C ONTENTS FOREWORD A FRIENDSHIP THAT TRANSCENDS TIME DEFINING A STORY THROUGH COLOUR THE WORLD Welcome to Vi V rennes! the memorial the Uncle’s hoUse WHO ELSE INHABITS THIS WORLD? NARRATIVE MEDIA LANDSCAPE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 5 7 17 21 23 31 3 39 47 81 88

... that if powerful countries would reduce their weapon arsenals, we could have peace. But if we look deeply into the weapons, we see our own minds- our own prejudices, fears and ignorance. Even if we transport all the bombs to the moon, the roots of war and the roots of bombs are still there, in our hearts and minds, and sooner or later we will make new bombs. To work for peace is to uproot war from ourselves and from the hearts of men and women. To prepare for war, to give millions of men and women the opportunity to practice killing day and night in their hearts, is to plant millions of seeds of violence, anger, frustration, and fear that will be passed on for generations to come.

We often think of peace as the absence of war ...

“ ”

— THICH NHAT HANH

De D icate D to those i call my family.

F OREWORD

Growing up I have been passed down stories by my mother, my grandparents, and greatgrandparents, of how the effects of the war ricocheted through their lives generationally. And whenever I’d listen, something deep inside always shook me as I realised that:

Their stories and lives inevitably carry on through me.

To this day it still makes me wonder: if I was not born now but then, how differently would I look at the world? And had I been the same age as any of them for a time, maybe even their friend, what would that have been like? How would I be changed, and what would I know that I don’t now? Would I be wiser for it, or stay the same? In the end, what is it that makes up my true identity, and how much does history, and my family, play into it?

There are parts of ourselves that we can’t fully comprehend, but it is our chance to try. Even as a singularity, we are a union of the past; it has taken millions of lives to bring you here where you are today, and each of them has lived, and survived, through all kinds of events just as intensely as you.

Scientifically speaking, studies surrounding intergenerational trauma have shown how traumatic experiences epigenetically influence future generations. When even in our closest ancestry we still experience all the pain that they have been through, I like to think that life has trusted us with the chance to heal the past. For us, and for them.

And while out loud it might all be simply said, it is no easy feat. Befriending the parts of ourselves that we would much rather keep numb is a difficult process. But more often than not, allowing a painful truth to come home is what opens the door to go forward.

B urning Magnolia is an attempt for me to try and understand, and hopefully inspire others to do the same.

5

A F RIENDSHIP THAT T RANSCENDS T IME

7

Burning Magnolia is a concept for an animated feature film, aimed at mature audiences ranging from young adults and above. It circles the themes of loss, trauma, and warspecifically surrounding World War II in Northern France, except the story is told through the eyes of someone coming from a generation further down the line.

Théa, our protagonist, is forced to break out from her mundane, seclusive life once her uncle, her last living relative, passes away. Left all alone, we follow her journey as she returns to her uncle’s countryside home, where painful truths of her past come to light in the form of sudden, surreal visions, as well as a bright boy called Christoff whose presence, seemingly, only she is aware of.

Together, they face these truths of their shared past, and help one another in transcending the ties of time that burdened them from letting go.

9

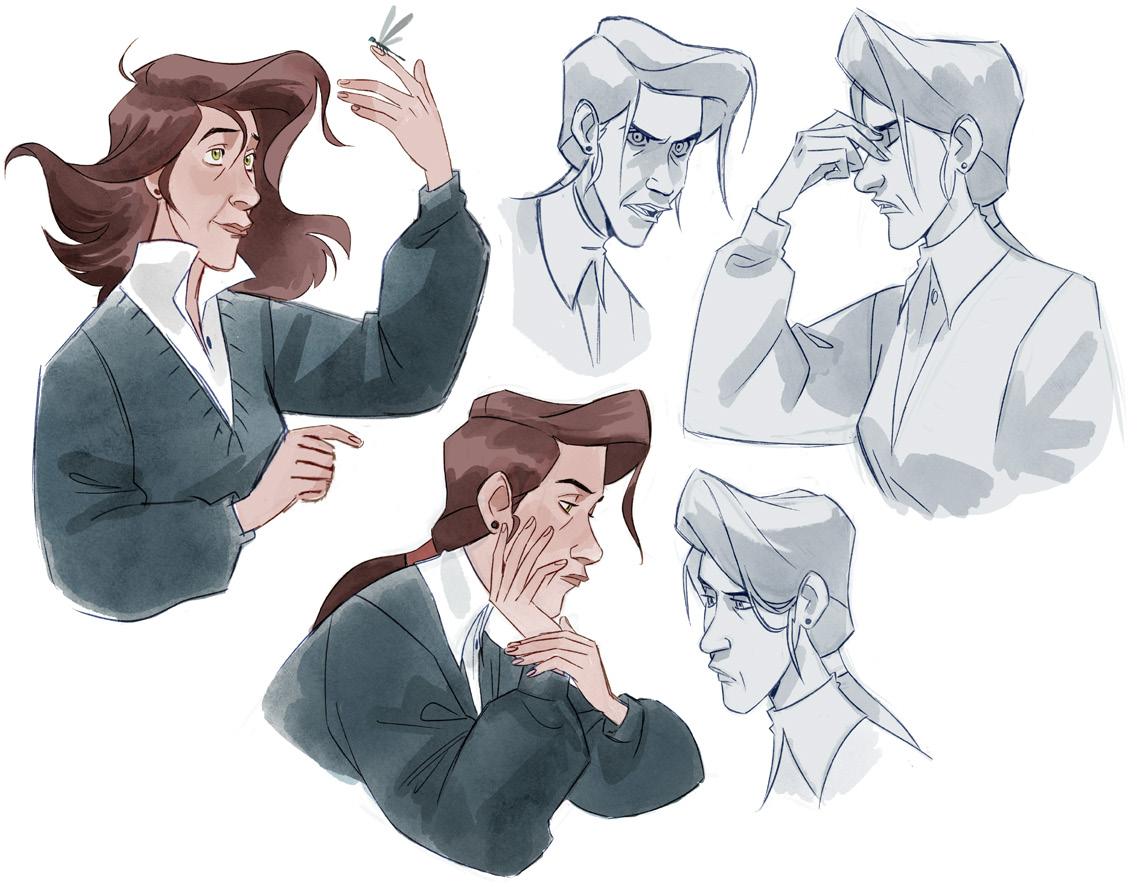

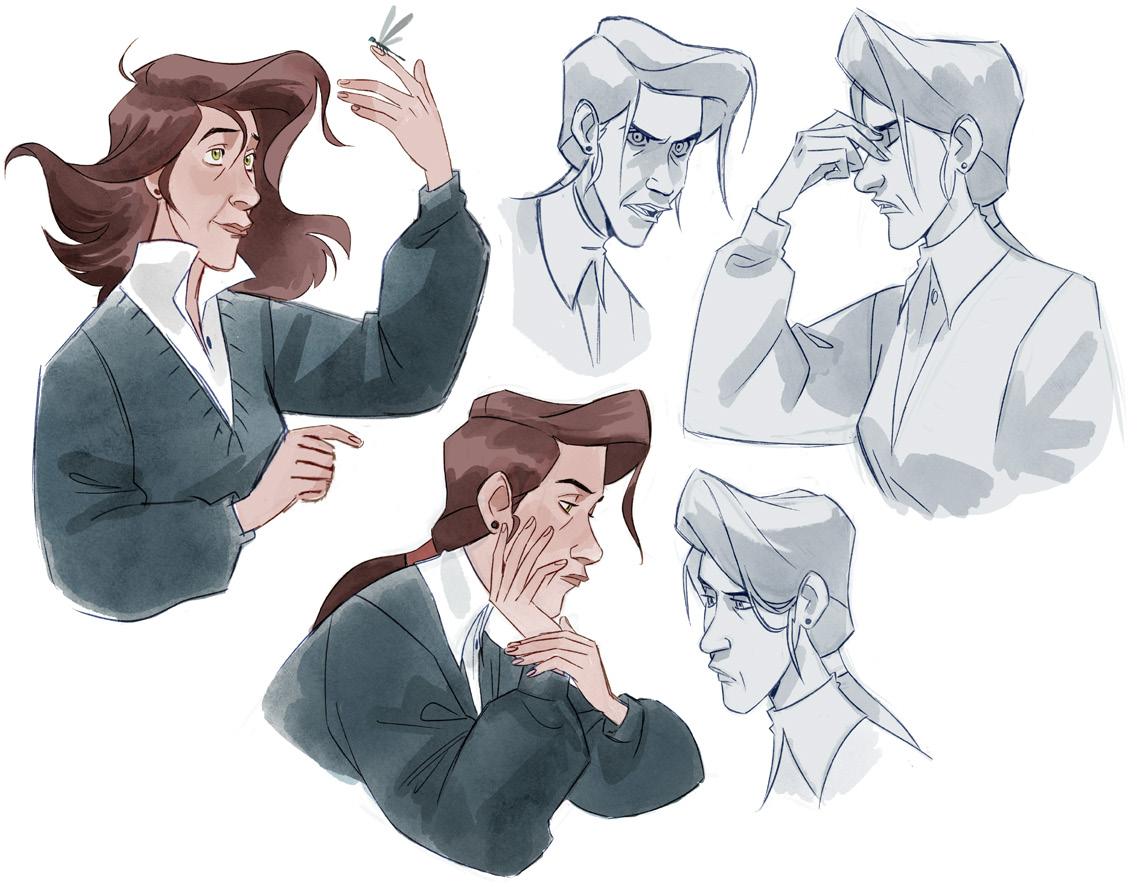

T HÉA

the lonely entomologist

Théa is a headstrong and hard-working woman who is dedicated to her craft, entomology, almost to a fault. Her fascination for bugs comes from a young age when she’d collect woodlice in jars or flies underneath dinner glasses.

I wanted her character design to strike a balance between peculiar and casual; she’s not supposed to stand out, but still retain some particular features that are unique to herself, like a pointy jaw and longer nose. Her clothing is simple and very practical. Maybe even buttoned up a little too tightly, like someone trying to keep herself contained, but still her hair is faintly disheveled to show she’s not obsessive about her appearance.

No, Théa is just someone who is subconsciously averse to connection. And what I mean by subconsciously is that her detachedness is not an act that she plays up to safeguard herself. Grief comes in many forms, and Théa’s character is grieving without being aware that she is grieving. It is simply a weight she’s become accustomed to carrying around, to the point where she can’t really see or understand why she exhibits certain behavioural patterns.

Having lost both her parents to an accident at twelve, and consequently put under the care of her grandparents until they too passed away in her early twenties, Théa finds that solitude is her way of dealing with life.

She is a very unsure person, and much like the insects she studies, she feels small and unseen.

10

Her story starts with her having a very tunneled vision, finding it easier to discard the wider world for the safety of microscopic details, but what she needs is to brave the fog filling her mind and reconcile with the loss she has suffered.

When she first arrives at her uncle’s home, her intentions are to sell and be done with it. She simply wants to return to her normal life, where the challenges she faces revolve around what she knows...

11

C HRISTOFF

Someone from the past...

Although the flurry of time can make us forget those that came before us, it does not mean that those lives were any less... well... lively than our own. With that in mind, I introduce to you: Christoff, a true representation of this phrase.

This young boy is not exactly a ghost or spectre, but more like a fragment of time, or an echo of the past, that only Théa can perceive and interact with. At the beginning she even believes him to be the childhood spirit of her deceased uncle, unable to pass on, and she isn’t technically wrong, but she isn’t right either.

As the story progresses, Christoff turns out to be Théa’s blood-related uncle who was sadly killed in the destruction of a nearby village during the war. Therefore meaning that the uncle Théa grew up knowing is someone else entirely...

12

Vibrant and boyish in every way, Christoff is as a gangly, young boy that enjoys playing with sticks, and rocks. He has many questions for the world around him that he wants answers to, and he wants those answers right now! Somewhat Peter-Pan-esque in nature and role, I wanted his shapes to reflect both the impishness of his character, but also the vulnerability of being so young. The boy comes from a wealthy middle-class family of the 1940s, with his father a military industrialist and his mother a seamstress. We can only watch as his carefree attitude is warped by the looming, terrifying encroach of war.

Towards the end, we find out about his fear of becoming meaningless and forgotten, and how essentially - even if without meaning to - Théa and everyone in her family has done so through their generational grief and numbness.

13

How can this friendship ‘ TRANSCEND ’ time?

Well, the concept of Burning Magnolia hinges on the idea that Théa is capable of connecting and looking back into the past.

So how does it work?

This is not to be confused with her having some sort of power over the passage of time, or her experiencing time-travel; these occurrences are out of her control, to the point that when it first happens to her she begins to ponder if her sanity is fully intact, or if she’s just plain hallucinating. It is more like she’s able to re-witness these moments in time as if she’d been actually present for them, there and then. It is similar to how empathy allows someone to feel what another person is experiencing.

Another factor that plays into this is that all these moments are all connected to Christoff’s presence, because he is connected to her. Like stated prior, we come to find out that he is Théa’s blood-related uncle that she never got to meet due to the tragedy of his death, but this is not revealed to her, and us, until much later in the story.

This breakage of linear time is what allows them to heal; Christoff is the one to open up Thea’s blinds, and in return she acknowledges his person - his life.

14

Théa & christoff

Early development

15

D EFINING A S TORY THROUGH C OLOUR

17

THE PRESENT

A core feature to the way this story is told visually is how the rhythm of colours indicate the shift between the past and present. Since we follow the narrative through Théa’s eyes, it is important that the colours and shapes on screen are composed in order to reflect her interiority and character development.

It begins with greyed, desaturated browns and blues, as if the images themselves were made of dust. When inside a closed space, such as a room in her uncle’s home, foreground elements are dark and encroach around her.

When outside in open spaces, such as the countryside, the world grows more hazy to symbolise her lack of grounding in a new and unknown place, but also her emotional disconnect and short-sightedness; her mind is a thick fog she’s yet to learn how to surpass.

18

& THE PAST

And so, when Christoff appears to her, and her only, it is such a surreal experience that the contrast lands on the polar opposite of the scale.

The world is brighter, crisper and bears that same uncanniness of a cold, midsummer shadow; the sky feels a little too blue, or the setting sun casts an almost fluorescent lime light.

The past is more vibrant than her present, but the truth is: neither of these are a concrete reflection of reality.

Slowly, the aim is that colours on either end of the spectrum will, through trials and tribulations, balance the other out until the ending bears more realistic hues. The mark of a fresh beginning...

19

THE W ORLD

21

welcome to V IVRENNES !

The fictional, sleepy town of Vivrennes sits silently among the hilly countryside in Normandy, a piece of it forever missing, destroyed by the Allied Bombings of Normandy in June 1944. Any building far too destroyed to be brought back was cleaned out to allow space for agriculture, while some of the ruins are left to stand between fields as a reminder.

Life in WWII France...

The setting and history of Vivrennes is modeled after Nazi-Occupied Normandy during World War II. Up until D-Day’s victory, some of the Norman, countryside towns were able to partially ‘escape’ the harsher treatment other places in France underwent. Life had to go on somehow; shops opened and markets sold whatever produce they had left. People did their best to carry out their livelihoods and survive, and thankfully had the land to live off of which cities, like Paris, did not.

Some would try to sneak out produce from the countryside into the more urban areas, but there was always the risk of interception as Nazi soldiers paraded the entrances of the villages. Stores would still have packaging in their window displays, though none of it could be actually bought as the Germans confiscated all they could. From primary goods, produced goods and all foods. Food rationing was established in the form of tickets, depending on age and occupation, though these did not guarantee you’d receive the promised quantity, only the right to stand in winding queues...

23

Why ‘Vivrennes’?

My intention with creating a fictional village rather than using an already existing one was that I wanted a setting that could symbolically connect with the war stories that have been passed down to me by family and friends, as well as places that have been a part of my own life. My hometown, albeit not in France but in Italy, has a park that was created over an old artillery dump.

It stretches beside the road connecting my house to my grandmother’s, and growing up it left a huge impression on me. It weighed and unsettled me, and now I think I can understand why. It was as if time had stopped running at some point when you entered, no matter how many times I passed through it, or even if I were walking safely together with my mum or grandparents.

24

k ey e vents for context

1931

Théa’s uncle is born.

1932

Christoff is born.

6th JUNE 1944

D-Day Landings.

6th JUNE - 19th JULY,

5-11th SEPT 1944

Bombings of Normandy.

1969

Théa is born!

1st SEPT 1939

Germany invades Poland.

10th MAY 1940

Germany invades

Northern France.

14th JUNE 1940

Paris falls to Nazis.

8th MAY 1945

Germany surrenders. WWII officially ends September 2nd when formal surrender documents are signed.

38 years later... and here we are!

The decade leading into the 2000s is when this story is set.

25

The town’s design...

As established, Théa experiences two different time periods, requiring different visual cues to signal the shift. Aside from colour, the layout and structure of the buildings of Vivrennes is equally important.

The town is supposed to look weathered, shaken up by the bombing it endured, as walls that were once straight now skew this way and that, fighting gravity.

In Théa’s present, the apartments left over from before the war are tightly knit together and leaning on to one another for support, meanwhile the newer or fully restored structures stand upright. Facades have been rebuilt; storefronts are mostly, if not entirely, different compared to their predecessors; flashing signs and large, metal placards advertise their goods; cables run up and down the rooves...

26

Conversely, in Christoff’s present — therefore meaning the past — the buildings that appeared skewed to Théa are well aligned in their rows. Medieval houses are bundled between newer stone and brick apartments, their old walls from oncea-upon-a-time still showing their earthy age; the pathways are rockier, comprising of either dirt or cobblestone; the trees lining the streets are scattered

mostly at random, likely left over from when the land was simply countryside; and the roads are just flattened ground and gravel.

The past is not in any way meant to appear like a more ‘perfect’ version of the present, it only serves to emphasise Vivrennes’ adaptation to time as a consequence to what it has been through.

27

Comparison of town buildings during the present, on the left page, and the past, on this page.

SKETCH OF VIVRENNES STREET prior to WWII.

SKETCH OF VIVRENNES STREET prior to WWII.

Further town Explorations

My aim was for the town to feel as real as possible. As if you could really imagine yourself strolling down the street, sensing the warmth of the sun change on your skin as you shift between the cool, stony shadows of trees and stacked apartments...

29

More examples of town buildings during the present on the left, and past, on the right.

THE M EMORIAL

The Magnolia Tree

Up on the small hill overlooking the town, a grouping of some dozen magnolia grandiflora once spread their evergreen branches towards the sky. This was called Magnolia Grove.

Now, however, only one remains, having miraculously survived the onslaught of bombs while the rest burned. It keeps reaching higher than ever before, serving as a memorial next to the Tourism Centre and Municipal Library.

32

Magnolia trees are a grand symbol of the town. At first glance their flowers might appear as delicate as the next tree blossom, but the truth is they’re extremely resistant. Their petals are hardy, and its leaves are thick-skinned.

Considered one of the first flowering plants to have evolved on Earth, they symbolise endurance and perseverance, much like the town it decorated.

Tourism Centre & Municipal Library

These buildings were built during the reconstruction of Vivrennes, with the spot being chosen both for its panoramic view over the town, but also its symbolic importance. The library also functions as an archive for old documents, and together with the Tourism Centre offers guided group-tours to those who prefer to learn more through a scenic walk.

33

THE U NCLE’S H OUSE

34

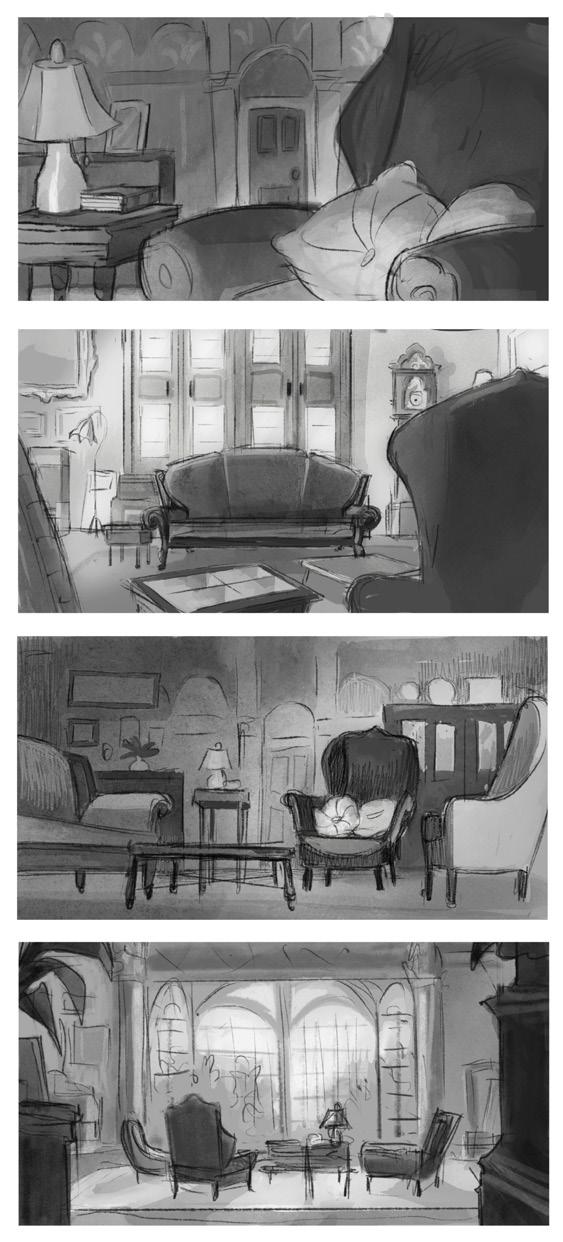

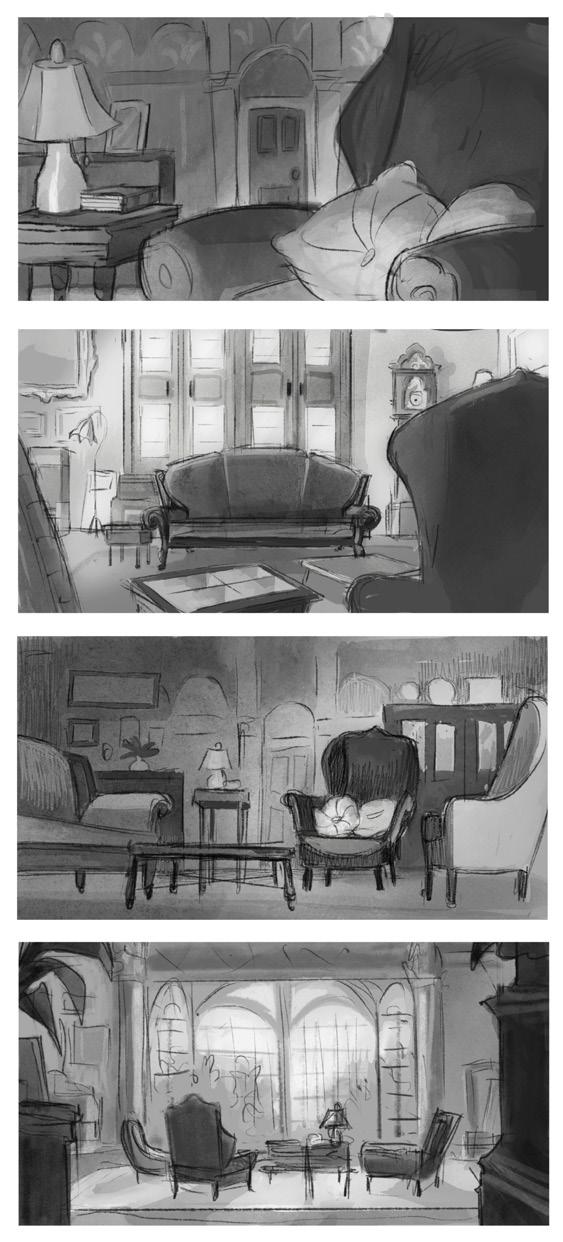

Exploratory sketches

It is generally what you’d expect the house of a deceased loved one to be like; the wall’s stones are clean; the cobwebs and dust found in the living room and kitchen are only a recent addition; the furniture is not yet covered by cloths, and it still feels... lived in. It is beautiful, and it’s the vacancy that’s the source of its melancholy. I want to create the feeling that Théa’s uncle should still be sitting there, in his favourite armchair, but no longer can.

If one were to venture onto the first floor, now that would be a different story. Being only one man, all to himself in this large home, he kept to the ground floor the most.

The garden and small greenhouse is the most lush of all, tended to until his very last day. From these vibrant elements, contrasting so heavily with Thea’s, we pick up clues on what kind of character he was, and invites us to understand what might have possibly happened to warrant someone apparently so full-of-life to be almost forgotten by her.

A two-floor, countryside estate. It is very lovingly cared after, and visually fashioned after the old, French farmhouses that the more wealthy, landed families used to own.

Ground floor blueprint.

Ground floor blueprint.

35

Ground Floor Layout

Light filters into the kitchen; the bed is made; a book lies on the coffee table, bookmark still in place; the vast, empty dining room has not been danced in for very long...

As though time refuses to march onward.

But to Théa, the house feels a lot more empty and suffocating at first than it truly is.

The sharp silhouette of furniture crowds the frames, almost creeping in on her, tangling her within a view of limited space. Her figure is distant and small in this family member’s home, who, according to her, is no better than a stranger. It is only as Théa’s stay in the home unfolds and she begins to open up more that she notices details that pertained to her uncle’s person. Such as the colourful pillows, or the type of landscape paintings hung on the walls, or the ornaments over the fireplace...

Even his favourite armchair is vibrant, the one place where he liked to start and end all his days with a warm cup of tea.

W HO E LSE I NHABITS THIS W ORLD?

39

C HRISTOPHE

Théa’s Gentle ‘ Uncle ’

Now let’s rewind just a bit... Remember when it was mentioned that the uncle Théa grew up knowing was “someone else entirely”? Well, here he is: the sweet Christophe.

Christophe and Christoff were the best of friends as kids. Their phonetically-twin name was a source of great amusement to the pair, and even the very instigator of their inseparable friendship. Though, unlike his more vivacious partner in crime, Christophe was a quiet boy, cautious of most things around him.

He liked to take his time with anything he did, and lived in a small, humble house in Vivrennes, not a countryside estate. With only a small voice to speak his thoughts, he was often swept up in the schemes of his younger friend.

Truly, double trouble.

He managed to survive the bombing of Vivrennes by not being in the town when it occurred. His home and his family, however, were not so lucky. When his best friend’s parents came to know of this, they took the boy in to live with them. Théa’s father was born shortly after, and Christophe grew up constantly reminded of the loved ones he lost.

40

Christophe’s quietness followed after him even into his older years. Reserved and reclusive, he was not all that much different to how Thea deals with her life when we first meet her.

He lived within the estate’s walls until his death, rarely inviting family over or interacting with them at all, for that matter. Any memories that Théa had of him or the house are sheened by the glowy veneer of childhood.

He hadn’t stepped foot in Vivrennes in a long while, but still caught up with his dear friend Adeline from time to time. As a consequence, locals knew as much about him as you might a protagonist of a ghost story; meaning, very little.

Near the end of the story, Théa comes to realise that the distance her uncle had put between him and her family was likely years upon years of guilt and pain of losing his family and best friend the way he did, no matter how much love or kindness his adoptive one showed him.

41

A DELINE the storyteller librarian

A very kind and elderly local that Théa ends up befriending during her stay in Vivrennes. Adeline is a thorough and down-to-earth person, and the hardships she’s had to face have instilled her with grace and dignity towards the life she has now. Having lived through the bombing of her hometown, her character is our presentday link into the past, being among the few people from back then who is still alive.

This gentle madam was the good friend of both Christoff and Christophe in her youth, and thus able to share with us both the fond and painful memories that are connected with the two boys she loved so dearly.

Presently, Adeline works at the municipal library, together in collaboration with the Tourism Office as a town guide, offering insightful tours for any curious visitors that wish to know more about Vivrennes and its history.

42

Adeline grew up alongside the boys. She acted as an older sister, often chastising them for reckless behaviour and keeping them out of trouble.

Or more specifically, trying to dilute Christoff’s penchant for mishaps with a good talking to and a firm hug, hoping to ward off his ‘bad influence’ on Christophe.

She was considered the reasonable one of the trio; reading fairytales to them; soothing the cries of a scraped knee; and, in her cheekier moments, challenging them to a race across the fields (which she always won, by the by).

.

43

. . But her kindness should not be mistaken for demurity!

CHRISTOFF’S P ARENTS

A charming, cultured pairing. At least, it depends on who you ask.

Christoff’s parents were not made exceedingly haughty from their upper-middle-class wealth, but that did not stop them from hosting lavish parties and inviting their friends-in-high-places to their countryside estate. They bore no qualms against their son befriending Christophe, the paysan boy, because they ‘understood’ there were few children to play with. They did, however, expect him to follow in his father’s large shoes. Inevitably, this meant Christoff was not allowed to get too attached to little Vivrennes and its people, seeing as they were bound to move.

His father was an engineer, specialising as an aviation industrialist. He worked together with the military establishment in designing fighter planes, but after the successful invasion of France in 1940 he was forced to work under the Luftewaffe and, as a consequence, he was often away from home...

Meanwhile, his mother was a Parisian seamstress who dreamt of becoming a blossoming, upcoming fashionista. But like many other dreams at that time, the rising of WWII torched it. Instead, she would help with mending and sowing clothes for the locals, though it mostly consisted of the former job. With resources becoming so sparse and precious, sowing in itself became a currency to trade for goods.

44

... but much like the other family members on Théa’s father’s side of the family, they were not very present in her life.

They passed when Théa was still very small. So small, in fact, she barely remembers having attended either of their funerals, and her father was never one who divulged much information about his youth, or his past. The grief of Christoff’s death had unavoidably spilled onto his life too, and his manner of coping involved moving far, far away from where he was born, and to never speak a word about the brother he never got to know.

45

they were also théa’s grandparents...

Burning Magnolia NARRATIVE

47

Our story begins

... with Théa receiving an offer to head to the tropics with a small expedition, at the cost of having to put her current research on a new subspecies of Solitary Wasp on hold. The entomologist gives a half-way reply, not particularly a fan of traveling so far, nor of letting go of her research even if it’s making little progress.

It is only when she returns home, exhausted, that the news of her uncle’s passing reaches her.

It is a shock at first, partly because Théa had forgotten the existence of this last relative of hers until now. To her displeasure, she’s required to head out of the city and to the countryside property to deal with the bureaucracy that ensues after a family member’s death.

And thus, she is forced to pack up her things, including her work, and head off.

It is quiet when she arrives. The air is wet with this morning’s mist, and when her foot steps onto the estate’s land her very first thought is:

Sell the house and be done with it.

But one day when looking through the garden, she encounters rustling through the foliage.

Thinking she saw a young boy in the midst of it, she follows after ...

... all the while scolding the intruder for playing around in a recently deceased man’s garden. It is at that moment she notices an elderly lady further down by the gates who pauses, looks in, then continues on her way.

To only add further complications onto the matter, Théa discovers that the house’s position hinders its internet reception. Unable to catch a good enough signal to work, she’s forced to head into town.

Still, before she can do so, she needs to fix her uncle’s bike that hasn’t been used in some time now. In the search for tools and an air pump, she happens across a half-broken, wooden toy plane in one of the shed boxes.

The whole day is spent at a café working, earning some funny looks from the locals, and she returns home around twilight. However... when she inserts the keys into the door of her uncle’s home, they do not budge.

Stupefied by the cadence of a song her father used to whistle when she was small, mixed in with the joyful chatter of several people coming from inside, she starts banging on the door.

A broad man answers. The two blink at one another, equally puzzled, and eventually their back-and-forth quizzing ends with him ordering Théa to leave his home. She manages to catch a glimpse of a very young boy just a little further in, surrounded by a glittering crowd of people with dashing outfits and cocktails. Their eyes meet briefly.

But once the door shuts in her face, all the lights in the house go out; the music stops; the chatter fades instantly. With her grip quivering, her keys miraculously work again, and she steps inside the deathly silent home of her deceased uncle.

Truly, the faster she can rid herself of this house, the better.

But providence has something else in mind for Théa.

The following day, while observing the attitude of a nesting Solitary Wasp, Théa encounters the same boy from yesterday night’s oddity. He startles her, and introduces himself as Christoff, he same name as her uncle.

Noticing her interest in the wasp, he badgers her into following him to Magnolia Grove, a place flooded with magnolia trees and all kinds of insects. For the first time, we see Thea’s expression lighten, as the experience feels almost unreal and magical... but alive.

In fact, reality steps back in and the Magnolia Grove is no longer there, nor are the flurry of insects... And nor is Christoff. Only one tree remains, and some buildings at Théa’s back.

She heads towards the buildings and finds herself wandering into a library. An elderly librarian calls out to Théa, noting her frazzled behaviour and, as coincidence may have it, it is the same lady who paused by the estate’s gates some days prior. She introduces herself as Adeline, and a dear friend of Théa’s uncle.

Théa offers to take Adeline to her uncle’s house, if she’d like to see it one last time before potential buyers come around. She accepts, and the two spend a brief afternoon there. After some reminiscing and Théa telling her new acquaintance about her line of work, Adeline mentions that the town has a beautiful festival next week she should stick around for.

Christoff appears to her that evening asking her if she will go “too”, referring to his father who has been called away - due to the war. The two fall asleep in the garden after sharing a lengthy discussion where they begin to open up to one another, and Théa awakens to the cold feeling of dew dropping onto her nose.

Whether by a piqued sense of curiosity, or something else keeping her there, Théa delays her return trip and decides to stay for the festival.

A certain sweetness fills her as she walks down the streets, lined by colourful pennant flags.

She passes a long queue to a sweets stall, but the further down it she walks, the greyer the shadows seem to loom. The people in the line shift from families enjoying their day, to young and elderly women, clutching ration tickets in one hand and small children with the other. Cries emit from head of the line, and Théa sees a young boy being hounded at by a German soldier for stealing liquorice sticks and a wooden toy plane: The same one she found broken in her uncle’s house.

Without thinking, she calls out in order to help the child and, with this as the perfect decoy, Christoff springs out from a hiding spot, grabs a handful of liquorice sticks and makes a run for it. This allows the other boy enough slack to wriggle free and run too, with Théa panickedly tailing after them.

Once a safe hiding spot is found, Théa scolds them for their dangerous behaviour, and a teenage girl chimes into it; none-other than a young Adeline. Acting nonchalant, Christoff teases his demurer partner-in-crime for not having stolen some paint to decorate their new toy with. Théa has them swear not to thieve anything else if she helps them paint it.

Adeline thanks Théa for keeping an eye on them, before goading them away.

Lucky for Théa, it appears that her research is picking up speed, as she receives an impromptu invitation to host a presentation back in the city. She accepts immediately, disregarding entirely that the day of the presentation is the same day she promised the boys to paint the toy plane.

After a successful presentation of her findings so far and their possible implications, the topic of the trip to the tropics comes up and, again, Théa is unsure. She’s shown the team for the expedition, but then when she latches onto the sight of one of the scientists sharing her uncle’s name, she begins to feel unwell and undergoes a mild panic attack.

She feels compelled to return to her uncle’s home instead, but her return is met with heavy silence. Théa searches for Christoff, apologising, and does not find him. Thinking this is punishment for having broken her promise, she’s unable to concentrate on her work and struggles to successfully host buyers interested in the house.

Disheartened, she seeks out Adeline, who is very happy to see Théa again and ushers her inside for some tea. The elderly woman shows her many old photographs. A handful of which have her, Christoff, and that other boy from the festival. She tells Théa she can keep one with her uncle, and finds a photo of the three playing that reads:

‘Summer 1938. Adeline, Christoff, and Christophe.’

On her way home that very evening she hears the crackle of an old radio from the side of the road.

Christoff and Christophe are there, squatting together beneath some bushes. Surprised and even briefly relieved to see them, Théa tries calling out to them but is shushed harshly in response.

War-riddled news shadows the air, as an increasingly frightened Christophe tries to force Christoff, who is obsessively listening to it, to turn it off.

This escalates into a fight between the boys as both succumb to panic and terror, ending in the toy plane breaking in half.

It is also now that Christophe, who hadn’t explicitly been named until now except in the photograph, is called to by his friend during the argument.

When Théa tries her best to intervene, this time she notices that neither of them listen to her, nor seem to notice her even being there. When Christophe runs away crying, he phases right through her. When she tries to put a hand on Christoff’s shoulder, her fingers fall through him.

One half of the plane is thrown out into the field by Christoff, the other half runs away with Christophe.

And thereafter, she has no more visions. She sees no more of Christoff, or Christophe either. Everything is just back to normal, but ever worse than before as she is forced to confront the loneliness that she has felt all her life, all at once.

This state pushes her to actively try and trigger a vision to happen. She frantically revisits places where they’ve been together; she ventures onto the second floor of the house, where she finds a child’s room left untouched; she even tries to fix the toy plane, but her only accomplishment is a stubbed finger. Nothing seems to work, and she’s left to soak in dread.

Until, there is a terrible storm. Théa thinks she sees Christoff dashing for the fields outside her window and, instantly, she bikes after him. But as she passes the vacant part of countryside between her uncle’s house and the town, flashes of bright light, crumbling buildings, and panicked women and children surround her.

In her terror, the bike spirals out of control...

Adeline is there when Théa wakes up in hospital. She is the one to take Théa home, and on the way the two begin speaking.

When Théa questions Adeline what happened to her and her uncle’s shared friend - Christoff - a heavy-hearted Adeline goes on to explain that he died in the Bombings of Normandy. They sit in a few moments of silence, as Théa appears to be expecting what comes next: hopefully not a plot twist at this point, but rather a confirmation for the audience, it is revealed that Christophe is the uncle Théa came to know.

The night of the fight, Christoff had wanted to apologise to his friend, and headed into town to visit him, while Christophe did not actually return home straight away and, because of it, survived. Christoff’s family who had now lost their son, and Christophe who lost his family, take the boy in to live with them. Théa’s father was born shortly after the end of the war, making Christoff her blood-related uncle.

Théa asks if they can make a stop somewhere before arriving home, and Adeline obliges. She begins searching frantically for Christoff’s half of the broken plane but, with all the time that has passed, she of course cannot find it, devolving into a breakdown. She cries into Adeline’s shoulder, beneath the last magnolia tree on the hill.

He never did get to paint it.

That night Théa prepares two cups of tea, and brings them into the lounge, together with the broken half of the toy plane.

She sits in the seat directly in front of - what she’s now learnt is - her uncle’s favourite armchair, sets down everything on the coffee table between them, and begins to talk to the empty air. Simply speaking her mind freely on what she would’ve liked to express, had she the chance.

Sniffling suddenly fills the silence, one that is not her own, and it takes a moment for her to realise that it originates from behind the armchair. Christoff is curled up there, crying, and after some moments of consolation she encourages him to join her, asking him if he too has some words he’d like to say to her uncle - and his best friend.

Théa pulls Christoff in for a tight embrace, and for a fleeting moment, the thinly visible phantom of an elderly Christophe flickers in the armchair behind them, peaceful and asleep, before disappearing again.

The world whirs with warmth as she hears a small voice in her ear murmur:

“Until next time, Théa.”

Théa doesn’t know exactly when the embrace ends, only that at some point her eyes reopen and she finds herself at the foot of her uncle’s armchair, with her arms enveloping her own body.

The story comes to a gentle close with the house being opened as a historical site that Adeline happily manages, while Théa decides to round up her research with the solitary wasp.

It’s time to start anew; perhaps that overseas job offer is still available... FIN.

79

M EDIA L ANDSCAPE

81

M AIN MEDIA

As you have just seen from the narrative segment, I envision this project as a perfect fit for a featurelength, 2D animated film, aimed at audiences of young adults and above.

Why an animation?

Too often I feel that in Western media the potential for telling more mature stories via animation is ignored because of the long-standing preconception that animation should be for children’s eyes. Or that in order to convey more mature themes we must disguise them by using children’s stories as a vessel. An instance of this is the endless debates on whether one of my favourite books, ‘Le Petit Prince’ by Antoine de SaintExupéry, is to be coined as a children’s book or not, simply by the way it is stylistically portrayed.

Burning Magnolia touches grave themes, circulating around trauma and war, without it exactly being a war-story. Rather, it focuses on the lives it has affected, both during and in the generations to come. This is why this story is relevant now and why I would like it to reach a broader, adult audience – I am talking to the people like myself who have had these kind of stories passed down by their mother, their father, their grandparents, dear friends... and I am urging them to listen.

This story is for you, for us.

Why not have it as a cinematic film?

Impossible! In the words of Remi Chayé , director of L ong Way North, animation is a ‘powerful combination’ between cinema and drawing: you have the movement, the soundscape, the atmosphere of cinema, paired with the freedom, elasticity and emotivity of illustration. In other words, the finest ingredients to completely transport you elsewhere for 90 minutes or so of your time.

There is a ripening moment for animation right now, where we can test the boundaries of what we expect it to be, whether visually, thematically, story-wise, etc...

K laus , Guiller Mo del Toro’s P inocchio, A rcane ... Albeit these all being very different projects with very different scopes, my point is that they have set a fresher tone for the animation scene. Whereas some might see it as the bar being raised higher, I see it as a crack of light opening up: a window of opportunity. This doesn’t mean completely reinventing the medium, or ‘making the next best thing’, but rather proof that animation is definitely more versatile than we give it credit for. It’s our chance for animation to come back and truly flourish, building upon the foundations its predecessors have left.

What about it being 3D animated?

While there are some projects that lend themselves better to 3D animation, Burning Magnolia’s story, characters and atmosphere is one that I can see benefiting from that special feeling only 2D animation can emulate. CG is developing and its results are dated by it, whereas the craftsmanship of 2D doesn’t age as swiftly.

Plus, with a heavy outflow of serialised 2D animations (whether children or adult shows) and feature length films reserved to 3D, a traditionally animated film will no doubt stand out. So while, yes, 3D has increasing demand, this also makes it a saturated market. If you look at animated movies from the past and of the coming years, all of them are (with the exception of some animes, who are also dipping their toes in 3D now) CG animated.

I would even like to argue 2D has an ardently loyal fan base. There is a large audience, even adult audience, that misses the call of 2D films. Particularly those such as myself who grew up on Ghibli, Dreamworks and Disney, with later on studios like Cartoon Saloon and SPA Studios coming along to reignite the flame. Blogs and podcasts like Tito W. Jame’s A dUlt

A nimation R e V olU tion (published on none other than comiccon.com) prove that there is a present fan-base looking forward to the release of animated creations.

Any concrete examples, then?

I find that FLEE – the only traditional animation that scored, not one, but three Academy Award nominations in 2022 – is an excellent example of the point I’m trying to make.

What’s

something new?

Not only does it touch on very real and heavy subject matters, it takes the documentarylike lens and unravels it through animation instead of film. In an interview with Jonas Poher Rasmussen, he mentions how the visuals on screen reflected the thread of emotions, shifting accordingly from a style that is more grounded to something more abstract. This is only possible through animation; the detachment from reality (meaning, you are not witnessing real people, real environments, etc. on screen), is what ultimately brings you closer to the truth and core meaning of the story.

And this is precisely what applies to Burning Magnolia.

83

What other forms can Burning Magnolia take?

But of course the possibilities do not just end there. Here are just a couple more ideas of what can come out from this project!

Video Game:

The premise can render itself very well to a Video Game too. With the aspect of the two worlds separated by time, Thea gathering understanding of her past, and the history of the town, it could make for a more introspective, experiential singleplayer adventure. Similarly to Night in the Woods, the player could be focused on connecting with characters through a more linear narrative, without it having as wide of a scope as an open-world RPG with several mechanics. Or another example could be the point-and-click game Fran Bow, where you must ‘switch’ between two different worlds in order to progress the storyline, discovering objects and clues of information that help uncover the mysterious narrative.

Graphic Novel(s):

There is potential for this world to expand into comics, and BBC’s long standing genealogy TV series, ‘Who Do You Think You Are’, is going to have my back on this. Allow me to explain: the very core that ties this world together is its theme of ancestral trauma, and that being able to understand your past can help shed light on your present and future. I don’t believe there is one person on this planet that would tell you they’re not fascinated by their lineage.

So I ask, why just stop at Théa’s story?

There is a whole world around us just brimming with history. With the right research and attention, it could even be a way of offering representation to different cultures that are not often spoken about, with creators from said cultures to illustrate and tell these stories. Each Graphic Novel could spotlight a new character from a different place in our world, and follow their story as they begin to experience visions of their ancestral past – whether that be from 100 years ago, or 1000!

84

Museum Exhibition:

Another proposition could be expanding the universe through a historical exhibition, dedicated to showcasing the change of time. What could make this different from other war-centric exhibitions is that it would mostly focus on displaying the changes and the effects war brought onto the civilians; the battle of every day life, rather than the one fought on the battlefields. This could be via clothing, photographs, utensils, or, like in my example above, children’s toys... Illustrations and artwork spanning across the walls would provide a clear narrative for visitors to follow along, while also making the exhibition open for most any kind of audience to experience.

85

And with that, the curtains close on Burning Magnolia... For now.

My mentor DJ Cleland-Hura, for his guidance, help and support. You understood my vision from day one, and helped me in crystallising it into something real and close to my heart.

Peter Dyring-Olsen and Erik Barkman, for having me in this wonderful Bachelor program. It still feels like yesterday that I started Graphic Storytelling; the time I’ve spent here is very special and will be forever burrowed into my being.

Joe Kelly, Mikkel Mainz, Steven T. Seagle, Cecil Castellucci, Joana Mosi, Mads Skovbakke, and Martin Rauff for overseeing the creation of this project. You all appeared at different times during production, but being able to bounce off ideas with you, or even just sharing a motivating pep talk, has helped me consider my concept from different angles.

My classmates, for the inspiring years we have spent together. I’ve learnt so much from you all, and you’ve encouraged me to aim not just for the stars, but even further; for the galaxies and beyond.

A special thank you to the other ‘Story Biblers’ for sticking together during this intense Final Production!

Petra Hauthorn Svennevig, for all the times it was just us two in the studio, chipping away at our projects, but in each other’s company.

I would like to extend my most heartfelt thanks to...

88

This is a final production from GRAPHIC STORYTELLING , the animation workshop, via university college, 2023

and of course thank you for reading.

SKETCH OF VIVRENNES STREET prior to WWII.

SKETCH OF VIVRENNES STREET prior to WWII.

Ground floor blueprint.

Ground floor blueprint.