6 minute read

studEnt Essay

What’s in a name? Clean meat is served

Joy Sim, Student, University of Otago

This article was awarded second equal prize in the Food Tech Solutions NZIFST Undergraduate Writing Competition 2020. The annual competition is open to undergraduate food science and food technology students who are invited to write on any technical subject or latest development in the food science and technology field that may be important to the consumer.

Introduction

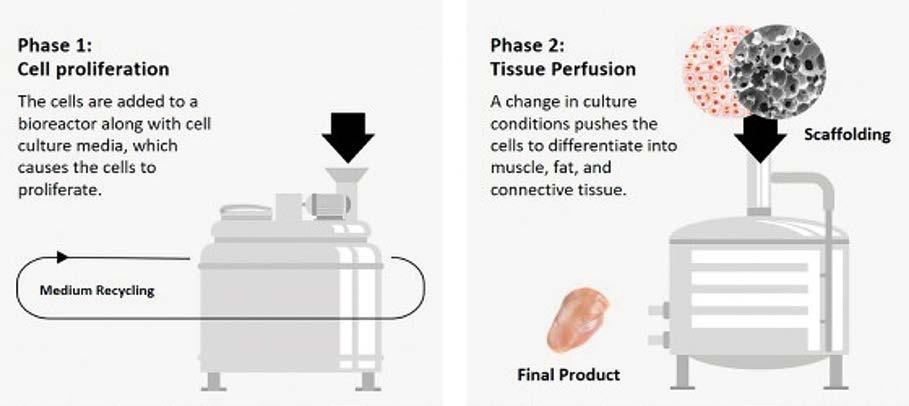

Clean meat (also called cultured meat or lab-grown meat) is real meat produced through genetic engineering without the need for animal slaughter. Starting with a small sample from the muscle of a living animal, stem cells are extracted and fed with nutrients to grow under special conditions. This prompts them to differentiate into fat and muscle cells before harvesting into “clean meat”, identical to conventional meat at molecular level. In marketing a food product to consumers, the name used influences consumer perception and sales. Unappetising names like “cultured meat” have led consumers to associate the product with unnaturalness and science, turning them off before the product hits the shelves (Bryant & Barnett, 2019). According to Laestadius and Caldwell (2015), such names promote the naturalistic fallacy in which consumers believe, without evidence, that the product is unnatural and is therefore bad. On the other hand, “clean meat” was found to produce the highest consumer acceptance and positive behavioural intentions to trying the product (Bryant & Barnett, 2019). Advocates are thus pushing for “clean meat” to be used in popular media and discourse. By 2025, clean meat and its substitutes are foreseen to amass sales of up to NZ$11.3 billion (Flaws, 2019a). The industry is merely 5-10 years away from scaling up clean meat burgers (Beef and Lamb New Zealand, 2018). Cost was the biggest barrier to market entry at USD$330,000 in 2013, but each patty currently costs about USD$10 and the cost is expected to continue to decline rapidly (Flaws, 2019a). Against the backdrop of increasing financial viability and with multinational companies like Fonterra jumping on the bandwagon to invest in clean meat (Flaws, 2019a), is there a clear justification for clean meat production?

The meat of the matter

An increasing number of New Zealand consumers want to know where their food comes from (Laestadius & Caldwell, 2015) and are concerned about sustainability issues, with 30% more vegetarians in the country from 2011 (Roy Morgan, 2016). However, New Zealanders still remain one of the world’s highest consumers of meat at 100kg per person in 2013 (Ritchie, 2019). While red meat consumption in the country has dropped, pork and chicken consumption continued to increase over the past 10 years (OECD, 2019). Clean meat is said to be the solution to satisfy consumers’ desire for meat without the greenhouse gas emissions, land, and water costs associated with conventional meat production. Recent studies have cautioned the potentially higher energy input and environmental footprint of clean meat production (Lynch & Pierrehumbert, 2019). Nonetheless as research continues to break the technological barriers to commercialising clean meat, the biggest barrier remains in consumer acceptance, with surveys highlighting inconsistent results across different countries. Qualitative studies have revealed common objections to be perceived unnaturalness, fear of risks to public health, taste, and price concerns. (Laestadius & Caldwell, 2015; Verbeke et al., 2015; Mohorcich & Reese, 2019)

What will Kiwi consumers choose?

Clean meat could become as inexpensive as conventional meat in just a few years. When forced to choose between clean meat, conventional meat and other alternative proteins in the market, what will Kiwi consumers choose? Tucker (2014) conducted qualitative focus groups throughout the country with 69 individuals on clean meats and insect consumption in order to identify opportunities for reducing meat consumption in the country. Participants were shown pictures of intensive agricultural farming, low input farming, GMO, clean meat, and insect eating, and were asked to share personal thoughts on whether they espouse those practices (Tucker, 2014). Tucker’s (2014) research highlighted overall negative attitudes towards clean meats, with 55% opposing the idea of clean meats becoming a diet staple due to taste and unnaturalness. The research showed that younger males, who are more knowledgeable, and city dwellers in New Zealand were more accepting of clean meat. (Tucker, 2014; Flaws, 2019) To encourage consumers to try clean meat, it has been suggested that marketers highlight the environmental benefits of clean meat in comparison to conventional meat. (Verbeke et al., 2015) However, willingness to try does not reflect purchase intentions in a real marketplace setting. The dearth of research surrounding consumer attitudes toward clean meat in New Zealand warrants more work being done in this area.

Conclusion

Conventional meat farming has been said to be one of the biggest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions. In response to climate change and the growing world population, clean meat promises to be the solution to preserving the environment and to satisfying consumer thirst for meat. However, consumer acceptance remains a huge constraint. While the name "clean meat" has enabled greater buy in, consumers are still sceptical about the technology and its potential risks to health. People want to know where their food comes from and food marketers have to be prepared to tell a compelling story. More research thus needs to be done to understand how clean meat can be marketed in New Zealand. Clean meat has found great success in Israel, not because of its name, but because marketers have managed to appeal to the values of its people. Israel is home to the most vegans per capita in the world. (Leichman, 2017) Bearing in mind that regenerative farming using grazing animals has been found to be crucial to sequestering carbon back into the soil to restore the environment (Flaws, 2019b), it seems there is still a place Proposed production of clean meat at industrial scale

for responsibly produced conventional meat and alternative proteins in the market, even as clean meat becomes commercially viable. As the industry searches for ways to serve protein to the world, perhaps it is the collective efforts of reducing our environmental footprint that would justify all the toil. References Beef and Lamb New Zealand. (2018). Future of Meat. https://beeflambnz. com/sites/default/files/levies/files/Alternative%20Proteins%20summary%20 report.pdf Bryant, C. J., & Barnett, J. C. (2019). What's in a name? Consumer perceptions of in vitro meat under different names. Appetite,137, 104-113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.02.021 Flaws, B. (2019a). Fonterra is investing in artificial meat, but would you eat it? Stuff NZ. https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/111546089/fonterra-isinvesting-in-labgrown-meat-but-would-you-eat-it Flaws, B. (2019b). Regenerative farming: can meat save the planet? Stuff NZ. https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/farming/114537590/regenerativefarming-can-meat-save-the-planet Laestadius, L. I., & Caldwell, M. A. (2015). Is the future of meat palatable? Perceptions of in vitro meat as evidenced by online news comments. 18(13), 2457-2467. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980015000622 Leichman, A. K. (2017). Israel has most vegans per capita and the trend is growing. https://www.israel21c.org/israel-has-most-vegans-per-capita-andthe-trend-is-growing/ Lynch, J., & Pierrehumbert, R. (2019, 2019-February-19). Climate Impacts of Cultured Meat and Beef Cattle [Original Research]. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 3(5). https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00005 Mohorčich, J., & Reese, J. (2019). Cell-cultured meat: Lessons from GMO adoption and resistance. Appetite, 143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. appet.2019.104408 OECD. (2019). Meat consumption https://data.oecd.org/agroutput/meatconsumption.htm Ritchie, H. (2019). Which countries eat the most meat? BBC News. https:// www.bbc.com/news/health-47057341 Roy Morgan. (2016). Vegetarianism on the rise in New Zealand. http:// www.roymorgan.com/findings/6663-vegetarians-on-the-rise-in-newzealand-june-2015-201602080028 Tucker, C. A. (2014). The significance of sensory appeal for reduced meat consumption. Appetite, 81, 168-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. appet.2014.06.022 Verbeke, W., Marcu, A., Rutsaert, P., Gaspar, R., Seibt, B., Fletcher, D., & Barnett, J. (2015). ‘Would you eat cultured meat?’: Consumers' reactions and attitude formation in Belgium, Portugal and the United Kingdom. Meat Science, 102, 49-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2014.11.013 Wilks, M., & Phillips, C. J. C. (2017). Attitudes to in vitro meat: A survey of potential consumers in the United States.(Research Article)(Author abstract). PLoS ONE, 12(2), e0171904. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0171904