4 minute read

JOSEPH SCOTCHIE

jscotchie@antonmediagroup.com

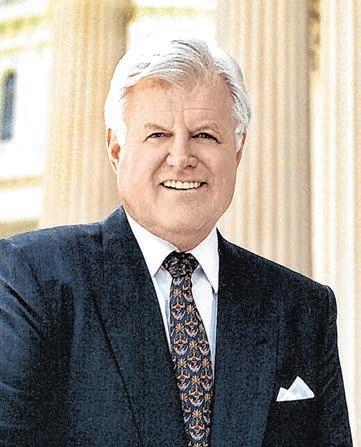

“We’re living in Ted Kennedy’s America.” That witticism was offered by Joe Sobran in the wake of the 1987 defeat of Robert Bork to the Supreme Court. Senator Edward Kennedy (D---MASS) led the charge, declaring in a demagogic tirade that in “Robert Bork’s America,” women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks regulated to the back of the bus, school children denied the teachings of evolution, and “rogue police” breaking down anyone’s doors.

Advertisement

A qualified and articulate jurist, Bork never deserved the demagoguery slung his way. The man, however, had little support from the Ronald Reagan White House. Bork was defeated and liberals dominated the court for the next three decades.

Ted Kennedy’s America? Who can doubt it? In the early 2000s, Kennedy took on same sex marriage as a fighting cause. Conservatives snickered at this crazy old man. Who’s laughing now? The same Wall Street Journal, National Review, commentary-style conservatism that once opposed and ridiculed the gay rights agenda now supports Kennedy’s views on marriage.

John A. Farrell’s biography is the first full-length treatment of Kennedy since his death in 2009. It can be a tortured read on a tortured life. Not hagiography, the volume still ends in triumph. A Life is for those fans of Camelot who wish to relieve the Kennedy saga in all its tragedy and glory.

Ted Kennedy was born to the breed. His father, Joseph Sr., a wealthy banker, had wanted to make the leap into politics. The man lived for power. However, his tenure as U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain, where he bitterly opposed America’s entry into World War II, sank any hopes. The torch was passed to Joe Junior, who also had a taste for politics. Muscular and confident, Joe Junior could never comb gray hair. He died in action during the war.

It was now onto Jack, Bobby, and Ted. In 1960, the youngest Kennedy worked as a West Coast coordinator for JFK’s winning presidential campaign. He dreamed of a life in Arizona, far from the political world. That could never happen. The 1962 Massachusetts senate race beckoned. After Nov. 22, 1963 and June 6, 1968, Ted Kennedy’s own presidential run was an inevitability. It was as if destiny was out of his hands. When that 1980 challenge to President Jimmy Carter failed, Kennedy returned to the senate, where he had found a home. political moments stand out. Farrell cites Kennedy’s floor leadership on the 1965 immigration bill. That bill, long a goal of President Kennedy, probably would have passed anyway. In truth, it was the president’s assassination that revived the bill. Still, the younger Kennedy’s hand was on the most significant legislation in American history.

Most of the book is a rendering of Kennedy’s many initiatives and triumphs: Proposing an opening to mainland China, cancer research, health care (where he worked with President Richard Nixon), AIDS research, liberal immigration, the vote for 18-year olds, the defeat not only of Bork, but earlier of both Clement Haynsworth and Harold Carswell to the Supreme Court, the nuclear freeze movement and oddly, acting as a courier for messages from the Reagan White House to the Mikhail Gorbachev Kremlin. It was to Kennedy that Gorbachev revealed his intention to withdraw from Afghanistan.

There is Kennedy the man. After the assassinations of his two older brothers, the burden of an entire family was on his shoulders. He carried that load for the next 40 years. On one weekend in December 1973, Kennedy had to tell his eldest son, Edward Jr., that a cancer would require the amputation of the young man’s right leg. That same day, he rushed off to a local Catholic church to usher Kathleen Kennedy, RFK’s eldest daughter, down the altar in matrimony.

Ted Kennedy’s own presidential run was an inevitability. It was as if destiny was out of his hands. When that 1980 challenge to President Jimmy Carter failed, Kennedy returned to the senate, where he had found a home.

Then there is Mary Jo Kopechne. On the night of July 18, 1969, Kennedy, while driving the young woman home from a reunion party of RFK staff members, hit the small Dyke Bridge in Chappaquiddick, MA, traveling, at some estimates, at up to 20 MPH. Too fast. He did dive into the water time and time again, trying to save Kopechne. Was it possible? Did he act soon enough? The controversy dogged the man for decades. It destroyed his presidential hopes, but not his political career. After 1968, Massachusetts badly needed a Kennedy in statewide office.

The author ends with the eventual triumph of Obamacare, a capstone on the senator’s career. To me, two drive the Irish out of the public schools and out of Boston all together.

In 1965, it wasn’t yet clear that the Democrats would lose their grip on white working-class voters. In time, they did. Kennedy knew the 1965 bill would mean the end of European immigration, including his fellow Irish, into the U.S. No matter. The loss of the white working class has been made up for by millions of new Democratic Party voters from the ranks of Asian and Latino immigrants. President Lyndon Johnson was not the only pol to claim, wrongly, that the bill would not change the population makeup of the U.S. Kennedy made similar remarks. Who cares? It assisted the liberal cause in monumental ways. Farrell, however, gives only a few paragraphs to the 1980 immigration bill, one that expanded family reunification and increased legal immigration exponentially. During the 1980s and beyond, America has experienced the greatest demographic upheaval in modern history. Here, Farrell is not optimistic over the consequences. The other issue is the 1974 Boston busing crisis---a real American carnage. In 1970, Kennedy was under heat from the Kopechne tragedy. That year, during a re-election campaign, Irish South Boston stood with the man. Kennedy appreciated that tremendously.

In the early 1960s, Kennedy supported civil rights, but opposed school busing. In the fall of 1974, the bill came due. Black students from Roxbury, under court order, were bused to South Boston. Kennedy spoke at high schools in both Roxbury and South Boston, then made a beeline to Washington. He was sitting in his senate office when the school buses rolled.

“What can I do?” Kennedy, now busing proponent, asked. How about standing in the South Boston High School front entrance? Kennedy could have rented an apartment in Southie and enrolled his three children in the local public schools now being forcibly integrated, rather than sending them to a northern Virginia private academy.

This is more important than economics. In 1970, Irish Boston stood with their wayward son. Four years later, Kennedy sold his own people down the river. South Boston High School, once the pride of the Irish working-class, no longer exists. And we’re still living in Ted Kennedy’s America.

September 1974 represented the revenge of that city’s Anglo-Saxon elite. For decades, they smarted under Irish rule. By using the black population up from the South, their fellow co-religionists at least, for busing purposes the WASP could now busing

Irish