being human

personal and cultural renewal in the 21st century

Idea, Theory, Emotion, Desire (p.30)

Free Columbia –Spiritual Activism (p.18,33)

Review: The Impulse of Freedom in Islam (p.46)

Steiner, Nietzsche, and the Adversary (p.40)

a quarterly publication of the Anthroposophical Society in America

issue

anthroposophy.org

spring

2015

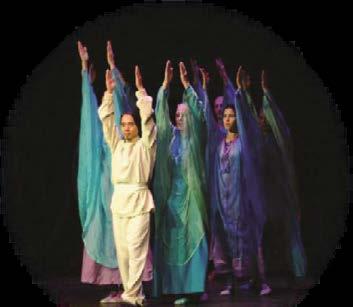

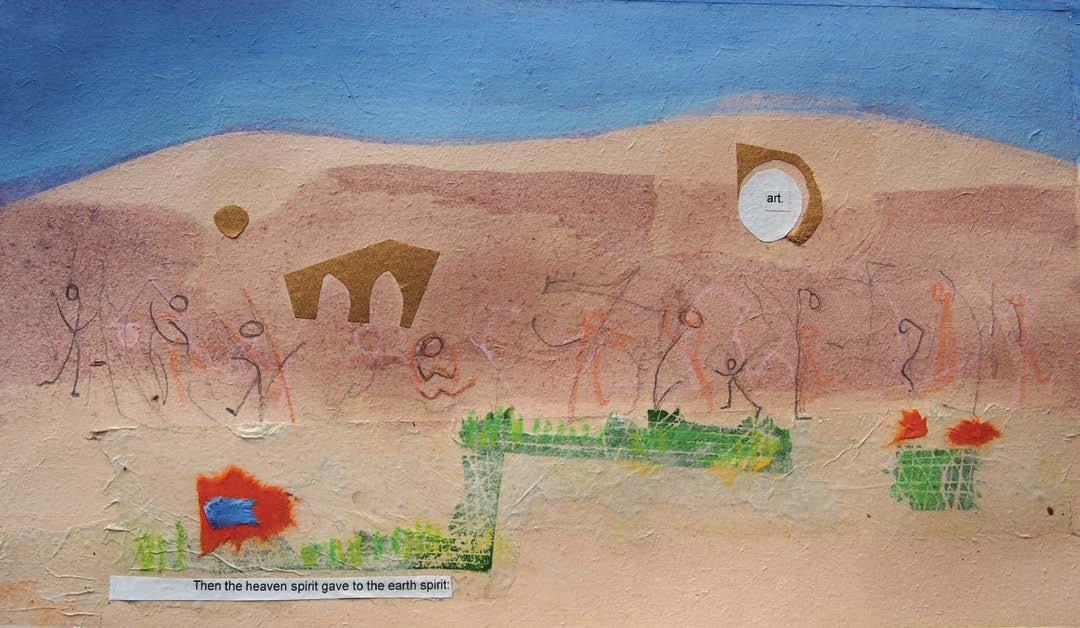

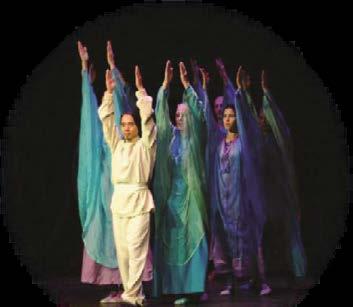

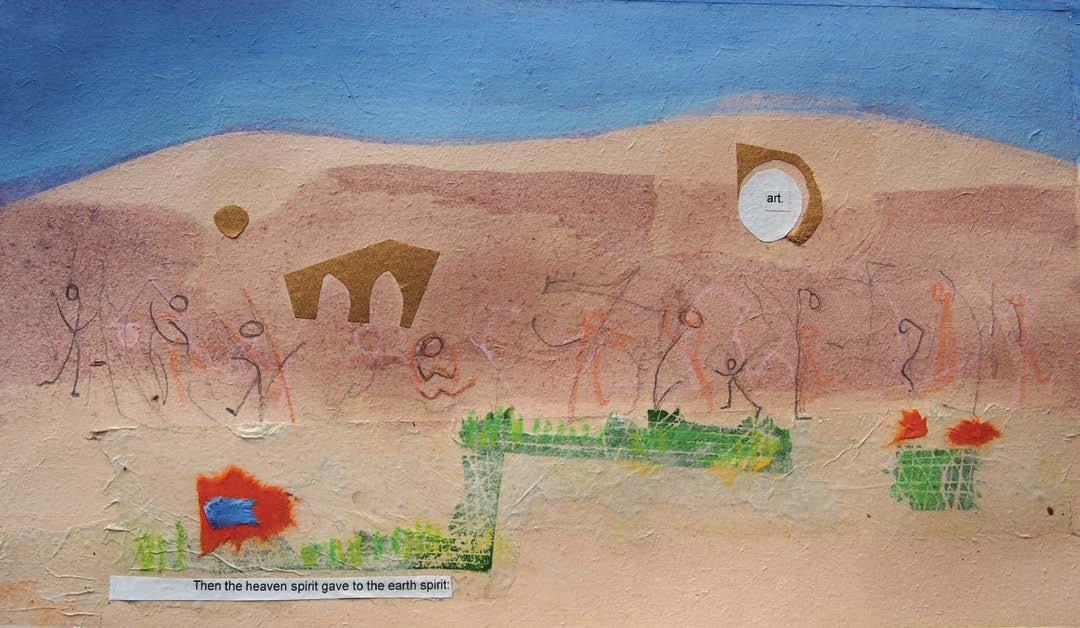

“Resolution” by Laura Summer

Find Christ in a New Way

The Christian Community is a worldwide movement for religious renewal that seeks to open the path to the living, healing presence of Christ in the age of the free individual.

All who come will find a community striving to cultivate an environment of free inquiry in harmony with deep devotion.

Learn more at www.thechristiancommunity.org

D.N. Dunlop: A Man of Our Time

D. N. Dunlop (1868–1935) combined remarkable practical and organizational abilities in industry and commerce along with the gifts of spiritual and esoteric capacities. His life was changed forever when he met Rudolf Steiner—an encounter that “brought instant recognition.” This enlarged second edition features substantial additions of new material and an afterword by Owen Barfield.

ISBN 978-1-906999-66-7 | 436 pages | paperback | $55.00

Ludwig Polzer-Hoditz: A European

Thomas Meyer’s major biography of Ludwig Polzer-Hoditz (1869-1945) offers a panoramic view of an exceptional life. This is a pioneering work in biographical literature, structured in four main sections that reflect the stages of an individual’s personal development. This first English edition is based on the latest German version and features additional material and 64 plates.

ISBN 978-1-906999-64-3 | 728 pages | paperback | $70.00

The Development of Anthroposophy since Rudolf Steiner’s Death

This important book offers profound insights into the struggles for individual freedom and voice during the early years of the Anthroposophical Society. Seeing the dynamics of that struggle can help us today to overcome differences to work toward common purpose, both in the context of our everyday lives and within a spiritually oriented community.

ISBN 978-1-62148-116-4 | 256 pages | paperback | $22.00

SteinerBooks | 703-661-1594 | steinerbooks.org

May 7 to May 17, 2015

Miami, FL Wilton, NH

New York, NY Spring Valley, NY Great Barrington, MA

Visit steinerbooks.org for details

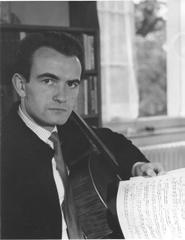

T. H. Meyer was born in Switzerland in 1950. He is the founder of Perseus Verlag, Basel, and is editor of the monthly journal Der Europäer He has written numerous articles and is the author of several books.

Meyer’s East Coast Lecture Tour

Marcus Knausenberger

Thomas

Save the Date

6 6

Resources for the conversation about humanity’s future...

“If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.” –Thomas Jefferson to Charles Yancey, Jan. 6 1816

Jefferson wrote out of concern for a young nation’s political liberty. Today we face the challenge of creating, as Rudolf Steiner said, a future worthy of the human being.

Generations after Jefferson and ninety years after Rudolf Steiner’s death, in an age of marvels that challenges our humanity and casts a shadow on our future, what can be the role of a library for anthroposophy?

Making the work of Rudolf Steiner and others in this human-centered stream of living, caring, purposeful thoughts available—that has been a core goal of the Anthroposophical Society in America, involving translating, sharing typescripts, publishing, and creating the national Rudolf Steiner Library

From its long-time home on Madison Avenue in New York City, through its three decades in the Berkshire-Taconic region, the staff of the Rudolf Steiner Library have built an intellectual jewel—the single largest collection of anthroposophical works in English in the world. It embraces also the broader heritage of philosophical, religious, artistic, cultural, and sociological thought from throughout history: the rich context for anthroposophy’s research into humanity’s past and future. This combination opens up a dynamic conversation between anthroposophy and the world.

Moving forward again.

A new future for the Library has opened through the focused work of the library steering group, the national council, the Berkshire- Taconic community, and trusted advisors.

Protecting the past.

Care for the collection has started. New archives and rare materials are coming to light. Cultural heritage is being preserved.

Engaging the future.

A plan to digitize the journals is moving forward. Plans for expanded online discovery and access for both the archives and the collections are in the works.

Building a library network.

Linking collections around the country, establishing a national service center in the Hudson Valley, and developing a complementary home for research & archives at the Rudolf Steiner House in Ann Arbor.

Partnering for depth & impact.

Reaching out across the movement— Waldorf, Camphill, biodynamics, health, social action—to deepen special collections. Working to expand access to works in English worldwide.

Giving back to anthroposophy.

The initiative of individual human beings is where anthroposophy is constantly renewed. The Rudolf Steiner Library will continue to strengthen research and study, nourish our love of community, and inspire the wisdom for action.

We’d love to share our latest plans with you. Visit us online: www.anthroposophy.org/rsl or call 734.662.9355 to join our mailing list.

Rudolf Steiner Library Moving Forward

Upcoming Webinar

The Human Encounter: Parent-Teacher Relationships in a Waldorf School Community A Conversation with Torin

M. Finser, PhD

M. Finser, PhD

A school is a community, and like all communities its health depends upon the quality of its relationships. Joins us as Torin speaks to the parent-teacher relationship in all its dimensions o ering both practical advice and deeper, spiritual insights.

Tuesday, April 21, 2015 2:00 – 3:00 p.m. ET Visit anthroposophy.org to register!

This webinar is co-sponsored by AWSNA and the Anthroposophical Society in America

•

BIODYNAMICS is a holistic approach to agriculture, food production and nutrition that brings health and vitality to the soil, plants, animals and humanity. Join the gardeners and farmers who are using biodynamics to turn their land, whatever its size, into a work of art, overflowing with life forces, diversity and vitality.

Inspiring Waldorf

Teacher Education

Waldorf

Professional

Courses

Since 1967 Low-Residency Elementary & Early Childhood

Teacher Programs •

Development

& Workshops

Introductory Experiences &

NOW REGISTERING / ENROLLING www.sunbridge.edu

Waldorf Weekends

us in Rethinking

www.biodynamics.com Join

Agriculture

12 Validating Medical Remedies: Renewing the Research, by John Beck

18 Free Columbia: Spiritual Activism, by Laura Summer

20 Can Eurythmy Live Online, by John Beck & Cynthia Hoven

23 The Present Age, T.H. Meyer interviewed by John Beck

25 Deeds that Matter, by Christopher Schaefer

30 Idea, Theory, Emotion, Desire, by Frederick Amrine

33 Gallery: Free Columbia

38 Understanding the Imponderable in Nature, by Barry Lia & Science Section 40

40 Rudolf Steiner’s Meeting of Destiny with Friedrich Nietzsche and the Adversary of Our Age, by C.T. Rozell 46 The Impulse of Freedom in Islam, a review by Elaine Maria Upton

Rudolf Steiner: The Man & His Vision, a review by Fred Dennehy

51 Three Poems, by Maureen Tolman Flannery 52 Threefold Auditorium Renovation, by Bill Day

initiative!

Contents 12

30 arts & ideas

research & reviews

49

news for members & friends 53 2015 Organizational Goals 53

from

León

56 General Secretary Torin Finser Visits 56 Introducing Micky Leach 56 The Grail in Phoenix 57 Members Who Have Died – New Members

Martina Mann,

Laura Liska

53

Report

Marian

55 Transformation & Gratitude, Report by Deb Abrahams-Dematte

58

by

58 Georg Locher, by Adrian Locher & Torin Finser 62 Thinking About Thinking, by Paul Margulies

62 A Memory of Paul Margulies, by Maria Ver Eecke 63 Calendar of the Soul – 2014-2015 Dates, by Herbert O. Hagens

The Anthroposophical Society in America

General Council Members

Torin Finser (General Secretary)

Virginia McWilliam (at large)

Carla Beebe Comey (at large)

John Michael (at large, Treasurer)

Dwight Ebaugh (at large)

Dennis Dietzel (Central Region, Chair)

Joan Treadaway (Western Region)

Marian León, Director of Programs

Deb Abrahams-Dematte, Director of Development

being human is published four times a year by the Anthroposophical Society in America

1923 Geddes Avenue Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1797

Tel. 734.662.9355

Fax 734.662.1727

www.anthroposophy.org

Editor: John H. Beck

Associate Editors:

Fred Dennehy, Elaine Upton

Design and layout: John Beck, Ella

Lapointe, Seiko Semones (S2 Design)

Please send submissions, questions, and comments to: editor@anthroposophy.org or to the postal address above, for our Summer 2015 issue by 4/10/2015.

©2015 The Anthroposophical Society in America. Responsibility for the content of articles is the authors’.

from the editors

First a correction. In our last issue, in connection with Bruce Donehower’s review of Spiritual Resistance by Peter Selg, we placed a photograph of psychiatrist and anthroposophical leader F.W. (Frederik Willem) Zeylmans van Emmichoven (1893-1961) where the text was speaking of the work of his son, the Dutch physician and biographer of Ita Wegman, J.E. Zeylmans van Emmichoven (1926-2008). We received a correct photo from Jannebeth Röell, who also appears in this issue in a report of the Science Section meeting last fall in Portland, Oregon.

Welcome, Teachers!

Usually we get to talk here about what enthuses us in the content of a new issue, but this time we are enthusiastic about some new readers. Perhaps as many as a thousand teachers and others involved with Waldorf schools will be receiving this issue. We are delighted to have you with us, we know you already have a great deal of work to do preparing fresh, living, personalized meetings with young people and can’t possibly do all this extra reading right now—but, when you have a chance, please take a look. Perhaps just the couple of pages of the digest that follow immediately. Or anywhere else. And let us know what you think, candidly! We love new readers just as much as the loyal readers of several years, who first saw “being human” as a 150th birthday present to Rudolf Steiner.

So what about the contents? “Holistic.” Anthroposophy could be called a holistic anthropology, or a holistic humanism; but important words get turned into pressed sawdust, “buzz words,” and the meaning is sent away. Holistic is what a Waldorf teacher aims to do with each child: see her or him entire, whole, and yet in flow, in process.

Our contents are aiming at this same sort of goal, and while it’s quite impossible to reach, the attempts can be invigorating. There are many things in this issue which make an editor happy. We have a great collection of “initiatives” (though each item in each section could be in at least one of the other sections—that “holistic” thing, again). Great initiatives, the will of healthy people to do whatever they can, to be the changes the world needs, to meet the future with open arms.

Wonderful ideas! A Fred Amrine essay takes close attention, but it brings us so often that experience Rudolf Steiner pointed to: the birth of a new idea into one’s own consciousness. There, Dr. Steiner pointed out, something happens which is of the essence of human being and becoming. And if you don’t quite know why, go all the way to the back, page 62, where we reprint a poem, prefaced by a bit of Steiner, which Paul Margulies sent to us in 2011.

HOW TO receive being human, contribute

Copies

Sample copies are also sent to friends who contact us at the address below. To contribute articles or art please email editor@anthroposophy.org or write Editor, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48104.

6 • being human

of being human are free to members of the Anthroposophical Society in America (visit anthroposophy.org/membership.html or call 734.662.9355).

Johannes Emanuel Zeylmans van Emmichoven

It’s a humorous poem from the Alka-Seltzer ad man, beloved author of “plop plop, fizz fizz” and “I can’t believe I ate the whole thing!” Here Paul shrewdly takes us laughing up to that final moment of realizing that thinking properly is not cold but supremely warm, an act of love.

I could say more about this issue, mentioning for instance the three fine poems by Maureen Tolman Flannery on page 51, or the three biographical sketches by Christopher Schaefer (page 25); but now I’m just delaying you from reading it.

So welcome, new reader, and welcome back, old friend!

John Beck

John Beck

In this issue we present two reviews which, in very different ways, we hope are timely. Elaine Upton reviews The Impulse of Freedom in Islam by John von Schaik, Christine Gruwez and Cilia ter Horst, with a Foreword by Abdulwahid van Bommel and an Afterword by Ibrahim Abouleish, translated by Philip Mees. Among matters explored in this book, from a variety of viewpoints, are the meaning of “freedom” in Islam, and the question of whether and how the peoples of the NorthWest and the Islamic East can meet together in a “field of knowing.”

In the light of two magnificent biographies of Rudolf Steiner by Christoph Lindenberg and Peter Selg that have recently become available in English, I have reviewed a much older, non-scholarly biography by Colin Wilson aimed at a wider audience. The review seeks to assess an image of Rudolf Steiner that may still have currency in today’s world.

Dennehy www.starflower.com 888.262.5424 star@starflower.com Skincare Company Living The You’ve Never Seen or Felt Before Vitality... Call or email for a FREE sample A Green Company in business since 1994 Live Enzymes • Live Vitamins & Amino Acids Live Essential Fatty Acids unlike the cooked, denatured or cosmetic grade variety Not only paraben free... completely chemical free. Raw & Food Grade

Frederick

being human digest

This digest offers brief notes, news, and ideas from a range of holistic and human-centered initiatives. E-mail suggestions to editor@anthroposophy. org or write to “Editor, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI, 48104.”

SOCIETY “Crowd Funding”

What do you do when you have a creative idea but lack the funds to develop it? Or you’ve proven a concept and want to put it into action? Or a friend or colleague is in need of medical funds? Or you’re young and can couch surf but can’t afford an plane ticket to this great gathering on the other side of some ocean?

Whatever its possible downsides, the internet as we know it began as a way to help share resources. (An internet “address” is a “URL” or “universal resource locator.”) And connecting up people to share resources in support of a project is now a common thing. When it’s information or ideas the term is “crowd sourcing”; when it’s financial support the term is “crowd funding.”

There are many websites ready to help you do it. Kickstarter.com is an early leader and “kickstarting” is another term for crowd funding. Many concerns of professional fundraisers like “donor fatigue” are becoming common with creative activists. “Hey guys—thought you might be interested in the kickstarter I’m working.... Don’t get too excited and spread it all over the world and wear out all your contacts (though a little would be fine ;) because I’m going to be sharing [another] kickstarter with you in a month and looking for some love and support!”

In the anthroposophical world where for every one person there are perhaps two-and-a-half initiatives, there are now “kickstarters” and “crowd funders” going along quietly all the time. Here are a few, not with our specific endorsement but as examples of the type:

Matre (Matt Sawaya), an anthroposophically inspired rap artist, has just successfully gotten $12,000 to make a professional video of his song “Listen” about LA school district security officers receiving military hardware [short URL: http://goo.gl/5oSjd8].

Friends have started funds to help with cancertreatment expenses of forms-researcher Frank Chester [ww.gofundme.com/h7m29o] and lazure master Robert Logsdon [www.gofundme.com/RobertLogsdon].

Eurythmist and social activist Truus Geraets started a drive helping the Lakota Waldorf School, which cannot survive without donations, to build a first classroom in traditional Native American “Tipi” style architecture [ www.gofundme.com/g5n4ig ].

The San Diego branch newsletter reported on Truus’ effort, with URL, which along with emails and Facebook page posts and likes is how this all spreads!

Free Columbia, profiled in the initiative! section and in this issue’s Gallery, will include crowdfunding in their advanced effort March 18 to April 26 to “pay forward” the upcoming year. Students will then be given their course freely and asked to help fundraise and pay forward the following year. Their multi-pronged campaign will end with a free culture celebration with performance by Matre and an “art dispersal” on April 25/26 in Philmont, New York [www.freecolumbia.org ].

Anthroposophical Society in America—a pioneer in this field—has long received earmarked donations for the North American Sections of the School for Spiritual Science. Currently the Youth Section is seeking funds to send several young high school graduates to the Connect Conference in Belgium [www.anthroposophy.org ].

There is the usual caution: know who you’re dealing with. Understand whether no one pays unless the whole goal is met, or all gifts are final and passed on at once.

And if you’re planning a kickstarter, you might go to TechSoup.org whose technology resources for non-profits include helpful discussions relating to this area.

8 • being human

s o p h i a s h e a r t h . o r g 7 0 0 C O U RT S T , K E E N E , N H 0 3 4 3 1 T h e t e a c h e r o f t o d ay n e e d s c o u r a g e , c l a r i t y, w a r m t h o f h e a r t , a n d a fi r m ly g r o u n d e d c o nv i c t i o n t h a t t h e wo r l d i s g o o d J o i n u s i n a wo r k s h o p o r o u r S u m m e r Institute that you can better tend the b e a u t i f u l g a r d e n t h a t i s t h e f a m i ly.

The Early Childhood Teacher Education Center at Sophia’s Hear th

being human digest

HUMANITIES North American Ordination

On Saturday, March 14th the Christian Community we will celebrate an ordination service in Spring Valley, New York. This small, worldwide “movement for spiritual renewal” is unique in that its founders sought guidance from Rudolf Steiner in the 1920s. This ordination is a milestone because the candidate, Lisa Hildreth, will be the first person to complete her whole training at the North American Seminary. “This has been our goal from the founding of the seminary in 2003, and we expect this to be a full training for future priests both here and for other countries around the world,” writes Rev. Oliver Steinrueck.

The ordination will be prepared by a five-day “open course” of the Seminary, “From Priest Ordination to Priesthood,” from March 10 at 8:00am to March 15 at 5:00pm. Contributors include Rev. Bastiaan Baan, director of the Seminary, and from the leadership in Berlin the Rev. Vicke von Behr, Christward Kröner, and Anand Mandaiker. Themes of the course include priesthood: origins, development, contemporary priesthood; prayer and meditation in daily life; the sacraments’ significance for the spiritual world, for humanity, for the Earth; and priest ordination in the development of Christianity: continuity and renewal. For information and registration contact: Link: www.christiancommunityseminary.org/events/

MEDICINE Holistic Approach to Autism

The co-founder of the New York Open Center, Ralph White, has observed of Rudolf Steiner that his is “the most impressive holistic legacy of the 20th century.” But what is “holistic” anyway? Steiner himself spoke of the need to see things from many points of view, and a powerful example comes where health and education meet.

A monthly international magazine for the advancement of Spiritual Science

Symptomatic Essentials in politics, culture and economy

Order form

❐ Single issue:

CHF 14.- / $ 15.- (excl. shipping)

❐ Trial subscription (3 issues): CHF 40.- / $ 43.- (excl. shipping)

❐ Annual subscription with air mail / overseas: CHF 200.- / $ 214.- (incl. shipping)

❐ Free Sample Copy

Please indicate if Gift Subscription – with Gift Card. The above prices are indicative only and subject to the current exchange rates for the Swiss Frank (CHF).

For any special requests, arrangements or donations please contact Admin Office.

Name:

Delivery Address:

Tel./E-mail:

Invoice to (in case of Gift Subscription):

Date:

Signature:

E-mail: PASubscription@perseus.ch

Phone number: +41 (0) 79 343 74 31

Address: Drosselstrasse 50, CH-4059 Basel

Skype: ThePresentAge

Website: www.Perseus.ch

Perseus Verlag Basel

spring issue 2015 • 9

Ask for free sample issues, also to help us reach out to others who might be interested and/or subscribenow.

NEW

The Christian Community’s Lisa Hildreth

being human digest

A program on “Holistic Approach to Autism” will be given April 25th in Scottsdale, Arizona with Waldorf remedial expert (and long-serving national council member of the Anthroposophical Society in America) Joan Treadaway. Presented by Holistic Special Education, the Association for Healing Education, and the Arizona Council for Waldorf Education, for parents, caregivers, therapists, and teachers, the gathering will discuss what can be done to accompany and support children who are revealing behaviors that are referred to as “autism spectrum disorder.” The conference will focus on Asperger’s and mild to moderate autism. Joan will give an illustrative story to enrich understanding of these conditions, and there will be exploration of therapeutic activities—rhythm, routine, play, imitation, movement, pressure, touch, quiet time and body awareness—while emphasizing the child’s strengths and gifts.

The holistic view does not incline so much to seeing experts “fixing” symptoms. As Steiner put it, “Our rightful place as educators is to be removers of hindrances. Each child in every age brings something new into the world from divine regions, and it is our task to remove bodily and psychical obstacles out of the child’s way, to remove hindrances so that the child’s spirit may enter in full freedom into life.”

Link: HolisticSpecialEducation.org

WALDORF EDUCATION

School Books on Life-Changing Journeys

Rudolf Steiner is one of the most translated authors in history, not too far behind Moses and Mohammed. There is a global interest in education today, but Steiner’s own guidance was often given in specific working situations. Contemporary books are important to introduce the field.

One of the most popular is School as a Journey: The Eight-Year Odyssey of a Waldorf Teacher and His Class, by Torin Finser. The fact of a teacher accompanying a class for eight years is one of the more striking contrasts in the Waldorf approach, and it gives both a natural framework for insights about education and the opportunity to be practical and direct. Dr. Finser has gone on to lead the education program at Antioch University New England, serve as General Secretary of the Anthroposophical Society in America, and write several more books. But this early book still finds new friends. It has had a second edition in Mandarin and has been translated into Farsi, language of Iran, spoken by a hundred million people.

Leila Alemi, the translator, writes that “Waldorf education has been pretty unknown in Iran but very recently, I hear among pioneers of educational reforms in my home country that they are interested to know more. Unfortunately there are few reading materials about Waldorf education in Farsi. I deeply hope Waldorf education can gradually find a new other home in the heart of Middle East and serve Iranian children and families.” Torin explains that “Leila grew up in Iran during the war years. As a result of the suffering she experienced, she began to write healing stories for children. That lead her to a variety

10 • being human

What’s new from WECAN Books? Resources for working with children from birth to age nine and beyond store.waldorfearlychildhood.org 285 Hungry Hollow Rd, Spring Valley, NY 10977 845-352-1590 info@waldorfearlychildhood.org www.waldorfearlychildhood.org

Artist: Leslie Walker

being human digest

New First-Year Full-time Course

Begins September 2015

Full Details available now

The New York Branch of the Anthroposophical Society in America

138 West 15th Street, NY, NY 10011 — (212) 242- 8945

—NY Open Center co-founder Ralph White on Rudolf Steiner

RUDOLF STEINER BOOKSTORE

Open 7 days: Sun-Mon-Tue-Wed 1-5pm; Thu 10am-5pm; Fri-Sat 10am-8pm

soundcircleeurythmy.org

of spiritual questions and then finding anthroposophy on the internet. Despite many obstacles, she found books on Waldorf education and eventually succeeded in making it to New Hampshire, where she completed her degree this past year. She hopes to go back to Iran and start a Waldorf school after completing her internship in Ann Arbor.”

Other translations? Torin recalled that “the most noteworthy story occurred some years ago when a group of mothers and fathers gathered in Soul, South Korea, to work on a translation of School as a Journey. They met once a week in various living rooms, working through the book chapter by chapter. When they were done, they pooled their resources and published the book in Korean. There was a splendid celebration and conference.

“One philosophical thought: in a world ever more divided by religious, cultural and political differences, Waldorf education, biodynamics, Camphill and the other initiatives arising out of anthroposophy become ever more important as a unifying agent for global consciousness and striving for the universal human. The old ways do not work anymore, and people all over the world are looking for fresh ideas. Translating Rudolf Steiner and related authors must be a top priority if we are to reach those, such as Leila, who are seeking but have not had access to helpful material. If we can build an international coalition of spirit-seekers who act locally but think globally, we can begin to affect the flow of events. The world needs the insights of anthroposophy! I urge our readers to support the quiet, often unassuming midwives of cultural renewal, our translators, and the actual publication of small editions that might not ever appear on a best-seller list, but often prove to be a turning point in a person’s biography.”

REGULAR PROGRAMS & ACTIVITIES

WORKSHOPS TALKS

CLASSES STUDY GROUPS

FESTIVALS EVENTS EXHIBITS

visual arts

eurythmy

music

drama & poetry

Waldorf education

self-development

spirituality

esoteric research

evolution of consciousness

health & therapies

Biodynamic farming

social action economics

UPCOMING EVENTS & OFFERINGS

ANTHROPOSOPHY & YOGA

David Taulbee Anderson, Wed 7pm, 4/15, 5/6, 6/10

MONTHLY EURYTHMY with Linda Larson, Mon 7pm, 4/13, 5/11, 6/8

RELATIONSHIPS IN OUR TIME with Lisa Romero, Wednesday, Apr 1, 7pm

PASSOVER SEDER/LAST SUPPER

Thu Apr 2, 7pm, Phoebe/Walter Alexander, Joyce Reilly

LISA ROMERO ON EASTER WEEKEND

“Inner/Outer Biography & The Easter Mysteries”

April 3-5: Fri eve, Sat day, Sun afternoon (Easter)

PUPPETRY WORKSHOP

Sat/Sun Apr 11-12, Nathaniel Williams/Emma Watson

THOMAS MEYER LECTURE

Wed May 13, 7pm - Topic tbd

WEEKLY & MONTHLY STUDY GROUPS

spiritual, therapeutic, world & ‘outsider’ art

spring issue 2015 • 11

ANTHROPOSOPHY NYC

“The most impressive holistic legacy of the 20th century...”

www. asnyc .org centerpoint gallery

IN THIS SECTION:

Research at its most familiar modern level, in a laboratory, performing repeatable tests—that is what the Lili Kolisko Institute is bringing to the service of the medications used by anthroposophic and complementary doctors.

Free Columbia is multiple initiatives: art school, social funding, community involvement.

EurythmyOnline.com is a terrible mistake, or terribly brave—a breakdown or a breakthrough?

T.H. Meyer is bringing his intelligent European passion for anthroposophy into a new English-language publication.

Christopher Schaefer remembers three persons of initiative from the world of business and funding.

Validating Medical Remedies: Renewing the Research

by John Beck

A four-year-old non-profit research institute in Wisconsin is working to validate and extend the knowledge on which anthroposophic and homeopathic health products are based. It is a natural outgrowth of the life commitments of three physicians who put Rudolf Steiner’s therapeutic insights at the heart of their practices, then sought to develop and produce new and improved remedies and supplements, and now are rallying support for the research he hoped to see almost a century ago. The production company, True Botanica, is well-known in the field, and the research institute was initially named for it. To make clear that its work is distinct from and aims beyond the company’s needs, and to honor an early and deeply committed researcher, the foundation has become the Lili Kolisko Institute.

Background

Rudolf Steiner’s wrote his last book with Dr. Ita Wegman: Fundamentals of Therapy: An Extension of the Art of Healing through Spiritual Knowledge, as its first English translation in 1925 was titled. Anthroposophic Medicine (AM) is now practiced worldwide. As the word “extension” suggests, AM is “complementary” not “alternative” to standard Western medicine; the resulting practice is “holistic” or “integral.” Rudolf Steiner expected participants in his medical courses to be MDs or students pursuing the standard degree. On that foundation he added new insights from his research which materialistic approaches could not reach. These were grounded in a full picture of the human constitution: a physical body, an body of life and formative forces (etheric body), the astral body of feelings and lower consciousness, and the ego. Body, soul, and spirit are expressly considered in the nature of the human being.

AM also works from a “wellness” model, recognizing the health-giving activity of the body of formative forces as fundamental. In an “illness” model attention is drawn more to symptoms than to the whole being and “patients” often become a passive battlefield where doctors combat illness. In Steiner’s research health and illness appear as one dimension of an individual’s karmic path and life experience, and the individual self or ego can be powerfully involved in healing.

Medicine makes extensive use of healing substances. Many pharmaceutical companies are major corporations and major players in medical research and education. Steiner recognized and pointed out numerous therapeutic uses of plants, metals, and mineral substances, and considered homeopathy, the use of highly diluted and “potentized” preparations, a valid approach. The Weleda company was organized in Steiner’s lifetime to provide anthroposophic preparations.

In his last months of activity Rudolf Steiner observed that with adequate funds a breakthrough could be made in anthroposophical scientific research. Funds have never approached the level he hoped for, however, so in medicine and other fields the advances that are possible are often carried by the efforts of a few individual doctors, therapists, and independent researchers.

Lili Kolisko (from the Institute website)

Lili Kolisko (September 1, 1889–November 20, 1976) was one of Rudolf Steiner’s most significant students. Her first meeting with anthroposophy occurred in 1914. She was working at the time as a volunteer helper in a hospital where she met her later husband Eugen Kolisko. (During

12 • being human

initiative!

this time she learned practical laboratory methods, essential skills for her later research activities.)

At one point Eugen Kolisko asked her: “May I give you a book?” and when she agreed he gave her Rudolf Steiner’s Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and its Attainment. It made a powerful and immediate impression on her. Apparently she read this through in one night and in the next several months read every single book of Rudolf Steiner’s that Eugen Kolisko had in his possession.

She met Rudolf Steiner in 1915. When she was introduced to him he told her, “Oh yes, we know each other already.” In her own independent and forward manner she decisively answered, “No,” and insisted on this “No” even as Rudolf Steiner persisted in affirming that they already knew each other, until he helpfully added, “Nevertheless, nevertheless, from before.”

In her first longer conversation with Rudolf Steiner, in May 1915, she reminded him that she had written him a letter and would have liked an answer. She had probably mentioned in that letter details about her very difficult youth and asked for advice related to her sleep. He answered her that that she should envision an abyss into which she would let rose petals float to the ground and then gather them again. He added that she had had a question in the letter about occult chemistry and advised her first to fill some gaps that she had in that area and only then tackle the specific problem. Then suddenly he said to her “You are seeing the ether.”

As a researcher, Lili Kolisko’s first contribution consisted in following up an indication of Steiner’s about the activity of the spleen. Rudolf Steiner had made the comment in lectures given in 1920 (Spiritual Science and Medicine) that one of the occult roles of the spleen is to regulate the intake of nutrition and its distribution to the various organs. He explained that the spleen has the function to give us the ability to eat at times of our choosing and yet enable the body to receive its nutrition on a regular basis, and felt that one could demonstrate physiologically this function in the laboratory.

Lili Kolisko studied the platelets that were generated by the spleen in subjects who had been eating regularly

versus people that had meals at irregular times. She discovered that under the appropriate circumstances a new type of speckled platelets would be seen under the microscope which she and Rudolf Steiner later called “regulator cells.” Steiner mentioned this work often and made the statement several times that if this type of research had occurred at a normal university it would have received international acclaim.

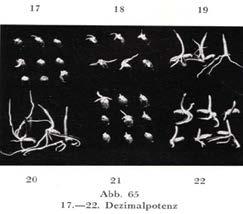

Her second major contribution was to develop a socalled germination test to show the influence of potentized substances on living organisms. This work grew out of a question that she posed to Rudolf Steiner essentially asking how one could determine which potency of a specific substance would be most beneficial to be used in a hoof and mouth epidemic that was occurring. Steiner advised her to grow wheat seeds and sequentially water them with various potencies of the substance in question. The resulting growth curves would give the desired answer. Lili Kolisko continued this work throughout her lifetime generating literally thousands of these curves and contributing greatly to our understanding of the work with potentized substances. It must have been a lifelong disappointment for her that the envisioned cooperation between her and medical doctors never came to fruition. It is in particular this aspect of the work that the Institute which carries her name is attempting to continue and further develop.

Rudolf Steiner valued Lili Kolisko also as an esoteric student. She was one of a handful of people that he personally allowed to read and hold the First Class lessons.

Lili Kolisko’s life continued to be both tragic and difficult. Due to extreme disagreements between the Koliskos and certain influential members of the Anthroposophic Society, she and her husband Eugen, then a much respected anthroposophic doctor and school physician to the Stuttgart Waldorf School, left Germany in the 1930s and resettled in England. Eugen died soon thereafter of a heart attack. Lili lived in extreme poverty. At one point apparently she was earning a living by sewing purses. Nevertheless during this whole time she continued her germination potency work as well as very significant research experiments on anthroposophic paper chromatog-

spring issue 2015 • 13

Lili Kolisko

raphy. In these last mentioned experiments she repeatedly showed that one could demonstrate the effect of star constellations on metals and other substances.

The anthroposophic physician Gisbert Husemann pointed out that Lili Kolisko’s work begins at the same time—in 1920—when Rudolf Steiner lectured on Thomas Aquinas. Steiner pointed out later on that in those lectures he had intended to demonstrate the new path that natural science needs to take into the future. In the thirteenth century Thomas Aquinas was still concerned with a material world on earth and a spiritual world “in the heavens.” Today, Steiner emphasized, this duality has to be bridged and the work of the spiritual world intimately affecting physical phenomena has to be recognized. It is perhaps not just a coincidence that the researcher Lili Kolisko was quietly beginning to fulfill precisely the challenge that Rudolf Steiner had postulated, bringing awareness for physical phenomena that are clearly caused by spiritual events. Husemann quotes Steiner (10.22.1922; CW 218) that in regard to Lili Kolisko’s work “we are working not just in the presence of an exclusion from the public consciousness but also in the presence of an exclusion of the interest from the Anthroposophical Society.”

One gets a heightened appreciation for Lili Kolisko’s work when one keeps in mind that Rudolf Steiner asked her to give a full lecture about her research during the Christmas Foundation meeting. On the same day he gave as the “rhythm of the day” the verse:

This the Elemental Spirits hear In the East, West, North, and South May Human Beings hear it.

Rudolf Steiner had intended to direct a renewed appeal to the members of the Anthroposophic Society for financial support of the Kolisko research. With his death in 1925 this appeal never materialized.

The physicians

Drs. Ross Rentea and Andrea Rentea write: “Our family practice clinic in Chicago (Paulina Medical Clinic [www.paulinamedicalclinic.com]), emphasizing integrative, holistic, homeopathic and natural medicine, opened in 1983. Now more than 30 years later we look back with satisfaction on having helped thousands of patients with their health needs. Throughout we have used the gentlest, most holistic and natural medicine approaches that were possible for the treatment of both acute and chronic illnesses, for both adults and children. Our goal is main-

taining or recovering your optimal physical health so that you can continue a fulfilled moral and spiritual life that helps others around you.

Dr. Andrea Rentea graduated from the prestigious Chicago Medical School (now the Rosalind Franklin University), in 1975, and after her residency in Chicago she spent four years at various European clinics studying anthroposophic/complementary medicine. She specializes in women’s concerns and children’s problems, both physical and emotional. Outside her practice her additional activities include consulting to various Waldorf Schools on the medical needs and handling of difficult children.

Dr. Ross Rentea graduated from the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine and after his residency in NYC he also spent four years at various European clinics studying anthroposophic/complementary medicine. He has published numerous articles in peer reviewed medical journals (such as basic science studies on the effect of mistletoe extracts on the successful therapy of cancer) and holds a patent for a medical device.

Dr. Mark Kamsler provides pediatric medical care to all ages of children/young adults and also provides consultative care for adult patients looking for a more holistic input. He received his MD from the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor and completed a residency in Pediatrics at CS Mott Children’s Hospital there. He has had a general practice in the Milwaukee area since 1995. He has worked extensively as a consulting pediatrician to several Waldorf Schools and has spoken to groups ranging from Birthing Centers and La Leche League to Grand Rounds at several hospitals.

Alongside their practices all three physicians are very active in public education, in lectures, conferences, and webinars. But their commitment has not ended there.

14 • being human initiative!

From left: Mark Kamsler, MD, Ross Rentea, MD, Andrea Rentea, MD

True Botanica1

“Following a long standing interest in researching ways for creating new quality natural remedies, appropriate to the spiritual and physical needs of the contemporary individuals, three physicians founded True Botanica in 2004: Dr. Mark Kamsler, Dr. Andrea Rentea and Dr. Ross Rentea. The GMP (Good Manufacturing Practices) compliant main facility is located in Hartland, Wisconsin,” west of Milwaukee and about two hours from Chicago. The company goal is “to create the most safe and effective full spectrum products possible that work harmoniously on body, mind and spirit. The formulas are designed by uniting the best that nature has to offer with the latest emerging modern nutritional technology.” The company is now offering “‘validated’ homeopathic/ anthroposophic remedies—a worldwide first.”

“Essential processes that constitute the core of our products are done by hand, in a quiet environment conducive to an inner sense of responsibility, reverence and gratitude to the natural substances used in the making of the healing products. All products are made in the morning, under conditions when we can be reasonably assured that only a positive energy will accompany the production process. (For example no manufacturing takes place during storms, etc.) The ingredients for our formulas are carefully sourced from non GMO, biodynamic and organic materials. The formulas are designed by keeping in mind the best of insights given by the scientist Rudolf Steiner and the latest in modern nutritional technology. Some features we are particularly proud of are:

A threefold design to our products that makes them particularly effective on all three levels of body, mind and spirit.

A proprietary method for a more efficient extraction of herbal materials, resulting in a non-alcoholic tincture.

Creating full spectrum formulas where the natural salts and minerals of the medicinal herbs are included.

New blends of entirely natural fragrances, valuable for the cosmetic line and aromatherapy, such as a blend of rhododendron and other steam distilled essential oils. These are currently used in our face moisturizer, cleanser cream, bath oils, salt body scrubs and health creams.

1 Quotations from www.truebotanica.com

Rhythmically preparing substances in order to achieve new qualities in the substances. Additionally, a final mixing is accomplished with the Swiss bioengineering Inversina™ mixer.”

The Lili Kolisko Institute2

Work with the True Botanica company led to the three physicians also co-founding the Lili Kolisko Institute which conducts education, research and social activities in the anthroposophic health care field. A laboratory is being built to conduct continuing research into the demonstration of the validity of anthroposophic/homeopathic remedies. The doctors wrote friends and donors last fall:

As we all would agree, introducing others to Rudolf Steiner’s work is a quintessential first step, and continuing to “spread the word” is of course crucial, but eventually the newcomers ask: “And what have you done with all the material you are so excited about?” Then comes the tough part, showing for example applications in clinical practice... and those in turn are based on previously done research and insights thus gained. Among many activities perhaps nothing is more financially demanding, and dependent on altruistic trust, than laboratory work. But the future benefits are enormous. The question everybody could ask themselves is: How many cents a day am I willing to sacrifice for the support of ongoing research? We believe that this work touches all of us, irrespective of our specific situation. This year we celebrate four years of research at the Lili Kolisko Institute. But the economy and materialistic feelings of our time are such that our financial situation is not rosy. We have had to let co-workers go. We have had to cut down on the number of projects, etc. Still, we trust in the future support of our community.

The Lili Kolisko Institute is the former True Botanica Foundation. The nonprofit 501(c)3 organization was renamed to more clearly show its independence from the True Botanica company. Its research results are available to all interested parties, and donations made to the Institute are tax deductible.

The True Botanica company whole heartedly continues to support the Institute, but it cannot cover all the costs by itself. To keep the research work and educational programs going we are dependent, more than ever, on donations from the enlightened community who understands and values this medical-biological work.

spring issue 2015 • 15

2 Quotes from www.koliskoinstitute.org and from emails to friends and clients.

The research results are not theoretical. The results of this work have already been quite tangible. Over 180 new remedies have resulted to date from these experiments. Hundreds of people, lay and professional, have been introduced to the ideas and benefits of anthroposophic medicine. For the future, among others, we hope that with your help more data will be forthcoming showing the importance and reality of spiritual rhythms and forces.

Examples of the research

The Kolisko Institute website highlights the following areas of current research:

Boswellia (frankincense) experiments; bioavailability of two commercially available brands compared.

Chromatography experiments: Boswellia, Lightroot™ (the yam Dioscorea batatas), Hyssop. “Chromatography, such as in the method demonstrated here, is a means by which one can begin to visualize the life forces (the etheric forces) that underlie either natural substances like plant extracts, minerals, etc., or that can (or should be) found in finished products.”

Germination experiments. “Experimental behavior of more than 100 substances to date have been analyzed by the germination method in order to find out which potencies are the more active for each specific substance.”

The Kolisko Validation™ Method: improving quality control of homeopathically potentized OTC drugs.

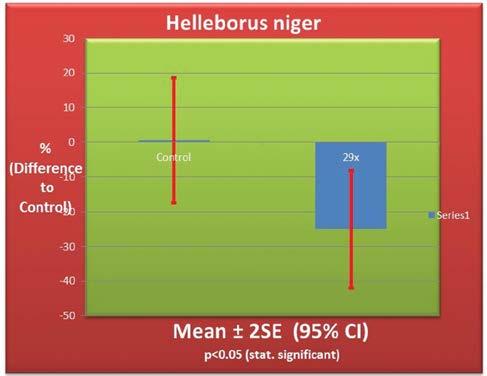

A substantial paper by Ross Rentea MD and Mark Kamsler MD discusses this last area, “a standardized biological test which allows validation, i.e. verification of effective activity, of homeopathically potentized substances. ... From a certain point forward this stepwise process of dilution and agitation [potentization] results in a product that has purportedly no molecules of the original substance left—and yet it is supposed to have a therapeutic effect. It is this characteristic that causes the scientific community to call homeopathic remedies ‘implausible’ and doubt their effectiveness.

“To our knowledge this is the first time that such an objective, statistically analyzable ‘potency validation’ test is included in the quality control process of manufacturing of homeopathic/anthroposophic products. This could constitute an additional step in assuring the consumer that the product containing an ultra-high dilution is not ‘just water or just sugar pills.’ Additionally, the test allows a more objective interpretation of the potencies of

each substance … [and] it is hoped that ultimately the resulting potency-validated homeopathic/anthroposophic medications will emerge as clinically more effective.”

So, how can it be established that an effect is present in the result? And how can the commonly used potencies be evaluated to show whether they are in fact the most suitable? “The answer was given by Rudolf Steiner already in the 1920s. In a reply to a question from his student Lily Kolisko about a method for finding the most appropriate potency of a substance that was to be given as a remedy against hoof and mouth disease in cows he suggested to her: Let wheat seeds germinate under the influence of a series of potencies of that substance. The response of the seeds to the various potencies will result in an overall curve showing the ‘vitalizing process,’ or lack of it, created by specific potencies on the seedlings. This, he added, would not only be valid for the plant but also for the animal organism. He further characterized the resulting curves in a lecture (3.31.1920):

“‘(In the series of potencies …) you will reach a Null point. Beyond that the opposite effects (of the test substance in the first zone) appear. But this is not all; the further path leads to another Null point for these opposite effects. Passing the second Null, you will come to a higher form of efficiency, tending in the same direction as the first sequence but of quite a different nature. It would be valuable and appropriate to plot out the different effects of potencies in curves of this special manner.’

“According to Steiner the curve for the first two zones can be seen on the paper but an accurate representation of the third zone would need to show the curve coming out of the plane of the paper at ninety degrees.

“Based on these insights Kolisko proceeded to do the work that led to germination curves of potencies. She pursued this project essentially lifelong! She let wheat seeds germinate for a number of days in separate containers wa-

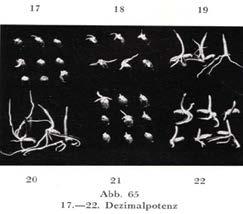

tering them with either water as control or with increasing potencies of a particular substance. (In general 1x to 60x; many experiments however to 600x!) Above are samples of findings from one of her early experiments. (Here,

16 • being human initiative!

potencies D17 and D18: no response; D19 and D20: big response; D21 again low, and so on.)

“The value of Lili Kolisko’s work consists in demonstrating for the first time that sequential potencies increase and decrease in effectiveness in a rhythmical, semisinusoidal manner. When at a later time several of her germination potency curves were looked at cumulatively, the semi sinusoidal pattern emerged even more clearly. Kolisko herself believed that every substance has its own completely characteristic ‘signature’ curve and that it would be of extreme importance for every doctor to know the curve of every remedy as naturally as they would know the appearance and signature of every plant and mineral. To increase accuracy she would have welcomed, she said, a cumulating of several experiments of the same substance with the same potencies.

“Today the plant germination technique is generally accepted among credible researchers (Baumgartner et al.; Bellavite et al.; Betti L et al.; Bonamin; Fisher; Husemann, 1992; Scherr et al.) as a solidly recognized model for the study of potentizing processes. However, to the present, as far as we know, none of the in vitro plant models—or similar—have been used in the sense desired by Kolisko, and pursued by us, as a practical tool for quality control in the manufacturing process of ultra-high diluted (potentized) medicines. … We have developed a new relatively simple (albeit very labor intensive) protocol for a germination based model that we use to accomplish the stated purpose of demonstrating that the final potency going into a final OTC homeopathic/anthroposophic remedy is indeed active and can influence a biological system. To overcome the above stated weakness in the Kolisko experiments our method uses a statistical validation. …” In brief, the various potencies are tested against control samples. The variation from the control is evaluated statistically to obtain a degree of confidence that the preparation has an effect that goes significantly beyond the “mere” water control.

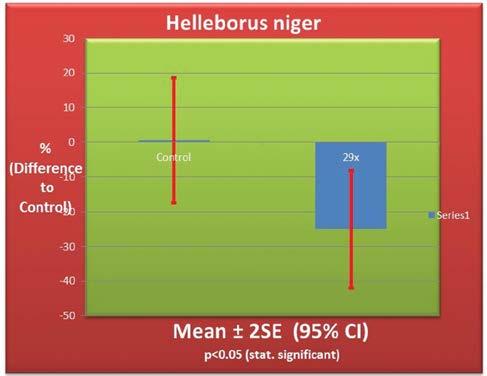

“The Helleborus graph (above, the control on the left, the 29th potency on the right) clearly demonstrates the significance of this anthroposophic research. Helleborus is a toxic plant that Rudolf Steiner indicated, for the first time, would be beneficial in inhibiting tumor growth. The final potentized product thus should show an inhibiting influence on the growth of the wheat seeds. (We have ample evidence to show that other substances have a stimulating influence on the growth of the seeds.) Indeed, we were able to show that the 29th potency has such an inhibiting effect. We call this ‘proving’ of the effectiveness of the specific potency a ‘Kolisko Validation.’

“Beyond the obvious importance of going a long way toward increasing confidence in the product itself this method is an indisputable contribution of anthroposophic medicine/research to a ‘real world’ medical quandary.”

At www.koliskoinstitute.org a full paper describing the above processes in detail is linked under “Research.”

Conclusion

Three dedicated physicians found anthroposophic methods effective in their work with patients. Together with a team of dedicated co-workers they went on to create new and assured-quality medications, and now to resume and expand a line of testing and validation originated by Rudolf Steiner and carried selflessly for decades by Lili Kolisko, all while engaging in efforts to educate the public on anthroposophic medicine. They see their efforts in the direction of Steiner’s wish that anthroposophy would make original, true contributions to solving the world’s needs. The question remains, will this core work find friends near and far with the will to sustain it.

John Beck is editor of being human and communications director for the Anthroposophical Society in America.

spring issue 2015 • 17

A stage in the ‘Kolisko Validation’ testing.

Free Columbia: Spiritual Activism, or What Does Our World Need Now?

by Laura Summer

by Laura Summer

…Art is the ‘only’ possibility for evolution, the only possibility to change the situation in the world. But then you have to enlarge the idea of art to include the whole of creativity. —

Joseph Beuys

The date was September 14, 2009. Thirty-five people sat in a circle in Bright Wing Studio in Hillsdale, New York. Names traveled around the circle, the history of painting in that studio was described, memories and hopes for the future were voiced, the feeling of “dropping in” from a nine-foot skateboard ramp was mentioned. And Free Columbia began.

But what does free mean?

Free Columbia is an intensive exploration into art, Goethean observation, anthroposophy, and social change. When we talked about starting Free Columbia we realized that it would have to be available to everyone no matter their financial situation. It would have to be supported and free. But what does free mean? To create something free meant to create a vessel into which inspiration was free to flow, for teachers, for students. It meant expanding a form to include the unexpected, the challenging, even the unadvisable. Many people said not to do it. And not to call it free. That people would not support it, that they would take it for granted. And sometimes that is true; but mostly not. People have rallied around the principle of accessibility. The community holds us up. At the moment we have forty people making monthly pledges. We have

run for six years now and although we do sometimes run out of money it always flows back in quickly enough. We provide all of our programming without set tuitions or materials fees; we encourage everyone to donate.

From a little painting program...

In six years Free Columbia has grown from a little painting program in the studio behind my house to an initiative including many people working in a variety of ways. Here are a few snapshots from over the years:

In our third year eleven full-time students finished the program of painting, drawing, and puppetry with an exhibit of the year’s work held at a space next to the Family Dollar store in Philmont, New York. This exhibit in the middle of the town was reflective of our year which saw us moving out into the world around us. Our summer conference, concerned with artistic experience and the future of art, was held at the Basilica Industria in Hudson, NY and was attended by 45 people from many countries including Finland, Israel, Italy, and France.

In 2013/14 (our fifth year), eight people participated full-time, 120 people in part-time intensives locally and in California, Oregon, and Washington, DC. Over 1000 people saw the 2014 puppet show, The Legend of the Peacemaker. In Free Columbia’s four “Art Dispersals” 295 works of art have

Inside

outside

(above) and

(right) the Free Columbia Space at 84 Main St, Philmont NY

18 • being human

Students doing an exercise in color after-image

initiative!

The movement in the soul

What is art? What is freedom? According to Rudolf Seiner art is the movement in the soul created by the sculpture, painting, music, etc., that the person is observing. How do we move souls to become more alive, more balanced, more productive of a future that values truth, goodness, and beauty? At Free Columbia we teach our students to locate soul movement: the quality realm. How does blue make you feel, how is it different from red? We learn to quiet our sympathies and antipathies and to ask what is here, what language does it speak, can I enter into the conversation if I learn the language? This is a way of developing perception of non-material reality. It is a way to make anthroposophy practicable.

Between darkness and light, between one color and another, between one tone and the next, there is movement. In a conversation with Jesuit priest Friedhelm Mennekes, Joseph Beuys said, “Christ is in the movement.” Can we experience this? We can perceive here if we quiet our inner chatter and observe. In art we are working in a way often different from everyday concerns. We are learning to observe reality, see what is needed, and then to act.

What is freedom? What is responsibility? And then to act

Next year we will offer a six-month full-time course on perception through color in relation to social change, a low-residency intensive on painting, a module on social threefolding, and perhaps a program in sculpture, as well as ongoing practical arts classes, performances, children’s classes and camps, classes for developmentally disabled adults, classes in the prison, summer and winter intensives, study groups and conferences. Next summer’s two-week intensive will be on Rudolf Steiner’s sketches for painters. All accessible to everyone. All supported by gifting. All in all, a very engaging way to work with spiritual science.

In the spring we will also take our financial model to a new level. We will run a campaign to pay forward one-

third of our operating expenses. With one-third coming in in monthly pledges and one-third expected from donations throughout the year, a successful campaign will make it possible for Free Columbia to work without a monthly worry of running out of money.

“Work cures everything.” — Henri Matisse

If you are interested in our work, would like to participate in any way, or would like to help us move forward, please visit www.FreeColumbia.org. And see the Gallery (pages 33-36) in this issue for work from Free Columbia.

Laura Summer (laurasummer@fairpoint.net) is co-founder with Nathaniel Williams of Free Columbia. Her approach to color is influenced by Beppe Assenza, Rudolf Steiner, and by Goethe’s color theory. She has been working with questions of color and contemporary art for 25 years. Her work, to be found in private collections in the US and Europe, has been exhibited at the National Museum of Catholic Art and History in New York City and at the Sekem Community in Egypt. She founded two temporary alternative exhibition spaces in Hudson NY, 345 Collaborative Gallery and Raising Matter-this is not a gallery

Free Columbia mural in Philmont, NY, 2014

spring issue 2015 • 19

Free Columbia Painting Studio 2015

been dispersed. Donations to support free culture were accepted from the recipients.

Free Columbia mural in Harlemville, NY, 2014

Can Eurythmy Live Online?

by John Beck & Cynthia Hoven

by John Beck & Cynthia Hoven

For over a year, I have been working on breaking through the digital barrier to create an online eurythmy experience. After long and hard and creative work, I finally launched the website yesterday, Michaelmas 2014. I would be delighted if you would take a look: EurythmyOnline.com. There are over 50 video recordings teaching people basic warm-up exercises, rod exercises, spatial movements, vowels, consonants and also a few soul exercises. Take some time to look at the site, check it out, get the “flavor” of what I am doing by reading the texts, trying some of the freebies, downloading the pdfs.

—Cynthia Hoven

Times change—whatever that actually means—and we find ourselves in situations that demand choices, made on our own responsibility. When Ita Wegman, MD, proposed to move her medical practice from Zurich and open a clinic in Arlesheim, Switzerland, near the Goetheanum, she of course asked her teacher and advisor Rudolf Steiner to approve or disapprove the plan. Which he declined to do. When she went ahead and months later was ready to show him the facility, it’s reported that he promptly started to help write the promotional brochure.

Eurythmy

Rudolf Steiner created eurythmy, or discovered it, or revealed it, or all of those and more. It seems to stretch deep into the grounds of existence as well as playing a part still hard even to imagine in humanity’s future evolution. Eurythmy is a performance art, a healing art, a teaching art. Perhaps it is the flowing substance of life itself finding its newest expression, by invitation, through the wakeful and devoted human being?

So it is entirely natural that eurythmists have worked very hard to engage and manifest all that Steiner and Marie Steiner-von Sievers established of eurythmy in their lifetimes, and draw a line there. There is, after all, real opposition to a human evolution into freedom and love.

Spiritual Realities

Rudolf Steiner made very clear that humanity today is locked in a struggle to become aware of great cultural-civilizational-evolutionary forces. He identified these with real “spiritual beings,” conscious and intentional entities working at a higher stage of development than present-day humans. Some of them strengthen us in the long run by trying to draw us onto their own paths.

Our current strongest opponent, reported Dr. Steiner, is a being for whom Steiner used the old Persian name “Ahriman.” Ahriman’s gifts and capacities help us release great physical powers and create material abundance. He helps us become hard-headed and objective. It also seems that his inclination is to remake the world on a mechanical basis; that is the kind of perfection that is within his powerful but one-sided understanding. Life in nature and free individuality in the human being do not fit within his understanding of cosmic purpose. If we do not recognize the force of his identity and intentions, then we will believe that it is we ourselves who want to merge human beings with machines, eliminate our messy free choice, and pursue an endless, painless, deathless physical life.

So would we subjugate this still-new art of eurythmy to Ahriman?

Freedom and initiative

But then there is the equally large question of human beings’ taking responsibility for their actions and choices. And times changing, whatever that means. YouTube and online videos are the first point of reference for younger generations, and trained eurythmists willing and able to teach are few and far between (and must struggle to make a living). What do you do then—or rather, now? Do you

20 • being human initiative!

Creating and evaluating EurythmyOnline.com –a personal eurythmy site

protect and defend, or step out and take risks?

Cynthia Hoven directed the eurythmy training program at Rudolf Steiner College, near Sacramento, California. When the program had to be closed for financial reasons, she was faced with personal needs as well as professional choices. She wrote a remarkable book on eurythmy. She worked with young people on new social visions. And she came finally to the conclusion that she might be the right person to create an online eurythmy learning resource. Service to eurythmy and to other human beings, and the challenges of her own professional and karmic path, are now fully intertwined. What follows is in Cynthia Hoven’s own words… —John Beck

A personal mission statement

I’d like you to see my personal mission statement. Just in case it sparks. I wrote it about 18 months ago, before I got started in earnest, to keep me focused. I like looking back on it, both in the times when I am getting paying customers and in the times when I’m instead getting dozens of non-paying customers—because just knowing that they’re doing eurythmy makes me sing.

Eurythmy Online Mission Statement

Eurythmy is an art form that is inspired by, integrates, and makes manifest our divine nature in body, soul, and spirit. Eurythmy is a path of embodied spirituality.

This program is a bold undertaking to present an online eurythmy curriculum through e-courses, CDs, and video recordings, with uncompromising integrity, overcoming the limitations of technological media.

The primary purpose of this work is to make eurythmy and also the studies of anthroposophy and the arts that spring from it available to thousands of people, in service of humanity and the planet earth.

The secondary purpose is to create a vibrant and thriving business for me, selling lessons, and also teaching live eurythmy classes and other courses.

The third purpose is to create career opportunities for others to lecture and teach in this program.

Cautions and concerns

For many many years I was as conservative as anyone else could be about the thought of filming eurythmy. I knew that Rudolf Steiner disapproved of movies. I know that in films you can only see the image of things—in two dimension—and not the thing itself. I consider that in watching films we tend to become inwardly passive and merely receive the images as they are presented to us. I know that in film we have only the illusion of having a real person talking to us: we don’t have the other person really with us, with blood and breath and body. I know that these are all true because the medium cannot carry the true element of the living etheric.

In time, however, I began to wrestle with other questions. Would it be possible to help eurythmy become more well-known by crafting a beautiful website? How could I help eurythmy become more of a cultural reality, and not something that belongs only to the trained eurythmists? Every person can sing or speak or play a bit of an instrument or paint: why shouldn’t everyone have some access to eurythmy? Is it possible to bring eurythmy to people who live in remote places and will never meet a eurythmist? What about people who do a bit of eurythmy at a workshop and want to do more, but can’t quite remember how?

As I entertained these questions, I realized how much I want to participate in creating a new openness around eurythmy—as in fact I had begun by writing my book about eurythmy.1 I know it is a modern path of movement meditation (with great initiatory teachings for those who go deeply into it), and that I want to be part of making sure that it lives and doesn’t just wither away because it is not known or because it is held too tightly by some who claim to “possess” it. Why shouldn’t a group of people do Halleluiah at a faculty meeting? Why shouldn’t friends do a bit of eurythmy themselves? Hopefully they will do some and then go on to look for a eurythmist who can teach them properly. In saying this, I don’t want to detract from the value of a eurythmy training! Trained eurythmists should be like graduates of Julliard, or blackbelt Tai Chi masters. But everyone can do a little bit!

So I resolved to start the website, but I recognized that I would have many obstacles to overcome. How could I present the lessons in such a way that the viewer would be able to overcome the limitations of the medium? Would it be possible for me to create narratives that

spring issue 2015 • 21

1 Eurythmy: Movements and Meditations; A Journey to the Heart of Language. With illustrations by Renée Parks.

would enable people to internalize a lesson so deeply that they could recreate and enliven it from within themselves later on? What an exciting thought! I knew that because I have taught so many thousands of people, I would be able to introduce all of the lessons—threefold walking, contraction expansion, rod exercises, all the vowels and consonants: all 55 lessons—in clear, clean, poetic, inspirational language.

And so I dared myself to take on the task. And I feel that I have done as good a job as possible in the work. What remains to be seen is how well people will be inspired to take it up. What is missing in the lessons is the spark and the joy of working with a class of people, the contagion of having a live teacher carry you. What the lessons offer is an opportunity and a challenge for people to become self-motivated in their personal practices. How many people have the inner endurance, the inner power to commit to work on themselves in this way? I feel that this is the greatest limitation on the website.

The website contains four free lessons and over fifty paid lessons. About twenty to seventy people a day visit the website, and they linger for an average of 3.5 minutes— meaning some stay quite a bit longer. I judge that quite a few people are doing the freebies and that makes me very happy. Some people have purchased the special sequences, and some have purchased the whole set of lessons, designed to be enough for one lesson a week for a year.

For the most part, the feedback is immensely positive from those who are using the lessons. People are so grateful that I have freed eurythmy up for them to access on their own. Some have cried when they thanked me: they have loved eurythmy so much, but haven’t been able to continue on their own and longed for something like this. A few anthroposophic doctors have thanked me profusely for the work! Some eurythmists have expressed reservations, but others have thanked me and watch the lessons themselves before teaching their own classes because they find my style inspiring.

I was especially moved by a woman who works with women in trauma in Lebanon. She said she would never be able to find a eurythmist there, but she can use some of my offerings to help people become centered and feel peace. Here is another item of feedback:

We are a group of three women in Perth, Australia. Tomorrow morning we will embark together on your module for the Consonants. I have worked with your Freebies each day for a few weeks and find the gentle, methodical guidance very helpful. From there, creative

ways to deepen the practice are able to spring forth. It is so different from a class where several different elements are covered at one time. I feel this gently unfolding method will entrain a model of simplicity which will lay a strong foundation in each of us as individuals, and carry over into our shared movement.

Eurythmy Online—What does it mean?

It seems like only yesterday that I thought it would be madness to ever consider creating an online eurythmy website. Why? Eurythmy is all about living, moving presence. And that simply isn’t communicable through the computer. For all their bells and whistles, their fabulous color effects and images, and their capacity to transmit gazillion-bytes of information faster than the speed of thought, computers only give the appearance of reality. Computers live on the surface of things: they perpetuate the world of maya 2 They cannot give us the true experience of being in the warm presence of another person.

Eurythmy, on the other hand, opens the door for each of us to celebrate communion with our own spiritselves, and with the world-spirit that has created all. And every instance of eurythmy must be permeated with presence: with your presence, with spirit presence.

When I teach live classes, one of my most important responsibilities is that I am fully present throughout the lesson to witness the best and highest in each one of my students. In honoring the fact that each person is a child of God, an active spirit presence awakening to their infinite spirit potential, I am inwardly attentive, patient, supportive, and generous. And through this act of witnessing, I see that everyone is beautiful when they do eurythmy.

And so: when I decided to create EurythmyOnline. com, I had some tough questions to face.

Would it be possible to create recordings that were so carefully crafted that I and my students would be able to overcome the electronic media? Searching for a solution, I carefully instruct people to watch the videos only as long

2 In ancient Hindu-Vedic tradition, the experience (later a teaching) that the sense-perceptible world is illusory, only the manifestation of the work of spiritual beings. —Editor

22 • being human initiative!

as they need to, to internalize the material I am teaching and then to turn off the recordings and work in silence. In that silence, I know that they can awaken to their own experience of spirit presence.

And then I had to decide: what sequence of instruction should I offer? Should I require that students all start at the very beginning exercises (weight and light, contraction-expansion, threefold walking) before proceeding to learn how to do the sounds of language? Or should I allow people to enter the curriculum at their own level, and choose for themselves where to begin? It took many month of design for me to come to my present solution, in which I encourage people to do the whole curriculum, but also break the content down into modules so people can take smaller chunks if they prefer.

And then came the question of money, for eurythmy is actually priceless. And, because it is my ardent wish that everyone should be able to do eurythmy, how could I charge anything for it? On the other hand, I have had real costs in building this website and in sustaining it. And through paying money for the lessons, students allow me to continue to live and teach and serve spirit in all the ways that life asks of me.

I know that I will be asked: Why did I do it? And I will answer: Because the “Spirit of Eurythmy” is longing to be relevant, to bring its refreshing liveliness to our age.

Why? Because I am aware of the millions of people in the world who will never have a chance to meet a eurythmist in person, but who may have heard of eurythmy, in real life or through their Waldorf connections or even in their dreams, and who want to learn about it and try it.

Why? Because I know that if we as eurythmists don’t find a way to step into the culture of electronic media, we will become increasingly invisible and, unfortunately, irrelevant. Blessings, —Cynthia Hoven

So here is a fresh new initiative, six months old, inviting your attention and response!

You can view the site at EurythmyOnline.com and you can contact Cynthia at choven@sbcglobal.net.

The Present Age

T.H. Meyer interviewed by John Beck

JB: You are known in America for important books on subjects from 9/11 to Rudolf Steiner’s core mission, and remarkable biographical works on Gen. von Moltke and D.N. Dunlop. You also give lectures over here, and have written about anthroposophy since Rudolf Steiner’s death and into the future. Can you speak of your own core mission—essential concerns you want to share with anthroposophists today?

THM: Well, if I dared to speak about my own core mission, I would say it consists in the humble attempt to elaborate biographies in harmony with Steiner’s core mission, which was, next to the social question, the revelation of concrete karmic relationships. In the two biographical works you mentioned this perspective underlay everything I did. This is also the case with the newly translated biography about Ludwig PolzerHoditz, which traces this pupil of Steiner’s back to the times of the Roman emperor Hadrian. And precisely in this respect I would like to share my concerns with fellow anthroposophists: that a karmic perspective on individuals is often left to fantasy, speculation, and the immature or premature expression of personal experiences in this field. Or it is totally overshadowed by an approach to Steiner’s research by philologizing and psychologizing, as is done by the new “critical” edition of his works undertaken by an individual deeply convinced of the “truths” of Mormonism.

Another concern is: Will more and more anthroposophists turn to the “core substance” of anthroposophy instead of merely hoping for an external growth of the movement? The lost harmony between inner deepening and going out into the world, between involution and evolution—a harmony that Nature establishes in the course of the seasons—should be restored within the anthroposophical movement. In the last decades there was too much one-sided going out on the one hand—trying to become everyone’s friend—and too much one-sided going inwards on the other hand—like clinging to the idea of the “esoteric” character of the Anthroposophical Society and the like.

spring issue 2015 • 23