HOLIDAYS BEGIN AT MACOMB

Party supplies

Special discount for advance orders

Known nationwide for quality selection of domestic and imported wine, beer & liquors

ếry few peoor but has now e unsspectingand with great insistence ént, etc.. That is to say, fala-la-ing across the grassy d spit it out of the mud with its and white petals fluttering about n completeabandon, the ink still moist on its leaves, and now i's asking you to snuffle up to it and get a hearty whif. Therefore, it is my responsibility to caution you, reckless reader, to exercize your sense of propriety and discretion in your perusal of this publication by following a

If, however, you choose to be swayed by that lascivious abandon which this sordid litle booklet so rampantly exherts, neither myself nor anyone connected with this issue of amlit is in any way responsible for either physical, mental, or emotional side effects

And that includes walking into trees, moving vehicles, hot dog vendors, etc., while blisfully prancing about with your nose snorting up

few general rules. which may occur. some poem or God knows what.

Let me be perfectly clear about this. The material before you, if ingested into your system raw, i.e., uncooked, unclean, as a slab of filthy old red muscular tissue, is most certainly toxic and possibly fatal. If prepared as according to specifications, however, it will prove to be a most delightful cocktail snack, or even a light dinner for two. The speifications are as

Remove the extraneous sheath of skin from the magazine's extenor,incluing the cover, pages, ink from the texts, etc., until you reach the entrails and the spine. Feed these to your dog. Take the edible section which you have dismantled from the rest of the whole and set aside. Boil two quarts of water with a tablespoon of oil to prevent the materials from sticking together, and add the magazine. Lower the heat to a steady simmer and continue in this manner for twenty two minutes until the remaining imagistic persuasions, onamatapoeic devices, and hythmic delusions have evaporated. To insure complete purity, simmer the water for fourty eight hours after this until it has completely disappeared. Look at the bottom of the pot and note the sticky membrane which has glued itself to the teflon. Scrape this off with a spatula and beat with two egg whites and a bit of salt, according to taste. It should have the odor and flavor of mayonaise. Spread the cooled mixture on a liverwurst sandwich with tomato and disregard any flatulation difficulties, as it probably has more to do with the liverwurst than the magazine. Belch. Enjoy.

The Staff

Editor-n-Chief

Julie Otten follows:

Poetry Editor

Mark Peters

Photography Editor

Derek McNally

Art and Photography Assistant

Betzy Reisinger

Boy Wonder

Russell Atwood

Editorial Artsy-Fartsies and Wise

Guys

Carl Hanni

Lara Heyman

Gregory Ticehurst

Rich O'Brien

Comic Relief

Adrian Marin

Jim ManzanoSpecial thanks to Linda Way and Madeline Coppola for their extra time in production, and to Kamel Abdallah for free publicity and relentless inquisition.

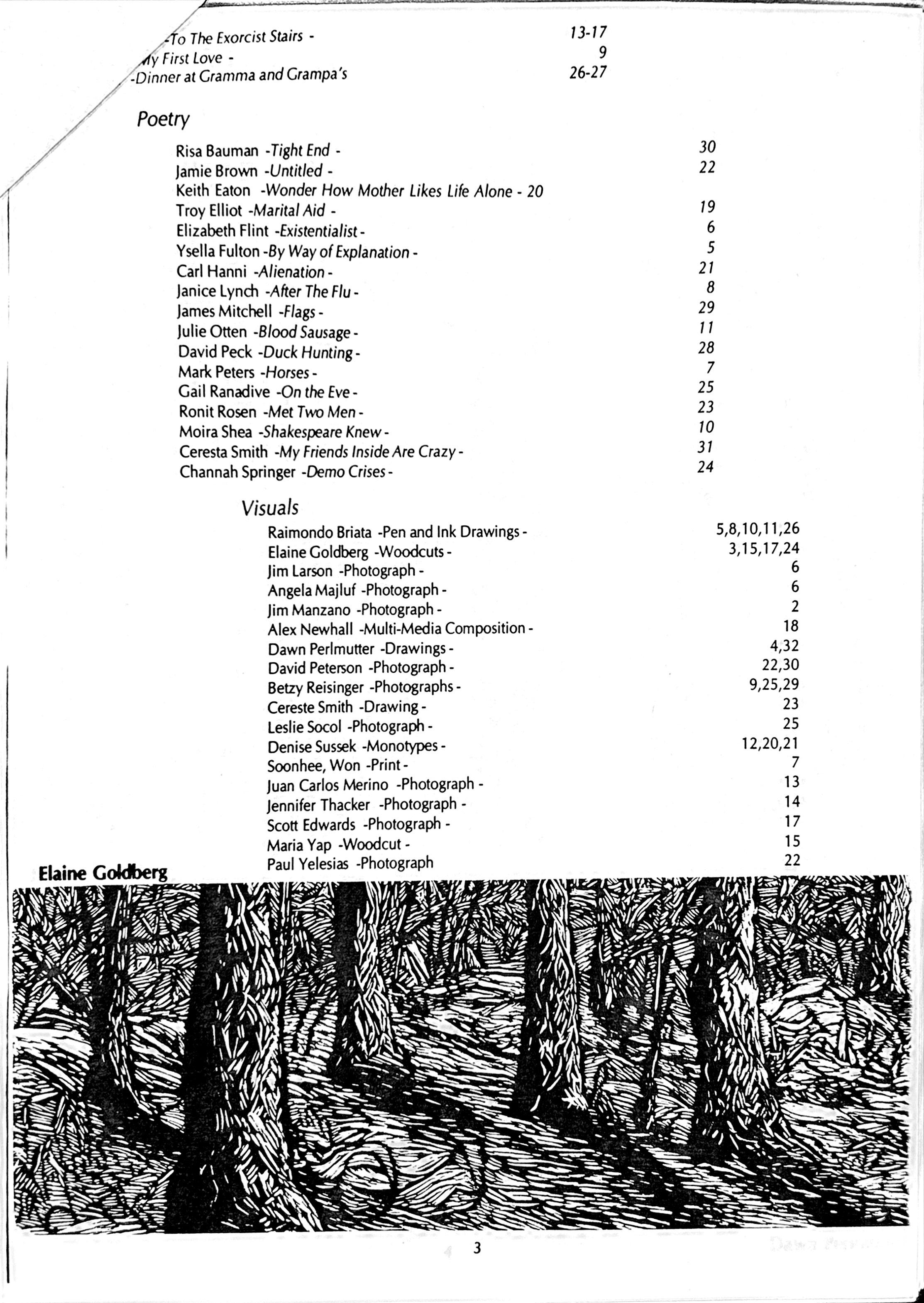

Jim ManzanoVisuals

WBy Way of Explanation

Socrates said that a poet had no idea what he was talking about, something just flowed into him through the crevices of his fingerprints through the small wrinkles of his eyes.

Do I then lose you in translation-when my words become flares on a quiet highway as I remember one of the last times I saw you. Boarding the plane I turned around.

Tell me how it isI know that the history of our lives continues like the parallels: those imaginary lines encircling the earth, moving in the same direction but separated always by the same distance.

I know a poet who thinks in metaphor. Who walks home on a busy street after weeks of snow and sees a map of our sins on the sidewalk. Rare

snow spattered with mud, stained with soot and hard as ice. When talking to you I yearn to push through phone holes to live arteries that connect us.

Who knows why constant images fill our hearts, crows descending upon dead trees or green grass secretly growing under snow. All | can see is ink discoloring fingers.

Existentialist

When I was young and all I knew of nothing was the moan of a late afternoon plane, I thought I could go on forever, playing in timeless woods, humming, trusting my attention to the small details of earth: a bird's nest, acorns buried in the soil, a flagging barbed-wire fence, darting salamanders. I have learned now by rote how we must construct a living life. Set goals and people to meet, decide on a couse, and yet cary in our weight the enormity of weightlessness.

Like the hummingbird we survive on our own busy movement. And if not, buildings and cars and people will fall away until only a silent burial ground remains, a desert of far-off places. And if you should look down hoping to find a lizard, you will catch only a human foot-print left like a fosil in cement. And only the slow obtuse clouds to understand, or care.

Jim Larson Elizabeth FlintSoonhce, Won

HOtses EDr Wnnates eyes

araloph hroughho ibaty o woui

that we chooe bltlosdonekod keepGreyhne n paca ttesoundo asas

Cnleaer

AEUght aogdorce andeaahd baween Wodes ptse

to teieeaof you ofceuhe loveofyoU to icelheoicioyou

ths miantgods

Mark Peers

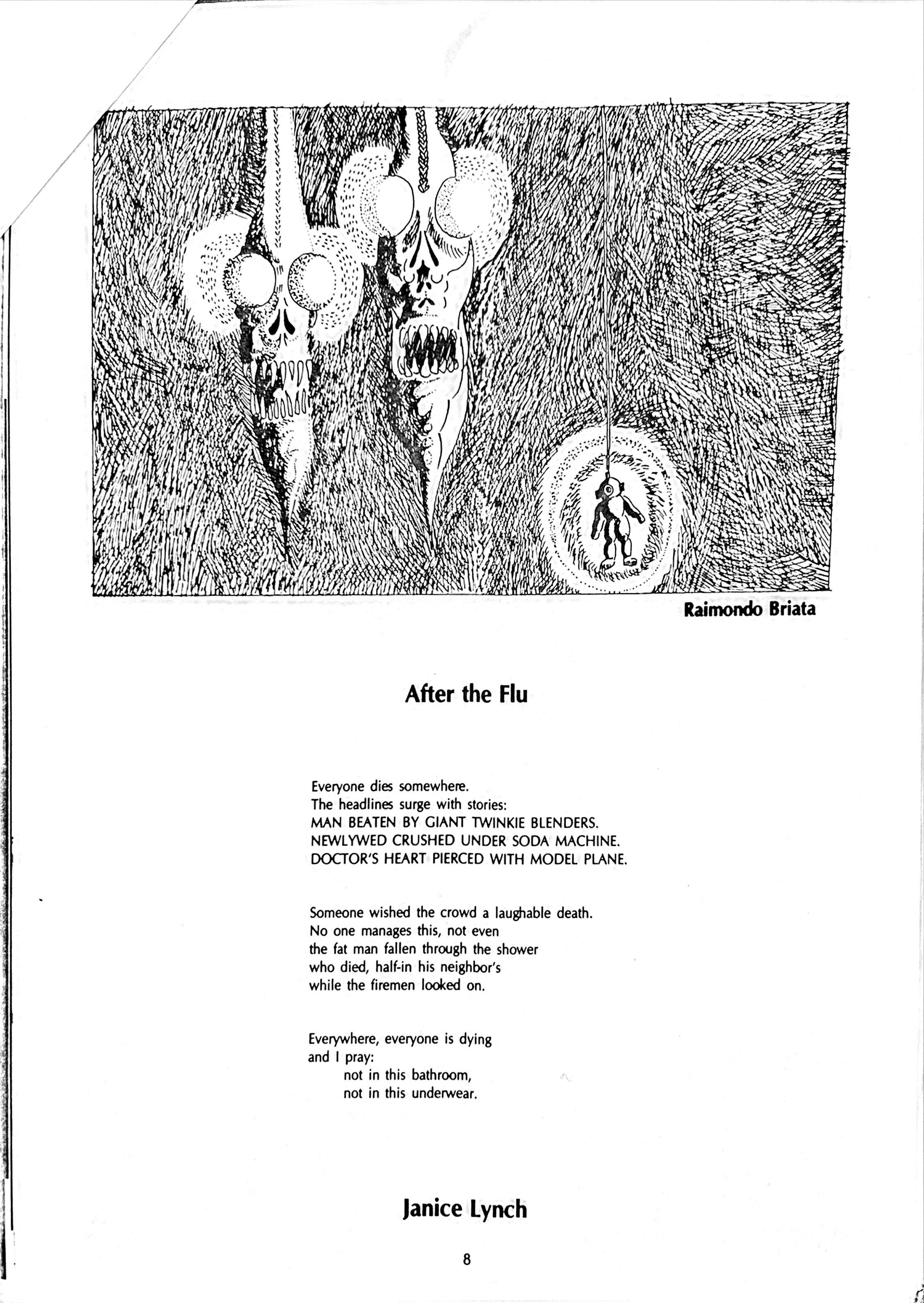

After the Flu

Everyone dies somewhere. The headlines surge with stories: MAN BEATEN BY GIANT TWINKIE BLENDERS. NEWLYWED CRUSHED UNDER SODA MACHINE. DOCTORS HEART PIERCED WITH MODEL PLANE.

Someone wished the crowd a laughable death. No one manages this, not even the fat man fallen through the shower who died, half-in his neighbor's while the firemen looked on.

Everywhere, everyone is dying and I pray: not in this bathroom, not in this underwear.

MY First love

ois owedasste ShonlálhervardsweweredaynaspendngeveryaternoonholGinghandsinliepank nbblinson exottfoodseandisenjovingeacholher company A(anynonhslarersheinoued nwhme Wesnarstruy darigien sbelhadatoS VRadsjoSanalie wasnesebale Untotunateyaherúndleloillshorthateahat, andhehad to pend nany nithtshssde BiShe laayscamabac and shelmetomaketg brcakastandikdserveher thbedAew

Ssdierhende sosckhetoldmeshgoddntnndlavoisthg orahl wasdong welat myieand coultk SUPporMljetywochS-Thi alowetiet o pen herday tesokunleand wheoshasohomeoteO20setomias

onUDsčayisyassotn themornng:Sheyasnot hom yet enoihung myselinthekrchen withanentensont cams tnendswnehanging all grebuetn the yellw Kchenancktughed.Sheawhe empybotleowhiskegand chilleckhth sweanng chatftererotank herbooz gain,shedtlB:Vene

She cunedowa ae, andládirnybodyonthe loor Shepred. oytrozen e apartandjumpedonmyabiom oytntGeeLWAmhghs onmysonachassheipped nyshitand an hersharpnal,acosthe tlis oonyetest sie sappedmy helesnesstothelying oomturniture.oncemoreand fo he firsttimewanted to tell herthatdidta ie Wanted toel herthatihalcelberand ha ve 1Rugno,pleasureinher pan.

hjghahahesyindowIseenow iured byteasandbladesAwbitelabcoattusheovelo ne a yeoiyon bedlhstaps me down, TcoemyeyesanexpectationwishingthatKcouckaeam, Shescoiogto harensttAn.

shakespeare Kne

In Troilus and Cressida

There are No heroes (Thersites could never qualify despite his big mouth) Achilles

Only wants PatrocluUS To nibble His nipples. And Hector wonders if she's really Worth it Watching her stuff the face That sank a thousand Bodies. The gods are truly Şilent forever Aere in The Age Of Reason.

Moira SheaBlood Sausage

No one invented the blood sausage.

Rain swarmed. Moss devoured wagons in yards.

One pig remained, potato, some flour.

Children ran rings around the storm. Leeches clung to clapboard. Ashes.

Two hands knead the gentle, hoary throat of the hog before a siphon.

Julie Otten

Julie Otten

siding with Mrs. Niilsford in amy argument. She doesn't necessarily mind going, the stairs are tucked away, out of sight. She's surprised Gross even knows about the spooky steps, certainly he's never seen the movie. His mother would never allow it and they always watch television together. But he would know about them, because they are spooky and so is he, at times breaking through her professional vest of indifference and shaking her up, like when his eyes constrict and his pupils shiver as if they're trying to squirt out information.

Five minutes later, 20% more cavity-fighting power in eight-outoften children tested blares at Zim's fortress and she slaps the clock-radio, twice, hard. She is No, she doesn't mind. Today she wants to keep close watch on Gross, on him just being himself, on what can happen, on what possible reason there might be for him.

up, over the line.

Whack! It all comes back to her, like the solid breath the drowning man takes after momentarily hallucinating air. The panic passes under the covers; in the dark, her ace aches as it assumes unusual expressions of despair.

Don't stop for a moment. Keep busy, the mind off

Despite last night's forecasts of showers, seven-thirty a.m. Tuesday morning is only partially cloudy with 40% chance of rain. IT.

Zim slaps her dock-radio into silence and drills down deep into the warmth of her blankets, calculates with large colorful numbers in her head the amount of time irll take her to get to work, drifts.

Her day is laid out for her and shell have to wear it Yesterday she'd given in and promised Gross that if it didn't rain, they'd go to "The Exorcist" stairs. She doesn't have to follow-through; she's cetain his mother would object, but Zim cannot picture herself

13

A relatively ordinary chain of events produced Grosvenor Niilsford. Two months into her pregnancy Mrs. Nilsford became ill, one thing after another, including an assault of pneumonia for four months. During her recovery, Mr. Niilsford was shot and killed interrupting a robbery at a self-seve gas station in Maryland. Mrs. Nilsford went into shock. A itle

over a month later, on December 27, she gave birth to her son prematurely.

Grosvenor is not aware this is a bad date for a birthday, that he gets gypped on presents. Being so close to Christmas, he can anticipate its coming: the trees glow with lights, the sun does not give heat, Rudolphe the Red-Nosed Reindeer is on TV. One day he'll just pronounce it, "Decemmer twenny-sevimí," out of the blue, and you know he's thinking about it in his own way.

Zim thinks about the three transfers she must take from Anacostia to where Mrs. Nilsford and Gross live. Still lying in bed, she uncovers herself and looks at her feet and at how ugly they are, nasty not-toes-butgerkins. A horrrible feature for genes to affx to a child. She showers, but there is nothing at this time in the morning she can do about her hair. It sticks up like black barbed wire. Not that Gross would care. He can't care responsibly. But he does. About the stairs at least. Something she couldn't care less about. They are different in many ways.

Gross is a whie, rich man. Zim is a black, comparatively poor woman. He is twenty-seven. She is nineteen. Gross cannot think in words. Zim can. Gross' physical handicap is visible. Zim's is not yet apparent to anyone but Zim (she knows, knew the very second, will know forever, feel this way forever, for as long as she's awake). Gross' spindly insect hands are cold when her hands are warm, and warm when her hands are cold. Lying flat, Gross is 68". Zim is 5'6".

Her mother is in the kitchen. Caught up in looking natural and unchanged, Zim does nothing out of the ordinary. Fluffy. golden, blueberry-specked pancakes go down Zim's throat like bits of slate. Nothing must show; she wolís down her breakfast as if she is hungry. Her mother talks to the stove, to Zim, yells out into the hallway that time is precious, washes a pan, never meets her daughter's eyes, hollers out into the hallway that five minutes have passed since she last hollered, and takes a deep breath.

"Peaches, it's a cold day, wear your heavy coat," she says looking out the window, her eyes fogged by grey light. The lines on her mother's face are dry cuts; they slice her features up into a jumble of shapes. The deepest lines make her mouth a frowning half-oval threatening to become dislodged.

Once in Zim's stomach, her breakfast sheds its disguise and swells into a coiled boa (if only this pain were her period coming on, but these wishes are beyond her now). She thanks her mother, kisses her neck, intensely watches her profile; emotions affect her face, revealing other faces, hostile, aggrieved, suspicious, silly, rarely placcid, never neutral. All through life, whenever she tells her mother a secret that hurts, Zim has tried to anticipate what face will be provoked. It is eardy but even her look of weariness is ferociously alive.

ming and Zim used to help get her sluggish bulk into her bathing suit. The suit was decorated with ripe stalks of corn ready for harvest and, in the side, had a small tear out of which would burst a bulb of DiDi's flesh. Zim used to feel bad about feeling good about her own body next to DiDi's, her own life next to DiDi's. She'd leave the hospital feeling lithe as a French model, delicate as a charcoal drawing, and go to Derek's, elated, and love him for being bright enough to know she was a good catch, the right one to be in his arms, tasting his ears.

The advantages of DiDi's life are dear to her now. DiDi has already paid her debt and is being taken care of

On the back of the seat in front of Zim is scrawled DEREK BKA QUIK-DRAW MCGRAW of S.E. His "D'" is a bloated half moon, his " an arched eyebrow over his leering "e." Derek has let his magic mark on every bus, traveling to places he doesn't particulariy want to go, just in order to autograph the transportation. He doesn't ownma car, but she loves him anyway.

On the ripped-open red vinyl seat beside her is printed: DENYS plus SHANE, SHANE plus DENYS 4ever. What woukd she write, in long elegant letters while the bus was stopped at lights, if she had a magic

marker?

ZIM plus DEREK

ZIM plus DEREK plus-NO!

ZIM plus PLUS equals ZIM minus DEREK

ZIM minus DEREK equals ZIM minus ZIM Minus ZIM plus PLUS-NO! Minus PLUS 4ever. "Goodbye, Mama.

At the hospital where Zim trained to become a medical technician (amounting to less than a nurse, more than a babysitter) and at the camp where she worked for the past two summers, most of the handicapped people were white awkward sons and daughters of those who could afford special care, who knew the right people to squeeze in order to sidestep waiting lists. There was one black girl, DiDi, at the hospital; her favorite thing to do was to run off from the rest and hide in the cafeteria, lying flat against the wide, level linoleum floor under a round table studded with spent chewing gum. DiDi also enjoyed swim-

The words in Grosvenor's mind are independent agents; floating free of syntax, he has no language. His pronouncements benefit no one, they lack motive; he voids in his pants poker-faced and cries soundlessly as it goes cold. Yet he voices observations: "grass" (when smelling his sperm-damp sheet after a wet dream), "chockylite" (when he met Zim for the first time), "wretna" (unexplained)

No way has been found to coax him into speaking., his bouts with language are as unheralded as inspiration, uttering three words in one day and then not a

Like many things about him, Zim is still mystified by how he picked up "Exorcist" and connected it with "Stairs" (a word he's always known). Grosvenor is a strange case.

"Grosvenor! l am going now," Mrs. Niisford blows from the dull marble foyer, her throat wiggling. a vexa-

tion to behold, "Zimmy is here."

Zim and Mrs. Niisford hear a rumble of a chair, a Scream across the linoleum, and in a couple of seconds, Grosvenor fights his way out of the kitchen.

"Be a saint today honey," Mrs. Nilsford says, adjusting a veil of yellow starfish mesh over her wide, pink face. She hands Zim a ten dollar bill folded three times and two dollars in quarters, "Here. Don't forget

Zim is having her doubts about where they are going. Did Gross actually say "Exorcist stairs" as she first assumed? No. Gross pronounced, "Eggs oh sis stirs," but what does that mean? At the ime they were at lunch in McDonakd's, maybe he just wanted an Egg MCMufin and a trawberry shake. Zim made her assumption based on Gross' past interest in stairs. it, for years before that he'd never been out of the house. He knows the crumbling, pebbly part, the two smooth white squares following it, the place where the sidewalk opens like a drawbridge over swelling tree roots, the mended section which retains fossils of fallen leaves, the slate tile path in front of the green fire hydrant, the sharp edge of the cub, and the gutter. Since Zim has been working with him, his scope has grown.

Wherever they walk and encourter ten steps or more, they must sidetrack and climb them before Gross will advance another inch. When descending to or ascending from the Metro, his choice is always the inactive escalator in the center. What vicarious thrill he gains is a mystery. His favorite places to visit because of this are monuments and museums; after the white marble climb, the interiors are anti-climactic for him.

Yes, it made sense then, which is why she doubts it now (Gross rarely makes sense). f she read a particular meaning into his sounds, then isn't it her own sound for two weeks. Clearly, he preters hearing to being heard.

They stand beside the bus stop. Gross grips the metal pole and the red-white andblue flag waves. desire that is leading them to the stais?

Rising from the road like bread the bus approaches, a Greek column on wheels.

Gross climbs-his hands going pale with tension, his knees battering the open double doors-onto the bus. Zim follows him and they walk to the middle of the bus as it grinds and bumps to the left, over the curbing, promptly seating Gross.

Where are we going? Zim has often asked herself in other circumstances. If she knew, she could prepare herself by making the right decisions As things stand right now, she believes life is nohing but chains in the making. She, her mother, her grandmothers, her great-grandmothers, are links to greater links, somewhere all onnected into an iron net. One, huge, sprung trap. She tries, but cannot suppress this feeling that she's a circle closing in on herself. She

wants to break this chain.

At Tenleytown, Gross and Zim exit the bus thru the back door. They wait at the intersection for the crosswalk signal to blink WALK" in bright white spots, "WALK."

"Come on, we can cross now," Zim says puling on the big guy's sleeve. He's as thin as a gnawed-on bone, but she can't budge him. his pill."

As the door closes, Zim and the big guy look at each other. His face is an uncluttered canvas; eyes high in his smooth forehead and set apart from a dwarfed nose. His jaws are bearded; wiry srands, tangled and

knotted, shadow his Adam's apple.

She can tell by the frenzied, crucified expression on his face that he has not forgotten.

You want to go see the Matisse exhibit?"

He stares. Stais.

Gross leans his head against the window and watches through a clear patch. He imagines he is actually outside the bus, in view of himself, able to speed dangerously parallel to the bus, not riding a motorcycle, but endowed with the same dynamics. His eyes dart and seek and find openings to skirt through; he jumps every obstacle (hedges, garbage cans, parked cars, a moving van, a telephone repair truck) but one, the side of an overpass tunnel. He crashes and disintegrates-darkness--only to reappear on the other side, unhurt miraculously. Sometimes his eyes roll and he rides the waves of the telephone wires, or close and he drops into a manhole, burrowing deep beneath the frost line.

"l said, come on."

His attention span is as wide s a silent river; his gaze is caught on a Xeroxed poster glued to the one tree on the block. It reads, The Batlecats in concert, appearing at the Black Crow Bar & Microwave Oven on November 14th, with WE-X-0." It is the picture which has caught him, a collage of unrelated magazine cut-outs: two gloved hands set apart as if they're holding a lounging head, framing a face contrived of two olives with tears dropping from them, a goat's nose, and a white and black golfshoe tongue. It looks like a crazy face, which explains his fascination

would be beautiful.

Zim leaves him stooped at the front door. She wanders through the houUse. If she owned this place it She'd have opal vases on pedestals, a cut-glss bowl on the ebony-finished coffee table, jade and marble statues you could sit in the corner with and run your fingers over for hours. The rooms lack fragile articles of grace. The upholstered chairs are hard as stone. The entire house resists liying. She circles all the rooms unil she's back in the foyer. Gross is waiting at the door, his jacket on

if not his empathy.

Zim reaches up and grabs hold of a splotch of bristly beard, tugs. His eyes shift and see her.

"We're crossing the street," she says. A soggy Cheerio comes off in her hand. "I bet I know what you had for breaktast

She wipes her hand on her white-uniform slacks, then loops her arm in his and steps off the curb as the sign starts blinking Halloween orange, "DONT inside out.

Rolling her eyes up and down, Zim says, "Ill go get WALK, DONT WALK," but they do. your boots."

Arm in arm, Gross and Zim leave the house. Her steps are shortened by the unpredictability of his long legs, and Zim takes time to notice the neighborhood so unlike her own. There is green grass, and trees, and blank walls, and the ground is clea, not covered by ribbons of broken beer botle or charred boards with rusted nails. This beautiful area seems desened. Zim would like to shou, "Here, over here," as if she has located an oasis and is calling out to those she wants to save. Ifany came running they would find what she

Gross is not the fastest walker in the world, his legs extend like squigsly lines, whipping haphazardly. Zim keeps hold of him, always walking on his right, his stronger side. She's been taking care of him so long that her left am is noticeably more muscular. Derek once pointed this out to her, as they lay exhausted in bed.

"Hell woman, that fruithead's makin' you lopsided. Ah, he's deformin' you," he said and sang low and twangy behind her ear like wam electricity, The freaks come out-tat nite, the freaks come out-tat..." cannot touch, a mirage.

The sidewalk in front of his house is Grosvenor's best know territory. For years he never passed beyond

Derek has never met Gross, so he is jealous of him, "A man is a man," he used to say, as if bodies would procreate without minds and Gross was just a loaded gun with a hair-trigger. As it tumed out, Derek was

month, three weeks, ány minutes ago, Derek olew her period away.

Ament in the basement of his ded on four layers of sleeping ying the sameside ofa Jimmy Cliff dagain. They were taking their time. han an hour into it, he exploded off her as a blanketedgrenade.

kost" he sad, dribbəling and shooting lvory dish oing liquid in two directions, "lust in time," he

This world she accuses the people and cars in Georgetown geting in and out of each other's way, what kind of world is this to live in, let alone populate? Ang, too happily to reassure her.

Zim knew that very second, long before she bought and used the e.p.t kit, but said nothing. She constructed her front and suffers alone.

Zim and Gross are in the middle of the road when the light tums green and cars start coming. Zim keeps walking. Someone beeps his hom. Zim settles a gun powder black stare on a silver luury mobile with diplomatic plates, a tan hand extended over a tinted

window, waving to shoo them. Zim stops. handicapped. So fuck you."

"Hey man. You think we're on a date! This man is

While everyone else on the sidewalk is mimicking the flow of traffic in the street-staying on the right side, passing on the left-Gross uses the whole sidewalk, really occupying his space, and people get out of his path, jumping into doorways, hugging NO PARKING signs, colliding with newspaper dispensers.

blouse, cummerbund) smiles with traight, white-out teeth and seems not to miss his absent lower torso.

A man waits posed on the comer beside a cutch.

Six TV sets display the same picture the Cookie Monster-with six different hues; he is blue, he is grey, he is aquamarine, he is green, he is purple, he is

Finally, Zim and Gross make it acoss and a number dissolving into a spectrum of snow.

30 bus stops and opens its doors to them.

The bus driver has black, glistening, curly hair and too much rouge accenting the high heek bones of her dark brown face. She smiles at Zim and says, good moming, and Zim thinks she's beautiul even if her

Zim and Gross take a seat up front.

Someone has let behind a Washington Post, folded and tucked down between the seat cushion and the wall. Zim pulls it out and read, Tuesday, November 11, 1986, FINAL. She fips through looking for news about South Afia, but either reports have been choked back or yesterday was calm. The way she's been feeling today, she's afraid something dreadtul is happening there right now, a mutilation, one death, two deaths, a bombing: and she can do nohing about it but tomomow read about it or witness tehnicolor seconds this evening on TV. Her breakfast leaps

halfway up her throat and she can taste acid.

She reads an article about a pill that can induce a miscarriage and may one day replace abortions. It will be available in the U.S.A. in two yeas. Zim can't wait

that long. She's been sentenced.

Zim's options are limited.

The average person's options are 1) go to a dinic and get rid of IT, 2) get married and have T, 3) have, keep, and raise IT alone, 4) give IT to someone who wants IT, and 5) don't make up your mind at all.

Zim has been oasting along on the last option and knows it must end. The others seem impossible to her because so many things coukd go wrong, and she is woking on an option of her own. She knows sudden, rough, physical movement can cause a miscariage. She drops the newspaper on the floor and a color ad supplement spreads open between her feet and covers a wide area. Meat on sale.

The bus driver hums and dee dee da's a melody Zim has never heard, and then sings softly, "if eyyYye could just touch the hem of his garment I know eyyyYye l be made whole ight now." Zim coses her eyes and gratefully lets the woman's voice become her thoughts, filling memory, fear, desire, all the parts of her mind.

Someone else pulls the stop-request cord for Georgetown, "Ding-ding."

"Back of. People coming down," the driver says as Gross propels himsef forward, "Easy now." Zim thanks her.

The woman holds Zim's eyes within her gaze, says, "Cod bless you, child," and embarrasses Zim.

What a thing to say, Zim thinks, latching onto Gross and pointing him in the right diredion. Zim believes in God and believes He is a Fool. She can understand how everyone alive before her could love and respect Him, but feels time has finally revealed Him to be a Poor Planner and only human.

It is funny that Gross and Derek have never met because looking at him now, Zim detects a similarity: the way Gross walks is the way Derek dances; out of control, Derek becomes a meter of the music, registering eratic chord changes and percusion solos like some kind of seisnograph. She'll miss dancing with Derek when she's.lumpy, when-say it, say IT, what's the use-when the baby begins to grow in her like a fattening leech, living in her, off her, until one day it'll live outside of her, off her. She'll never go anywhere, see anything, be anyone ever. She can't

Businesses die off as they approach the area of the stairs. The closest store, Dixie Liquor, is two blocks away; its parking area has a sign that reads: THOU

SHALT BE TOWED. front teeth do tum in on each other.

stand having this inside of her. No more, no how.

M street atacks Grosvenor's senses. He smells French fries splatering, then urine off a jumbo pile of clothes sleeping open-mouthed in a doorway. In one window an alligator is surrounded by slick, bejewelled cowboy boots, in the next a young man fastened in black leather, a scrub-brush of platinum hair on his head, eats a bagel. Neon lines sizzle. Beyond a dark doorway a banjo struts its song side by side with a bass drum's bonk. A pale pink female with isosceles triangle breasts, turquoise underwea accenting each sharp edge, stares glumly without blinking from a wide window. A man in formal attire (bow tie, frilled

Zim is a litle disappointed. She should've realized the stairs would look nothing like they did in the movie. Though they appear only briefly at the end of the film as the possessed priest tumbles down them, she left the theater, after the images had passed, with a strong sense of how the steps looked: black, brooding. slick with drizzle like motor oil, and 90 degrees straight up; only good for quick descents. The movie was poweful in this way. She recalls how people were terrified, but at the same time joyful, as if the film's establishment of the devil was irrefutable proof of God's existence. But as Zim kept telling herself during it, scrunched up in her seat, hand over her eyes, "I's only a movie, it's only a movie

Camera angles had something to do with it, but also the steps have seen better days. Set back from the road, past a boardedup gas station, the steps are as wide as an alley and situated between a black granite wall on the left and a red brick building on the right both seventy-five feet high. A shet metal chute, blemished with ust, runs down the side of the brick building juts out above and before the steps and ends hovering over a long rectangular dumpster filled with broken-up pine crates. The top of the granite wall is lined by a black wrought-iron fence embedded in sparkling grey granite. The grey granite reaches out and connects the wall and the red brick building by an

arch high above the botom steps.

The edges of the stone steps are wom and blunted and not razor sharp as she'd hoped.

While she is disheartened, Gross is elated. His eyes bulge as he focuses on a circle of blue sky at the head of the steps, and trembling, he raises his foot and slaps his palm on the ool, paint-chipped handrail. Gross ascends with much dificulty. His foot slips now and then and he often loses and finds his balance. Usually when Gross climbs stairs Zim follows behind and spots him. Today she has other concems and races up the steps past him. Twenty-five steps and she comes to the first landing, twenty-four steps and she comes to the second. On the charred wall to her left someone has painted BLACKOUT in white. Twenty-four more steps and she is a the top looking down at Gross on teps number eight and ten. It is not nearty as steep s she imagined. The priest woukd never have fallen the full length in real life; he would have tumbled down the top twenty-four steps and stopped on the landing, bruised, a lite broken, but

still hopelessly possessed.

The sidewalk at the top is cluttered by crinkly brown leaves, soda bottes, and potato chip bags.

The granite wall leads up to the badk of someone's yard. The iron fence runs all around it keeping people out of a shub garden. The fence is a row of identical black spears; each point looks like a black star rising from a pursed blad rose bud.

She looks down at Gross approaching the first landing, and then out over the granite arch at the Potomac swelling in the distance She follows the arch to the brick wall, then back to the iron fence. At the base of the fence is a ledge. Zim teps up onto it. Grasping the points of the spears, moving hand over

hand, shuffing her feet, she heads for the arch.

At first there is only a short drop beneath her to the steps below, but the next time she looks she's above Gross on the second landing. She moves farther out.

When she gets to the omer of the fence where it tums and traverses the steep granite dif, the freedom of empty air shodks her. She can feel the steady

revolving of the earth.

The traffic inching its way acros the Key Bridge twitches like a serpent. The buikngs beyond are

She shakes her head and hums, "Hmm-mmmmhmm," as her grandmother would on a shadowed and sleety day. The sky has darkened. She sits up, leans back and grabs hold of the fence. She stands and faces Gross. He looks stupid as usual.

"Hmph. My saviour."

Zim inches her way towards him.

Gross' eyes roll back and forth in his head as if he's trailing a spastic gnat. He seems to have goten the impression that this was the way they were going and now he's lost. He tries to move in reverse, but his heel catches in the fence.

hazy and seem made of clouds and fog, not stone. The ground is a spoiled child begging her to come to "No Grossl! Stay"

His arms row back free in the soft open air and he drops out of sight. it now. She mus take this all in frst.

She lets go with one hand, then lets go with the other and drops to her knees on the granite arch. The top is specked with bird shit, the stone is rounded and smooth and her legs slide and she is straddling the

"Grow"

Gross' body, twice, as carefully s she can without moving him. No limbs are broken. His ribs are intact. A hundred things she can't detect and he can't tell her about could be wrong with him though, so she bolts

away to call an ambulance.

The pay phone at the boarded-up gas station has no receiver.

She wishes to say a few words to her mother at this time, explaining she's no longer her litle Peaches, apologizing, comforting, absolving. She was always horrified by the prospect of her parents dying and

Gross' right shoulder hits the thirty-ninth step and all the air escapes from his body. He somersaults soundlessly down, leg foremost, head foremost, butt foremost, he puts up no resistance. His light frame jumps the first landing and slides down the remaining steps like a log riding the rapids.

She tums back to the stairs and gasps.

Gross is on his feet mounting step after step. arch, balancing her weight.

"Gross!" she yells, running to him, "Gross, are you okay?"

No response. At least the fall hasn't knocked any sense into him. There is a red scape on his cheek below his right eye, but otherwise no visible injuries. leaving her alone, now this pain wl be averted. She can't think of the fall. She concentrates only on the sensation of rolling over in bed and going back to She walks behind him up the stairs.

sleep. Such a simple thing.

"HeiyuuuUwwwuummmmmm Gross hollers working his way towards her along the narrow ledge.

"Gross! Co back."

He is ten feet above the steps. Then eleven.

Zim's mind is clear glinting stainless steel. Somehow she makes it down the steps to him without breaking her neck. She crouches and says his name, "Grosvenor, Grosvenor." Her eyes are hot like roasting chestnuts and she bends to the ground and puts his stone cold knuckles to her eyelids.

"Oh now I've done it. Oh God. I've done it now. Oh, Grosvenor. I just thought... elt. tried." She can't remember the words that brought her to this point.

"Stop. God damn you. This is my business. This is His hand opens and closes.

"Gross?" my say-so. Stopl"

Gross doesn't stop. He moves without any of the

care Zim took, yet he advances.

"Shit," Zim says. What's he doing? Does he want to join her? Does he know? Zim can see the sensational headlines now, PG WOMAN KILLS SELF AND DISABLED CHARGE.

l am stupidstupidstupidstupidstupidstupidstupid.

Zim steps back, takes off her coat and slides it under his head. Starting with his right foot, she unlaces his boot and begins to examine him; with both hands she feels his ankle, moving slowly up to his shin, knee, thigh and pelvis. Beginning back at his left foot she repeats her touching search. She feels every part of

A cool speck touches her nose, then her cheek. She touches the sky. It is raining. By the time they reach the top, it is pouing. She huddles close to Gross for shelter, he leans over her. When she tums and looks back, the steps are just like they were in the movie, as ink black and resilient as the flesh of killer whales. She cannot capture her breath for an instant, as if she's facing into a tomado, and shoves Gross on, starts him moving down the sidewalk towards Prospecd

Street, his loose boots clomping.

Russell Atwood

Hints From Heloise

1. Catch it asleep on the sofa after Christmas dinner, mouth open, spit stains on the pillow. Take a picture. Next year the family will laugh at the picture, how life could sleep through anything, how the dog's eyes glowed while your life drifted off.

2. Buy very expensive liquor. Get your life drunk in hopes that it will say something profound or sad. Wait patiently with pen and paper until it throws up on your shoes. Clean carefully with vinegar and warm water.

3. Have the kids make a video for your life. Be sure to include spikes and smoke and dancing girls. Make your life go on talk shows and mouth the words to songs. Have your life die a sudden, violent, tragic death. Sell t-shirts.

4 Stick a bicycle wheel in your life and call it art. Call it theory. Call it art as theory of art. Submit papers about your life for publication in journals. Invent a word for your life and become famous for that word.

5. Use your life as a planter, an earring holder, a lamp, a festive wall hanging. Over the weekend, make your life into a hutch, a coffee table, bunk beds for the kid's room. Cover your life with woodgrain vinyl and nail bronze baby shoes to the top.

6. Sprinkle your life on fish, poultry, or beef. Make a quiche with it that your family will find disgusting. Stuff it down the garbaage disposal. Listen to the grinding, how it has a tone that gets clearer and clearer as your life passes through. Memorize that tone, make it your theme song.

Troy ElliotWonder How Mother Likes Life Alone

When it rained for three days in Canada, we played fifty hands of Gin. During the last four years I've heard your voice over the phone on Sundays, you speak of gardens and the trees. At home I see you crouched in the dirt plucking rocks from the ground. Black flies don't seem to bother you.

Father returns on weekends to find fresh air and vegtables. He enjoys dirt in his salad. He's growing accustomed to your earthy flavors. My friends relax with your quick jokes and a beer. One Christmas you urinated blood for seven days, not telling a soul until your parents left. They had a wonderful time.

Carl Hanni

Carl Hanni

David Peterson

David Peterson

Cereste Smith

Cereste Smith

David Peterson

David Peterson

ALT-0-

ALT-0-