anthroposophy.org personal and cultural renewal in the 21st century a quarterly publication of the Anthroposophical Society in America summer-fall issue 2016 Integral Teacher Education (p.20) The Lear Elegies (p.24) What’s Wrong with Shakespeare (?) (p.34) The Currency of Self (p.37) The Brain is a Boundary (p.40) A Path to 2023 (p.48)

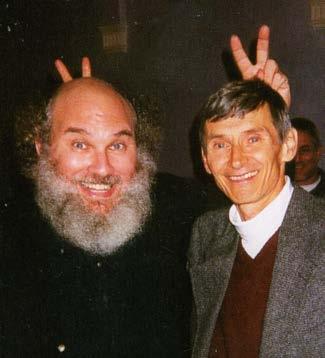

Tadadaho, the Peacemaker, and Hiawatha (l-r) Free Columbia Puppetry Project

being human

photo: Fumie Ishi

Volunteers are the lifeblood of Camphill Village. Every year, the Village welcomes dozens of volunteers age 19 and over from around the world to stay for a year–often longer–and become a member of our rich and vibrant community life. They live in a home with other volunteers, help manage their households, work alongside volunteers and adults with special needs in one of our many creative workplaces, and help care for their emotional, physical, and spiritual needs.

Volunteering Lifesharing Education

Join our integrated community for a year, a decade, or a lifetime of service, and learn how people with developmental differences are living a life of dignity, equality, and a sense of purpose

v House Leaders

v Workspace Leaders

v Service Volunteers

v Students of Social Therapy in the Camphill Academy

CamphillVillage.org

Volunteer@CamphillVillage.org

2 • being human Do you want to know why this year will be Significant? The new study year starts October 2016. Limited spaces available so reserve yours TODAY! www.studium.goetheanum.org Goetheanum Anthroposophical Studies in English

Representing Anthroposophy Transforming the World

Note the constant swing

Between self and world

And you will find revealed: The human-cosmic-being; The cosmic-human-being.

–Rudolf Steiner

Fall Conference and Annual Members’ Meeting of the Anthroposophical Society in America

October 7 - 9, 2016

with Virginia Sease, Joan Sleigh, Torin Finser, John Bloom, Fred Dennehy, Herbert Hagens, speech artists, eurythmists

Pre-conference gathering for members of the School for Spiritual Science, Thursday, October 6, 7–9pm (blue cards required)

Threefold Educational Center, Chestnut Ridge, NY

full details online at www.anthroposophy.org/agm2016

Programs and resources in visual arts eurythmy

music drama & poetry

Waldorf education spirituality

esoteric research economics

evolution of consciousness

health & therapies Biodynamic farming social action

self-development

WORKSHOPS

TALKS

STUDY

GROUPS

CLASSES

FESTIVALS EVENTS

EXHIBITS

UPCOMING EVENTS & PROGRAMS

ASTROSOPHY, THE NEW STAR WISDOM with Jonathan Hilton, Friday, October 14th, 7pm

ANTHROPOSOPHIC MEDICINE FOR EVERYONE, Wednesday, monthly David T. Anderson, starting Sept 14, Oct 12, 7pm

EURYTHMY, Monday, Monthly with Linda Larson, Sept 12, Oct 17, 7pm

ART EXHIBIT OPENING: KHALID KODI

October, date t.b.a.

MEMBERS’ EVENINGS, Friday, monthly for all members of the NY Branch or Anthroposophical Society; Sept 9, Oct 7, November 4

And in planning for Fall 2016: Kuehlewind memorial lecture; a new poetry series; a biography workshop; a talk on ‘making money matter’

Plus weekly & monthly study groups...

Rudolf Steiner Bookstore

Open Mon-Thurs 1-5pm, Fri-Sat 11am-8pm, Sun 11am-5pm; call for info: 212-242-8945

Steiner has “the most impressive holistic legacy of the 20th century...”

— NY Open Center co-founder Ralph White

Did you know?

Making a planned gift doesn’t usually affect a person’s current income.

For more information, contact Deb Abrahams-Dematte at deb@anthroposophy.org

BRING EXPRESSION TO YOUR INTENTION AND LOVE FOR ANTHROPOSOPHY INTO THE FUTURE

The New York Branch

Society in America

Anthroposophical

138 West 15th Street New York, NY – (212) 242-8945

asnyc .org centerpoint gallery

4 • being human

www.

spiritual therapeutic world & outsider artists ANTHROPOSOPHY NYC

Leaving a Legacy of Will

PlannedGiving_QTR AD_FINAL.indd 1 10/25/14 6:44 AM

Inspiring Waldorf Teacher Education

Since 1967

ALKION CENTER

specializing in Waldorf Teaching or Early Childhood Education

2-year, part-time diploma programs includes comprehensive Foundation Studies in Anthroposophy [can be attended separately]

One Week Summer Intensives in June & July

Alkion programs are recognized by AWSNA + WECAN

Low-Residency

Elementary & Early Childhood Teacher Education Programs with MEd Option

•

Professional Development and Introductory Courses & Workshops

ALKION CENTER | alkioncenter.org 330 County Rte. 21C, Ghent, NY

12075

CONFERENCE!

summer-fall issue 2016 • 5

• TEACHERS

NOVEMBER 4-5, 2016 www.sunbridge.edu

A New and Complete Translation in The Collected Works of Rudolf Steiner

Art History as a Reflection of Inner Spiritual Impulses

I am going to show you a series of reproductions, of slides, from a period in art history to which the human mind will probably always return to contemplate and consider; for, if we consider history as a reflection of inner spiritual impulses, it is precisely in this evolutionary moment that we see certain human circumstances, ones that are among the deepest and most decisive for the outer course of human history, expressed through a relationship to art.

Rudolf Steiner

This informal sequence of thirteen lectures was given by Rudolf Steiner during the darkest hours of World War I. It was a moment when the negative consequences of what he called “the age of the consciousness soul,” which had begun around 1417, were most terribly made apparent. In these lectures he sought to provide an antidote to pessimism. After describing the movement of consciousness from Greece into Rome, which coupled with influences from the Orthodox East, he showed how these influences transformed as the Middle Ages became the Renaissance. Replete with interesting information and over 800 color and black and white images, these lectures are rich and dense with ideas, enabling one to understand both the art of the Renaissance and the transformation of consciousness that it announced. These lectures demonstrate (to paraphrase Shelley) that artists truly are “the unacknowledged legislators of the age.”

ISBN 978-0-88010-627-6

432 pages | paperback | Full color illustrations | $45

SteinerBooks

order phone 703-661-1594

www.steinerbooks.org

Find Christ in a New Way

The Christian Community is a worldwide movement for religious renewal that seeks to open the path to the living, healing presence of Christ in the age of the free individual.

All who come will find a community striving to cultivate an environment of free inquiry in harmony with deep devotion.

Learn more at www.thechristiancommunity.org

6 • being human

Marcus Knausenberger

8 from the editors

11 being human digest

14 initiative!

14 Los Angeles Awake & Alive, by John Beck

16 Opening the Realm of New Mystery Dramas and Performing Arts, by Marke Levene

17 Celebrating Initiative: Threefold at 90, by Bill Day

18 Eurythmy Spring Valley Celebrates Forty Years, by Maria Ver Eecke

20 Integral Teacher Education, by Robert McDermott

21 Towards an Integrated Approach to Teaching, by Elizabeth Beavan

24 arts & ideas

24 The Lear Elegies, by Elaine Maria Upton

26 Shakespeare and the Esoteric, by Frederick J. Dennehy

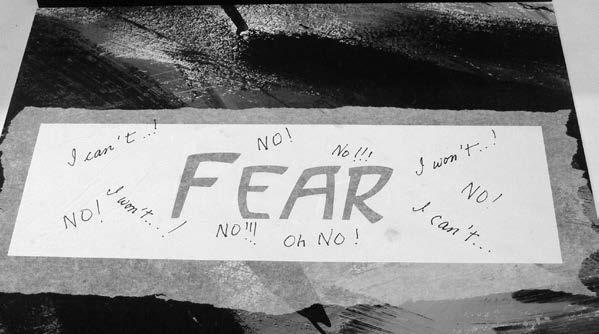

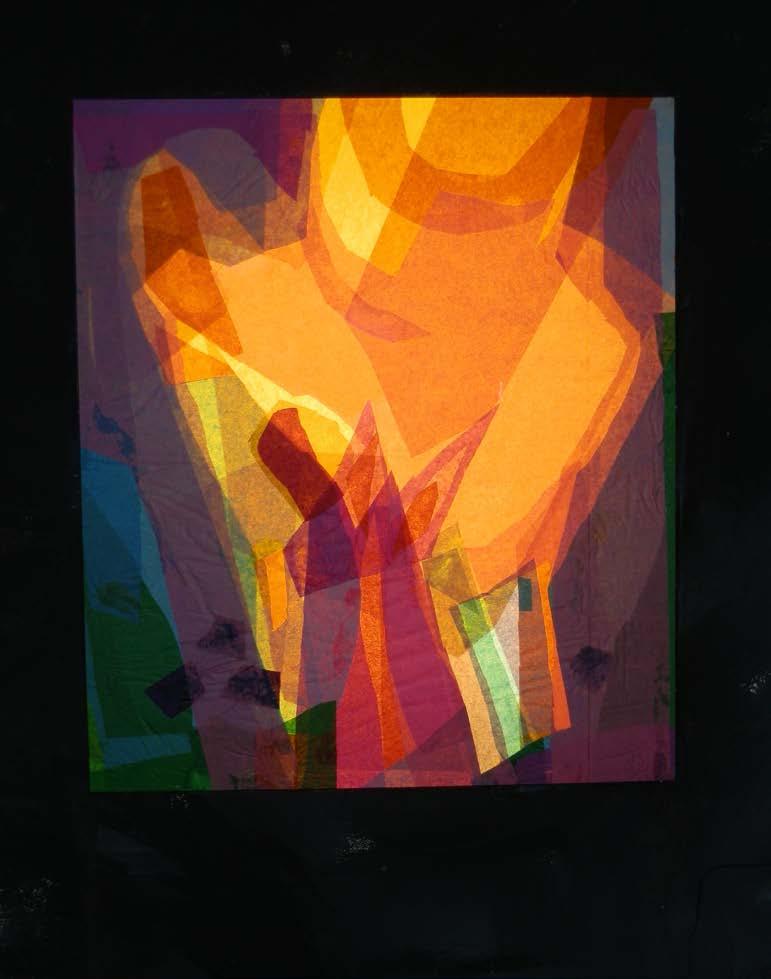

27 Gallery: Metamorphosis of Fear: An Exploration, by Elizabeth Lombardi

34 What's Wrong with Shakespeare (?), by Bruce Donehower

37 The Currency of Self, by John Bloom

39 Poems by Maureen Tolman Flannery

40 research & reviews

40 The Brain Is a Boundary, by Alexander Dreier; review by Frederick J. Dennehy

42 The Riddle of Consciousness: review of Eben Alexander's Proof of Heaven and The Map of Heaven, by Serguei Krissiouk 46

Vision of the Rudolf Steiner Library, by Douglas Sloan

for

members & friends

48 A Path to 2023, introduced by Torin Finser

“Steady As We Go,” by Katherine Thivierge

52 Many Shades of Green, Many Shades of Us, by Deb Abrahams-Dematte 53 News from the Rudolf Steiner Library, Hudson, NY, by Judith Kiely

by Laura Scappaticci 54

56 Ursel Pietzner, née Sachs, by Cornelius Pietzner

58 Ruth E. M. Finser: A Life of Transformation, by Siegfried Finser

60 Nancy Dow Anniston, by Michael Ronall

61 Dr. Mark Joshua Eisen, by Kathleen Wright

summer-fall issue 2016 • 7 Contents

Known!

news

The

47 Make It

by Sara Ciborski 48

49 Thank You, Marian León! 50 Welcome, John Bloom! 51

54

Greetings

the

New

Who Have Died

Welcome the New AnthroPops, commentary

to

Girasol Group 55

Members — Members

The Anthroposophical Society in America

General Council Members

Torin Finser, General Secretary

Carla Beebe Comey, Chair (at large)

John Michael, Treasurer (at large)

Dwight Ebaugh, Secretary (at large)

Micky Leach (Western Region)

Dave Alsop (at large)

Marianne Fieber-Dhara (Central Region)

Leadership Team

Deb Abrahams-Dematte, Director of Development

Katherine Thivierge, Director of Operations

Elizabeth Roosevelt, Interim Director of Programs

being human is published by the Anthroposophical Society in America

1923 Geddes Avenue

Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1797

Tel. 734.662.9355

www.anthroposophy.org

Editor: John H. Beck

Associate Editors:

Fred Dennehy, Elaine Upton

Design and layout: John Beck

Please send submissions, questions, and comments to: editor@anthroposophy.org or to the postal address above, for our next issue by 12/15/2016.

©2016 The Anthroposophical Society in America. Responsibility for the content of articles is the authors’.

from the editor

Dear Friends,

This is the first issue of being human which will not have been reviewed in galley proofs by Marian León. It was one of many ways she supported my work as editor and communications director from January 2009 to this year. After carrying a huge workload with exceptional grace, Marian has taken a post with the University of Michigan (see page 49). I find that it is qualities of co-workers that make it possible to perform endless triage as needed in any non-profit, between great mission and scant resources. Thank you, Marian!

I want to thank Katherine Czapp, whose health prevented her from continuing her fine proofreading, and Cynthia Chelius of the ASA staff for taking on this work which, at its best, is never noticed! And this is also our last issue with First Impression Printing; Terry and Steve Weaver retire at the end of August. We’re all grateful for their enormous patience and good work.

Learning from difficult times and emotions is a theme this issue. Our cover shows the Iroquois Peacemaker Deganawida, a great spiritual ancestor for all North Americans. Page 24 begins a section focused on Shakespeare and his unsurpassed revelation of the struggles of good and evil in human souls. The Gallery in this issue (page 27) presents Elizabeth Lombardi’s “Metamorphosis of Fear: An Exploration.” Do take time with the five images and then review the sequence of thoughts for each one. Our final life story, that of Dr. Mark Eisen (page 61), told with loving care by Kathleen Wright, was an actual battle with demons. (All four obituaries, pages 56-63, express so well why we choose to call this publication being human.)

The Fall Conference, described on the previous page, will carry the global theme anthroposophists are working with this year: “world transformation and self-knowledge in the face of evil.” I do hope to see many of you there!

At the conference we have a new General Secretary. Torin Finser has been a very great help and understanding friend of being human. He introduces “A Path to 2023” (page 48), an exciting and challenging opportunity to move into the future. Like Torin, incoming General Secretary John Bloom is a fine writer. On page 37 we have his essay, “The Currency of Self,” and on page 50 is the letter about the selection process.

And this is a poetry issue: Elaine Upton’s, on Lear ; Alexander Dreier’s, quoted in Fred’s review (p. 40); Maureen Flannery’s, on pages 23 and 39!

A final correction: Joan Treadaway sent us the article, “Nurturing the Beings of the Schools” (Easter-Spring issue 2016, page 19), but it was written by her fellow Arizonan (from Tempe) Peter Rennick. Thank you, Peter!

John Beck

HOW TO receive being human, or to comment or contribute

Copies of being human are free to members of the Anthroposophical Society in America (visit anthroposophy.org/join or call 734.662.9355). Sample copies are also sent to friends who contact us at the address below. To contribute articles or art please email editor@anthroposophy.org or write Editor, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48104.

8 • being human

This issue marks the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death in 1616 with three pieces celebrating him. Elaine Upton, who serves as editor for the book review section, has submitted a series of poems entitled “The Lear Elegies,” patterned loosely after Rilke’s “Duino Elegies.” They embody her exploration of Imagination and Nothingness, presented around Shakespeare’s drama of King Lear. It is a pleasure to give our readers these intimate responses to Shakespeare’s most intimate tragedy.

It is also a pleasure to include “What’s Wrong With Shakespeare?” by Bruce Donehower. Bruce has isolated the One Thing Wrong With Shakespeare in order to discover “What’s Right With Shakespeare.” I am not sure if I know of anyone who has articulated Shakespeare’s gift of negative capability better in modern terms: “… If we find ourselves outside the consolation of a meta-narrative that makes a tidy fable of human life, then we walk in freedom with the Bard.”

There is also an essay of my own, considering esoteric meaning in Shakespeare.

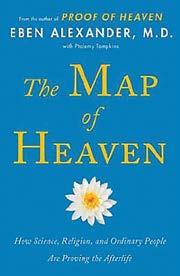

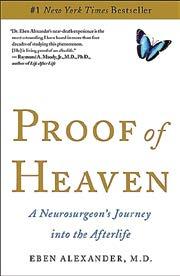

We have a review by Serguei Krissiouk, a medical professional, of two books that have received great attention recently in the popular press—Proof of Heaven: A Neurosurgeon’s Journey Into the Afterlife and The Map of Heaven: How Science, Religion and Ordinary People are Proving the Afterlife, both by Eben Alexander, M.D.

Dr. Krissiouk’s review follows previous reviews by Walter Alexander of Sam Parnia’s Erasing Death and Sara Ciborski’s review of Irreducible Mind: Toward a Psychology for the 21st Century by Edward F. Kelly and others.

The review finds common ground between Near Death Experiences and anthroposophy and, like the other reviews mentioned, calls for an open conversation between anthroposophists and modern explorers of the mysteries of consciousness and death.

Finally, I have reviewed The Brain is a Boundary: A Journey in Poems to the Borderlines of Lewy Body Dementia by Alexander Dreier, a collection of poems that explore a number of boundaries, including the one between perceptual distortion and poetic imagination. Readers will be gripped by the account of Mr. Dreier’s experience with the challenge of Lewy Body Dementia, but the heart of the book is not so much the etiology of his condition as the wonder of the rich array of his poetic gifts.

Frederick Dennehy

Frederick Dennehy

summer-fall issue 2016 • 9 JOIN ONLINE AT www.anthroposophy.org/membership Insight Inspiration Community

HUMANITY’S PATH AND YOUR OWN. BECOME A MEMBER TODAY!

Contact us at

734.662.9355, or visit www.anthroposophy.org

EXPLORE

Questions?

info@anthroposophy.org or

source development. the and wide Waldorf medicine, therapeutic insight

WE INVITE YOU TO

ANTHROPOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN AMERICA

Inspiration Community

EXPLORE HUMANITY’S PATH AND YOUR OWN.

BECOME A MEMBER TODAY!

WELCOME! We look forward to meeting you!

JOIN ONLINE AT www.anthroposophy.org/membership

Name Street Address City, State, ZIP

AND YOUR OWN. BECOME A MEMBER TODAY!

Odyssey Journeys 2017

Temples, Pyramids, Sekem community

EGYPT

March 25-April 9

Sail the Nile in a traditional dahibiya.

Benefits of membership

• Connecting with

• The print edition initiatives, arts, ideas,

• Membership in the community founded Switzerland

• Borrowing and research the Society’s national

• Discounts on the and store items

• After two years for Spiritual Science, Are there requirements Steiner’s work in the Questions? Contact

All inquiries by September please

GREECE

10

Telephone

Questions? Contact us at info@anthroposophy.org or 734.662.9355, or visit www.anthroposophy.org

Email

Occupation and/or Interests

Date of Birth

The Society relies on the support of members and friends to carry out its work. Membership is not dependent on one’s financial circumstances and contributions are based on a sliding scale. Please choose the level which is right for you. Suggested rates:

❑ $180 per year (or $15 per month) — average contribution

❑ $60 per year (or $5 per month) — covers basic costs

❑ $120 per year (or $10 per month)

❑ $240 per year (or $20 per month)

❑ My check is enclosed ❑ Please charge my: ❑ MC ❑ VISA

Card #

Exp month/year 3-digit code

Signature

Complete and return this form with payment to: Anthroposophical Society in America 1923 Geddes Ave, Ann Arbor, MI 48104 Or join and pay securely online at anthroposophy.org/membership

• being human

ANTHROPOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN AMERICA

With Van James Athens, Delphi, Patmos, Ephesus, and more.

June 26-July 28

For information contact Gillian at 610.469.0864 or gillianschoemaker@gmail.com

Insight Inspiration C

Insight

sale at WaldorfBooks.com – details at OrganicThinking.org

“A how-to book for writing from and to the heart...”

On

being human digest

The digest offers brief notes, news, and ideas from holistic and human-centered initiatives. E-mail editor@anthroposophy.org or write “Editor, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI, 48104.”

MEDICINE

Anthroposophic Medicine Getting Stronger

Dr. Adam Blanning has sent us a lengthy report too late for this issue. It is intriguing, however. He begins: “There have been some important events related to the growth of anthroposophic medicine, in the US and internationally, over the last several months. It is possible to feel the stirrings of new organizational and outreach possibilities—which is appropriate, as PAAM, the anthroposophic physicians’ association is 35 years old!

“An important prelude came in October 2014, with the founding of the Academy of Integrative Health and Medicine (AIHM), a new umbrella organization which replaced the previous American Holistic Medical Association and Board of Holistic Medicine in the United States. One of the board members of AIHM, David Riley, arranged for PAAM (the Physicians’ Association for Anthroposophic Medicine) to be invited as one of the member associations. Since that time, PAAM has joined as a member association of AIHM and made steps toward collaborative activity, participating in association working groups and prioritizing PAAM board members’ attendance at the annual AIHM conference.”

If you would like a PDF copy of the full report by email, write to editor@anthroposophy.org and ask for “Dr. Blanning’s report.”

Resonare

Foundation Course in Music out of Anthroposophy

Our Mission:

● to encounter tone and interval in their

● spiritual as well as physical aspects

● to explore the phenomena of music

● through experiential research and study

● to foster creativity in a collaborative setting

● to re-awaken inner listening

AGRICULTURE Farming the Living Earth

We’re fans of the Biodynamic Association’s blog at biodynamicsbda.wordpress.com. Like a good social creature, it gathers from many fine sources. An August post, from Light Root Community Farm’s Summer Newsletter (Boulder, CO), begins, “We are in the midst of the hazy summer dream time here on the farm—long hot days abuzz with activity. The days seem to run into one another, waking early and working late into the evenings on the farm. Our summertime schedule is a solid rhythm of early morning milking and farm chores, mid-day lunch break and siesta time to escape the heat of the day, and when the heat breaks we emerge back out for an evening session... as the sun sets behind the foothills.” A strong

www.bacwtt.org

summer-fall issue 2016 • 11

Create Space for a Natural Childhood Study with us to become a Waldorf Teacher

479 4400

tiffany@bacwtt.org 415

Begins September 2016 RESONARE.ORG

Studies in phenomenology, music theory, lyre work, singing, evolution of consciousness through music, Spacial Dynamics®, eurythmy, & improvisation. Five long weekends in 9 months.

being human digest

contrast to heat-evasion of city and suburb!

Another post addresses the Association’s biennial conference, November 16-20 this year in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The theme is Tierra Viva: Farming the Living Earth. Co-director Thea Maria Carlson writes, “The understanding that the earth is alive was once widespread— and still exists in many indigenous cultures and spiritual traditions today. Yet for centuries the dominant Western culture has treated the earth as an inanimate object, a storehouse of resources for us to extract, and a sewer to absorb our wastes. Industrial agriculture arises from and perpetuates this mindset, reducing the soil to a dead substrate whose only value is in the number of pounds of grain that can be harvested from it each year.” Read more at www.biodynamics.com/2016conference

Art Section Online

Another valuable resource is the North American Art Section website [northamericanartsection.blogspot.com]. Along with galleries, links, and blog posts, it offers free examination of the latest Art Section Newsletter, beautifully produced by David Adams, and subscriptions are available. The contents of the spring-summer issue now online include:

• Circle and Cross: Icons of Life and Death, by Van James

• Report on Svi Szir’s Workshop at Free Columbia

• Winged Beings, by Gertraud Goodwin

• The Human Heart: An Artistic Exploration, by J. Chequers

• Dancing with Colors, by Doris Harpers & Nikola Savic

• A Dialogue on Issues of Anthroposophical Art, Pt. 2

• An excerpt from “Through the Gate of Sense Impressions to the Etheric”

• Stop Press! New Book: Metamorphosis

The newsletter is typically forty pages and profusely illustrated, with the PDF in full color. Take a look.

HUMANITIES

Deepening Meditation

The Logos Working Group is a meditation group that meets every fall to carry on the work of Georg Kuhlewind (1924-2006). In its early years with Kuhlewind, the group was known as the Therapists’ Working Group because many participants were from the healing professions. However, meetings have always been open to anyone wishing to deepen a practice of meditation.

New Books for Educators and Parents

Edited by Ruth Ker $14

Edited by Ruth Ker $14

Kuhlewind was the foremost exponent of anthroposophy in Hungary, and a prolific author (The Life of the Soul, From Normal to Healthy, The Logos Structure of the World, The Light of the “I,” and The Gentle Will: Meditative Guidelines for Creative Consciousness). Until his death, he visited the US twice yearly to hold retreats, give seminars and talks, and meet with groups, including teachers, doctors, therapists, and branches of the Society from California to New England. His research encompassed psychology, epistemology (he had a profound connection to the The Philosophy of Freedom), esoteric Christianity, New Testament studies, child development, linguistics, Zen Buddhism, and the philosophy of science.

12 • being human

From Kindergarten into the Grades: Insights from Rudolf Steiner

Creating Connections: Perspectives on Parent-andChild Work in Waldorf Early Childhood Education Edited

The Singing, Playing Kindergarten Daniel Udo

Haes,

E-mail: info@waldorfearlychildhood.org www.waldorfearlychildhood.org (845) 352-1690 Fax: (845) 352-1695 Please Visit Our Online Store! store.waldorfearlychildhood.org

by Susan Weber and Kimberly Lewis $14

de

translated by Barbara Mees $22

ART

being human digest

A gifted and inspiring teacher of meditation, Kuhlewind always offered only what he had achieved through his own inner work. He declined the role of leader, asking those who came to his workshops to take responsibility and initiative. The Logos Working Group continues in this spirit: a focus group suggests themes, any participant may guide sessions, and we encourage improvisation. Over the course of a three-day meeting, we work meditatively with texts, images, or themes; report, reflect, and listen; and share breaks, meals, and an evening of social activity.

The meetings are held Friday through Sunday, November 18-20, 2016, at the Farmhouse at Wisdom House, a retreat center in Litchfield, CT. It is an ideal site with comfortable rooms, delicious food, lovely grounds, and reasonable rates. Anyone interested in learning more may contact Joyce Reilly at 201-213-6294 or joycereilly@aol.com

EDUCATION

Resonare Means Music

Resonare is an anthroposophic music foundation course for musicians, music educators, class teachers, eurythmists, and fellow seekers on the path of spiritual knowledge. Its mission is to offer students an opportunity:

1. to encounter tone and interval in their spiritual as well as physical aspects

2. to explore the phenomena of music through experiential research and study

3. to foster creativity in a collaborative setting

4. to re-awaken inner listening.

New Times… New Model

It meets five weekends over the course of nine months. The rhythm for each weekend consists of an evening dinner and sharing on Thursday, classes all day Friday and Saturday, and an artistic review on Sunday morning. The curriculum covered in each weekend session includes phenomenology, music theory, lyre work, singing, studies in the evolution of consciousness through music, Spacial Dynamics®, eurythmy, and improvisation. An article by Catherine Decker explains:

Foundational to the Resonare program is a new conceptualization of the theory of music. Examining relationships among modes, scales, and keys within this framework, a future-bearing aspect of the musical experience is discovered.

The lyre serves an essential role in our listening work. By releasing the tone from the physicality of the instrument, the lyre informs us about the true nature of the tones themselves. As an instrument that reflects the essence of tonal character, the lyre supports our investigation of intervals and their relationships.

Part of each session is devoted to singing, based on the approach of Valborg Werbeck-Svardstrom. Students learn to uncover their voices, allowing a natural stream of vocalization to be revealed.

Improvisation enables participants to work with pitch, rhythm, and phrasing in new ways, leading to a fuller understanding of the interaction of musical elements. Various stringed and metal instruments all lend themselves to our improvising together. This activity strengthens our listening while asking that we stay in the present moment.

Resonare takes place in Philmont, NY. Online it is at www.resonare.org. First weekend is September 8-11th.

Spacial Dynamics® Core Studies Program

Mechanicville, New York

Portland, Oregon

October 6-10, 2016

November 6-10, 2016

summer-fall issue 2016 • 13

For the first time, one can receive a training in Spacial Dynamics with a 2 year part-time program led by Jaimen McMillan in New York or Oregon, and then subsequent courses of specialized interests by certified Level III trainers at locations around North America.

IN THIS SECTION:

Initiatives small and large dot the sprawling landscape of America’s second largest city.

Marke Levene and friends have successfully shared a new mystery drama in “Readers Theater” format; their plans for international performance go ahead.

Starting ninety years ago as a farm to provide food for New York City’s anthroposophical restaurant, Threefold is a rich and mature community.

Forty years ago the first eurythmists trained on North American soil received their diplomas.

San Francisco’s CIIS is exploring the possibility of a Waldorf-based integral teacher training with advanced degrees.

Elizabeth Beavan’s description of an “integrated approach to teaching” sounds like a step toward Rudolf Steiner’s dream of shifting the educational expectations of all schools.

Los Angeles Awake & Alive

by John Beck

by John Beck

Seizing a chance to spend two winter-spring months in Los Angeles, I was able to enjoy the second largest US metropolis, experience its quite adequate public transit, and touch base with some anthroposophical initiatives. Finally I saw the Rudolf Steiner Community Center, beautiful home of the Los Angeles Branch of the Anthroposophical Society in downtown Pasadena, for two house-filling lectures: Rev. Bastiaan Baan on “The Origins of Evil” and Dr. Peter Selg on “Rudolf Steiner and Christian Rosenkreutz.” A Shakespeare workshop with associate editor Fred Dennehy was coming, and the Center’s 25th anniversary was celebrated in June.

On my two visits I greeted retiring branch president Jane Hipolito and husband Terry (two stalwarts of the Literary Arts and Humanities Section), Linda Connell of the Western Regional Council and its former General Council representative, author-translator Philip Mees, Margaret Shipman of the GEMS national study group and Traveling Speakers Program, former General Secretary MariJo Rogers visiting from Sacramento, and educational consultant Joan Jaeckel, now working on the startup ShadeTree School in Watts. The Branch has a large meeting room and stage, plus a library and seminar space, and a bookstore and reading room. Branch and related activities—study groups, arts classes, therapies—are listed at www.anthroposophyla.org.

Pasadena is a town north and east of LA city in Los Angeles county. In Altadena, between Pasadena and imposing mountains to the north, I called on Truus Geraets, therapeutic eurythmist and social activist on three continents. Her site at www.healingartofliving.com says, “Truus’ life included many endeavors, as she discovered how she could best serve ‘the future.’”

Elderberries Threefold Café (four stars on Yelp, 253 reviews; elderberriescafe.org ) is right on Sunset Boulevard in the middle of

14 • being human initiative!

The LA Branch: at the door, reading room, meeting hall.

Hollywood. Dottie Zold and friends’ visionary vegan hangout “strives to nourish the human being as a whole. We see our work starting with providing healing, nourishing food and drink, and ending with the creation of a world where every individual is allowed a dignified life truly worthy of the human being! We feel that we must start right now, right here, creating the world we want to see!”

Elderberries’ story is actively unfolding, rhizome-like. First offshoot is Have Seeds Threefold House, “a five-bedroom wayfarers’ inn and co-learning hub in the heart of LA, where wanderers, seekers, and students of life find home.” You can become a patron at patreon.com. When I dropped by, Emerson activist Stuart Weeks was talking with householders and Elizabeth Roosevelt, now ASA Interim Director of Programs, on the front porch. The next offshoot? Atlanta, which may extend as a “grailway” back to Nancy Poer’s ranch in Northern California. This whole millennial story unfolds best on Facebook!

At Elderberries I spoke for a few minutes with Caleb Buchbinder, who spoke at the fall conference in St. Louis last year about “Classroom Alive” which had organized a walking/learning trip from Sweden to Greece. Another walk took place in Los Angeles in January (map below). The journey comes to life in a video at Vimeo [vimeo.com/156753068]. A sample day, early on:

“Day 3. This morning we develop our capacity for taking joy in scraping the spilled pot of oats from the ground into hungry morning mouths. The day begins and with the first steps we have left the womb of the canyon and hit the hard pavement. Laughter is close on our heels, and as we flop down for lunch a flurry of free tacos rain down upon us. Already it is striking how at home we can be, getting water in the fire station, singing for the strangers we pass, making a lunch table in an unassuming patch of green. All around us the imposing structures of wealth rise up; walking on roads with no sidewalks in the wealthiest zip-code in the world we wonder at the lives lived here. Arriving at our destination for the night we are welcomed with pure generosity into a small retreat center in Beverly Hills. We spend the night hearing stories of our hosts’ work in creating the Earth to Paris campaign for COP21.”

Finally there’s who I didn’t see this time. The City of Angels sprawls over 500+ square miles between ocean and mountains. By natural gift it would be a small city; it blossomed thanks to the gift of imported water. And as the Hollywood “dream factory,” it is center of a century-long and global inundation of popular culture. Matre Matt Sawaya [facebook.com/matre.mattsawaya] is here, rapping and making videos about demilitarizing the LA schools. Filmmaker Matthew Temple (“The Girls of Summer”) of the former WeStrive.org is here, and Orland Bishop and ShadeTree Multicultural Foundation [www.facebook.com/shadetreefoundation]. Schools, teacher training, therapies, artists, students. A large, deep, quiet ferment. One must come back.

John Beck is editor of being human

“Sergei Prokofieff lectured on the Christmas Conference at the 2002 year-end conference at the Goetheanum. He contrasted the new mysteries with the old mysteries. The mysteries were the places in ancient times where spiritual wisdom was taught to selected pupils. In these mysteries pupils were given responsibilities as they progressed along their path of development. Their teacher observed their progress and gave them tasks and responsibilities suitable to their level of development. Anthroposophy belongs to the new mysteries. They are mysteries of the will. They are based entirely on freedom. We see what needs to be done, what needs to be supported. Then we take on these responsibilities ourselves to the extent we are able. No one assigns us responsibilities. We take them up freely.”

— From Linda Connell’s essay on the mission page of the Los Angeles Branch of the Anthroposophical Society.

summer-fall issue 2016 • 15

Above, Have Seeds Threefold House; below, Elderberries crew at the counter

Opening the Realm of New Mystery Dramas and Performing Arts

by Marke Levene

Lemniscate Arts has taken a major step toward our goal of bringing a trio of performances—symphonic eurythmy, a Shakespeare play, and a new mystery drama— to places both familiar and unfamiliar with the majesty and scope of performance art inspired by Rudolf Steiner.

Those who have followed our progress can share our joy at having entered onto a new level of activity with our recent Readers Theater tour. In Copake, NY, Chicago, and Fair Oaks, CA, eighteen different artistic readers presented The Working of the Spirit, the new mystery drama showing next steps in the lives of the characters of Rudolf Steiner’s four dramas.

These readings were received with a great deal of enthusiasm. From the beginning of work on this text in Delphi, Greece in 2013, we have had an overarching question whether an audience unfamiliar with Steiner’s Mystery Dramas or anthroposophy would be able to find a pathway to comprehension of this imagination. Of those who participated as actors or audience in the Readers’ Theater, and had either no knowledge of Rudolf Steiner’s dramas or of anthroposophy, many expressed comprehension and a direct connection to their own soul questions.

We are now preparing Readers Theater presentations in England, in Gloucester and Forest Row, in October, and in New Zealand and Australia in November. These events will offer an edited version as part of our process of preparing to bring the full play onto the stage. Through Readers Theater presentations we also seek out acting and speech talent, musicianship, and other production skills.

SteinerBooks will offer the full text of the play in September with copies available in retail outlets and our web site, workingofthespirit.org . The site will also offer “Gift/Tickets” which have already proven successful in helping fund the tour preparation. The Gift/ Ticket impulse reflects the

growth of “crowd funding” where large numbers of people making modest contributions can unlock sufficient resources for endeavors that previously could only have been funded by wealthy individuals and foundation or government grants. The Gift/Ticket idea creates the possibility to build a project “of the people,” recognizing and participating in an artistic, global celebration.

A $100.00 contribution is the cost per Gift/Ticket, so a relatively modest contribution allows people to share in our developmental process in a living, dynamic way. The donor receives a voucher that can be exchanged anywhere in the world for a ticket to any performance. The risk associated with the Gift/Ticket is that if we do not manage to raise sufficient capital to bring this tour into being there will be no performance to redeem the voucher for.

We recently received confirmation that a European Trust will help support our performances in Europe. Combined with individual gifts and institutional grants, Gift/Ticket support has made our work to date possible. We hope it will be part of building the project as a community activity towards the meaningful goal of placing Steiner-inspired performance arts into a wider picture of contemporary culture. Symphonic Eurythmy, Shakespeare, and a new drama will bring images of the interplay between the physical and spiritual worlds onto the stage. Now, with sufficient capital we will move directly towards venue location and local community support globally.

With gratitude to the many people involved in our development and hundreds of supporters who have made it possible to get this far!

Marke Levene (marke@ workingofthespirit.com) is an actor, speech artist, eurythmist, and entrepreneur centrally involved in tours of Rudolf Steiner’s mystery dramas and of eurythmy performances with full orchestra. He served for many years on the Council of Anthroposophic Organizations.

16 • being human initiative!

The Readers Theater group in Chicago, in front of the Rudolf Steiner Branch.

Celebrating Initiative Threefold at 90

By Bill Day

By Bill Day

The year 2016 brings the ninetieth anniversary of the purchase of Threefold Farm in Spring Valley, NY, by Ralph Courtney, Charlotte Parker, and other members of New York City’s Threefold Group. As we started contemplating celebrations and observances, we quickly realized that a host of landmark events at Threefold took place in years that end with the number 6: the founding of Threefold Farm (1926), the opening of Ehrenfried Pfeiffer’s Biochemical Research Laboratory (1946), the opening of Green Meadow Waldorf School’s first building (1956), the founding of the Fellowship Community and the Camphill Foundation (both 1966), Green Meadow’s first twelfth grade graduation (1976), the Waldorf Institute’s relocation to Threefold as Sunbridge College, and the founding of the Eurythmy Spring Valley Performing Group (both 1986), and the founding of the Pfeiffer Center and the Fiber Craft Studio (both 1996).

All those anniversaries cried out for a party, so on Saturday, May 21, a couple hundred of our closest friends gathered on the Main House lawn for games, speeches, a delicious buffet dinner (featuring updated menu items from Threefold Restaurant menus of the 1920s), cupcakes, skits, and sparklers. The New York Branch sent flowers and a note wishing us “another century of work—together!” and Dorothea Mier offered the hope that “such an event can truly bind us all together, more united, to go into the future having looked at the past.”

This fall, we look forward to welcoming friends from across the country for the Anthroposophical Society’s Fall Conference and AGM, “Representing Anthroposophy” from Thursday, October 6th through 9th. Come Celebrate Initiative with us!

summer-fall issue 2016 • 17

Pictured from top left, counter-clockwise: Judith Brockway Aventuro reflected on nearly 40 years in the community; Rafael Manaças, Executive Director of Threefold Educational Foundation; Jeanette Rodriguez, director of the Otto Specht School; long-time Fellowship Community resident Michael Laney; Karl Fredrickson, Ann Scharff, Lady Carter, Ann Courtney Pratt; Carol Avery, Sayre (Sally) Burns, Mariel Farlow; Dorothea Mier, Beth Dunn-Fox, Patrick Kennedy; Michael Scharff, Maiken Nielsen, Julian Liu; Skip Herman with granddaughter Serena and the festive menu; everyone enjoying after-dinner skits...

Eurythmy Spring Valley Celebrates Forty Years!

by Maria Ver Eecke

by Maria Ver Eecke

As Threefold marked its 90th, the School of Eurythmy Spring Valley celebrated its 40th anniversary. Graduations at ESV are always grand events and friends come from afar, creating a mood of homecoming. After a two-hour performance in the Threefold Auditorium and a reception in the Threefold Café, at the stroke of midnight comes a skit where the teachers are roasted in good natured humor and the audience

realizes just how well these students know each other, as the graduates are portrayed by their classmates.

This special year honored the original alumni, the “A” Class of 1976 (pictured above, right). We gathered for tea in their first classroom, the home of Lisa Monges. Faculty and staff of Eurythmy Spring Valley and Threefold were the hosts. The alumni who attended were Kristin Hawkins, Alys Morgan, Grace Ann Peysson, and Carol Ann Williamson. Nancy McMahon and Francesca Margulies were unable to attend. Siegfried Finser stood in for his late wife Ruth. We were served scones with clotted cream, strawberries, and herb tea fresh from the garden.

After introductions, personal stories were told, giving space to our elders, who paved the way for all of us. I was moved by the way the younger eurythmists listened.

The School was the initiative of Kristin Hawkins, who asked Lisa Monges if she would begin a eurythmy training, as Lisa had the recognition from the Goetheanum Council to grant eurythmy diplomas. Lisa responded that such a training was best as a group process, and soon others joined the class. Kristin, a Waldorf alumna, had been doing eurythmy since she was ten years old.

Now, with a family of five, she was unable to attend the eurythmy trainings in Europe. For many years, Kristin taught, performed with stage groups, and gave therapeutic eurythmy lessons at the Fellowship Community, Green Meadow Waldorf School, and the Rudolf Steiner School in NYC.

Grace Ann Peysson remembered coming from Emerson College in 1965 to be the cook at the Threefold Farm. Many anthroposophical conferences took place during the summers. She spoke of the youth movement that met here in 1970. Grace Ann is presently living and working at Camphill Village Kimberton Hills, Pennsylvania.

Ruth Finser gave therapy sessions to children from the Hawthorne Valley and Great Barrington Rudolf Steiner schools, as well as having a private practice within her home. Nancy McMahon gave therapeutic eurythmy sessions at Raphael House and the Sacramento Waldorf School, as well as teaching a few groups of hygienic eurythmy at the Rudolf Steiner College. Francesca Mar-

18 • being human initiative!

Grace Ann Peysson, Siegfried Finser, Carol Ann Williamson, Kristin Hawkins, Alys Morgan.

Dorothea Mier, Annelies Davidson, Elsa Macauley.

L-R, back row: Kari van Oordt, Lucille Clem, Virginia Brett, Lisa Monges, Marianne Schneider, Norman Vogel, Maidlin Vogel, Margarete Proskauer-Unger (teachers); front row: Carol Ann Williamson, Grace Ann Peysson, Alys Morgan, Nancy McMahon, Francesca Margulies, Kristin Hawkins, Ruth Finser (Class “A”)

LECTURE–DEMONSTRATION PROJECTS FROM THE “A” CLASS

Language & Human Development & Its Renewal through Eurythmy — Ruth E. M. Finser

Consciousness in Movement — Francesca Margulies

How Anthroposophy Reveals Itself in Tone Eurythmy through the Classic & Romantic Periods — Alys Samuels-Morgan Space, Form, & Color in Eurythmy — Grace Ann Peysson

The Expression of the Inaudible in Tone Eurythmy — Nancy McMahon

The Romantic Impulse in Literature as Revealed through Shelley’s Work and the Expression of Thinking, Feeling, & Will through Eurythmy — Carol Ann Williamson

Approaches to Public Classes in Eurythmy — Kristin Hawkins

gulies performed and taught eurythmy at Pinehill, Monadnock, and Great Barrington Waldorf schools. Alys Morgan was a founder of the Mountain Laurel Waldorf School in New Paltz, NY, where she continues to teach eurythmy in kindergarten through eighth grade. Carol Ann Williamson is a therapeutic eurythmist, presently working at the Otto Specht School in the Threefold Community. (Six of the seven eurythmists of Class “A” became eurythmy therapists!) Siegfried Finser was recognized as the administrator who also developed a toymaking workshop for students in a work-study program.

Looking back, one felt that the weavings of destiny were at work: that the question was asked and the teachers and students came together to found the School of Eurythmy on this continent. At the beginning of the graduation performance that evening, Barbara Schneider-Serio invited the alumni onto the presidium to recognize them publicly. An honorary diploma was given to each one.

Congratulations to the alumni and the faculty of Eurythmy Spring Valley! May this good work continue to grow and flourish.

Maria Ver Eecke (editor@eana.org) is Editor of the Newsletters of the Eurythmy Association of North America (EANA) and the Association of Therapeutic Eurythmists in North America (ATHENA).

Eurythmy Spring Valley

On June 4th, 2016, the fourth-year class of the School of Eurythmy Spring Valley presented their graduation performance at the Threefold Auditorium for family, friends, and all who have supported them on an incredible journey. The three students in the “KK” Class are from Taiwan, Canada and the US. Their graduation program included works by J. S. Bach and Brahms, Rudolf Steiner, Kathleen Raine, Dag Hammarskjold, a Sicilian destiny story, and many humorous selections.

“When you land at one of the airports ... one of your first glimpses is of the tremendous geometry of the skyscrapers of New York City. You then drive northward, to the green suburb of Chestnut Ridge, NY, to the 148 acre Threefold Educational Foundation... Here, besides our center for eurythmy, is the largest Waldorf School in North America, an elder-care community, Waldorf teacher training, and a Biodynamic training, among others.

“Eurythmy Spring Valley is comprised of the internationally known performing Ensemble and the highly respected School, which offers both full-time and parttime training leading to a variety of careers in eurythmy.

“Human sound carries all of life within it... Though we may not be as aware as our ancestors of this reality, it remains true that the human voice is one of the most remarkable of instruments. It has the capacity to transform our inner experiences into another medium, sound. When the sounds of language and song are intoned, they set into motion, unique, yet invisible gestures through the air. Artistically expressed they reveal the specific gestures belonging to each consonant or vowel, each musical tone or interval. These innate forms living in sound, within our souls and in the world become the basis for the art form of eurythmy.”

summer-fall issue 2016 • 19

From eurythmy.org, the website of Eurythmy Spring Valley.

Barbara Schneider-Serio, Beth Dunn-Fox, Sea-Anna Vasilas, Jana Hawley, Rafael Manaças

2016 Graduates (l-r) CoCo Verspoor, Yen Ling Yeh, Ivilisse Esguerra.

Integral Teacher Education at CIIS

by Robert McDermott

This essay on the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS) and the companion essay on Waldorf education by Liz Beaven together present a vision for the creation of one or more programs in Integral Teacher Education at CIIS, an accredited undergraduate and graduate university in San Francisco. As I wrote in the dedication of my book, Steiner and Kindred Spirits (2015), CIIS is “a university dedicated to integrating the intellectual and academic with a variety of spiritual teachings and practices” (xi). It is worth noting that chapter 9, “Education,” in this book places Steiner’s educational philosophy in a wider context, addressing the relative merits of John Dewey’s, Maria Montessori’s, and Steiner’s approaches to education. In the same spirit, the emerging proposal for a CIIS program (or programs) could be called education inspired by “Steiner and Kindred Spirits,” i.e., an approach to education based on an anthroposophical understanding of human development, the child, curriculum, and pedagogy situated within a larger intellectual context.

CIIS was founded in San Francisco in 1968 by Dr. Haridas Chaudhuri, a disciple of Sri Aurobindo, the preeminent spiritual teacher of 20th-century India. Like Sri Aurobindo, Haridas Chaudhuri based his spiritual philosophy on the yogas of the Bhagavad Gita: spiritual knowledge, love, selfless action—approximately the same triple discipline—thinking, feeling, and willing—recommended by Rudolf Steiner. This triple discipline and approach meets a contemporary need, demonstrated by growth in CIIS enrollment. When I was appointed president in 1990, CIIS had 300 students in two schools. By the time I transitioned from president to faculty in 1999 CIIS enrolled 800 students in three schools. Currently it has 1500 students attending four schools: Consciousness and Transformation, Professional Psychology and Health, Undergraduate Studies, and American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

CIIS has a long relationship to Steiner’s work and a deep affinity with his social ideals. While teaching in the Philosophy, Cosmology, and Consciousness (PCC) program for the past fifteen years I have taught anthroposophy in many courses, including Karma and Biography; Death and Beyond; Steiner and Teilhard; Modern Esotericism; Krishna, Buddha, and Christ; Aurobindo, Teilhard, and Steiner. In a recent issue of being human , five CIIS

graduate students described the close positive relationship between their CIIS education and their involvement with anthroposophy or Waldorf education, or both. Throughout its history, CIIS has attracted many Waldorf alumni. These and other students have been heard to refer to CIIS as “Waldorf for Adults.”

Due to a close alignment of the ideals of Waldorf principles of education and CIIS’s mission statement, the leadership of CIIS is seriously interested in creating a program in teacher education. The CIIS mission statement could serve as a mission statement that fulfills this intention:

California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS) is an accredited university of higher education that strives to embody spirit, intellect, and wisdom in service to individuals, communities, and the Earth. CIIS expands the boundaries of traditional degree programs with interdisciplinary, cross-cultural, and applied studies in psychology, philosophy, religion, cultural anthropology, transformative learning and leadership, integrative health, and the arts. Offering a personal learning environment and supportive community, CIIS provides an extraordinary education for people committed to transforming themselves and the world.

Similarly, an integral approach to education would want to affirm the following Seven CIIS Commitments:

1. Practices integral approaches to learning and research.

2. Affirms spirituality.

3. Commits to diversity and inclusion.

4. Fosters multiple ways of learning and teaching.

5. Advocates sustainability and Social Justice.

6. Supports community.

7. Strives for integral and innovative leadership.

The CIIS faculty and administration recognize the importance of a spiritually-based approach to education as a foundation for the type of individual and social transformation that Rudolf Steiner recommended. In the face of equity and access issues, new demands imposed by the Common Core, changing workplace demands, and a national teacher shortage, there is an urgent need for innovative, enlivened, and effective approaches to K-12 education. A San Francisco university known for the quality of its holistic academic programs, and fully ac-

20 • being human initiative!

credited since 1981, CIIS believes that one solution for social transformation lies in preparing teachers to bring a new paradigm to the diverse modern classroom through integral teacher education.

In recent months, Liz Beaven has served as a link between CIIS and many leaders of the Waldorf school movement. Inspired by the shared ideals of CIIS and Waldorf, the senior administration of CIIS has appointed Liz to explore ways to create an integral approach to modern education, including the image of the human being that Rudolf Steiner placed at the core of Waldorf education. As a former class teacher and administrator of the Sacramento Waldorf School (1991-2012), president of Rudolf Steiner College (2014-15), current president of the Board of the Alliance for Public Waldorf Education, as well as a close observer of the CIIS culture, Liz is making progress researching the feasibility of at least one, and perhaps several, programs in Integral Teacher Education.

CIIS views expansion into teacher education as an inspired extension of its mission, values, and vision in support of the current and projected growth of a wide range of schools founded on the principles of Waldorf education. It plans to offer programs that can contribute to meeting a range of urgent needs. CIIS has the structure to support a new program inspired by the effective principles of integral and Waldorf education, and will be designed to address the challenges facing today’s children, teachers, and schools. Liz has discovered ample evidence of interest in these programs in the San Francisco Bay area, as well as nationally and internationally. A research and design phase of this exciting new initiative will continue through the coming academic year, 2016-17. It is already clear that this is the ideal time for CIIS to appoint a distinguished leader of Waldorf education able to join the ideals of Wal-

dorf education to the intellectual-spiritual ideals of CIIS.

The research and design phase will determine the final structure of programs, based on the identified needs of schools and prospective teachers. Working closely with the CIIS administration and faculty, Liz Beaven is currently completing the initial design work that has included extensive conversations with educators and a comprehensive review of the literature of existing programs in Waldorf, Montessori, and “mainstream” MEd degrees and certificates. Part of this initial work includes the exploration of options for California State Teacher Credentialing, considered important for providing options for employment for future teachers, for widening the spread of this approach to education, and for providing access to an enriched education for a wide range of children.

The following programs are being considered for implementation: Masters of Education; graduate certification in integral education; Bachelor of Arts Completion courses; public workshops for educators. All evidence suggests that CIIS would be an ideal incubator for a program, or programs, in integral education inspired by the principles of Waldorf education and including the perspectives and academic resources of a pluralistic, inclusive undergraduate and graduate university. This new educational paradigm will promote a thorough understanding of child development based largely on an anthroposophical understanding of child development, and will support teachers in their effort to bring renewed creativity, mindfulness, and joy to the classroom.

Robert McDermott, president emeritus of the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS), and CIIS professor of philosophy and religion, was chair of the boards of Sunbridge College and Rudolf Steiner College. His books include The New Essential Steiner and Steiner and Kindred Spirits.

Towards an Integrated Approach to Teaching

By Elizabeth Beaven

Waldorf educators are eagerly anticipating the 100th anniversary of the founding of the first Waldorf school in Stuttgart, Germany, which first opened its doors in September 1919. Plans are underway for celebrations of a school movement that has grown from that first school to global proportions. The extent of this growth was demonstrated by the recent World Teachers’ Conference in Dornach, Switzerland. There, in a kaleidoscope of languages and cultures, over 850 individuals united by their

work in Waldorf education formed a living demonstration of the remarkable fruits of Steiner’s call for a new art of education, one that can positively effect social transformation and renewal.

With the founding of our oldest school, the New York Rudolf Steiner School, the impulse of Waldorf education made its way to North America in 1928. From that time until the early 1990’s Waldorf education on this continent grew quietly as a movement of independent schools. This

summer-fall issue 2016 • 21

slow growth, made possible by the work of many devoted individuals, allowed Waldorf education to generate a distinctive culture and a rich body of practice and research. This slow growth began to shift in 1991 with the opening of the Milwaukee Urban Waldorf School, a public “specialty” school developed out of a social justice desire to offer quality education to underserved inner city children. Since then, the Waldorf educational impulse has spread to public education, largely through the mechanism of charter schools. This spread has occasioned much debate and discussion, and has arguably led to healthy and necessary research and opportunities for continued growth. Questions have abounded: how, exactly, is “Waldorf” to be defined? What is essential in this definition? Why is such definition necessary? How can the integrity of the Waldorf “brand” be protected, ensuring that the essentials continue to thrive? Is Waldorf education even possible in a public school setting? How do we ensure quality in our schools? How do we resolve the tension between the demands, compromises, and opportunities resulting from independence in education (one form of freedom) and the social justice need for access for many to an enlivened education (another form of freedom)?

These and similar questions are being addressed in a number of ways. The Pedagogical Section Council worked to define the “core principles” of Waldorf education—that essential core that makes Waldorf, Waldorf. Their work has led the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America (AWSNA) and the Alliance for Public Waldorf Education (APWE)1 to work to define their own iterations of core principles from the perspective of their schools or institutes in an effort to clarify similarities and differences, with the ultimate goal of strengthening our work, insuring quality and integrity, and allowing Waldorf education to flourish in service of children and of our future.

At this time there exists a broad and expanding spectrum of schools working from Steiner’s indications (which include a developmental framework, a “true knowledge of the nature of the human being,” the imperative of the arts, and the need for integrated connections). This educational impulse is finding new and varied forms in response to a range of conditions. Worldwide and on this continent, there is an expansion into diverse

1 Through an agreement with the BUND, AWSNA is the steward of the terms “Waldorf,” “Rudolf Steiner,” and “Steiner” in educational contexts in North America. The APWE has an agreement to use the term “Public Waldorf”.

cultures, emerging needs, and varied school structures. These encouraging innovations appear to be aligned with Steiner’s original intent of a creative, constantly renewing, pedagogical approach. Viewed from the perspective of this widening spectrum, the old divide of “independent/private” and “public” schools no longer fully reflects a new reality.

No matter the form or location, effective education is profoundly influenced by the quality and capacities of teachers. This is especially relevant in Waldorf education, where teachers are charged with responsibility for pedagogical matters and are expected to continuously renew and reinvent their classroom approach based on the needs of their students and of the local conditions of the school (Tautz, p. 23). There is no comfortable prototype for a Waldorf school or for a Waldorf teacher: rather, there is an imperative of “taking hold of the living impulse of the Waldorf school in a concrete way and bringing it to realization.” (Tautz, p. 23). In remarks made to the original group of teachers before their intensive course of preparation, Steiner emphasized the social, transformative goal of Waldorf education: “From the Waldorf school there should go out a renewal of the whole educational system.” He emphasized the responsibility of the teachers in realizing this goal: “The success is in your hands.”

The first Waldorf school answered local conditions remarkably well and thus grew rapidly. Within six years there were at least six schools in four European countries. During these years, Steiner traveled extensively and gave a number of lectures in which he emphasized and refined his core pedagogical ideals. Reading these, one can sense a growing urgency to “develop an art of education that can lead us out of the social chaos into which we have fallen…. [and] find a way to bring spirituality into human souls through education” (Roots of Education, p. 1)

Addressing the goals of Waldorf education, Steiner continued: “What we are examining is mainly concerned with matters of method and the practice of teaching. Men and women who adhere to anthroposophy feel— and rightly so—that the knowledge of the human being it provides can establish some truly practical principles for the way we teach children.” (ibid , p. 17) He continued: “Moreover, I would like to point out that the true aim and object of anthroposophic education is not to establish as many anthroposophic schools as possible. Naturally, some model schools are needed, where the methods are practiced in detail. There is a need crying out in our time for such schools. Our goal, however, is to enable every

22 • being human initiative!

teacher to bring the fruits of anthroposophy to their work, no matter where they may be teaching or the nature of the subject matter. There is no intention of using anthroposophic pedagogy to start revolutions, even silent ones, in established institutions. Our task, instead, is to point to a way of teaching that springs from our anthroposophic knowledge of humankind.” (p. 18)

While acknowledging the danger of taking any one statement by Steiner as the basis on which to build an argument, these thought-provoking words are relevant to the context of contemporary education. Our schools in general face tremendous challenges, and our young people are confronting an uncertain future and a time of unprecedented change. Children everywhere would surely benefit from an approach to teaching that springs from the wisdom of an anthroposophic knowledge of the human being. A teacher is core to educational success; therefore, effective and conscious preparation of future teachers is essential—for all children.

Emphasis on the development of the individual teacher is possibly the most effective strategy for “taking hold of the living impulse of the Waldorf school in a concrete way” and allowing the impulse of Waldorf education to serve as a source of renewal “for the whole educational system,” Steiner’s stated goal. Preparation for this task includes a thorough knowledge of the true nature of the human being, a body of pedagogical information (Steiner’s “methods and practice of teaching”), and tools for an ongoing process of self-knowledge and reflection that will lead to creativity, renewal, and the ability to respond sensitively to the needs of a particular group of children. Such preparation leaves a teacher in freedom to practice enlivened teaching in any setting across the full spectrum of schools—from private Waldorf schools through varying iterations of charter schools and home schools through the vast array of “mainstream” public schools.

This focus on the individual teacher provides a new definition of education toward freedom; a teacher is free to adopt this approach and is free to practice it in any setting. Freedom can be understood not as the outer structures or conventions of schools, but rather as the ideals and practices alive within each individual. Parallel to this, the impulse of Waldorf education will be increasingly freed to take a more fully integrated role in educational renewal. The Waldorf impulse has much to contribute and can be enriched in turn by interaction with likeminded practitioners.

The recent World Teachers’ Conference sought to place Waldorf education in a broad context with an emphasis on social justice and the demands of the future. It spoke of collaboration, of finding our colleagues in the world, of re-thinking and re-imagining our work in anticipation of a new century of practice. In 1924, Steiner spoke with urgency about the need “to enable every teacher to bring the fruits of anthroposophy to their work, no matter where they may be teaching.” This need is surely even more urgent now. Meeting it will require ever-greater levels of engagement and collaboration with like-minded colleagues, dialogue, willingness to teach—and willingness to learn from others, in service of children and of the future.

References:

Steiner, R. (1997). The Roots of Education. Anthroposophic Press.

Tautz, J. (2011). The Founding of the First Waldorf School in Stuttgart. AWSNA Publications, Ghent NY.

Elizabeth Beaven (lizbeaven@sbcglobal.net) has been a Waldorf educator for more than thirty years as class teacher, parent, school administrator, adult educator, and author. She is currently conducting a feasibility study for CIIS, San Francisco, exploring the development of a new program in integral teacher education. She consults with a wide range of Waldorf schools, public and private, and is the president of the board for the Alliance for Public Waldorf Education.

Thoughts of the Dead

Unrealized ideas of the dead blow like a wind through trees beyond our bed, sprinkle the night with aspirations not our own, and spice our love with the desire of the disembodied. They fertilize our sleep like worker bees, their feet fluorescent with the pollen of another place and time. They perch like birds on the wire edge of our waking singing subliminal songs until we rise and set about doing the work the dead can no longer do.

Maureen Tolman Flannery is the author of Tunnel into Morning , seven other books of poetry, and a chapbook of poems Snow and Roses about Traute Lafrenz Page and her work with the White Rose Society in WWII Germany.

Raised on a Wyoming sheep ranch, Maureen and her actor husband Dan have raised their four children in Chicago.

summer-fall issue 2016 • 23

IN THIS SECTION:

Elaine Upton shares the deep reflections of Shakespeare’s King Lear in a poetic mind of the 21st century.

What does “esoteric” really mean? And in what ways does the Bard of Avon and his four-century-old legacy qualify?

Teacher and writer Bruce Donehower makes the case for and against Shakespeare— something to do with freedom?

Incoming ASA

General Secretary

John Bloom finds money and selfhood to be at an intersection.

Maureen Flannery writes wonderful poems! On pages 23 and 39.

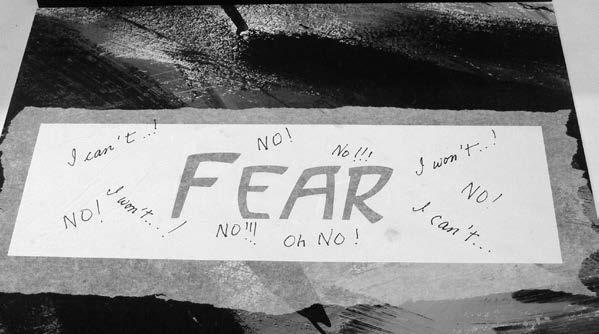

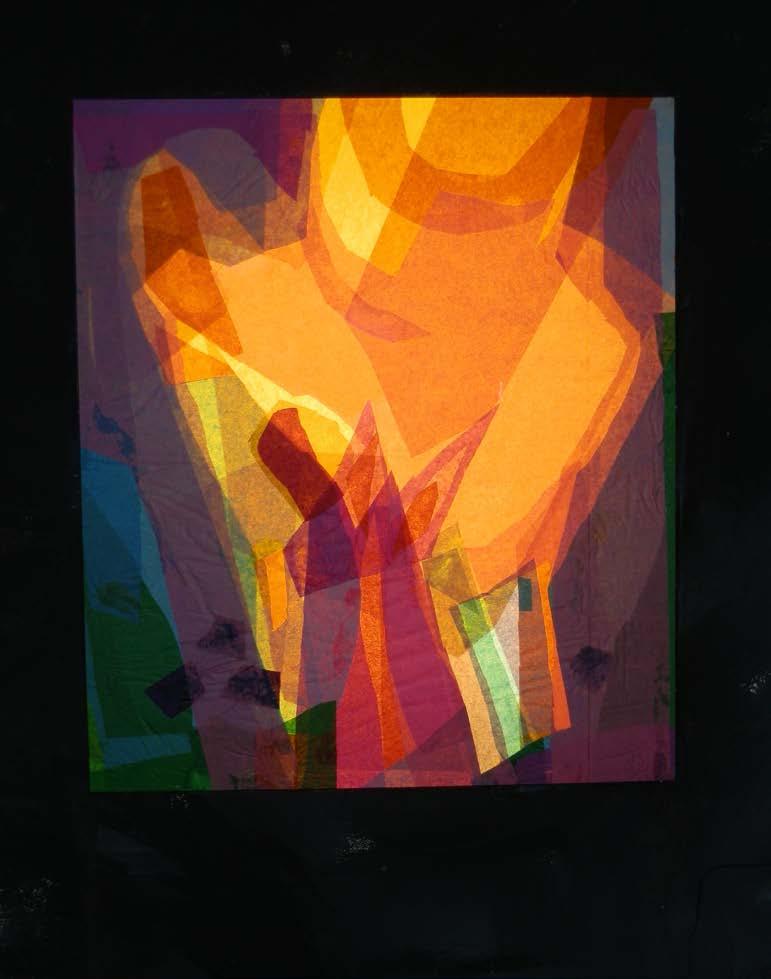

IN THE GALLERY:

Out of Rudolf Steiner’s dream of plays of light came an experiential art installation on how we fall into fear, and come back out. This paper presentation lacks the full power of the original, but seems well worth sharing!

The Lear Elegies

by Elaine Maria Upton

1.

Up—early or late—on the staged edges of things— at the hovel and in the sold-out house the lights already out. The trafficked sky—piqued-pink a rose dying and violet half-hidden lightning blue silence at the last twilight, a fumbling thunder of his thoughts— all this he nakedly overtakes, severely testing the ages, sight, might of tongues. We are—a priori— to know: he sat encumbered on a throne, gave away a kingdom. We are entering the apparent ending whose burly banner is hope— whose goal is greatness—and all the scened and unseen shapes that court kings: daughters, princes, serving men, earls, dukes soldiers, charters, waning trade, wives, an assortment of wars, haunted hovels he would visit, speech that heats and inherits lust, milk uddered from the mind’s slippage, fright deeper than midnight—fools’ cacophony, discourse that renders ‘casualties’ of causes, counters birth, collects coffins, buries queens, checkmates the breaths of children.

2.

The Earl of Gloucester—brutally blind—begged to be led to Dover. Wherefore to Dover? asked the masked Poor Tom. Any fool could answer: Dover rhymes with over and death. The sea’s wall makes a chalky ghost— mists ‘twixt Britain and France are where lover, madman, king-made-fool— and Macbeth making poetry with despotic dagger—meet. Where Nothing appears and seems the rule. Imagination disguised in blood or dressed in rags puts on the hollow crown. This is no kingdom but a stage of naked wretches the king—orating—owns.

3.

What shall come of all this that passes for life? An antiquated or an august anguish? An unsuspected catharsis spiraling in and out past the storm? Pythagoras reclaiming numbers? Three weird siblings, barren bosoms, gone beastly: Goneril, Regan, Edmund. Three—Poor Tom o’ Bedlam, Kent, Cordelia. These are in exile, disguised or nothing at all— as though Nothing were inside a choice and truth a dowry a daughter or friend could give. Lear and his fool play the zero in-between the darkened threes of branches, or zero disguises Cordelia’s heart—the encompassing O—sign of her name, her name a globe where the devil’s nothing is everything, womb-bearing word, poetry of a palpitating— center penduling between progressing angels and the slow Earth. Past time, poetry moves— moistens the eyes of virtue, hoarsens the throat of the antagonist— who of us can cast a stone?— and the racked rogue’s on a roundabout to repentance—then or now.

Is it possible?

A designer of Auschwitz sees his face in the cruel blueprint of things. There is no hiding place. After thirty-eight years of the discarded angel, he walks out of the wings. Who remembers? Is it possible? The frightened policeman in the U.S. city sits lonely with his guns. Turns the smart phone to off. Is it possible? The would-be bomber ponders at his mother’s grave in Paris at Per La Chaise.

24 • being human

arts & ideas

Poetry ponders un-ponderously. Poetry undresses— unwords itself— unspools the life-lines—be-leaps the strings, arpeggiates the scales-- listens to itself in every self—dies into the silence—discovers possibility—creates what it wills.

Say—as though your way were dedicated and brave: I will be led unclothed to Dover. As though you were taught the thought and vision of a god—say: I have other meat to eat. Thy kingdom come. I would be led into the Mysteries of things. Thy will be done. Say: in poetry, the dovely magic of Jordan.

Beg your daughters not for soldiers, nor for bread, but gently inquire of a pillow for your death. At least one of them will meet your silenced howl, your foolish love. And the one—perhaps even another, lost—will grieve. Love is only what it only can be. What it must. Such is poetry.

4.

Four hundred years later—or who knows how long his hour on the stage-time out of joint—who knows how long or how suddenly folded-short the calendar?—a friend asked Where is Christ in all this? In Lear they swear by Juno or Apollo, the god who never stays put on poets’ pages. Yet who but Christ enters Cordelia’s passion, Lear’s repentant suffering?

Christ is a name for all things countering strange transcending things. Imagination remakes—purely—who we would be— created of nothing. Even Macbeth struts and frets his nothing and in disordered fantasies proclaims he’s murdered death and then assumes he’s heard no more. Nothing is generative. Have pity on the king who prays Never, never, never . . . Such words on and on do but seed ever. Endurance? Why not? —beyond the final scene—

Four hundred or forty –our experience in the wilderness confounds time again. Over and over . . . Daughter-fool-father-mother—confounded. King becomes Mother—heaven’s keeper and queen. So it must be. So it must be. This my heart’s necessity.

5.

Four hundred years or thirty or three—depending on how and not what your heart would hear and see. Each may presume to be inscrutably alone—each in the seeming suffers. Yet even then in the act of presuming no one is there— some Madonna and Child, some Pieta appears and teaches: If there’s one there’s another—Imagined, whether greatly or little. Schionatulander still listens at Sigune’s heart. So it must be and the artist must sing. Isolde’s throat trembles in Tristan’s ears. Begging, she births his gentle smile. And Lear—even his unhoused mind must still

summer-fall issue 2016 • 25

dwell in possibility.

He makes a hearth of enfolding arms. and whisperingly he asks—

Cordelia, Cordelia, stay a little.

You may author the unsung scene where she and he — this once-then-unclothed-king-turned-mother— sing as two birds in their gilded cage. You may see him prepare a table he— a wayward father has never yet prepared. He makes a sacred altar where the choler— his readied sulfur—combusts. And here he dares what he must. His heart—in hers—and ours in his—finds its abyss and breaks.

Elaine Maria Upton is a Shakespeare scholar and an awardwinning poet with extensive experience teaching in South Africa. She is an associate editor of being human and has contributed a book review, poems, and reflections.

Shakespeare and The Esoteric

by Frederick J. Dennehy

Is there esoteric meaning in Shakespeare?

We could try to select or formulate an esoteric principle and show how it inhabits the plays. But then, after seeing the plays again, I suspect that we would find that principle inadequate, and either struggle to redefine it, or give up explaining the plays esoterically altogether.

Esoteric meaning is fresh, new meaning before it becomes a mental habit, a possession, something for the ego to devour.

I think there is light to be shed, but it comes from the other direction. There is esoteric meaning in Shakespeare. Rudolf Steiner said that all genuine art is a reflection of the human experience of the divine. That means that Shakespeare, the most genuine of artists, can light up our understanding of the esoteric. The Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges said that Shakespeare was “everyone and no one.” He worked in the mystery of language better than anyone before or since. His art has been described by the scholar Harold Bloom as “so infinite that it contains us ; we don’t read his plays so much as they read us.”1

Shakespeare created meanings. He worked from inspiration to imagination, and from imagination, through explicit or implicit metaphor, to new meanings. Inspira-

1 Harold Bloom, Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human (Riverhead, 1999), p. 27.

tion grasps what was not grasped before, and imagination makes new cognition comprehensible by relating it, not reducing it, to what is already known.

Esoteric meaning is fresh, new meaning before it becomes a mental habit, a possession, something for the ego to devour. Meaning “happens” in the changing from one plane of consciousness to another in the movement itself, in the metamorphosis. That “becoming” always takes us closer to the Origin, or the Source, before things are divided into subjects and objects. As Owen Barfield has said, there is “a very real sense” in which many of the thoughts and feelings that we have today were once meanings that Shakespeare brought into being.2 In fact, some that have already passed from fresh meaning into habit, into our most common expressions, were first Shakespeare’s inventions.

While Shakespeare represents human nature more universally than any other writer, his characters are so individual that we often feel we know them better than we do some of our friends. There are dozens that we recognize as themselves after only a few lines. Characters in most plays are definite personalities, and they simply unfold as we watch them In Shakespeare, character becomes. It is alive. In the mature soliloquies, for instance,

2 Owen Barfield, Poetic Diction: A Study in Meaning (Wesleyan, 1973), p. 137.

arts & ideas

26 • being human

Study for The Death of Cordelia, detail of a sketch by George Romney (1734-1802); Folger Shakespeare Library

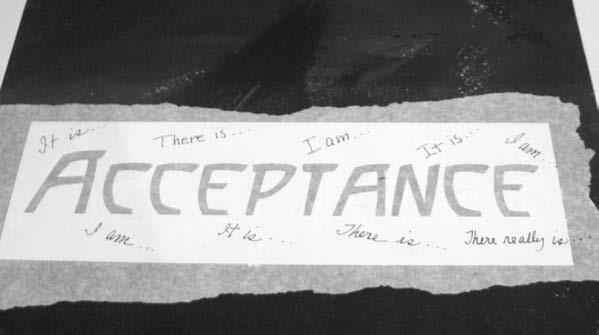

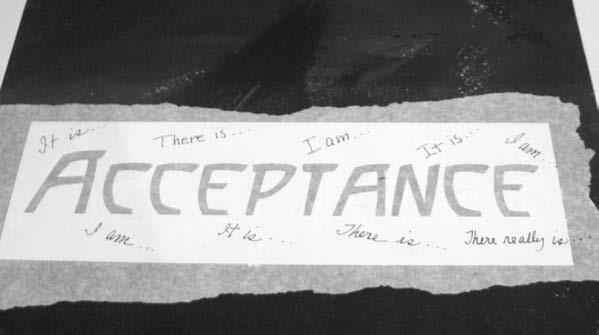

Gallery: Metamorphosis of Fear: An Exploration

Elizabeth Lombardi

Elizabeth Lombardi

In this twenty-foot installation of five illuminated windows of translucent paper, a holding structure of black and white (above) describes how an individual perceives the dynamics of his or her surroundings: