Biophilic Design:

of Health Impacts on Cities

Cover image source: https://www.photographytalk.com/photography-articles/6524-how-to-use-color-to-improve-your-photos

Summary

The cities are increasingly adopting biophilic design as a solution to address the issues of growing health and well-being. Given our innate association with nature for a long time, biophilic elements and processes, if integrated well into our built environment, have the potential to contribute to health and well-being. We argue that biophilic design induces benefits of wellbeing through its rejuvenating and therapeutic effects. We also argue that ecological services of natural infrastructures are crucial for creating a sustainable and healthier habitat. We conclude that integrated and accessible biophilic elements on diverse scales in the built environment are beneficial for human health and well-being.

Biophilia and Biophilic Design

Human beings, as part of the living ecosystem, evolved over millennia through interaction with the natural environment. Humans have developed a diverse set of innate inclinations toward nature and natural processes, known as biophilia. The symbiotic relationship with nature is crucial for human health and wellbeing. 1 The application of biophilia for the design of human habitats, including buildings and cities, is known as 'biophilic design'. Consequently, every sphere of human invention prior to the industrial revolution, including tools, buildings, and cities, was guided by biophilia. Human-nature co-existed in a harmonious relationship promoting the health and wellbeing of each other.2

Nevertheless, human pursuits of urbanization and associated technological advancements in the few centuries have conquered and exploited natural ecosystems. Technology-driven cities have isolated people from natural systems and processes, resulting in physical and emotional distress. The people started suffering from nature deficit disorder. 3 The human

biological systems have yet to adapt to technologically modified conditions devoid of nature. The destiny of human beings is trapped in the dilemma of their own construction.4

In the last few decades, there has been increasing recognition of the value of maintaining a built-nature balance in cities to address health and wellbeing concerns. The key players in the field of urban planning and development are beginning to explore alternate models of development with nature as a central piece. Biophilic designs in buildings and cities involve the direct, indirect, and symbolic elements and characteristics of nature, including but not limited to natural lighting and ventilation and natural elements. Albeit in the early stages, research show the positive impact of biophilic designs in restoring and strengthening the connection between humans and nature to solve the problems of sustainability, resilience, health, and wellbeing.

Design for Health

As Colomina and Wigley argue in their book ‘Are We Human - Notes on the Archaeology of Design’, humans design, and design, in turn, reshapes humans. Human beings today are like spiders, trapped in the environment they have created, unable to extricate themselves.6 The environments we design shape our existence and affect our physical and mental health.

In modern times, the impact of the living environment on human health began with the recognition of tuberculosis. Modern medicine has identified the causes of tuberculosis as lack of exercise, sedentary indoor living, poor ventilation, lack of light and depression among others. 7 The state of life of a new generation of young people who stay indoors, have fewer opportunities to explore nature, are held hostage by mechanized buildings, and electronics. Disconnected from nature, they suffer from "nature deficit disorder." A sedentary life has become the modern man's destiny.8

Biophilic design is based on the biophilic nature of

human beings, with a deep understanding of the impact of the natural environment on health, to reorganize and develop contemporary design practice. In the field of architecture, modern architects strengthen people's experience of nature through direct and indirect means, such as introducing natural elements such as sunlight, light and ventilation into the interior, and installing plants and sports facilities on the roof terrace to restore and strengthen the intimate connection between humans and the natural environment. Architecture is no longer a vessel to hold the body, but a means to provide health and promote human well-being and happiness.9

In the field of urban design, a biophilic city that is centered on nature and seeks opportunities for restoration through nature-based solutions that creatively integrate nature into urban infrastructure as much as possible.10 A biophilic urban environment helps residents communicate, generate and share information, and it is a platform for building self-awareness and group identity.11 Residents care about nature, improve

mental health and quality of life, and work for a healthy natural environment, while enhancing social cohesion and fostering a wider network of social interactions.

The future building is above all a health machine, a form of healing.

12 The future city is a healthy city that cares about a greener, more active and healthier lifestyle, a city of nature that is interested in human well-being and happiness.

6

7 Ibid., 110.

8 Timothy Beatley, 2010, Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning, 1st edn, (Island Press, Washington, DC.), 2.

9 Beatriz Colomina, & Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on the Archaeology of Design, (Lars Müller Publishers), 112.

10 Timothy Beatley, 2010, Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning, 1st edn, (Island Press, Washington, DC.), 46.

11 Beatriz Colomina, & Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on the Archaeology of Design, (Lars Müller Publishers), 65.

12

Biophilic Design: Enhancing Human Health and Urban Resilience

We argue that biophilic design contributes to human health and wellbeing through two intricately linked pathways. First, biophilic design induces therapeutic and rejuvenating effects, resulting in a less stressful life and faster recovery from illnesses. Secondly, the ecosystem services of natural infrastructures, such as evapotranspiration and canopy cover, contribute to reducing urban heat island effects and improving air quality in urban environments.

Biophilia and Biophilic Design: Nurturing Health and Sustainability in Urban Environments

The key players in the field of biophilia and biophilic design are Edward O. Wilson, Stephen Kellert, and Timothy Beatley. Wilson is a renowned biologist and professor in the field of evolutionary biology and ecology at Harvard University. Wilson synthesized the term "biophilia," referring to the close inclination of

humans towards nature, in the early 1980s.13 Kellert is a Professor of Social Ecology and Senior Research Scholar at the Yale University School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Whereas, Beatly is a Professor of Sustainable Communities at the University of Virginia and founder of the Biophilic Cities network.

Stephen and Timothy expounded biophilia in the field of architectural designs and cities respectively .For the selection of primary sources, we reviewed their publications to select those that are recent and relevant to our research field and arguments.

We selected Kellert’s ‘Nature by Design: Practice of Biophilic Design’ to understand the concept of biophilia and the importance of biophilic design in human health and wellbeing through the lens of the human evolutionary process. He systematically explores specific strategies for incorporating three basic elements of biophilia in buildings. First, direct experience of nature, involving direct contact with natural features including light, air, water, animals and plants; Second, indirect experience of nature, involving the shape and form of color materials, the bionic representation of nature and so on; third, the experience of space and

place, focuses on the ecological context of the setting of space and the context of how people manage and organize their spatial environment.14

In the field of biophilic design and human health, buildings are the core area of intervention as humans today spend 90% of their daily lives indoors. To understand the theoretical and scientific underpinnings of biophilic designs at a building level, we have primarily referred to ‘Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life’ by Stephen Kellert. He proposes principles and strategies for integrating nature consisting of natural light, views of nature, natural materials and plants in the building spaces. 15

13

Scaling up, biophilic design has to be adopted in an integrated and holistic manner across a range of scales in cities. Beatley’s ‘Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning’ explores modern people's disconnect from nature, concerns about losing interest in preserving or restoring nature, and a new vision for biophilic cities, calling for community engagement, integrating nature into urban infrastructure, and buildings of relevant institutions and education systems. He discussed strategies and methods of biophilic design in urban design from four basic scales of region, city, community and architecture.16

The key criterion for the selection of the secondary sources is relevance to our arguments, the prominence of authors and journals, sample sizes, and study periods.

Given the two- dimensional nature of arguments in our research, we have selected three journals for each argument.

Given humans' innate inclination towards nature, people are naturally driven to expose themselves or interact with nature directly or indirectly. Natural elements in cities have the potential to resolve issues of physical and mental health by fostering active lifestyles. Parks and natural elements in buildings and cities promote friendships and social relationships, providing avenues

for more physical activities. People, including children, living in the vicinity of parks are found to engage more in physical activities such as walking and playing

compared to neighborhoods with limited access to parks, resulting in lower incidences of chronic lifestylerelated diseases such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes.17

Similarly, walkable streets with good tree canopy cover encourage people to walk and ride while commuting to work, contributing to good physical and mental health. Further, exposure and interaction with nature lead to better cognitive functioning, psychological wellbeing and recovery. Human physiological systems are triggered to release hormones for good wellbeing when in contact with nature. The psychological systems also respond positively to the natural environment. The research shows that greater access to nature and green views leads to better cognitive functioning, more proactive patterns of life functioning and more self-discipline. 18 Amongst myriad of nature induced benefits, we are specifically arguing on the therapeutic and rejuvenating effects of biophilic design on mental wellbeing.

We selected research by Ulrich in 1984 on the effects of the view of nature through hospital room windows on the recovery of patients who underwent surgery, as it is a pioneering study in the therapeutic effects of nature. It found for the first time that exposure to nature enhances immune function and supports the body's natural healing process to promote faster recovery.19

The second article, 'Moments, not minutes: The naturewellbeing relationship,' examines the importance of connecting with nature and engaging in five factors of physical health to our sense of well-being as a way to predict and explain mental health and wellbeing. 20 The article ‘Does spending time outdoors reduce stress?’ uses different types of outdoor exposure studies, including heart rate, blood pressure and selfreported measurements to prove that being in an outdoor environment, especially in an environment

with green space, will reduce the experience of stress and ultimately improve it. The second argument is that the ecosystem services of nature contribute towards a healthier and sustainable living environment. The natural infrastructure in cities includes street trees, remnant vegetation, parks, gardens, constructed wetlands, green roofs and walls, bioswales, and water bodies, among others. These natural elements perform diverse ecosystem functions with the potential to resolve current and emerging urban issues that have a direct bearing on human health. Plants, through the process of photosynthesis, reduce the amount of carbon dioxide and produce oxygen, in addition to providing a cooling effect through evapotranspiration. The ultraviolet rays of sunlight induce the production of vitamin D in the human body. The utilization of ecosystem functions by humans to enhance their health and wellbeing is known as ‘ecosystem services’. The natural elements have to be integrated with the built environment or located within an accessible distance, known as ‘serviceshed’, for their ecosystem functions to benefit people. For instance, trees situated in close proximity to buildings and spaces result in the cooling of habitable spaces without any side effects. Conversely, the use of conventional

air conditioning systems results in the emission of carbon dioxide and air pollutants. As opposed to the predominant practice of devising engineered and technology-driven solutions, the adoption of natural or green infrastructures for creating healthy cities through mitigation of the heat island effect, cleansing water, cleaner and cooler air, and flood risk reduction is effective and sustainable.22 Here, the contribution of the ecosystem services towards reducing the urban heat island effect and improving the air quality in urban areas is the focus of our argument.

The chapter ‘Nature as a Solution’ of the ‘Biophilic Cities for an Urban Century’ establishes a link between biophilia and the health of cities and therefore chosen to one source. It points out that ecosystem services are viewed as part of an overall strategy to create a more active community, directly impacting physical and mental health and helping to offset the "urban health penalty".23

The first article’ Regulating ecosystem services and green infrastructure: Assessment of urban heat island effect in the Municipality of Rome, Italy’ reveals the

contribution of urban heat island effects from different biophilic elements consisting of peri-urban forest, urban forest and street trees is substantial in terms of temperature reduction within their buffer zones.24

The other article ‘Modeling the provision of air quality regulation ecosystem service provided by urban green spaces using lichens as ecological indicators’ found that the density and diversity of plant species in green spaces are important along with the coverage in enhancing urban air quality.

25

Endnotes

19 Roger S. Ulrich, 1984, ‘Viewing through a window may influence recovery from surgery’, Science 224(4647), 420-421.

20 Miles Richardson, Holli-Anne Passmore, Ryan Lumber, Rory Thomas Alex Hunt Richardson, M., Passmore, H.A., Lumber, R., Thomas, R. and Hunt, A., 2021. Moments, not minutes: The nature-wellbeing relationship International Journal of Wellbeing, 11(1).

21 Michelle C. Kondo, Sara F. Jacoby and Eugenia C. South, 2018, ‘Does spending time outdoors reduce stress? A review of real-time stress response to outdoor environments’ Health & place 51, 136-150.

22 Robert McDonald and Timothy Beatly, 2020. Biophilic Cities for an Urban Century: Why Nature is Essential for the Success of Cities (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing).

23Ibid., 41-61

24 Federica Marando, Elisabetta Salvatori, Alessandro Sebastiani, Lina Fusaro and Fausto Manes, 2019, ‘Regulating ecosystem services and green infrastructure: Assessment of urban heat island effect mitigation in the municipality of Rome’, Ecological Modelling 392, 92-102.

25 Paula Matos, Joana Vieira, Bernardo Rocha, Cristina Branquinho and Pedro Pinho, 2019, ‘Modeling the provision of air-quality regulation ecosystem service provided by urban green spaces using lichens as ecological indicators’ Science of Total Environment 665, 521-530.

11

Nature's Therapy: Urban Stress Relief participants' emotional experiences during walking have found that positive emotions are an indicator of stress recovery. The improvement in mood and recovery was accompanied by a decrease in perceived stress and blood pressure, as well as a decrease in total and oxygenated hemoglobin, and a decrease in heart rate and cortisol concentration. While walking in an urban park, participants had higher levels of meditation, suggesting that they were likely to recover from stress.27

The city itself is a stressful environment. The application of biophilic elements in urban spaces, as a partial solution, encourages recreation and alleviates the psychological punishment of the city. For example, in quiet environments like parks and natural areas with less noise pollution, stress levels can be reduced. Street trees can reduce noise, and the sense of belonging formed by access to urban parks and green spaces can promote communication between people and free the mind from repressed emotions or complicated affairs.26

The researchers used four types of environmental exposure: Nature viewing, outdoor walking, outdoor exercise and gardening, and put the participants in different environments, conducted 43 studies to observe the stress response of the subjects, through seven stress outcome measures, including heart rate, blood pressure, saliva, blood, EEG and self-report, and finally found that after forest exposure, The length, depth, and quality of actual sleep were significantly improved. Studies using moving electroencephalograms to monitor

Healing Spaces: Impact of Biophilic

Design on Patient Recovery

Biophilic design integrates natural elements into the built environment and can aid in recovery from illness.

Natural light regulates circadian rhythms and promotes sleep; Natural landscapes, such as biophilic artwork and green decorations, can ease anxiety and pain levels; Houseplants improve air quality by reducing pollutants and increasing oxygen levels; Some natural materials can be used to create a cozy, warm and healing environment. Incorporating water features such as fountains and miniature aquariums in indoor Spaces can create a peaceful atmosphere, while looking at the green outside through windows can have a positive impact on the patient's recovery.28

The researchers studied 200 beds of surgical patients at a suburban hospital in Pennsylvania and obtained records of patients on the second and third floors of three floors of the hospital between 1972 and 1981.

Patients who had undergone cholecystectomy were assigned to a room where they could see the natural environment through a window or a room where the

window faced a brick wall. The results of the study showed that patients assigned to rooms with Windows facing natural views spent less time in the hospital after surgery, received fewer negative reviews in the nurses' records and took fewer analgesics.29

Cooling Canopies: Nature's Answer to Urban Heat Waves

Heat waves are major health concerns in cities and are responsible for thousands of deaths due to heat stress.5 In order to address the issue, we argue that natural infrastructures consisting of interconnected green space systems ranging from forests to parks and street trees are effective interventions in creating a cooler environment during hot summer days. Plants through the process of evapotranspiration release water which cools the air. Trees also provide shade to the buildings and outdoor spaces with their canopy.30

Our argument is substantiated by the findings of a research on the ecosystem services of natural infrastructures consisting of peri-urban forest, urban forest and street trees towards mitigation of urban heat island (UHI) effect in Rome, Italy. It found that UHI can be mitigated by natural infrastructures mainly during hot summer days. The peri-urban forest has the highest cooling potential followed by urban forest and street trees. The large peri-urban forest and the urban forest were 2.5–3.2 °C cooler than their surroundings

with cooling effects extending up to 170 meters and 100 meters respectively. With regard to the street trees, the temperature is around 1.3 °C cooler than the first 10 m buffer of built-up area, and their influence is extended up to 30m from their borders.31

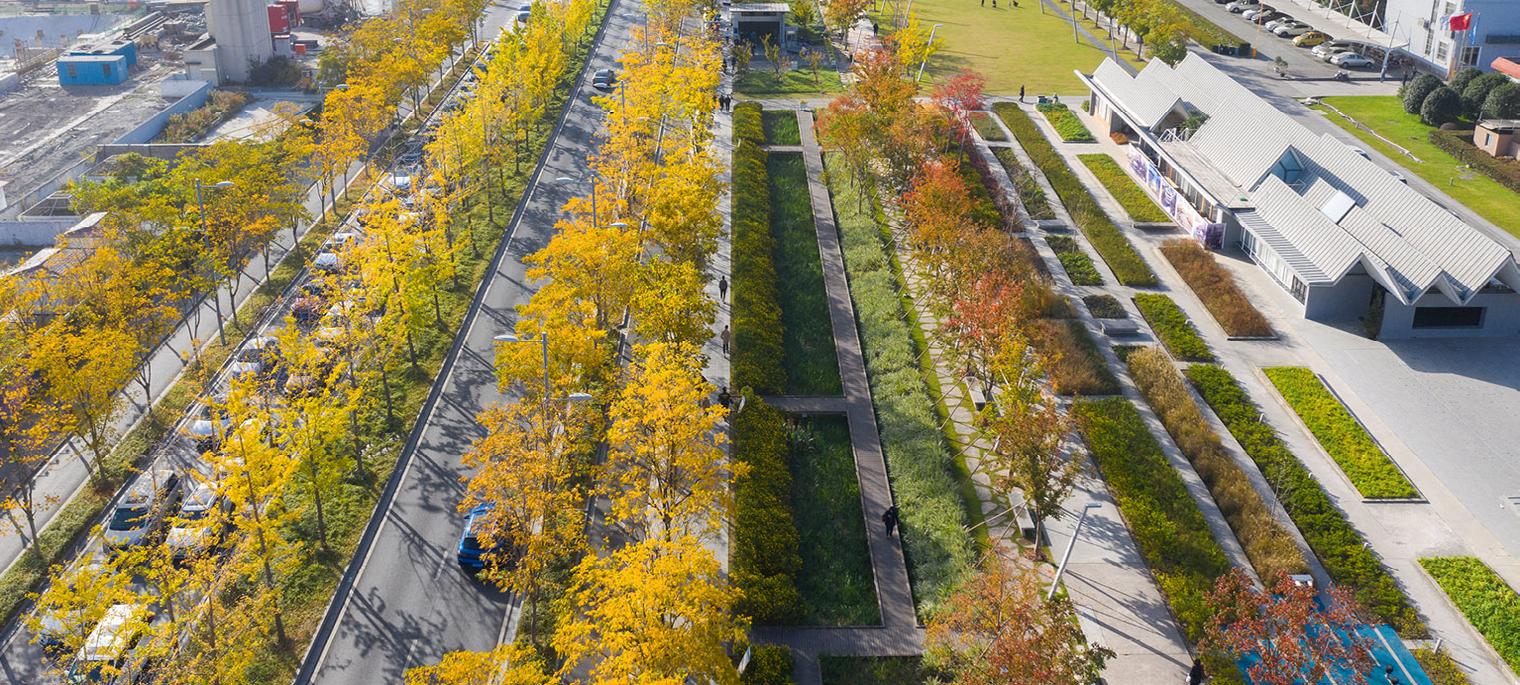

communities. (Source: https://www.gooood.cn/)

and creating healthier and

30 Robert McDonald and Timothy Beatly, 2020. Biophilic Cities for an Urban Century: Why Nature is Essential for the Success of Cities (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing).

31 Federica Marando, Elisabetta Salvatori, Alessandro Sebastiani, Lina Fusaro and Fausto Manes, 2019, ‘Regulating ecosystem services and green infrastructure: Assessment of urban heat island effect mitigation in the municipality of Rome’ Ecological Modelling 392, 92-102.

Clean Air: Harnessing Nature's Power Against Pollution

Air pollution and in particular the particulate matter (PM) is a major public health threat in cities. PM causes serious diseases including cardiovascular diseases and asthma resulting in more than three million deaths in a year.

32 In this regard, we argue that the natural infrastructures are effective in controlling air pollution although plants emit volatile organic compounds which can increase local air pollution. Leaves serve as surfaces for particular matter to settle down. The natural infrastructures also reduces air pollutants such as sulfur dioxides.33

The study findings of the ecosystem services of green spaces on air quality using lichen as an ecological indicator in Lisbon, Portugal shows that urban green spaces contribute positively towards air quality. The contribution results from an increase in the pollutant disposition surfaces by trees and decrease in the amounts of pollutants emitted near green spaces.The study shows that 10% increase in vegetation density of urban green spaces is more effective in improving air

quality than a 50% increase in green space area. It also revealed that the local green spaces contributes more than large open space systems indicating the natural elements of diverse sizes are valuable in urban areas.34

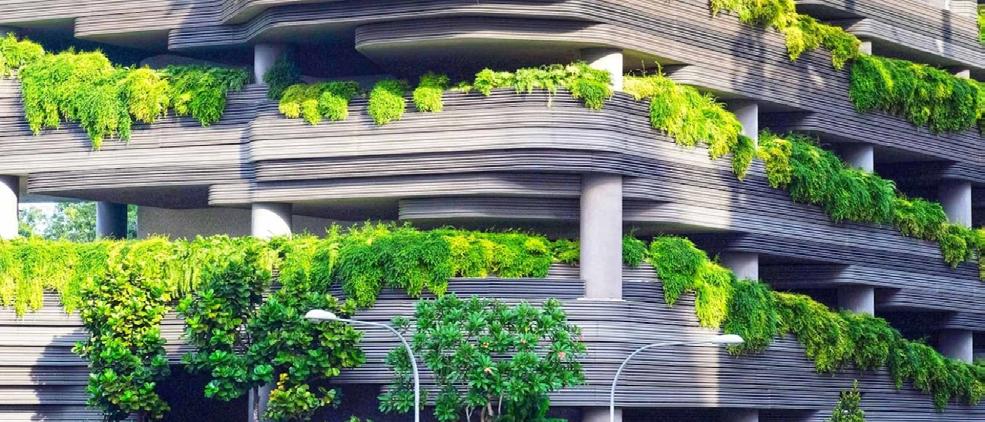

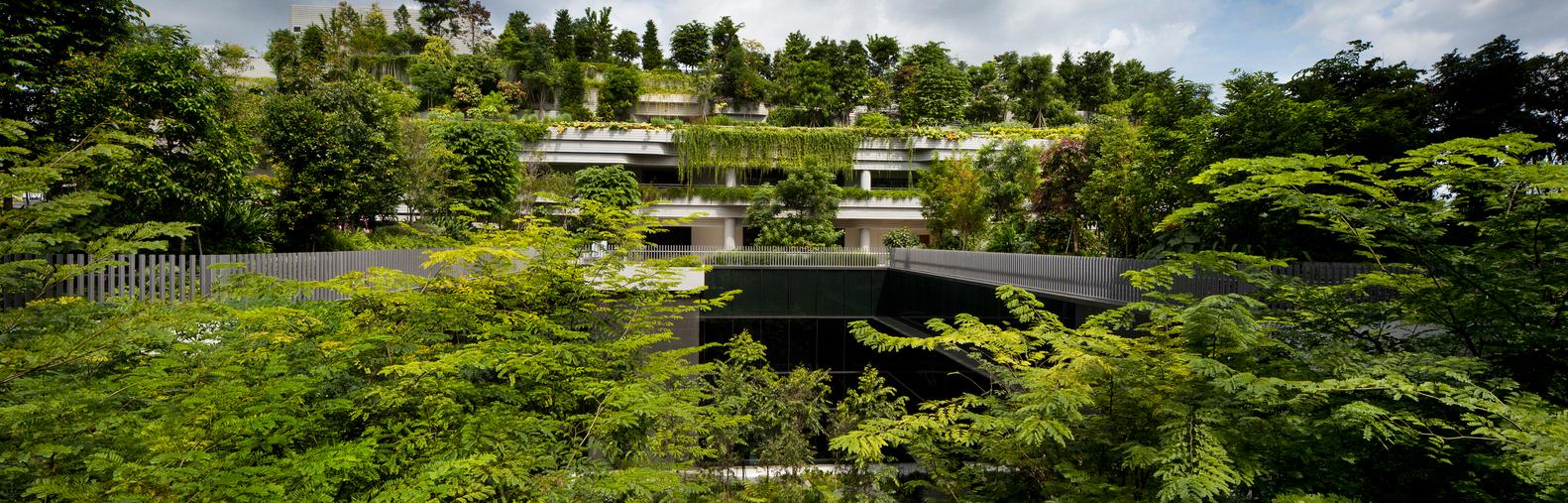

their relationship with each other, and the tree planting strategy includes biodiversity, leaves and fruit trees. (Source: https://www.archdaily.cn/cn)

32 Robert McDonald and Timothy Beatly, 2020. Biophilic Cities for an Urban Century: Why Nature is Essential for the Success of Cities (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing).

33 Timothy Beatley, 2010, Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning 1st edn, (Island Press, Washington, DC.), 83.

34 Paula Matos, Joana Vieira, Bernardo Rocha, Cristina Branquinho and Pedro Pinho, 2019, ‘Modeling the provision of air-quality regulation ecosystem service provided by urban green spaces using lichens as ecological indicators’, Science of Total Environment 665, 521-530.

Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxvxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Endnotes Endnotes:

1. Stephen R. Kellert, 2018, Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design (New Haven: Yale University Press), 18.

2. Stephen R. Kellert, 2018, Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design, (New Haven: Yale University Press), 18.

3. Timothy Beatley, 2011, Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning, 1st edn, (Washington, DC.:Island Press), 83.

4. Beatriz Colomina, & Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on the Archaeology of Design (Zurich:Lars Müller Publishers), 9.

5. Timothy Beatley, 2011, Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning, 1st edn, (Washington, DC.:Island Press).

6 Beatriz Colomina, & Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on the Archaeology of Design (Zurich:Lars Müller Publishers), 9.

7 Ibid., 110.

8 Timothy Beatley, 2011, Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning, 1st edn, (Washington, DC.:Island Press), 2.

9 Beatriz Colomina, & Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on the Archaeology of Design (Zurich:Lars Müller Publishers), 112.

10 Timothy Beatley, 2011, Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning, 1st edn, (Washington, DC.:Island Press), 46.

11 Beatriz Colomina, & Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on the Archaeology of Design (Zurich:Lars Müller Publishers), 65.

12 Ibid., 115.

13 Stephen R. Kellert, 2018, Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design (New Haven: Yale University Press), 18-22.

14 Ibid.,

15 Stephen R. Kellert, Judith H. Heerwagen and Martin L. Mador, 2008, Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life, 1st edn, (Wiley: Chichester).

16 Timothy Beatley, 2011, Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning, 1st edn, (Island Press, Washington, DC.), 83.

17 Robert McDonald and Timothy Beatly, 2020. Biophilic Cities for an Urban Century: Why Nature is Essential for the Success of Cities (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing).

18 Ibid

19 Roger S. Ulrich, 1984, ‘Viewing through a window may influence recovery from surgery’, Science 224(4647), 420-421.

20 Miles Richardson, Holli-Anne Passmore, Ryan Lumber, Rory Thomas and Alex Hunt, 2021, ‘Moments, not minutes: The nature-wellbeing relationship’, International Journal of Wellbeing 11(1).

21 Michelle C. Kondo, Sara F. Jacoby and Eugenia C. South, 2018, ‘Does spending time outdoors reduce stress? A review of real-time stress response to outdoor environments’, Health & place 51, 136-150.

22 Robert McDonald and Timothy Beatly, 2020. Biophilic Cities for an Urban Century: Why Nature is Essential for the Success of Cities (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing).

23Ibid., 41-61

24 Federica Marando, Elisabetta Salvatori, Alessandro Sebastiani, Lina Fusaro and Fausto Manes, 2019, ‘Regulating ecosystem services and green infrastructure: Assessment of urban heat island effect mitigation in the municipality of Rome’, Ecological Modelling 392, 92-102.

25 Paula Matos, Joana Vieira, Bernardo Rocha, Cristina Branquinho and Pedro Pinho, 2019, ‘Modeling the provision of air-quality regulation ecosystem service provided by urban green spaces using lichens as ecological indicators’, Science of Total Environment 665, 521-530.

26 Robert McDonald and Timothy Beatly, 2020. Biophilic Cities for an Urban Century: Why Nature is Essential for the Success of Cities (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing).

27 Michelle C. Kondo, Sara F. Jacoby and Eugenia C. South, 2018, ‘Does spending time outdoors reduce stress? A review of real-time stress response to outdoor environments’, Health & place 51, 136-150.

28 Stephen R. Kellert, 2018, Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design (New Haven: Yale University Press).

29 Roger S. Ulrich, 1984, ‘Viewing through a window may influence recovery from surgery’, Science 224(4647), 420-421.

30 Robert McDonald and Timothy Beatly, 2020. Biophilic Cities for an Urban Century: Why Nature is Essential for the Success of Cities (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing).

31 Federica Marando, Elisabetta Salvatori, Alessandro Sebastiani, Lina Fusaro and Fausto Manes, 2019, ‘Regulating ecosystem services and green infrastructure: Assessment of urban heat island effect mitigation in the municipality of Rome’, Ecological Modelling 392, 92-102.

32 Robert McDonald and Timothy Beatly, 2020. Biophilic Cities for an Urban Century: Why Nature is Essential for the Success of Cities (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing).

33 Timothy Beatley, 2011, Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning, 1st edn, (Island Press, Washington, DC.), 83.

34 Paula Matos, Joana Vieira, Bernardo Rocha, Cristina Branquinho and Pedro Pinho, 2019, ‘Modeling the provision of air-quality regulation ecosystem service provided by urban green spaces using lichens as ecological indicators’, Science of Total Environment 665, 521-530.

Beatley, Timothy. 2011. Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning. Washington, DC.: Island Press.

Kellert, S. R. 2018. Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kellert, S. R., Heerwagen, J.H, & Mador, M.L. 2011. Biophilic design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Willey & Sons.

Kondo, M.C., Jacoby, S. F., and South, E. C. 2018. 'Does spending time outdoors reduce stress? A review of real-time stress response to outdoor environments.’ Health & place 51: 136-150.

Marando, Federica, Salvatori, Elisabetta, Sebastiani, Alessandro, Fusaro, Lina and Manes, Fausto. 2019. ‘Regulating Ecosystem Services and Green Infrastructure: Assessment of Urban Heat Island Effect Mitigation in the Municipality of Rome, Italy. Ecological Modelling 392: 92-102.

Matos, Paula, Vieira, Joana, Rocha, Bernardo, Branquinho, Christina, and Pinho, Pedro. 2019. ‘Modeling the Provision of Air-Quality Regulation Ecosystem Service provided by Urban Green Spaces using Lichens as Ecological Indicators.’ Science of the Total Environment 665: 521-530.

McDonald, Robert and Beatley, Timothy. 2020. Biophilic Cities for an Urban Century: Why nature is essential for the success of cities. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Richardson, Miles, Passmore, H. A., Lumber, Ryan, Thomas, Rory, and Hunt, Alex. 2021. ‘Moments, not minutes: The nature-wellbeing relationship.’ International Journal of Wellbeing, 11(1).

Ulrich, R. S. 1984. ‘View through a window may influence recovery from surgery.’ Science 224(4647): 420421.

Figure 1 Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl, 2017, ‘Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park’, https://www.gooood.cn/2016-aslabishan-ang-mo-kio-park-by-ramboll-studio-dreiseitl.htm, accessed 5 April 2024

Figure 2 Sasaki, 2021, ‘Xuhui Runway Park’, https://www.gooood.cn/xuhui-runway-park-by-sasaki.htm

Figure 3 Chapman Taylor, 2024, ‘What are the benefits of biophilic design? ’, https://www.chapmantaylor.com/ news/q-a-what-are-the-benefits-of-biophilic-design, accessed 10 May 2024

Figure 4 Oki Hiroyuki Da Nang, 2024, ‘Naman Retreat Pure Spa’, https://architizer.com/blog/inspiration/ collections/green-rooms-photographing-biophilic-architecture/, accessed 10 May 2024

Figure 5 Stephen R. Kellert, 2018, Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design, (New Haven: Yale University Press), 132.

Figure 6 TASNEEM BAKRI, 2021, ‘What is Biophilic Design? Definition and Benefits’, https://www.alpinme. com/biophilic-design/, accessed 10 May 2024

Figure 7 Sasaki, 2021, ‘Xuhui Runway Park’, https://www.gooood.cn/xuhui-runway-park-by-sasaki.htm, accessed 2 May 2024

Figure 8 Sasaki, 2021, ‘Xuhui Runway Park’, https://www.gooood.cn/2021-asla-urban-design-award-of-honorxuhui-runway-park-sasaki.htm, accessed 2 May 2024

Figure 9 Stephen R. Kellert, 2018, Nature by Design: The Practice of Biophilic Design, (New Haven: Yale University Press), 140.

Figure 10 Sasaki, 2021, ‘Xuhui Runway Park’, https://www.gooood.cn/2021-asla-urban-design-award-ofhonor-xuhui-runway-park-sasaki.htm, accessed 2 May 2024

Figure 11 WOHA, 2017, ‘Kampung Admiralty’, https://www.archdaily.cn/cn/977644/xin-jia-po-ru-he-zai-dazao-lu-se-cheng-shi-huan-jing-zhong-yin-ling-xian-feng?ad_name=article_cn_redirect=popup, accessed 2 May 2024

Figure 12 Marthe de Ferrer, 2021, ‘Singapore: The city that learned how to blend nature with urban living’, https://www.euronews.com/green/2021/11/11/how-has-singapore-learned-to-blend-nature-with-urban-living, accessed 2 May 2024