11 minute read

Where on Earth Is Heaven? by Jonathan Stedall

Hawthorn Press, 2009, 566 pgs

Editor’s Note: by separate routes we received two reviews of this unusual book. Since they are relatively short and different in character, we are publishing both. The second review, below, is by Signe Schaefer.

Review by Frederick J. Dennehy

Books describing an author’s spiritual journey generally tend toward an ending. Readers find themselves traveling along with the author and sense in the final pages that a “destination” of some sort will be reached.

Where on Earth Is Heaven? is not structured in that way. As Richard Tarnas aptly notes in his foreword, Jonathan Stedall’s book is more like a fireside chat. His account has the freshness and honesty of a friend’s impressionistic reminiscences, as well as the meandering and somewhat repetitious features of informal conversation.

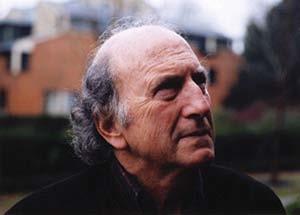

Mr. Stedall’s original intention was to write very little about himself, and to focus on the people whom he had come to know and the ideas he had encountered that had influenced him spiritually. Readers of the first draft suggested that the book needed to be more autobiographical; consequently, Mr. Stedall, with some reluctance, extended his account to include moments from his “own bumpy journey—the downs as well as the ups.”

“Where on Earth is heaven?” was a question originally asked many years ago by the author’s then seven-year-old son. This book is Mr. Stedall’s effort, after a gap of twenty years and his encounter with serious illness, to answer it. Each of the thirtysix chapters is connected—directly or indirectly—to the possibility and meaning of immortality. The chapters loosely follow Mr. Stedall’s career as a BBC documentary film producer. His employer (hard to imagine this now!) allowed him to travel—geographically and spiritually—almost wherever his most burning questions dictated.

Mr. Stedall is not a scholar but a producer of films. He is not a man of personal visionary experience but a person of natural devotion and highly focused attention. In the words of Nicolas Malebranche, “attention is the natural prayer we make to inner truth in order that it may be revealed in us.”

This book takes its place on one side of a cultural divide whose fault lines have been visible for a long time and have been widening at an ever-increasing speed. The topography of that divide has also altered appreciably since it was delineated by C.P. Snow in The Two Cultures in 1961. The split is not so much between the scientific method and the humanities (Geisteswissenschaft), and it would be crude to maintain that it is simply between science and religion. Rather, the division is between those persons who sense and seek an intrinsic meaning and purpose in the world, and two other groups: those who see any notions of meaning and purpose as the ephemeral projections of needy humans, determined by a combination of biochemistry and “contingency”; and those who believe in the existence of objective purpose and meaning but think that these are destined to be realized elsewhere, in a “heaven” somewhere beyond Earth. That “somewhere” is often conceived to be on a “thinner” or disembodied plane that is subject nonetheless to “ordinary consciousness”—the same consciousness that regulates our experiences at ten in the morning on a not very exciting workday.

Mr. Stedall takes his stand unmistakably on the first side of this divide, but not as a combatant, a philosopher, or a systematizer. Instead, he reports to us as an observer of long standing who has seen and inquired into a vast range of human experience. A significant part of that experience is closely related to anthroposophy.

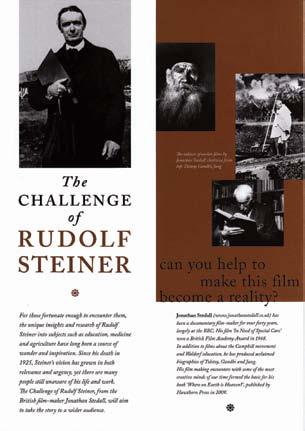

Mr. Stedall returns again and again to Rudolf Steiner, as a philosopher, an esotericist, and the source for the creation of Camphill therapeutic initiatives and Waldorf education. Very little in these pages could be deemed to be “original” regarding Steiner, and a fair portion of the commentary is overtly mediated through secondary sources. Mr. Stedall was enormously impressed with the Camphill movement, which he encountered through his work documenting the Camphill community, Botton Village, and the school at Camphill Aberdeen. He was strongly influenced by his nine-month stay at Emerson College in England, particularly by the scientific method of founder and principal Francis Edmunds. During that same stay he boycotted all eurythmy classes. While he enrolled both his children in a Waldorf school, he found the experience there insufficiently flexible to accommodate the particular interests evinced by his children when they did not conform to the time frame expected by the teachers concerned.

But this is not a book for students of Rudolf Steiner or for participants in the daughter movements of anthroposophy who want to go deeper. Nor is it a book in which you will find the struggles and hurdles encountered by a man who at long last “finds” anthroposophy. What you will find is an intelligent, intensely curious, and candid thinker who experiences and digests the insights of Rudolf Steiner along with those of Carl Jung, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and many others, albeit with a partiality toward Steiner. You will find a man fascinated by the human side of great thinkers and doers. And so he places Steiner in both surprising and unsurprising company, along with Tolstoy, Gandhi, Sir Bernard Lovell, Malcolm Muggeridge, the poet John Betjeman, Laurens van der Post, and many others, including anthroposophists like Edmunds, John Davy, Owen Barfield, Karl Koenig, James Dyson, and Rudolf Meyer. Mr. Stedall is nothing if not eclectic—he takes his wisdom, purpose, and meaning where he finds them. And after his long journey, he refuses to “fall into the trap of suddenly trying to make everything comprehensible.”

But Mr. Stedall’s journey has not been without order and progress. In his conclusion, he is firm and confident in his dismissal of militant atheists and acolytes of the random such as Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens. He believes that there are no limits to knowledge—one horizon always follows the next. As for the question that engendered the book— “Where on Earth is heaven?”—the answer is clear to him. Heaven is a possibility that can become a reality, not as some “thing in itself” only derivatively knowable, but here on Earth, “amidst all the obstacles through which we learn and grow.”

Where on Earth is Heaven?

Review by Signe Schaefer

Jonathan Stedall’s Where on Earth is Heaven? is a big book—in size and even more in the breadth of its imagination. I hope no one will be put off by its length; for from the opening of its title question, asked many years ago by the author’s young son, the reader is invited on an extraordinary journey through the 20th century and beyond. This is a cultural and spiritual journey, accompanying a man finding himself through following his questions and honoring what he calls the “awakeners” along his way. The details of the author’s life are never the point of his writing; this is more an inner memoir, a record of the legacy he has received from literature, art, psychology, natural science, philosophy, anthroposophy, and most of all from other people. It is the story of a life lived deeply and caringly; and its telling is, in a way, a call to us all.

For me that call felt quite personal, an invitation from a friend to consider with him the searching and the influences, the questions and the gratitudes of a lifetime. I have known Jonathan since the Spring Valley International Youth Conference in 1970, and I had the good fortune to see him often when my family lived in England through most of the 1970’s. His keen intelligence, his warm heart, and his ever-ready wit permeate this rich book.

Throughout his long career as a documentary filmmaker Jonathan had the opportunity to interview many remarkable individualities of our times: the writer Laurens van der Post, poets John Betjeman and Ben Okri, novelist Alexander Solzenhitsyn, physicist Fritjof Capra, and economist E.F. Schumacher to name a few. During his many years with the BBC, he also directed films on Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, and Carl Gustav Jung. Now he brings these people, and many others, into his book, inviting us along on his different projects and introducing us to those he felt privileged to come to know. With deep respect he explores the varieties of thought and creativity that have shaped our modern consciousness. But Jonathan’s wide interest is not limited to the famous and influential. He also shares stories of the wounded and vulnerable, and of everyday people doing quiet, often unnoticed good work.

Since his youth Jonathan kept a notebook in which he jotted down questions or insights that occurred to him, quotations from his reading or poems that moved him. The book is rich with these mementos of his meandering intellect and heart. At times it feels almost like an anthology of treasured references. Again and again we meet the writers who played a significant role in his inner journey, thinkers like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, C.G. Jung, and Rudolf Steiner. We follow the evolution of his thinking as it is challenged and inspired, as his life experiences evoke ever deeper questions about life and death, and as his searching takes him around the world and also approaches invisible realms.

Rudolf Steiner plays a central role in Jonathan’s quest and in the book. We meet Steiner the man, his teachings, and the results of his spiritual research. In clear and approachable language Jonathan presents complex ideas such as the four-fold human being, reincarnation and karma, life phases, the Christ being, the evolution of consciousness, and Waldorf education, to name only some of the areas he addresses. He has had his arguments with Steiner which he expresses, but also allows to evolve over the years. His quest is ongoing, and his gratitude is enormous. He is deeply motivated by a certainty that people today need to meet real ideas and real pictures of what it means to be a human being. Committed as he is to speaking the language of everyday and avoiding exclusive terminology of any kind, it must also be said that he is an elegant and inspiring writer.

Early in his career Jonathan met the work of the Camphill movement, and the profound effect of his meetings with both co-workers and villagers is movingly invoked in the book. In 1968 his film In Need of Special Care won a British Film Academy Award. This was followed over the years by other films about Camphill and also about Waldorf education. It is exciting news that he is now preparing to film The Challenge of Rudolf Steiner. His experience documenting other great world leaders and his lifelong work with anthroposophy make him singularly qualified to direct this film, and we can await it with great anticipation.

As a closing to this review, I would like to mention that my husband and I read Where on Earth is Heaven? aloud, over the course of many weeks. We looked forward to this part of our evening when we would open that big book and enter into this story of our times. Inevitably our reading would spark rich conversations and reflections about our own lives. If you like to read with others—one or a group—this book is a great choice. It seems somehow appropriate to share it with others, because in a way the book itself is a testament to the importance of relationships and to the enduring reality of what lives between people, even beyond death. It is all about making connections—with others, with ideas, with history and the times we live in, with nature, and with the spirit. Finally, whether one reads it with others or alone, this is a book that will nourish and inspire.

Signe Schaefer was for many years Director of Foundation Studies at Sunbridge College. She founded and continues to direct a part-time program in Biography and Social Art. She has had a life-long interest in questions of human development.