MICHAEL REAFSNYDER

My wife asked me last week, “Do you know what you’re going to say about Reafsnyder?”

I said, “I don’t. I’m thinking about it. I’m thinking about him. I mean I’m thinking about his paintings.”

I had been thinking about him, though, not just his paintings. I first heard about Michael Reafsnyder when I was in graduate school. He had been in the same program a handful of years earlier. A good friend of mine, who struggled to make gloopy paintings something other than gloopy paintings, talked about him all the time. Reafsnyder was a model back then, in 1999, in that place, Los Angeles, of a kind of painter that we wanted to be. I wasn’t even a painter at the time, and I wanted to be like him.

He had the endorsement of figures whose lectures we’d attended and whose books we’d read. He was obviously engaged with history, but he wasn’t shackled by it. How could you make abstract expressionism that wasn’t contaminated with the awkward self-consciousness of knowing exactly what a drip signifies? By the 1960s, Roy Lichtenstein, with his hard-edge cartoon of a saturated Willem de Kooning brushstroke, was already making jokes about the impossibility of using deep personal feeling to produce something that looked like a company logo for pathos. So how could this guy, just a few years older than we were, have cracked the code of being able to use paint however the hell he wanted to?

You’ve got to understand that the grad program we attended, at Art Center College of Design, was led by Mike Kelley and Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe—two forces with terrifying capacities for art historical recall and completely opposed and ironclad, idiosyncratic theories of the causes, ramifications, and meanings of anything and everything that had happened in art in the last 100 years.

Reafsnyder,

Reafsnyder,

Every image or object you made would be dissected. Paintings would be verbally flayed to the fibers of their historical anatomy. You’d find you’d made reference to the French Supports/Surfaces painters or an obscure Gina Pane performance, even though you had never heard of them. Then you had to read up on them in order to defend or jettison this one minor move you’d made in your work.

Yet somehow Reafsnyder had managed, in this grim arena, to make painterly, brushy, gestural, all-over abstraction and not get bogged down into recapitulating or “critiquing” the histories of Jackson Pollock or de Kooning. A territory was staked out where those ways of painting could be deployed for other purposes.

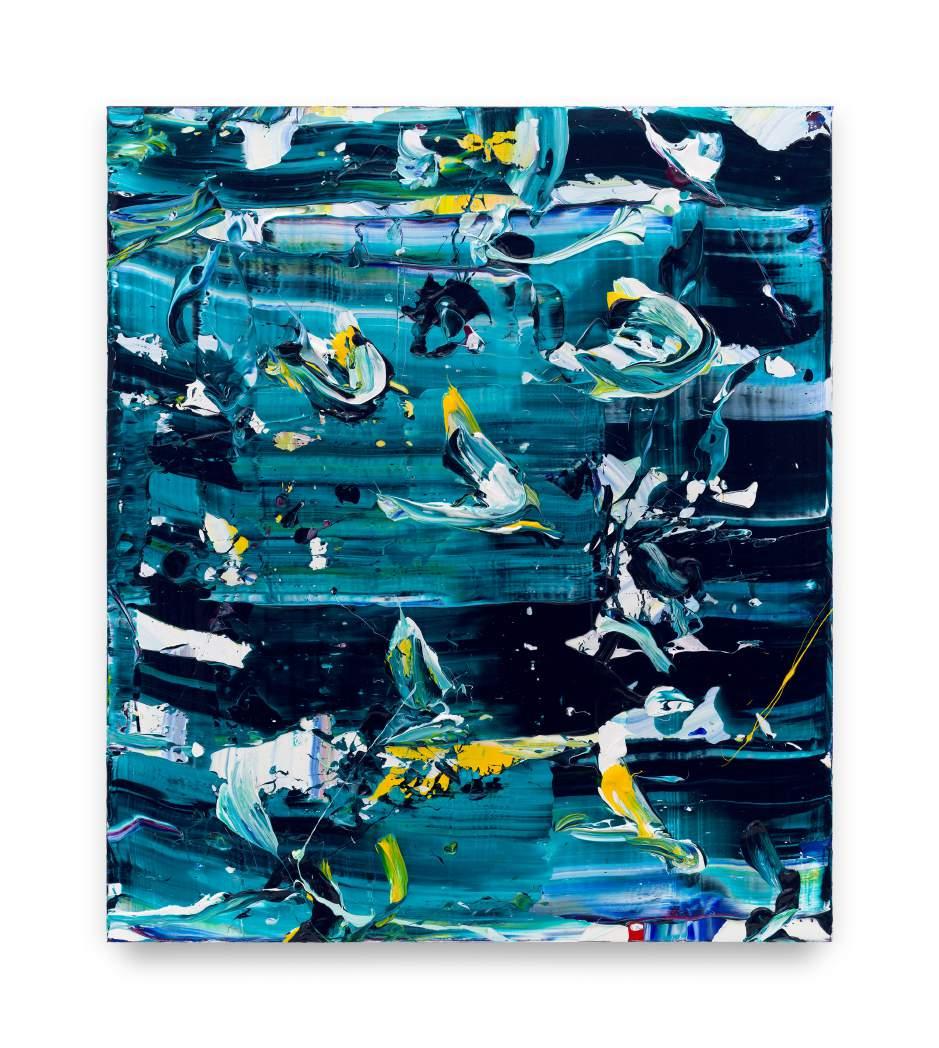

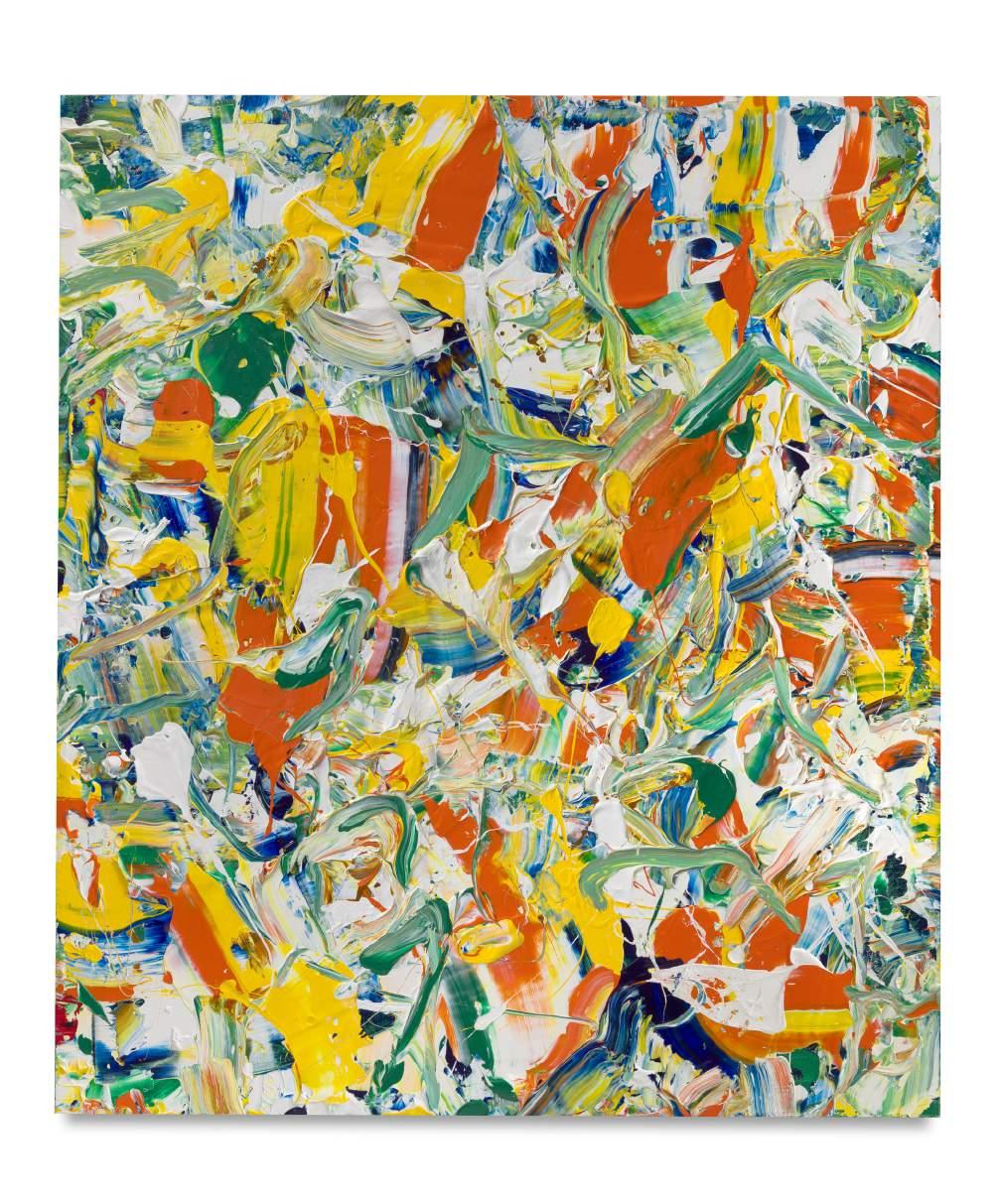

It turns out it was both simpler and harder than we thought. A press release from a 1997 show asserts that his paintings are about “muddiness”—the implication being that the paint is like colored mud. In 2009, Reafsnyder was in a major group exhibition called Electric Mud, about the affinities of paint and clay. In it, he showed ceramics that were as malleable-seeming and as fluid as his paintings— or maybe it’s better to say that his paintings were as thick and viscous as clay.

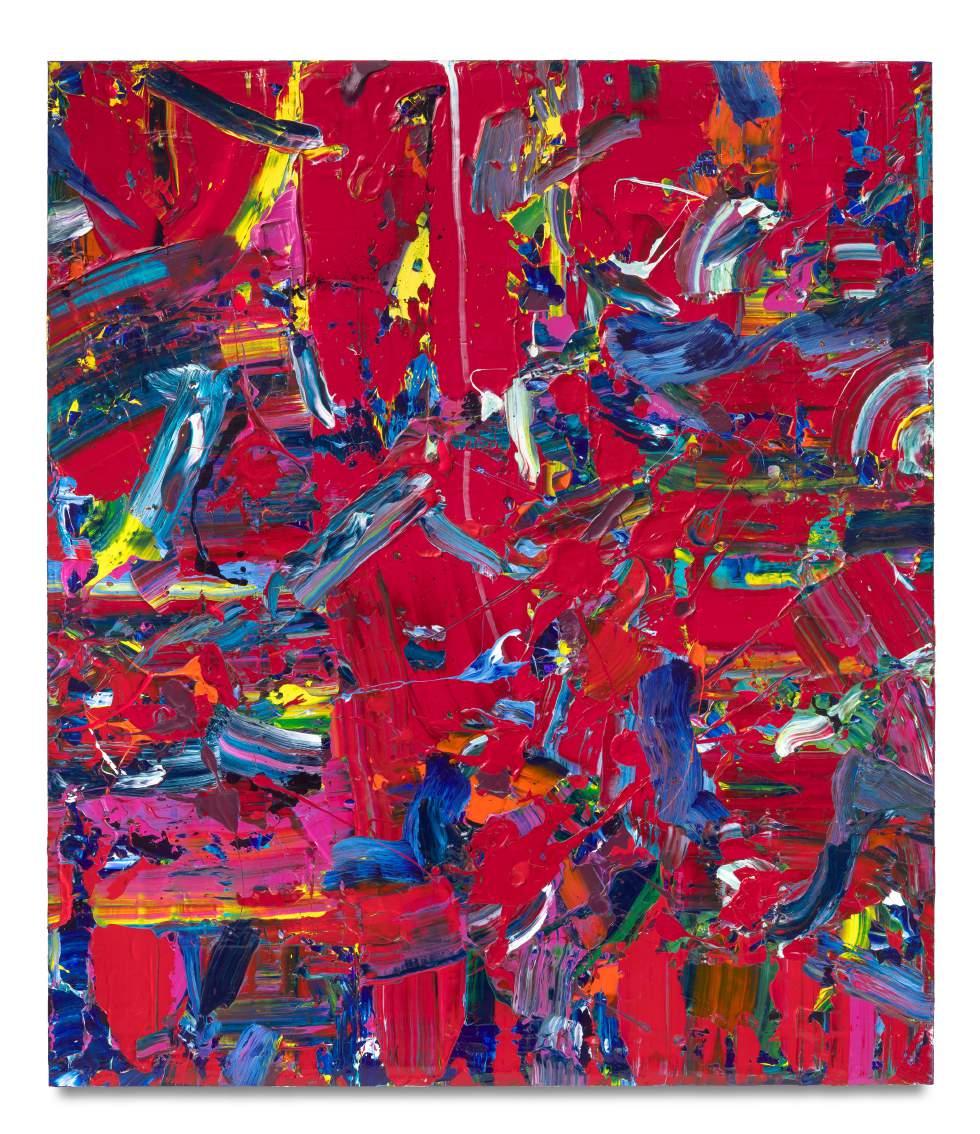

Treating paint as a substance—a thick, soft material, brightly colored and of varying translucency—dodges the historical problem embedded in the received wisdom about gestural abstraction. Reafsnyder’s paintings are neither brush marks as manifestations of the interior emotional state of the painter, nor a purification of the medium down to form and color divorced from any representational content. Instead, he gets to an older, more primal historical problem. A prehistorical problem.

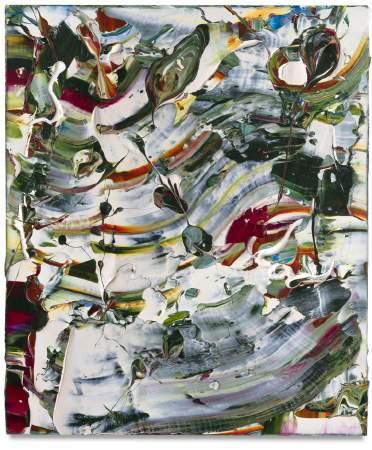

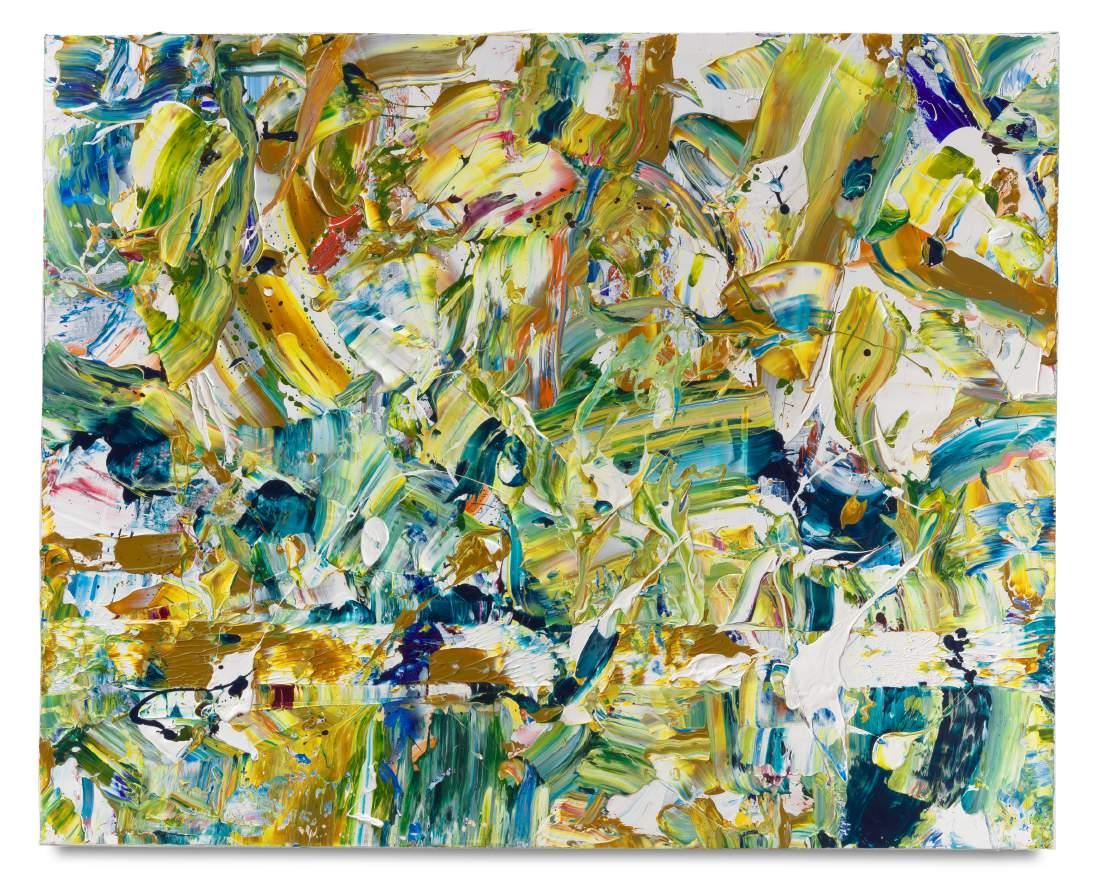

In this new show, there’s a painting I keep returning to titled Mud Buggy (2023), Algae shades of green smash into wine-y quinacridone red; cool grays screech around the corner and scrape the fender of some cadmium. The overt reference to wet earth in the word Mud comes up against a less clear reference in the word Buggy. Is it an odd old car? An insect-infested swampland? The painting evokes both in a way. Reafsnyder is asking us what we think the mud can do? And that’s the magic in his paintings: Adherence to the principles of what mud can do opens up possibilities for formalism, creeps up on representation, reminds us that the highest orders of art, even with the technology of polymers and synthetic pigments, are linked to the natural earth of cave painting.

Reafsnyder navigates around what was called expressionism by ignoring pathos as a problem for painterly abstraction. It’s sort of maddening that he can just say he’ll do it the way he wants to and not how other people did it, but it’s pretty convincing in the end. His colors never feel like personal trauma or the postnuclear terror of the late 1940s. The way he gets around the problems of formalism is trickier.

The move to total abstraction was described by Clement Greenberg as a removal of “imitation” and any relationship to the literary, so that the medium could do its work purely as form and not as content.1 This theory ignores the way we see faces in clouds and wood grain, but for most people a so-called nonrepresentational picture starts to look like something if you stare long enough. The idea of nonrepresentation ignores the way every image will eventually start to evoke some other image. And ultimately, it ignores that we have been there before.

When painting began (on cave walls, on people’s bodies), it was done by mashing up colored soil. That transformation from mud to painting instantly has content beyond form. Even if you don’t start to see a face in the drips and swirls of the wet dirt, there is at least the content of culture being invented.

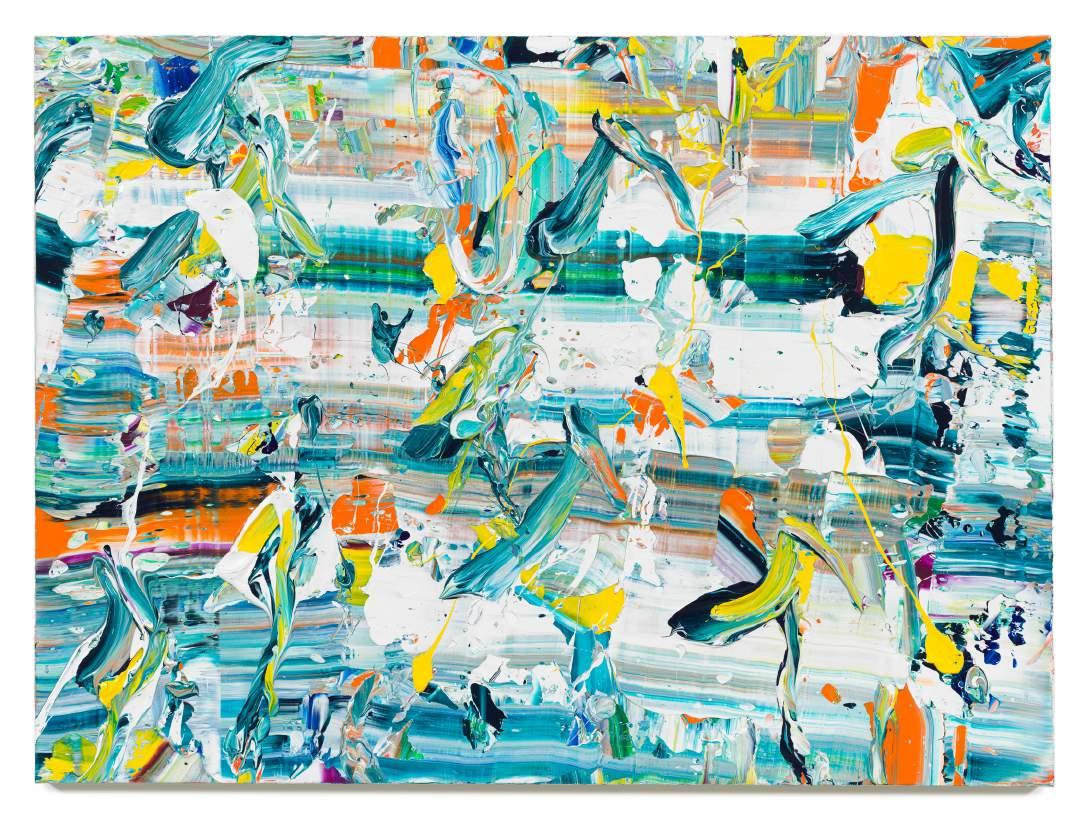

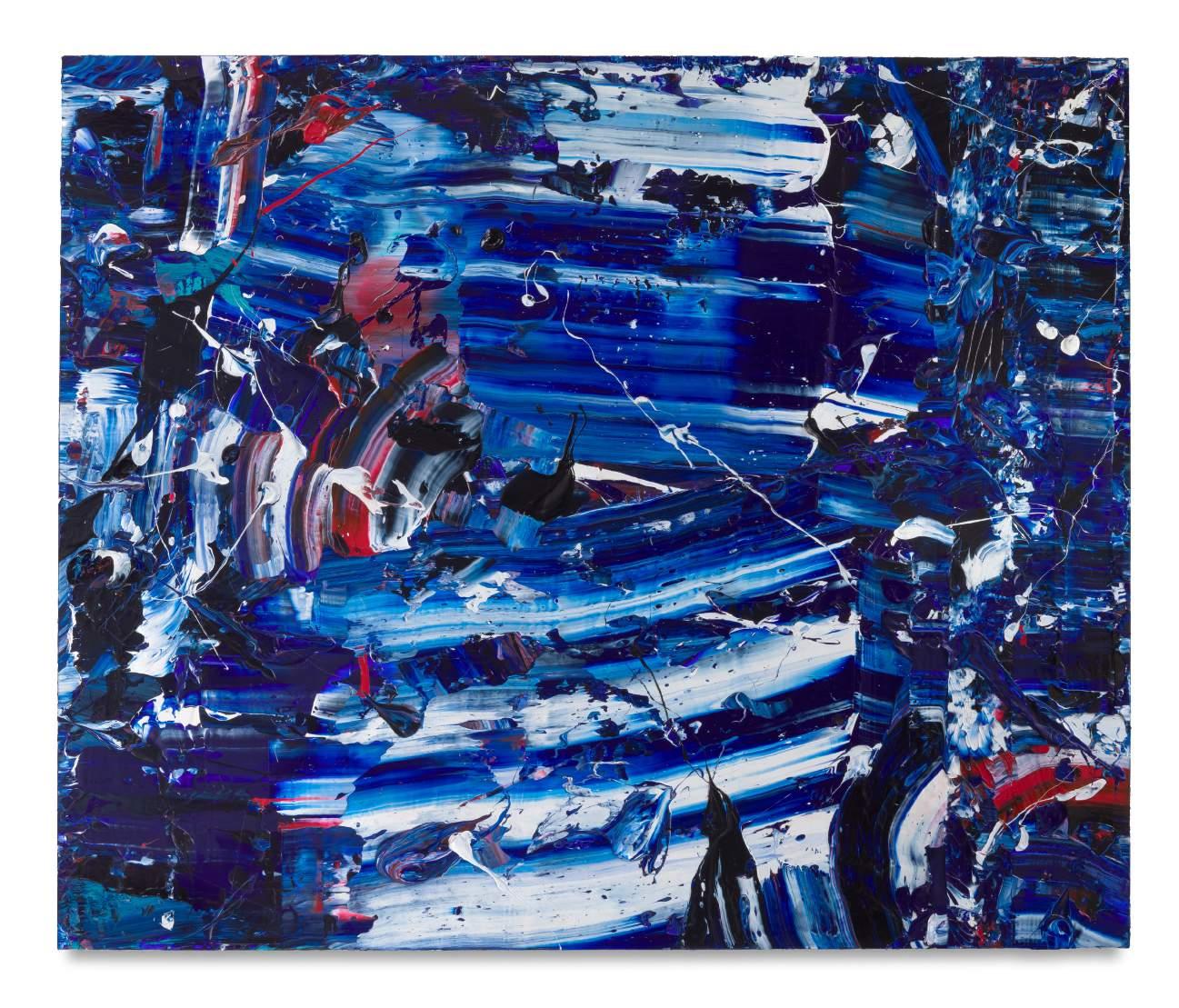

Reafsnyder’s titles evoke places and things. The canvases sure look like abstraction at first glance, but names like Blue Lagoon (2023), Sunday Picnic (2023), and Pacific Plunge (2023), make you want to look for some hint of landscape or architecture on which to get a foothold. Much like Richard Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park paintings, where I can be absolutely certain I can make out a hilly grid of streets in San Francisco only to have the grid flash off into a patchwork of colors and shapes just as my mind was starting to get hold of it, Reafsnyder’s paintings are mesmerizing, and withhold their referent tantalizingly. They work on the eye’s desire to find something to land on and recognize.

By letting paint be paint, Reafsnyder manages to let the chain of signification add link after link. The mud connects to the cave, the birthplace of culture, to a chunk of rock, to a wave on a shore, to water crashing and slapping against the rock, making gelatinous pale green flecks and blobs of foam, to dense sand slowly absorbing water going from glossy to flat and planar, a concrete slab, the side of a house, a clean white wall, a painting hanging on that wall.

I met Reafsnyder a little more than ten years ago. I had started painting after years of avoiding it at all costs. By then, I had enough distance from graduate school for the fear to have subsided, and I came up with a decent idea for a painting or two. My paintings met with enough success that I was invited to be a visiting artist at the institution where Reafsnyder was a professor. When we met, we discussed the shared procrustean bed of our grad school experience and the anxieties of influence. Then, I was lucky enough to be on a thesis committee with him.

In thesis committees, graduate students present their work up to that point to a small group of professors, along with a brief text they write explaining why they do what they do.

The texts are often overly serious, theoretical explanations of things the paintings are claiming to achieve. They would be among the world’s great cultural achievements if they actually accomplished what is said in the text: abstractions that upturn patriarchy, sloppy figuration that solves climate change, and so forth. Other times, the texts are astounding confessional autobiographies that link obscure personal details with the subject matter of the work; or they describe a traumatic event, which makes a critique of anything in the work impossible, lest you belittle the artist’s personal experience.

We sit in a room staring down at the text, then up at the artwork. It can be hard to know where to begin—not because the students are hopeless or pathetic, but because, as their papers demonstrate, it is incredibly difficult to talk about art. It’s much harder for the students than it is for the professors. We have the luxuries of experience and critical distance from the work, but it still isn’t easy.

And then Reafsnyder says, “So, how do you know when a painting is finished?” Or, “If one of these paintings is the most successful for you, how do you know it?” Or, “What do you think these paintings are doing well?”

If you’ve never painted seriously, questions like these might be a little puzzling. I think painting, especially when we think in terms of paintings by “masters,” is imagined to be a thing where, if you’re good enough, you decide before you start what a painting will be and produce it. People assume that great painters can make whatever their brilliant minds determine, a priori, will be a masterpiece. But painting, like writing, is something that shows its makers what they think as the process unfolds. You can’t hold all of the details of a painting in your mind before you begin, any more than you can hold all the details of novel. You try to contain the whole thing in your mind, but there are always limits to what the artist can manage. Fatigue, distraction, a limited number of new ideas, self-consciousness, lunchtime. All these things can and do impede the perfect execution of a painter’s aspirations.

Reafsnyder seems to know this, and he engages the conversation around a painting in practical terms. Why did you do what you did? How do you know it’s good? Why do you like that relationship/color/shape? How did you get there? Is it satisfactory to you? What would improve it? What do these things mean in relation to other paintings?

His practical questions inevitably give way to meaning, and eventually history. We judge paintings, good or bad, in terms of the other paintings we’ve seen. Paintings that are understood to be “great” establish some of the criteria for the great paintings that follow. It’s impossible to judge a painting except in relation to other paintings, and that can place an incredible weight on an artist. Reafsnyder’s approach in a critique is similar to his approach to painting. His work asserts that while the pressures of history are inevitable, if we focus on the material right in front of us and what we can do with it, and are honest about what our manipulations produce, we can forget about history for a moment and be present with the painting. Assessing what the manipulations produce will always require a comparison, conscious or unconscious, to prior forms in painting, culture, or nature—there’s never a perfect escape from meaning, and Reafsnyder wouldn’t want there to be. I like to believe that when he’s looking at a student’s painting, and when he’s making his own work, he suspends his preconceptions about what each moment in a painting might imply. A genuine curiosity about what’s possible seems to unburden his approach from proscriptive assertions about what a mode of painting means.

How else could the guy have gotten to making gestural abstraction that feels like the joy of catching up to the ice cream truck just as it starts to drive away—when the history of that kind of painting feels more like Sigmund Freud and the atom bomb?

When I first saw the works for this show in person, I had been looking at JPEGs of them for a while. So when I was in New York before this show, Michael asked me to go see them at the gallery. I expected to be surprised by their scale.

That’s practically inevitable when you go from seeing photos to seeing the real thing. I had a sense that the color would have a greater range of warm and cool in person, and that was certainly the case. If you’re seeing his paintings in reproduction, know that there’s a subtlety in the actual works, particularly in the ones that are heavy on blue, that a photographic image just isn’t capable of capturing. Pigments do something that reproductions in either the red/green/blue of the screen or the cyan/yellow/magenta/black of printed matter cannot. There are combinations of saturation and luminosity that are beyond the gamut of the current technology, and there’s a sensitivity to hue in these paintings that makes your eye feel the sensation of the color as much as the undulating surface of the material lets your eye sense the facture of the paint.

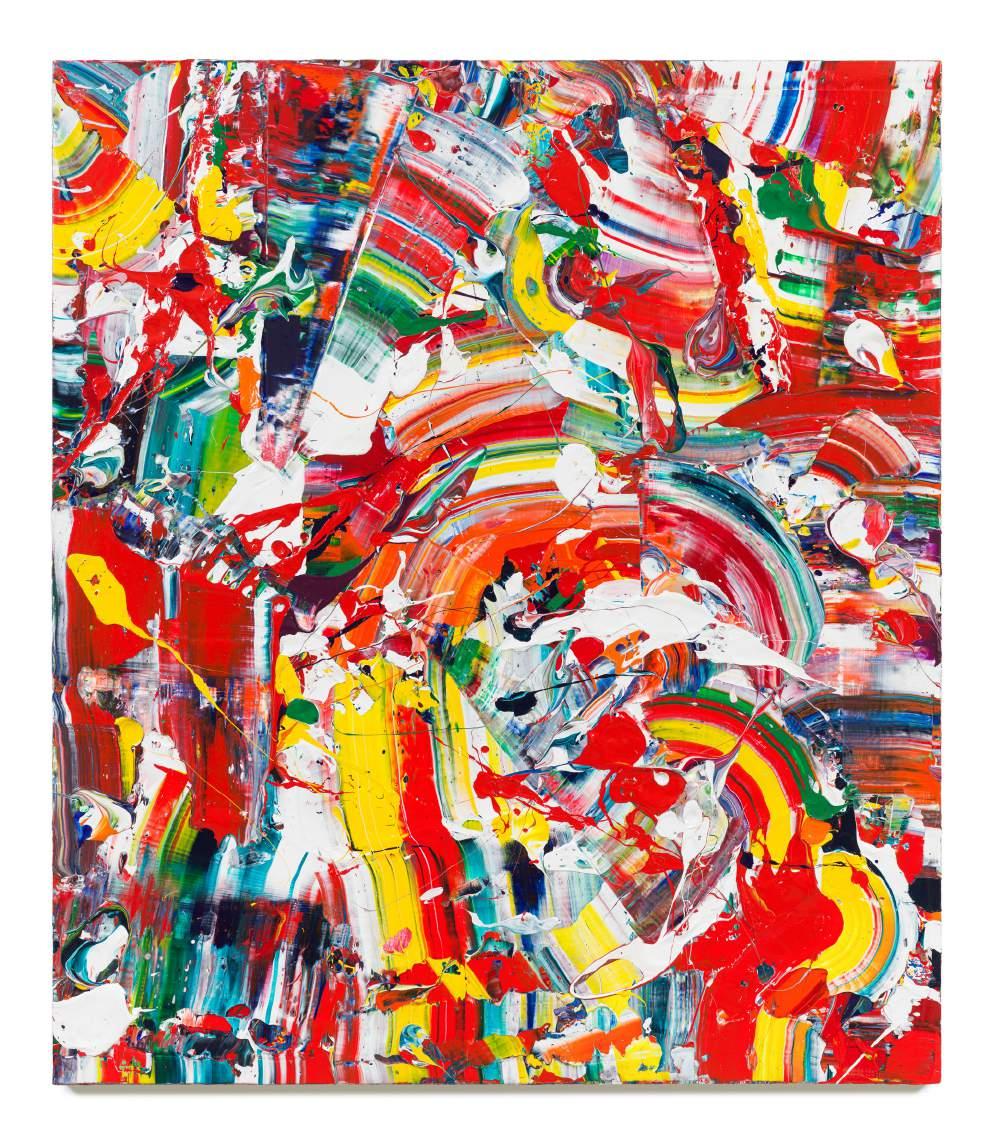

There was something else I had missed in the JPEGs. I didn’t notice it at first, then I caught it in one of the paintings. As I looked further, I saw it was in almost all of them. There appears to be a subtle stripe, running parallel to one edge of each canvas. It isn’t painted with a separate overlay of color or by running a brush or palette knife over the surface of the painting. It appears to be made by taking a 2-by-4 board, setting it into the thick wet paint, pressing it down and lifting it back off. The paint that remains shows a mushy ghost of the board’s outline. The paint within the stripe is blended and smudged and puckered.

This gloopy stripe, so redolent of history, genuinely took me off guard. That 2-by4 mark is doing double-duty. On the one hand, it’s an homage to Pollock’s Blue Poles (1952), a painting Pollock finished by making a series of large blue lines across the surface by soaking a board in paint and dropping it on the surface of his canvas as it lay on the floor. Of all the histories to invoke, we get Jack the Dripper, the grandaddy of macho painterly pathos. On top of that, the wet smudge of Reafsnyder’s 2-by-4, parallel to the edge of the painting, recalls Gerhard Richter’s squeegee, dragging the wet paint across the surface, making his signature smears—themselves a rebuke to the overwrought feelings of American painterly abstraction.

It could look as if Reafsnyder is an innocent—or at least pretending to be one in order to get to a place where history can’t infect him. He does play around in the paint the way a toddler, blissfully unaware of bacteria, makes mud pies. The stripe he makes with the board, though, is a nod to the inevitability of historical readings.

He knows as well as anyone what the stakes are, and who was here before. His deployment of this gesture is extremely particular. It functions as a brand on these pictures and ties them together as a series. A move that is all drama when done by Pollock and that functions as a kind of resistance to the egocentrism of American abstraction when done by Richter, becomes sly, knowing, and tongue-in-cheek when Reafsnyder does it.

If you stare long enough at one of these paintings, you might see a face in the swirls of paint. I wonder if me seeing Pollock and Richter is part of the same effect. It’s subtle enough that I can honestly wonder if the historical reference I saw was put there on purpose. Reafsnyder’s teaching approach is instructive here. All the questions about how a decision is made and what is good in a painting are staking out a kind of system for understanding what a painting is aiming to do. I would venture that in Reafsnyder’s work, the aim is something like this: Paint is a material. It is organized in a painting by play and discovery.

That organizing will inevitably produce arrangements of paint that generate meaning, be they ghostly faces or histories or sense-tingling fields of color. The sensations have affect and are not neutral. The histories aren’t either, but Reafsnyder won’t let them be albatrosses. He comes to them with other things—his proclivities and tastes, his peculiar banks of knowledge, the limits of his particular physical self—that let those histories go off on tangents, turn into jokes or open up on more possibilities for play.

1. Clement Greenberg, “Towards a Newer Laocoön,” Art in Theory 1900-1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, eds. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishers, 1992): 554-60.

26

Born in Orange, CA in 1969

Lives and works in Orange, CA

1996

MFA, Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, CA

1992

BA, Chapman University, Orange, CA

2024

Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

2023

Weber Fine Art, Greenwich, CT

2022

Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

2020

Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

2017

Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY

2016

“In Bloom,” R.B. Stevenson Gallery, La Jolla, CA

2015

Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY

2014

“Sunday Best,” Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Los Angeles, CA

2013 “We Ate The House,” Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY

2012

“Gleam,” R.B. Stevenson Gallery, La Jolla, CA

2011

“Feast,” Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY

“Delight,” Marty Walker Gallery, Dallas,TX

2010

“Sweetness,” Rebecca Ibel Gallery, Columbus, OH

“Put it There: New Paintings and Ceramics,” Western Project, Culver City, CA

2009

“Undone,” R.B. Stevenson Gallery, La Jolla, CA

Western Project, Culver City, CA

2007

“Aqualala,” Western Project, Culver City, CA

“Fresh,” W.C.C.A., Singapore

“Whirl,” R.B. Stevenson Gallery, La Jolla, CA

2005

“More: Paintings and Sculpture from 2002-2005” (curated by Libby Lumpkin), Las Vegas Art Museum, Las Vegas, NV

2004

“Yum-Yum,” Uplands Gallery, Melbourne, Australia

2003

“Paintings,” Mark Moore Gallery, Culver City, CA

2002

“Paintings,” Galería Marta Cervera, Madrid, Spain

“Paintings,” Finesilver, San Antonio,TX

53

2001

“Paintings,” Mark Moore Gallery, Culver City, CA “Present/Future,” Artissima, Turin, Italy

1999

“Paintings,” Mark Moore Gallery, Culver City, CA “Monotypes/Paintings,” Cheryl Pelavin Fine Art, New York, NY

1997

“Paintings,” Blum & Poe, Santa Monica, CA

1996

“Paintings,” ArtCenter College of Design, Pasadena, CA

2023

“Two of Us: Dion Johnson and Michael Reafsnyder,” Contemporary Art Matters, Columbus, OH

2022

“Summer Drift,” Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

2021

“Flying Colors,” Contemporary Art Matters, Columbus, OH

“Return of the Dragons,” Blossom Market, Los Angeles, CA

2020

“Do You Think it Needs a Cloud?,” Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

“Little Gems,” Telluride Fine Art,Telluride, CA

2019

“Combo Platter: Collaborative Works by Michael Reafsnyder and David Kiddie,” Harris Art Gallery, University of La Verne, La Verne, CA

2018

“Abstract Thinking,” R.B. Stevenson Gallery, La Jolla, CA

“Michael Reafsnyder & Patrick Wilson,” Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

“Belief in Giants,” Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

2017

“Non-Objective” (curated by James Hayward), Telluride Fine Art, Telluride, CO

“Painters Room,” R.B. Stevenson Gallery, La Jolla, CA

2015

“Works of Paper II,” ACME., Los Angeles, CA

“Recent Acquisitions,” Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Las Vegas, NV

“Paths and Edges,” Guggenheim Gallery, Chapman University, Orange, CA

2014

“Floor Flowers,” East and Peggy Phelps Gallery, Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA

2012

“Into the Light,” Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Las Vegas, NV

2011

“Los Angeles Museum of Ceramic Art,” ACME., Los Angeles, CA

“Summer Selections,” Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY

2010

“Forever Now: A Group Exhibition,” East and Peggy Phelps Gallery, Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA

“Just Enough,” R.B. Stevenson Gallery, La Jolla, CA

“Keramik,” Pacific Design Center, Los Angeles, CA

2009

“Good Ship Lollipop,” CTRL Gallery, Houston, TX

“Selected Works from Pilliod Records,” Morgan Lehman Gallery, New York, NY

“Way Out West,” Donna Beam Art Gallery, Laguna Beach, CA

“Collecting California,” Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, CA

“The First Six Years,” Western Project, Culver City, CA

“Well Tempered,” R.B. Stevenson Gallery, La Jolla, CA

“Electric Mud” (curated by David Pagel), Blaffer Gallery, University of Houston, Houston,TX

2008

“Like Lifelike” (curated by Brad Spence), Sweeney Art Gallery, University of California, Riverside, Riverside, CA

“iCandy: Current Abstraction in Southern California,” Cypress College Art Gallery, Cypress, CA

“Splash,” Rebecca Ibel Gallery, Columbus, OH

“Luscious Abstraction,” Frank M. Doyle Arts Pavilion, Orange Coast College, Costa Mesa, CA

“Black Dragon Society,” Black Dragon Society, Los Angeles, CA

2007

“Summer Selections,” Rebecca Ibel Gallery, Columbus, OH

“Abstract,” R.B. Stevenson Gallery, La Jolla, CA

2006

“Too Many Tear Drops,” David Reed Studio, New York, NY

“A Little So Cal Abstraction,” Mandarin Gallery, Los Angeles, CA “Discovery,” West Coast Contemporary Art, Singapore

2005

“Step Into Liquid” (curated by Dave Hickey), Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles, CA

“In Bloom,” Mark Moore Gallery, Culver City, CA Black Dragon Society, Los Angeles, CA

2004

“Fresh Paint,” Gallery Eugene Lendl, Graz, Austria

“Painting and Sculpture,” Mark Moore Gallery, Culver City, CA

“Funny Business: Humor in Art from the Permanent Collection,” Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, CA

“The O Scene,” Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, CA

“Now and Then Some,” Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA

2003

“LA TAP,” Uplands Gallery, Melbourne, Australia

“Not the Usual Suspects” (curated by James Hayward), Manny Silverman Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

“Pfat and Sassy,” Charlotte Jackson Fine Art, Santa Fe, NM

“Extreme Paint,” Peter Blake Gallery, Laguna Beach, CA

55

2002

“Five Times Four,” Modernism, San Francisco, CA

“Trade Show,” Guggenheim Gallery, Chapman University, Orange, CA

“New in Town” (curated by Bruce Guenther), Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR

“Western States,” Mark Moore Gallery, Culver City, CA

2001

“Cal’s Art, Sampling California Painting,” University of North Texas, Denton, TX

“One Minute of Your Time: A Brief Survey of Southern California Art from 1835 to 2001” (curated by Tyler Stallings), Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, CA

“The Stuff Dreams are Made From,” Art Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany

2000

“New Work: Abstract Painting,” Todd Hosfelt Gallery, San Francisco, CA

“New American Paintings 15” (curated by David Pagel), The Jones Center for Contemporary Art, Austin, TX “Paint, American Style,” Mark Moore Gallery, Culver City, CA

“Radar Love (with Gajin Fujita, Andrea Bowers and Linda Stark),” Galleria Marabini, Bologna, Italy

1999

“Under 500: Intimate Abstract Paintings,” Black Dragon Society, Los Angeles, CA

“LA/New York Abstract,” Cheryl Pelavin Fine Art, New York, NY

1996

“Risk,” The Loft, Laguna Beach, CA

1995

“Gander Mountain High, Ride ‘Um Hunter” (curated by Daniel Mendel-Black), Pasadena, CA

Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus, OH

Creative Artists Agency, Beverly Hills, CA

Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

Laguna Art Museum, Laguna, CA

Las Vegas Art Museum, Las Vegas, NV

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA

Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, San Diego, CA

North Dakota Museum of Art, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND

Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, CA

Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

28 March– 11 May 2024

Miles McEnery Gallery

525 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051

www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2024 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved

Essay © 2024 Julian Hoeber

Photo credit:

p. 10: © Pollock-Krasner Foundation. ARS/Copyright Agency

p. 11: © Gerhard Richter 2024 (0027)

Publications and Archival Associate Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Photography by Robert Wedemeyer, Los Angeles, CA

Catalogue layout by Spevack Loeb, New York, NY

ISBN: 979-8-3507-2811-8

Cover: Sherbert Way, (detail), 2023.