28 minute read

Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding menstruation

Advertisement

Parinda Shah Sapna Dilgir Torres Woolley Ajay Rane

BACKGROUND

Various taboos and myths exist in different cultures surrounding menses and these have contributed to lifestyle restrictions and induced preventable stresses for many women. Several studies have highlighted that it is important we promote education, so future doctors have a holistic understanding of this topic and are able to provide destigmatising care. There is currently minimal literature describing medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding menstruation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS A cross-sectional questionnaire study was conducted to explore the current knowledge, attitudes, and practices surrounding menstruation among final year medical students at James Cook University (JCU). Quantitative analysis was applied to closed questions, and open-coded questions were thematically grouped.

RESULTS The overall findings (n=65; response rate=35%) highlight that while misconceptions on menstruation exist in Australian society, university is a vital source of menstrual health knowledge. Approximately half of the students felt that studying medicine normalised menstruation, while the rest felt there was no change in their attitudes as they were comfortable with this topic prior to medical school. Studying medicine also contributed to changes in 20% of female students’ menstrual practices.

The forms of social stigma identified by students were grouped into 4 themes (n=24): (1) religious and lifestyle restrictions, (2) stigma stemming from males in society, (3) the use of degrading language when referring to menstruation, and (4) unwillingness to discuss the topic. There were also varying views towards the use of medical interventions for the cessation of periods.

Recommendations from students for improvements to the JCU medical curriculum included providing more information on (1) different cultural perceptions of menstruation, (2) practical elements linked with menstruation, and (3) medical knowledge relating to menstruation and menstrual health conditions.

CONCLUSION Studying medicine is reported by medical students to improve knowledge, promote positive attitudes, and enforce hygienic practices regarding menstruation. This, in turn, can help reduce misconceptions and promote menstrual hygiene in the wider community. Menstrual health and menstrual hygiene are evolving concepts in the developed world. Unfortunately, various negative misconceptions exist in different cultures surrounding menses. The resulting shame and social stigma have contributed to lifestyle restrictions and high levels of psychosocial distress for many women.[1-8]

Research has been conducted in high income countries outlining the impact of menstrual disorders, such as endometriosis, dysmenorrhoea, and heavy menstrual bleeding, on women. These conditions impact all areas of a woman’s life—social, physical, emotional, sexual, and occupational—preventing them from carrying out activities of daily living.[3,9,10] Despite this large burden of disease, there are minimal studies assessing the knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding menstruation in high income societies. Like many Western countries, disparities surrounding menstruation are also present in Australia—mainly amongst Indigenous communities, low socio-economic backgrounds, and rural communities.[4] Globally, a lack of knowledge is a major barrier to menstrual health management as it can lead to misconceptions, negative cultural and social norms, and negative menstrual experiences. [7,8,11] Several studies have highlighted that we must promote menstrual health education, especially amongst adolescents and healthcare providers, to prevent these outcomes.[1,2,5,12-15] Currently menstrual health represents a low priority in health education amongst remote regions of Australia.[4]

Medical practitioners, particularly female practitioners, are in an ideal position to promote menstrual health as they are menstruators themselves, allowing them to empathise with the difficulties faced by menstruating women while administrating care to their patients. Hence, doctors, as influencers of menstrual health amongst females, must be both knowledgeable and comfortable with the subject so they can provide compassionate and destigmatising care. Incorrect practices, inaccurate knowledge, and negative attitudes amongst those implementing menstrual health interventions, such as healthcare professionals, can interfere with patients receiving correct information.[5,7,15] Therefore, it is important to assess doctors’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding menstruation. This, in turn, can improve education at a medical student level,[13] to ensure a solid platform is provided from which future doctors can effectively manage menstrual disorders, reinforce correct menstrual practices, and

One of the suggested ways to improve menstrual health management is to increase research on menstruation.[4,5,11] However, there is limited literature exploring medical students’ knowledge about menstruation. The few studies that exist are conducted in Asia and Africa,[2,17,18] with no studies focused on menstrual knowledge, attitudes, and practices in high-income countries. Hence, this study aims to

1.

2. Explore the current knowledge, attitudes, and practices surrounding menstruation among final year medical students at an Australian university. Identify any educational gaps in the university’s medical program regarding this topic.

METHODOLOGY

James Cook University (JCU) Human Ethics approval (H7473) and a letter of support from the College of Medicine and Dentistry at JCU were obtained prior to commencing this low-risk study.

SURVEY

A cross-sectional survey was developed in collaboration with 4 subject matter experts (i.e., specialist obstetricians and gynaecologists). This consisted of open- and close-ended questions covering five main areas: demographics, knowledge, attitudes, practices, and potential improvements to the JCU Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) curriculum. For the full survey, please see Appendix A (available at https://www.ajgh.amsa.org.au).

PARTICIPANTS AND DATA COLLECTION

The survey (Appendix A), with an attached information sheet and consent form, was distributed via e-mail to all final year students enrolled in JCU’s MBBS program in 2019. The survey was voluntary and anonymous.

The participants’ demographics in terms of age and gender were representative of the 2019 JCU medicine cohort, according to data obtained from the JCU medicine administration department.

A brief medical curriculum review was conducted to understand the topics taught in the current JCU MBBS curriculum. This was completed by liaising with relevant lecturers involved in teaching this topic throughout the 6-year degree. The responses were downloaded into SPSS 23 for Windows (International Business Machine, Australia). The data was coded into dummy variables and analysed using frequencies and Chi square tests. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Thematic analysis was carried out on student responses to the open-ended questions, which involved manually coding the data into common themes.

RESULTS

Out of the 185 students enrolled in the final year of the university’s MBBS degree in 2019, 65 students (35%) completed the survey.

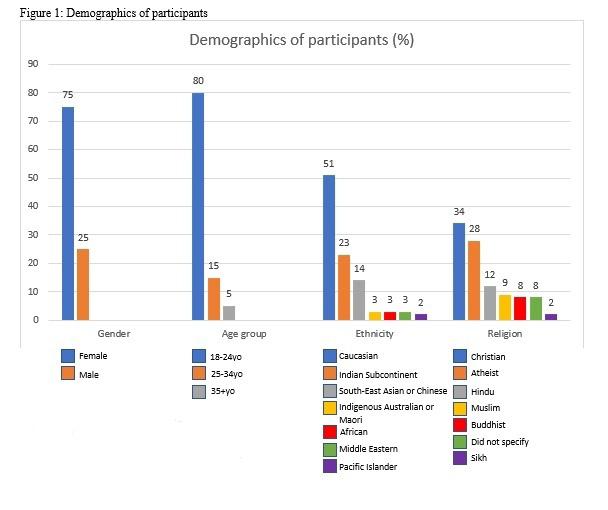

DEMOGRAPHICS OF PARTICIPANTS

The demographics of the 65 students that participated in this study are outlined in Figure 1. Overall, majority of students were female (75%) and 18-25 years old (80%). This was somewhat reflective of the 2019 medical cohort at JCU which has more females (61%) and students aged 18-25 years (68%). In terms of ethnicity, Caucasians constituted a small majority (51%) of respondents. With regards to religion, majority of respondents were Christian (34%), followed by atheists (28%).

KNOWLEDGE

The main three sources of knowledge about menstruation were university (57%), followed by family (45%), and school (35%). Friends (25%), Internet/media (25%), books (3%), and health professionals (2%) were other sources of knowledge. Most male students obtained their menstrual knowledge from university, whilst female students obtained their knowledge not only from university but also family and school (Table 1). Caucasian students were more likely, and Asian students less likely, to have family as a source of menstrual knowledge (Table 2a and 2b). This was supported by student quotes such as ‘[Sri Lankan] grandparents refusing to talk about [menstruation] openly’.

The MCQ-based knowledge quiz consisted of questions related to the menstrual cycle, dysmenorrhoea, toxic shock syndrome, and heavy menstrual bleeding. Most students outlined the role of progesterone in the menstrual cycle (72%), defined secondary dysmenorrhea (77%), identified the cause of toxic shock syndrome (74%), and outlined the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding (89%). A score of 100% (4/4) was obtained by only 39% of students despite being final

Overall, 82% of students agreed studying medicine significantly improved their understanding of menstruation.

ATTITUDES

The main factors influencing attitudes towards menstruation were knowledge (95%), demographics (54%), and opinions of family, friends, and colleagues (46%). Most students stated knowledge influenced their attitude towards menstruation, with students reporting they were now more empathetic towards menstruating women and increased knowledge had built open mindedness regarding the topic. Other factors influencing attitudes were culture and religion (42%), media (29%), and personal experience (2%).

Students were asked to identify forms of social stigma regarding menstruation, and their answers could be grouped into 4 reoccurring themes. The first theme was religious or lifestyle restrictions, such as not being able to enter places of worship, being unable to sit on furniture, or not being able to attend a funeral due to cultural beliefs. The other themes included stigma stemming from males in society, the use of de-grading language when referring to menstruation, and unwillingness to discuss the topic.

The latter theme was common, with 19% of students, both males and females, stating they felt uncomfortable talking about menstruation with their peers. The main notion was summarised by a student who stated discussing menstruation is like ‘discussing defecation/urination’. Additionally, female students felt uncomfortable when discussing the topic with male peers. There was no correlation between feeling uncomfortable and age, gender, ethnicity, or religion, though this may be due to the small sample size available to test these relationships. Furthermore, 22% of female students felt they were treated differently at least 50% of the time whilst menstruating. Two students from those who participated specifically mentioned that social stigma, either through dismissive attitudes or religious associations between menstruation and impurity, was a barrier to women acquiring medical treatment for menstrual health issues.

Regarding the impact of studying medicine on students’ menstrual attitudes, 46% of students felt medicine had normalised menstruation. Fifty-four percent of students stated there was no change in their attitude, as they had previously been open or indifferent to the topic (Table 3). Five students also noted that studying medicine had highlighted the stigma towards menstruation in today’s society. One student 17 said, ‘for a very common/natural occurrence for females, I was surprised about how taboo the topic is’. When asked if they felt comfortable conducting a consultation and managing patients from various cultural backgrounds who present with menstrual health issues, 89% of students felt comfortable. The remaining felt uncomfortable, as they were unfamiliar with different cultural and religious differences surrounding menstruation or would have difficulty in discussing the topic with paediatric patients.

Attitudes towards using medical interventions for menstrual control, such as intra-uterine devices, the oral contraceptive pill, or other forms of contraception, were varied as evident through their responses to the open-ended question. Majority (69%) of students stated that cessation of periods should be a patient’s choice, that this gave them control over their body, or that it can reduce the inconvenience menstruation poses. All students aged 25-34 years largely held this view (p=0.022). A student clearly outlined the impact of studying medicine on changing her views on this topic, ‘I have seen women become functionally impacted by dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding that requires medical intervention to enable them to function in society. Prior to this I believed we should all be menstruating’. Interestingly, 42% of students believed menstruation should only be ceased for a medical indication such as dysmenorrhoea, anaemia, or disruption of a patient’s quality of life. Forty-six percent of students aged 18-24 years (p=0.043) and 59% of Christian students (p=0.037) held this notion. Lastly, 14% of students viewed menstruation to be a natural process that should not be ceased.

PRACTICES

Sixteen percent of female students currently followed cultural or religious restrictions while menstruating, including not entering religious places or being isolated in separate rooms whilst visiting their home country. Asian students were more likely, and Caucasian students less likely, to follow such restrictions (Table 2a and 2b). Of the female students, 45% felt menstrual symptoms significantly impacted their lives. For instance, menstruation resulted in taking time off from educational duties or work commitments and even interfered with relationships. Furthermore, 43% of female students found sanitary products posed a significant expense.

When asked if medicine had contributed to a change in their menstrual practices, 20% of female students stated that it had instilled some changes. These included changing their choice of sanitary products

from tampons to menstrual cups, increasing their frequency of changing the products, or commencing contraception to obtain menstrual control. The reasons for these changes are outlined in Table 4. Male students were asked if they were aware of specific menstrual practices. Most (81%) male students mentioned practices related to sanitary products, such as type of product, frequency of change, and risk of overflow. They also mentioned the need for analgesia and cultural or religion-enforced practices, such as the use of menstrual huts or not being able to enter religious areas while menstruating. As outlined in Table 5, when asked if studying medicine had impacted how they treat women who are menstruating, 75% of male students stated there was no change, with the remaining 25% stating they were now more empathetic towards menstruating women.

IMPROVEMENTS TO THE JCU MBBS PROGRAM

The curriculum review outlined the menstruation-related topics taught in each year level of MBBS at JCU and the methods used to teach the topics (Table 6). Overall, 37% of students believed the JCU MBBS could be improved. Recommendations for improvements could be grouped into 3 themes: more information on different cultural perceptions of menstruation, more information on practical elements linked with menstruation, and more medical knowledge relating to menstruation and menstrual health conditions (Table 7).

DISCUSSION

This study highlights the knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding menstruation among Australian final year medical students, and it is the first of this kind in a high-income nation. Students reported that studying medicine positively influenced their knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding menstruation.

MEDICAL EDUCATION: A NECESSITY AND ITS IMPACT

Our study demonstrates that medical students have varying sources of information regarding menstruation, reflecting the variety in their cultural and social backgrounds. For female students, as supported by the current literature, school and family members (especially mothers) are a key source of menstrual information.[5,15] Our findings that university is more likely to be the main source of knowledge for males is not surprising given boys would receive minimal education about menstruation at school, and they would not necessarily require discussions on the topic with family members.[2] Interestingly, Caucasian students were more likely to state family members as a source of knowledge than Asian students. This could be explained by the fact that the same degree of openness in discussion of such matters might not exist in some Asian cultures.[1,2,19] These findings clearly demonstrate the importance of teaching menstruation to university students, especially as males and students from Asian backgrounds may not receive this knowledge during their younger years.

Our study highlights that the current curriculum may be effective in levelling students’ understanding of menstruation, despite pre-university knowledge and influences on menstruation, as there were no gender, age, or cultural-based discrepancies on knowledge performance in this study. In medicine, where all doctors will be responsible for managing menstrual-related health issues, it is important that physicians have a solid platform of knowledge on the topic, despite their demographic factors. Gaps amongst certain demographics of doctors, such as those highlighted in a study where male paediatricians had significantly lower knowledge than their female colleagues for certain menstruation-related topics, can be a barrier to adolescents receiving medical care for an important component of female health.[15] In our study, a quarter of male students expressed they were more empathetic and had a greater appreciation for the difficulties faced by women during menstruation due to their medical education. Despite this, students felt the curriculum could be improved by incorporating practical elements for male students, including types of sanitary products, how to utilise them, and how often they should be changed.

A POSSIBLE GAP IN THE CURRICULUM

The current literature shows that, globally, a lack of knowledge is a major barrier to menstrual health management, as it can lead to misconceptions, negative cultural and social norms, and negative menstrual experiences.[7,8,11] An inability to discuss menstruation in an informed and comfortable way may interfere with identifying abnormal menstrual patterns, comprehensively evaluating patient health, and impact female preparedness for menarche.[15]

Given students in our study were final year medical students, it was surprising that 23% of students had a score ≤50% on the MCQ-based knowledge quiz. The questions that were most answered incorrectly were regarding the role of progesterone in the menstrual cycle and the causative organism

of toxic shock syndrome. This may indicate a gap in knowledge regarding normal menstrual physiology and pathophysiology of menstrual conditions that is not being addressed sufficiently in the university curriculum.

Menstrual cycle physiology and the pathophysiology of menstrual health conditions is taught in detail in Year 1 of the JCU MBBS degree and re-visited briefly in Years 4 and 5. It is possible that students performed at a level below that expected for final year medical students due to the vast volume of content they are expected to know at the completion of their degree, making it difficult to remember specific details on this subject. Retaining this information could be helped by teaching younger students, explaining the information to volunteer patients via role-play, or greater interaction with patient’s presenting with menstrual health issues during the General Practice and Obstetrics and Gynaecology rotations in Year 5.

MEDICAL CURRICULUM VS. MENSTRUAL STIGMA

Our study revealed that medical students were aware of social stigma regarding menstruation, such as religious or lifestyle restrictions, stigma stemming from males in society, the use of de-grading language when referring to menstruation, and unwillingness to discuss the topic. Some medical students admitted to being affected or influenced by this social stigma themselves. Specifically, some female students felt they were treated differently whilst menstruating, currently practised cultural restrictions, or felt their menstrual symptoms were not recognised as legitimate medical conditions. There is evidence that due to social stigma and taboos, women may feel embarrassed, ashamed, afraid, or may not be able to identify abnormal menstruation, hindering their ability to seek medical care.[4-6,8,20] This notion was also recognised by students in our study.

In the past decade, involvement of international activists, non-governmental organisations, UN organisations, and researchers have contributed to major developments in menstrual health, paving the way for huge social movements on this topic.[5-7] To support this movement and improve menstrual health management, medical schools need to promote awareness and education, eliminate stereotypical views of women surrounding menses, and outline the impact of sociocultural factors on patients.[2,7,12,17] Our study demonstrates that JCU’s MBBS program was effective in reducing stigma by encouraging open-mindedness and addressing misconceptions regarding this topic. This was evident from the 46% of students who stated studying medicine had normalised menstruation and made them more comfortable with discussing the topic. The remaining students felt they were already 19 open-minded about the topic. It is thought better understanding and openness on this subject is naturally created as both genders are taught simultaneously with a scientific approach.[2]

MEDICAL STUDENTS’ VIEWS AND PRACTICES – THE IMPACT ON THEIR FUTURE PATIENTS

Medical students hold varying views regarding menstruation and related topics. One such topic is that of menstrual control using medical interventions. Our findings that over two thirds of students, including all students aged 25-34 years, felt menstrual cessation using contraception was a patient’s choice suggests older students recognise the importance of menstrual control in a world where more women are studying and working. Furthermore, studying medicine exposes students to the difficulties of menstruation through their interaction with patients, highlighting the need for menstrual control. In our study, 14% of students felt menstruation should not be ceased as it is natural. This was significantly lower than Szucs et al. (2017), where 69-75% of female health science students considered monthly menstruation necessary for their health.[18] Underlying cultural factors in the differing settings of these studies may explain the differences in results.

Furthermore, 43% of female students in our study found menstrual products to be a considerable expense. Studies conducted in America and the UK also demonstrated that women were unable to afford the required menstrual hygiene supplies, resulting in use of unhygienic products.[16,20] Despite living in high income countries, these women faced some of the same menstrual challenges as women living in low-resource countries. A significant development in improving access to menstrual health products has been the removal of the tampon tax in many countries, with Australia leading the way.[11] A suggestion to improve the current medical curriculum mentioned that the topic of new reusable feminine hygiene products should be included. This would allow students to be more empathetic to the practical and financial challenges of menstruating and enable them to provide cost-effective options to their future patients.

Practices and beliefs of health practitioners may influence how they deliver patient care. Although there are no studies assessing this in regard to menstrual health, studies have been conducted in other medical fields such as palliative care and general practice which demonstrate that ethnicity and religion, as well as personal health behaviours impact provision of care to patients.

[21,22] Hence, a wide awareness of various cultural and social views regarding menstruation, as well as hygienic menstrual practices, are vital in providing open-minded and safe care to patients. This is particularly important as patients will have different needs and cultural beliefs in a multicultural society such as Australia. The JCU medical curriculum exposes students to different perspectives on menstruation during the first year of the degree. Although 89% of students stated they felt comfortable managing patients from various cultural backgrounds who present with menstrual health issues, students felt the curriculum could be improved by exploring perspectives by listening to menstrual experiences of women from different cultural backgrounds and role playing.

LIMITATIONS

The results were limited by 2 main factors. Firstly, only 35% of the JCU MBBS cohort participated in the survey, lending to an increased risk of bias in the data. Whilst the participant demographics represented that of the overall cohort in terms of age and gender, greater participation in the survey may have resulted in a wider variety of views on the topic. Secondly, the study was only conducted at one university and only on a single year level; hence, the results cannot be generalised to all medical students in Australia.

IMPLICATIONS OF THIS STUDY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Overall, this study suggests that certain demographic and sociocultural factors influence students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding menstruation. Conducting comparative studies in other Australian medical schools, as well as other countries, would provide a deeper understanding of factors which influence this and allow for the development of more relevant and culturally appropriate medical curricula. More studies on this subject will raise awareness on the social stigma towards menstruation that exists in the Western world and encourage research into strategies to overcome negative attitudes regarding women’s reproductive concerns.

Parinda Shah studied at James Cook University and is currently an intern at Blacktown Hospital, NSW. She is passionate about women and children’s health, in particular addressing the inequity between developing and developed countries.

Dr Sapna Dilgir is an obstetrician and gynaecologist who has completed a fellowship in pelvic floor and advanced laparoscopic surgery. She is a previous adjunct lecturer at James Cook University and is currently involved in teaching medical students at Griffith Base University. Dr Torres Woolley is an evaluation coordinator involved in evaluating graduate outcomes and curriculum learning activities across the undergraduate programs of Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmacy at James Cook University. He has over 20 years’ experience in research and evaluation methods, analyses, and software for both quantitative and qualitative methods, with a strong focus on the use of complexity-aware techniques in impact evaluations.

Professor Ajay Rane is a world renowned urogynaecologist who has acquired an Order of Australia for his aid work in helping women with pelvic floor dysfunction in developing countries including India, Bangladesh, Papua New Guinea, and Fiji. He remains passionate about education of medical students and is the director of the obstetrics and gynaecology training program at James Cook University.

Correspondence

parinda.shah@my.jcu.edu.au

Acknowledgements

None

Conflicts of Interest

None declared

References

1. Chothe V, Khubchandani J, Seabert D, Asalkar M, Rakshe S et al. Students’ perceptions and doubts about menstruation in developing countries: a case study from India. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(3):319-326. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pubmed/24618623. Accessed August 2019 2. Chang Y, Hayter M, Lin M. Pubescent male students’ attitudes towards menstruation in Taiwan: implications for reproductive health education and school nursing practice. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(3-4):513-521. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/pubmed/21457380. Accessed August 2019 3. Schoep M, Nieboer T, Van Der Zanden M, Braat D, Nap A (2019). The impact of menstrual symptoms on everyday life: a survey among 42,879 women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(6):569. https:// www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(19)30427-2/abstract. Accessed July 2020. 4. Krusz, E, Hall N, Barrington D, Creamer S, Anders W et al. Menstrual health and hygiene among Indigenous Australian girls and women: barriers and opportunities. BMC Women’s Health. 2019;19(1):146. https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-019-0846-7#citeas. Accessed July 2020. 5. UNICEF, Poirier P ed. Guidance on Menstrual Health and Hygiene. New York, USA: Program Division/WASH;2019. https://www.unicef.org/wash/ files/UNICEF-Guidance-menstrual-health-hygiene-2019.pdf. Accessed July 2020. 6. Simavi. The Global Menstrual Health and Hygiene Collective statement. Simavi. https://

simavi.org /quick-read/the -global-menstrual-health-and-hygiene-collective-statement/. Published March 2020. Accessed July 2020. 7. Tellier S, Hyttel M. Menstrual Health Management in East and Southern Africa: a Review Paper. UNFPA. https://esaro.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/ pub-pdf/UNFPA%20Review%20Menstrual%20 Health%20Management%20Final%2004%20 June%202018.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed July 2020. 8. Hennegan J, Shannon A, Rubli J, Schwab K, Melendez-Torres. Women’s and girls’ experiences of menstruation in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. PLoS medicine. 2019;16(5): e1002803. https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002803. Accessed July 2020. 9. Young K, Fisher J, Kirkman M. Women’s experiences of endometriosis: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2015;41(3): 225-234. https:// pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25183531/.Accessed July 2020. 10. Garside R., Britten N, Stein K. The experience of heavy menstrual bleeding: a systematic review and meta‐ethnography of qualitative studies. J Adv Nurs. 2008;63(6): 550-562. https://pubmed. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18808575/. Accessed July 2020. 11. Tull K. Period poverty impact on the economic empowerment of women. Gov.Uk. www. gov.uk/dfid-research-outputs/period-poverty-impact-on-the-economic-empowerment-of-women. Published Jan 2019. Accessed July 2020. 12. Atif K, Naqvi S, Naqvi S, Ehsan K, Niazi S et al. Reproductive health issues in Pakistan; do myths take precedence over medical evidence? J Pak Med Assoc. 2017;67(8):1232-1237. Available from: https:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28839310. Accessed August 2019 13. Garg R, Goyal S, Gupta S. India moves towards menstrual hygiene: subsidized sanitary napkins for rural adolescent girls – Issues and challenges. Matern Child Health J. 2012; 16(4):767- 774. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pubmed/21505773. Accessed August 2019 14. Upashe S, Tekelab T, Mekonnen J. Assessment of knowledge and practice of menstrual hygiene among high school girls in Western Ethiopia. BMC Women’s Health. 2015; 15(84). Available from: https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-015-0245-7#citeas. Accessed August 2019 15. Singer M, Sood N, Rapoport E, Gim H, Adesman A et al. Pediatricians’ knowledge, attitudes and practices surrounding menstruation and feminine products. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2020;20190179. https://www.degruyter.com/view/journals/ijamh/ ahead-of-print/article-10.1515-ijamh-2019-0179/article-10.1515-ijamh-2019-0179.xml?language=en. Accessed July 2020. 16. Kuhlmann A, Bergquist E, Danjoint D, Wall L. Unmet menstrual hygiene needs among low-income women. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(2):238-244. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/30633137/. Accessed July 2020. 17. Wong W, Li M, Chan W, Choi Y, Fong CA et al. A cross-sectional study of the beliefs and attitudes towards menstruation of Chinese undergraduate males and females in Hong Kong. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(23-24):3320-7. Available from: https:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24580786. Accessed August 2019 18. Szucs M, Bito T, Csikos C, Parducz Szollosi A, Furau C et al. Knowledge and attitudes of female university students on menstrual cycle and contraception. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;37(2):210- 214. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/pubmed/27923286. Accessed August 2019 19. Chote V, Khubohandani J, Seabert D, Asalkar M, Rakshe S et al. Students’ Perceptions and Doubts about menstruation in developing countries: A case study from India. Health Promot Pract. 2014; 15(3):319-26. Available from: https:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24618653. Accessed August 2019 20. Plan International UK. Plan international UK’s research on period poverty and stigma. Plan UK. https://plan-uk.org/media-centre/ plan-international-uks-research-on-period-poverty-and-stigma. Published Dec 2017. Accessed July 2020. 21. British Medical Journal. Doctor’ religious beliefs strongly influence end-of-life decisions, study finds. Science Daily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/08/100825191656.htm. Published Aug 2010. Accessed July 2020. 22. Oberg E, Frank E. Physicians’ health practices strongly influence patient health practices. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2009;39(4):290-291. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC3058599/. Accessed July 2020.

Table 1: Bivariate relationships between gender and participants’ main source of menstrual knowledge.

Variable – Main source of Female knowledge n (%) University 22 (45%) Family 28 (57%) School 21 (43%) *Calculated using 2-sided Chi-square Test Male n (%) 15 (94%) 1 (6%) 2 (13%) p-value*

0.001 <0.001 0.027

Table 2a: Bivariable relationships between Caucasian ethnicity and participants’ main source of menstrual knowledge and the current practice of menstrual restrictions amongst female participants.

Variable Caucasian n (%) Family as main source 20 (61%) of menstrual knowledge Female students 1 (7%) currently practising cultural or religious restrictions *Calculated using 2-sided Chi-square Test

Non-Caucasian n (%) 8 (26%)

7 (39%)

0.005

0.032

p-value*

*Note: Due to the limited number of participants, students who identified as from the Indian subcontinent, South-East Asian, or Chinese were grouped into the umbrella term of ‘Asians’ for ethnicity.

Variable Asian n (%) Family as main source of 6 (25%) menstrual knowledge Female students currently 6 (43%) practising cultural or religious menstrual restrictions *Calculated using 2-sided Chi-square Test Non-Asian n (%) 22 (55%)

2 (11%)

0.019

0.032

p-value*

Table 3: Selected student responses to ‘How has studying Medicine changed your attitudes towards menstruation?’. n (%) 30 (46%) Examples ‘I understand it better now and am able to make more informed decisions about my own health, as well as feel more confident to explain and give advice to others.’

35 (54%) ‘I’m by far more comfortable with discussing and understanding the female reproductive cycle now than before starting medicine.’

Why menstrual practices changed after studying medicine Female student quotes ‘Common myths were put to rest, i.e., I now know that it is safe to skip through sugar pills in order to not have a period.’

Table 5: Selected male student responses to ‘Has studying Medicine impacted how you treat females when they are on their periods?’.

Theme No impact, still treat women the same

n (%) 12 (75%)

More empathetic towards women 4 (25%) Examples ‘Whether or not a woman is on her period has no bearing on her ability to interact or function. Studying medicine has not changed this understanding for me.’

MBBS year First year

Second year

Fourth year

Fifth year Female anatomy

Puberty Content

Menstrual cycle physiology

Social-cultural context of menstruation

Contraception options

Menopause and HRT

PCOS Hormonal contraception and HRT

Uterine anatomy and menstrual cycle physiology

Menopause

Pathology: Abnormal uterine bleeding, PCOS, endometrial disorders: malignancy, inflammation Menstrual cycle physiology

Contraception options

Amenorrhea

Menorrhagia

Endometrial malignancy Lectures

Anatomy lab Strategies

Videos & media

Q&A workbooks

Lectures

Q&A workbooks Lectures

Lectures

Case-based discussions

Note: These topics were covered in the Obstetrics & Gynaecology and General Practice rotations

Table 7: Selected student responses to ‘In terms of the knowledge and perspective of menstruation you have received, do you think that the JCU MBBS degree could be improved in any way to better prepare you for internship?’

Themes More education on cultural differences n (%) 15 (63%) Examples ‘More info around cultural differences and practices and ways in which these can be overcome’

More education on practice elements 8 (33%)

More education on medical elements 3 (13%) ‘Separate the biological explanation from the social one, as well as showing some understanding of cultural values.’ ‘More information about real things—what a tampon looks like, how often it should be changed. The males in the class don’t really know these things.’

‘It would be interesting to maybe introduce topics such as reusable feminine hygiene products such as the menstrual cup/period underwear, as these have become more popular in recent years.’ ‘A revision of the basic science of menstruation in 4th year and how it related to contraceptives; this felt very rushed in 5th year when contraceptives are such a big part of everyday clinical practice for GPs. More knowledge about menstrual pharmacology and risks, benefits, etc.’