16 minute read

Table of figures 28

Advertisement

2.2 Activating the ground as a spatial strategy

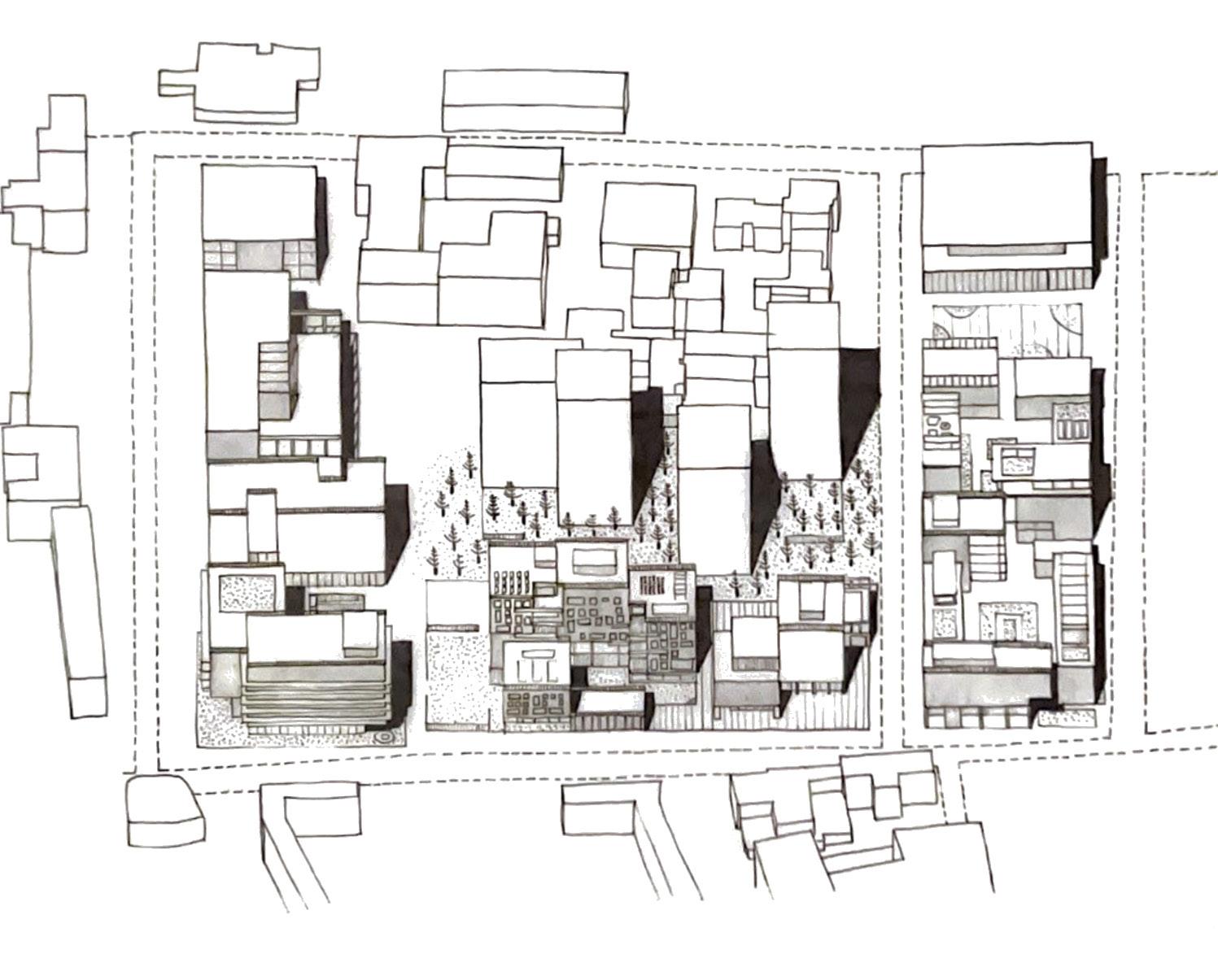

Coming back to the role of the landscape as a structuring device, we can see how it works differently with the three types of care environments. The landscape that forms the perimeter of the block is porous enough to support the previously blocked east-west direction of movement and improve the micro mobility inside the block. If we look at the residential setting in the east, we can see how the ground floor starts to manage transitions between exterior spaces with different levels of openness. It creates a gradual shift from the highly permeable market square intended for community events and more collective experience, towards a quieter semi-public residential space to the south of the strip. The transition occurs through a sequence of green enclosed courtyards and corridors of different dimensions. The profiles of the buildings start to play an important role in these sequences. The ‘nudges’ in profiles create overhangs and additional bounded spaces on the ground floor. Each of these spaces becomes more than a landscape element but rather a social device: one can imagine a diversity of scenarios for which they are fit. From reading a book on one’s own, a family picnic in the fresh air to a big gathering with neighbours.

While transitioning towards the nursing home, the ground changes its character and is ‘thickened’ by creating additional levels of lowered courtyards and lifted terraces. The landscape around the nursing home is additionally defined by low partitions. These tools allow the care facility to find the required balance: the ground floor is less porous and offers more intimate quiet spaces for the patients’ time outside but it does not border off the area from the rest of the cluster. The fact that the heart of the block is densified and extended vertically, liberates the ground around it and allows to conceive a completely different version of the landscape. The care environment in the centre ends up being located within a rather contained and protected park setting while still taking advantage of the access to the services and activities provided by the artefacts around it.

18

Exploration of the ground as a structuring device and facilitator of event 19

20

Residential units of the cluster. Experimenting with layering in the drawing to reveal the role of the landscape and its relation to the ground floor organisation

Cluster. Assisted living facility

2.3 Extended threshold. Elevation as a tool for working with phenomenal transparency

While thickened ground and landscape of different characteristics are useful organisational devices, the cluster also stresses the role of elevations in establishing hierarchies, directionality and transparency.This vocation of the design can be understood by looking into the notion of ‘phenomenal transparency’ proposed by Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky . As opposed to literal transparency that suggests an immediate and direct reading of the building planes, the phenomenal one invites to see the lateral planes relationships, their layering, continuity and hierarchy. Rowe and Slutzky took their starting point in the aesthetic mode of reasoning they observed in some of the 20th c. paintings5. It introduced a new type of visual experience that embraced ambiguity and was open for interpretations. When translated into architectural practice, phenomenal transparency is a tool for enabling us to think that any moment in space belongs to more than one spatial system, ‘can be assigned to two or more systems of reference’6 .

In the case of a cluster, such layering is associated with the visual experience of moving through space and is supported both at the level of the morphological organisation and at the scale of the elevations thresholds. Instead of simply facing the street, each artefact establishes frontality according to its needs and priorities. Consequently, new networking opportunities are created in the depth of the block as things are drawn in relation to each other. The cluster suggests to treat the elevations not as boundaries but as useful organisational devices that allow to extend the notion of entrance and thicken the threshold between the interior and exterior. Facades become almost freestanding devices that articulate the ambiguity of these two conditions and at the same time allow to move between them seamlessly.

In order to explore the notion of phenomenal transparency as an architectural tool, the work used several cases of residential and care environments. The aim was to investigate through drawing the vertical surfaces conditions and the way they translate the notion of a threshold.

5 In their essay Rowe and Slutzky introduce the differences between 2 notions of transparency by comparing ‘The Clarinet Player’ by Picasso and ‘The Portuguese’ by Braque. 6 Colin Rowe, Robert Slutzky, Transparency (Basel; Boston: Birkhäuser Verlag, 1997): 61. 21

Photographer’s house / 6a architects 22

Photographer’s house / 6a architects 23

Residential care home Andritz / Dietger Wissounig Architekten

24

Residential care home Andritz / Dietger Wissounig Architekten 25

Villa Savoye / Le Corbusier

26-27

Implications of the phenomenal transparency notion in the cluster design.

2.4 Synergies

The cluster brings together a research centre specialising in biomedical work, care facilities and key-workers housing. This combination allows to improve the process of research, education and practice for medical workers, caregivers and researchers. The staff gets a chance to get additional education or conduct research in close proximity to their future (or current) place of work. They can gain hands-on professional experience at a care facility while still receiving their undergraduate education and then continue building their career as employers at the same place. The science workers on the other hand can receive the information and field data from the first hands and in a short period of time. In addition to that, the research centre might become one of the main anchors in terms of civic value generation for the cluster. We can learn from the trends mentioned earlier and imagine a facility that opens its doors to the wider public and engages not only with trained professionals, but also attracts local residents as well as visitors from wider urban areas to participate in public programmes, educational workshops, conferences, etc. In addition, two pavilion centres occupy prominent corners of the cluster: cultural and learning hubs. Their position and programme allow us to see them as potential first steps in the neighbourhood regeneration. Placing them in accessible locations and bringing a new civic offer to the area would kick-start the implementation of the cluster concept. Today, when looking for a type of building organisation that could handle complexity of various synergies and stakeholders collaborations, one of the common answers is a large-scale flexible container that is anticipatory in nature7. It allows to create short-term interiors that are future-proof in their ability to easily transform over time. The proposed cluster suggests an alternative way of operating within buildings like the cultural, educational or research centres. It offers creating relatively small spaces that reject the notion of vertical ‘stack’. These spaces can still handle complexity by valuing double-height spaces and creating alterations in section, aligning with the principles of the ‘tree organisation’ rather than with the ‘domino’ scheme.

2.5 Inner periphery future:

In his essay Rem Koolhas puts forward the concept of a ‘Generic city’ as a tool for liberating from the straitjacket of identity. For him our constant obsession with character rooted in history and context, insistence on the importance of the central city are a dead end, resisting city expansion, interpretation, renewal, contradiction8. He does, nevertheless, name a city that is an exception among those imprisoned in their identity – London. ‘London – its only identity, a lack of clear identity – is perpetually becoming even less London, more open, less static’9. London is truly a phenomenal city, a laboratory of urban conditions. However, perhaps we haven’t been paying enough attention to some of them, maybe we should indeed shift our attention from the exhausted city centre10 towards peripheral settings. The London Vauxhall area where the

7 For example: Here East UCL campus, Med City Campus in Whitechapel, London. 8 Rem Koolhas, “The Generic city”, in B. Mau and OMA. S,M,L,XL (New York: The Monicelli Press, 1995): 1248-1264. 9 Ibid, 1248. 10 For the city centre it is getting harder and harder to deal with the growing population pressures, construction limitations due to the high density of the built and an overlay of requests from different stakeholders. 28-29

Exploration of the cluster scenery and spaces through speculative drawing

proposed cluster is located, can serve as an example of such an inner periphery area that has been abandoned for a long time but can now be seen as an exciting ground for exploration and change. As mentioned earlier, the last few years showed us that there is a need to rethink the issue of service provision in these kinds of urban settings. There are multiple reasons for that including changed work-life patterns, emergence of new collective formations and requalification of urban domesticity, questions of innovation in housing11. The notion of the dwelling, of housing in general becomes very important. As Dogma put it: ‘By virtue of their life in common, the household becomes a clearly discernible social-economic unit whose role in the organisation of the city is fundamental’12. In other words, the complex of the domestic realm is something that is closely affiliated with other domains of the city, and should be reconceived as an urban project that incorporates services related to fields like culture, education and care. In the case of the wellbeing realm, housing can become a subject to insinuation preparing for lifelong needs including those of care and health provision if we treat it as a liberal environment that is constituted around sophisticated understanding of everyday life and the way people relate to each other within a group.

11 The reasons behind the changing patterns of urban domesticity and examples of new types of collective formations were researched by the author in the ‘Home-platform for change’ essay [Housing and Urbanism, Domesticty course]. 12 Pier Vittorio Aureli, Martino Tattara, Living and working (Cambridge : The MIT Press, 2022):10. 3 Vauxhall

campus organisation for the new version of care environments

The character and qualities of the Vauxhall area themselves indicate why it is a ground of great potential for the future redevelopment. An area with an industrial past, Vauxhall had been forgotten by developers for a long time due to the lack of proper connections to the North of London. Now it is a residential neighbourhood that is well-linked to the central areas, with an extremely mixed housing offer: from social housing estates, opportunistic refurbishment projects and Georgian and Victorian vernacular fabric to high density high-rise developments that flooded the riverbank area. The concentration of height and capital along the river boosts the land value. In addition to that, Vauxhall has large and ambitious developments like Battersea Power station growing at its doorstep which puts even more pressure on the housing development and need for densification.

From a morphological point of view, the fabric of the area is rather broken and lacks legibility. It results in a diverse set of block geometries and sizes that can be found in the area: from ‘distorted’ sites that have to negotiate between the curve of the river and the line of the railway and fairly regularly shaped blocks. The blocks are shaped by service roads and dead-ends rather than functional streets, the area is missing an effective multidirectional mobility system. However, despite all these qualities Vauxhall is an area that handles differences and still manages to sustain active and intense environments within its blocks13. The way to proceed is to find a certain logic behind the fragmentation and incoherence and start building on the possibilities it offers. For the cluster design proposition, this logic can be found in the landscape assets and block structure of the area.

If we look at the Vauxhall landscape characteristics, we can notice that a series of parks, courtyards, and public gardens starts to form an interconnected system that flows through the blocks. If we consider this network of highly differentiated landscape pieces together with the large dimensions of the blocks we find in Vauxhall, we can see an opportunity for these sites to be rethought in terms of the campus organisation supported by radical change in typological offer. Traditionally, the campus organisations are associated with knowledge environments, university realms that would be rather contained. However, things are changing14 and there are campus characteristics that can be useful not only for university premises.

Here the notion of a campus should be defined more clearly as it is understood and implemented in this particular work. The campus is not relying on the streets as an organisational tool and is mainly accessible for pedestrians, bikes, service vehicles, but not the cars. As we already noted, streets in Vauxhall and specifically the ones framing the site in question are already underperforming and do not deliver any important urban function. Moreover, currently the potential of the landscape that is present is not being used fully. The potential of a campus is in articulating the relationships between the artefacts that constitute its built part and the landscape that becomes

13 Vauxhall already has an interesting offer of cultural venues, small local galleries like Newport Street Gallery, Cabinet Gallery. It also sustains rather active and popular venues like the Black Prince sport Community Hub, or the Vauxhall City Farm. 14 Campus organisation is used to organise the residential neighbourhoods like Mehr als Wohnen or Eddington project for key-workers in Cambridge. However, these examples are still located in the peripheral areas.

30

Vauxhall landscape network connecting blocks with potential for campus-based redevelopment 31

Vauxhall diverse typological offer: predominance of the linear type in different variations, acumulative types and concemtration of density and height along the river.

a hard-working part and much more than just a natural element, a ground. It aligns with what Colin Rowe was arguing for: a balance and dialogue between the space and the objects, ‘a solid-void dialectic which might allow for the joint existence of the overly planned and the genuinely unplanned, of the set piece and the accident, of the public and the private, of the state and the individual’15. Establishing these relationships, campus offers a layered system that can accommodate complexity. And it is crucial when we are looking to house crossovers between stakeholders, settings and genres. Such crossovers mean that every ‘ingredient’ is entering the scheme with its own services, specialisms and requests. While care environments need a certain degree of privacy and security, a research and educational institute has to be ready to accommodate a high footfall, offering additional spaces for collective experiences both inside and outside. By virtue of its size and flexibility, campus is exactly a framework that can allow all these environments to come together, negotiate their needs and identity and form an administrative network. Exactly how we are looking for a balance between proliferation of a liberal subject’s freedoms and its relations with a wider collective, within a campus we want each component to stay independent but still offer and use services beyond its border.

32

Combination of the existing block stucture with the landscape assets as a starting point for the design.

15 Fred Koetter, Colin Rowe, The Crisis of the Object: The Predicament of Texture (Perspecta, vol. 16, 1980): 109–141. 4 Conclusion

Let’s accept the metaphor of the architects’ job being similar to the one performed by a surgeon or a doctor16. One has to become diagnostic of the condition he or she is facing and find a proper solution bearing in mind the experience that the field had already acquired and the possible external influencing factors. It is exactly in this manner how the design proposition of the cluster was put forward. The project rethinks the role care and wellbeing are playing in our cities today and the way they are proliferated in the built environment taking into account the shifts that happen in our perception of a dwelling, domesticity in general, education and service provision. It argues for opportunity of reviving a broken urban condition by introducing a new care domain, approaching it from a new morpohological starting point rooted in the existing urban condition. It contributes to the argument about new emerging crossovers and need for reconceptualising housing as an urban project via other domains. The proposition learns from the precedents found in the architectural practice and rethinks them in order to initiate change across multiple scales: from the dwelling to a wider urban whole. From the point of view of identity, the proposition is aiming at helping Vauxhall to acquire a new identity through a new vocation of a Care-full city.

16 This argument has been extensively used by Anna Shapiro within the Design Workshop Term 1 and 2 process.

5 Bibliography

Allen, Stan. “Infrastructural Urbanism”. In Points + Lines: Diagrams and Projects for the City. New York: Princeton Architectural Press (1999), p. 40-89.

Allen, Stan. “Mat Urbanism: The Thick 2-D”. In Le Corbusier’s Venice Hospital and the Mat Building Revival, edited by Hashim Sarkis, 118-127. Munich London New York: Prestel Verlag, 2001.

Aureli, Pier Vittorio, Martino Tattara. Living and working. Cambridge : The MIT Press, 2022.

Christiaanse, Kees, Kerstin Hoeger. Campus and the city: urban design for the knowledge society. Zurich : Gta Verlag, 2007.

Dahir, James. The Neighbourhood Unit Plan, its spread and acceptance. New York: Russel sage Foundation. 1947.

Koetter, Fred, Colin Rowe. The Crisis of the Object: The Predicament of Texture. Perspecta, vol. 16, 1980, pp. 109–141.

Koolhaas, Rem. “The Generic city”. In B. Mau and OMA. S,M,L,XL. New York: The Monicelli Press (1995), p. 1248-1264.

Panerai, Philippe. Urban forms : the death and life of the urban block. Oxford : Architectural Press, 2004.

Rowe, Colin, Robert Slutzky. Transparency. Basel; Boston: Birkhäuser Verlag, 1997.

Ungers, Oswald Mathias. The dialectic city. Milano : Skira, c1997.

Venturi, Robert. Complexity and contradiction in architecture. London : Architectural Press, 1977. 6 Table of Figures

01 Drawing by the author

02-04 Jieyi Lu, ‘Care hub’

13-14 https://www.archdaily.com/565058/peter-rosegger-nursing-home-dietger-wissounig-architekten

15-16 https://www.archdaily.com/922550/belle-vue-senior-residence-morris-plus-company/5d4a471b284dd12fd700047a-belle-vue-senior-residence-morris-plus-company-photo

17-32 Drawings by the author

AA School of Architecture May 2022