6 minute read

How Did I Find My Way Here?

Dr Tanya Davies

Rural Queensland

Advertisement

1985 Melbourne

Started Medical School and graduated in 1991 (including a gap year with 4 months in Ghana, Western Africa)

Rural Victoria Darwin

Whew! It sounds exhausting looking at it, but it was a wonderful journey of growth and learning (both in medicine and my personal life). Was it what I had planned? No. But I don’t think you can plan for the sort of work I wanted to do.

Rural Victoria (again!)

Adelaide

Finished GP training in 1998

My medical journey started when I was 15 and read a book called ‘The Ugly American’ by Lederer and Burdick. It talked about all the aid projects that different governments and aid organisations ran in a small, fictitious Third World country during the Cold War.

Remote Northern Territory Locums

Utopia Community, Central Australia

2000 - 2002

2002 Wau in Sudan with MSF

Numbulwar Community

Needless to say, it referenced all sorts of different types of approaches — from big, government-level programs (both Western and Communist ones), to the different, idealistic approaches adopted by smaller aid organisations. I decided that I wanted to do this as a doctor (a GP, specifically), so that I know my patients when they are well as well as when they are sick. And, that I would do this in Africa.

Eastern Arnhem Land 2006 - 2012 Darwin

Doing systems, policy and advocacy 1 year trip to the UK doing both clinical work and management/systems.

2012 - current: Katherine, Northern Territory

I worked hard to get into medicine, which I did in 1985. I had to leave my home in the USA and come to Australia (where my mother was from). I knew what I wanted to do with my life — study medicine, and then move to Africa and ‘save the world’. During my journey, particularly in medical school, there were constant expectations placed on me. There was pressure from the establishment to follow the well-trodden paths to general practice or further specialisation. Luckily, each time I started to listen to others, I would meet someone who had done something ‘different’ and done some Third World work. It wasn’t long till I would be re-inspired to get back ‘on track’ with my life.

However, life saw fit to throw me a curveball every now and again.

Generally, I describe my journey like being on one side of a big lake. Entering medicine, I could go anywhere I wanted on that lake. For me, I aimed where I wanted to go, jumped in a motor boat, and then put the throttle on ‘fast’!

But, then life came and hit me from the side — WHAM — with the suicide death of my father. I tumbled out of the boat. When I got back in, I did the same thing. Very fast, in a direct line to where I wanted to go. WHAM — life hit me again, this time with the suicide death of a very close friend. Again, I tumbled out.

I did that more than twice. It took me a while to learn my lesson. But, eventually, I changed to rowing a boat with oars. I still had some control through the ‘oars’, but the row-boat allowed me to move with the wind and the tides. Eventually, at a more gradual clip, I reached a place that was both very similar and very different to what I had initially planned.

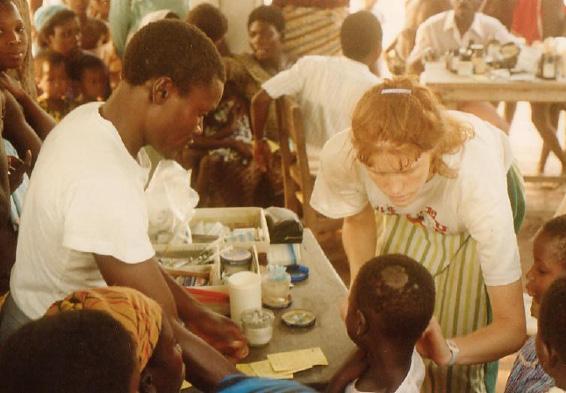

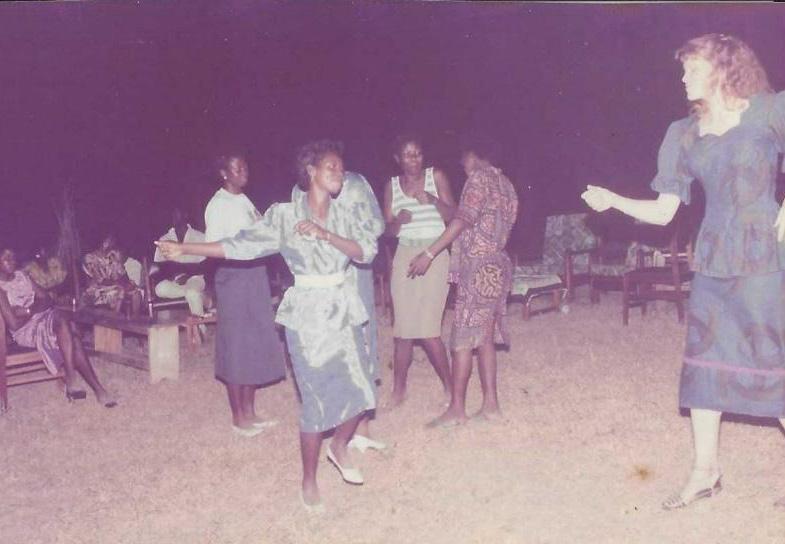

Along the way, I had the most amazing experiences. In Ghana, I experienced the wonderful people and culture of Western Africa. I was living in a rural town (Donkorkrom). We would go on trips to help remote villages accessible only by boat, situated within the huge Lake Volta on the Afram plains. I learnt local dance techniques — the exhibition of these techniques often being met with a loud cacophony of local laughter (all in good fun!). In Ghana, I also met a range of different clinicians and representatives of aid organisations, all with very different approaches. One would build on local strengths, improving handdug wells in remote villages. Another would follow organisational rules and use Western farming techniques to cultivate crops. This was despite the completely different context, land and plant make-up. I certainly could see the parallels with ‘The Ugly American’ book and the different aid approaches.

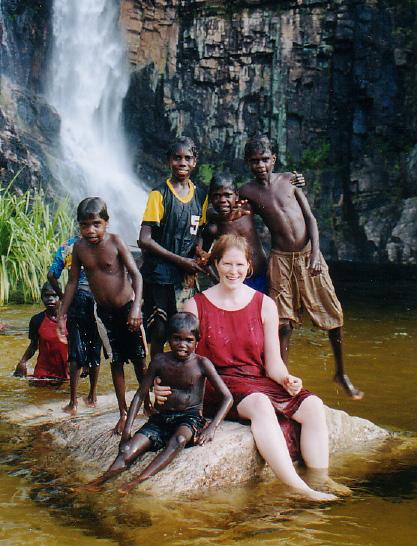

In a remote NT community, I was adopted into a local family. Here, I learnt of the complicated expectations inherent to community relationships. Being involved in circumcision ceremonies as the doctor, as well as being allowed to sit and observe other ceremonies, was a huge honour. It was confronting though, to see the range of illness and disease suffered by our very wise

and proud First Nations people. This included adult-onset diabetes in young people, and severe eye injuries (requiring me to remember the rules for caring for penetrating eye injuries while flying). I also saw meningitis in a small baby and pulled a cockroach out of an ear (yuck — my most hated procedure!). This was all while being immersed in a culture that is more than 40,000 years old, and trying hard to adopt to modern customs.

In Wau, Sudan, I worked with some of the most amazing people. The local staff were suffering as much as the community they were serving, but had to endure through famine, massacre and other painful challenges. Seeing how they responded to a measles outbreak was impressive. We couldn’t do anything without the local people, who are always the unsung heroes of international humanitarian aid.

AMSANT is the Northern Territory’s peak body for ‘Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services’ (which are run by Aboriginal boards). Here, I learnt a lot about the strength of the Aboriginal community and their elders. It is critical to listen to their voices when trying to work out what the issues are, what they want to address, and what the possible solutions are. We (mainstream white society and politicians) try too hard to identify ‘the problems’ and ‘the solutions’ without listening to local groups. The issues and solutions are very different for different groups of people.

Where Am I Now? My Take-Home Messages

Currently, I am the Medical Director of an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service in Katherine, up in the Northern Territory. We provide health services to 3500 people over 75,000 square kilometres (the size of Tasmania) with 9 community clinics, 4 GPs, 30 Remote Area Nurses, 8 Aboriginal Health Practitioners, a range of Allied Health professionals and other clinical and nonclinical staff.

Is this where I was aiming for, when I was standing at the edge of the lake?

Actually, YES! - I have been involved in delivering healthcare in many underprivileged areas, both in good times and bad (which was my aim). But I’ve not spent the last 20 years in a developing country. Instead, the Aboriginal people in remote NT communities, particularly in the Sunrise region, have become my people. Hopefully, the work I do will aid them in taking over their own care. If I could work myself out of a job (that is to say, be followed by an Aboriginal doctor), my work would be complete. » Keep your eyes and ears open for opportunities — you never know what doors will open when you seize a new opportunity. » Pause long enough to notice those open doors! » Take a chance — have confidence in yourself! We have excellent training here in Australia, and you have the skills! » Don’t forget TEAMWORK. Your teammates are your greatest assets. » Humility — the doctor is not always the most experienced person in the room.

Your teammates have amazing things to teach you about the care of the patient.

You are just one cog in the wheel. » Most of all – ENJOY the journey!