Portland, celebrating life

Anthroposophical Medicine

Anthroposophy & Contemporary Philosophy

Renewing the Foundation Year

The Foundation Stone Meditation

anthroposophy.org personal and cultural renewal in the 21st century a quarterly publication of the Anthroposophical Society in America fall issue - 2011

“A community to care for, celebrate and embrace the needs of those in their elder years”

Invites resident coworkers and their children to join our new community in beautiful rural Columbia County – with proximity to Hudson, Albany and the Berkshires.

Full benefits include: Housing, complete family medical package, Waldorf schooling, paid vacation, and the opportunity to be at the forefront of a new paradigm in elder care in this country.

Background in Anthroposophy and Camphill preferred. Please apply by email, along with any supporting documentation you may feel would be of interest.

Contact: Helen Wolff: wolffhelen@hotmail.com Please visit our website at www.camphillghent.org

FALL 2011

ANTHROPOSOPHY NYC

LECTURES, WORKSHOPS, ART EXHIBITS, FESTIVALS, STUDY GROUPS

RUDOLF STEINER BOOKSTORE

Works of Rudolf Steiner and many others Spiritual research, Waldorf education, personal growth, Goethean science, Biodynamic agriculture, holistic therapies, the arts, and more www.asnyc.org

Sept 9, Fri 7pm - Monthly Members Evening: Theme of the Year (also 10/7, 11/4, 12/2)

Sept 10, Sat 7pm - Eugene Schwartz: Auditioning For Antichrist, Pt 1/4: Setting the Stage, 1850-1900 (in 2012: Wilson 3/3, Hitler 4/14, Stalin 5/12)

Sept 14, Wed 7pm - David Anderson: Evolution of Religions in World History, Pt 1/10: Form Drawing (10/12 World Religions, 11/16 Ancient India, 12/14 Ancient Persia)

I believe that miso belongs to the highest class of medicines, those which help prevent disease and strengthen the body through continued usage. . . Some people speak of miso as a condiment, but miso brings out the flavor and nutritional value in all foods and helps the body to digest and assimilate whatever we eat. . .

—Dr. Shinichiro Akizuki, Director, St Francis Hospital, Nagasaki

—Dr. Shinichiro Akizuki, Director, St Francis Hospital, Nagasaki

Sept 17, Sat 1pm - Carole Johnson: Open Saturday: Nutrition & the Spirit, Pt 2 (Open Saturdays also 10/15, 11/19, 12/17)

Sept 26, Mon 7pm - Linda Larson: Eurythmy Workshop (also 10/24, 11/21, 12/12)

Oct 2, Sun 2pm - Michaelmas Festival: Community Pot-Luck Celebration with Music

Oct 16, Sun 1pm - Phoebe Alexander: Seasonal Painting, Fall Trees

Oct 21/22, Fri 7/Sat 10am–4pm - Mary Adams: “Welcome to the Dark Ages”: Star Knowledge in Urban Environment & in Spiritual Practice

Oct 27, Thu 7pm - Fred Dennehy: Georg Kühlewind Memorial Lecture

Nov 9, Wed 7pm - David Lowe: Leonardo, Michelangelo, & Raphael

Dec 9, Fri 7pm - Fred Dennehy & Dorothy Emmerson: A.R. Gurney’s Pulitzer-nominated play “Love Letters”

Dec 26 – Jan 6, 7pm - The Holy Nights

the New York Branch of the Anthroposophical Society in America 138 West 15th Street, NY, NY 10011 (212) 242-8945

centerpoint

www.southrivermiso.com WOOD-FIRED HAND-CRAFTED MISO Nourishing Life for the Human Spirit since 1979 unpasteurized probiotic certified organic SOUTH RIVER MISO COMPANY C onway , M assa C husetts 01341 • (413) 369-4057

From the Editors

Portland, Oregon, is said to be a very livable and forward-looking city. Our annual fall conference and members meeting is there (see page 41) and Leslie Loy, my collaborator on our E-News and a force in the Youth Section, shares her love of the city in words and pictures (page 6). We hope you’ll come, October 13-14 (youth events), 14-15 (conference), and 16th (members meeting). It’s more celebration of Rudolf Steiner’s 150th birthday!

We have two lengthy articles in this issue. Christopher Bamford, editor-in-chief of SteinerBooks, wrote a superb essay for the volume Introduction to Anthroposophic Medicine (see back cover). We’ve had little about health, and this illuminates that subject as well as key aspects of Steiner’s life, and that of his predecessor, Goethe (p. 10).

Yeshayahu Ben-Aharon (“Jesaiah” to his publisher) is a spiritual researcher of the most fundamental questions, including the nature of consciousness, the “knowledge drama” of our time, and the Christ’s return predicted by Rudolf Steiner. Yeshayahu is well able to stay abreast of current philosophy and the life of the mind, as Steiner did in his time, so we’re delighted to share a major lecture given in Alsace in 2007 (p. 19) bringing us up to date!

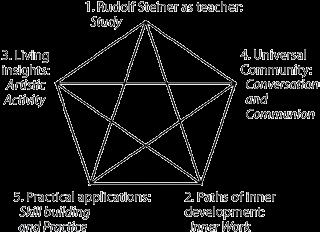

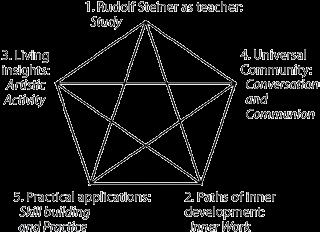

We “e-interviewed” Brian Gray about Rudolf Steiner College’s evolving Foundations in Anthroposophy which he directs. We share highlights on page 40, and the full text is online at anthroposophy.org (see Articles). — Rudolf Steiner’s “Foundation Stone Meditation” is featured in eurythmy at the Fall Conference; we share a perspicacious introduction and translation by the noted American poet Daisy Aldan (p. 44) to help you prepare for the conference. Or if you can’t be there in person, you might join in from afar by way of these reflections.

John Beck

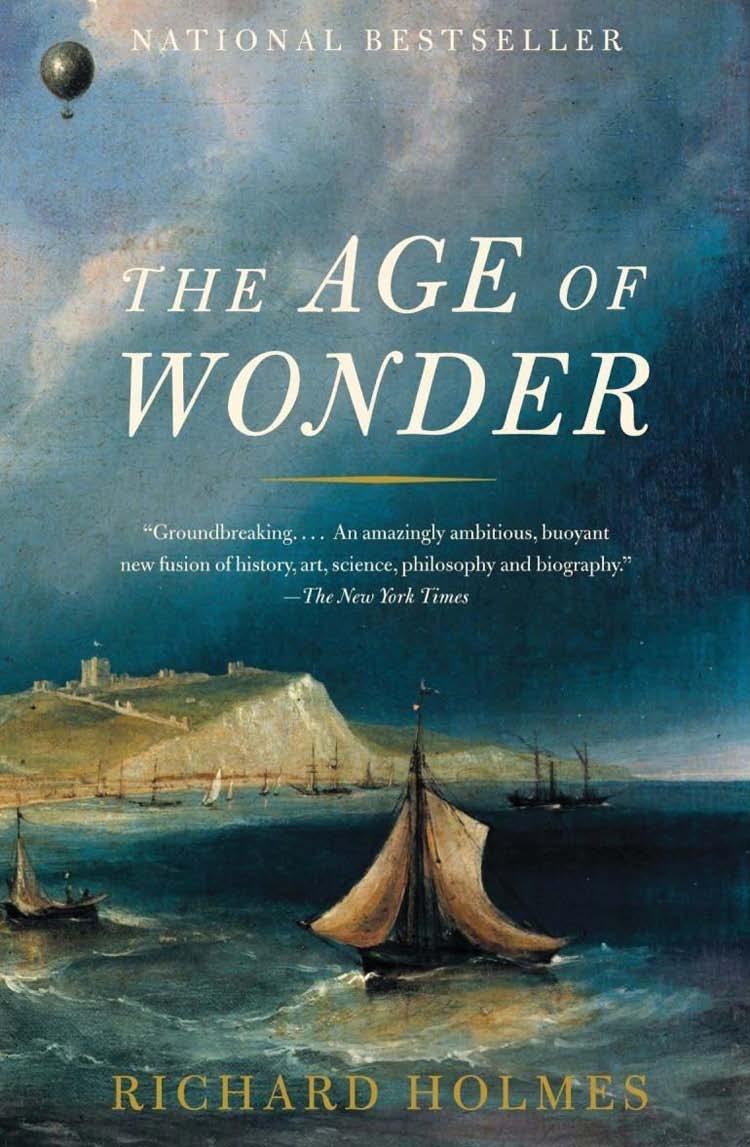

Both book reviews (pp. 34-39) from the Rudolf Steiner Library in this issue are concerned with history. I review The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science, by Richard Holmes, which tells the story of the development of science—the “second scientific revolution”—in the English Romantic period. Mr. Holmes’s book explores the development of science—often reflexively thought to be antithetical to Romanticism—during this time, and finds science and the Romantic movement to be intertwined in the wonder of discovery and hunger for what is new. According to Owen Barfield, Romanticism “come of age” is anthroposophy.

John Scott Legg, in his incisive review of The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, by Nicholas Carr, explores a more recent historical development: the effects of digital technology on our brains, our memories, and, especially, our changing notions of what it means to be human. While the narratives of the two books are obviously very different, taken together, they underscore how rapidly the popular conception of our humanity is changing, and call implicitly for a renewed understanding of our essential nature. We may hope that anthroposophy, with its improvisational and living capacity to meet the future, will contribute to that understanding.

The annotations (page 51) introduce a wide range of new books, including: Joseph Beuys: Parallel Processes, a large-format exhibition catalog; Initiative: A Rosicrucian Path of Leadership, by Torin M. Finser; A Modern Quest for the Spirit, by Ehrenfried Pfeiffer; The Guardian of the Threshold and the Philosophy of Freedom , by Sergei O. Prokofieff; and Life as Energy: Opening the Mind to a New Science of Life, by Alexis Mari Pietak.

How to receive being human, how to contribute, and how to advertise

Sample copies of being human are send to friends who contact us (see below). It is sent free to members of the Anthroposophical Society in America (visit anthroposophy.org/membership.html or call 734.662.9355).

To contribute articles or art please email editor@anthroposophy.org or write Editor, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48104. To advertise contact Cynthia Chelius at 734-662-9355 or email cynthia@anthroposophy.org.

fall issue 2011 • 3

Fred Dennehy

Being human, briefly noted

The Center for Biography and Social Art

Leah Walker has sent us two articles, now posted at anthroposophy.org under “Articles,” about a new “Center for Biography and Social Art” and its first event this spring, “The Magic of the Triptychon.” The center grows out of fourteen years of a program guided by Signe Schaefer and Patricia Rubano at Sunbridge. Leah writes, in part:

“Like many endeavors born of Rudolf Steiner’s teaching, biography work has developed relatively quietly for several decades. Now its role is growing, resonating with the needs of individuals and groups, and its strongly practical nature is coming to life: as a path for self-development and a vehicle for group process and progress; as a tool for healing relationships and building community; as a doorway into the great mysteries. Those of us vested in this spiritualscientific work have found ourselves immersed in a new art, social art, an art that illumines the sacred space between us. Through this work we shed light on our own unique unfolding and develop eyes and ears for the other, which is of real significance. And we come to recognize along the way, sometimes suddenly, that we tread the path of all humankind: in the life story of the individual we meet the universal...

“We know now that the Center for Biography and Social Art has been gestating for years within the hearts of those of us who love this work and we do love this work! We love the human being, the connection between people; we love social richness, conscious speaking and active listening; we love questions. The Center is a gathering of forces and resources, working from the inside out, radiating to communities and people in need. The ‘center’ also finds its existence at the periphery: the center is the individuals doing the work, being the rays themselves: social artists and community participants—all persons who engage actively in self- and social-development. The Center does not yet occupy a physical location, although one day it may. The thing is: social art happens in the world. It is practiced wherever people come together. The center for biography and social art exists where people gather, work, live, converse, struggle, grow—the center is human consciousness.

“To work with biography is to deepen one’s reverence for the life journey. The challenge of self-development is both wrenching and rewarding: can I take on a deep study of my life patterns, find meaning in the inherent intelligence of my biography, and take increasing responsibility for directing my life purposefully? ... Social art implies that a studio exists between people; indeed this will be increasingly the case, if we choose to treat it so. What a remarkable development it is: to understand that the human meeting is an artistic medium. As Goethe wrote, ‘What is more quickening than Light? Conversation!’ Our natural environment is human encounter, the social dynamic, where two or more are gathered. Clearly, the individual and the social environment are interdependent. But it’s not easy. We know all too well the difference between a light-filled conversation and one where light is absent. How do we work it out, this ‘individual life together’?”

To learn more about the Center for Biography and Social Art, please visit: biographysocialart.com , and direct inquiries to Kathleen Bowen at center4biography@gmail.com . And visit anthroposophy.org for the full articles describing the Center’s history, plans, and recent activity.

Elderberries Green Café

Excerpt of a post at the N. American Youth Section Facebook page:

“My name is Dottie Zold. I’ve been working with homeless youth, mostly from the Foster Care system for about 10 years now and mentally challenged adults. I opened a little café called Elderberries Green Café in the heart of Hollywood. It took me a year and a half to open and we opened on September 30th of last year. We are raw and also vegan and make our own cashew milks and almond milks in the morning as well as raw oatmeal and we are soon into sprouting. My coworkers are young people from an after school girls program that go to a school that is considered a last chance spot for the youth who have been kicked out of other places and mostly kids from the system. Our hope is to be a training spot for the kids from local homeless shelters so that they may learn a talent and then be able to apply for jobs that ask for experience. — Elderberries was not built for one. It was built to go across the country in the hopes to create spaces where young graduates of Waldorf and other like-minded youth, could work, further their education if they wished, and also create change in their communities.”

For much more to read of this great post, along with nice video links, scroll down at facebook.com/home. php?sk=group_189473471075203

Note

4 • being human

readers

& brief submissions for this page will be gratefully received! editor@anthroposophy.org Editor, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48104

to

Suggestions

6 Sensing a City’s Celebration of Life, by Leslie Loy 10 Introduction to Anthroposophical Medicine by Christopher Bamford 19 Anthroposophy & Contemporary Philosophy in Dialogue, by Yeshayahu Ben-Aharon 40 Renewing the Foundation Year, interview with Brian Gray 41 2011 Annual Conference & Members Meeting 44 The Foundation Stone Meditation by Rudolf Steiner translated with a preface by Daisy Aldan

eviews 34 The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, review by John Scott Legg 37 The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science, review by Frederick J. Dennehy

hresholds 51 New Members of the Anthroposophical Society News & e ve N ts 49 Threefold Research; WRC in San Diego; New Orleans’ 70th 51 Rudolf Steiner Library New Book Listings/Annotations

Contents Features

r

t

Portland, Oregon:

Sensing a City’s Celebration of Life

by Leslie Loy

by Leslie Loy

I don’t remember my first airplane ride into Portland—or if I got there by car. I do remember when I first smelled Portland: it was such an immediate sensorial reconnection with some inner part of my self. Portland smells green, it has a lushness to it. The very air invites me to sink my bare feet into the rich, temperate green grasses. I tried for days to describe how that luxuriant grass moved me. I knew it wasn’t about the color or the texture or the perfectly cooled air around it. Something had moved inside of me, catalyzed by the grass, and whatever that was lived freely in Portland. Later I would put it down to a cultural awakening: my European heritage melding with my American roots in a wonderful harmony.

6 • being human

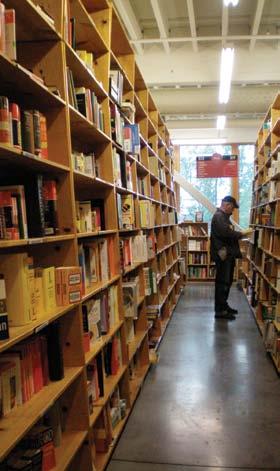

Only snippets remain of that first visit: reading a book on a park bench while friends played Frisbee; munching on a giant bowl of cherries and blueberries; sitting still in the Japanese Garden, watching the trickle of water in its creek; marveling at the individualistic bridges spanning the Willamette River. I recall endless rows of books at Powell’s; like a child’s my hand had to touch every spine, and my nose tickled with the smell of ink on paper. I watched the sunset from a friend’s studio apartment in the Pearl district, cold marble floors beneath my feet and the ceiling-to-floor window searing the palms of my hands, as the sound of jazz floated up from a club down the street. I remember thinking, Portland is magical.

When I realized that I wanted to call Portland my adult home, it began to live inside me. I never thought a city could do that. In Portland each block seemed different from the one before it—elegant and crisp or hip and expressionistic or simple and solid. Portland articulated itself so freely, it did its own thing so openly. Unabashedly it showed its jewels and its wounds and I appreciated that honesty. I never thought a city could do that, either.

I arrived to stay in early August 2006 with my car packed with boxes, books, and pictures—and my mother and sister in tow. The air was surprisingly humid and thick. Fans were running, and the entire world had slowed down. The neighborhood I moved into had rolling hills for streets, lined with giant trees that cooled the sizzling sidewalks. Children ran outside, their skins turning shades of brown and red, playing softball, soccer, blowing bubbles, selling homemade cards and lemonade; it was idyllic.

I wandered at first in a haze of marvel. A moment stands out in my first week, when I went to a yarn store on Hawthorne and discovered that this dainty little shop had gorgeous spools of wool and cotton to sell, and coffee and beer. I think I literally clapped for joy: What kind of a city sells beer at its craft shops? And so the love began.

Mind you, I am not a big fan of beer. No, I loved the fact that here people were clearly not afraid to be themselves. They could admit both to being crafty and to enjoying a good brew and could take pleasure in such a combination. That spoke to a part of myself that begged to be expressed and to be safe in its expression. That moment was a seed—of knowledge and of self.

Portland is a smart city, both in intellectual

competence and in general visioning capacities: before moving there, I learned that it was in the process of putting solar panels on low-income housing. Portland is filled with trees, ZipCars, buses, streetcars, train tracks, and bike lanes. It has long been a vibrant hub for the counter-culture which had been pushing the city since the 1970s to embrace the alternative and to thrive on it. Its indie music scene is as infamous as its roller derby; both thrive beside zine publishing and social activism.

I found myself bike-riding along river trails, visiting local farmers markets, taking the because it was easier, and delighting in the unexpected and the real. Sitting one night on the curb outside Ken’s Artisan Pizza off Pine in Southeast Portland, a glass of cool lemonade in my hand, I was admiring houses, clapboards with bright colors and wild gardens, when suddenly a man dressed in tuxedo and top hat rode by on a six-foot high bike. I chuckled and then laughed out loud at a woman riding behind the man dressed in miniskirt and fedora on a kid’s training bike.. So funny—and so real.

Or the birthday when I was riding in the elevator to the Portland City Grill, (spectacular cuisine, high atop one Portland’s tallest buildings). A tag on my lapel read, “Kiss Me, It’s My Birthday.” My friends had dressed me in a bright boa with bunny ears and I was grinning, no

fall issue 2011 • 7

Photos by Jennifer Bricker & Leslie Loy

doubt, from ear to ear, when the elderly gentlemen across from me, who was dressed to the T, suddenly leaned over and kissed me on the cheek. Startled, I demanded to know what he was doing, but he chortled and replied, “It’s your birthday!”

Portland is filled with unexpected surprises—even in elevators. Likewise, Portland But, more than that, the legends are not just histories, but are living stories or people who are part of the fundamental fabric of the city. Yes, Portland is relatively new to the scene, but it has its legends. (People love the stories of captains who, to kidnap sailors, would get them drunk in bars, and then throw them into the city’s underground “Shanghai” tunnels.) Historically, the city’s birth on a quiet resting spot along the banks of the Willamette came about because of three men, one coin and a common vision.

In the early 1840s, one William Overton decided to build a commercially-viable city at the junction of the Columbia and Wil-

lamette rivers. The natural resources of the area were astounding—fish, fur, wood, and rich green land—and he saw infinite potential. But Overton was flat broke, and so had to convince a Boston-based friend, Asa Lovejoy, to help him buy the land—all 640 acres of it. In the end, Overton’s contribution was a mere25 cents. Later, he sold his portion to a man named Francis Pennygrove in Portland, Maine. Pennygrove and Lovejoy couldn’t agree on what to name the city, so it was decided by a coin toss. Pennygrove won and he baptized the harbor town Portland after his hometown. It’s a good story, and it also sets a tone for the biography of Portland.

Portland appreciates life. As a result, life is everywhere. Early mornings from mid-March until late Fall, the rivers are dotted with crews of rowers dipping oars into the shimmering water, while joggers, bikers, and dogs run on the shore banks. One of my favorite sights as I traveled to work in downtown Portland was these mornings along the rivers.

In the middle of a busy workday, Portlanders downtown meander to Pioneer Square. They hustle like all city-dwellers, but they also lounge a lot, enjoying the scenery. The Square offers music, laughter, the occasional bum, dogs running back and forth, even sometimes a llama or two.

I recall sitting back on the white Adirondack chairs scattered on the red brick of the Square, watching hip-hop and break dancers, while groups of teen-

8 • being human Caption

agers offered free hugs to any willing passerby. Tourists munched on Voodoo donuts or steaming piles of Pad Thai. Businesswomen slid off their heels and took a few minutes to sunbathe on the steps. Often, I would peer into booths at multicultural fairs or feel the vibrations of a radio festival. The best time in the Square, however, is when the entire block becomes a garden with hundreds or thousands of potted flowers and bushes transforming its brick floor into a blossoming heaven.

Portland’s setting is magical. A little over an hour in any direction lands you in different kind of nature: desert, mountains, beach, the river. The people are notoriously progressive and hardcore: snow, rain, wind, sunshine, hail, even sleet cannot keep them from their business. Bicyclists race the roads at any hour, in any kind of weather, in all kinds of attire: quintessential Portland.

A couple of years ago, Business Week released a survey that claimed that Portland was the Unhappiest City in the country. People were furious ! I couldn’t understand that conclusion either. I saw abundant creativity, joy, ingenuity. I saw caring, compassion, celebration.

American author M.F.K. Fisher once wrote: “Sharing food with another human being is an intimate act that should not be indulged in lightly.” Portlanders live life through food—it is how friends come together, how heartbreak is healed, how benchmarks are celebrated. People meet over Stumptown coffee, mouthwatering cakes, almond croissants, frog legs and alligator jambalaya, vegan donuts, mason jars of sweet tea, or chilled glasses of frothing beer. They love farmers markets with their sumptuous cheeses, flowers, fruit, breads and exotic spreads—all local, all fresh, all gorgeous. Restaurants harmonize simplicity with affordability to tantalize the palette. There is, for example, the Whole Bowl, which has mastered the art of one simple dish–there’s nothing else on the menu–brown rice with red and black beans, decked with fresh avocado and “trace amounts of attitude.”

Food, art, and the outdoors are all creative outlets inspired by the scenery. This is what drew me to Portland. I wanted to live in a place

where adults had imagination and weren’t afraid to express it: I wanted to be surrounded by people who celebrated life through all of their senses—and expressed it as smart, sassy, creative, wild, appreciative, present. There’s something clearly alive in Portland, and it continues to evolve and sustain us. The stories engage, the sights inspire, and the people are open.

Portland offers the best of city life without much less grime and traffic. Its diversity (impoverished and superbly wealthy communities, mom-and-pops and the box stores, the quirky and the banal) feels to me like a celebration of life. Nature is honored, spirituality is respected. It is not only a city where sky and skyscraper meet, it is the city of my dreams, where river and rower move together and where the future is beckoning with light and great anticipation.

In

Portland?

here are some great locales to enjoy:

Food Papa haydn’s the Carts

Fong wong’s dim sum the delta lounge

Mother’s Bistro

voodoo donuts

Sights Powell’s Books Japanese Garden rose Garden the Grotto hawthorne avenue

saturday Market

Explore the willamette trail sauvie island

willamette Falls riverfront

fall issue 2011 • 9

Introduction to Anthroposophical Medicine

by Christopher Bamford

After the First World War, and indeed presciently, as it was already drawing to a close, in response to the widespread social-political chaos and the sense of profound psycho-spiritual and cultural rupture—civilization ending—Rudolf Steiner felt impelled to become outwardly and socially engaged in a new way. There were powerful practical reasons to do so. The collapse of the old social order made it seem possible to reorganize social, economic, and cultural life according to human reality and spiritual principles. There were compelling esoteric reasons, too. Above all, the moment was right. Cosmic and spiritual circumstances made it possible (even necessary) to infuse initiatory and mystery wisdom into the germination process of the coming civilization. The future evolution of humanity in some sense depended on it.

Thus, from 1918 onward, new initiatives flowed out of anthroposophy into the world: first, the Movement for Social Renewal or “The Threefolding of the Social Organism” (1918), followed a year later by the founding of the first Waldorf School in Stuttgart (1919). Then, in 1920 businesses were founded and, most importantly, a major effort was made to refound the various disciplines of learning, the arts and humanities as well as the sciences, out of anthroposophical insight and research. At the head of Rudolf Steiner’s list of sciences (and professions) potentially receptive to such insight and research stood medicine. This was a field of longstanding and passionate interest, with which he had always hoped to work.

At the beginning of the year, on January 6, as the second of three public lectures in Basel, Switzerland, on the topic “Spiritual Science and the Tasks of the Present,” Steiner gave a talk titled “The Spiritual-Scientific Foundations of Physical and Psychological Health.”

He stressed that while practitioners of modern science strive to exclude the human being from their picture of the world, to remove themselves from it and be as value-free and objective as possible in their concepts, anthroposophical spiritual science always strives to be holistic, moving from the wholeness of the healthy human

being to the wholeness of the cosmos into which it is integrated and out of which it is organized. The field of spiritual science thus encompasses our whole being and is able to investigate the complex and continually metamorphosing relationships and connections between our soul-spiritual and physical aspects. He then turned to medicine, which most clearly demonstrates the “disadvantages” of the natural scientific approach for “it is the most striking example of what happens when science eliminates the human being from its methods.”

Mere intellectual knowledge of the laws of aesthetics does not make you an artist. By the same token, simply knowing the current natural laws does not make a person a healer. Physicians must be able to live in the activities, the ebb and flow of nature, with their whole being. They have to be able to immerse themselves completely in creative, weaving nature. Only then will they be able to follow with sincere, heartfelt interest the natural processes accompanying illness. At the same time, studying healthy people will help physicians to understand them when they are ill.

After alluding to some spiritual-scientific insights— such as the threefold thinking, feeling, and willing human being mirrored in the sensory-nervous, respiratoryrhythmic-circulatory, and metabolic systems—Steiner then concludes:

Precisely when it comes to such an area as truly intuitive medicine, it would be the spiritual scientist’s ideal to be able to speak before those who are specialists in the field. If they could find their way in and allow their expertise to speak without preconceptions, they would see how much spiritual science could enrich their specialty. Spiritual science, which is no unprofessional dilettantism, does not fear criticism from experts. It seeks to create deeper scientific sources than those of today’s conventional science and it knows that amateurism, not

10 • being human

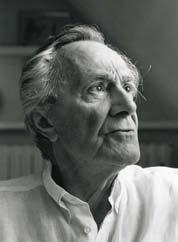

Christopher Bamford

expertise, is what it might have to fear—had it not long since overcome fear for reasons that are easily understood. Spiritual science has nothing to fear from expertise or lack of preconceptions. It knows that the more expertise is brought to bear on its findings, the more positively they will be accepted. In considering what might be a perspective for an intuitive medicine, we might remember an old saying ... [which] in a narrower sense is certainly applicable to the art of treating the sick human being. Wise folk of old said, “Like is known only by like.” To heal human beings one must first know them. The part of the human being with which science today concerns itself is not the whole human being. When the whole human being is called to know the human being, then will like (a human being) be known by like (another human being). Only then will a human knowledge of the human being and a healing art arise that will, on the one hand, keep the human being as healthy as is possible in his or her social life and, on the other, treat illness in a way that is possible only if all the actual healing factors are considered together.

Clearly Steiner was issuing a challenge, or at least a call; but it was not one that was taken up by any of the physicians present. In fact, only a chemical engineer, Oskar Schmiedel, heard it. Acting on what he heard, Oskar Schmiedel organized the first course in anthroposophical medicine. As he himself noted, this fact made anthroposophical medicine very different from all other anthroposophical initiatives (like eurythmy, Waldorf education, The Christian Community, and biodynamic agriculture), which without exception were undertaken by Rudolf Steiner in response to specific requests. Schmiedel wrote:

The first doctor’s course was not given at the request of doctors or medical students, or in fact on the basis of any request at all. The reason why Dr. Steiner departed from custom probably has to do with the fact that he thought it important and timely to speak about medical questions without waiting for doctors to approach him with the request for such a course. Furthermore, this first doctors’ course proved how much he could offer the doctors. Everyone attending the course felt something like the opening of the floodgates. The future was to show how important it was that the course was held at just this time. Preconditions were thus achieved that made it possible to start Dr. Wegman’s Clinical-Therapeutic Institute in Arlesheim, as well as the one in Stuttgart. My own role was simply to create the outer conditions that en-

abled Rudolf Steiner to give the lectures he wanted to give. (Italics added)

Given the dire economic conditions in Germany, Schmiedel spent the months preceding the course organizing lectures and collecting money to make it possible for German physicians to come to Dornach. He also organized the course itself, which unfolded under beautiful spring weather. More than thirty doctors and medical students attended. Steiner was very strict about admission: he would allow only professionals. Otherwise, he said, he would have to give entirely different lectures. Natural healers, midwives, nurses, and even a Russian medical officer were banned. Only three exceptions were made (Marie Steiner, Walter Johannes Stein, and Roman Boos), and Steiner was apologetic about them! The course itself was a great success. Planned to comprise two weeks, at the request of the participants it was extended to three. Steiner lectured in the morning, and either he or someone else gave the evening lecture. At the same time as the medical course, another course, “Anthroposophy and the Various Branches of Science,” was taking place. During this same period, a theology student from Basel, Gertrud Spörri, came to ask Steiner whether it would be possible to create an anthroposophically oriented movement of renewal within the church. Steiner replied that he would speak to young people on that topic quite differently than he spoke to the doctors, as in fact he did when a year later he gave the first theology course for priests. All of which is to say that things were moving very fast at this time.

The medical course, however, stands apart. The organization of the course was interactive and to some extent spontaneous. Steiner had a general program of what he wanted to accomplish, but within it he left himself open to improvisation based on the needs and questions of his audience. Before beginning, he asked those assembled to jot down specific wishes and submit them. He then undertook to integrate his responses with their requests as the lectures unfolded. Consequently, these lectures have the aliveness and excitement of a dialogue: the sense of dealing with living concerns, not theory. Another important consequence is that the course achieves a fullness, even as Steiner himself says, a “sort of completeness,” unusual in such an “introductory” presentation. So much is covered: the meaning of sickness; the history of medicine; polarities in the human organism, in the cosmos, and in nature; the heart; the three systems (nervous, rhythmic,

fall issue 2011 • 11

Those attending the course felt something like the opening of the floodgates.

and metabolic); nature outside and nature within the human organism; soul, spirit, and body; diagnosis and the whole person; mineral, mercurial, and phosphoric processes; the therapeutic use of metals; the senses; homeopathy—the list is wellnigh endless.

As Schmiedel noted: Everyone attending the course felt something like the opening of the floodgates. Readers of this book, Introduction to Anthroposophical Medicine, will confirm for themselves how right he was. It is as if Rudolf Steiner had been waiting for the opportunity to engage these subjects: to talk to doctors, to address their concerns our of spiritual science, but in the language of medicine and healing. Rarely has he seemed so at home in his subject, so familiar with it, so passionate about it. Rarely, too, has he seemed to have so much enjoyment in giving a lecture course, feeling so much pleasure at being able to layout a series of overlapping perspectives in the certainty of being understood. It is as if, here, he felt himself to be among those with whom he was completely at ease.

Though not a physician by training, as he stressed in his lectures, Rudolf Steiner’s medical interests were clearly longstanding, deep, sophisticated, diverse, and far-reaching. A scientific education at the Technische Hochschüle in Vienna (the M.I.T. of its time), coupled with a lifelong passion for learning (reading all the latest books meant that his knowledge of many fields— including mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, anatomy, zoology, botany, and geology—was always detailed, professional, and up-to-date. Justifiably, therefore, he has been called a “Renaissance man.” There are few disciplines of which he was not master from his own, special point of view. But medicine—healing—holds a special place in his biography and mission. Examining it will provide a background to the founding lectures of anthroposophical medicine collected here.

It must be said that the combination of the range and depth of Steiner’s knowledge often seems hard to believe. Certainly, in many ways it was unique. To begin to understand it, we must imagine a person who, from a very early age, was single-mindedly dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge and understanding of the human condition, and used every available opportunity to deepen, test, and enrich his worldview. However, we must not imag-

ine a person interested only in abstract or theoretical knowledge, or knowledge for its own sake. Rudolf Steiner’s search for knowledge was always practical and existential. He sought to know because he wanted to act consciously and freely out of the truth of what it meant to be a human being. He did so in order to make human life truly and profoundly conformed to reality in all its details. In other words, he was a “detail” person for whom—as it was for Goethe before him—the phenomenon, that is, the given fact, must in the last analysis be the theory. For him, theory must be immanent in experience, not something super-added to it. At school, his interests were threefold and interrelated. He loved geometry and mathematics, and was always deeply interested in what he could discover in the sciences, especially physics, chemistry, and astronomy. What united this diversity (and led to what we might call a “sub-interest” in world history and the evolution of consciousness) was a passion for thinking itself, for posing questions whose answers he would try to discover for himself through a disciplined process of meditation and study. Thinking for him was not a limited, skull-bound, private activity, but the essential human experience by which a person could begin to participate in those cosmic processes whose traces the various sciences try to parse and formalize. Thus, in parallel with his school courses, from adolescence on, he began to read what he could of philosophy, above all the German Idealist tradition of Kant, Hegel, and Schelling, whose influences could be felt everywhere in his environment. Thus, he struggled with the great questions, such as: Are there limits to knowledge? What are space and time? What is matter? What is life? What is light?

Three signal, life-altering extracurricular events, really the three major influences in his life—which would not only prepare him for his later role as spiritual teacher and anthroposophist, but also orient him, at least implicitly, toward medicine and healing—occurred shortly after Steiner entered the Hochschüle.

Officially, during his first year he was registered for classes in mathematics, natural history, and chemistry, Unofficially, he also attended other lectures and read deeply and widely in the library. Continuing his interest in philosophy, he attended lectures by the now-forgotten Robert Zimmermann and the still-celebrated Franz

12 • being human

To understand the range and depth of Steiner’s knowledge, we must imagine a person dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge and understanding of the human condition...

Brentano (who was Husserl’s teacher, taught the only philosophy course Freud ever took, and inspired Martin Heidegger to investigate Aristotle’s theory of being.) Most significant, however, was a course offered by the literary scholar Karl Julius Schröer on Goethe and Schiller and, what we might call, the consequences of Romanticism in German thought. Steiner and Schröer became very close. Steiner read Goethe’s works (Faust 1 and 2) for the first time and passed many memorable evenings talking about Goethe with Schröer. As Steiner writes: “Whenever I was alone with Schröer, I always felt a third was present—the spirit of Goethe.”

Schröer, however, knew little about Goethe’s science. At first, Steiner likewise had little interest in it. He was more interested, as he says, “in trying to understand optics as explained by physicists.” Trying to do so, however, was sheer agony for him. Physicists understood light as vibration and colors as specific vibrations, but Steiner intuitively understood light as an extrasensory reality experienced within the sensory world that revealed itself as color. Such thoughts prepared him for the task that would come to him through Schröer when, in 1882, on his teacher’s recommendation, Steiner was asked to edit Goethe’s scientific writings for a collected edition, adding his own introductions and explanatory notes.

Encountering Goethe’s work (in honor of whom he would name the new mystery center of anthroposophy the “Goetheanum”) and spending more than fifteen years studying it intensely was certainly life-confirming and life-altering in many ways. Above all, we may say that it introduced Steiner to the alchemical Hermetic tradition, itself the growing tip or germ of that sacred science of the ancient Mysteries that Steiner would bring to modern consciousness and contemporary fruition in anthroposophy. For Goethe, the great opponent of Cartesian-Newtonian mechanicomaterialism, did not come to his scientific views unaided. He was, as R. D. Gray showed in his Goethe the Alchemist “profoundly influenced throughout his life by the religious and philosophical beliefs he derived from his early study of alchemy.” Goethe’s science in essence was alchemical and Hermetic.

Goethe was not alone in his interests, though he alone by his genius made a science out of them. In his era, the study of alchemy was still widespread; many people had

alchemical laboratories. Alchemical language and philosophy, deriving from Jacob Boehme and Gottfried Arnold, had become part of the then-dominant spiritual revival called Pietism. Indeed, it was a Pietist friend of Goethe’s mother’s, Katerina von Klettenburg, who introduced him to alchemy during a severe illness at nineteen when he had a tumor in his neck, which could have been fatal.

As Goethe describes her, Katerina was an extraordinary woman: “a beautiful soul,” that is to say, serene, graceful, patient, accepting of life’s vicissitudes, intelligent, intuitive, imaginative, and above all a moral and religious genius. In their meeting, one genius discovered another. “She found in me,” Goethe writes, “what she needed, a lively young creature, striving after an unknown happiness, who, although he could not think himself an extraordinary sinner, yet found himself in no comfortable condition, and was perfectly healthy neither in body nor in soul.”

Katerina provided medical assistance in both body and soul. She found him a doctor, Dr. Metz, who prescribed, in addition the conventional remedies of the time, some “mysterious medicines prepared by himself of which no one could speak, since physicians were strictly prohibited from making up their own prescriptions.” These medicines included “certain powders” as well as a “powerful salt”—”a universal medicine.” To encourage their efficaciousness, Dr. Metz further recommended “certain chemical-alchemical books to his patients ... to excite and strengthen their faith,” and to encourage them to attain the practice of making the medicines for themselves.

Thus, as Goethe convalesced he and Fraulein von Klettenburg began an intensive study of certain texts: above all, Paracelsus, Basil Valentine, Eirenaeus Philalethes (George Starkey), Georg von Welling’s Opus Mago-Cabbalisticum et Theosophicum, van Helmont, and the Aurea Catena Homeri (The Golden Chain of Homer). At the same time, Goethe began laboratory work.

Goethe’s alchemical work continued intensely for the next few years. He continued to study alchemical and Rosicrucian authors. Two years later, he still claimed “chemistry” was his “secret love.” As he wrote to his mentor E.T. Langer: “I am trying surreptitiously to acquire some small literary knowledge of the great books, which the learned mob half marvels at, half ridi-

fall issue 2011 • 13

Steiner intuitively understood light as an extrasensory reality experienced within the sensory world...

cules, because it does not understand them, but whose secrets the wise man of sensitive feeling delights to fathom. Dear Langer, it is truly a great joy when one is young and has perceived the insufficiency of the greater part of learning, to come across such treasures. Oh, it is a long chain indeed from the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus.... “ For a time, his alchemical studies occupied Goethe completely. In fact, until he met the cultural genius Herder and turned to more “acceptable” studies, they dominated him almost obsessively. As he writes, “My mystical-religious chemical pursuits led me into shadowy regions, and I was ignorant for the most part of what had been going on in the literary world at large for some years past.”

Here a brief aside on the four-stage history of medicine—Greek, Monastic, Paracelsian, and Romantic—may be useful. The point is threefold. First, it was these studies that determined Goethe’s worldview and especially his science, which is alchemy translated. Second, these “mystical-religious chemical pursuits” that provided the ground for an anti-materialist, living approach to nature and natural processes differed fundamentally from ordinary, “value-free,” quasiobjective science in that their raison d’être was clearly to heal: to serve humanity. Many alchemical texts, in fact, were explicitly “medical” in orientation. Unfolding an alternative science, they also provided a theoretical and practical model for an approach to medicine. Third, in order for Steiner to understand Goethe and “translate” his worldview and epistemology for the last third of the nineteenth century Steiner would necessarily have had to study the Paracelsian and other alchemical-medical works that Goethe studied. Therefore Rudolf Steiner’s encounter with alchemical medicine—represented by Paracelsus, Basil Valentine, and the Rosicrucians—began very early and was very deep, fired by the ambition and the intensity that his work with Goethe required.

Ancient Greek medicine, transmitted by Hippocrates, Aristotelianized, cast in stone by Galen (much in the same way as Euclid petrified Pythagoreanism), and passing through Islam (and Avicenna), reached the Middle Ages, where it in turn soon ossified. In parallel, through the triple confluence of traditional Western herbal knowledge, the transmission of alchemy from Islam, and esoteric Christianity, what we might call “mo -

nastic medicine” arose. The medical texts of Hildegard of Bingen and Albertus Magnus, for example, give some idea of what this meant. The Renaissance then witnessed the overthrow of the ruling medical paradigm, which, despite monastic medicine and the growing presence of alchemical approaches, was still based on Aristotle, Galen, and Avicenna.

The revolution came through the turn to experience. Through anatomy and dissection certainly, but most significantly the Paracelsian synthesis that combined the fruits of monastic and folk culture with the newly available Hermetic, Neoplatonic, and gnostic insights, and the flowering of Christianized alchemy in a new, nature-based, experiential, existential spiritual science. Paracelsus’s influence was tremendous and continued through the end of eighteenth century, when Hahnemann reformulated certain aspects of it as homeopathy. Hahnemann was, however, only one of those attempting to create what we might call “Romantic” medicine, a living medicine, a medicine of life, that would be the practical enactment of a true philosophy of nature (Naturphilosophie). At the heart of the Romantic moment—say 1770 to 1830—was an attempt to put medicine as the science of life at the heart of a general reformation such as the Rosicrucians had first announced. Such was the tip of the iceberg that Goethe’s work presented Steiner.

In addition to his life-altering encounter with the works of Goethe, two other—yet strangely related—lifealtering encounters helped form Rudolf Steiner’s basic orientation. First, there was a meeting with a nature-initiate, a factory worker and herb gatherer, Felix Kogutski, “a simple man of the people.”

Once a week he was on the train that I rook to Vienna. He gathered medicinal plants in the country and sold them to pharmacies in Vienna. We became friends and it was possible to speak of the spiritual world with him as with someone of experience. He was deeply pious and uneducated in the usual sense of the word ... With him, one could look deeply into the secrets of nature. He carried on his back a bundle of healing herbs; in his heart, however, he carried the results of what he had gained from nature’s spirit while gathering them .... Gradually, it seemed as though I were in the company of a soul from ancient times .... One could learn nothing from this man in the usual sense of the world. But through him, and with

14 • being human

At the heart of the Romantic moment was an attempt to put medicine as the science of life at the heart of a general reformation such as the Rosicrucians had first announced.

one’s own powers of perception of the spiritual world, one could gain significant glimpses into that world where this man had a firm footing.

The meeting with Felix Kogutski, important as it was, was only preparatory to an even more significant encounter with the figure Steiner refers to only obliquely— in his autobiographical notes for Edouard Schuré—as the M. (or the Master). As Steiner puts it “... Then came my acquaintance with the agent of the M. ... I did not meet the M. immediately, but first an emissary who was completely initiated into the secrets of plants and their effects, and into their interconnection with the cosmos and human nature....”

While the Master’s identity must remain to some extent conjecture, it is nevertheless dear from Steiner’s own indications that the teacher in question was Christian Rosenkreutz, the founder and guiding spirit of the Rosicrucians. However redolent of charlatanism the word “Rosicrucianism” may sound today, given how many different groups and persons have often evoked it for less than reputable purposes, in this instance it must be taken seriously.

Rosicrucianism first burst—there is no other word for it—onto the scene of history in the early seventeenth century with three surprisingly widely distributed texts, originating in Lutheran circles in Tübingen, Germany, and published sequentially in Kassel in 1614, 1615, and 1616. The first two texts—the Announcement of the Order (Fama Fraternitatis) and the Confession of the Order (Confessio Fraternitatis)—told the story of Christian Rosenkreutz (1378-1484) who, some two hundred years previously, had traveled the world in search of spiritual, scientific, and universal wisdom before returning home to Germany, where he gathered students around him and formed an order. The time was, however, not yet propitious for public work and so he decreed that, following his death, his mission and teaching were to remain hidden for one hundred and twenty years—that is, until 1604, the legendary date given for the opening of his tomb. The third text, The Chemical Wedding, an alchemical allegory of spiritual development, was obviously different in tone, but served the same purpose: to proclaim a “general reformation” of science, art, and religion, a revolutionary program of cultural transformation based on raising into modern

consciousness and thoroughly “enchristing” the entire harvest of ancient and traditional mystery wisdom. The manifestos called for all like-minded people to join the movement. A furore —literally, frenzy—resulted. Paracelsian physicians, philosophers, alchemists, artists, and scientists from all over Europe began writing tracts and treatises to qualify them to join the movement. But no one knew who the Rosicrucians were, or where to find them! Chaos ensued. Reactionary and repressive forces from the church and materialist science arose to quell the revolt—unsuccessfully at first, but within a few years, what they were unable to do, the Thirty Years War (1620-1650) accomplished very efficiently, and the Rosicrucians disappeared from the exoteric world.

Rosicrucianism as a historical and cultural impulse is important for Steiner’s approach to medicine above all in three ways. First, we may note the “rules” of the original brotherhood: First, to profess no other thing than to heal the sick, and that gratis. — In other words, the primary orientation of the Rosicrucian is toward healing as an act of service. We may call this the rule of love or compassion, which, as Paracelsus wrote, is “the true physician’s teacher.” As service, it also implies an orientation toward the world— toward other beings, for we can love only other living beings—as well as the dedication to work selflessly and compassionately for world evolution. The Rosicrucian thus works for the sake of the world and from this point of view sees no difference between the healing of soul and body and the healing of the world. This dedication to heal affirms the primacy of action. If one is a true Rosicrucian, one walks, as Rudolf Steiner walked, “the true thorn-strewn way of the Cross,” renouncing all egotism for the sake of the healing of the world.

Second, to wear no kind of special habit, but to follow always the custom of the country in their dress. — At its simplest, this second injunction has been taken to mean that Rosicrucians were called to live anonymously, unpretentiously, plying some ordinary trade. But at another, higher level, since chief among the customs of a country is its language, the rule invokes the “gift of tongues,” possession of which enables one to address people in their own language, that is, in the way and at the level appropriate to their understanding. This implies, too, that a Rosicru-

fall issue 2011 • 15

The Rosicrucian works for the sake of the world and sees no difference between healing of soul and body and healing of the world.

cian is attached to no form or dogmatic belief and is able to translate wisdom into any form as circumstances may require. Rudolf Steiner’s adherence to this second “rule” is manifest in his task and vocation—in fact, his “commission,” for his encounter with the M. directly led to it—of adapting or translating (that is, restating on the basis of his own experience) Rosicrucian-alchemical wisdom into a form appropriate to modern scientific consciousness.

Third, to meet together at the house Sancti Spiritus every year at Christmas. — This rule affirms the primacy of communion in the spirit and of the unity of humanity through participation in the spirit.

Fourth, to seek a worthy person to succeed them after they die. — That is, to teach, to create a lineage of friends.

Fifth, to make R. C. “their seal, mark, and character.” — In other words, to have the Rose Cross, the union of love and knowledge, inscribed in their hearts, which is to say that to conjoin the Rose and the Cross, love and knowledge, in nature and human nature as one, to heal and unite nature and human nature in its center or heart, is the goal of the Rosicrucian work. (To complete the “rules,” the sixth and final rule specified that these rules were to “remain secret for one hundred years” [more precisely, 120 years] after Christian Rosenkreutz’s death.

The second way in which Steiner’s Rosicrucian calling significantly determined his approach to medicine was the central role accorded Paracelsus in Rosicrucian lore. The Fama mentions him as a forerunner who, “though he did not enter our Fraternity,” read carefully in the Book of Nature with great effect, failing however to bring about the revolution he desired because of his irascible temperament. Nevertheless, not surprisingly, his books were held in such high esteem that he is the only author mentioned by name as having his works stored for continual study in Christian Rosenkreutz’s tomb. This Paracelsian emphasis carried two further associations, namely: the primacy of medicine (in the original documents paired with theology)

and the importance of alchemy and its “universal medicine,” despite the cheaters and quacks who confuse it with the search for material gold.

All these elements (Rosicrucian, Paracelsian, and alchemical), which are really one universal approach, contributed significantly to Rudolf Steiner’s understanding of the ethics, philosophy, and practice of medicine and the art of healing, which may therefore be called “Rosicrucian-Paracelsian-alchemical.” More generally, since this tradition is, in fact, heir to the entire Western mystery tradition, whose source, finally, as Steiner will repeatedly stress, is the ancient mysteries themselves, we may call what Rudolf Steiner brought into the world as anthroposophical medicine “traditional Western medicine” in the same sense that we speak of traditional Tibetan or Chinese medicine—but spoken anew out of contemporary experience and consciousness.

From the beginning of his professional career as a Goetheanist, philosopher, and man of letters, this tradition was thus Steiner’s constant, if hidden, companion and study. It accompanied him as he wrote his books on, and introductions to Goethe, and as he hammered out an epistemology or theory of knowing appropriate to contemporary consciousness, one that could legitimize what we might call a “Paracelsian” approach to nature. It was not his task—nor was he yet ready—during this first period of his life to bring it into the open. For that, he had to wait until he had reached the necessary maturity (forty years of age) to stand forth as a spiritual teacher. Then, in 1900, as if foreordained, the opportunity arose when he was asked to give a course of lectures in the Theosophical Library in Berlin. “By means of the ideas of the mystics from Meister Eckhart to Jacob Boehme,” he wrote later, “I found expression for the spiritual perceptions that in reality I decided to set forth. I then summarized the series in the book Mystics after Modernism.” It was an important moment. As Paul Allen, in his introduction, puts it, “This book is significant in the life-work of Rudolf Steiner because it is a first result of his decision to speak out in a direction not immediately apparent in his earlier, philosophical writings.”

For our purposes, the key chapter, which comes after three more or less epistemological chapters, is chapter 4: ‘’Agrippa von Nettesheim and Theophrastus Paracelsus.” Here Steiner shows that what the “mystics” Meister Eckhart, Johannes Tauler, Heinrich Suso, Jan Ruysbroek, and Nicholas of Cusa worked out as a way of thinking or path of consciousness, Agrippa first more tentatively and

16 • being human

We may call what Rudolf Steiner brought into the world “traditional Western medicine” in the same sense that we speak of traditional Tibetan or Chinese medicine— but spoken anew out of contemporary experience and consciousness.

then Paracelsus more fully and thoroughly put into action as a “natural science” to the extent possible within the limits of their times: a new way of knowing and working with nature.

Steiner shows how Paracelsus, taking a stand on himself, on experience, seeks to ascend through his own cognitive powers to the highest regions. He does not want to accept any authorities, but to read directly in the Book of Nature for himself. But this does not come without a struggle, for he is faced by the mystery of human experience that feels itself the apex of, and woven into, universal nature, and yet is hindered from realizing the relation because one experiences oneself as a single individual, separate from the whole. Paracelsus understands that in the human being what is a reality within the whole feels itself a single, solitary being. Thus he knows he experiences himself at first as something other than he is. In other words: we are the world, but we experience our relation with the world as a duality. We are the same as the world, but as a repetition of it, as a separate being. Such for Paracelsus is the paradoxical relationship of microcosm and macrocosm.

Steiner goes on to explain that Paracelsus calls what causes us to see the world in this way our “spirit.” This seems singular, individual: a repetition bound to a single organism. While the organism is part of the great chain of the universe, its spirit seems connected only to itself. The struggle is to overcome this illusion.

In reality our nature falls into three parts: our sensory-bodily nature as an organism; our hidden nature, which is a link in the chain of the whole world and is not enclosed within the organism, but lives in relation with the whole universe; and our highest nature, which lives spiritually. The first he calls the “elemental body”; the second, the “astral body”; and the third, the soul. Usually, we are locked within the elemental body and world with which our “individual” spirit is associated. But once this spirit is quieted or no longer active, “astral” phenomena and cognition become possible.

On the basis of his threefold division, Paracelsus, as Steiner describes it, then goes on to articulate a more detailed sevenfold division. There is first the elemental, or purely physical-corporeal body; within which there are the organic life processes that Paracelsus calls the “archaeus” or the “spirit of life.” The archaeus makes possible the “astral” spirit, from which the animal spirit emerges. This in turn makes possible the awakening of the “rational soul” within which, through meditation and reflection, the

“spiritual soul” able to cognize spirit as spirit, can awaken. Through immersion in the spiritual soul, a human being can experience “the deepest stratum of universal existence,” and ceases to experience itself as separate. We may call the final level the “universal spirit,” which knows itself in us. As Paracelsus says: “This ... is something great: there is nothing in Heaven and on Earth that is not in a human being. God, who is in Heaven, is in a human being.”

Turning to Paracelsus’s alchemical understanding of evolution, Steiner shows that his vision is monistic and developmental. The universe is in a state of becoming in, with, and through humanity, just as humanity becomes in, with, and through the universe—a relationship that unfolds and is perfected through human creativity, which is called to complete what nature begins. “For nature brings forth nothing into the light of day which is complete as it stands; rather, humanity must complete it.” Completing by art and science what nature begins is what Paracelsus calls alchemy, which is the “third column of medicine” (the first two are philosophy and astronomy; the fourth is virtue.): “This method of perfection is called alchemy. Thus the alchemist is a baker, when he bakes bread; a vintner, when he makes wine; a weaver, when he makes doth ...

[Therefore] the third pillar of medicine is alchemy, for the preparation of remedies cannot take place without it because nature cannot be put to use without art.” Yet nature is always primary. Paracelsus learns endlessly from nature and from his own experience. Certainly he takes his understanding of the four elements (fire, air, water, and earth) and the principles of sulphur and mercury from traditional alchemical cosmology. But from his experience, he creates the new triad of sulphur, mercury, and salt—combustibility, vaporability (solubility), and fixability, the residue—so that each object and each condition thus has its own sulphur, mercury, and salt.

In this short account, Steiner merely introduces Paracelsus as an important precursor of the anthroposophical

fall issue 2011 • 17

The universe is in a state of becoming in, with, and through humanity, just as humanity becomes in, with, and through the universe—a relationship that unfolds and is perfected through human creativity, which is called to complete what nature begins.

(Theosophical) approach to nature, but he does not mention the two central ideals that inspired Paracelsus’s life and work: the primacy of healing as the service to which we are called and the cosmic and earthly-human importance of Christ for this work. The time was perhaps not yet appropriate to do so. Yet these same two ideals, clearly and with a like primacy, inspired and motivated Steiner, too. For Paracelsus as for Steiner, every human being— thus every sickness, each patient—is individual and must be treated accordingly. For both, each individual arises out of and exists within a context: earthly-geographic, social, cosmic, and spiritual-karmic. (Not for nothing is Paracelsus known as the “father of environmental medicine.”) For both, the triadic nexus of sulphur, mercury, and salt processes is ubiquitous. Both, too, were homeopathic, not allopathic, in orientation and understood the primacy of the law of similars. Both made considerable use of minerals, in preference to herbs, in creating remedies. Both understood the “spirituality” of disease. And for both, Christ was present in all things.

Thus as the years of Steiner’s teaching unfolded we can observe these two ideals coming into ever greater focus. The centrality of Christ is self-evident; the devotion to healing perhaps less so. Yet reading between the lines it is equally dear. Throughout the next years, lectures on various aspects of health and illness, as wells as references to Paracelsus, Boehme, Basil Valentine, van Helmont, and those he calls “the old philosophers” (the alchemists) recur with regularity. At the same time, the depth of his research into the complex field of the spiritual, psychic, and physical-sensory interactions and relations that constitute the living human being increased from the lectures in the course Occult Physiology (1911) to the final hammering out of the understanding of the threefold human organism (1917). But these are only traces of a deeper, more passionate interest.

Confirming this interest, Rudolf Steiner sought contact with practicing physicians from the beginning, and there were always doctors among his students. Mention must first be made, of course, of Ita Wegman, later his dose collaborator and in a real sense the co-creator of anthroposophical medicine. She first met Steiner in 1902, and in 1905 on his recommendation moved to Zurich to study medicine. Ludwig Noll and Felix Peipers, for whom in 1911 Steiner created the sequence of heal-

ing images of the Madonna, date from the same period. Later, other doctors would join the Anthroposophical Society and begin to work medically out of what they were learning. Here two facts must be borne in mind. First, that for Rudolf Steiner anthroposophy was always simultaneously a path of spiritual research and a way of social and cultural ethical action. Research, although perhaps undertaken in a certain sense for its own sake, was never to be purely “theoretical.” That was anathema. Steiner did not believe in research that did not bear concrete fruit in life. Therefore, he is always exhorting his students to live the path of anthroposophy: to bring it into life, to manifest it for the sake of the greater whole. Second, that however cosmic and removed from human concerns anthroposophy sometimes seems, Steiner’s focus is always human beings in their concrete and in their specific individualities. While understanding human beings contextually as divine-cosmic-spiritual beings, his larger purpose is thus always to aid and further human-earthly evolution. He calls on human beings to know themselves not as “cosmic hermits,” but as “cosmic citizens”—citizens of the cosmos—who at the same time embody this knowledge in their arts, sciences, and social life. Thus Steiner’s research—even when focused on what appear to be the most arcane details of spiritual evolution—is always centered on the concrete human being. It follows from this that, as he was always pursuing a particular interest in healing, no matter what topic of research he was addressing, his findings would inevitably contribute toward the understanding of human health and illness.

All this came together in this first medical course— Introducing Anthroposophical Medicine. It was of course only a beginning. As Rudolf Steiner said in concluding:

It was difficult to begin .... But now that we are at the end, I must say that it is even more difficult to stop! ...I am speaking out of truly objective, not subjective, heartfelt feelings when I say to you, whose attendance here has demonstrated your great interest in this beginning, “Until we meet again, on a similar occasion!”

Many more lectures and lecture courses followed. The movement grew. Clinics were established. Together with Ita Wegman, he co-wrote in the last year of his life (1925) Extending Practical Medicine: Fundamental Principles Based on the Science of the Spirit. Fittingly, it was his last book. Anthroposophical medicine was launched.

18 • being human

Not for nothing is Paracelsus known as the father of environmental medicine.

Anthroposophy & Contemporary Philosophy in Dialogue

Observations on the Spiritualization of Thinking

by Yeshayahu Ben-Aharon1

What a great pleasure it is that I am able to be here with you. This is the first working visit that I have made to France. Strangely enough, though I don’t speak or read French, I have always closely followed the development of French cultural-spiritual life in the twentieth century and today and have been engaged particularly for many years with French thinking and philosophy. And I would like in this lecture to make you aware of the role French thinking plays in the invisible spiritual drama of our time.

I referred to what took place in the 20th century behind the curtains of world events in my books, The Spiritual Event of the 20th Century and The New Experience of the Supersensible, both written at the beginning of the 1990s. There I described my spiritual-scientific research on the esoteric, super- and sub-sensible realities graspable only by means of modern spiritual scientific research methods. Until the 1960s very little light was created on the earth at all—and so much darkness. Not that the darkness-producing forces and events have diminished since then; on the contrary, they increase exponentially. But the good news is that in all walks of life, thought, science, art, and social life, new forces of hope started to flow in the 1960s, and in my books I described the hidden sources out of which these spiritual forces are flowing. And some of those rare and precious rays of light emanated from French creativity in the second half of the last century.

During the whole European catastrophe of the 20th century, before, between, and after the two world wars and during the cold war, there took place in France a very intense and vital debate, intellectual but also cultural and political. The forces at work in thinking, with all their ingenuity, were not yet strong enough to penetrate social and political realities; many believed them to be so “revolutionary” and radical, but they could never really break through to new social ideas and social formations. But in the field of philosophy it was different; here some true creativity took place which was indeed striving to break new ground.

The last century had an enormous task coupled with the most grave and fateful results for good or ill. This task can be described in various ways. For our

1

fall issue 2011 • 19

This lecture was given to members of the Anthroposophical Society in Alsace-Lorraine, in Colmar, Alsace, France, on June 1, 2007. The occasion was initiated by the late Christine Ballivet, and its publication is dedicated to her.

purposes tonight, because we are approaching this task from the point of view of the development of thinking, we can call it the spiritualization of consciousness, or more specifically, spiritualization of the intellect and thinking. This is an expression often used by Rudolf Steiner. His whole impulse, the utmost exertion of his will and love, was poured into this deed. And his life long hope was that free humans would do what he himself was striving to do: truly to transform themselves! He had hoped that this would be achieved at least by a limited number of people already at the beginning of the 20th century, and that it would then be taken up by ever more people during the course of the whole century, reaching a certain intensive culmination at the end of the century. In a transformed manner it would then powerfully enter the global scene of the 21st century as world-changing creative power.

New Beginners

It is not enough nowadays that one person does something alone even if he is the greatest initiate, because others should no longer be simply led or pushed in his steps—unless we are speaking of impulses of evil. The good can only spring forth from the depth of free human hearts and minds, working together in mutual help and understanding.

And if you look at the world situation today, anthroposophy included, from this point of view, you can surely say: well, then, we are definitely only at the very beginning! We are all therefore kindly invited to begin again, anew. If we understand truly what was said above, we are asked to see ourselves as real beginners. Ever more people should understand that the Zeitgeist is now seeking new beginners, and is quite fed up with so many “knowers” who are constantly creating havoc in our social, spiritual and economic life.

This spiritualization of the intellect is the first and unavoidable step needed as foundation for further transformations of human nature and society. It is the precondition for the spiritualization of our social, cultural, political and economic life. This is our main entry point, simply because we have become thinking beings in recent centuries. Everything we do starts from thinking, and wrong thinking is immediately a source of moral-social destructive forces, while truthful thinking is a building and healing power.

For this reason Steiner referred to his so-called “nonanthroposophical” book The Philosophy of Freedom as his most important spiritual creation. By means of this book,

he said, if properly understood and practiced, each person can begin, without any former spiritual knowledge or belief, from her or his daily thinking consciousness, daily perceiving consciousness, daily moral activity and social experiences. Each can start here from where one stands in real life.

And I have had the experience, early on with myself and now also with friends and students in the world, that with The Philosophy of Freedom , if you take it in the right manner, it is indeed the case that it gives us powerful means to realize this spiritualization and bring it to consciousness. This was my own spiritual-scientific way of development from my 21st to my 35th year. After starting from Steiner’s general anthroposophical work, I then concentrated specifically on his philosophical-social work. For the building of the Harduf community, on the one hand, and for my spiritual research, on the other, I searched for the hidden stream of becoming of anthroposophy, for its living supersensible continuation.

How can Steiner’s starting point for thinking be continually updated, brought into the stream of the developing Zeitgeist ? This was my burning daily problem. I was also aware of the retarding forces at work inside his legacy. So I was conscious early on that I must create my own way as I go, alone, and that it is not simply given out there. And when you search in this way you have to find Michael’s footsteps in history and in present day spiritual, cultural and social life. This is the reason why I was intensively following the new developments in the sciences, arts, and social life, and also in thinking and philosophy in the course of the whole 20th century.

Then I found, through life itself, through my work itself—and this applies for my own experience, one cannot generalize—that whenever and wherever I looked for a way to continue after 1925, after Steiner’s death, the way to a further development of thinking and the spiritualization of the intellect was leading to the abyss opened with the last two German thinkers—the converted Jew Edmund Husserl and his National Socialist pupil Martin Heidegger—through the ruins of European culture in the Second World War, and into the 1950s and 1960s.2 And it was in this following in the tragic steps of Husserl and Heidegger that I came to French philosophy, because the French thinkers were the most ardent and receptive pu-

2 I wrote about my knowledge struggles in this regard in the introduction to the German translation of my book, The New Experience of the Supersensible. I describe the development of my spiritual researches in an interview added to the new English edition (2008).

20 • being human

pils of German thought. Therefore, in order to introduce some central figures of French philosophy I will have to briefly summarize the decisive turning point in German spiritual history.

A German Excursion

The first German thinker who was acutely aware that the time of German idealism and Goethe’s time had gone forever and cannot be revived was of course the great and tragic Nietzsche. He literally lost his mind in his efforts to find new, unforeseen venues to spiritualize thinking. And as historical symptom and clue to the gathering storm leading to the German tragedy it is significant that precisely in those years, the end of the 1880s, Steiner was working on his philosophical dissertation Truth and Science as basis for The Philosophy of Freedom . When the latter was published in 1894 he wrote to his close friend Rosa Mayreder how greatly he regretted the fact that Nietzsche could no longer read it, because “he would have truly understood it as a personal experience.” Now, Edmund Husserl (1859-1938) was a contemporary of Steiner; he also studied philosophy in Vienna under Franz Brentano one or two years after Steiner studied there, probably in the winter semester 1881-82. They almost met in Brentano’s classes, as it were. Karma couldn’t have spoken more clearly, because Husserl was striving to develop Brentano’s thinking further and created his phenomenology in the direction of Steiner’s Philosophy of Freedom. But Husserl’s radicalism was not radical enough; he didn’t overcome the deeper limitations of traditional, Kantian philosophy. This left in German thinking a yawning gap, an abyss, before, during, and after the First World War, which was the most decisive time for European and German history.

And the year came in which German destiny, and Europe’s, was to be decided: 1917. In this year Lenin is sent by Ludendorff in a sealed train carriage from his exile in Zürich to organize the Bolshevik revolution in the East; and the US enters the war from the West. Middle Europe’s fate was in the scales, tipping rapidly to the worst, and Steiner initiates social threefolding as a last rescue effort. Also in 1917 Brentano dies; Steiner publish-

es a “Nachruf”3 to Brentano in his book Von Seelenrätseln [Riddles of the Soul ]. Here philosophy, anthropology, and anthroposophy are brought together for the first time in a fully modern and scientific way, without any theosophical residues—free, that is, from traditional occult conceptions and formulations. This book states clearly that Steiner is now ready to start his real life task as a modern spiritual scientist and social innovator. But his hopes to create a world wide social-spiritual movement collapsed already before his early death in March 1925.