being human

anthroposophy.org

rudolfsteiner.org

TENTH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE

to walk the human path (p.16)

farms healing the earth (p.22)

medicine more human (p.25)

gallery: Leszek Forczek (p.30)

art awakens higher life (p.37)

enter the (cosmic) child (p.39)

awakening community (p.42)

science and technology (p.45)

articles and reviews by Paige Hartsell, Karen Gierlach, Joyce Reilly, Walter Goldstein, Christoph Linder, Ricardo Bartelme, Walter Alexander, David Anderson, Harlan Gilbert, Christopher Schaefer, Frederick Dennehy, John Bloom, Deb AbrahamsDematte, Andrew Sullivan; poem by Christina Daub

a publication of the Anthroposophical Society in America summer-fall issue 2021 personal & cultural renewal in the 21st century

Planning for the life you want to live and for the world you want to live in. M o n e y a t w o r k i n t h e w o r l d i n t h e s e r v i c e o f t h e c o m m o n g o o d .

W e a r e a f i d u c i a r y , e t h i c a l l y b o u n d t o a d v i s e f o r o u r c l i e n t ' s i n t e r e s t s f i r s t a n d f o r e m o s t . O u r t a s k i s t o s u p p o r t o u r c l i e n t s t o f u l f i l l t h e i r i n d i v i d u a l l i f e ' s i n t e n t i o n s t h r o u g h f i n a n c i a l p l a n n i n g a n d a s s e t m a n a g e m e n t t h a t i s c o n g r u e n t w i t h t h e i r p e r s o n a l a n d s p i r i t u a l v a l u e s a n d a s p i r a t i o n s .

O

F i n a n c i a l P l a n n i n g

I n v e s t m e n t C o n s u l t i n g

P o r t f o l i o D e s i g n & M a n a g e m e n t

I n s u r a n c e P l a n n i n g

J e r r y M S c h w a r t z , C F P ®

B e r n a r d C . M u r p h y , C F P ®

K i m b e r l y M . M u l l i n , F P Q P ™

W e i n v i t e y o u t o c o n t a c t u s t o d a y !

E s t a t e P l a n n i n g U R S E R V I C E S I N C L U D E : A R I S T A A D V . C O M 5 1 8 . 4 6 4 . 0 3 1 9 | I N F O @ A R I S T A A D V . C O M

D igned for working teach s.

JULY 10-15, 2022 | DENVER COLORADO

Grade-Level Preparation (ECE to Grade 8) for the 2022-2023 school year

Experienced Waldorf instructors at each grade level and inspiring guests from the greater community. Classes cover a variety of information designed to ready the teacher with stories, art, academics and pedagogically appropriate content for the next grade level. Recommended for all teachers working in public or independent schools inspired by Waldorf pedagogy.

EXPLORING

Di rsity, Inclusi , and Acc sibility

IN NORTH AMERICAN SCHOOLS

SAVE YOUR SPOT:

Nationally Accredited Teacher Training for Independent and Public Schools

Inspired by Waldorf Principles

NEW COHORT BEGINS SUMMER 2022

DENVER, COLORADO | June 24th – July 15th

Gradalis training for Early Childhood and Grades Teachers is taught over 26 months, in seven semesters. Courses provide anthroposophical foundations, rich artistic training in visual & temporal arts, inner development, insights for child observation, and working with special needs. Plus, field mentoring, curriculum and school culture.

Includes: 3 two-week Summer Intensives; 4 Practicum Weekends; and on-line Interactive Distance Learning (8.7% of program) to support the working teacher with monthly pedagogical and main lesson support through two school years.

LEARN MORE: gradalis.edu

QUESTIONS 720-464-4557 or info@gradalis.edu

‘Teaching as an Art’

Education & Training

Accrediting Council for Continuing

ACCREDITED BY

anthroposophicpsychology.org Anthroposophic Psychology is born! EXPLORE the interpenetrating mysteries of Body, Soul & Spirit DISCOVER the illusive secrets of your own Psyche ILLUMINATE the journey from lower self to Higher Self In this 3-year transformational process you will be changed. Join us. NEW CERTIFICATE P R OGRAM BEGINS IN 2022 Visit our website for details. Inspiring Education Since 1967 Low-Residency Waldorf Elementary & Early Childhood Teacher Education Programs with MEd and MALS Option Scholarships Available, including Diversity Fund Scholarships • Specialized Subject Intensives • Courses & Workshops in Waldorf Education & Leadership • See Website for 2021-22 Events www.sunbridge.edu

Where would we all be without the Rudolf Steiner Library that holds and cares for the books that hold the ideals, ideas, thoughts, and words of Rudolf Steiner? The Rudolf Steiner Library is now open fully after a year of quietly waiting for members to be able “to just touch the books,” as one participant plaintively registered during this last year! Open and busy again—note our all-new logo above!

Interlibrary loans, curbside pick-ups and deliveries, and sorting through the abundant gifts of books, prints, and portfolios we have collected as bequests and personal library downsizings have made the RSLibrary as busy as it ever has been. Our members have been caring and understanding. Consider

Join Our Waldorf Teacher Training in Canada

Early Childhood Educator Training

Birth to Seven, with a Birth to Three Option

Grades Teacher Training

Summer Courses & Workshops

Early Childhood: Ruth Ker ece@westcoastinstitute.org 250-748-7791

Grades: Lisa Masterson grades@westcoastinstitute.org 949-220-3193

British Columbia, Canada | www.westcoastinstitute.org

joining them as a RSLibrary member. Find the rich considerations of Rudolf Steiner and many other authors here on broad topics of Anthroposophy, spirituality, relationships, meditation, and life on earth and under the stars.

As work continues to develop a more formal fundraising effort (sorting mailing lists and print schedules), contributions can be made via PayPal and the Rudolf Steiner Library homepage: rudolfsteinerlibrary.org

Pencil sketch, from the RSLibrary collection

and Resources

Parents and Educators The mission of the Waldorf Early Childhood Association of North America is to foster a spiritually-based impulse for the work with the young child from pre-birth to age seven. WECAN is committed to nurturing childhood as a foundation for renewing human culture. store.waldorfearlychildh o o d .org www.waldorfearlychildhood . o r g i n fo @waldorfearlychilhood.org Untitled-1 1 6/28/2021 7:16:34 AM Early Childhood, Grades and High School Tracks www.bacwtt.org tiffany@bacwtt.org 415 479 4400 Embark on a journey of self development and discovery Study with us to become a Waldorf Teacher

Books

for

Building the Temple of the Heart

Building the Temple of the Heart

Anthroposophical Society in America annual conference and members meeting October 7 - 10, 2021

Anthroposophical Society in America annual conference and members meeting October 7 - 10, 2021

Keynote Speakers: Michaela Glöckler, Brian Gray & Michael Lipson

Co-Sponsored by the Central Regional Council

Keynote Speakers: Michaela Glöckler, Brian Gray & Michael Lipson

Co-Sponsored by the Central Regional Council

registration at anthroposophy.org/fallconference

online with opportunities to gather in person

registration at ant h roposop h y.org/fallconferenc e on lin e with opportunit ie s to gather in person

95 years of ASA communications ten years of being human

the first newsletter for members (right), july 1927 the first journal for anthroposophy (2nd right), spring 1965 journals/newsletters (far right and 2nd row) 1976-78-88-90-96-2000

third row from left: 2007 news for members, 2009 evolving news, and first being human at Rudolf Steiner’s 150th birthday, 2011

anthroposophy.org personal and cultural renewal in the 21st century a quarterly publication of the Anthroposophical Society in America summer-fall issue 2017 Toward an Architecture of Social Transformation (p.14) A Call to Garden! (p.18) The Formation of MysTech! (p.20) Pathos and Spiritus Being Human and the Life-Cycle of the Plant Professor Fritz Carl August Koelln: “Each Day Anew” (p.37) Anthroposophy & Science (p.40) (see Gallery, page 31) being human anthroposophy.org rudolfsteiner.org personal and cultural renewal in the 21st century a quarterly publication of the Anthroposophical Society in America Division of Labor & Artificial Intelligence Orchestral Eurythmy: “Storms of Silence” Introducing Waldorf, Threefolding to Indian Non-Profits in the US (p.23) The (Mirror-)Image of Thought (p.28) Art & Humanity in Metamorphosis And the Earth Becomes a Sun (p.42) Swan’s Wings (p.44) Piercing Through the Veil of Karma The Concord School of Philosophy (p.51) Fall Conference: New Orleans! You’re Invited! (p.52) “Threefold Being” by Michael Howard (2016) acrylic on canvas (see Gallery, page 31) being human anthroposophy.org personal and cultural renewal in the 21st century quarterly publication of the Anthroposophical Society in America summer-fall issue 2016 Integral Teacher Education (p.20) The Lear Elegies What’s Wrong with Shakespeare (?) (p.34) The Currency of Self (p.37) The Brain is a Boundary A Path to 2023 (p.48) Tadadaho, the Peacemaker, and Hiawatha (l-r) Free Columbia Puppetry Project being human anthroposophy.org personal and cultural renewal in the 21st century a quarterly publication of the Anthroposophical Society in America spring issue 2014 Drawing with Hand, Head, and Heart (p.26) A Boy’s-Eye View of Mr. Kretz A View From the Ceiling Sound Circle Eurythmy (p.12) anthroposophy.org personal and cultural renewal in the 21st century “Calendar of the Soul, week 48” by Sophie Bourguignon-Takada INITIATIVE! Social Forums and New Ventures Remembering Fred Paddock Painting the Calendar of the Soul quarterly publication of the Anthroposophical Society in America – winter issue 2013

10 from the editors

51

16 The Twelve Senses: Sensing Justice in the Encounter, by Paige Hartsell

17 Biography & Social Art in the Time of Covid, by Karen Gierlach

19 Two Lives in Progress, reviews by Joyce Reilly

22

Open-Pollinator Future Lab, Youth+Agriculture, presentation by Walter Goldstein

25 Rudolf Steiner & the Art of Healing, by Christoph Linder, MD

30 The Relevance of Anthroposophic Medicine for Our Times (excerpt), by Ricardo Bartelme, MD, and Walter Alexander

30 Gallery: Leszek Forczek

37 The Unified Field, by David Anderson

39 Individuality and Diversity, by Harlan Gilbert

42 Social Ecology in Holistic Leadership, reviews by Christopher Schaefer, PhD

45 The Perennial Alternative by Frederick Amrine, review by Frederick Dennehy

47 “Michaelmas” – poem by Christina Daub

48 Opening Secrets: Rudolf Steiner, Spiritual Science, and Technology, by John Bloom

for members & friends

51 GEMS—An Inspiring Labor of Love, by members of the GEMS community

52 Hazel Archer Ginsberg Joins the General Council

54 Striving Toward Gentleness, by Deb Abrahams-Dematte

55 Thank you, Laura!

55 Welcoming New Members

56 Hartmut Schiffer, by Holly Richardson

57 Members Who Have Died

57 Elizabeth Ann Courtney Pratt, by Susan Weber

60 Elizabeth “Beth” Wieting, by Aaron Wieting

62 “Dear Anthroposophical Self,” by Andrew Sullivan

summer-fall issue 2021 • 9 Contents

16 to walk the human path

12 book notes

22 farms healing the earth

25 medicine more human

37 art awakens higher life

39 enter the (cosmic) child

42 awakening community

45 science and technology

news

The Anthroposophical Society in America

GENERAL COUNCIL

John Bloom, General Secretary & President

Helen-Ann Ireland, Chair (at large)

David Mansur, Treasurer (at large)

Nathaniel Williams, Secretary (at large)

Micky Leach (Western Region)

Hazel Archer Ginsberg (Central Region)

Gino Ver Eecke (Eastern Region)

Dave Alsop (at large)

LEADERSHIP TEAM

Deb Abrahams-Dematte, Director of Development

Katherine Thivierge, Director of Operations

being human

is published by the Anthroposophical Society in America

1923 Geddes Avenue

Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1797

Tel. 734.662.9355

Editor & Director of Communications:

John H. Beck

Associate Editor: Fred Dennehy

Proofreader: Cynthia Chelius

Headline typefaces by Lutz Baar

Past issues are online at www.issuu.com/anthrousa

Please send submissions, questions, and comments to: editor@anthroposophy.org or to the postal address above, for our next issue by 12/10/2021. being human is sent free to ASA members (visit anthroposophy.org/join).

To request a sample copy, write or email editor@anthroposophy.org

©2021 The Anthroposophical Society in America. Responsibility for the content of articles is the authors’.

from the editors

Dear Friends,

We’re celebrating ten years of being human. In 2008 the General Council chose to replace News for Members with a full-color magazine. We first put the name on the spring issue of 2011 honoring the 150th birthday of Rudolf Steiner. Many thanks to Marion Léon, James Lee, Fred Dennehy who edited the Library Newsletter, designer Seiko Semones, proofreader Cynthia Chelius, information manager Linda Leonard, and so many wonderful writers and artists!

This issue departs from its usual layout in order to celebrate the living, inspiring ideas of anthroposophy, brought by Rudolf Steiner, and the people who apply those ideas in all the fields of life. Anthroposophists are confident in the human ability to rise higher, to real freedom and love, and those who make our higher potential visible help others regain that confidence. We are mailing to a number of friends who do not usually receive these printed issues. Consider becoming a member at www.anthroposophy.org/join and help sustain this work.

Twice a year in these few pages we try to share the relevance of anthroposophy and its applications. Last issue we included a personal commentary on our current medical situation and its social-political context by Richard Fried, MD, a longtime practioner of Anthroposophic Medicine. This was not a “party line” on health questions and we noted that “contrasting experience-based views are always welcome.” In this issue we affirm Anthroposophic Medicine’s broadest essentials with a remarkable testimonial by the physician who brought it to this country as his life’s work, Dr. Christoph Linder, supplemented by an excerpt from a longer paper by anthroposophists Ricardo Bartelme, MD, and Walter Alexander. Walter is a past contributor and a professional writer on medical subjects who has tackled key questions like the “placebo effect,” which shows that consciousness actually works in and on the physical organism, and the true role of the heart in our circulatory systems. Anthroposophic Medicine is founded 1) on the full reality of the human being, 2) on the fact that every illness is personal , and 3) on the balancing of short-term and long-term goals in its therapeutic treatments.

There are many other wonderful pieces here. Many thanks to Casse Forczek for her work in creating the wonderful gallery. Also note the last page, “Dear Anthroposophical Self,” which means to help us stay alert and questioning even in our engagement with this great being, anthroposophy.

John Beck

In this tenth anniversary issue, Joyce Reilly reviews two autobiographies, Sunshine Girl: An Unexpected Life, and Gardens of Karma: Harvesting Myself among the Weeds, by two highly successful women, Julianna Margulies and Susan West Kurz. Each work touches the intersection of anthroposophy and celebrity, and each differently reveals the karmic interweavings of love and neglect.

Christopher Schaefer, whose life was changed many years ago after meeting Bernard Lievegoed and spending a year with the Netherland Pedagogical Institute, turns again toward Holland to review two books on spiritually based community development. The first, by Erik Lemcke, is Social Ecology in Holistic Leadership: A Guide for Collaborative Organizational Development and Transformation, an invaluable guide and workbook meant particularly for those already

practicing as consultants and facilitators. The second, by Harrie Salman, The Social World as Mystery Center, points to Rudolf Steiner’s insight that the modern mystery center resides in the everyday world of work and play. Salman focuses on the archetypal social phenomena of human meeting, conversation, and the working of karma.

My review of Frederick Amrine’s The Perennial Alternative: Episodes in the Reception of Goethe’s Scientific Work, finds cause for optimism in the continuing, even growing, influence of Goethe’s scientific method. Goethe’s practice has not only proven to be the enduring alternative to scientism, it has expanded beyond the disciplines of botany and color theory to become a way of seeing capable of interpreting anything that lives.

I have also reviewed a modern day trilogy of mystery plays, Angels at Bay, by Owen Barfield, written more than seventy years ago but only published this year. That review, too long for this issue, will be available soon in a new online PDF edition of being human

Though things are arranged differently for this special edition, being human has been featuring a research & reviews section for ten years. In looking back over the decade, I am struck not only by the quality of the publications we have reviewed, but the broad scope of the material. In addition to books about the history of spiritual science, we have had strikingly original works about philosophy, science, social ecology, spiritual practice, religion, art, and literature, as well as distinctively new fiction and poetry.

Most striking to me in overview are the threads connecting most of these books: a passion for inquiry, a readiness to see life within experience, and a willingness to begin each act of thinking anew. Nearly one hundred thirty years ago, a book entitled The Philosophy of Freedom made its appearance on the world stage, and it was an open question whether it would survive a generation, let alone more than a century. Today we see its endurance not only as a text relied upon all over the world, but as a method that brings together the most diverse interests through a shared practice of thinking, seeing, and aspiring.

Fred Dennehy

NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING

The General Council hereby gives notice that the annual general meeting of members of The Anthroposophical Society in America, Inc., will be held Thursday, October 7, 2021, 6:30–8pm Central Time via Zoom, as part of the annual conference. Topics of general interest will include the report by the Society’s treasurer on the state of the Society’s finances.

The ASA invites you to join the

Michael Support Circle

our major donor circle. THANK YOU to the 45 individual members, and to these organizations for their generous and on-going support:

Anthroposophical Society of Cape Ann

Anthroposophy NYC

Association of Waldorf Schools of North America

Bay Area Center for Waldorf Teacher Training

Biodynamic Association

Camphill School – Beaver Run

Carah Medical Arts

Cedarwood Waldorf School

Council of Anthroposophical Organizations

GRADALIS Waldorf Consulting & Services

Great Lakes Branch

House of Peace

RSF Social Finance

Rudolf Steiner Fellowship Foundation

Michael Support Circle members pledge gifts of between $500 and $5000 per year for five or more years. They help the Society to grow in capacity and vitality—the basis for increased membership, new learning opportunities, and greater impact in the world.

To learn more about how you can support the strength and sustainability of our movement, contact Deb at deb@anthroposophy.org

summer-fall issue 2021 • 11

Saint George Slays the Dragon, by Laura James

LegacyCircle

Erika V. Asten*

Betty Baldwin

J. Leonard Benson*

Susannah Berlin*

Hiram Anthony Bingham*

Mrs. Hiram A. Bingham

Virginia Blutau*

Iana Questara Boyce*

Marion Bruce*

Helen Ann Dinklage*

Irmgard Dodegge*

Raymond Elliot*

Lotte K. Emde*

Marie S. Fetzer*

Linda C. Folsom*

Hazel Ferguson*

Gerda Gaertner*

Susanna Gaertner

Ray German

Ruth Geiger

Harriet S. Gilliam*

Chuck Ginsberg

Hazel Archer-Ginsberg

Alice Groh

Agnes B. Granberg*

Bruce L. Henry*

Ruth Heuscher*

Christine Huston

Ernst Katz*

Cecilia Leigh

Anna Lord*

Seymour Lubin*

William H. Manning

Barbara Martin

Beverly Martin

Gregg Martens*

Robert & Ellen McDermott

Helvi McClelland

Robert S. Miller*

Ralph Neuman*

Martin Novom

Carolyn Oates

Mary Lee Plumb-Mentjes

Norman Pritchard*

Paul Riesen*

Mary Rubach*

Margaret Runyon

Ray Schlieben*

Lillian C. Scott*

Fairchild Smith*

Patti Smith*

Doris E. Stitzer*

Katherine Thivierge

Gertrude O. Teutsch*

Catherina Vanden Broek*

Randall Wadsworth

Pamela Whitman

Thomas Wilkinson

Anonymous (18)

* indicates past legacy gift

Legacy giving is an excellent way to support the work of the Society far beyond a person’s current giving capacity.

There are a variety of ways to make a legacy or planned gift. If you would like to learn more please contact Deb Abrahams-Dematte at 603-801-6484 or deb@anthroposophy.org

Space permits only a few full book reviews in each issue. Here we list some of the many others we encounter. Except as specified, the notes are from the publishers — Editor

Vaccination in the Work of Rudolf Steiner, by Daniel Hindes, 121 pp. (Aelzina Books, 2021)

Complementing his Viral Illnesses and Epidemics (2020), Daniel Hindes, school director at the Boulder Valley Waldorf School, has added a further volume of carefully translated and contextualized quotations. “Collected in this book are all of Rudolf Steiner’s statements on vaccination. Spanning over twenty five years, these extended excerpts are drawn from 15 separate volumes of the Collected Works. Several of these statements have never before been published in English. Newly translated from the latest German editions, they serve as an invaluable resource for anyone interested in exploring Steiner’s views on the topic of vaccination.”

To the Infinite and Back Again, A workbook in projective geometry, Part I, by Henrike Holdrege, 103 pp., 8.5x11 in. (Evolving Science Association, 2019)

This richly illustrated book provides countless exercises that foster clarity of thought and precision in imagination. It is a practice-oriented introduction to projective geometry, and in working through the exercises we learn to think in transformations and to experience a beautiful thought world in which ideas weave, grow, and metamorphose. The book leads in a careful step-by-step fashion to the challenging idea of the infinite. We learn to think this mind-expanding concept, a concept that opens up whole new ways of understanding. We begin to see that everything finite gains wholeness and coherence when we conceive of the infinite. As a fruit of the author’s many years of teaching, this workbook is intended for self-study and is a unique resource for high school and college math teachers

Henrike Holdrege trained as a mathematician, a biologist, and a science teacher. In 1998, she co-founded The Nature Institute. She strives in her work to bring deeper dimensions of the world–of nature and of our inner life–to experience. In the Institute’s adult education programs and courses and workshops locally, nationally, and internationally, her two main areas of focus are phenomenological studies of nature and mathematics as a training of thought.

12 • being human

www.anthroposophy.org/legacy

THAN K YO U! to these members, who support the Society’s future through a bequest or planned gift

photo by Javier Allegue Barros

Earthly, Transcendental, & Spiritual Logic: from Husserl’s Phenomenology to Steiner’s Anthroposophy, by Scott E. Hicks, (Amazon.com, 2019).

This book examines the problems of crossing from Husserl’s technique of directly viewing concepts, essences, and ideas to the full experience of crossing the threshold by means of spiritualizing thinking in the anthroposophical sense. It covers all of the places where Steiner mentions Husserl in his collected works and the early part of the book functions as an introduction to Husserl’s phenomenology for the general reader or for the anthroposophist. It begins with everyday consciousness and crosses into the realm of viewing ideas or essences directly. In the later chapters, there are a variety of studies which lead the reader on an adventure from strict scientific consciousness and perception of plants into the phenomenological reduction, and then over the chasm into the real life of living thinking in the etheric world. Through this, it becomes clear that phenomenological reflection does not take place in the same sphere as spiritual research. There are also several studies of Logic itself. These studies penetrate into what happens on the concept planes and in the living world during the processes of thinking, judging, inferring, and creating logical conclusions. The book also contains access to several new spiritual scientific creations and bridges which transform some of the basic logical laws and forms into anthroposophical living pulses and elements in the spiritual world. Most of the book takes place beyond the realm of mental images, following the work of Steiner’s Philosophy of Freedom. The text therefore contains several doorways for the active reader to enter into the new work of the anthroposophical movement in the spiritual world and all that such an approach entails.

THE ONE of the Emerald Tablet: Illuminating Ancient Cryptic Truths , by Anna Lups, MD, 152 pp., large format (SteinerBooks, 2017)

This unusual book escaped our notice until recently. In the Eurythmy Association newsletter Jeanne Simon-MacDonald wrote, “It is hard to try to indicate the depth, breadth and richness of this extraordinary book full of wisdom, anecdotes, and illustrations from Dr. Anna’s life and studies.” Author Peter Lamborn Wilson writes, “In the tradition of Paracelsus, Goethe, Novalis, Hahnemann, and Steiner, Dr. Lups weaves alchemy out of the art of an anonymous, brilliant six-year-old ‘Child Artist’ into a tapestry of symbolism, healing, and wisdom—including many surprises. A magical text!” And David Appelbaum, former editor of Parabola magazine, adds, “Anna

Lups’s marvelous memoir traces a pathway of cure, from health of the outer person to the inner esoterics of the soul, from allopathy to anthroposophic medicine. A lengthy sojourn through archetypal research to spiritual alchemy, she is guided by the questions ‘Who am I?’ ‘Where are my beginning and my end?’ and provides inspiration in the art of living to readers of all pursuits. A work of immense creativity.” —Editor “We are far more than we think we are.” A profound statement that slowly sinks in as a reality during the study of the drawings and the texts which become the material for the stories of all the members of humankind. Introduced through the autobiography of a female physician practicing in the Columbia County region of rural upstate New York, this is a book where the reader is invited to accompany the journey each human being will undertake into the earthly life and the wisdoms learned in the process of “becoming.” Filled with gratitude for this testimony of hope in the miracle that is human and the attention it draws to past

summer-fall issue 2021 • 13

scholars whose knowing was profound but often ignored, this book serves as a reference for future students who find them selves ready for the combined study of natural and spiritual science. Dr. Anna Lups lives in Columbia County, New York, where she has practiced private medicine continuously since 1967. Her background as a cardiologist and family practitioner has allowed her to experience a wide breadth of clinical care motifs. In 1979 she began the anthroposophic extension of medicine and continues to grow her understanding of patient care and alternative holistic medicine.

Knowledge of Spirit Worlds and Life after Death, As received through spirit guides , by Dr Bob Woodward, 166 pp. (Clairview Books, 2020)

“In the Newsletter of the AS in GB, Bob Woodward writes about how he came to work with his spirit guides and what his methodology is. The book follows on from his previous ones on receiving answers from his guides to his questions and gives a more rounded picture of these beings together with their conversations. He asks in a very straightforward way about what life is like after death, with each chapter on a particular theme such as how souls live in the spiritual world, what they actually experience and whom do they meet. Each series of conversations is followed by a commentary and passages from Steiner which seem to corroborate what the guides have described. They give us more detail about the periods fairly soon after death, whereas

incarnations for instance. The book concludes with Bob making contact with his deceased father and noting down their conversations which take place 25 years later and after the kamaloca period. Doubtless Bob felt he was experiencing his father’s presence, but for the reader a shared memory or two would have been helpful as discarnate beings may not always be who they claim to be. It is very courageous to be so forthcoming about one’s spiritual experiences, we can appreciate Bob’s sincerity, concern for accuracy and desire to reach out to a wider public. We are urged to develop our own connections with spiritual helpers, as Steiner does refer in various places to a plurality of beings who want to assist those on the earth.” —Margaret Jonas, librarian at Rudolf Steiner House, London, for many years, is the author of The Templar Spirit and The Northern Enchantment and editor of anthologies by Rudolf Steiner on these subjects.

Exploring Themes in the Calendar of the Soul, by Luigi Morelli, 200 pp. (iUniverse, 2021)

“This work explores themes as they emerge in Rudolf Steiner’s Calendar of the Soul, first as they appear during the two halves of the year, spring/summer and fall/winter, secondly in relation to the mid-season quadrants, formed by the verses of so-called cross 7, which divide the year in four equal parts, centered around the times of the equinoxes and solstices. One of the main threads continues the exploration of the polarity thinking / intuition as it emerges from the work of Karl König, and places it in relation to other ones that emerge throughout the year, such as the expressions of feeling, memory, will, cosmic thinking and cosmic Word and their relationship to the human being. During spring and summer we follow the ascent of cosmic life, cosmic light and cosmic warmth, and cosmic Word as gifts bestowed upon the human being by the cosmos. During the cold time of the year these are inwardly elaborated by the human being, conscious of her place in Earth evolution and of her relationship to the Christ impulse, and given back to the cosmos. The Calendar thus exemplifies how the human being is both connected to the movements of the seasons, but also partly independent in having

14 • being human P a c i f i c E u r y t h m y J O I N A P A R T - T I M E E U R Y T H M Y T R A I N I N G I N I T I A T I V E I N P O R T L A N D , O R E G O N NEW CLASSES BEGIN SEPTEMBER 2021 For more information visit: PacificEurythmy.com Email: pacificeurythmy@gmail.com

to exert inner initiative that counters natural tendencies.”

Editor’s note: This latest in Luigi Morelli’s substantial series of books is available at Amazon but also at millenniumculmination.net where the full list may be available for download and there are some translations in Spanish.

The list includes 2020’s Illness and the Soul; Tolkien, Mythology, Imagination and Spiritual Insight ; and books on Tolkien and Owen Barfield, Aristotelians and Platonists, Karl Julius Schröer and Rudolf Steiner, social questions, and spiritual turning points of both North and South American history, the last two available from SteinerBooks. The author’s bio: “Cultures have been a great part of my upbringing, since I’m American born, part Italian, part Peruvian, mostly grew up in Belgium, and have lived the longest in the US. I have long had a passion for social change from a cultural/spiritual perspective. This has brought me to working with the developmentally disabled in the intentional, holistic communities of Camphill and L’Arche International, and also in the mainstream. I have lived in intentional cohousing for the last ten years... actively involved in community building and process facilitation.”

Fire the Imagination: Write On! by Dorit Winter, 204 pp. (Waldorf Publications, 2017)

How can teachers develop strong writing skills in their students in classroom and in life? Clarity and precision, empathy, and calls-to-action happen when the writing stimulates a clear response. Capacities in writers take practice and focus and refined skill in a teacher. Fire the Imagination— Write On! is a vehicle for developing those teaching skills that, in turn, develop writing skills in the young and old. The rigor of the lessons makes for engagement and plain old fun in working hard on good writing. Just the ticket for middle and high school youngsters—effective with adults as well!

Dorit Winter, MA, brings a cosmopolitan background to all her undertakings. Born in Jerusalem in 1947, she attended kindergarten in Zürich, primary school in Johannesburg and Cape Town, and junior and senior high schools in New York City, graduating from the Rudolf Steiner High School in 1964. Dorit began her Waldorf career in 1973 as a German and class teacher at the Rudolf Steiner School in New York City. Seven years later, she joined the Great Barrington

Rudolf Steiner School, where she coordinated the founding of a new high school. In 1989 she became founder and director of Rudolf Steiner College’s satellite teacher training program in San Francisco. In 2001 she accepted the directorship of Bay Area Center for Waldorf Teacher Training, from which she retired in 2014. Her Waldorf activities can be found at www.doritwinterwaldorf.com and her work as a painter at www.doritwinter.com

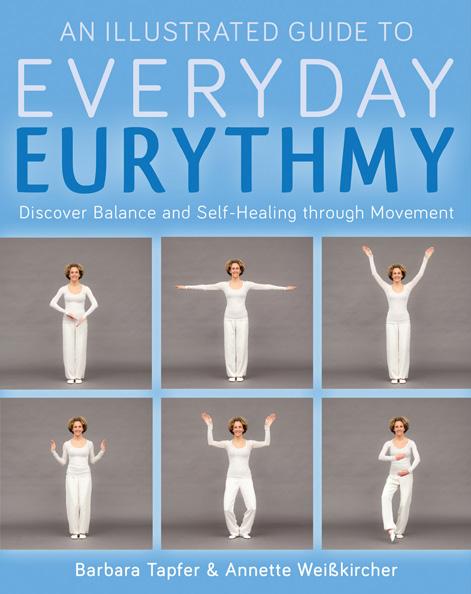

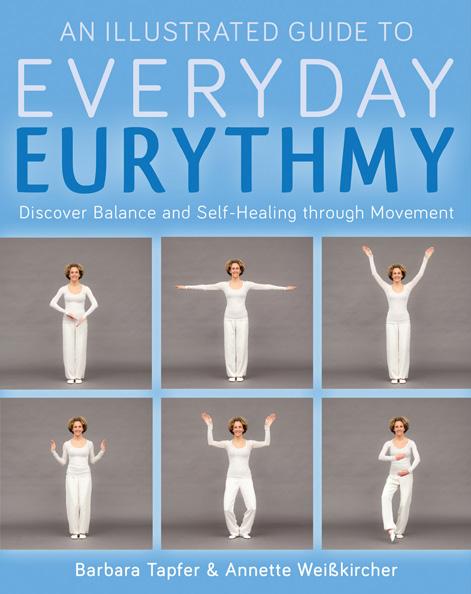

An Illustrated Guide to Everyday Eurythmy: Discover Balance and Self-Healing through Movement, by Barbara Tapfer and Annette Weisskircher, 168 pp. (Floris Books, 2017)

Discover the art of eurythmy with this richly illustrated step-by-step guide. Eurythmy is a compelling method of bringing balance and harmony to our body, soul and spirit through a series of rhythmic body movements. For the first time, this unique book captures these gestures visually through dynamic photographs, which clearly demonstrate the core movements of eurythmy therapy. It has long been recognized that we can direct powerful physical and mental changes within ourselves through specific movements of our bodies, as stated by advocates of yoga and tai chi. The authors of this original book are experienced eurythmists, who describe and illustrate the core speech–sound exercises: vowel exercises, consonant exercises and soul exercises, which include love, hope and sympathy. This book is not a replacement for a qualified eurythmy therapist, but is intended as guidance and orientation for patients practicing on their own, after a few initial sessions with a therapist, or for more experienced eurythmists. Contents:

Vowel Exercises

A – (ah) Opening; E – (eh) Crossing; I – (ee) Reaching out from the Heart Space; O – (oh) Circular Enclosing;

U – (oo) Bringing Together

Consonant Exercises

B – Enveloping and Protecting; P – Enveloping and Drawing In; D – Gently Descending; T – Inwardly Radiating; F – Airborne Intention; G – Calmly Repelling;

K – Energetically Repelling; H – Broadening and Freeing;

L – Wavelike Transformation; M – supple Sensing;

N – Quickly Withdrawing; R – Revolving; S – Enlivening and Formative; Sh – Narowly Spiralling Upward

Soul Exercises

A – (ah) Reverence; E – (eh) Love; U – (oo) Hope; Yes / No; Sympathy / Antipathy + Further Resources

summer-fall issue 2021 • 15

Fire the Imagination Write On! imagination is not to existence, but rather to really exists. Wadsworth Longfellow of all ages in lively, precise creatively, enthusiastically? classroom experience, is a shows teachers how to guide detailed, clear-cut descriptions. tracking homework, managing evaluating written work are also emphasis is on middle school, to high school and beyond. lessons, samples of students’ ideas and exercises to avoid sentimental, the unbelievable and teachers and their students. yet clear thinking leads to stronger sentences, and more and essays. For college, for invaluable skills.

Fire the Imagination: Write On! Dorit Winter Waldorf Publications 9 781943 582051

Dorit Winter

place between the animals and the angels. It is a transformative new insight: we are an essential part of world design.

Anthroposophy, said Rudolf Steiner, arises as a need of the human heart, and it arrived in human culture at a stage in

there is something higher than ourselves.

Alongside key insights and guidance in self-development, Rudolf Steiner reminded us that we actually will find our higher selves in the world around us: in each other, and in community.

The Twelve Senses: Sensing Justice in the Encounter

by Paige Hartsell

by Paige Hartsell

Justice has been at the center of conversation, policy, and mass gatherings over the last year. For many people it has been an ever-present theme over generations as our world struggles to understand what it means to bring equity to fruition across race, class, and gender, cultures, the natural environment, and religious and spiritual traditions. What exactly do we mean by justice? What does justice look like in relation to our Self, the world, and the environment, and as we encounter one another?

On August 11-15, Threefold Educational Foundation and partners is hosting “The Twelve Senses: Sensing Justice in the Encounter.” This international online conference will examine this question of justice in relation to the lower, higher, and highest senses. There are many lenses through which to look at the development of the twelve senses posited by Rudolf Steiner as they relate to such topics as education or agriculture, for instance. Last year, a Twelve Senses conference entitled “A Step into a Human Future” marked the 60th anniversary of Karl König’s lectures on the senses given at the Threefold Summer School in Spring Valley, New York, and the 80th anniversary of Camphill in the United States. Recollecting Steiner’s charge that anthroposophy and human spiritual and social development is not a static task, the conference planning committee explored what keeps the König lectures relevant today. To heal the trauma and unrest of our time, we must be in authentic relationships with those around us. The development and health of the twelve senses is critical for meeting the challenges in all realms of our lives. Integrating the well-developed senses grows our capacity to live into the I-being of another person, to experience compassion, and to be in service to the

world. This year’s conference will examine the theme of justice in relation to the senses in their three groupings and in their capacity to sense justice in the encounter in the inner life of the Self, in the world, and the environment, and in our interactions with other beings

We are honored to have keynotes offered this year by Dr. Lakshmi Prasana, Jean-Michel Florin, Michael Kokinos, and Joan Sleigh. Workshops will fill the middle of each day and cover a wide range of topics, including curative education, the understanding of the senses in the Algonquian/Abenaki language, movement and clowning, inner work, social activism, fiber crafts, education and technology, and more. Each day will include a panel discussion with the day’s workshop leaders and guests, and we will have two additional panels on the topics of curative education and social activism. Presenters this year include faculty and students from Raphael Academy (New Orleans), faculty from the Fiber Craft Studio, Dottie Zold and Frank Agrama of ALIANT Alliance, Robin Schmidt, Carrie Shuchardt, Sharifa Oppenheimer, Elizabeth Frishkoff, and Algonquian/Abenaki language teacher Jesse Bowman Bruchac, individuals working on the frontlines of society in the fight against oppression, faculty from Camphill Academy and The Camphill School, and faculty from the Otto Specht School (Chestnut Ridge, NY). Recorded pre-conference lectures by Richard Steel and Jan Goeschel will be available for registrants. The full program and registration information can be found at www.twelvesenses.org.

Karl König wrote that if we are to strengthen our humanity for living into the future, we have to understand the three highest senses ( A Living Physiology, trans C. Sp-

16 • being human

roll, Camphill Books, 2006, p. 254). Although we can find evidence of honor and respect for our common humanity in the world, we also must acknowledge that the capacity for building the recognition of our common humanity is under attack . While our twelve senses are developing simultaneously, they are also de pendent on and build on one another in order that the human spirit can flower to its utmost in this present life. It is only through an understanding of ourselves and the knowledge that we are endowed with these higher senses that “will awaken us to our reality” (p. 160), as well as deepen our understanding of justice as a moral deed of our choosing.

In developing our senses, we can strive towards objectifying our responses to sense impressions when faced with the challenges of what it means to be human in this world that is both horrifying and indescribably beautiful. We can free ourselves from biases based on our sympathies and antipathies so that our encounters and interactions are unfettered by our untransformed soul capacities. About the United States, König wrote in 1960 that if we Ameri-

cans awakened to the reality of our highest senses, It would blow through the continent like a mighty, rushing wind...and more and more people [would] become able to see the spiritual image... in every human being, in every growing child. This is what is so sorely needed all over the world (p. 161).

What does justice mean to you? Please let us know! Email your thoughts in fifty words or less to: twelvesenses@threefold.org

Paige Hartsell has been involved with anthroposophy through education, agriculture, and community living since 1994. A former Waldorf high school teacher, she worked for several years in both curative and farm education. She is currently pursuing masters degrees in Divinity and Social Work with concentrations in Islam and Interreligious Engagement and Community Organizing through Union Theological Seminary and Hunter College in Harlem. She is an intern at the Kairos Center for Religions, Rights, and Social Justice where she is researching food access and security issues in the US as they relate to the Poor People’s Campaign analysis of the five interlocking injustices of systemic poverty, systemic racism, militarism, environmental degradation, and the false moral narrative of religious nationalism.

Biography & Social Art in the Time of Covid

by Karen Gierlach

“I

The last eighteen, enormously challenging months have awakened the impulse to provide a balm during this time of suffering and loss. To our great joy, the social art of biography was able to be one of those balms.

When everything shut down in March 2020, facilitators from the Center for Biography and Social Art were part-way through our plans for the rest of the 2020 school year. Until then, we had greatly enjoyed visiting fourteen different Waldorf schools around the country each year,

presenting Awakening Connections: Creating Community, a three-part series of workshops. These were made available, free of charge, through a generous grant from Janey Newton to the Center.

All our workshops had taken place in artistically arranged indoor spaces and relied greatly on small group, face-to-face human encounters. Initially we questioned using Zoom for that kind of a workshop. It seemed really necessary, however, to provide an opportunity to meet others in heartfelt, open, and sincere ways during a time of the greatest social separation we had ever encountered. Two of our facilitators, Kathleen Bowen and Jennifer Brooks Quinn, were inspired almost immediately to launch two-hour Zoom workshops to the general public

“I feel heard.”

“So nourishing!”

remembered: I have tools of my own...”

summer-fall issue 2021 • 17

called “How Are You.... Really?”

The response was so great that they had to offer this workshop many times over. Additional titles were added to continue this work: “ Tending the Hearth,” “Deepening Courage,” “And Now What?” Because Jennifer speaks Spanish, they were expanded to include our friends in Mexico. We also returned to the schools we had visited in person with a two-hour Zoom workshop of support, titled “A Different Kind of Call” to distinguish it from the overload of organizational and teaching Zoom calls that were necessary for schools to remain open.

Within the two-hour format—which always passed very fast!—we began with an introductory exercise in the full group (e.g., show us an object of your choice and tell us your connection to it). More prompts followed which might lead to a drawing (sketch the first meeting with an important person in your life), some journaling (“I remember, I remember...” ), or commenting on a postcard image or a line from a poem (reflect on why you chose that image or line).

These doorways access memories in an open-ended and non-threatening way and place them outside our heads, allowing us to see them more objectively. Following the prompt, people shared what they discovered in groups of two or three. After each exercise the whole group heard comments about the other small group experiences. The session was rounded off by participants sharing their “takeaways” from the experience.

“I

was able to listen to my own thoughts.”

“This deepened my understanding of these times.”

“Important to hear another perspective...”

By the end of 2020, over sixty such workshops had kept several facilitators very busy. Beginning in 2021, with new funding to bring workshops to Waldorf schools and to anthroposophical branches, we developed seven more two-hour Zoom topics from which those groups could choose. Again, the response was most enthusiastic, and eventually four of us worked with around fifty communities from all over North America.

Teachers and parents were thrilled to meet outside of business-only meetings in the heartfelt ways they missed and said they sometime lacked even before Covid. The branches often invited members who lived far away to attend our workshops, leading to many new meetings. Even members of the same communities welcomed learning new things about each other’s interesting lives.

“A network of stars – we have so much in common.”

“An open-hearted communication.”

“I was amazed that this works through technology.”

We learned several things from presenting so many more workshops. Using Zoom with the right intentions and in an artistic way can provide meaningful experiences similar to in-person meetings. And it enabled people from all over the country and the world to meet. For many it had been difficult or impossible to experience a biography workshop before because they lived too far away.

We also learned that if we stay flexible and listen to what is needed in the world, biography is a very adaptable, yet profound social art. By taking an interest in each other it can help people connect and find commonality, even when outwardly they seem very different.

“Renewed empathy through listening to the stories...”

“Astonished in such a short time to recognize the grace of darkness.”

“I witnessed my wonder at being human and being with other human beings.”

“I was able to connect on a heart level with new people.”

By practicing listening to others, while putting aside our own opinions, assumptions and judgments, we are developing tools which can be used everywhere. Is this not what our times are calling for as we negotiate all the divisions that keep arising among people, even within our own anthroposophical communities? As Rudolf Steiner said already a century ago,

“The longing to be seen and heard in our full reality has arisen in every human soul since the beginning of the 20th century and will grow increasingly urgent.”

For information about workshop offerings in the fall, contact center4biography@gmail.com

Karen Gierlach (pkgierlach@gmail.com) has facilitated biography and social art workshops since retiring from Waldorf teaching 20 years ago. She serves on the board of the Center for Biography and Social Art (www.biographysocialart.org) and with Kathleen Bowen, Jennifer Brooks-Quinn and Patricia Rubano develops and facilitates workshops for Waldorf schools and ASA branches. She also enjoys creating biography and social art workshops for the general public.

18 • being human

Two Lives in Progress

reviews by Joyce Reilly

Sunshine Girl: An Unexpected Life, by Julianna Margulies; Ballantine Books (2021), 256 pp.

Whenever I hear that a new celebrity biography is out on the shelves, I sigh. Talented as many actors are, and public figures, fascinating, the books are often short accounts of their early life and long accounts of a career gone well. Somehow the inner life—what was going on in that child’s mind, what the early days of a working actor felt like, what all the names being dropped and the prizes and accolades signify on a deeper level—are lost. So, when I heard from my local library director that she had spent a spring Sunday afternoon wrapped up in a hammock and a book, I was intrigued to hear that it was the autobiography of Julianna Margulies. I asked, tentatively—interesting? She replied—fascinating!

For those of us who are not television watchers, this surname may still seem familiar due to her parents involvement with anthroposophy: her mother, Francesca, a eurythmist and teacher for many years here in the US and abroad, and Paul, her father, a dedicated study group leader. Paul is also famous as an advertising executive who made his name for the Alka-Seltzer jingle—“Plop plop fizz fizz, oh what a relief its is!” Few Americans of a certain age are not familiar with those words!

Julianna has had a career on television, stage, and film, but is known mainly for important roles on long-

passing up another stint on ER , for millions of dollars, in order to return to her home in New York and the stage.

The book is indeed fascinating, because it is an honest, deep-going, detailed, and vibrant account of an early life leading up to a successful career and fulfilling family life. Julianna spends the majority of her words describing her early life: born in the anthroposophical community in Spring Valley, NY, taken back and forth to various spots in Great Britain and Europe connected to her mother’s career as a eurythmist and teacher, visiting her father abroad as well. Endless moves, new schools and new partners (her mother) and new jobs (her father),—the impression is a whirlwind that two older sisters escaped earlier and that Julianna endured with grace, anger, and some rebellion. Above all, it’s an honest book. The descriptions of her mother’s wild switches from one unsuitable place or lover to another, her father’s reserved support and continual changes, can be heard with a bit of a cringe. They do not come off as the most sensitive or supportive parents, despite The Study of Man and all the Waldorf exposure and soft dolls and pinecone people. Julianna mentions anthroposophy, as a part of all these moving pieces, as a serious endeavor, if a bit quirky, and definitely not a cult! In doing the round of interview shows (virtually) from Oprah to Symphony Space, the word “anthroposophy” is not often heard, but when it is, there is a respect that comes from what it seems is her understanding of her parents love for

Training

NEW COHORT BEGINS SUMMER 2022 DENVER, COLORADO | June 24– July 15

concentration in Early Childhood (Pre-K to KG) for schools inspired by Waldorf principles • Anthroposophically based • 8 courses over 26 months, 7 semesters • Accredited by D igned for working teach s. LEARN MORE: gradalis.edu Accrediting Council for Continuing Education & Training

summer-fall issue 2021 • 19

Teacher

BEING HUMAN

And this is what makes this autobiography so unique and so moving. Julianna Margulies describes a childhood and adolescence that one would not wish for—lack of stability, having to parent the parents, inappropriately mature expectations, and continual challenging events. Yet Julianna speaks of her parents today in the most loving terms. Her father Paul was surprised by her anger towards him when she began to be independent, and, after some clarification, wrote her the most heartfelt letter of apology for his own missteps and lack of understanding. When Paul crossed the threshold (she didn’t use this term) in 2014, she wrote a beautiful letter of tribute and grief which was publically shared. One can feel for Francesca, hearing the extremely open and candid way that Julianna describes the boyfriends, abrupt moves, inadequate housing, etc. Yet her mother’s reaction to knowing that this book was coming about was, “Go for it!” In the acknowledgements, Julianna paints the picture of sitting on a porch, sipping iced tea with Francesca and laughing over the manuscript, together.

The most important point of this story seems to me to be what Julianna expresses directly: things were tough, not ideal, too fast, sometimes confusing, but she was not abused. The chaos was not abuse—what an extraordinary distinction to be able to make. She always was loved, and knew she was loved, for herself in all her beautiful manifestations. This is the finest tribute to a childhood one can hope for: that the journey was filled with love. The book is dedicated to “My parents, Francesca & Paul Margulies.”

Gardens of Karma: Harvesting Myself Among the Weeds, by Susan West Kurz; White River Press (2021), 296 pp.

By happy coincidence, another autobiography has appeared “on the shelves” by Susan West Kurz, whom many of you may know as the person who introduced the Dr. Hauschka line of skin care products to the United States in such a way that they have become quite well known. Previously concentrated in health and whole food shops, it is now distributed through high-end retailers, special-

ized cosmetic shops like Sephora, and now the internet. The Dr. Hauschka line also inspired estheticians to be trained in the special skin treatments developed by Elizabeth Sigmund and used in clinics and salons in Europe. Elizabeth Sigmund and Dr. Rudolf Hauschka were deeply connected to the work of Rudolf Steiner, and the inspiration for one of the most highly prized cosmetic lines in the world came from their understanding of the human skin as an organ, and their knowledge and respect for the healing properties of the plant world.

Susan begins her tale with a visit to a writers’ workshop that leads her to express her love for Demeter, the goddess of agriculture, and then to tell us about her ideal vacation in Sicily in an area that is known as the womb of Demeter. After a lovely walk through fragrant gardens and appreciation for the sights and smells of the land that is so uniquely captivating in Italy, we are transported back to her childhood, and how the gardens of her aunt and uncle comforted, intrigued, and inspired her from an early age. Woven into the story of her life, from Rhode Island to New York City and back to New England, are encounters with the gardens of friends and relatives, and the deep holding of one’s being that can occur when there is a connection to the land.

After a somewhat painful childhood with a deeply quiet father and a mother with extreme mood swings, and after a usual elementary school and high school experience, Susan’s college years brought her into new social circles. Moving off campus led to a truly karmic meeting, involving a garden, with the actor James T. Walsh. Known then as Jim, and later professionally as J.T. Walsh, Jim introduces Susan first to anthroposophic medicine administered by a Dr. Laskey, then to Heinz of the Meadowbrook Gardens. Jim was also studying anthroposophy, and Susan, by now living with him and expecting a baby, was a serious and eager student of Dr. Steiner.

What follows is an account of a challenging, inspiring, tumultuous life with Jim and baby John, moving from Rhode Island to New York City, becoming more interested in the Dr. Hauschka line and its potential to be unique and highly-valued in the skin care world. Susan took on

20 • being human

training as an esthetician, setting up a salon, and eventually moving away from Jim as he became JT, a well-known presence both on stage and notably on various screens. (Jim’s alcoholism was a factor in so much of the tumult, and it was at the beginning of an attempt to get a healthier and freer life that he died at the age of 55 in 1998.)

Truly on her own, Susan’s business talent became apparent, and with her meeting a biodynamic farmer at a convention, the Hauschka line was born. Susan West and Clifford Kurz became a team in work and in life and were able to make Hauschka a well-known, profitable business. Susan’s account of finding her voice at business meetings and her feet on the ground with yet more gardens and Clifford, gives a special slant to the usual American success story. Susan and Clifford went on to be parents of two adopted children; though we do not get details of their growing lives nor that of John, we may surmise that, while the challenges do not stop, all sounds quite positive now.

This book leaves me asking for more. Who was Dr. Laskey? Also Heinz of Meadowbrook Gardens—there must be an inter esting story there. How did they all met in the small state of Rhode Island! And the salons and studios that Susan and friends established in New York and around the country, do they continue to serve the serious as well as the celebrat ed? And where can I have a Haus chka facial? The descriptions of the products, the fields of flowers and herbs that create them, make me both curious and envious of those who were there to experi ence all of this.

There is a connection be tween these books. When Susan West Kurz was creating the Dr. Hauschka business and needed advice on advertising, Paul Mar gulies was her trusted advisor! Working with Paul, Susan was able to develop the confidence

to trust her own understanding, and to own her voice. That voice was there already, waiting to be heard loud and clear.

These autobiographies of two women with significant relationships to anthroposophy and celebrity make refreshing and compelling reading.

Any season is a fine time to meet The Sunshine Girl and The Gardens of Karma

Joyce Reilly ( joycereilly@aol.com) found the Camphill movement in early adulthood, worked closely with Georg Kühlewind and supported his work in the USA, and has served on the council of Anthroposophy NYC and as president of the Janusz Korczak Association of the USA.

Celebration of the Festivals

Renewal of the Sacraments

Services for Children

Religious Education

Summer Camps

Study Groups

Lectures

The Christian Community is a movement for the renewal of religion, founded in 1922 with the help of Rudolf Steiner. It is centered around the seven sacraments in their renewed form and seeks to open the path to the living, healing presence of Christ in the age of the free individual.

Learn more at www.th e christiancommunity.org

summer-fall issue 2021 • 21

Connect to the Spiritual Rhythms of the Year...

A sacred service. An open esoteric secret: The Act of Consecration of the Human Being.

That humanity is fully interwoven with the living earth, and indeed the solar system and cosmos, is a foundational insight for the anthroposophical initiative in agriculture, nutrition, and planetary healing. Biodynamic agriculture was one of Rudolf Steiner’s last initiatives—all of which were undertaken because individual people has asked for them. The heavy use of

artificial fertilizers after World War I in Germany caused many farmers to realize that the Earth itself was being stripped of its life. Steiner offered the perspective that a farm could be integrated, with the mineral soil, the life of the plants, the consciousness of the animals, and the creative guidance of the human being forming an organism and bringing new life to soil.

Open-Pollinator Future Lab Youth+Agriculture

by Walter Goldstein

A presentation given on Friday night, February 12, 2021, to the Youth Section in North America

There are at least three worsening crises. There is the crisis of climate instability which is coupled with global warming and catastrophic shifts. There is a human health crisis associated with lifestyle shifts, chronic illnesses, mental illnesses, degenerative diseases, and pandemics. And the third crisis has to do with a degeneration of the life forces in the soil, the purity of our water, and the nutritional value of the plants we eat.

These three crises are interlinked and have primarily to do with our needs for individual development and the prevalent immature societal paradigm. We unleash and flock to technologies that promise us greater powers and efficiency. These technologies are exploitive, attractive, lucrative, and convenient, short term. Collectively, we refuse to foresee or ameliorate their longer-term impacts on us, on the Earth, and on future generations. Around these new technologies, capital becomes concentrated in the hands of sanguine investors but money largely rules where the money flows. Many potential actors are locked into institutional machines and their jobs do not allow ethical decisions but rather decisions that perpetuate their institutions and maximize profitability or dominance. Big institutions, whether they are companies or universities or USDA, are increasingly calling the shots in agriculture.

I would like to share with you three discoveries and actions I am involved with that are critical for addressing these crises with healthy agricultural solutions literally from the ground up. These are:

1. partnership breeding,

2. direct observation of the life of the soil, and

3. finding new forms for commercialization and cooperative work.

This work I am going to tell you about is new and incomplete and it needs help from younger people to thrive and grow into the world.

Breeding and seed

The first is breeding and seed. You may know that as the art of breeding dies out in the agricultural community, I and others, including some young people in the organic movement have begun taking back our crops. You may have heard that our food has become progressively less nutrient dense as we implemented chemical farming and bred for yield. You probably know of problems with food allergies and interest in older kinds of crops that may not be allergenic.

You probably are also all familiar with genetic engineering where genetic material is taken from one organism and put into another. This has allowed the predominant use on this continent of genetically engineered corn and soybean crops that tolerate the herbicide Roundup. Roundup has become the most used pesticide on the Earth and is associated with degenerative diseases and widespread pollution.

Aside from that, what you probably don’t know is that breeding is becoming more and more unnatural. In order to speed up the process of breeding, hybridized plants are tricked into forming ‘haploid’ seeds with only the maternal set of chromosomes. Those haploids are grown out and forced to double their chromosomes in order to make a normal plant. Aside from the fact that this is a painful process to watch, we really have no idea of the long term consequences on the plants and on humans. But the process is faster than normal breeding, it lends itself to factory production, the resulting plants are stable and they can be easily patented. Therefore all the

22 • being human

big companies do it. Furthermore, CRISPR gene editing is just around the corner for tailoring the genetics of our plants. The worst is that we will soon not know whether a plant is engineered in this way or not.

Plants have been defined at universities as genetic machinery that should be programmed by clever scientists. Manipulative biotechnologies are looked at as being necessary tools in the face of the climate crisis. As a consequence of this genomic focus, humans are being separated from plants. Breeding has become a laboratorydriven exercise with genomics where people live in front of screens and robots and cameras are assigned the task of making observations. All this happened because the art of human/plant dialogue has not been properly valued and cultivated because it is not seen to be ‘hard’ materialistically based science. Nevertheless, it is what has brought us healthy agriculture in the first place and is the fruitful source for future healthy breeding.

We practice partnership breeding at the Mandaamin Institute. Critical is that the human pays attention to what the plants do in the field. The human is a partner in the breeding process. It is important that we know our role, do a good job with observing, reasoning, choosing environments and the best parents, and making the right crosses and selections. The plant and microbial partners are the biologically creative element. Under our low input, biodynamic conditions, the plants undergo a process which we call emergent evolution. Plants adapt to new environments and stress by throwing out new variation and patterns in tandem with epigenetic shifts and rearrangements of their chromosomes. At the Mandaamin Institute we are harnessing this more respectful approach with corn, the Earth’s most grown cereal crop. New patterns of storage proteins have appeared that increase the nutritional value of our grain tremendously. In our breeding process the plants became more nutrient efficient, partnering with bacteria that help them obtain minerals and nitrogen that make the grain much more nutritionally valuable. They therefore become less dependent on nitrogen fertilizers.

Nitrogen fertilizer is widely used to grow corn, and the nitrate from it leaches down and pollutes our wells and lakes or it is converted into nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas. We are polluting the water and the sky with the way we grow corn nowadays. Making nitrogen fertilizer is incredibly energy intensive. It takes the energy equivalent of 17 gallons of diesel fuel to make the nitrogen fertilizer needed to grow an acre of corn. But our new

corn fixes nitrogen with the help of bacteria from the air and seems to respond negatively to nitrogenous fertilizers.

Soil life

Unfortunately, we don’t know the life that we depend on. And society does not have a language for it and there are taboos that keep us from paying attention. The soil is alive or dead to various degrees and the human being can develop a real relationship to it by actively observing it through the year. The form of the soil, whether it is brick like and massive and hard, or crumbly and alive, reflects the ebb and flow of this life. There is an inner life to the soil and the human being can be an instrument for detecting and speaking for it by meditating in a focused way on what the soil is like. A language will emerge in us as we study it together and develop an objective soul to soil connection.

My experience has been that the life in the soil degenerates through the growing season. The plants appear to live from this soil life in a kind of parasitic way, depleting it. If the soil is fertilized with organic manures, particularly in the fall, there is the chance for a re-enlivening of the soil to occur. Forces from below become particularly active in November transforming the soil again and filling it with high quality life if the soil has been adequately manured in the past. If the soil is filled with that high quality life the crops will have great taste and value for the human.

In that regard, I would like you to join me in research on your own soil and crops. Our protocol is described in detail on the Biodynamic Association website at: www.biodynamics.com/experiencing-life-quality-our-soils . If you are inclined to study the life

of the soil and

the Earth please note: Mike Biltonen and I would like to schedule our first Zoom meeting in March for an introductory session, which should be followed by meetings every month starting then for each Friday of the month. These would be hour long sessions where people would succinctly relate findings and questions. Please contact Mike if you wish to participate at mikebiltonen@gmail.com

New social forms

The seed world is incredibly competitive. Intellectual property issues and profits sync with greater emphasis on patents and commodification of crops. Orphan crops, not profitable enough for the companies, are neglected. There do not exist platforms for cooperative development of crops across institutions and no framework for help-

summer-fall issue 2021 • 23

ing small scale breeders. In that context we are working with the Northern Plains Sustainable Agriculture Society to develop a Quality Crop Association and the Nokomis Gold Seed Company. We hope to form the latter as a perpetual trust that could attract impact investors without the investors being able to change the intentions of the company.

Biography

My life reflects my desire to form myself as a key to resolve the problems that I see. I was born in 1953. Throughout my childhood I had a love for nature. I felt that there was an enormous wisdom in all living things and I wanted to understand it and apply it to resolve the problems that I knew would face humanity and the Earth as time went on. In 1972 I discovered anthroposophy and biodynamic agriculture while trying to find myself in southern California. I was 18 years old. That started me into a process of trying to shape my life so that I could have an impact and be of some help for the coming problems. It led me to working on various organic and biodynamic farms.

In 1976 I completed a bachelor’s degree in botany in Seattle and thereafter left for Europe to do research studies at different biodynamic research centers in Switzerland, England, and Sweden. I had good mentors there in the form of Herbert Koepf and Bo Pettersson who provided a example of agricultural scientists with insight who were living by principles they believed in.

On the way I met my wife, Bente, and was married with her 1980 in Norway. We returned to Washington State to attend the agricultural university where I was able to earn a masters and doctorate in agronomy and to do research on new crop rotations and effects of biodynamic preparations.

In 1986 I joined with others in Wisconsin to start Michael Fields Agricultural Institute and served as research director there for 25 years. In that time my wife and I purchased a 35 acre farm, where we bred sheep, corn, and fruit trees, and raised kids. My wife began farm school programs with Dana Burns and then continued that for over two decades in the form of a small company called “Farmwise.”

In 2011 I left Michael Fields to start a new non-profit organization in Wisconsin called the Mandaamin Institute with the help of friends. There we work on the farms of cooperators and mainly breed corn. We breed for enhanced nutritional value (nutrient density) and for

nitrogen efficiency under low input, biodynamic conditions. At the Institute we develop and practice “partnership breeding.” This entails a different attitude, where we work with corn and its microbial endophytes as partners, to breed corn that the world needs.

We partner with companies and farmers and universities to do research in Wisconsin and neighboring states. We have an extensive network and lead efforts in public breeding of corn for organic farms throughout the country. This year we are rolling out our first commercial releases. Our corn has much higher nutritional density which strongly affects its value as food and feed, and can lead to a reduction in the use of harmful feed additives. Furthermore, we believe that some of our corn fixes nitrogen from the air with the help of microbes. This is very important because it could lead to reduction in the use of nitrogen fertilizers which are polluting water and air and contribute a potent greenhouse gas. Now our corn also produces yields competitively with conventional hybrids on organic farms, but without needing the same chemical inputs.

Part of our dilemma now relates to how to commercialize what we have and to work with other breeders according to the principles we believe in. We seek to provide an alternative to the normal venture capital route by building an association with others in order to protect our core set of values. Our target is forming business forms such as a perpetual trust, to give the right form to relationships. Engagement with the Northern Plains Sustainable Agriculture Society (Verna Kragnes) and with the Foundation Organic Seed Company are important parts of how we inch forward. Finding funds to do our work is a perpetual challenge, engaging me in fund raising for federal grants and foundation grants for at least a quarter of my time. We are by no means well off, but somehow, we manage to be opening up the door to a new future.

Another dilemma is how to grow the right people to take this effort into the future. I am getting older and cannot keep up the physical work. I do have some good technicians and farm help, but we need to find people who can grow the inner side and management work in a leading way.

Clearly, people who can take on such a venture do not grow on trees but have it in their hearts and it must be cultivated, even in the face of financial uncertainty. If you are interested in our work and helping to foster it in some way, feel free to email me at wgoldstein@mandaamin.org and to visit our website: www.mandaamin.org

24 • being human

Health is a topic both intimate and limitless. Its field is truly suggestive in scope of the whole universe turned inside out. The majestic qualities of minerals are liberated in organic fluidity, the tiny cells of life are incalculably busy, the sensitivity of active and reactive consciousness amazes, and all is touched by the slowly unfolding creative potential of individuality.

The centenary of anthroposophic medicine in 2020 came in the midst of a global health crisis. That jolt demands us to see ourselves more truly in this human existence on a living earth. We begin with an account some fifty years old, followed by excepts from a new paper. The language change of half a century already reveals tremendous challenge and change.

“The young doctors sought not merely a deepened knowledge, but inwardly developed powers which could give depth and renewed life to the whole art of doctoring. To the stammering questions they brought to Dr. Steiner, he gave answers which can be summed up in the words: “You are seeking to make medicine more human.” ... In an age when even in medicine the materialistic world-outlook has more and more to say, and human perception threatens to be destroyed by technical and mechanical diagnosis, Rudolf Steiner with Ita Wegman laid down the first principles of the renewal of a medicine that has its starting-point entirely in the knowledge of the human being. This knowledge does not take into consideration only our bodily sheaths that may become sick, but also, what the eternal in us wishes to experience, has to experience, in an illness. With the knowledge of reincarnation and karma as background, the conception of sickness and healing given us by Rudolf Steiner can be ever further developed.” Grete Kirchner-Bockholt: (Golden Blade 1958, “Widening the Art of Healing”)

Rudolf Steiner & the Art of Healing

by Christoph Linder, MD

We reprint this essay from the first issue of The Journal for Anthroposophy, Spring 1965, for its clear and direct statement of the basis of anthroposophic medicine (AM), which Dr. Linder brought to the United States. The medical and social changes of 56 years are also of interest. Dated references to then-current activities have been deleted, and gender signifiers (man, he, his, him) that were considered neutral in 1965 are updated.

The scientist of today generally does not like to speak of the spiritual, though they may feel very clearly that there is a realm of dynamic creative forces in nature that cannot be measured and that cannot be perceived by the ordinary senses. They consider the spiritual as belonging to the department of philosophy, pure psychology, or religion. The question arises whether it is possible to raise the knowledge of a spiritual world above mysticism and feeling to the level of conscious and concrete perception.

If the answer is no, all the teachings of spiritual science are meaningless. If it is yes —and Rudolf Steiner’s answer is a clear yes —then the greatest vista opens up for medical science, namely a knowledge of body, soul and spirit, and how they interpenetrate each other, that goes far beyond any attempts of modern science and psychology.

The student will find that nothing in this knowledge of the supersensible is in contradiction to medical science of today. True, interpretations of established facts may differ, but it is equally true that such spiritual science

would be pointless without close association with modern science. As a medical practitioner of many years, I can say that modern research becomes infinitely more interesting when seen in this light.