aboriginal History of Ryde

Beck Jeffrey (1899) Admiral Phillip; The Founding of New South Wales

19 Corporate Drive, Cannon Hill

Aboriginal people in the Cannon Hill area would have regularly visited Brisbane River and also the Coast for food gathering. The Inception Team did some site walking along the mangrove coastline from Manly up towards Fisherman island that was significant for the Turrbal Aboriginal peoples living south of the Brisbane river. Crabs were caught at low tide with a hooked stick by Aboriginal people who could easily recognise an ‘inhabited’ hole by the markings around it. The caught crabs would be carried in a dilly bag along with carefully included mangrove twigs that kept the crabs calm so they would not fight against other crabs or the bag.

The feature wall is 3.25 by 3.45 metres and is located immediately on the left as you walk into the Honeywell office area after checking in at Reception.

Corroborees were ‘mega events’ held by large groups of Aboriginal people (up to 500) that came together to exchange news, dance, culture and family ties with other groups when food was plentiful in the Brisbane river region.

“it was a grand sight to see 300 men at a time dancing in and out, painted all colours”

Petrie (1837)

Turrbal peoples of the Brisbane region often engaged in serious games when the working part of the day was done. One of these games was called Mamtchi or Black Swan and involved a person in front (the swan) who would be chased by the hunters who could catch the swan by a light tap on their skin. Whilst such games might seem like a simple water based version of tag, there were important reasons why they were played by Aboriginal young people and adults. In coastal regions, where survival meant being able to quickly and effectively catch food sources, such water based play reinforced skill development, strength, dexterity and speed that made life on the river and coastal waterways easier, more sustainable and efficient for Aboriginal people.

The Turrbal people had special men called Turrwan. Turrwan might dance at a Corroboree, but they may also be called upon to do a great number of other services for a mob such as changing the weather, healing the sick and even investigating a murder. Each Turrwan was an experienced and highly respected member of his group and would usually be known for having a particular strength in one area. A Turrwan, was said to draw his power from a rainbow spirit personality called Taggan who sent the power to a Turrwan via a quartz crystal that was dived for in deep & clear pools.

by Nathan Dawson

In the centre, Aboriginal children play the ‘Black Swan’ water tag game known as Mamtchi. On the left, a senior Aboriginal Turrwan practices his Corroboree dance whilst wishing the children below to ‘fly far’ and have a long and healthy life like the swans flying above. Meanwhile, on the far right, an Elder is being transported to Fisherman Island in a canoe to live on Dugong to support their safe and strong return to the Community.

Aboriginal artist of the Honeywell Brisbane Mural, Nathan Dawson, is a Gomeroi man with family connections in Brisbane and Queensland.

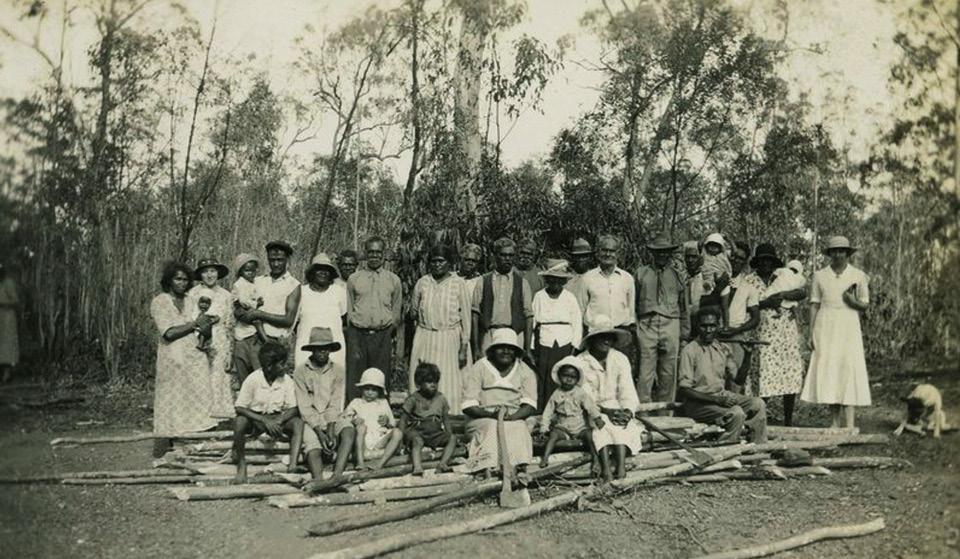

The co-owner of Inception Strategies, Elsie Amamoo, was born in Cherbourg, formerly known as Barambah Mission - the place where many Turrbal peoples were relocated after their forceful removal from Brisbane in the early 1900’s.

Petrie (1904) Reminiscences of Early Queensland

Folkmanova (2015) The oil of the Dugong: Towards an Indigenous History of Medicine

Kane, Kerkhove, Memmott (2022) Aboriginal Places of Inner Brisbane, University of QLD

Honeywell’s Perth office in Rivervale is near the Swan River.

The Burswood Peninsula (below centre) is located inside the Beeloo Aboriginal region, an area bounded by the Canning River in the south, Melville Water in the west, the Swan River and Ellen Brook in the north and the Darling Range to the east.

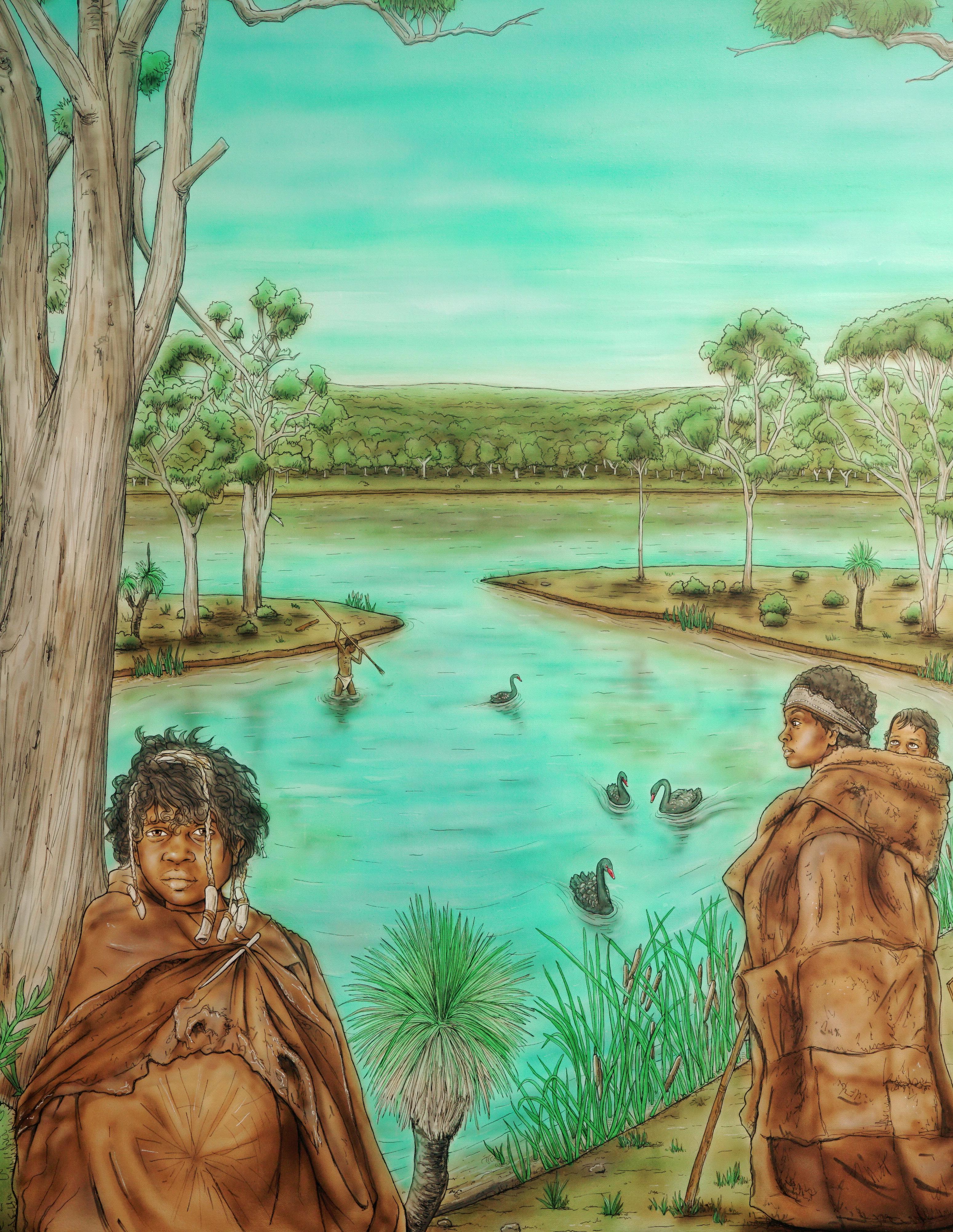

The Beeloo people are a sub-group of the Whadjuk peoples who lived in the Swan River area that included low-level wetlands and swamps teeming with birds, fish and trees. The area around Heirisson Island (bottom left) was also known as Matagarup or ‘knee deep’ to the Noongar Aboriginal people, who would choose it as a place to cross the Swan river.

Nathan Dawson is a Gomeroi man from the Guyinbaraay clan from the Gunnedah area of NSW. Nathan mainly uses water-colour, ink and pen. Nathan has lived and worked in Japan for a total of ten years, during which time he was chosen for the NIKA Art and Design Awards for three years in a row and his works were exhibited at the National Art Centre, Tokyo. Nathan presently lives in Lismore, NSW with his wife and 4 children.

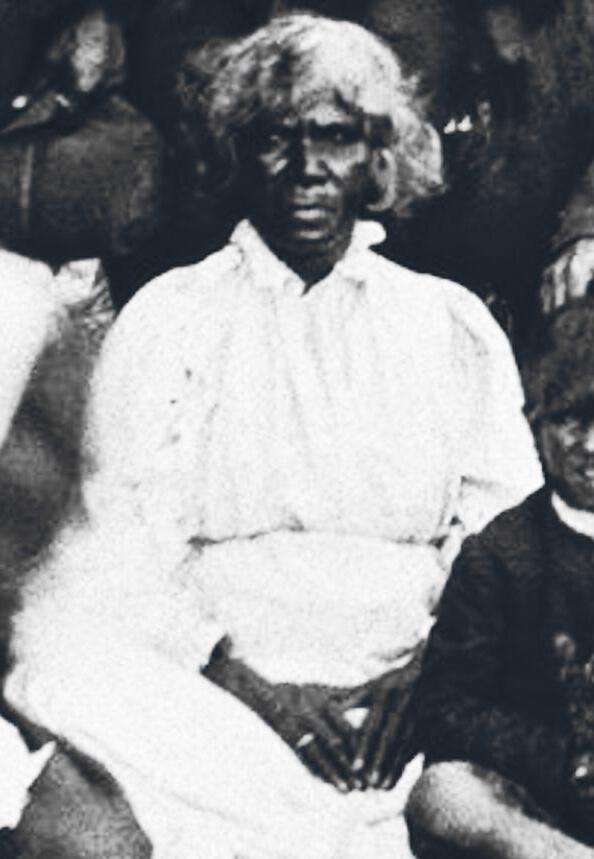

Balbuk was born on Heirisson Island in 1840. Her father was Goondebung and her mother, Joojebul, was born on a nearby island called Yoonderup, located at the tip of the Burswood Peninsula - but is now connected to the land.

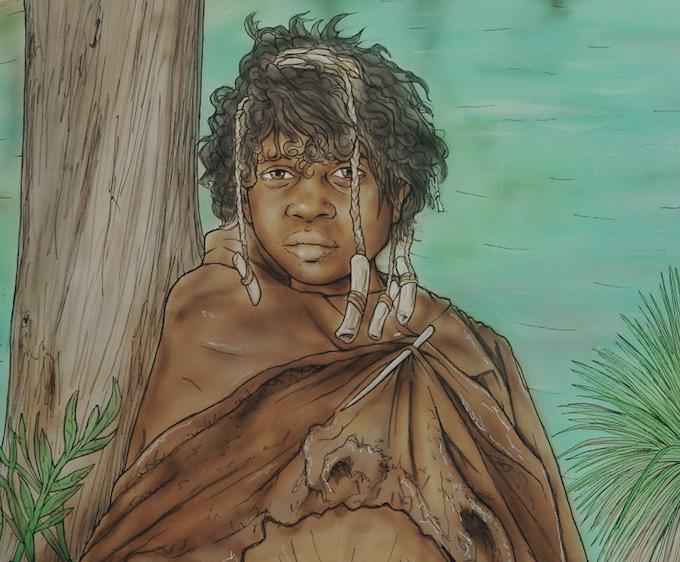

One of Balbuk’s early responsibilities would have been gathering By Yu, the Aboriginal name for the fruit of the Zamia Palm (right). Zamia was known as Djiriji or Girijee to the Noongar people with flowers that look like pineapples.

Balbuk would have gathered By Yu and stored it in a kangaroo skin bag. Then Balbuk would have taken the By Yu to a processing place where the bright red, flesh-covered seeds would be buried in watery ground for up to four weeks to leach out the poisonous chemicals, after which her family could eat the delicious red fleshy part but not the seed. If water was in short supply, By Yu could be buried in dry ground with leaves from the grass tree (see below right). If water was plentiful, By Yu could be placed under the mud in a fish trap to stun the fish and make the process of collecting the fish much easier.

While By Yu would have been gathered by Balbuk in March each year, as the months progressed, different plants would come into season. One that Balkbuk would have harvested in April and May, was the root of Yanjidi or Bulrush river plant. Balbuk would have looked for Yanjidi after a recent rain making the ground easier to dig with her Wanna or special purpose Aboriginal digging stick that was fire-hardened to a flat point at one end.

‘The (Aboriginal people) dig the roots up, clean them, roast them, and then pound them into a mass, which, when kneaded and made into a cake, tastes like flour not separated from the bran.’

(George Fletcher Moore 1842)

Carbohydrate rich, cross section of the Yanjidi root harvested by Aboriginal women in the Swan River area

Balbuk’s parents married her to an Aboriginal Tondarup man called Domkin from Fremantle. After his death, Balbuk was given to Domkin’s brother, Burtap, as was the custom. However, Balbuk did not like her new husband and many times fled into the bush hoping to be rid of him. Each time, she was dragged back by Burtap’s family until they tired of retrieving her and she escaped further inland to the Northam area.

Balbuk promptly fell in love with a Narganook man called Kraggo and married him in a union that may have been illegal using their kinship system because his skin family, Narganook, was part of the same wider family of Balbuk’s, the Ballaruk. This led to a terrible argument with Kraggo’s sister that ended up in a fight and the accidental death of the sister. Fearing cultural payback, Balbuk fled whilst being pursued.

For a period of seven years, Balbuk travelled through the Moore River and Murchison areas spending time with her extended family relations at both places. At Moore River, Balbuk entered into her 4th marriage with a Tondarup man who was the proper skin group and had her first child called Mowerr. Sadly, Mowerr died whilst still a toddler.

Having served her ‘voluntary banishment’ of seven years, Balbuk returned to the Swan River area and found that most of her Country had been overtaken by the Europeans. Without a place to stay, Balbuk was forced to work as a domestic in some of the colonial homes, looking after their children. A task that might have been healing on one hand, given she had lost her own child and difficult on the other, because Aboriginal ways of childcare were different to the European customs, meaning that she may have suffered some criticism for using her own style.

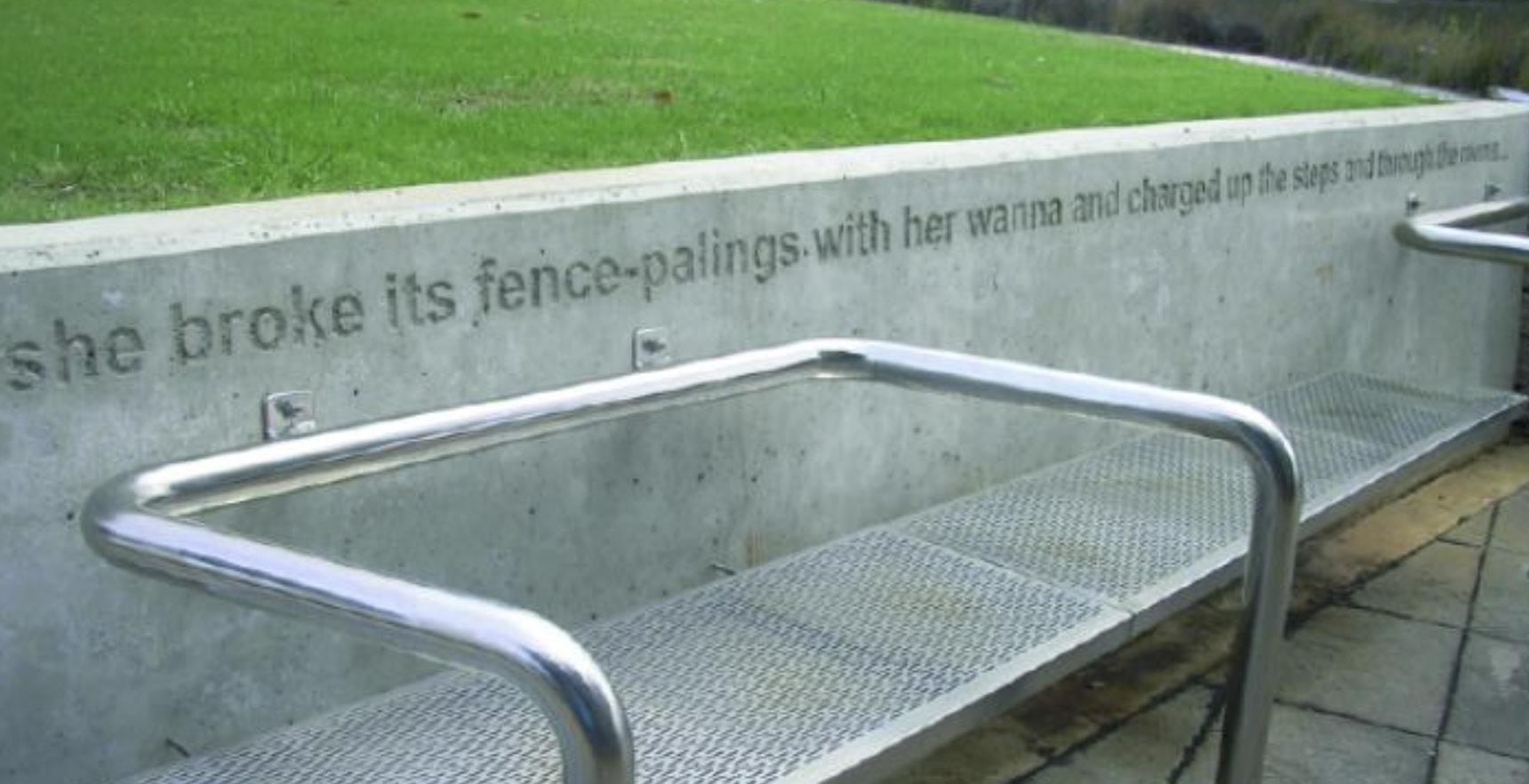

As the attraction of domestic service wore off, Balbuk found herself with more freedom and flexibility, preferring the company of an Aboriginal man by the name of Dool. Soon, both of them acquired a taste for bread & beer and sometimes this would get Balbuk into hot water as she would partake in her famous ‘straight-line walking’ through the settlements using her traditional walkways. Including, walking through fences and also the houses that had subsequently been built on her lands whilst unleashing a tirade of criticism and protest such as ‘My grandmother is buried there, why is your house on her?’ and others.

Behaviour, that often landed her in lockup, but as the government officials in charge of the police and detention were formerly the children that Balbuk had nursed and supported as toddlers, they would end up paying her fines themselves and released her.

Although Balbuk was an eccentric and occasionally polarising character in the early days of the Swan River community, she was always careful not to break her totem food laws and never failed to perform the customary cultural acknowledgements to Waugyl the creator serpent and the spirits in the rocks, caves and hills.

‘Balbuk knew every sacred totem spot and the spirits that lived there from the mouth of the Swan to the ranges.’

Most of the Whadjuk people from Beelo were moved into a nearby mission called Maamba in the present-day Forrestfield/Wattle Grove area including what is now Hartfield Park. When Balbuk lay dying in her shelter at Maamba, a female kangaroo, her totem, appeared and Balbuk said ‘My borrunggur has come for me - I go now’ and died a few days later.

On 8th June 2022, the government of Western Australia installed a commemorative sculpture of Balbuk with her wanna or digging stick at Government House, one of the only commemorative sculptures of an Aboriginal woman in Australia.

Commemorative sculpture of Balbuk at Government House (Perth)

Fletcher Moore (1934) Diary of an Early Settler in WA

Macintyre & Dobson (2023) The ancient practice of Macrozamia pit processing

Macintyre & Dobson (2023) Typha root: an ancient nutritious food in Noongar culture

Bates D (1907) Fanny Balbuk Yoreel: The last Swan River female native, The Western Mail

45 Grosvenor St, Abbotsford

The Inception team did some walking along the Yarra River trail and found a lush, wooded river environment.

During the summer months, Aboriginal people moved to the plains, rivers and coast. Along the Yarra, men hunted kangaroo, possum, emu, bush turkey, fish, eels, snakes, water rats, frogs and platypus. Fishing was carried out from bark canoes, cut and shaped from the river red gums; or by spearing fish from the riverbanks. Eels were captured in stone traps or others woven from rushes.

Women hunted small animals and gathered edible plants, berries and shellfish providing up to two-thirds of the clan’s diet. Vitally important to Aboriginal wellbeing were the roots of various plants, including the tubers of the murnong (yam daisy) that were later decimated by sheep and cattle grazing. Other plants provided medicines, fibre for weaving and utensils. Women also made clothing from animal skins, stitched together with animal sinew. Possum Skin cloaks were highly prized.

The feature wall is 4.7m x 2m and located in a prominent area immediately outside the Honeywell staff lunchroom and deck that overlooks the Yarra River.

Nathan Dawson is a Gomeroi man from the Guyinbaraay clan from the Gunnedah area of NSW. Nathan mainly uses water-colour, ink and pen.

Nathan has lived and worked in Japan for a total of ten years, during which time he was chosen for the NIKA Art and Design Awards for three years in a row and his works were exhibited at the National Art Centre, Tokyo.

Nathan presently lives in Lismore, NSW with his wife and 4 children.

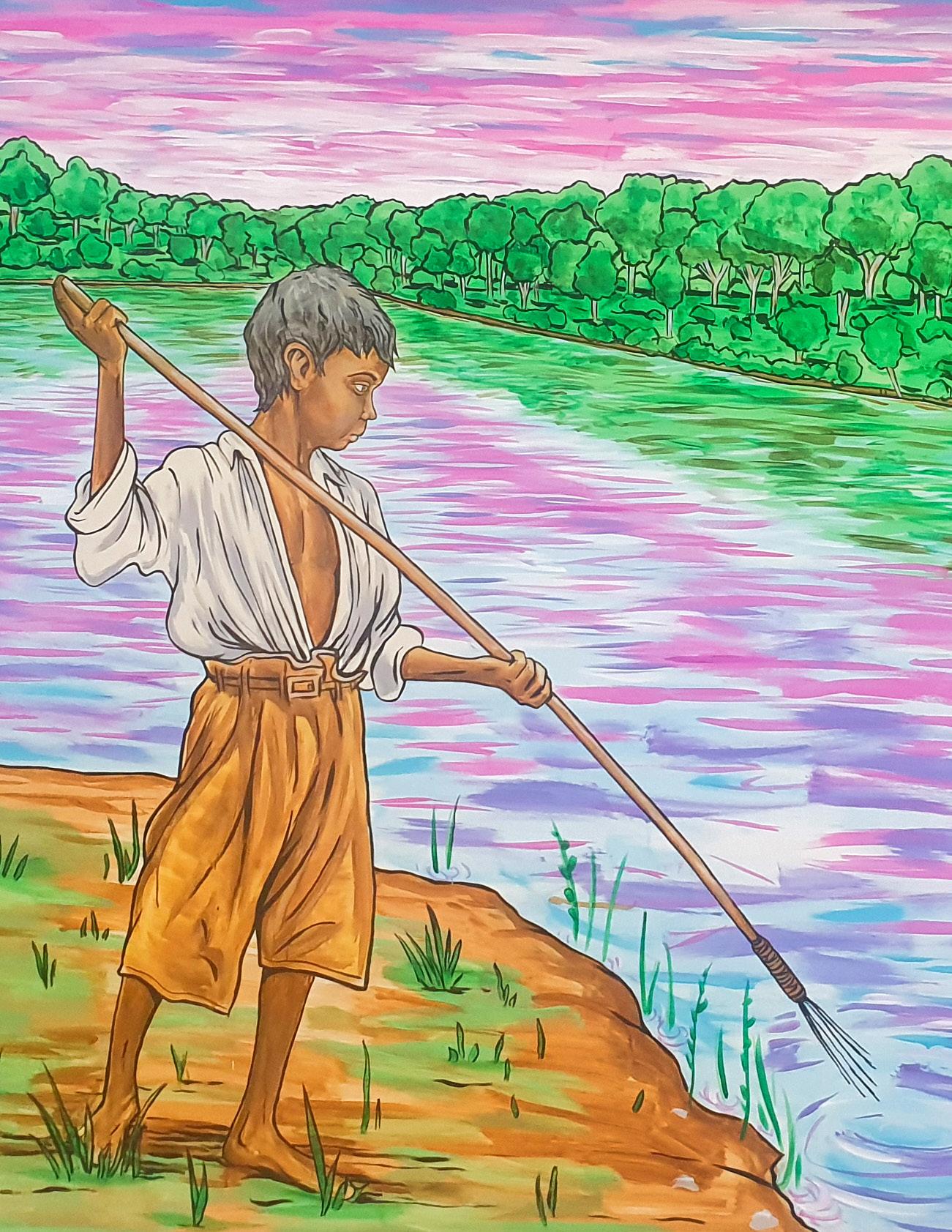

William Barak was born in 1823 at Brushy Creek, an offshoot from the Yarra River, as a member of the Wurundjeri clan group who were part of the Woiwurrung peoples.

Barak’s father was an important Aboriginal leader for the Woiwurrung in the Heidelberg region of the Yarra. Barak’s mother Tooterrie was from the Goulburn river region at Murchison and gave Barak the tribal name of ‘Beruk’.

Victoria has five Aboriginal groups surrounding Melbourne: Woiwurrung, Boonwurrung, Taungurong, Djadjawurung and Wathaurong together make up the Aboriginal ‘Kulin Nation’.

Each tribe has a chief who directs the group’s movements and there are a number of other senior roles including; warrior, counsellor, doctor, dreamer and sorcerer. Women are important in the clan groups and are consulted regarding strategic decisions including ceremonies, initiation and marriage arranged between tribes.

In this picture, Barak is about 11 years old (1834) and is hunting fish for dinner. Later, at the age of 13, Barak was given the cultural symbols of manhood including possum skin around his biceps, reed necklace, nose peg and a waist string.

When Barak was 19, he joined the Native Police Corps and it was then his name changed from Beruk to William. Native Troopers like Barak helped to police the Yarra River area. Barak became known as a talented tracker with skills in demand for years after he left the Native Police Corps.

For example, Barak was often engaged in tracking missing children and thieves on the run including once, the notorious bush outlaw - Ned Kelly and his gang as per the following:

Pointing to the woodland down below, Barak turned to the senior policeman, “Robbers (Kelly and his gang) are in there – go get them.” The head policeman replied “You go in first, we’ll follow.” Barak bristled “I have no gun, I track.”

So the police decided instead to send for reinforcements and the Kelly gang escaped.

Trackers like Barak could spot a drop of blood on a blade of grass, or tell what sort of horse had gone by and whether it had a rider. He could distinguish even between the sort of boot heels a fugitive was wearing.

As he grew older, Barak became an important source of Aboriginal cultural knowledge, painting Corroborees and helping people to understand what life was like in the early 1800’s, before Europeans arrived. Below, Barak explains how the Yarra River was formed:

Two boys walked up to a wattle tree in search of some wattle gum they liked to eat. One of the boys climbed up to the top of the tree to get some and threw it down to the other boy, but when the wattle gum struck the ground it disappeared. The boy on the ground looked everywhere, confused about where the wattle gum had gone and eventually found a small hole in the ground and poked his spear into it. A loud rumbling voice came back and the ground shook. An old man who had been sleeping underground emerged and snatched the boy, carrying him off into the bush, leaving a trail in the soil because the boy was heavy.

Bunjil the creator, heard the boy cry out and felt sorry for him and decided to put very sharp stones in front of the old man who tripped, fell into them and was cut to pieces whilst the boy rolled safety onto dry grass.

Before the old man died, Bunjil the creator appeared and said to him

“let this be a lesson to all old men, they must be good to children”

Bunjil then turned to the furrow in the ground left by the old man and made it deeper, filling it with water and growing it into the Yarra River.

On the opposite river-bank of the mural (in Barak’s future), we can see a fair-skinned man in a possum-skin cloak by the name of William Buckley. At six foot six, Buckley was a convict who had escaped in 1805 from Tasmania to Melbourne at the age of 23yrs. On the run from police, Buckley’s two co-convicts succumbed to sickness leaving him on his own. Fearing for his life, Buckley chanced upon an Aboriginal grave site and found a spear lying next to it which he took to protect himself. Soon afterwards Buckley, passed out in the bush very unwell and was discovered by two Aboriginal women who had the men carry him back to their camp. Buckley was fed eel and packed with warm possum skins to recover from his fever by the Aboriginal women whilst the community debated what should be done with him.

The spear Buckley had with him was identified as belonging to a highly respected man ‘Murrangurk’ and the community assumed that Buckley was Murrangurk, who had returned to them and was duly accepted into the family hut. Buckley recovered and learned to hunt eels, spear fish and observe Aboriginal cultural traditions and later became an interpreter for the settlers.

A young Barak saw Buckley as a tall, white man dressing like a ‘black-fella’ in a possum-skin cloak, living and hunting in harmony with the community.

Victorian Collections “Life of Barak”

https://victoriancollections.net.au/stories/william-barak/life-of-barak

Simons R (2020) Researching Indigenous Australians

https://www.coursehero.com/file/87408880/Assignment-1docx/

Wiencke (1984) When the wattles bloom again: The life and times of William Barak, last chief of the Yarra Yarra tribe.

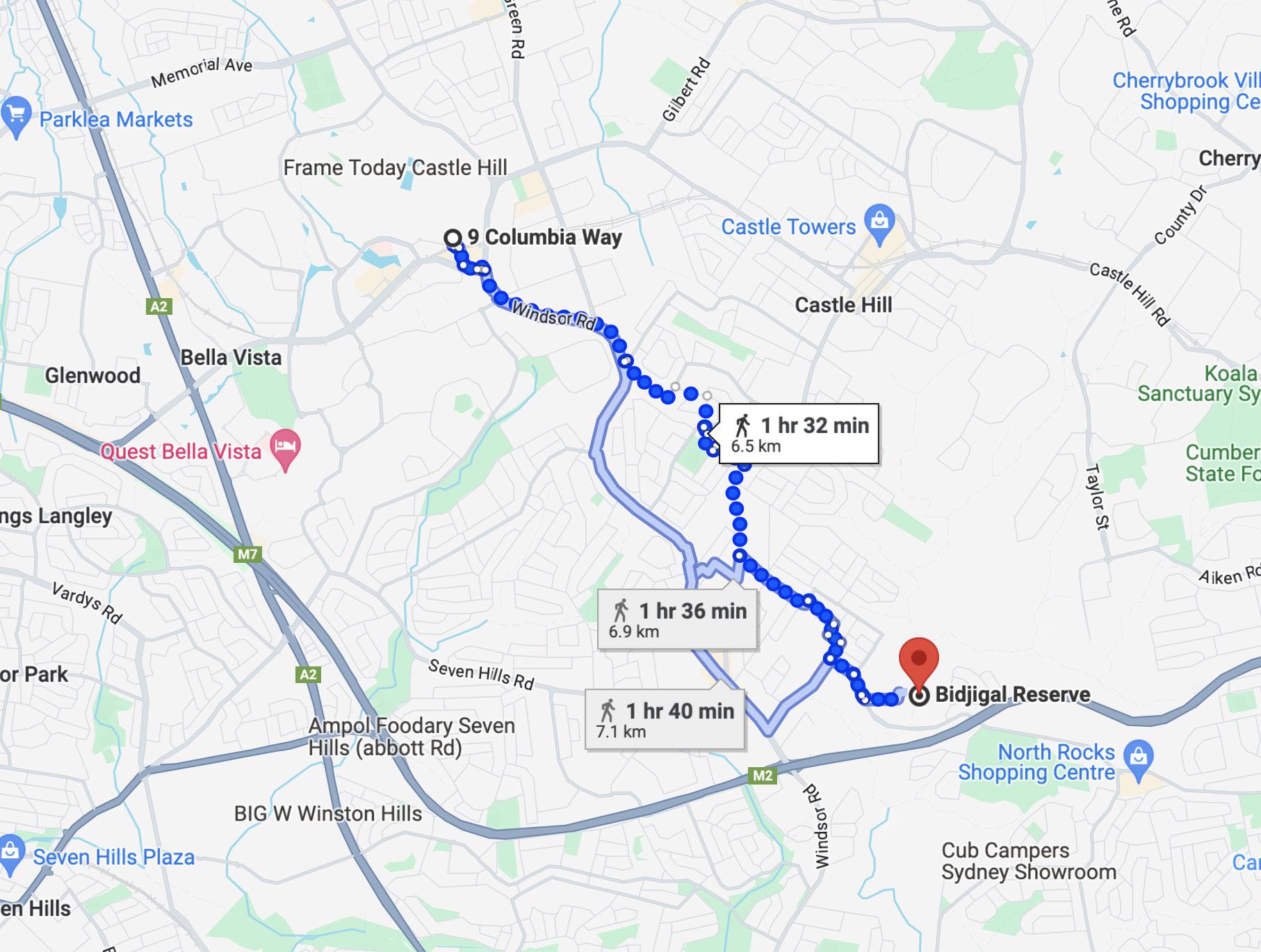

9 Columbia Way, Baulkham Hills, NSW

The Honeywell Baulkham Hills office is situated next to ‘Strangers Creek’, a water source that links with the Hawkesbury River in a North-Westerly direction at Cattai National Park which was an important source of food for the Dharug people. In the other direction, to the South East, the Honeywell Baulkham Hills office links with ‘Bidjigal Reserve’ that includes an Aboriginal cave that was likely used regularly by Pemulwuy.

Nathan Dawson is a Gomeroi man from the Guyinbaraay clan from the Gunnedah area of NSW.

Nathan mainly uses water-colour, ink and pen.

Nathan has lived and worked in Japan for a total of ten years, during which time he was chosen for the NIKA Art and Design Awards for three years in a row and his works were exhibited at the National Art Centre, Tokyo.

Nathan presently lives in Lismore, NSW with his wife and 4 children.

Pemulwuy was a Bidjigal man born in 1750 at Botany Bay who later witnessed the arrival of Europeans in the 1770’s. Provided with special training as a young man in hunting, bushcraft, tracking, animals, cultural and spiritual knowledge, Pemulwuy had been marked by his elders for development.

Pemulwuy had the rare distinction of being able to travel anywhere in the greater Sydney region, including across boundaries of other Aboriginal tribes without being questioned or suffering any cultural reprisals.

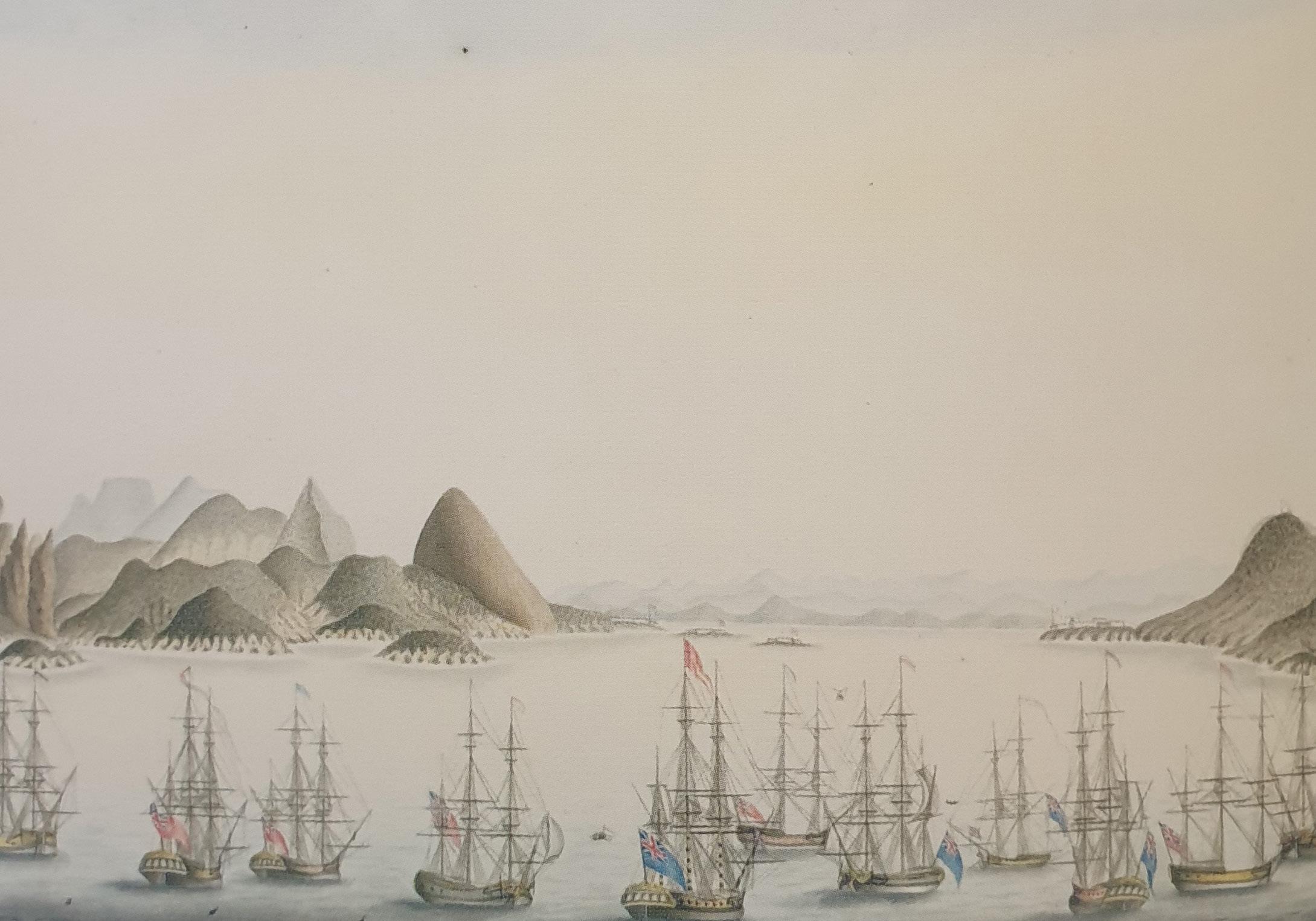

Pemulwuy was born in Botany Bay. Here’s Joseph Lycett’s impression of Botany Bay in 1824

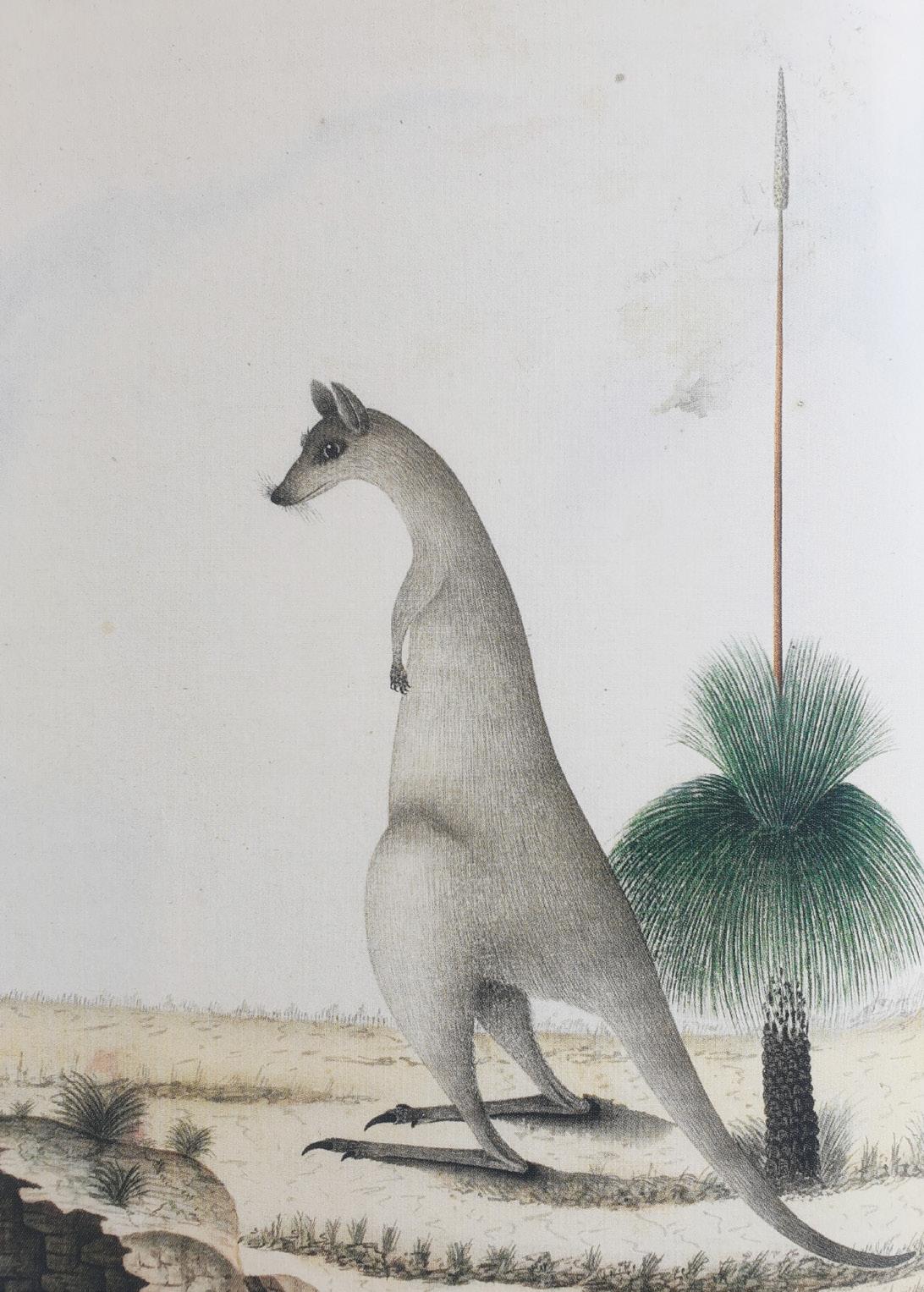

As you can see by the below watercolour and ink painting of a ‘kangaroo’ by the First-Fleet midshipman George Raper, the visitors were confused about the native fauna and their uses. Ironically, the grass tree depicted on the right by Raper in his artwork was the Aboriginal wood source for making spears to hunt kangaroos.

Pemulwuy, quickly picked up the English language of the colonists without formal training and in the early days, traded animals for western-made goods. This was particularly helpful to the new colony who were struggling with their own farming and food-making practices in the unfamiliar terrain that was Australia in the late 1700’s.

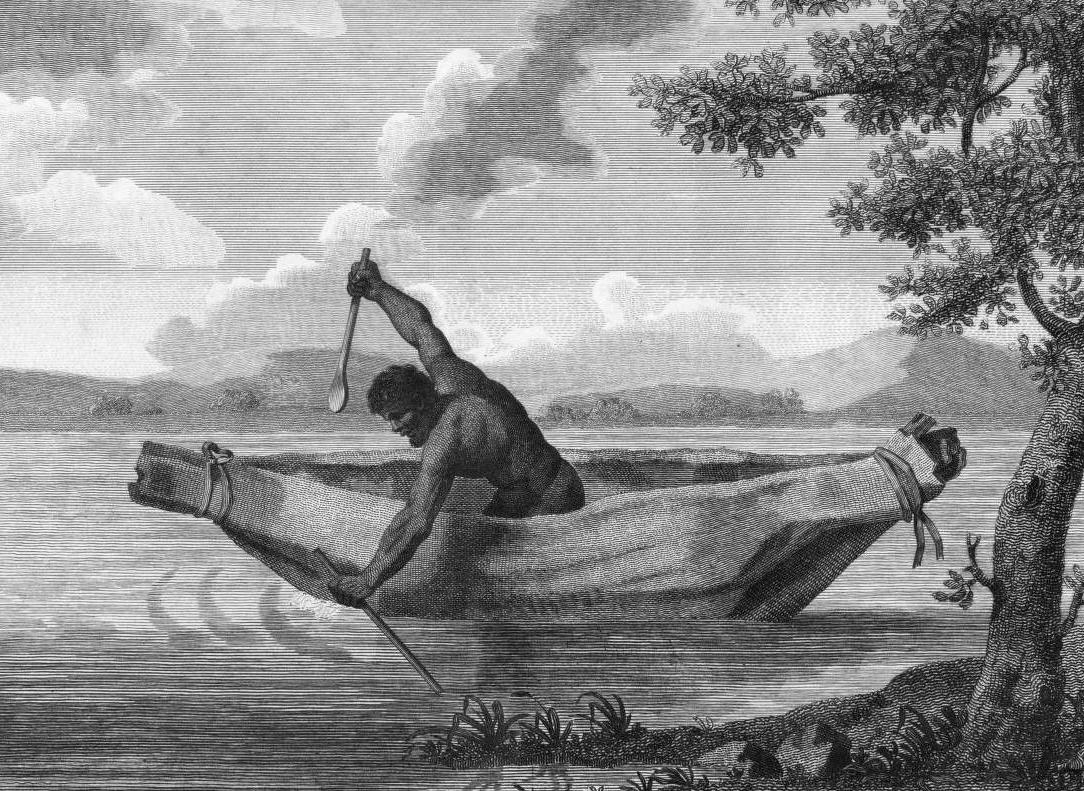

The image below is one of the only pictures we have of Pemulwuy that has come down to us through history. Here, Pemulwuy uses what looks like a large wooden serving spoon and staff to make his way along the water in a bark canoe. Being close to the shore, the wooden staff in his left hand could have been used to wedge into the river bottom whilst the inclusion of the serving spoon by the artist is more of a mystery?

Perhaps Pemulwuy was given the spoon as part payment for providing meat to the colony. Rather than using the spoon to make a campfire pot soup that would have made him an easy target. Pemulwuy, anxious to make use of his payment, could have enlisted some of these ‘curious implements’ in his fast moving style of travel across his Country.

The fact that Pemulwuy was willing to receive European goods in return for a supply of killed native animals suggests that he was an innovator and open to adding new ways of doing things to his deep cultural knowledge. It also suggests that there was a time in Pemulwuy’s life when he saw the Europeans less as enemies and more as colleagues, business associates and possibly even new friends.

Unfortunately, this happy relationship came to an end when Pemulwuy became increasingly appalled by the huge tracts of land being absorbed by the European pastoralists (that he was feeding) and the impact it was having on their traditional vegetables and food sources.

A number of Pemulwuy’s retributive raids and resistance struggles occurred in the Paramatta area for which he became very well-known amongst his peoples and the colonists. ‘Parramatta’ comes from the Aboriginal word Buramatta which means the place where the eels lie down and breed.

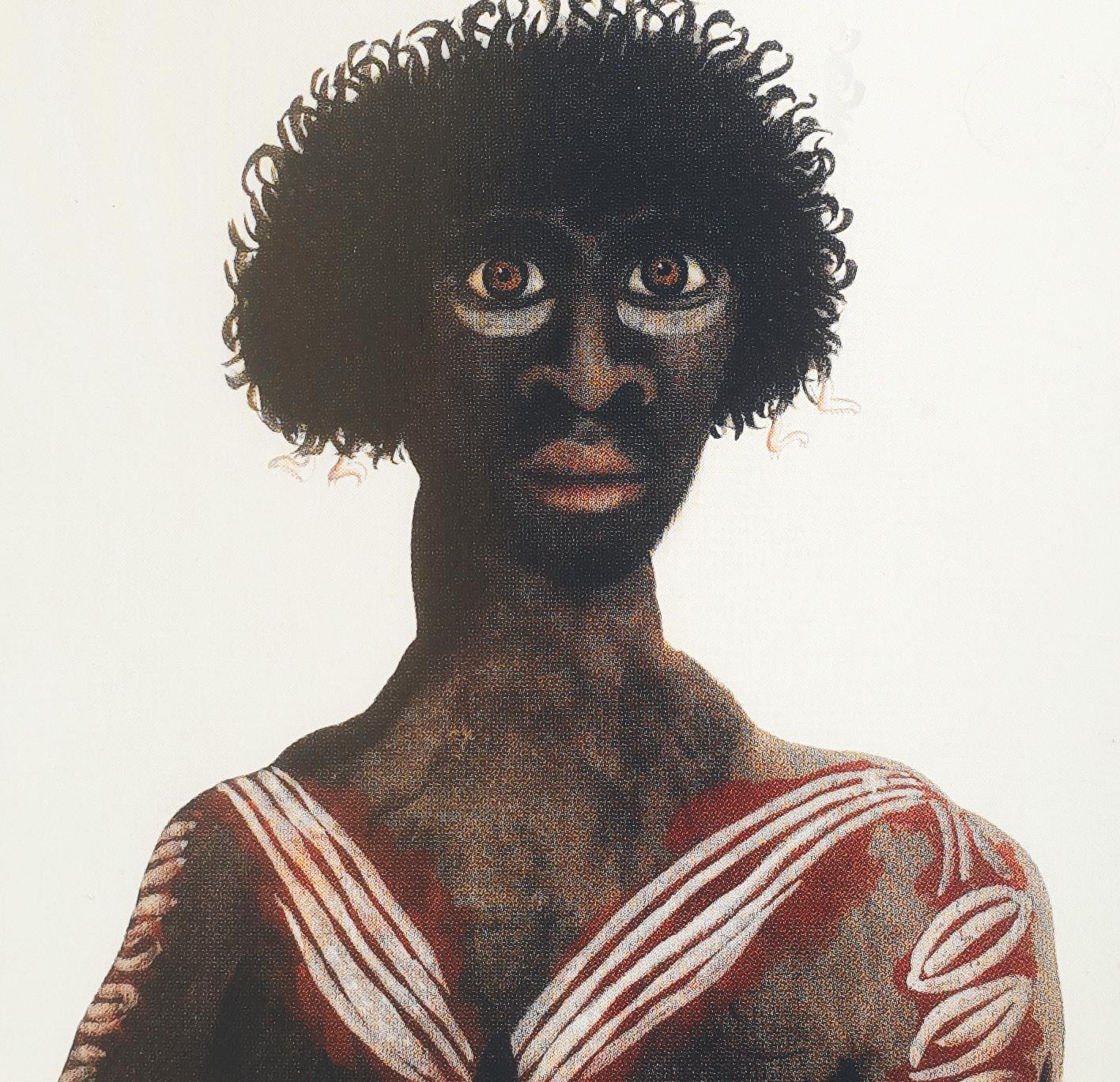

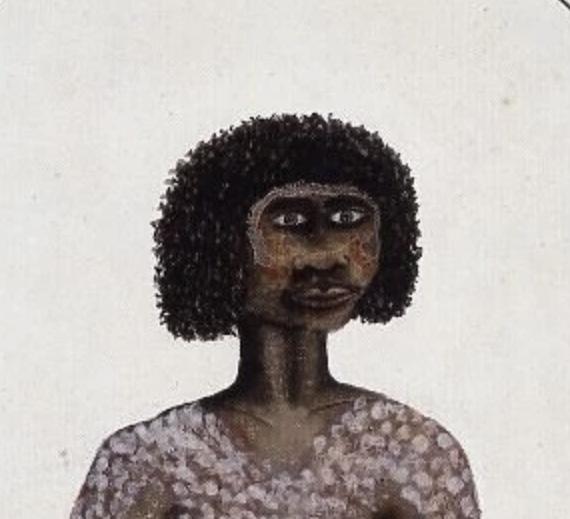

Bennelong, pictured below, was a person of interest to Pemulwuy that would have elicited mixed feelings from the warrior. When meeting with Pemulwuy and other Eora countrymen, Bennelong would wear traditional dress and observe the correct cultural cues. Conversely, when mixing with Governor Philip King, Bennelong would don colonial English dress and character. Such chameleonlike behaviour must have challenged Pemulwuy’s world view. However, Bennelong proved to be a convenient cross-cultural connector and negotiator for Pemulwuy whose rapidly diminishing patience with the Europeans did not allow for long, diplomatic exchanges.

In 1797, Pemulwuy led an attack against the Europeans at Toongabbie. After being shot, hospitalised and chained to his bed, Pemulwuy recovered and escaped leading to the development of a cultural view that he could not be killed by bullets and could turn himself into a crow and disappear.

A view that might have spread confusion amongst the colonial troops whom had been tasked to apprehend Pemulwuy. Whilst within the Aboriginal community, it may have been the culturally ‘right way’ to explain the relationship of a warrior, Pemulwuy, with his totem animal, the crow, including all of the spiritual and cultural interfaces that Aboriginal people believed possible.

Pemulwuy was also known as ‘Butu Wargun’ or the Crow (watercolour, Image FX)

The artist, Nathan Dawson, included the image of a crow carrying scales to symbolise how Pemulwuy was culturally authorised to carry out Aboriginal justice like a mobile courtroom, judge and if necessary, punisher of those who carried out violations of Aboriginal law.

In 2004, Cumberland Council created the suburb ‘Pemulwuy,’ that includes a ‘Butu Wargun Drive’.

In 2017 Transport NSW named one of their ferries ‘Pemulwuy’ to commemorate the life and times of this extraordinary Aboriginal man.

Maynard J (2014) True Light and Shade: An Aboriginal Perspective of Joseph Lycett’s Art

Mollie Gillen (1989) John McIntyre, The Founders of Australia: A Biographical Dictionary of the First Fleet (1989), p 231

Wilmot (1988) Pemulwuy: The Rainbow Warrior