West 22nd Street

York

West

York

West 22nd Street

York

West 21st Street

York NY

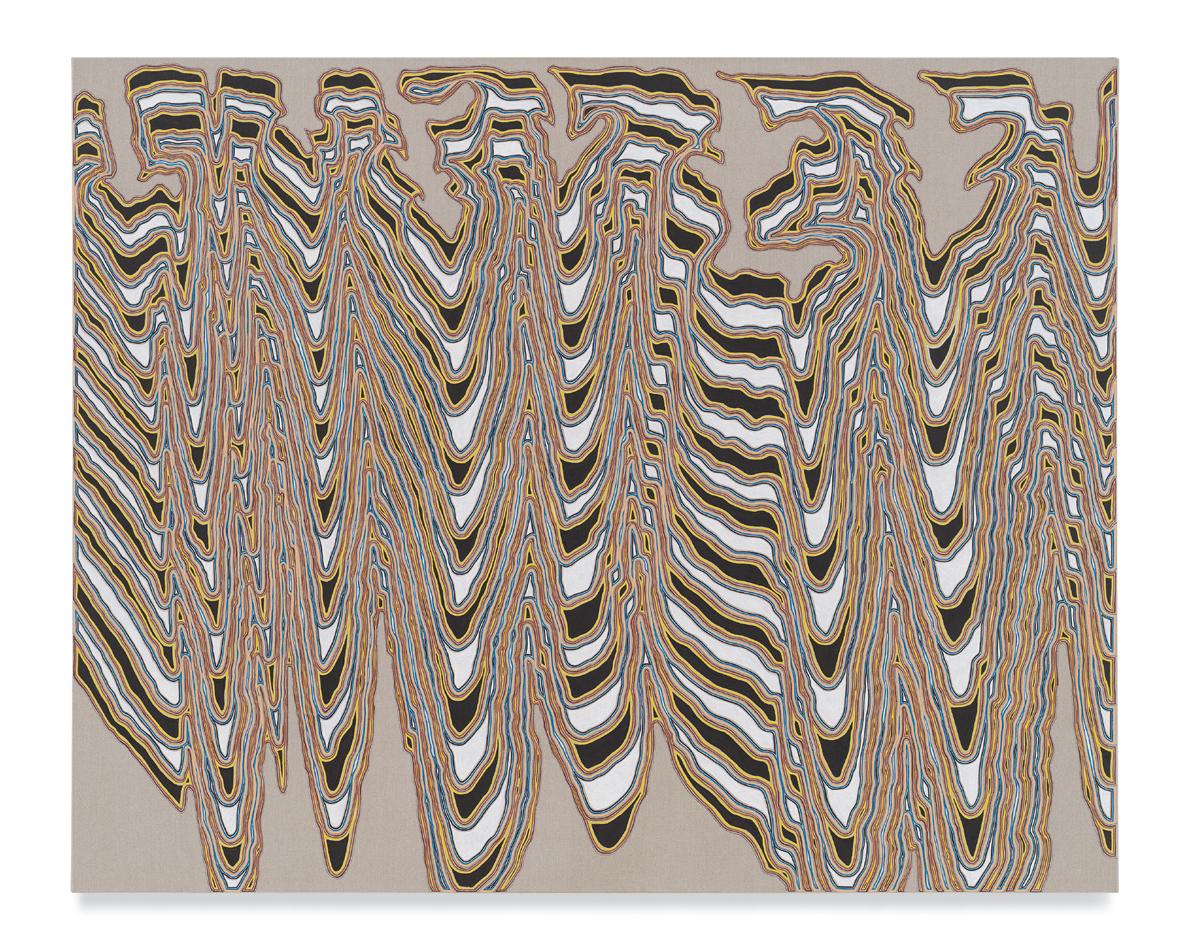

For more than four decades, New York artist James Siena has been creating highly original works that have delighted and puzzled critics with their unrelenting intensity. Siena’s art was the subject of the 2016 solo exhibition Pockets of Wheat at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and it has entered the permanent collections of this and other such prestigious institutions. In addition, his highly graphic creations have garnered him a Guggenheim Fellowship, residencies at the American Academy in Rome and at Yaddo, and a Cahiers d’Art Institute catalogue raisonné.

Siena explains his long-term preference for working without assistants by pointing out that “time is my most important material,”1 and he consequently will o en spend days, weeks, months, and even years painstakingly realizing individual artworks. He characterizes his process as involving “accumulative and iterative picture-making strategies.”2 For some critics, Siena’s paintings and prints recall a number of historical precedents, including Aboriginal painting, Celtic illuminations, Peruvian textiles, early and mid-twentieth-century Geometric Abstraction, and psychedelia; for others they suggest the relatively timeless imagery of contour maps, cellular structures, and diagrams of dynamic physical forces; and for still others they conjure up such contemporary imagery as microchips and abstractly track the many diverging pathways that are created when surfing the Internet. Despite all these potential affiliations, which Siena may have unconsciously internalized a er years of visiting his favorite Manha an museums, including the Museum of National History, I am convinced that his art is far less concerned with advancing a traditional iconography than with building dynamic labyrinths comprised of persistent and continual lines, which viewers need to traverse if his art is to be understood.

Siena has described his compositions in terms of the “path” and the “procedure,” and he underscores these strategies by saying, “I don’t make marks, I make moves.”3 One source for these extended and enmeshed tactics is his early reading of the 1979 book Gödel, Escher, Bach by the cognitive scientist and comparative literature specialist Douglas Hofstadter and the impact its discussion of recursive or self-referential loops had on

1. James Siena, “Hantaï, the Hidden, and the Audacity of Emergence” in Molly Warnock, ed., Simon Hantaï (London: ER Publishing, 2021), p. 21.

2. Siena, “Hantaï,” p. 23.

3. Robert Hobbs, James Siena (New York: Gorney, Bravin + Lee, 2001), pp. 6 and 8.

Siena’s conception of his own work.4 While recursion is widely recognized as crucial to the writing of computer programs, it also signals an immersed way of ideally perceiving Siena’s work.

Before analyzing Siena’s art in relation to recursion, it helps to consider the historical nexus in which he initiated it. The 1980s were an important time for art and science; the two were notably celebrated and critiqued by Laurie Anderson in 1982 in her performance art piece United States Live and its spin-off, the best-selling album, Big Science, in which she subjected herself and her voice to various technologies to create a range of cyborgian personae. Her masks diminished the human while simultaneously extending it into different media, enabling audiences to imaginatively conceive how people might inhabit a post-human world. Anderson’s album closely followed the success of Ridley Sco ’s neo-noir science-fiction film Blade Runner (1982), which was based on Philip K. Dick’s 1968 science-fiction novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? The film is set in a postapocalyptic world populated by humans and Nexus-6 androids, or humanoid robots called replicants. Playing with themes endemic to cybernetics—the mid-twentieth-century science focusing on involved communicative and automatic control systems between humans and machines—both Anderson’s album and Sco ’s film belong to an ’80s fascination with human-machine crossbreeds populating what was then science fiction’s latest subgenre, cyberpunk.

Epitomizing this artistic form, William Gibson’s 1984 dystopian novel Neuromancer fictively crystalized the future in terms of the cyber cowboy Case, who regularly collapsed boundaries between his lackluster everyday reality and the exhilarating artificial world of the Internet as he jacked a simulated version of himself into cyberspace. Concurrent with the publication of Gibson’s novel was Arnold Schwarzenegger’s appearance in the first Terminator film, in which he assumed the role of a futuristic 2029 cyborg assassin who goes back to 1984 in an effort to kill Susan Conner (played by Linda Hamilton) and prevent the birth of her son, who would one day save humankind from extinction. While such popular-culture, cybernetically oriented hits were breathtaking in their cinematic effects, they, together with the increasingly widespread use of personal computers and the continued appreciation of DNA’s dynamic array of genetically encoded information, helped to superannuate the centuries-old Aristotelian emphasis on substance, ma er,

and form, as well as the long-respected Italian Renaissance humanist ideal of centered, rational, and autonomous individuals.

In the early 1980s, when Siena was finding ways to inscribe his early work with recursive, mutating shapes, human beings were no longer being regarded as the measure of all things, and their knowledge was no longer considered to be subjective and all-encompassing. Instead, data was being outsourced to various intelligent machines, like computers, and humanity itself was being subsumed under the aegis of information networks. During this decade, science was viewed as extraordinarily relevant, and science fiction was increasingly understood as predictive not only of the future but also as constituting a stirring way to characterize the present. Moreover, in anticipation of a posthuman world, humanity was being demoted, and efforts to comprehend the future were assuming an unparalleled urgency. A decade later, this quest culminated in the gallerist and curator Jeffrey Deitch’s Post Human traveling exhibition and its accompanying catalog.5 While Deitch focused on figurative works of art, James Siena’s exceedingly abstract work, which he had commenced more than a decade earlier, initiated the project of rethinking posthumanity in terms of recursive processes.

Siena’s emphasis on recursion parallels second-wave cybernetics. Instead of continuing to subscribe to the concept of individual autonomy, this type of cybernetics subsumes human beings under the closure of overarching circular or recursive systems, which are self-generating, so that outcomes serve as inputs for yet additional outcomes, creating an ongoing feedback loop that encircles itself. We might compare this process to the Ouroboros, the ancient image of a serpent biting its tail that signifies the cycle of destruction and rebirth. Similar to DNA, which is self-replicating and recursive, secondorder cybernetics views humans as participating in the much larger system of informationprocessing machines and intelligent technologies. In this field, recursive prostheses proliferate like branching and bifurcating tree limbs: The body is theorized as the mind’s foremost prosthesis, while various technologies assume the role of supplemental appurtenances. Working together, recursive components form assemblages on the order of Siena’s quest “to communicate from my mind to my hand.”6 Thinking is thus of paramount importance for Siena and his art, as he elucidates:

4. Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (New York: Basic Books, 1979).

5. Jeffrey Deitch Post Human (Ostfildern, Germany: Cantz/Deste Foundation for Contemporary Art, 1992).

6. Schwartz, “A Conversation with James Siena, Figure Ground (2013 and 2014), p. 4, h p://figureground.org/a-con versation-with-james-siena/, consulted June 29, 2022.

I could say that I’m interested in the machinery of seeing, or the machinery of thinking. I mean, other people have said that my works “think”— that they are like circuit boards or passages.7

When analyzing Siena’s work, it helps to separate thinking as a human trait from the type of awareness his recursive art generates by characterizing that awareness as cognition and by defining this term as the literary critic N. Katherine Hayles recommends as “...a process that interprets information within contexts that connect it with meaning.”8 In doing so, we move beyond the o en-mistaken emphasis on the decorative appeal of Siena’s paintings in order to dwell on their far more substantial function of acting as cognitively empowered machines. “The way they act as machines,” Siena has pointed out, “is you have to find your way into them and find your way out of them.”9 He reinforced this idea by pointing to the type of close observance viewers must undertake if they are to understand his art’s cognitive power. “Well, the work starts to do the thinking, in a way,” he told the critic and artist Chris Martin. “The work generates more work. If you need ideas, look at the work.... They are like static machines. When they are moving that means they are doing something to you.”10

Thus, instead of perceiving Siena’s work as Gestalt principles capable of stamping holistic images on observers’ retinas, his viewers are encouraged to trace visually the art’s linear development by working slowly and methodically through his “paths” and “procedures” in order to trace each of the paintings’ ripples, curls, folds, furrows, and swells as his circulating linear motifs roam, surge, careen, and undulate across his painted surfaces. Only by a entively approaching their linear movements and developments will viewers be able to appreciate the artist’s algorithmic pa erns—the initial set of rules with which Siena has noted beginning each piece—and ascertain how they have coalesced into recursive and active cognitions.

Central to Siena’s decidedly contingent art are the gaps between these initial instructions, which he gives himself, and his ultimate creations; between the two are the all-important breaches he refers to as “...the mental focus [that]...emerges as the very subject of the artwork.”11 Meaning in Siena’s art can therefore never be anticipated at the outset,

7. Noelle Bodick, “Perspectives: James Siena on the Process behind His Rigorous, Rule-Based Artworks,” Artspace (February 25, 2014), p. 1.

8. N. Katherine Hayles, Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive Nonconscious (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2017), p. 22. Her definition builds on the one offered by John Mingers in Self-Producing Systems: Implications and Applications of Autopoiesis (New York and London: Plenum Press, 1995), p. 46. According to Mingers, “Cognition is seen as a process of symbol manipulation and information processing.”

9. Efi Mihalarou, “Art Cities: Paris—James Siena,” Art View h p://www.dreammachine.com/?p=51911, consulted June 29, 2022.

Dyscopioid, 2022 Ink and graphite on paper

because of the wavers of his hand as well as the pauses and breaks in his algorithms that instantiate a very human presence in the assemblages constituting his art. “I am happy to mess up the idea halfway through the execution,” Siena has candidly told. “I am not stuck on blandly following an idea. I want to see something, but I also want a li le slippage. I want something to get close to breaking down.”12

Siena’s statement provides additional insight into why he prefers working without assistants, for their input would preclude the free play of his own hand, which he regards as crucial to the creation of his art. Slippage provides occasions for randomness that open his initial visual algorithms to contingencies and potentially a greater range of meaning. “Through mechanisms such as artworks, pieces of music, buildings, inventions,” Siena has a ested, “we arrive at a deeper understanding of reality’s slippery nature, its unpredictability, and, most of all, its complexity.”13

In early 1983, soon a er Siena moved to New York a er graduating from Cornell University with a B.F.A., he became known as one of the seven members of the performance collective Watchface, while continuing to maintain a very active studio practice during that time. A er the birth of his son Joe in 1988, he decided to give up his performance work for the privacy of drawing, painting, and sculpting in his studio. But even today, the

10. James Siena, “James Siena with Chris Martin,” The Brooklyn Rail, h ps://brooklynrail.org/2005/1/art/jamessiena-with-chris-martin, consulted July 2, 2022, p. 5.

11. Hovey Brock, “James Siena: Leviathan,” (2014) h ps://cometogethersandy.com/james-siena/, consulted June 29, 2022.

12. James Siena, “Interview with James Barron,” (Rome: March 2013), typescript, n.p., James Barron’s archives, South Kent, CT.

13. Schwartz, “A Conversation with James Siena,” p. 20.

7

all-important legacy of his five years of performing is evident in the bifurcating, diverging, and diversifying paths of lines found in his drawings and paintings, and it continues to imbue his intricately reticulated fields with concentrated energy. When viewers closely examine his art, they are, in a sense, engaging in their own performance of it, and their ensuing conclusions about how Siena’s intense oscillating and percussive shapes function as art provide additional opportunities for complementing its realization and meaning. Because these two very different yet necessary performative aspects of the work—the first enacted by the artist and the second undertaken by his viewers—are so crucial to its realization, it helps to take note of Siena’s observation:

It’s the “crooked” that makes that [art] human. Because the hand of the person making the crooked lines is going to be different every time. It is the responsibility of the viewer to respond to the humanity of the artist no ma er what, because it’s always there.14

In other words, Siena and his recursive works form one system, while his viewers, in the process of being engaged with his art, form another. In both, recursive circling constitutes a cognitive mode.

When Siena assumes the viewer’s role in encounters with other artists’ works, he looks for evidence of cognition—that is, a mind at work, which in turn catalyzes the workings of his own. Insight into this type of apperception is found in Siena’s brief essay on Albrecht Dürer’s second self-portrait, painted in 1498 a er this artist’s first trip to Italy. Rather than dwelling, as many writers have done, on this twenty-six-year-old German’s pictorial elevation of his social position on a par with some contemporary Italian Renaissance painters, Siena concentrates on the act of cogitating that Dürer’s self-portrait catalyzes.

“This remarkable painting is about a mind manifesting, supremely confident,” Siena writes, “but it’s also about a mind scrutinizing itself. This is, a er all, what all artists do, to this day.”15 In Siena’s estimation, then, Dürer’s self-portrait is self-aware, self-created, highly recursive, and only open to viewers in so far as they are willing to enter into the elaborate process of protracted gazing and reflective thinking this work invites. We can refer to this affiliation of art and viewer as “structural coupling” by following Hayles’s assumption that, “...the observer can observe only because the observer is structurally coupled to the phenomenon she sees.”16

14. Bodick, “Perspectives: James Siena on the Process behind His Rigorous, Rule-Based Artworks,” p. 3.

15. James Siena, “James Siena on Albrecht Dürer,” Painters on Painting (August 13, 2015), h ps://paintersonpaintings .com/james-siena-on-albrecht-durer/, consulted June 29, 2022.

It is not surprising that Siena invokes a machinic metaphor when discussing his own work, as he has enjoyed collecting antique and vintage typewriters over the past few decades. Remarkably, he has amassed over a hundred of these once ubiquitous pieces of equipment, and he enjoys tinkering with some of them so that he can use them to type le ers and address envelopes. “I am interested in the machine/human interface,” he told the artist and critic Joe Fyfe, no doubt including typewriters in this assertion when he added a phrase about “the ten fingers extending from the mind to the mechanism.”17 In this way, he endows these machines with the status of cognitive pieces of technology.

Siena’s long-term penchant for these outmoded devices paid big dividends in 2013 when he moved to Rome to assume a fellowship at the American Academy in Rome. The previous November, he had broken the wrist of his painting hand, and when he found one of Olive i’s Studio Typewriters for sale at the Porta Portese flea market, he was encouraged, a er months of therapy, to begin improvising. He started with the parenthesis key of his computer to create overall undulating shapes resembling “sound waves traveling back and forth”18 in emails to friends before beginning to work with his recently acquired Olive i Studio Typewriter, with its wonderfully serendipitous name that can be interpreted as a reference to the artist’s workplace. Siena repurposed this typewriter as a drawing tool for a series of works that began with the repetition of individual keys before graduating to numbers and palindromes. By returning in these typewriter drawings to an out-ofdate technology, Siena was able to allude to pervasive symbiotic cognitive assemblages involving human beings, computers, and the Internet.

In a series of entirely logical yet unpremeditated steps, James Siena moved from several decades of embellishing machine-like metal plates with sign painters’ enamel—a possible metaphor for art’s semiological reach—on his small-scaled, highly compressive, and labyrinthine paintings, which are themselves metaphoric blueprints for thinking as a recursive process, to embracing typewri en signs, le ers, and words for his typewriter drawings. In 2018, he challenged himself to initiate a new direction when he began working on large-format canvases. In these new works, Siena relied on acrylic paint’s potential for achieving both liquidity and mobility, which enabled him to create increasingly elastic forms that appear to expand and contract as they “visually reverberate,” in the artist’s words, to create “ultrasonic ripple effect[s].”19 With these works, Siena’s long-term fascination

16. N. Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1999), p. 142.

Joe Fyfe, “Strange Loops,” Art on Paper 7, no. 4 (January-February 2003), p. 44.

Siena, “Interview with James Barron,” n.p.

with music comes to the fore as his recursive and contingent forms resonate, forming vibrating dri s that pulsate as they extend across the surfaces of canvases, flickering, shimmering, and fluctuating in their varied simulations of acoustical effects. The sheer wealth of visual data in these paintings continues to generate informational overload or entropy in viewers, which is evident in different degrees in all Siena’s work, but with his preference for a new type of visual music he does so in a more melodic manner than he did in his earlier art. Writing of the heightened entropic state he still wishes his imagery to invoke in viewers, Siena prioritizes the “granular scale” he vivifies and amplifies in his compositions, so they might approach a new form of mathematical sublimity:

So long as visual information is evenly distributed at a granular scale, pa erning as such doesn’t typically generate overload; but when the grains that make up that information are nonrepetitive, the visual cortex short-circuits in a vain a empt to discern an organizing principle or fundamental logic. At that point things get interesting. The mind of the viewer adjusts and manages to absorb effects that previously were too much to take in. That is a condition I aspire to generate in a viewer. 20

In art that encompasses more than forty years of concerted activity, James Siena has turned from conceiving pa erns as nouns, and thus static decorative compositions, to regarding pa erning as a dynamic verb, so that engaging tensions ensue between his recursive forms that expand, twist, vacillate, and unfold in delightful and hypnotic sequences. Siena, I should mention, takes a dim view of the word pa ern, asserting, “in my work I’m not thinking about pa erns—I don’t like that word.”21 Thus, when one uses the word pa ern to characterize his art, one is inadvertently undermining its creative energy and the ongoing perception of its consequent forces that are germane to its proper functioning. Moving from this word, with its customary connotations of visual reification, to more supple ones enables us to stop relying on intelligence—commonly understood as a general mental ability and o en used as a defining quality of Siena’s work—and to focus instead on how his art functions cognitively in several ongoing processes that involve not only the artist and his preferred media but also his viewers. The three serve as forceful adjuncts to the enduring creation of recursive artworks capable of creating mutual dependencies; together, they create an ongoing complementarity as well as an exhilarating and wellconsidered undermining of the traditional artist’s autocratic oversight.

19. Phoebe Hoban, “James Siena: Painting,” Riot Material: Art, Word, Thought, h ps://www.riotmaterial.com/ james-siena-painting/, consulted June 29, 2022.

20. Siena, “Hantaï, the Hidden, and the Audacity of Emergence,” p. 23.

21. Bodick, “Perspectives: James Siena on the Process behind His Rigorous, Rule-Based Artworks,” p. 3.

Infolded

Sessile Amissae,

Dyscopia,

Palimp, midplane, 2021 Colored pencil on linen

x 16 inches

x 40.6 cm

Termindial, 2021

pencil on linen

inches

Chloasmia,

Born in 1957 in Oceanside, CA

Lives and works in New York, NY and Otis, MA

1979

BFA, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

2022

Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY 2021

“Vergence,” Baronian Xippas, Brussels, Belgium

2020

“Phased Resonators & Reciprocating Transitions: Paintings and Watercolors,” Ratio 3, San Francisco, CA

2019

“Cascade Effect,” Galerie Xippas, Paris, France “Resonance Under Pressure,” The Print Center, Philadelphia, PA

“Project Room: James Siena,” Pace Prints, New York, NY Pace Gallery, New York, NY

2017

Pace Gallery, New York, NY

2016

“Pockets of Wheat,” Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

2015

Xippas Art Contemporain, Geneva, Switzerland “New Sculpture,” Pace Gallery, New York, NY “Typewriter Drawings,” Hiram Butler Gallery, Houston, TX “Labyrinthian Structures,” Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

2014

“Sequence, Direction, Package, Connection,” Dieu Donné, New York, NY Galerie Xippas, Paris, France

2011

Pace Gallery, New York, NY

2010

Daniel Weinberg Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

Pace Prints, New York, NY

“From the Studio,” Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

2009

“Works by Master Artist James Siena,” Atlantic Center for the Arts, New Smyrna Beach, FL

2008

PaceWildenstein, New York, NY

2007

“Big Fast Ink: James Siena Drawings, 1996 – 2007,” University Art Museum, University of Albany, New York, NY

“Prints and States,” Pace Prints, New York, NY

“As Heads is Tails,” Mario Diacono Gallery, Boston, MA “Recent Editions,” Greg Kucera Gallery, Sea le, WA

2005

“New Paintings and Gouaches,” PaceWildenstein, New York, NY

“Ten Years of Printmaking,” William Shearburn Gallery, St. Louis, MO

2004

“Selected Paintings and Drawings 1990–2004,” Daniel Weinberg Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

2003

Gorney Bravin + Lee, New York, NY

“James Siena: Drawing and Painting,” Walter & McBean Galleries, San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA; traveled to University of Akron, Akron, OH

2002

“Recent Paintings,” Daniel Weinberg Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

2001

“James Siena: 1991-2001,” Gorney Bravin + Lee, New York, NY

2000

“Project Room,” Gorney Bravin + Lee, New York, NY

Daniel Weinberg Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

Daniel Weinberg Contemporary Art, San Francisco, CA

1997

Cristinerose Gallery, New York, NY

1996

Pierogi 2000, Brooklyn, NY

1986

J. Noble Gallery, Sonoma, CA

2022

“Among Friends: Three Views of a Collection,” FLAG Art Foundation, New York, NY

“James Siena & Katia Santibañez,” Cheymore Gallery, Tuxedo Park, NY “Two to Tango,” Bernay Fine Art, Great Barrington, MA

2019

“Daedalus’ Choice,” Galerie Xippas, Paris, France

“New Typographies: Typewriter Art as Print,” The Print Center, Philadelphia, PA

2018

“The Annual Professional Painters’ Exhibition,” Century Association, New York, NY

“The Heckscher Collects: Recent Acquisitions,” The Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, NY

“The New Members Exhibition,” Century Association, New York, NY

“Out of Control,” Venus Over Manha an, New York, NY

“Principia Mathematica,” Pace Gallery, New York, NY

“The Projective Drawing,” Austrian Cultural Forum, New York, NY

“Island Press: Recent Prints,” Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis, MO

2017

“Dialéctica,” Galerie Xippas, Paris, France

“The State of New York Painting: Works of Intimate Scale by Colorists,” Kingsborough Art Museum, Brooklyn, NY

“In the Absence of Color: Artists Working in Black and White,” Hollis Taggart Galleries, New York, NY

“Why Draw? 500 Years of Drawings and Watercolors,” Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, ME “Almost Nothing,” James Barron Art, Kent, CT

2016

“Random X,” Galerie Xippas, Punta del Este, Uruguay “Abstracción,” Galerie Xippas, Montevideo, Uruguay “Going Home,” Bortolami Gallery, New York, NY

“Big Art / Small Scale,” Philip Slein Gallery, St. Louis, MO “Talking on Paper,” Pace Gallery, Beijing, China

2015

“Systems and Corruptions,” National Exemplar Gallery, New York, NY “Intimacy and Discourse: Reasonable-Sized Paintings, Part I,” Mana Contemporary, Jersey City, NJ “Linear Elements: Alain Kirili and James Siena,” OMI International Arts Center, Ghent, NY

“On the Square Part II,” Pace Gallery, New York, NY “Drawings and Prints, Selections from the Permanent Collection,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

“SKIN (Part 1),” National Exemplar Gallery, New York, NY “Summer Group Show,” Pace Gallery, New York, NY “Black/White,” Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY “Eureka,” Pace Gallery, New York, NY “Invitational Exhibition of Visual Arts,” American Academy of Arts and Le ers, New York, NY

“Back to the Future Part II,” Life on Mars Gallery, New York, NY

2014

“Line: Making the Mark,” Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX

“Space Out: Migration to the Interior,” Red Bull Studios, New York, NY “Orly Genger and James Siena: Works on Paper,” Sargent’s Daughters, New York, NY

“Pierogi xx: Twentieth Anniversary Exhibition,” Pierogi, New York, NY

“In the Round,” Pace Gallery, New York, NY “Oblique Strategies: Track 2,” Peter Fingesten Gallery, Pace University, New York, NY

“The Age of Small Things,” Dodge Gallery, New York, NY

2013

“Heat Chaos Resistance: It’s Time to Live in the Sca ered Sun,” Radiator Gallery, New York, NY

“Come Together: Surviving Sandy Year 1,” Industry City, Brooklyn, NY

“System/Repetition,” Russell Bowman Art Advisory, Chicago, IL

“Image and Abstraction,” Pace Gallery, New York, NY

“Abstract Generation: Now in Print,” The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

“The Annual: 2013,” National Academy of Art, New York, NY “Geometric Abstraction,” Pace Prints, New York, NY

2012

“Diamond Leaves: 86 Brilliant Artist Books from Around the World,” Central Academy of Fine Arts Museum, Beijing, China

“Summer Group Show,” Pace Gallery, New York, NY

“Print/Out: 20 Years in Print,” The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

“Paper A-Z,” Sue Sco Gallery, New York, NY

“Recent Editions,” Pace Gallery, New York, NY “6 Abstract Painters,” DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY “50 Years at Pace,” Pace Gallery, New York, NY “Couples,” Ferrin Gallery, Pi sford, MA

“NeoIntegrity: Comics Edition,” Museum of Comics and Cartoon Art, New York, NY

“The Visible Vagina,” David Nolan Gallery, New York, NY “On the Square,” PaceWildenstein, New York, NY

2009

“A Walk on the Beach,” PaceWildenstein, New York, NY

“Pa erns Connect: Tribal Art and Works by James Siena,” Pace Primitive, New York, NY

“Morphological Mutiny,” Galerie Nolan Judin, Berlin, Germany; traveled to David Nolan Gallery, New York, NY

“New at the Morgan: Acquisitions Since 2004,” The Morgan Library and Museum, New York, NY “Talk Dirty to Me,” Larissa Goldston Gallery, New York, NY

2008

“Chroma,” Ruth S. Harley Center Gallery, Adelphi University, Garden City, NY

“Revision, Reiteration, Recombination: Process and the Contemporary Print,” College of Visual Arts, St. Paul, MN

“Sensory Overload: Light, Motion, and the Optical in Art since 1945,” Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, WI

“A ention to Details,” FLAG Art Foundation, New York, NY

2007

“All for Art! Great Private Collections Among Us,” Museé des beaux-arts de Montréal, Montréal, Canada “Neointegrity,” Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY

“Judith Linhares/James Siena,” University Art Museum, State University of New York, Albany, NY

“Works on Paper,” Reynolds Gallery, Richmond, VA “Tara Donovan, Sol Lewi , Robert Mangold, James Siena: Minimalist Prints,” Augen Gallery, Portland, OR

“Not For Sales,” P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, Long Island City, NY “Lateral A itudes,” Raritan Valley Community College Art Gallery, Somerville, NJ

2006

“Drawing Through It: Works on Paper from the 1970s to Now,” David Nolan Gallery, New York, NY

“Dieu Donné Papermill: The First 30 Years,” C.G. Boerner, New York, NY

“Contemporary Masterworks: Saint Louis Collects,” Contemporary Art Museum, St. Louis, MO

“The Compulsive Line: Etching 1900 to Now,” The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

2005

“James Siena by Chuck Close and James Siena Prints,” Pace Prints, New York, NY “Group Exhibition,” PaceWildenstein, New York, NY

“237th Royal Academy of Art from Madeline & Les Stern,” Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

“New Acquisition Installation,” Johnson Gallery for Drawings and Prints, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

“Drawings from the 1960s to the Present,” Daniel Weinberg Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

“Logical Conclusions: 40 Years of Rule-Based Art,” Pace Wildenstein, New York, NY “two d,” Green On Red Gallery, Dublin, Ireland “Super Cool,” Kathryn Markel Fine Arts, New York, NY “Sets, Series, and Suites: Contemporary Prints,” Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

2004

“Drawing a Pulse,” Slusser Gallery, School of Art and Design, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI

“Summer 2004,” PaceWildenstein, New York, NY

“The 2004 Biennial,” Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY “Endless Love,” DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY

2003

“Black White,” Danese, New York, NY

2002

“The Fall Line,” OSP Gallery, Boston, MA

“New Editions and Monoprints,” Pace Prints, New York, NY

“The 177th Annual: An Invitational Exhibition,” National Academy of Design Museum, New York, NY

“New Editions,” Senior & Shopmaker Gallery, New York, NY

“On Paper,” Daniel Weinberg Gallery, Los Angeles, CA “The Tipping Point,” Locks Gallery, Philadelphia, PA

2001

“Repetition in Discourse,” Painting Center, New York, NY “Accumulations,” School of Art Gallery, Kent State University, OH

“BOXY,” Dee/Glasoe Gallery, New York, NY

“By Hand: Pa ern, Precision, and Repetition in Contemporary Drawing,” California State University, Long Beach, CA

2000

“Art on Paper,” Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC “Mapping, Territory, Connexions,” Galerie Anne de Villepoix, Paris, France

“Fluid Flow,” Tames Graham and Sons, New York, NY “Invitational Exhibition,” American Academy of Arts and Le ers, New York, NY

“Greater New York,” P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, Long Island City, New York, NY

1999

“Cyber Cypher Either End,” Mario Diacono Gallery, Boston, MA

“Invitational Exhibition,” American Academy of Arts and Le ers, New York, NY “Pa ern,” Graham Gallery, New York, NY

“Trippy World,” Baron/Boisante Gallery, New York, NY

“New Work: Painting Today, Recent Acquisitions,” San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA

2021

Guggenheim Fellowship in the Fine Arts, John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, New York, NY 2015

Residency, Fundación Casa Wabi, Oaxaca, Mexico 2013

Resident Fellow, American Academy in Rome, Rome, Italy 2011

Elected to the National Academy of Design, New York, NY 2004

Elected to Membership, Corporation of Yaddo, Saratoga Springs, NY 2000 Louis Comfort Tiffany Award, New York, NY Arts and Le ers Award in Painting, American Academy of Arts and Le ers, New York, NY 1998

Purchase Award, American Academy of Arts and Le ers, New York, NY 1995 Grant, New York Foundation for the Arts, New York, NY 1979

Charles Goodwin Sands Medal, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 1977

Edward Durell Stone Award, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, ME

Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, ME

Daum Museum of Contemporary Art, State Fair Community College, Sedalia, MO

Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, IA

Hammer Museum, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA

The Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, NY

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH

Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO

McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, WI

Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.

Pérez Art Museum Miami, Miami, FL

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA

Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln, NE

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

20 October – 26 November 2022

Miles McEnery Gallery 525 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2022 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved Essay © 2022 Robert Hobbs

Noted art historian Robert Hobbs is the author of over 50 books and major catalogue essays on modern and contemporary art. He has served as Associate Professor at Cornell University, long-term Visiting Professor at Yale University and has also held the Rhoda Thalhimer Endowed Chair, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Anastasija Jevtovic, New York, NY

Photography by Christopher Burke Studio, New York, NY Dan Bradica, New York, NY

Color separations by Echelon, Los Angeles, CA

Catalogue designed by McCall Associates, New York, NY

ISBN: 978-1-949327-90-8

Cover: Carnosine, (detail), 2022 Endsheets: Dyscopioid, (detail), 2022