8 minute read

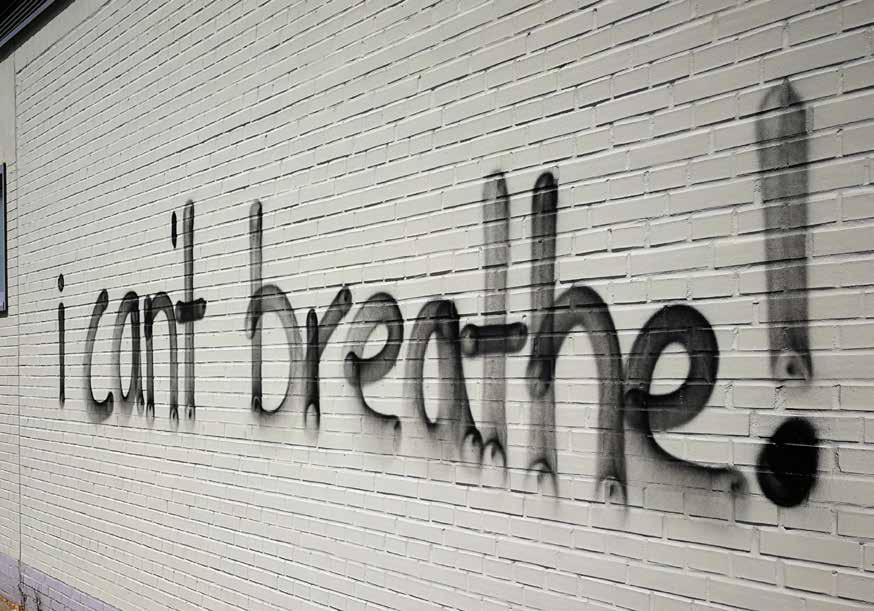

Irish republican voices against racism

The police murder of George Floyd and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States has shone a spotlight once again on the scourge of racism. In Ireland people who have been at the receiving end of racist attacks and racist attitudes have been speaking out.

On the right-wing fringes of politics racist groups and individuals have also been active, especially on social media. Like such groups elsewhere, they often use pseudo-patriotism to cloak their bigotry and try to hijack symbols such as the Tricolour and the Irish Republic banner which they have carried at rallies.

There is an attempt by some to create a type of ethno-nationalism here, something that has nothing to do with Irish Republicanism which, on the contrary, has been historically and is today inclusive, democratic and egalitarian.

In fact, opposition to racism goes back to the foundation of Republicanism in Ireland with the United Irish movement of the late 18th century. The whole basis of that movement was inclusivity, recognizing that the British Empire used religion and ethnicity to divide and conquer the people of Ireland, pitting Protestants of English and Scottish descent against Catholics of the Gaelic tradition. United Irish leader Wolfe Tone appealed for a definition of Irishness beyond religious labels.

And that vision went beyond Ireland. In

BY MÍCHEÁL Mac DONNCHA

the 1780s and ‘90s the town of Belfast was growing and prospering and among a section of the elite there was an effort to establish the slave trade there. The Atlantic slave trade was bringing enormous profits to the cities of Liverpool and Bristol. English merchants were sending ships to Africa where slaves were taken, sold at huge profit in America and the ships returned to England with goods such as cotton and sugar again to be sold at huge profit.

In 1786 the richest man in Belfast, and president of the chamber of commerce, Waddell Cunningham, proposed the establishment of a slave ship company in the city. A meeting of would-be slave traders was assembled but the opposition was led by Thomas McCabe, a Presbyterian businessman who stormed into the meeting and publicly tore up the plan.

The project went no further. McCabe went on to be one of the co-founders of the United Irishmen in Belfast in 1791, together with his brother William Putnam McCabe and others including Henry Joy McCracken. Henry Joy was executed after the United Irish Rising but his sister Mary Ann McCracken lived long after 1798 and campaigned against slavery, calling on people in Belfast to refuse to buy goods tainted with the blood of slaves.

A United Irish leader who had a direct and very unusual encounter with slavery was Edward Fitzgerald. As a youth he was a British Army officer in the American Revolutionary war and when wounded and left for dead on the battlefield he was rescued by a runaway slave, Tony Small. Small accepted Fitzgerald’s offer of a job as his servant, ensuring his departure from America and his freedom. They became close friends and Fitzgerald’s biographer Stella Tillyard says Small embodied and brought to life Fitzgerald’s “commitment to freedom and equality for all men.”

A veteran of 1798 and of Robert Emmet’s Rising of 1803 was Jemmy Hope the weaver from Templepatrick, Co. Antrim. He settled in Dublin’s Liberties and maintained his lifelong republican radicalism. In a poem entitled ‘Jefferson’s Daughter’ he condemned slavery in the United States:

When the incense that glows before

Liberty’s shrine

Is unmixed with the blood of the galled and oppressed,

Oh, then, and then only the boast may be thine

That the star-spangled banner is stainless and blest.

Like other white Americans, Irish-Americans in the middle of the 19th century were deeply divided on the issue of slavery and the rift between slave states and free states. Many Irish fought in the Civil War, most on the Union side, but many also

with the Confederates. Racism was rife in the North as well as the South and many Irish were prominent in opposition to the war and in violent attacks on African Americans.

In the most extreme case John Mitchel, the Young Ireland leader who had escaped from the British penal colony in Australia, was a vocal supporter of slavery. But others such as the Fenian John Boyle O’Reilly had a wider view of freedom, in keeping with the earlier United Irish tradition. He took over as the editor of the ‘The Pilot’ newspaper in Boston in 1871 and in an early editorial he deplored the opposition to integration expressed by a reader of whom O’Reilly wrote: “There is nothing Irish about his principles...’The Pilot’ holds that the colored man stands on a perfect equality with the white man”.

In a speech to a meeting of African-Americans in Boston in 1885 John Boyle O’Reilly described the racist segregation that he saw in the South:

“I was in Tennessee last spring and when I got out of the cars at Nashville I saw over the door ‘Colored people’s waiting room’. I went into it and found a wretched poorly furnished room crowded with men, women and children...I saw things that made me feel that something was wrong with God or humanity in the South and I said going away, ‘If ever the colored question comes

JOHN BOYLE O’REILLY, 1885

up again as long as I live, I shall be counted in with the black men.’”

He concluded his speech: “There is not among those who love justice and liberty any question of race, creed or color; every heart that beats for humanity beats with the oppressed.”

As a socialist and an internationalist James Connolly saw workers of all races and nationalities as equals. In his time as a trade union and socialist organiser in the United States he worked among immigrants from all over the world. In his newspaper ‘The Harp’ (January 1908) he addressed Irish workers in the USA on the issue of race:

“All races are mixed more or less; a pure race does not exist...The modern Irish race is a composite blending – on the original Celtic stock have been grafted shoots from all the adventurous races of the continent.”

In the ‘Workers Republic’ (July 1900) he made his position crystal clear:

“I rather like the intense desire to conserve the honour or freedom of a particular country, to which men have given the name ‘patriotism’. I am also a believer in the brotherhood of all men in the international solidarity of labour, and the identity of interests which everywhere link together the oppressed of the earth...”

Irish patriot Roger Casement exposed the enslavement by the rubber trade of millions of Africans and South American native peoples. He wrote in 1904: “The more we love our land and wish to help her people the more keenly we feel we cannot turn a deaf ear to suffering and injustice in any part of the world”. On the nation he wrote:

“And remember that a Nation is a very complex thing – it never does consist, it never has consisted of men of one blood or of one single race. It is like a river which rises far off in the hills and has many sources, many converging streams before it becomes one great stream.”

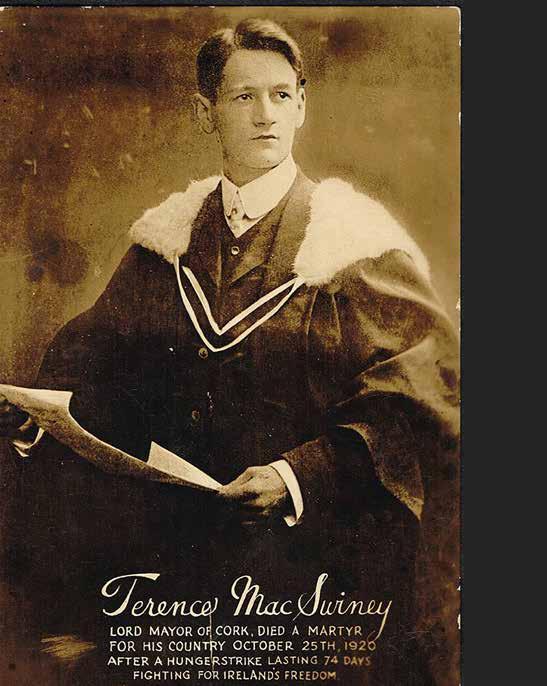

Two republicans who died 100 years ago also wrote words relevant to the struggle

Terence MacSwiney

against racism. In ‘Principles of Freedom’ Terence MacSwiney, Cork Lord Mayor and hunger strike martyr, wrote:

“If Ireland is to be regenerated we must have internal unity; if the world is to be regenerated, we must have world–wide unity – not of government, but of brotherhood. To this great end every individual has a duty and that the end may not be missed we must continually turn for the correction of our philosophy to reflecting on the common origin of the human race, on the beauty of the world that is the heritage of all, our common hopes and fears, and in the greatest sense the mutual interests of the peoples of the earth.”

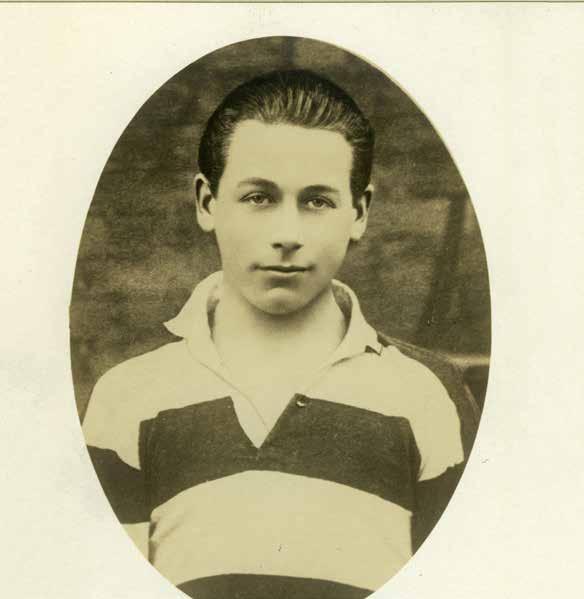

Terence MacSwiney and Kevin Barry died within days of each other in 1920. In an essay Kevin Barry wrote about racial prejudice: “It usually masks a much worse thing - oppression or tyranny. It is also divided into two classes, namely that of the white man against his coloured brother, for brother he is whether black, red, or yellow, and that of

the white man against his fellow-white man of a different nation. The two combined form the origin of very many of the world’s greatest wars and slaughter.”

Throughout the 20th century the development of Irish Republicanism ran parallel with anti-colonial struggles across the world. The anti-racist Civil Rights movement in the USA inspired our own Civil Rights movement, and liberation movements in Africa, Asia and Latin America, uniting people of all races, inspired the Irish freedom fighters of the 1970s and 1980s. To conclude this short historical survey of Irish voices against racism, the voice of Bobby Sands in his prison poem ‘The Rhythm of Time’:

It is found in every light of hope,

It knows no bounds nor space,

It has risen in red and black and white

It is there in every race.

It lights the dark of this prison cell It thunders forth its might, It is the undauntable thought my friend

That thought that says ‘I’m right’!’ •

Mícheál Mac Donncha is a Sinn Féin councillor in Dublin for the Donaghmede area