2 minute read

A date with Australian Muslim stories

by AMUST

In February, I left London for Sydney to work on Recipes for Ramadan, leaving one of the most multicultural cities on earth for the most multicultural nation. A non-Muslim, my understanding of Ramadan was half-knowledge. I knew of fasting but didn’t know what iftar meant.

Graduating university last August, I was adamant I would do a year of work and travel to engage with people and places I previously hadn’t. Recipes for Ramadan had my attention. The Australian Muslim community was far from my own, and the project intertwined things I had a pre-existing fascination with: history, ancestry, food.

Advertisement

Mia Jeronimus high-level politics but remember that 1942 was the beginning of the Japanese occupation, 1948 independence and 1962, after a coup d’état, when the socialist government confiscated Ayesha’s father’s metal business and the family’s samosa business began. The lens of personal story really enabled me to get to grips with histories I wasn’t familiar with.

My assumption was that I would learn a lot about Ramadan, Muslim culture, and Islam. I do now know the meaning of the word iftar, and special thanks to the Taheri family for hosting me at theirs. But the stories on the website take you beyond an understanding of the Islamic faith.

By the end of Ramadan 2023, the site will be a portal to 25 different countries and histories outside of Australia by way of migration stories. I leave knowing as much about the small Russian province of Tatarstan as I do about Muslim practices.

When I think of the troubles in Burma, now Myanmar, I don’t think of complex

Just as personal stories inform history, history informs personal stories.

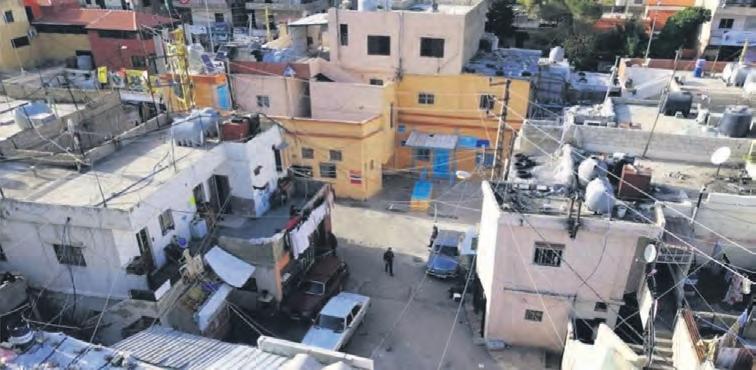

Ayesha’s story gave me an insight into Burmese history, but Lebanese history made sense of the gravity of Sivine’s mother’s decision to leave

Tripoli. Knowing that it was sectarian violence that killed her dream to retire to a flat in El Mina harbour – a dream within her reach until the civil war – helped me grasp the scale of what was at stake in individual lives and to see how external events re-route lives in ways that may later be termed fate. Writing up such stories, placing them in their historical context and realising these experiences are not anomalies has been an education which resonates with my own family’s past. I wrote my undergraduate dissertation about my Dutch grandmother’s experience in a Japanese prisoner of war camp in Java during the Second World War and talking to participants for Recipes for Ramadan provoked my same fixation on the details, patterns, hopes and pains of familial pasts. Affording other families’ histories the same curiosity we do our own is a powerful form of empathy.

Cooking these recipes and reading their stories as something simmers, cooks, browns or rises is not just pseudo travel but pseudo time travel to a place as it once was. Just as music locks in memory, food locks in story, story locks in history. Cooking and photographing recipes for The Guardian’s third series of Recipes for Ramadan, learning about people and places and sealing that learning with taste was a very special shared experience – the virtual iftar it was intended to be.

Learning about what it might mean to be of Lebanese or Russian, Bosnian or Burmese descent, I have seen what it means to be Australian, and what it means to be a multicultural society. Strange how it takes travelling to the other side of the world to have a clearer idea of things at home. I will be returning to London excited for new conversations.

As the poet T S Eliot put it in Little Gidding: “… the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.”

My special thanks to Jane Jeffes, AMUST and Recipes for Ramadan’s contributors for having me.

Mia Jeronimus is an intern on Recipes for Ramadan.