anthroposophy.org personal and cultural renewal in the 21st century a quarterly publication of the Anthroposophical Society in America summer-fall issue 2017 Toward an Architecture of Social Transformation (p.14) A Call to Garden! (p.18) The Formation of MysTech! (p.20) Pathos and Spiritus (p.22) Being Human and the Life-Cycle of the Plant (p.25) Professor Fritz Carl August Koelln: “Each Day Anew” (p.37) Anthroposophy & Science (p.40)

being human

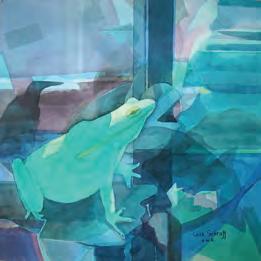

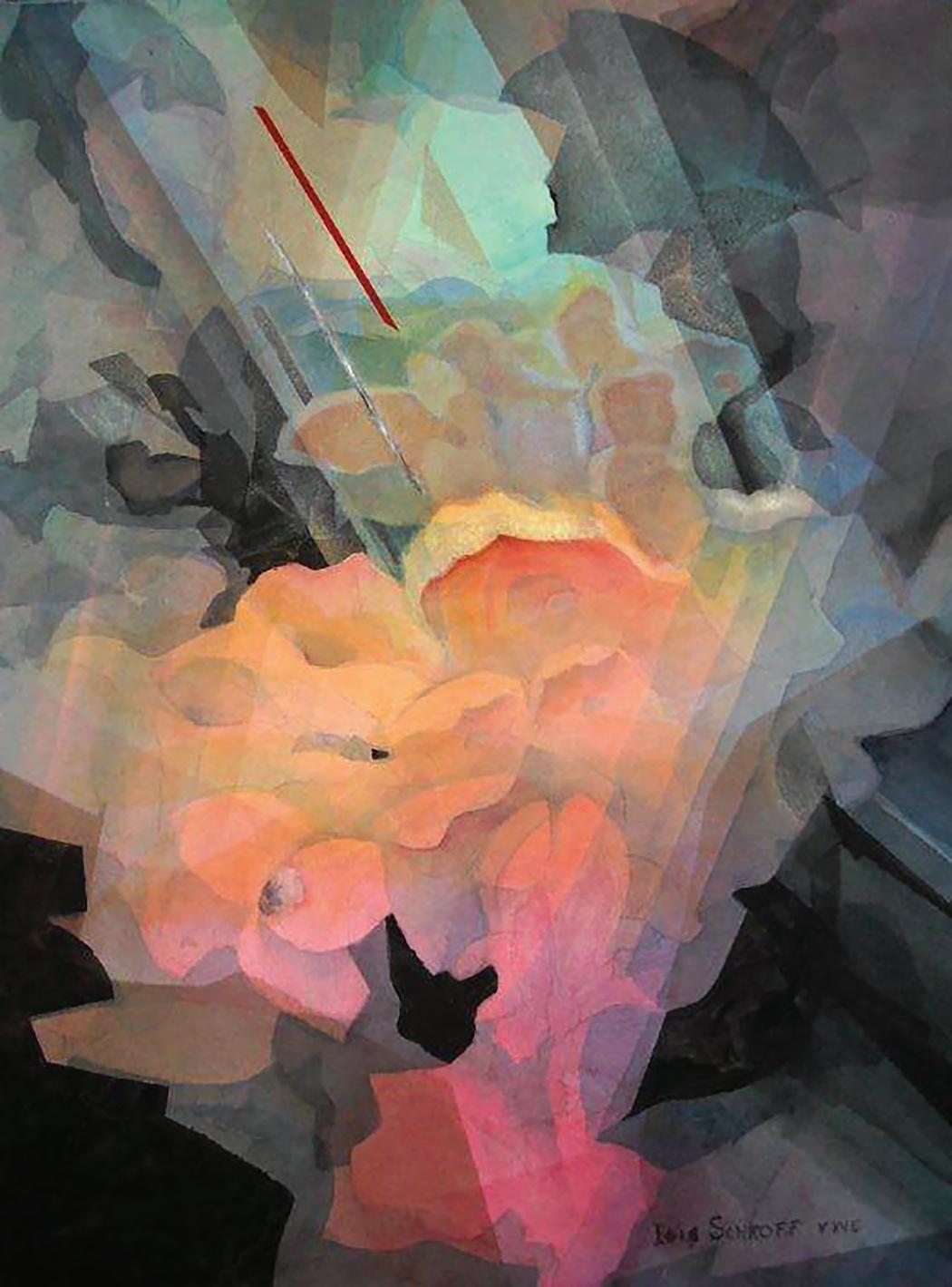

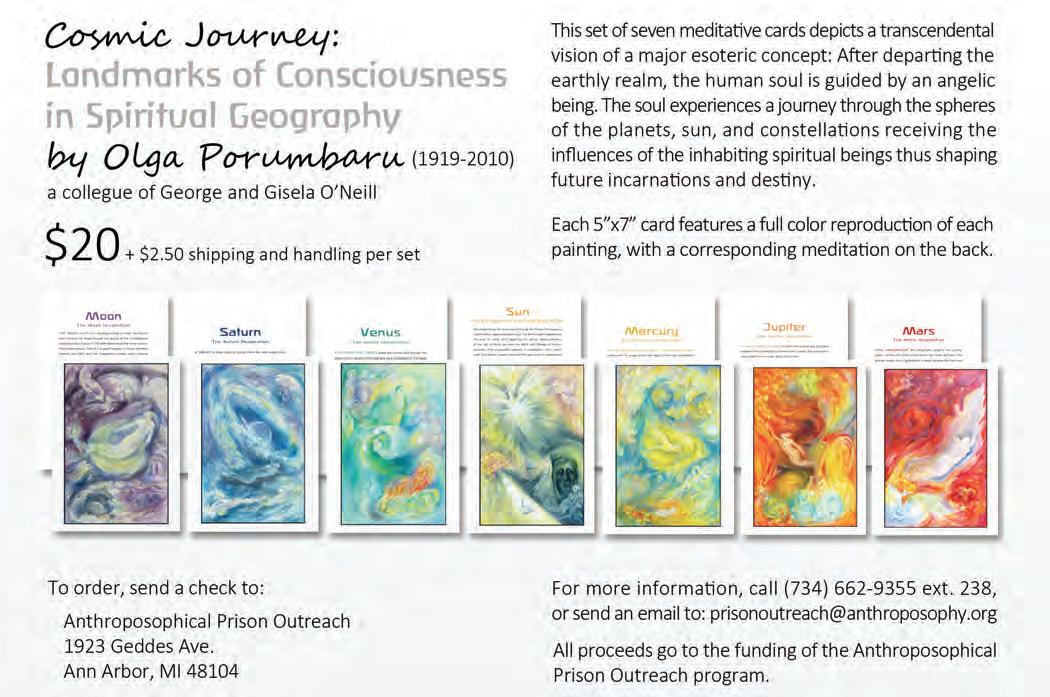

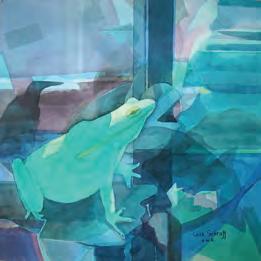

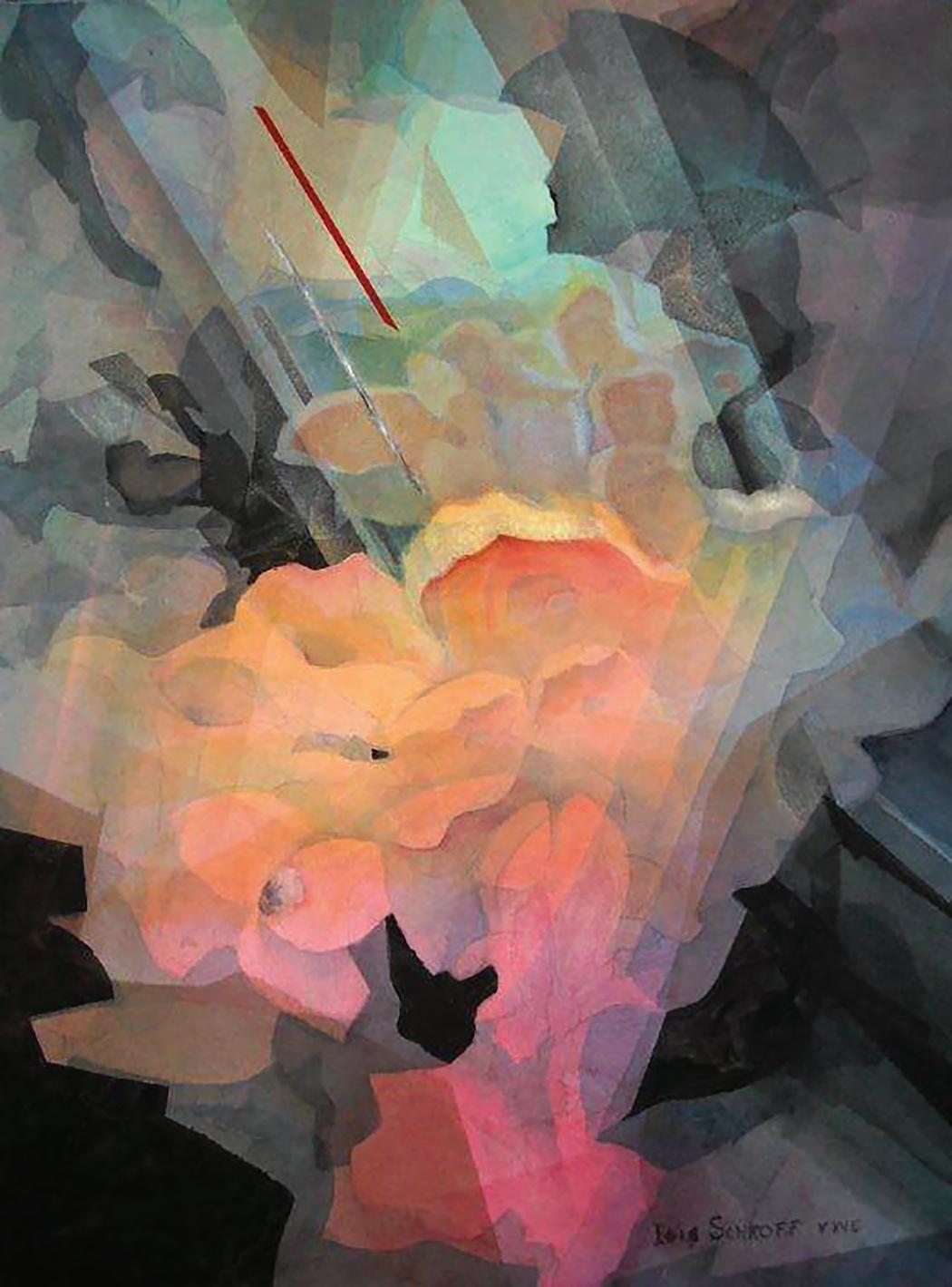

“Only a collection of DNA?” by Lois Schroff (see Gallery, page 31)

November 10-11, 2017

Programs and resources in visual arts eurythmy

music drama & poetry

Waldorf education spirituality

esoteric research economics

evolution of consciousness

health & therapies Biodynamic farming social action

self-development

WORKSHOPS

TALKS

STUDY GROUPS

CLASSES

FESTIVALS EVENTS

EXHIBITS

Regular Programs starting in September

MONTHLY LECTURES

by artist and educator David Taulbee Anderson

EVENING EURYTHMY WORKSHOP with Linda Larson

WATERCOLOR PAINTING WORKSHOPS

a new series with thirty-year Waldorf school and adult teacher Gosha Karpowicz

MONTHLY MEMBERS’ EVENINGS

“Light & Warmth for the Human Soul“

FESTIVAL CELEBRATIONS

Michaelmas, Advent Garden, The Holy Nights Plus special events & study groups...

MONTHLY GROUPS

Speakers Group and Reading for the Dead WEEKLY GROUPS

Meditation, Rudolf Steiner texts

(Toward Social Renewal, Occult Science, Theosophy )

Low-Residency

Elementary & Early Childhood Teacher Education Programs with MEd Option

• Specialized Subject Teacher Intensives

• Professional Development and Introductory Courses & Workshops

www.sunbridge.edu

Rudolf Steiner Bookstore

Open Tue-Thurs 1-5pm, Fri-Sat 12 noon-8pm, Sun 1pm-5pm; call for info: 212-242-8945

Steiner has “the most impressive holistic legacy of the 20th century...”

— NY Open Center co-founder Ralph White www. asnyc .org centerpoint gallery spiritual therapeutic world & outsider artists

The New York Branch

Anthroposophical Society in America 138 West 15th Street New York, NY – (212) 242-8945

Us As We Celebrate

Teacher

Join

50 Years of Inspiring Waldorf

Education

ANTHROPOSOPHY

2 • being human

NYC

INNER (SPIRITUAL) RESISTANCE

STEINERBOOKS , Great Barrington, Massachusetts USA & THE ITA WEGMAN INSTITUTE , Arlesheim, Switzerland

Invite you to our second CONFERENCE IN AUSCHWITZ, POLAND with PETER SELG

THURSDAY to SUNDAY NOVEMBER 2-5, 2017

Download our full conference brochure at www.steinerbooks.org

KRZYSZTOF ANTO ´ NCZYK & CHRISTOPHER BAMFORD

BOARD & LODGING: $250 (Sunday night, additional $60)

For those staying elsewhere, daily breakfast, lunch, and dinner at the Center is $30/day (lunch and dinner: $24).

CONFERENCE FEE : $500 usd

[ TOTAL : $750, or $810 including Sunday night]

DETAILED INFORMATION, AND TO REGISTER: E-mail or call Paul Haygood: seminar@steinerbooks.org or 413 528 8233, ext 1.

CONFERENCE LOCATION: Auschwitz Center for Dialog and Prayer, 1 M. Kolbego St. 32-602, O´swięcim, Poland. Participants will be staying and the Conference will be taking place in the Center for Dialog and Prayer, a modern facility founded in 1992 in Auschwitz, about ten minutes walking distance from the camps. All events and meals will take place there. There are also a number of small hotels nearby.

COn CEntRA t IO nS

Early Childhood, Elementary Grades 1-8, Working with Special Needs

GRADALIS COURSES

INNER DEVELOPMENT

The imperative of inner work

WALDORF CULTURE

School governance, culture, leadership and community life

WALDORF METHODOLOGY

Monthly main lesson preparation

FIELD WORK

Mentoring and internship

TEMPORAL ARTS

Eurythmy, speech arts, music and spacial dynamics

VISUAL ARTS

Watercolor painting, drawing and sculpting

PHILOSOPHICAL FOUNDATIONS

Steiner’s world view and the evolution of consciousness

STUDENT STUDY

Accountabililty, standards and remedial approaches in Waldorf schools

t EAC h ER t RAI nInG

for independent & public waldorf school teachers

WhY GRADALIS? We support the working teacher ǀ GRADALIS courses provide the anthroposophical foundations of Waldorf education ǀ Our Faculty has years of experience teaching in both independent & public Waldorf schools ǀ GRADALIS training is taught over 26 months in 7 semesters, including: Three 2-week Summer Intensives in the Rocky Mountains; 4 Practicum Weekends; Mentoring & Internship in your own classroom ǀ Rich artistic instruction ǀ On-line Interactive Distance Learning (8.5% of program) provides monthly pedagogy & main lesson support through the school year ǀ Other: Summer Grade Level Prep week offered in Colorado.

Considering a meaningful career change? Become a Waldorf teacher! The movement needs teachers with a calling.

www.gradalis.com

We may seem new but we’ve been around!

Contact us at 303-518-0273

Donna Newberg-Long, Ph.D. | Bonnie River, M.Ed. | Thom Schaefer, M.A. | Prairie Adams, B.A.

Tim Long, MBA | Cristina Drews, M.S.Ed. | Hellene Brodsky-Blake, M.A. | Helen Lubin, M.A.

Lin Welch, M.A. | Gila Mann, M.A. | Karl Johnson, M.A. | Jane Mulder, B.A. | Janis Williams, M.E.

Sandra Kirschner, B.A. | Lee Sturgeon-Day | Thesa Callinicos | Susan Strauss | Tammra Tanner

Our Experienced Waldorf Faculty

Center for Anthroposophical Endeavors

A Place of Learning and Working in the World through Anthroposophy since 1982

Introducing

The North American Journal for the Mysteries of Technology

Mys

ech

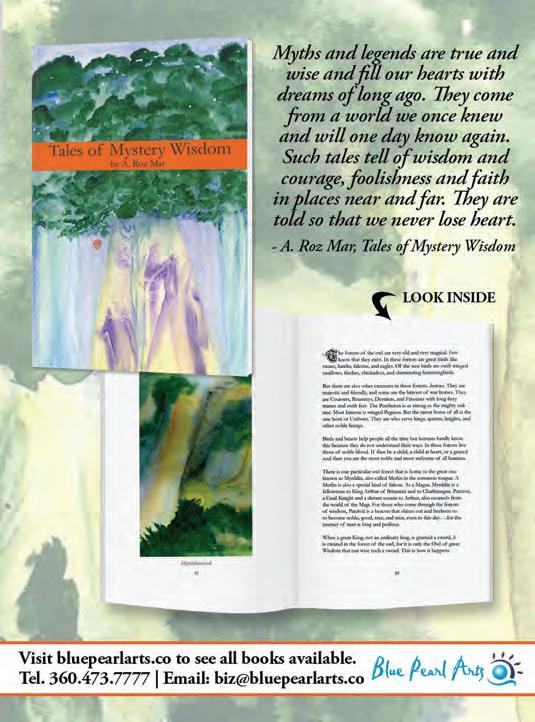

MysTech is a bi-annual journal dedicated to the serious task of finding a moral path towards technology that enables a "welding together of the human and machine." MysTech is dedicated to building the mysteries of technology. It begins as the catalyst for ideas as well as for research and development of this new technology. This should be of great interest for those working out of the stream of Anthroposophy who have wrestled with this issue of technology and the future of mankind. Just as there are many aspects to the development of ourselves and to Moral Technology, so there will be a diverse array of writings and research on the many aspects of the human condition as it relates to technology, the biological and physical sciences, evolution, as well as to the human etheric body and to the three human soul activities of thinking, feeling and willing.

Please join us for our inaugural issue of MysTech with articles from: Andrew Linnell, Christina Sophia and Brian Gray. Issues can be purchased through: rudolfsteinerbookstore.com/membership and select MysTech

Please also consider becoming a MysTech Member of CFAE. Through your yearly support, contributions are made to a fund for education, research and development in Moral technology.

Also Available through the Dr. Rudolf Steiner Bookstore in Seattle are Paul Emberson’s books:

• From Gondhishapur to Silicon Valley Vol. 1 & 2

• Machines and the Human Spirit

• The Coming Force - Journal of the DewCross Center for Moral Technology (inquire about available issues)

• Anthro-Tech - The Journal of the Anthro-Tech Institute for R&D of Moral Technology (inquire about available issues)

Please email Frank Dauenhauer at info@rudolfsteinerbookstore.com to inquire about the purchase of these books and Journals as they are for sale by request only.

The Dr. Rudolf Steiner Bookstore is host to: Sound Circle Center Student Bookstore and the Center for Anthroposophy Student Bookstore (Found under Training Courses)

summer-fall issue 2017 • 5

Dr. Rudolf Steiner Bookstore & MysTech are a 501(C)(3) nonprofit under CFAE

Connect to the Spiritual Rhythms of the Year...

The Christian Community is a movement for the renewal of religion, founded in 1922 with the help of Rudolf Steiner. It is centered around the seven sacraments in their renewed form and seeks to open the path to the living, healing presence of Christ in the age of the free individual.

Learn more at www.thechristiancommunity.org

E arly C hildhood, Gra des and H igh Sch ool Tracks www.bacwtt.org tiffany@bacwtt.org 415 479 4400 Embark on a journey of self development and discovery Study with us to become a Waldorf Teacher 6 • being human A sacred service. An open esoteric secret: The Act of Consecration of Man Celebration of the Festivals Renewal of the Sacraments Services for Children Religious Education Summer Camps Study Groups Lectures

14 Rudolf Steiner: Towards an Architecture of Social Transformation, by John Bloom

16 Colorado’s Angelica Village, by Renata Heberton

18 A Call to Garden, by Sally Voris

19 A Psychology of Soul and Spirit: An Anthroposophic Psychology, by David Tresemer, PhD

20 The Formation of MysTech, by Andrew Linnell

21 “In the Spirit of Steiner” Festival, by Marke Levene

22 arts & ideas

22 Pathos and Spiritus, by David Tresemer, PhD

25 Being Human and the Life Cycle of the Plant, by Tom Altgelt

28 Biography Work: Bringing Social Artistry to Life, by Patricia Rubano

30 “ What Society do we want, and how do we get there?” by Martin Large

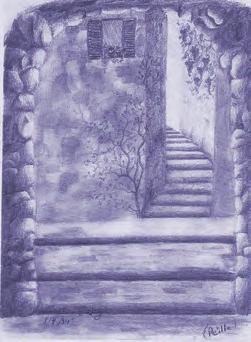

31 Gallery: Lois Schroff, artist, author, and teacher

36 Gratitude to Margaret Shipman and Rachel Schmid, by Peter Rennick

37 Professor Fritz Carl August Koelln: “Each day anew” by Neill Reilly

40 research & reviews

40 Anthroposophy, Quantum Physics, & Holistic Medicine’s Epistemology Crisis, review by Walter Alexander of Anthroposophy and Science 42 Sex Education and the Spirit by Lisa Romero, review by Daniel Mackenzie

47 news for members & friends

47 New Members of the Anthroposophical Society in America

48 New Members for the General Council: David Mansur, Joshua Kelberman

summer-fall issue 2017 • 7 Contents

8 from the editors 10 being human digest 13 articles on the internet 14 initiative!

45 No

6 Book Notes

Shore Too Far, by Jonathan Stedall 4

Kiely Retires

This is the Year,

Resiliency,

in Touch,

Members

First

Mid-Atlantic

Members Who Have Died

Uwe

49 Council Develops Values Statement, report by Dave Alsop 51 Judith

51

by Laura Scappaticci 52

Effort, Love, by Deb Abrahams-Dematte 52 Being

by Katherine Thivierge 53

Respond about the Library, report by Katherine Thivierge & Dwight Ebaugh 54

Annual

Gathering, Report by Dominic Nigito 55

56

Stave, MD • Rev. Richard Dancey 58 Patricia Thornburgh Zay Livingston 60 DoloresRose Dauenhauer 63 Rise Up: Life as a Labor of Love—ASA Fall Conference in Phoenix, Arizona

The Anthroposophical Society in America

General Council Members

John Bloom, General Secretary & President

Carla Beebe Comey, Chair (at large)

John Michael, Treasurer (at large)

Dwight Ebaugh, Secretary (at large)

Micky Leach (Western Region)

Dave Alsop (at large)

Marianne Fieber-Dhara (Central Region)

David Mansur (Eastern Region)

Joshua Kelberman (at large)

Leadership Team

Deb Abrahams-Dematte, Director of Development

Katherine Thivierge, Director of Operations

Laura Scappaticci, Director of Programs

being human is published by the Anthroposophical Society in America

1923 Geddes Avenue

Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1797

Tel. 734.662.9355

www.anthroposophy.org

Editor: John H. Beck

Associate Editors:

Fred Dennehy, Elaine Upton

Proofreader: Cynthia Chelius

Design and layout: John Beck

Please send submissions, questions, and comments to: editor@anthroposophy.org or to the postal address above, for our next issue by 5/15/2017.

©2017 The Anthroposophical Society in America. Responsibility for the content of articles is the authors’.

from the editor

Dear Friends,

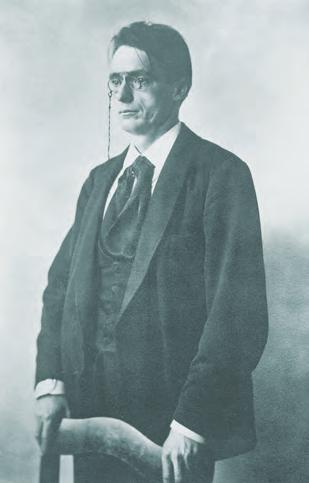

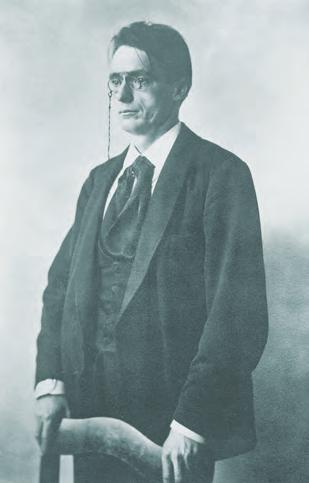

Our summer-fall issue of 2016 included a “Path to 2023,” something of particular meaning to students of Rudolf Steiner’s work. At the end of 1923, Dr. Steiner presented a new form for the Anthroposophical Society and a meditative verse, the Foundation Stone Mantra, by which to approach the universal cosmic image and reality of the human being. So a century later, at the end of 2023, many who have taken up and carried the far-reaching work initiated by Rudolf Steiner intend to renew the vitality of these two great initiatives.

The “Path to 2023” suggested working yearly through Steiner’s six basic exercises. 2017 would consider anthroposophy’s extraordinary gift of ideas and concepts. A century ago, in 1917, the most remarkable new results of Rudolf Steiner’s research would involve soul and body, individual and society.

First came a sharing of research that related the three forces of the soul or psyche to the arrangement of the human organism; this correlation has sometimes been called a “somatic psychology.” In this issue you will find a report of the progress of anthroposophic psychology as an initiative with tranings in the USA (p.19), and then a substantial book excerpt, “Pathos and Spiritus” (p.22), which illuminates the power of this discipline.

Steiner’s second discovery shared first in 1917 concerned the evolving and necessary threefoldness or tri-unity of the organism that is human society. We all can experience thinking and feeling and intention, or will, as dynamic aspects of our own inner lives, even if the expression “soul forces” is new to us. Very few of us, however, have ever entertained the question whether a healthy society must have multiple processes, laws, and governance, for different areas of life, in order to let strong individuals live together harmoniously. John Bloom’s essay (p.14) and Martin Large’s report (p.30) speak into this very timely concern which is now, of course, a global question.

Perhaps a bridge between these two, psychology and societal studies, is “biography work and social art”—a practical activity at the heart of anthroposophy. Patricia Rubano unfolds this work on page 28, Neill Reilly gives us a literary example of it in his tribute to Prof. Fritz Koelln (p.37). Colorado’s Angelica Village (p16) shows its intensive application in “intentional community,” it stands behind Sally Voris’ “A Call to Garden” (p.18), and Tom Altgelt sees it from another side, relating in word and image the human life

HOW TO receive being human, or to comment or contribute Copies of being human are free to members of the Anthroposophical Society in America (visit anthroposophy.org/join or call 734.662.9355). Sample copies are also sent to friends who contact us at the address below. To contribute articles or art please email editor@anthroposophy.org or write to Editor, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48104.

to the metamorphic life of plants (p.25). Daniel Mackenzie’s review (p.42) of Lisa Romero’s Sex Education and the Spirit extends the business of being human in another challenging direction. Jonathan Stedall perhaps rounds off the whole picture (p.45) with “No Shore Too Far,” poems of loss in which consciousness is heightened, and the loss finds new avenues of engagement.

In the last issue Fred Amrine gave us a stunning picture of Rudolf Steiner as a scientist overwhelmingly engaged with the discovery side rather than the proofand-justification side. Steiner himself noted that anthroposophy could not be “proven” in the modern materialist way, but that the more we know of it, the better it all hangs together. In this issue Walter Alexander’s review (p.40) of Anthroposophy and Science, written for holistic health practitioners not anthroposophists, shows a steady convergence of anthroposophy with the real scientific mainstream, even as popularized and commercialized accounts hang on to their deadly mechanical models. And as Andrew Linnell reports (p.20), even with the mechanical world we are creating there is a humane consciousness working to penetrate it with the goal of evolving “moral technology.”

It’s an exciting issue on the “path to 2023,” thanks to our contributors and the work they share. And the drama and beauty and seriousness of the painting of Lois Schroff echo this on the cover and in the gallery, while the painting by Eduardo Yi-Man on the back cover is meant to stir your enthusiasm for our fall conference in Phoenix in October. I hope to see you there!

Rudolf Steiner Library

Contact Information

Rudolf Steiner Library of the Anthroposophical Society in America , 351 Fairview Avenue Suite 610, Hudson, NY 12534-1259

(518) 944-7007 (voice & text)

E-mail: rsteinerlibrary@gmail.com

Hours: Wed–Fri, 10am–3pm.

Home page: www.anthroposophy.org/rsl

Library catalog: rsl.scoolaid.net

Questions? Contact us at info@anthroposophy.org or 734.662.9355, or visit www.anthroposophy.org

summer-fall issue 2017 • 9

ONLINE AT

Inspiration

HUMANITY’S PATH AND YOUR OWN. BECOME A MEMBER TODAY!

JOIN

www.anthroposophy.org/membership Insight

Community EXPLORE

John Beck

source a development.

dimensions the work and a wide Waldorf medicine, therapeutic disabilities. a environmental insight

WE INVITE YOU TO

EXPLORE

BECOME A MEMBER TODAY!

Benefits of membership

• Connecting with others

• The print edition of initiatives, arts, ideas,

• Membership in the community founded Switzerland

ANTHROPOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN AMERICA

Insight Inspiration Community

EXPLORE HUMANITY’S PATH AND YOUR OWN. BECOME A MEMBER TODAY!

WELCOME! We look forward to meeting you!

JOIN ONLINE AT www.anthroposophy.org/membership

young children.

• Borrowing and research the Society’s national

• Discounts on the Society’s and store items

• After two years of Society for Spiritual Science, Are there requirements Steiner’s work in the world.

JOIN Questions? Contact or

Beverly Amico of AWSNA writes: “We are living in an unpredictable world which is constantly competing for our attention, so much so that we need to consciously create spaces for rest. One of the best ways we can help children learn to work with anxiety is to help them find healthy pathways into sleep. In this webinar we will look at how the four lower senses (the touch sense, balance sense, movement sense, and “life” sense) create the foun-

Questions? Contact us at info@anthroposophy.org or 734.662.9355, or visit www.anthroposophy.org

Name Street Address City, State, ZIP Telephone Email Occupation and/or Interests

Date of Birth

The Society relies on the support of members and friends to carry out its work. Membership is not dependent on one’s financial circumstances and contributions are based on a sliding scale. Please choose the level which is right for you. Suggested rates:

❑ $180 per year (or $15 per month) — average contribution

❑ $60 per year (or $5 per month) — covers basic costs

❑ $120 per year (or $10 per month)

❑ $240 per year (or $20 per month)

❑ My check is enclosed ❑ Please charge my: ❑ MC ❑ VISA

Card #

Exp month/year 3-digit code

Signature Complete and return this form with payment to: Anthroposophical Society in America 1923 Geddes Ave, Ann Arbor, MI 48104 Or join and pay securely online at anthroposophy.org/membership

human

AMERICA

10

being

HUMANITY’S PATH AND YOUR OWN.

the

Anthroposophical a variety of opportunities sharing the possibilities

Insight Inspiration C

ANTHROPOSOPHICAL

IN

SOCIETY

being human digest

dation for journey and how they help children find greater peace and resiliency.”

anthroposophy.org

No to digitalization of early years

In a related area, ELIANT, the campaign to protect and make know “applied anthroposophy” in Europe, has been asking support on “YES to constructive investment in education! NO to the digitalization of early years!” Its goal of gathering at least 50,000 signatures by mid-May was easily surpassed. The full scope of ELIANT’s concerns is visible on their news page: eliant.eu/en/news/.

SOCIETY

Lilipoh: Dance of Shadows in America

The spring 2017 issue of Lilipoh featured two articles in the social area. Christopher Schaefer offered “Navigating Chaos in the Age of Trump: A Call for Discernment,” and Seth Jordan reviewed a new volume from the Rudolf Steiner Collected Works: Architecture as Peacework. Seth’s review is available online:

For all the virtues that Steiner praises in other cultures, I have never seen him say a positive word for nationalism—for the activity of exalting the virtues of one’s own culture above others. On the contrary, he says again and again how this cultural egotism it is a destructive impulse in the world. In Architecture as Peacework he says “Esoteric truths go dark the moment

we put the interests of any particular group ahead of the interests of humanity as a whole.”

lilipoh.com/articles/when-nationalism-rears-its-ugly-head/

MEDICINE

USA vs. Europe in Integrative Medicine

Last November the Lili Kolisko Institute alerted its mailing list to a new challenge:

The FTC, the Federal Trade Commission, has released today an enforcement policy that hits hard at homeopathic remedies.

Essentially it emphasizes that potentized remedies are based on no better than the science from the 1700’s and must in the future be labeled as such in order to not be misleading to the consumer?!!

With this attitude it is imperative to support work like the research done at the Kolisko Institute. Our work for the last seven years shows that the effect of potencies on biological systems can be physically demonstrated and statistically validated. Remedies based on those results may therefore in the near future be based on 21st century analyses rather the “the 1700s.”

From Europe the ELIANT newsletter had reported a year earlier on a survey of attitudes there:

Between 60% and 70% of all European patients make use of natural medicines and complimentary therapies—with or without the knowledge of their doctor—alongside conventional treatments. A British study concludes that treatments involving natural medicine are far more closely aligned to what patients expect from an effective treatment. They are looking for a combined conventional and complementary approach to treatment and are keen to engage actively in the therapeutic process. They would also like to discuss the combined approach to conventional medicine, with their doctor (Little CV, The School of Health & Social Care, 2009). This way of working is known as “Integrative.” ... ELIANT seeks

summer-fall issue 2017 • 11

to ensure that doctors do not dismiss anything that might benefit patients—never mind how subjective it may seem! Patients seeking a co-creative approach to medicine need to campaign for the integration of the various methods. Without a strong commitment from civil society this new approach and way of thinking will not take hold.

So two other calls to action resound, off stage, while healthcare holds the attention of American lawmakers. See Walter Alexander’s very important review—for holistic practitioners—of Anthroposophy and Science, on page 40, for the deep background of this cultural struggle.

ART

Eurythmy: Back to Carnegie Hall

With financial support given by forty-seven backers on Kickstarter.com, the Gabrielle Armenier Eurythmy Agency brought a performance by Lee-Chin Siow, violin, Svetlana Smolina, piano, and Gabrielle Armenier, eurythmy, to Weill Recital Hall at Carnegie Hall in New York City. That’s where some of the first American students of Rudolf Steiner lived over a century ago. The program opened with silent eurythmy and featured French music before intermission and Singaporean and Chinese music after.

The agency had also presented a program in 2016 at the Harvard Divinity School: “The Spiritual Verticality of Biodynamic Agriculture.” An expert in biodynamics, Philippe Armenier, a fine pianist, Brigitte Armenier, and organizer and eurythmist Gabrielle Armenier addressed body, soul, and spirit. “The spirit of biodynamic agriculture is to be sought in the imaginative consciousness of the human being who sets his artistic capacities to the service of the becoming of the Earth.” And, “Biodynamic agriculture is to agriculture what eurythmy is to music.”

Born in France in 1989, Gabrielle Armenier moved to California at the age of 11. Graduating from the eurythmy training in Spring Valley, NY (2012), she went on to earn Bachelor’s and Master’s in Pedagogical Eurythmy in Oslo (2013) and Stuttgart (2014).

She is working to develop projects which integrate the movement art of eurythmy in both professional and educational environ-

www.eurythmyagency.com/

being

human digest

anthroposophicpsychology.org COLOR

We are all made up of Body, Soul and Spirit. How these parts interact and are successfully integrated is the exploration of Anthroposophic Psychology. Join us in discovering “the possible Human Being.”

nourishesthe soul AAP puts SOUL backintopsychology.

ARTICLES ON THE INTERNET

Articles we could not include in the printed being human are published at www.anthroposophy.org/articles

About The Ten Commandments in Evolution: A Spiritual-Scientific Study, by Ernst Katz. Foreword by Virginia Sease. A background report by translator Agnes Schneeberg-de Steur.

“Florensky, The Russian Leonardo”; a review by Tyson Anderson of At the Crossroads of Science and Mysticism: On the Cultural-Historical Place and Premises of the Christian World-Understanding, by Pavel Florensky. Translated & edited by Boris Jakim.

“Professor Fritz Carl August Koelln: ‘Each day anew.’” An expansion of Neill Reilly’s article on page 37.

“The Foundation Stone Meditation as the Being of Isis/Sophia. Some Results from Working with the Foundation Stone Meditation,” by Bill Trusiewicz.

Honeymoon of Mourning : a review by Christiane Marks of a book of poems by Maarten Ploeger, translated by Matthew Dexter; with sample poems.

“Re-Membering Anthroposophy: Reflections on Membership and the Renewal of the Anthroposophical Society,” by Christopher Schaefer, PhD

“Two Books by Paul Emberson”: a review by Stephen E. Usher, PhD (economist).

“Anthroposophical Society: What Ails Thee?” by Fred Janney, with a meditation and pictures of the original Executive Council members of the General Anthroposophical Society.

ALKION CENTER Waldorf Teaching or Early Childhood Education 2-year, part-time diploma programs includes comprehensive Foundation Studies in Anthroposophy [can be attended separately] Art & Education Summer Courses in late June Alkion programs are recognized by AWSNA + WECAN ALKION CENTER | alkioncenter.org 330 County Rte. 21C, Ghent, NY 12075 summer-fall issue 2017 • 13 being human digest

IN THIS SECTION:

To open, John Bloom explores the radically humane social vision Rudolf Steiner unfolded a century ago.

Renata Heberton describes this vision come to life at Angelica Village in Lakewood, Colorado.

Sally Voris of White Rose Farm in Maryland offers a simple “call to garden” which expands the view into the life of soil and out to embrace the living Earth.

Anthroposophy is truly holistic, engaging inner and outer, and David Tresemer updates the picture of the initiative for anthroposophic psychology in the USA.

Describing the formation of MysTech in Seattle, Andrew Linnell reminds us that our relations with world-changing technology will also be intimate and moral.

Rudolf Steiner: Towards an Architecture of Social Transformation

by John Bloom

In introducing any aspect of Rudolf Steiner’s work, it important to be clear from the outset that through his insights he not only pushed the boundaries of what we know, but also how we know. He offered guidance for both through his lectures, writings, and leadership during his lifetime. His spiritual worldview was cosmological in scope, yet much of his work focused on practical ways to be in the world with awareness of how spiritual forces are at work in and through it.

He urged his audiences to be interested in current affairs and states of knowledge, as he was, even while he often pointed out their limitations. In particular, self-development as a basis for knowing the world and the capacity for imaginative or intuitive thinking were at the heart of his hopes for anyone interested in grasping the spiritual foundation of knowledge. This approach is as relevant to understanding the nature of the human being as it is to re-enlivening the fields of agriculture, education, natural science, the arts, or, in the case of this essay, economics, money, and how best to organize our societies.

Through lectures in his own time, and in the transcriptions and writings that remain for us, Steiner asked repeatedly to be understood rather than believed. I think he also knew that the path of understanding would be the more difficult of the two, especially because it requires discipline and a continual openness to self-development. Such inner work can lead to a transformation of consciousness informed by multiple modalities of knowing—observation, practice, and reflection—and a fluid sense of time and space measured by the reality of experience rather than by clocks and rulers. He encouraged all students of his work to follow scientific methodology, despite the fact that the phenomenon being studied might not fit the conventional definition of research material.

The key to all science, and therefore all knowing, is observation. But Steiner, deeply inspired by the scientific work of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, understood observation as a process of engagement, of seeing the physical reality as nothing more than a particular moment in a metamorphic process which itself can be “seen” in a context of time and space. This capacity for cognitive imagination, what Goethe described as “seeing his ideas,” plays an important part in working toward understanding Rudolf Steiner’s work, and it is a capacity patiently acquired.

At the core of Steiner’s work stands the human being. Each person is on a path of evolution unique to his or her individuality, a path that evolves across numerous incarnations. Each of us comes, according to William Wordsworth, “trailing clouds of glory.” This would be complicated enough to understand by itself, if only we did not need others in order to come into this world, into this body, at this time. But we do need others. We find ourselves on Earth, where we need to work with, live with, and love others, each of whom has a unique pre-history and a destiny path to map and follow that is different from our own. Thus, we struggle to find commonality, to find ways to get along, and to support each other along our paths.

No wonder social life, whether in a relationship of two or across a whole community, is complex. No

• being human

14

initiative!

wonder that conflicts and confluences in human relationships occur given the diversity and disjuncture of human beings and societies in different stages of cultural evolution. The invention and intervention of political boundaries and bodies of law, and the organic or competitive creation of economies simply to meet the needs of material existence add further layers of complication. Each of these domains—culture, polity, and economy—has its own logic, its own origins, and its own practices that have supported the evolution of individuals and humanity. At the same time, each of these domains has an equally powerful shadow side that, wrongly applied, has denied and oppressed human beings and the growth of human consciousness. If we are sensitive to currents at work in the contemporary world, we can sense that the shadows are quite present and active. Yet we lack clarity about each of the domains, and how they best function separately and together.

In the face of the catastrophe of World War I, Steiner articulated his vision of a threefold commonwealth as a way to bring peace and reorganize society based upon a principle of power with rather than power over. He linked freedom to the domain of culture, equality to the domain of rights and agreements, and compassionate interdependence (“brotherhood” in Steiner’s language) to the domain of economics. In doing so, he bridged his profound understanding of the threefold human being with an imagination of human beings organizing their public lives in congruent threefolding. By effecting this harmony between the inner integrity of each individual and a trifurcated high-functioning social organism, Steiner was putting in place the architecture of social transformation. Such architecture requires each individual to move past an ego-centric, self-interested view of the world to one motivated by interest in others and trust in the forces of reciprocity. He offered the tools for each person to do the inner work needed for this self-transformation and created an education that would support the development of such capacities for future generations. Steiner’s threefold principles provide a framework and tools with which to approach social life in a way that is regenerative, and inspired by an affirmation of the values of being human and being in community, albeit global in scale.

Within the threefold commonwealth, compassionate interdependence in the economic domain is probably least understood. Nothing in our current free market economic system speaks to an altruistic perspective, one which holds that we work to meet others’ needs as our needs are met through others’ work. Enlightened self-

interest, the notion that acting as if others mattered is in one’s best self-interest, has given way in current time to raw competitive self-interest. And, this self-interest has proven to be a failed, flawed, destructive concept.

As a guiding principle, self-interest may have worked at a time when moral and ethical boundaries, whether driven by church, community, or family, were operative in systems of self-governance. But, the fragmentation of such social forms and the atomization of individuals through the hyper-presence of technology have contributed to the atrophy of moral foundations in societies. As remedy, Steiner posited that all economic activity operates on the principle of brotherhood and sisterhood, and further, arises out of the interaction of land (or all natural resources), labor, and capital. The key point here is the interaction, particularly the production of commodities and services that emerge through those interactions. Contrary to how economics is typically conceived, what Steiner established was that the three basic elements are fundamentally not commodities in and of themselves. Imagine how different the world would be with the decommodification of land, labor, and capital. This is hard to grasp in an age when real estate and land is treated as investment rather than a means of production, labor is purchased on an hourly basis with workers regarded as replaceable parts in a production schema, and capital is used for nothing more than making more capital and is thus devoid of real value.

As part of this shift of economic paradigm, Steiner indicated that the management of interdependent practices was best done through freely formed associations. These associations would bring together producers, distributors, and consumers to determine how to steward natural resources, labor, and capital to assure that everyone’s material needs were met. As a result, setting prices was a key association function. Associative economics was Steiner’s antidote to what he perceived as the overreaching power of corporations and the state in managing economic affairs, which rightly belonged to the stakeholders most directly engaged in the economy activity, and who would reap the benefits and bear the consequences of their choices.

Steiner also understood money not as a thing but rather as a multifunctional servant—through purchase, loan, and gift—to the circulation of value and economic activity. Much of what he had to say resets these forms of money in their original purposes to support the creation of real value, and gives some powerful indications for how to work with money in a corrective healing way in our current distorted, inequitable system. One could look at

summer-fall issue 2017 • 15

money as a postmodern threshold experience, a mirror and magnifier of who we are as human beings. Money tends toward being anti-social in how we attach to it and it to us, even though each dollar is, as Steiner states, connected to all the division of human labor in the economy. In movement, in circulation, it reflects the pulse of material life. Money is both mystery and monster, misunderstood and misanthropic, a bearer of light and good intention, and evocateur of rapacious desire.

Money is as much a symptom of our inability to connect to the world as it is a symbol of just how deeply interdependent we are. Knowing money is a path to knowing oneself in relation to the economic world and its intersections with the political and wider cultural worlds. Money is social technology that pits self against the other and the world in the process of getting, and celebrates relationship in the world in the process of gifting and letting go. To see that we can live in multiple worlds and a multitude of transactions, maintain our integrity and recognize our interdependence through all of them, and still account for every penny, requires a new consciousness and a significant level of personal transformation.

Such transformation requires an architecture that acknowledges present reality with all its flaws, greed, corruption, and extreme inequity, and yet stands as a new structural system in which we can find aid and comfort, challenge and guidance, and above all, a way to live out of love and forgiveness rather than power and violence.

The task for our time is to bring practice and visibility to the social architecture that Rudolf Steiner described. What he articulated was that this structure is already there and further that we operate within it, but unconsciously. Through inner discipline, we can develop consciousness of the threefold nature of social life. Then, through that work, we can more fully inhabit the architecture of self and world in a way that brings about social harmony and supports a resilient structure—as the ancient cathedrals, temples, and mosques have stood the test of time—that is home to, honors, and inspires that which is spiritual in the human being and connects the individual with the wisdom of the cosmos.

John Bloom is General Secretary of the Anthroposophical Society in America and vice president for corporate culture of RSF Social Finance in San Francisco.

Adapted from John Bloom’s Foreword to Steinerian Economics by Gary Lamb and Sarah Hearn, Adonis Press, NY, 2014.

Colorado’s Angelica Village

It is the spring of 2016. A spicy aroma wafts out of the kitchen of 5520 W Virginia Avenue, Lakewood. Lodrigue pats a ball of chapatti dough as big as a soccer ball. Newly arrived from Uganda, he is making his home in the Denver suburbs, riding city buses, and attending the Waldorf school. He is joined by sister Bora, a slender eighteen-year-old with a knack for preparing chicken legs boiled in oil, and by younger brother Audry, more interested in the drumming studio in the garage than in cooking. These three joined the resident community of Angelica Village in May 2016, at that time including Amy and Renata from Denver, Diaz from Honduras, Alonzo from Guatemala, and Rosie from the Pine Ridge reservation in North Dakota.

Angelica Village was born in a small farmhouse across the street, home of Anamaria, Terri, and their toddler son Aaron. When a second baby was born, the farmhouse was bursting at the seams and, in perfect timing, the second farmhouse came up for sale. With extraordinary support from the Denver anthroposophical community as well as many other interested friends and donors, this house was purchased and a new chapter began in April 2016.

The vision of Angelica Village was born in Renata’s heart many years previously while still attending the Waldorf school. She carried it through college, obtaining her master’s degree in social work. It was nurtured further by her practicum at the House of Peace in Ipswich, Massachusetts, a community for refugee families and adults with developmental disabilities. [The story of the House of Peace was told in being human, summer 2013.]

Joining the workforce in Denver, Renata’s vision grew in urgency as she became painfully aware of the inadequacies of the social work system. A small support group formed to hold the intention of Angelica Village: to wel-

16 • being human initiative!

come those from all walks of life who want to create a community where all give what they can and receive what they need; where each individuality is held in the deepest regard and the collective strength holds all those who are engaged.

Specifically, the intention is to welcome those who have had the least opportunity to bring their full selves as a gift in this world, who have faced some of the dehumanizing experiences of violence, war, and homelessness. In the mainstream mindset, these individuals and families are seen as having little to offer the world and are placed in short term service programs which rarely serve their needs adequately. Families seeking refuge from war, individuals with special abilities, and parents who are homeless and single experience a unique set of challenges.

It is a harsh reality to recognize that all of these have been marginalized and underserved in many ways. In a world ravaged by war and displaying hostility toward those who are different, there is a growing sense of isolation for so many populations. When the strength of such individuals unites with a positive, peaceful community, the possibilities for healing and growth are immeasurable.

Communities dedicated to reversing these trends on micro and macro levels are critical. Built on the strengths of individuals from diverse backgrounds and focused on sustained relationships and mutual support, they can overcome structural oppression, celebrate differences, and work towards peace and healing. As a foundation for realizing this vision, Renata and her partner Amy trained as foster care parents for refugee youth and welcomed the first young people. Through the first year of rapid growth, they maintained full-time outside jobs while carrying out the tasks of parenting youth from diverse backgrounds. On any given day, this might include counseling, transportation, advocacy with social services and immigration, tutoring, instruction on how to ride the city buses, and driving lessons for the teenagers! All this on top of regular household tasks and particular needs like searching Craigslist for a reasonably priced set of drums for Audry and Lodrigue’s musical passion, or scouring the

city for jackfruit or cassava for a Ugandan evening meal.

The Farmhouse provides a home for the youth. A duplex down the road was purchased for two families coming out of homelessness; a long two years was spent fixing them up. One became the final home for a dear partner and board member Veola, who passed on due to terminal illness. After other patchwork arrangements, two families connected to Angelica Village who expressed a desire to participate fully and reciprocally in the community are moving in and making this duplex their home.

Two more youth have joined the residential community and additional adults and children have been called to join the impulse of Angelica Village, either as residents or frequent visitors, supporting in different ways while receiving what the community has to offer. The hope is to achieve the ideal balance between the individual and the greater community presented by Rudolf Steiner in 1920:

The healthy social life is only when

In the mirror of the human soul

The whole community forms itself

And in the community lives

The strength of the individual soul.

A first grant proposal seeks funds for a music and art studio, initially for the drumset that has become a focus of interest for the young people. (They are expanding their repertoire, and branching out to perform in city venues in local churches.) Individual donors are sought to make a monthly pledge. This will fund one full-time co-worker for the many daily tasks and provide some support for transportation, paying school, educational and vocational materials, diapers, food, clothing, and more.

Angelica Village is eager to grow into its full vision including homes to welcome more individuals and families, a community garden with animals, a youth and community art and music space, and a corner store cafe. We are also eager to infuse community activities and rhythms with therapeutic offerings. All are welcome!

Contact : Renata Heberton (renheb@gmail.com) or visit www.angelicavillage.org

summer-fall issue 2017 • 17

A Call to Garden!

by Sally Voris

Insights sparked by a deep conversation with Shelden Luz. In 1924, Rudolf Steiner gave a series of eight lectures to farmers in Poland who wanted to understand why the quality of their food was declining. Those lectures form the basis of biodynamic agriculture. Steiner framed agriculture in the context of the cosmos. He said invisible spiritual forces, acting through the stars, the planets, the sun and the moon, were vital to life on Earth. He asked farmers to imagine their farms as individual living organisms and he gave specific practices to build farm vitality.

After some ten years of farming using biodynamic practices, I noticed that the produce nearly popped with energy and flavor. It was easier to farm. I felt like I was now dancing with a living partner—the farm. I realized that plants don’t just grow out of the soil; they lift themselves (or are they pulled?) heavenward. When we are fed by such plants, we get that lift. To come to full flowering; however, the farm needs a farmer to mediate and balance its life processes. As the weather gets more erratic and extreme, it takes more will and skill to keep life on the farm dancing and breathing together!

In other lectures, Steiner spoke about how the Earth exists for the spiritual evolution of human beings. He outlined epochs and cycles of development in humans. Steiner foresaw that forces focused on materialism would become very strong in our time. Those forces deny spirit. It is our challenge, Steiner said, to develop our ability to balance spirit and matter through our hearts. Nutrition is essential to our spiritual development, he asserted. We need food that feeds our souls, our wills, and our spirits.

Our current industrial food system completely ignores this aspect of nutrition. The system produces commodities for consumers. It separates us from Nature—the source of our most intimate and immediate connection with Creation. Plants are the hands of God, said worldclass gardener Alan Chadwick. When we use our hands in the garden, we touch those hands. There is something in us that goes out to meet every living thing, said theologian Thomas Berry. The inner world of man and the outer world of nature go together, he asserted. We are meant to connect with Nature and be fed by her!

There are, however, tremendous forces seeking to hide this essential truth. Government subsidies and agricul-

tural institutions now encourage farmers to move their operations into controlled environments: hoop houses, green houses, barns, and buildings. Plants and animals have less access to fresh air and sunlight. Farmers use well water to irrigate their crops. Well water has predominantly Earth energy, whereas rain water contains vital atmospheric energy. Our food is losing its connection with the cosmic, spiritual forces in sunlight, fresh air, rain, and natural rhythms. We become less able to meet the challenges we face—less able even to see the forces that are drawing us downward.

We are the essential players here. We can awaken to that truth. Our birthright is connection, and so is our calling. We are co-creators of our world: what we imagine becomes the future. Can we hold a vision of abundance and hope? Or do we carry the images of despair and devastation that are swirling around us? Can we engage in work to restore wholeness to our lives and to our Earth?

It is not just a matter of where we get our food and how it is grown; it is also vitally important where we give to Nature, how we give to Nature, and why we give to Nature. What we do to Nature, we do to ourselves. When we dance with Nature as our partner, we reweave the web of life. We restore health.

White Rose Farm and its Circle were born out of love for the Earth and love for life. People will give to this work because they want to cultivate their own souls, they want to honor those who have come before and/or they want to prepare a space of love for those who are coming after. Let’s make love the foundation of the New World! There is much to celebrate and much to do....

Sally Voris (sally@whiterosefarm.com) is owner and operator of White Rose Farm, Taneytown, MD (www.whiterosefarm.com).

Sally combines gardening, storytelling and writing, teaching and organizing. She has been recognized regionally and nationally for work sharing the stories of her home community of Elkridge and the Patapsco Valley. After her mother died, she came to the farm that her parents had bought in 1966. She completed a year-long part-time training program in biodynamic agriculture at The Pfeiffer Center in New York in 2008. The farm was recognized as a mentor farm for the North American Biodynamic Apprenticeship Training Program in 2010. Sally believes that as we build relationships with each other and the world around us, we create invisible threads that link us heart to heart.

18 • being human initiative!

Peggy Adams with flowers at White Rose Farm

A Psychology of Soul and Spirit: An Anthroposophic Psychology

by David Tresemer, PhD

by David Tresemer, PhD

Rudolf Steiner is sometimes quoted as being against psychoanalysis and psychology. Quite the contrary! Many of Steiner’s lectures acknowledge and advance psychology as it was being developed in his time. His occasional criticisms must be seen in that context.

In a series of lectures called Pastoral Medicine (1924), Rudolf Steiner asserted that theologians and ministers should tend to human connections with spirit, medical doctors should attend to the needs of the physical body, and psychologists should attend to the needs of the soul. To that series of lectures, he invited theologians and medical doctors. At that time the field of psychology was inchoate, especially a psychology that recognized the importance of spirit.

Foremost among Steiner’s views on psychology is a series of nine lectures in 1909-1911 in Berlin, published as The Psychology of Body, Soul, and Spirit. His framework for anthroposophic psychology is a bit like Swiss cheese— an excellent structure with many holes. Had World War I not intervened, one feels that Steiner would have filled in those holes. Now it is up to us, through personal spiritual-scientific research, to do so.

Great teachers have furthered Steiner’s insights: Karl Koenig, Georg Kü hlewind, Christopher Bamford, Robert Sardello, Lisa Romero, and others.

A new initiative in anthroposophic psychology is growing in the United States. The Association for Anthroposophic Psychology (AAP) has recently graduated one group of twenty-two from our three-year certificate program (three seminars/year) in California, another group of seventeen in upstate NY, and is readying new three-year certificate programs in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. We seek to offer a bridge from mainstream psychology to an anthroposophic psychology. People come to these trainings and adjoining lectures seeking an alternative to mechanical views of human beings ( genes determine chemicals determine behavior, with consciousness seen as a side effect), both in normal development and when people have veered off a

path of healthy development.

AAP faculty includes authors published or distributed by SteinerBooks:

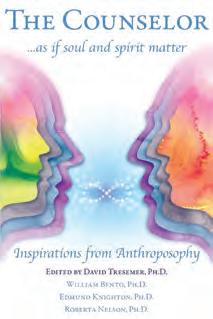

» David Tresemer (PhD Psychology, editor and contributor to The Counselor…As If Soul and Spirit Matter and Slow Counseling );

» Roberta Nelson (PhD Counselor Education, Licensed Practical Clinical Counselor, and Licensed Addiction Counselor, chapters in The Counselor);

» Edmund Knighton (PhD, Psychology, President of Rudolf Steiner College, chapters in The Counselor);

» and James Dyson (MD, co-founder of the Park Attwood Clinic, England).

William Bento (PhD, deceased in 2015), wrote Lifting the Veil of Mental Illness, and founded this initiative in the United States.

The trainings are geared to:

» licensed mental health professionals (seeking CEs, continuing education credits, and new perspectives);

» professionals in other fields (educators, life coaches, hospice workers, pastoral counselors, ministers, etc.);

» individuals seeking self-development, which is often sorely lacking in our lives as well as too often absent in training programs for the helping professions. This diversity has enhanced the dynamism in the experiential learning that AAP provides.

SteinerBooks and its imprints have offered an essential platform from which to launch a psychology of embodied soul and spirit in the United States. The courses rely on these conceptual frameworks and we are grateful that they are there. They form a foundation for the many embodied experiences in the face-to-face trainings that form the core of the AAP courses. For more information, see the books mentioned as well as information at www.AnthroposophicPsychology.org.

summer-fall issue 2017 • 19

David Tresemer, PhD, teaches in the certificate program in Anthroposophic Counseling Psychology, and with his wife Lila via the IlluminatedRelationships.com initiative.

The Formation of MysTech

by Andrew Linnell

For decades the Center for Anthroposophical Endeavors (CFAE) has fostered programs in the Northwest US that cultivate anthroposophical ideals and initiatives. One of its latest is MysTech, a new organization forged in partnership with Andrew Linnell, a forty-year veteran of the tech industry and now lecturer on the topic of the human being in regards to the mysteries of technology.

MysTech will further work to realize Rudolf Steiner’s indications on the development of a “mechanical occultism” in America and the English-speaking world. CFAE offers a MysTech membership and will publish a biannual MysTech Journal with thought provoking articles, viable research, and tangible results in the field of “moral technology.” (The first issue, for May 2017, is at rudolfsteinerbookstore.com/product/mystech-issue/.

Since Steiner’s time, relatively few individuals have taken up the topic of moral technology. Some of explorers in this field have been Paul Emberson, David Black, Joel Wendt, Nicanor Perlas, Tarjei Straume, and Andrew Linnell. During a lecture in Seattle sponsored by Dolores Rose Dauenhauer of CFAE in 2012, Andrew first realized the potential for a home for MysTech in Seattle, where some of the biggest tech giants are based. Since her passing in December 2015, her son Frank Dauenhauer has been managing director of the nonprofit which includes the Dr. Rudolf Steiner Bookstore; he has continued to sponsor Andrew as guest speaker and to promote this effort.

Rudolf Steiner indicated that technology and the coming incarnation of Ahriman1 should not be feared; rather Ahriman must be confronted in a healthy way to learn from him what will be needed for our future work. MysTech will work in transforming the Ahrimanic forces of our times to realize a true and inwardly moral way forward for humanity’s future with technology. In light of this, MysTech seeks stakeholders who, as supporting members, can help steer the research and the development of this future technology along a trajectory Rudolf Steiner indicated almost a 100 years ago. Possible future steps include:

1 Editor’s note: Physical research on material objects necessarily speaks of “things”; research in consciousness and spiritual reality requires us to speak of “beings.” In Rudolf Steiner’s research Ahriman is the cosmic being whose activity stands behind technology and materialism; Steiner expected him to appear as a human being early in the third millennium.

» Develop an interface to machinery that will filter impulses by the user based on their emotion (this already exists in research labs) initially and later on their moral intention. One target market is Exosuits, wearable robotics;2 others are anticipated.

» Explore motion-based physics.

» Replace atomism.3

» Understand how resonance happens across boundaries (e.g. between etheric and physical).

» Promote technology based on the ‘Keely machine’ or resonance.

Impulse: Observations by Rudolf Steiner

What is essential for humanity in this fifth postAtlantean period is to enter into a special treatment of great issues of life that have been obscured in a certain way through the wisdom of the past. I have already pointed this out to you. One great issue of life can be characterized in the following way: an attempt will have to be made to place the spiritual etheric in the service of outer practical life. I have brought to your attention that the fifth post-Atlantean period will have to solve the problem of how human moods, the motions of human moods, allow themselves to be translated into wave motions on machines, how man must be brought into connection with what must become more and more mechanical. ... In such situations the will is there to harness human energy to mechanical energy. These things should not be treated by fighting against them. That is a completely false view. These things will not fail to appear; they will come. What we are concerned with is whether, in the course of world history, they are entrusted to people who are familiar in a selfless way with the great aims of earthly evolution and who structure these things for the health of human beings, or whether they are enacted by groups of human beings who exploit these things in an egotistical or in a groupegotistical sense. That is what matters. It is not a question of the what in this case; the what is sure to come. It is a question of the how, how one tackles these situations. The what lies simply in the meaning of earthly evolution. The welding together of the human nature with the mechanical nature will be a problem of great significance for the remainder of earthly evolution.

— Rudolf Steiner, Individual Spirit Beings and the Undivided Foundation of the World: Part 3, 25 November 1917, Dornach, GA/CW 178

2 biodesign.seas.harvard.edu/soft-exosuits

3 wn.rsarchive.org/Lectures/GA320/English/GSF1977/19191223p01.html

20 • being human initiative!

First, there are the capacities having to do with so-called material occultism. By means of this capacity—and this is precisely the ideal of British secret societies—certain social forms at present basic within the industrial system shall be set up on an entirely different foundation. Every knowing member of these secret circles is aware that, solely by means of certain capacities that are still latent but evolving in man, and with the help of the law of harmonious oscillations, machines and mechanical constructions and other things can be set in motion. A small indication is to be found in what I connected with the person of Strader in my Mystery Dramas. These things are at present in process of development. They are guarded as secrets within those secret circles in the field of material occultism. Motors can be set in motion, into activity, by an insignificant human influence through a knowledge of the corresponding curve of oscillation.... The capacity to set motors in motion according to the laws of reciprocal oscillations will develop on a great scale among the English-speaking peoples. This is known in their secret circles, and is counted upon as the means whereby the mastery over the rest of the population of the earth shall be achieved even in the course of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch.”

— Rudolf Steiner, The Challenge of the Times, lecture 3, 1 December 1918, Dornach, GA/CW 186

Leaving a Legacy of Will

“In the Spirit of Steiner” Festival

Built from the company that brought the 1995 Mystery Drama and 2005 Symphonic Eurythmy tours to North America, Lemniscate Arts has been preparing a new play, The Working of the Spirit. This play addresses indications from Rudolf Steiner as to what would follow his four Mystery Dramas of 1910-1913.

This work is part of a larger conception. Much of humanity has not experienced that spiritual questions can be brought to the stage with grace and dignity and performing art of high quality. We have designed a world tour, In the Spirit of Steiner, through which to share such experiences. The scope of the task means that there is no way to rush to completion. We continue to work on both the integrity of the ideas and information that we will present and the artistic merits that such work can embody, and hope to be moving close to completion.

There are several important developments. First, we now feel free to separate the component parts of our festival idea. This has let us move forward with planning an international Symphonic Eurythmy tour: “What was kindled in the East, through the West takes on form.” In the performance a series of meaningful speech pieces will be woven together with symphonic music of Arvo Pärt. The first eurythmy and speech auditions will take place in Dornach in October 2017 with the tour anticipated to begin in October 2018.

Second, a new play has been written on the biography of Rudolf Steiner. We continue to refine it and will report in the future on a possible tour.

Third, Lemniscate Arts has sponsored the development of the Speech and Drama Studio in Freeport, Maine. The Studio will offer its first five-day speech course this August 6th–11th. It will be taught by Craig Giddens, Geoff Norris, and Kim Snyder-Vine. For information please contact Craig at crggddns@gmail.com.

For more information, contact Deb Abrahams-Dematte at deb@anthroposophy.org

We expect to report further concrete developments in the next being human. Thanks to all who have been in support of our work these past few years. For the whole group that has worked on this project, Marke Levene, Lemniscate Arts www.inthespiritofsteiner.com

summer-fall issue 2017 • 21

An opportunity to make a gift which will bring expression to your intention, and love for anthroposophy into the future.

PlannedGiving_QTR AD_FINAL.indd 1 10/25/14 6:44 AM

arts & ideas

IN THIS SECTION:

David Tresemer already described the initiative for anthroposophic psychology; now he shows its helping power.

Tom Altgelt extends the holistic weaving with parallel development of plants and humans.

To know and be known: Patricia Rubano tells us how “biography work and social art” meets this real human need.

Martin Large, a social activist from the UK who toured last November, reports what he saw and heard from uneasy Americans. Words about Lois Schroff’s paintings in the gallery are blessedly unnecessary!

For Neill Reilly biography and the life of the mind intersected with one great professor named Fritz Koelln.

Pathos and Spiritus

by David Tresemer, PhD

A chapter from The Counselor …. As If Soul and Spirit Matter, published by SteinerBooks

The Diverse Needs for Counseling: Response to Pathos

Counselors need to be aware of the full spectrum of needs, even if they can’t serve every situation. We can picture the wide range of human problems, concerns, and ailments along a dimension of pathology—from -ology, or logos (pattern), of pathos (passion, suffering, the human drama): pattern of suffering. We are all entangled in the pathos of life to some extent or another. Too much pathos makes us dysfunctional; too little means we are not prodded to grow. A counselor joins in another’s pathos through em-pathy.

Antipathy means that the counselor feels revulsion for the client’s pathos—thus anti (against) pathy (pathos); a reaction of rejection has been triggered in the counselor that the counselor should explore. Sympathy means that the counselor identifies with the pathos of the client; the counselor loses his or her Self. Empathy means that the counselor understands through resonance what the client is going through, as on a parallel track, yet does not drown in it along with the client. In every case, the counselor observes and feels the client’s pathos, with empathy the healthiest approach.

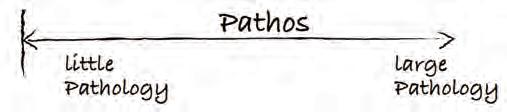

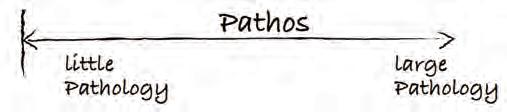

The pathos of human experience can range from little to large, creating a kind of Pathos Scale:

The popular Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM, version IV, Axis V) features a parallel scale that it calls the GAF, for Global Assessment of Functioning: High on the Pathos Scale means low functioning. The DSM-5 uses the World Health Organization (WHO) Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0. These continua are bumpy and not smooth, just like pathos, just like life.

The writhing knots of pathos grind their constrained and painful cycles over and over in our lives. We respond to pathos with maturity, with pathology, or with both. For counseling, we can observe a series of situations escalating along the continuum of a Pathos Scale, understood by the way the human being responds to pathos:

This is obviously simplified, yet helps us understand the continuum of pathos. At the left end, at little pathos, people have no problems, and do not seek counseling; they simply live their lives. Those who have simple problems seek mentoring from friends and relatives; an aunt or uncle becomes a helpful mentor; a helpful piece of advice keeps them going for a long time. Those who have more problems (higher on the Pathos Scale) seek to work with those nagging issues through personal growth, motivational workshops, trainings of all sorts, ropes-courses, self-help books, and life-coaching. These

22

• being human

problems can appear as large obstacles in the road of life, but amenable to change: one life-coach training site advertises a course, “How to Change Your Life in Forty-Five Minutes.” At this lower level of pathos, such a claim may not be ridiculous. Rhonda Byrne’s book and movie, The Secret, sold many millions of copies; its formula of positive thinking, in the tradition of Emile Coué and Ernest Holmes, can be very helpful at this level of pathos. At this end of the Pathos Scale, simple fix-its can sometimes work large changes.

Further to the right, “The Top 3 Ways to Fix your Love Life” ceases to be adequate. One finds more serious problems that require better-trained counselors who can use methods such as Solution Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT), or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), or Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT). It makes a difference if the counselor is thumbing through a manual (in their minds or, as has been occasionally reported, in the session), or is meeting a human soul present in the room. Though Albert Ellis’s Rational Emotional Behavior Therapy (father to the three methods just mentioned) can sometimes seem reductionist in its application—“All you’ve been saying is merely Irrational Belief #5”—Ellis in person was dynamic, funny, intuitive, and confronting. Indeed, he was able to make the “irrational beliefs” come alive, and accomplish great transformations in just a few sessions. Therapists with a formulaic approach can be effective with those with less pathos. Greater pathos demands a more mature counselor.

The person with more pathos—more serious problems—seeks ongoing psychotherapy, suggesting issues more deeply imbedded in the psyche. Even Martin Seligman suggested that learned helplessness took many retrainings—in his studies with traumatized dogs up to sixty—to undo.

As pathos becomes more severe, medications may be brought in. One of the issues of our time is that drugs are brought in far too early, at a level of pathos where the problem could simply be endured, rather than drugged. As Robert Whitaker has documented, the drugs drive people more deeply into pathos when they needn’t have gone there. Whitaker calls this an epidemic of iatrogenic (doctor-caused) mental illness, a monumental failure of medicine whose impacts will increase over the coming years. In the terms of this continuum, powerful drugs may push the user up the Pathos Scale. There may be appropriate times when medication must be used, as in intractable schizophrenia, or to help stabilize a person in order

to allow for their personal development through therapy. With that said, there is a rampant over-use through prescriptions and self-medication in the world due to the influence of pharmaceutical corporations. There is also the cultural push toward immediate gratification and numbing from any pain. In the coming years, we must ready ourselves to care for the potential that there will be many thousands of people impaired by over-use of medications.

For the most serious levels of pathos, the human being has to be contained and held much more strongly. Increased suffering can lead to outbreaks of violence against self and others. Institutions, from psychiatric hospitals to prisons, have been set up by society to deal with those suffering high pathos.

Each of these levels of pathos requires a different kind of counseling. Many counselors advertise that they can meet any human being and address any problem, but in truth they cannot. Each of these levels on a Pathos Scale requires a different understanding of the human being and different techniques.

A common assumption in counseling psychology is that we must move the client’s Pathos-meter from right to left, from high pathos to less pathos, from suffering to comfort. We assume that our duty is to enable the pursuit of happiness—stated as a right, along with life and liberty, in the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America—indeed, to maximize happiness! But is this the best goal?

Spiritus and Pathos

To understand anthroposophic psychology in relation to a Pathos Scale, another dimension becomes very helpful, that of Spiritus—low on the scale meaning less developed capacities of soul and spirit, and higher on the scale meaning more highly developed capacities of soul and spirit. Moving vertically accomplishes the various steps of human development—not only to what Erik Erikson called intimacy and generativity, or what Lawrence Kohlberg called post-conventional moral development, or what Sri Aurobindo called self-realization—but further up to what Aurobindo called God-realization, and anthroposophy calls manas, buddhi, and atma. The point here is that there are states of development of Spiritus that are known and described. (Chapters 4 and 5 of The Counselor give other criteria for understanding the development of the human being vertically.)

What happens when we consider a dimension of Spiritus in relation to a dimension of Pathos? In the fol-

summer-fall issue 2017 • 23

lowing, the central horizontal line of the Pathos Scale is exactly as we framed it above. What happens above and below that line, however, differs.

One could easily argue that these shapes should be adjusted this way or that. And certainly there are overlaps and shadings of each approach. However, the essential picture of this diagram yields several realizations.

First, the gradations between types of Pathos along the horizontal middle line, and thus the appropriate types of counseling, do not hold true at all levels of development of Spiritus. Any one technique claimed to be good for every person and every condition yields only a partial solution to symptoms and to the course of maturation.

We don’t have a GAF or WHO Assessment Scale for Spiritus. In truth, you don’t go up and down in Spiritus the same way that you go right and left with your level of suffering. Psychologists can create stress scales to measure right and left. In Spiritus, we often sample many different states all in the same day. This picture depicts the journey of the main mass of one’s individuality, the essential progress of one’s personal development.

Lifting your Spiritus through soul development does not ensure freedom from pathology. Artists, for example, can often have the challenge of high Pathos; because of high development of soul capacities, this Pathos can be brought into constructive expression (documented in Kay Jamison’s amazing book, Touched with Fire). In that top right area—large Pathos and high Spiritus—can be found the lives of heroes and heroines who have braved extreme difficulties and then gone on to motivate others to over-

come great adversity (as in David Menasche’s and Janine Shepherd’s stories); while apparently stories of overcoming pathos, the real stories are a growth in Spiritus.

This upper right corner includes the work of the Spiritual Emergence Network, pioneered by Christina Grof and Emma Bragdon. Their approach has been that people with high Spiritus, and undergoing high Pathos, whether temporary or long-term, can become severely dysfunctional. Because their crisis involves maturation of Spiritus, they should not be drugged but rather cared for in a special way to support that development.

For a long time, people have been seeking these highSpiritus experiences, and expect that they come with a higher level of pathos (that is hopefully temporary). Here’s part of a poem from Rumi, writing in the 13th century: I want that kind of grace from God that, when it hits, I won’t get off the floor for days. And when I finally do stagger into a semblance of poise, I will still need a cane and a shoulder to help me walk, and I will need great patience from any who try to decipher my slurred speech.1

Rumi expects the high-Spiritus “peak experience” to bring him high-Pathos. Today these symptoms would warrant medication; for Rumi, that would undermine the thoroughness of the foray into high-Spiritus.

The studies from the pre-drug era (prior to the entry of Thorazine in 1954) showed that the great majority of people who experienced depression or anxiety (or any of the other common debilitating diagnoses, including schizophrenia) self-regulated and rejoined their lives after three to twelve months (this research from Whitaker). These were episodes of higher Pathos on a rough journey to work out a lift in Spiritus.

Anthroposophic psychology has a unique ability to assist those who have attained high development of Spiritus. Every point in this map of Pathos and Spiritus requires a different quality and content of whole-soul conversation to meet the individual along his or her unique path of development. Understanding the journey in terms of the dynamics of soul and spirit assists one to find the appropriate counseling response.

Exclusively cognitive approaches to therapy are more successful with people who have developed their soul capacities to some extent. Those who have developed more in Spiritus veer away from mechanistic models; they be-

24 • being human arts & ideas

1 From Daniel Ladinsky (2002). Love Poems from God. New York: Penguin Compass, p. 83.

come more interested in approaches that recognize soul and spirit in action. A good cognitive psychologist adapts to these differences in development of Spiritus.

Over the millennia, levels of pathos have always ranged from little to large, though some say that times are getting harder. Anthroposophy asserts that Spiritus for the mass of humanity moves upward over the centuries. Though there have always been those advanced in spiritual development, as well as those very little developed, anthroposophy posits that the bulk of humanity is slowly advancing in spiritual development. This has great importance for a counselor’s task in relating to a person in need.

Perhaps the most important revelation of this picture is this: Anthroposophic psychology does not measure success as how far a client moves to the left—diminishing pathos, solving problems, reducing suffering, finding more happiness, adapting more readily to the client’s surroundings. Rather, progress is seen when one lifts in the dimension of Spiritus, the strengthening and realization of soul and spirit, moving upward in this diagram. The world is seen as a school for soul growth, rather than as a vehicle for pleasure. Each moves toward the realization that life is not only about individual happiness, but about a task for each and all (more in chapter 6). Progress is thus seen when soul/spirit realities are integrated into awareness, in this picture when one moves vertically. Horizontal movement becomes less important.

Of course, crippling pathos has to be dealt with, in service of the increasing ability to develop oneself through stages of sophistication of soul and spirit. The counselor helps the client draw nearer the purpose of a single human life, and all human life—and one finds this through the warmth and interaction of love.

Being Human and the Life Cycle of the Plant

by Tom Altgelt

There are numerous ways to approach the mysteries of life and of who and what we are as human beings. Out of my work with Rudolf Steiner’s remarkable plethora of practical indications and spiritual teachings, I have evolved a useful analogy that offers a lucid map to effectively aid us on our quest for inner development. It utilizes the age-old universal symbol of the lemniscate to illustrate the close relationship between the stages of the life cycle of a plant and our own spiritual growth.

My opening into ever deepening clarity began when I came in contact with Steiner’s foundational book, How to Know Higher Worlds. Steiner’s teachings regarding the

The Counselor …. As If Soul and Spirit Matter can be ordered from SteinerBooks or Amazon. There is more about anthroposophic psychology programs at AnthroposophicPsychology.org.

summer-fall issue 2017 • 25

David Tresemer, Ph.D., teaches in the certificate program in Anthroposophic Counseling Psychology, and with his wife Lila via the IlluminatedRelationships.com initiative.