Acknowledgement of Country

Peppercorn would like to acknowledge the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people as the traditional owners of the land upon which our publications are written and distributed. We would also like to acknowledge our neighbours; the Gundungurra people to our north, the Ngarigo people to our south, the Yuin people on the south coast and the Wiradjuri people of greater inland New South Wales. We acknowledge their elders – past, present, and future – and the elders and first peoples from all nations across the continent.

This was and always will be Aboriginal Land and we recognise that sovereignty was never ceded.

Statement on Historical Wrongs

Peppercorn also recognises the historical wrongs perpetrated against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Peppercorn acknowledges that colonisation is ongoing and racist structures continue to perpetuate the power imbalance inherent within this nation’s cultural, economic, and political institutions. Policies such as the Stolen Generations are not historical, but rather sustained oppression, paternalism and cruelty seen in the continued removal of Indigenous children from their homes per year.

As the ANU LSS’ publication, we cannot ignore the role that our legal system plays in entrenching systematic failures and injustices to Indigenous peoples. Namely, by incarcerating Indigenous Australians at the highest rate in the world and the continued separation of families and communities, the system in which we live and work is continuing a colonial genocide. As law students, we must all undertake to change the racist operation of our legal system and the views within it.

Until an Indigenous voice to speak on their affairs and Country is heard; until there is a treaty; until truth is told and the historical and ongoing pain of those whose land on which we profit from is recognised – there is no justice in our Country.

3 |

“My star sign is Gen-Z with a Milennial Rising”

Aisha Collins Magazine Director

“ It’s the constitution, its Mabo, it’s justice, it’s law, it’s the vibe and ahh, no that’s it, it’s the vibe. I rest my case

- Denis Denuto (The Castle)”

Ella McGrath Art Director

“Get a grip; people hate sissies. No one’s ever going to shag you if you cry all the time - Karen (Love Actually)”

Callum Florance Editor in Chief

Maximus Sandler Secretary

Callum Florance Editor in Chief

Maximus Sandler Secretary

“Let them hate. Just make sure they spell your name right. - Harvey Specter, (Suits).”

Lara Mckirdy Content Editor, Reporting Director

“breaking news…this week I broke my toe on a bed draw in my on campus dorm room. Stay tuned for my extensive investigation into why on campus rooms are unliveable and dangerous environments.”

“Do you think she woke up one morning and said ‘I think I’ll go to law school today’? - Professor Callahan (Legally Blonde)”

Adhina Jose Content Editor

Mel Megale Content Editor

Adhina Jose Content Editor

Mel Megale Content Editor

Letter from the editor

Historical Wrongs

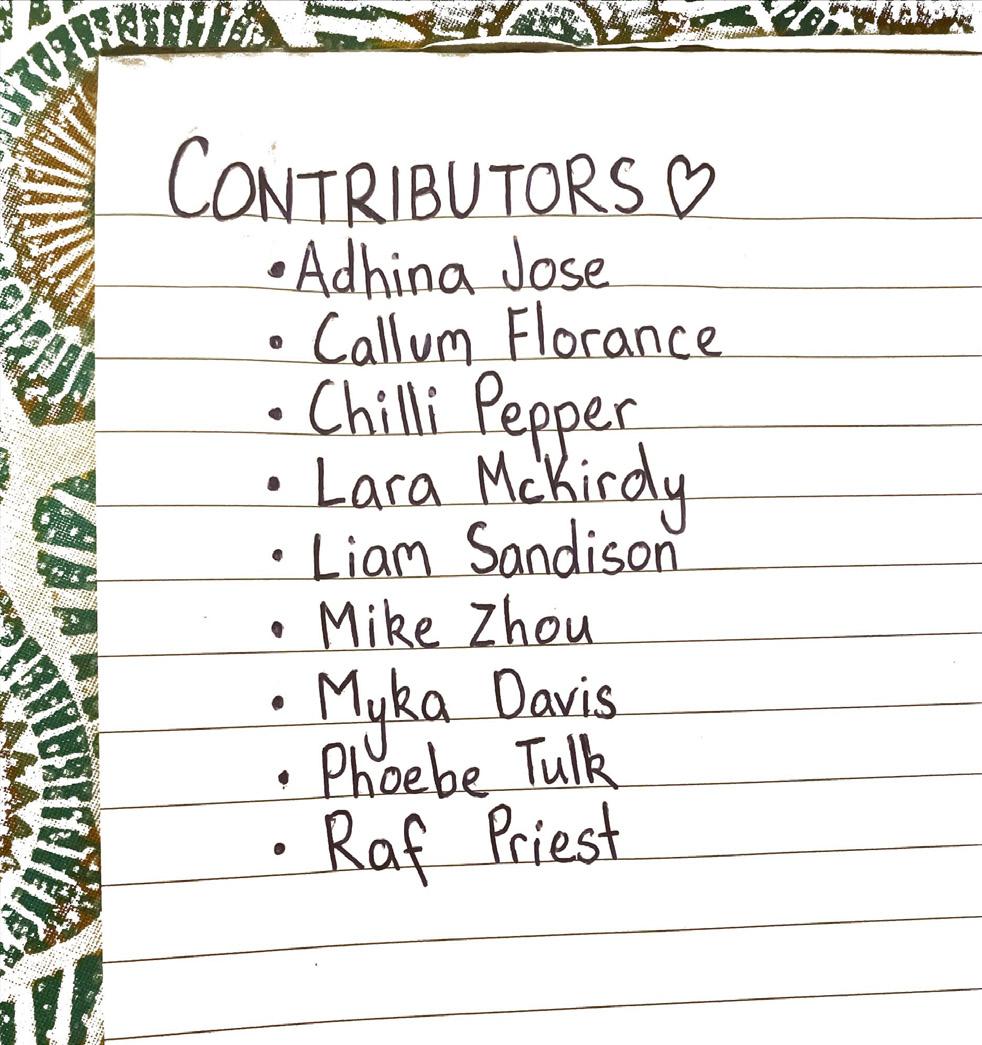

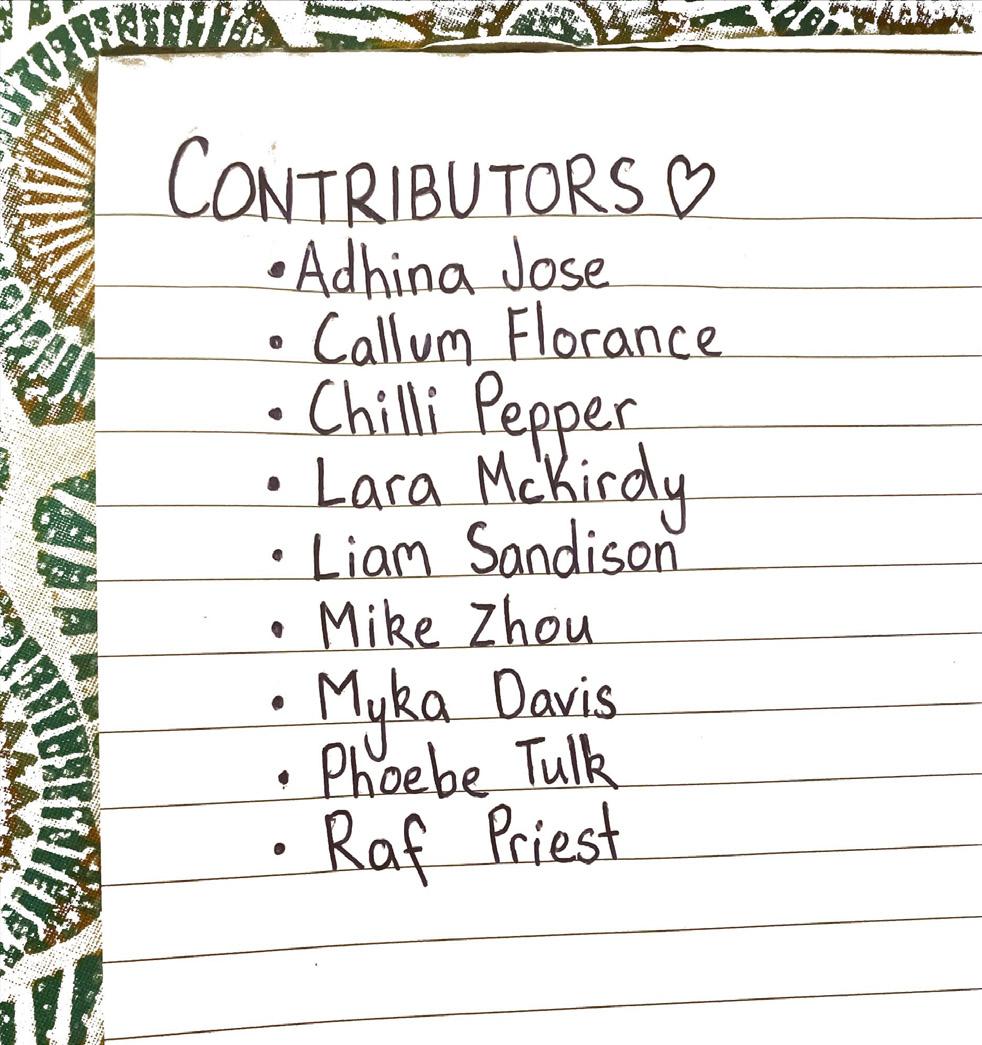

2 - Team and Contributors

4- Letter from the Editor

5 - President’s Welcome

6 - Contents

8. COMMUNITY

9. Pepper Grinder – Online or sit-down law exams for 2023?

● Callum Florance

12. Go get it in Jakarta – Your guide to doing a short course in Indonesia

● Mike Zhou

14. Pepper Grinder – Our year to confront the justice system

● Lara McKirdy

16. In Law – Interview with Scott Phillips

● Callum Florancew

20. Pepper Spray – Another day another SAltled protest

● Lara McKirdy

22. Peppermint – ANU Law Revue

● Callum Florance

25.

CREATIVE

26 Chilli Pepper – Spicy solutions to student problems

● Chilli Pepper

28. Great expectations – Dreams of a law student

● Adhina Jose

30. Laugh, Pronounced ‘Law’ – Third Edition

● Chilli Pepper

32. Pepperoni Observational News Corp

- First Edition

● Chilli Pepper

35. POLITICS AND OPINION

36. It’s Time, To Get It Right – An open letter to our learned political hacks

● Raf Priest

38. An Inconvenient Truth... Again?

● Adhina Jose

42. A Voice for the Voiceless – Review of ‘Broken: Children, Parents and Family Courts’

● Lara McKirdy

44. Bishop & Schmidt by Balenciaga –Where AI and memes meet

● Callum Florance

46. ACADEMIC

47. Incoherence and Indeterminacy - The Impact of Family Violence in Property Disputes (Social Justice Essay Competition 2023 First-Place Winner)

● Phoebe Tulk

54. Deifying the Dirtbag – Why we love to watch terrible lawyers

● Liam Sandison

57. Ours to Lose and Never Regain – The erosion of human rights in the face of Australia’s exceptional counter-terrorism measures

● Myka Davis

Art by Rose Dixon-Campbell

Art by Rose Dixon-Campbell

COMMUNITY

Art by Ella Mcgrath

Art by Ella Mcgrath

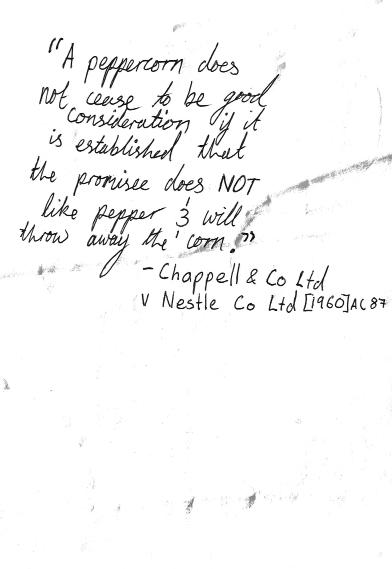

Pepper Grinder:

Online or Sit-Down Law Exams for 2023?

By Callum Florance

Pepper Grinder is a Peppercorn series providing news and reporting relevant to ANU law students via Peppercorn’s Facebook Page and biannual magazine. If you have any interesting stories that you want to share with the ANU Law Community, get in touch!

The COVID-19 pandemic has proved to educators and workplaces alike that more and more of our working existence will happen online. Considering that we live in an online and technologically advanced world, is the ANU College of Law (CoL) really going to shift exams away from the online, take-home model? Is the stomach-churning, anxiety-inducing, anachronistic pen and paper exam model making a comeback for 2023? Here at Peppercorn, we have brought out the Pepper Grinder to update you on whether JD and LLB students will have online exams for 2023.

TLDR: In September 2022, the ANU CoL were waiting to confirm its examination delivery modes from the university executives for 2023 and will notify students once it has made a decision. As of February 2023, this position has not changed.

In-person teaching and learning is back

On 20 July 2022, the ANU College of Law (CoL) emailed law students that it was shifting away from a preference for hybrid (pre-recorded and live online as well as in-person) teaching and learning for 2023. The hybrid format initially came about as a response to the uncertainty created by the COVID-19 pandemic, with convenors effectively using the in-built flexibility of a hybrid model to transition between online and in-person teaching and learning modes whenever circumstances required. This has now changed. The CoL’s preference is now clearly set on in-person teaching and learning for 2023. For LLB students, this shift already became apparent in Semester 2, 2022.

Live online teaching and learning modes were no longer available for LLB students, with some pre-recorded online options still included. In the July 2022 email, LLB students who expected to study online for their degree were told that ‘it would be best to explore online delivery options at other institutions’. For JD students, this shift from ‘all remote learning options for compulsory courses will conclude... at the end of 2022’. Electives may still have an online option, but some electives may ‘be delivered on campus only’. The email summarised: ‘[a]s per university policy, all lectures and some content in elective courses will continue to be recorded; however, the program will no longer have live online options available for any course’. Juris Doctor Online (JDO) students were provided with the same advice as LLB students, noting that ‘it would be best’ for students wanting to study online ‘to explore online delivery options at other institutions’.

How are exams impacted by a shift to in-person teaching and learning?

We have heard anecdotal arguments about student experience being impacted by studying online, with the on-campus experience being heralded as the epitome of a so-called ‘proper’ university experience (i.e., a Group of Eight university experience). That probably makes sense for high school students who finished school online and are wanting more from their education, including making friends and experiences on-campus. In this case, in-person teaching and learning may be the preferred approach for undergraduate students (at least for those whose parents can afford to put them up at a residential college, which shows

a clear preference/incentive for a certain student demographic) .But what about in-person exams? Those same wistful anecdotes fail to include the sheer misery tearful students remembering to bring everything into the exam hall except a pencil, taking sips from clear and label-less drink bottles as their mind empties. I am not sure this belongs in the epitome of a so-called ‘proper’ university experience, mainly just the pity of it.

Take-home exams give students the opportunity to find and establish a calming space to conduct their exam in, the room that works for them in their shared house, their family’s house, or elsewhere. For those who need additional support or a private room, the university should always cater to their needs and provide that support and space.

If the point is to cosplay working as a lawyer, then engaging in legal analysis under pressure on your computer is at least somewhat closer than sitting in a stuffy exam hall with a pencil and paper writing at 50 (big and incomprehensible) words per page. Also, the phrase ‘open book exam’ does not quite fit the bill if you can hardly keep more than one book open on the examination desk.

Conclusion?

Overall, the return to in-person teaching and learning should not also mean a return to in-person exams. For decision-makers, please preference reality over any anachronistic reminiscing on (pre-COVID) ideals of the so-called ‘proper’ university experience. Is the big takeaway from COVID-19 that students are crying out for an on-campus experience that includes in-person exams? Does preferencing on-campus over online teaching and learning also show a bias towards a certain demographic of students in the upper SES band who can afford to relocate interstate? In this case, maybe the pen is less mightier and equitable than the keyboard.

Response from the ANU College of Law on in-person exams for 2023:

In writing this article, the ANU CoL was contacted for a position. I will include the questions and responses below:

September 2022: I understand ANU law students will be expected to move comprehensively from online to in-person from 2023. Is the ANU College of Law intend ing to move all final examinations from online (takehome) to in-person (sit-down) from this same period? Or is the mandatory shift from online to in-person limited to modes of learning via lectures, seminars and tutorials, rather than other course aspects like examinations?

• For Semester Two, 2022 all examinations for the ANU College of Law will remain online. In regards to examination modes for mid semester and final examinations for 2023, this is a decision that will be made by the executive of the university and as soon as we have clarity, our student cohorts will be advised.

• The LLB and JD programs will be delivered on campus from Semester One, 2023, noting that the LLB largely returned to on campus learning during the second half of 2022. There are a small number of LLB elective courses that will remain online again for 2023 due to Convenor location. As per university policy, all lectures and some content in elective courses will continue to be recorded; however, the program will no longer have live online options available for most courses.

• Pos tgraduate online elective course options for JD students will remain available in 2023, however, some elective courses will be delivered on campus only. As per university policy, all lectures and some content in elective courses will continue to be recorded; however, the program will no longer have live online options available for any course. Of note, 2023 is also the final year of the JD Online teachout.

LAWS6244 Litigation and Dispute Management will have the final option of online delivery in Semester One, 2023 with LAWS6205 and LAWS6207 having an online option for the final time in Semester Two, 2023.

• Our postgraduate programs will continue to have online learning options in place for 2023. There will be both on campus and online options available; however, please note that some courses will only be available on campus and some will only be offered online. It is recommended to check our ANU College of Law Course Search to confirm the study mode.

September 2022: What are the policy reasons for why the ANU College of Law is shifting towards mandatory in-person learning (and/or examinations as well)?

• The ANU College of Law has returned the LLB and JD programs back to largely on campus delivery to ensure alignment with the universities preference for the on-campus experience. Both the Vice Chancellor and the university Senior Executive Group are committed to providing students with an exceptional on campus experience and the ANU College of Law fully supports in person delivery for both the LLB and JD programs.

Update from ANU College of Law in February 2023:

• [This is] all still current information as no decision on examinations has been made as yet. As soon as we have clarity, examination delivery mode[s] will be communicated to our students.

Go get it in Jakarta: Your guide to doing a short course in Indonesia

B y Mike Zhou

Jakarta. It’s wet season. Someone is down with typhoid. A taxi from the airport to the city took just over four hours. A city that lacks footpaths, and in fact is quite literally sinking by 4.9 cm per year. Are you sold?

If so, that was easy. If not, I’m going to try to twist your arm.

Mie goreng – yes the ones you eat as a midnight snack. Heard of it? That’s Indonesian.

The country of Bali . Heard of it? That’s actually a province in Indonesia.

Bintang – yes the beer. Heard of it? Guess what, that’s also Indonesian.

Over the summer of 2023, I was lucky to be able to go to Jakarta, Indonesia to do a six-week short course with the Australian Consortium for ‘In-Country’ Indonesian Studies (ACICIS). The program consisted of two weeks of intensive seminars and language classes, followed by four weeks of placement at a host organisation. The course was a lot of fun and an amazing opportunity to gain practical legal experience abroad, as well as learning about Indonesian culture and language. But how was Jakarta?

Jakarta is a wild city. With a population of over ten million people, it’s truly a city that never sleeps and one that epitomises the hustle and bustle of a metropolis. It’s a city with a mix of historic cultures, one that has developed and modernised. When you visit Jakarta, you can definitely see the remnants and parts of the colonial Dutch that has been maintained. While at the same time, Jakarta is a modern city – with skyscrapers everywhere you look. As Alicia Keys sums up New York in Empire State of Mind, the same can be said about Jakarta – it’s a “concrete jungle where dreams are made of”.

Dreams are made in Jakarta, as the food is to die for. Not only does the food slap, but it’s so damn cheap. I could get breakfast, lunch and dinner for under $10 a day. Whether you are vegetarian or love your meats, there are plethora of food options available to you.

Art by Ella Mcgrath

Whether it be satay, rendang, nasi goreng (or nasi goreng tapi tidak pakai daging – for vegetarians), gado-gado, Jakarta is a genuine food heaven – one where I implore everyone to go try it out. I know travelling and doing a short course overseas can be expensive. However, there are a range of different avenues for financial assistance to help you. Whether it be through the New Colombo Plan Mobility Grant, which is available to Australian citizens, or though obtaining an OS-HELP loan, there are various ways to help you get around Indonesia and live your absolute best life.

If I’ve twisted your arm and if you’re interested in visiting Indonesia through a short course, here are my top three tips:

1. Try something different

Whether it be trying different foods or participating in traditional activities (like making batik), I’d urge you to embrace the culture. It’s a culture that truly is unique, and one that’s hard to find back in Canberra. Take a step outside your comfort zone and embrace it.

2. Don’t be scared

It can be a nerve-racking experience going to a foreign country by yourself – I’d be lying to say if I didn’t have butterflies in my stomach. However, what you’ll find is that everyone you meet are so extremely friendly. Whether it be the locals or the other students doing the short course with you, everyone is so approachable and you can definitely make new life-long friends.

3. Value “me-time”

It’s so easy to get caught up in the madness of Indonesia. It’s so important to take care of yourself and to ensure that you do “put yourself first”. Jakarta can be extremely humid and if you don’t look after yourself, you can crash really fast. Make sure you put some time aside for yourself – self-care is integral.

I think it’s time for you to go enjoy your new favourite Indonesian meal with an es teh manis (iced tea) or a nice cold Bintang beer.

Pepper Grinder:

Our year to confront the justice system

In Conversation: Improving the Treatment of Sexual Assault Survivors in the ACT

By Lara McKirdy

Pepper Grinder is a Peppercorn series providing news and reporting relevant to ANU law students via Peppercorn’s Facebook Page and biannual Magazine.

CW: Sexual assault, violence, trauma.

On 6 March 2023, I attended In conversation: improving the treatment of sexual assault survivors in the ACT 1 which, after two years of attending ANU CoL events, was held in a room of maskless attendees. This was one of the first events by the ANU College of Law (CoL) that saw a return to normal since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a sense of normalcy in being present in a room of real, tangible people and not some cold, online meeting room of black screens. The female-majority audience conveyed a high level of reverence in the presence of such accomplished and impactful female lawyers. However, the lack male attendees emphasised the one-sided issue at the heart of the discussion. This will be an important year - 2023 marks the promise for significant change regarding the incidence of sexual assault which Australia has been needing to confront for decades.

Footnotes

1. Jehanne Teo, “In Conversation: Improving the Treatment of Sexual Assault Survivors,” ANU College of Law (The Australian National University, March 3, 2023), https://law.anu.edu.au/event/ conversation/conversation-improving-treatment-sexual-assault-survivors.

2. ANU College of Law, “Anu College of Law Visiting Judges Program,” ANU College of Law (The Australian National University, January 1, 1970), https://law. anu.edu.au/visiting-judges-program..

3. ibid

4. Christopher Knaus, “Bruce Lehrmann Retrial: Act Government Seeking to Urgently Reform Video Evidence Loophole,” The Guardian (Guardian News and Media, November 17, 2022), https://www. theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/ nov/17/bruce-lehrmann-retrial-act-government-seeking-to-urgently-reform-video-evidence-loophole.

5. Rachel Riga, “Stealthing to Attract Maximum of Life in Prison under New Laws to Be Introduced next Year,” ABC News (ABC News, November 23, 2022), https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-1123/qld-rape-sexual-assault-stealthingnow-illegal-under-new-laws/101629352.

6. Dominic Giannini, “Sexual Consent Laws Go under Spotlight,” The Canberra Times (The Canberra Times, November 29, 2022), https://www.canberratimes. com.au/story/8000925/sexual-consent-laws-go-under-spotlight/.

The event:

The ANU Visiting Judges Program is an initiative at the ANU College of Law that provides students with ‘the opportunity to engage and interact with judges and their perspectives on working in the law’ 2. Students read a lot about judges and rarely interact with them, so being able to ‘identify more clearly what judges do, their journeys through the profession, and the life lessons that they have brought to the practice of law and judging’ is a great opportunity for ‘empowering and inspiring’ ANU law students 3 .

As part of the ANU Visiting Judges Program, the Hon Helen Murrell SC and former ACT Senior Prosecutor Katrina Marson took part in a discussion concerning the treatment of sexual assault survivors in the judicial system in the ACT. This discourse was especially relevant in light of a recent high-profile case 4, which have set the tone for 2023 as the year to reckon with the institutional and systemic failures of our justice system.

The speakers:

The Honourable Helen Murrell SC, the former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the ACT, was the first woman to be appointed Chief Justice after an illustrious career overseeing numerous courts and tribunals. Notable among these is her former role as Deputy Chairperson of the New South Wales Medical Tribunal and also first Senior Judge of the Drug Court of New South Wales. During her time as a District Judge in New South Wales, her Honour personally witnessed the low rates of sexual assault convictions, contributed to by harsh cross-examination and the consistent ‘failure’ of complainants to provide evidence that could be trusted ‘beyond reasonable doubt’.

Katrina Marson is a criminal lawyer and advocate for comprehensive sex education and for law reform surrounding sexual violence and assault. Formerly employed in the ACT DPP specialty family violence and sexual offences units, Katrina has seen firsthand the inaccessibility of the justice system for victims of sexual assault and sexual violence due to re-traumatisation. In 2018, Katrina found new purpose in her appointment as Director of the team implementing the criminal justice recommendations of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in the ACT.

Memorable among the sea of recommendations was the use of investigative interviews as evidence in chief, and also improving police responses to reports of historical child sexual abuse.

Moderating the discussion was Professor Lorana Bartels, who is a Professor of Criminology in the Centre for Social Research and Methods at ANU and an Adjunct Professor at the University of Canberra and University of Tasmania.

The discussion:

The discussion stepped the audience through the pre-trial to trial process. The pre-trial process sees complainants who are new to the prosecutorial process attempt to navigate a labyrinth of a system. Saying such an experience is difficult would be an understatement. Furthermore, 1 out of 10 sexual assaults are reported, and approximately 10% of those reported result in convictions.

While the engagement of prosecutors in familiarising the complainant with the legal system is adequate, policy should be enacted to ensure all prosecutors have adequate contact with complainants not only pre-trial but also post-trial to better understand the complainant’s court experience and to establish measures to better that experience. The practice of prosecutors should also enhance focus on managing complainant expectations considering the extremely low rates of prosecution. This could be executed in a way that prepares complainants for a long process that may cause re-traumatisation by communicating the broad purpose of the justice system. That is, to rehabilitate those guilty of criminal offences justly and in proportion to the offence committed.

Coming to the trial process, there was an emphasis on using the recorded interview of the complainant as evidence-in-chief. The idea behind this recommendation is that it replaces the complainant from having to again recall the events of their traumatic experience thereby avoiding re-traumatisation in that instance. As you may recall, this idea was a standout recommendation of the most recent Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in the ACT. While special measures are already in place during the trial process to prevent re-traumatisation, such as the giving of evidence by the complainant from a separate room, it was argued that more radical improvements are necessary, notably moving the complainant’s cross-examination to earlier in the trial process. However, it remains to be seen exactly how the fundamental succession of trial proceedings can be altered.

It was agreed that the cross-examination of the complainant was the most common issue in trials where the jury could not be satisfied on the evidence ‘beyond reasonable doubt’.

It was said here that the nature of the defence counsel’s questioning has long been to blame. While the culture of cross-examination has since imposed responsibility on defence barristers to ask responsible and applicable questions to not humiliate the witness, it was noted that barristers often do not fulfil this responsibility and rely on the judge to intervene in the line of questioning to prevent further distress to the witness.

The impact

While this discussion did not explore the effectiveness of sexual assault laws in determining fault, it is especially relevant in light of the implementation of affirmative consent laws in New South Wales on 1 June 2022, as well as the passing of affirmative consent laws in the ACT in November 2022 which are yet to come into effect 5 . Of course, I have to pay homage to my home state of Queensland, which passed legislation criminalising “stealthing” in November 2022 - although this has yet to come into effect. This multistate adoption of affirmative consent models instigated the Senate to refer an inquiry into the current proposed sexual consent laws in Australia to the Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee with findings due 30 June 20236 . Stay tuned for Issue 2 coming next semester.

The STOP Campaign, a Canberra-based organisation working toward tertiary communities free of sexual violence, supports the ACT consent law reforms as a positive step toward preventing sexual violence by improving the reporting rates of sexual assaults and also conviction rates. The main objective of these reforms are better outcomes for survivors in our justice system. However, given that a key part of the Senate inquiry is investigating the operation of consent laws in different jurisdictions where they apply, concern has been expressed by some legal experts that the consent laws will not impact conviction rates. Like Katrina Marson, the same experts emphasise that reforming societal attitudes in respect of misconceptions about consent and sexual assault through comprehensive sex education may be more likely to have a greater impact on mitigating sexual assault and sexual violence in combination with affirmative consent laws.

The confrontation

2023 is not only a return to normal, but an opportunity for change. The systemic issues in our justice system that affect victims and survivors of sexual assault and sexual violence are pervasive and at long last must be addressed. Too many lives have been ruined, and too many voices have been drowned out by archaic trial processes and a legal system that has false notions of vulnerability and trauma tied to truth and fact. Something has to be done. 2023 is the year to confront the justice system.

In Law: An interview with Scott Phillips

By Callum Florance

By Callum Florance

In Law is a Peppercorn series that features an interview with a practicing member of the Australian legal community. For this edition, I have the pleasure of interviewing Scott Phillips, a partner at Arnold Bloch Leibler (ABL).

Scott works in mergers and acquisitions but has a broad practice that spans shareholder activism, equity capital markets, joint ventures, start-ups and traditional M&A. Originally from New Zealand, Scott got his law degree at Otago University before spending a year and a half working for Bell Gully in Auckland and then 11 years at King & Wood Mallesons in Sydney. He has been at ABL for 5 years and has been lucky enough to work with and learn from a long list of distinguished lawyers and clients and work on some of Australia’s most complex and award-winning transactions .

Q1: What do you credit as the reason why you decided to pursue a career in law?

I grew up in a small farming town in regional New Zealand and while I was an ambitious kid, I was very naïve when it came to what future career opportunities might be available to me. My brother and I were the first generation in our family to study beyond high school and I didn’t know anyone who had gone on to work in the corporate world in a big city! My focus throughout high school was initially on medicine or law, primarily because they were the most difficult fields of study to get into and, in my mind at least, carried the most prestige. Once I got to Otago University, my horizons were expanded enormously. I had the privilege of being introduced to a wide network of current and former students and lecturers who were doing all manner of interesting things at university and out in the world.

I loved studying law but it wasn’t until a summer holiday job at one of New Zealand’s leading law firms that I decided I really wanted to pursue it as a career. The ability to apply the skills and knowledge gained at law school in creative ways really appealed to me.

Q2: What was your law school experience like, and do you have any fond recollections of your time at law school?

I think the law school community was one of the most interesting and vibrant groups of people I have ever had the privilege of being part of. It was a very diverse group in some ways. There were those who came from families with multiple generations of lawyers and judges and others who grew up on farms. Students from big private schools and others from remote public schools. Yet everyone seemed to be very similar in some really important ways. The students were highly intelligent, thought about things deeply and there was a real sense that we were learning something special. We were also budding lawyers, so of course we were constantly arguing and challenging each other.

Q3: What opportunities would you recommend that law students should seek out, including ones that you experienced/wish you experienced in hindsight?

Do not take your relationships with your peers for granted. It is easy to get myopically focused on academics and just surviving law school. But if your cohort was like mine, the most valuable part of the experience may be the networks and friendships you make along the way.

I know that’s all pretty cliched, so for some practical advice: find excuses to spark up conversations with other law students, join clubs, enter competitions. Go to lectures in person! The juice is worth the squeeze.

Graphics by Callum Florance

Aside from life-long friendships, this will give you a deep pool of experience to tap into as you move into post-uni life and try to “bluff” your way through the real world. How do law firm interviews work, what’s the difference between all these firms, do I even want to work in a law firm, what else can I do, how do I get an associateship, do law firms value masters degrees, will people judge me if I eat KFC at my desk? Spoiler: don’t eat KFC at your desk in a law firm – hide in the back of the restaurant while you nurse your hangover like a normal person.

Q4: What does participating in law societies contribute towards a career in law? Is there a trade-off between participating in a law society and participating within the firm?

I’ve never really participated in the law societies that I have been a member of. I can’t speak for all firms or all paths but based on what I know, I’d say as a young lawyer in a large commercial law firm 1) you are going to be working much harder than you did at law school and at times you will just be surviving and 2) because of that, the bar to distinguish yourself is surprisingly low. Write a journal article, participate in a law society, organise a social function at your firm, pick a niche firm precedent document and work really hard to improve it. Do one of these things and do it well and people will notice. Little things like this can have a big impact on the perceptions of you within a law firm. In the scheme of a year’s work, spending another 20 hours working on a side project is both nothing and a herculean undertaking. Just check with someone a few years more senior than you before you pick your project to make sure it is going to be noticed and valued and that you will get credit for it.

Q5: How have you managed the inherent tension in the legal community between comradery and competition (e.g., placing the court above clients, vying for positions whilst maintaining friendly connections with your fellow lawyers, etc.)?

There is much less tension and competition among lawyers than I thought there would be. I work in a transactional practice which means that most of the time my clients engage me to help them get a deal done. So even if our clients have conflicting interests, the respective lawyers understand and respect each other’s role. I’ve very rarely experienced point scoring or open hostility between lawyers. Between clients, absolutely! But clients hate it when they think their lawyer is just trying to ‘out-lawyer’ the other side and for that reason most lawyers either have that attitude beaten out of them early on or they don’t survive.

Q6: What are some of your key takeaways from your experience working in law firms, including the best ways to succeed and thrive?

I think that a career in a commercial law firm is a very low risk proposition. I don’t mean that you are guaranteed to succeed. What I mean is that your ability to succeed is almost entirely up to you (and the sacrifices you are willing to make!). If you are smart enough, and if you get in the door you almost certainly are, and you work hard and dedicate yourself to a life of learning and honing your skills you will have a very successful career.

For many people they decide that it is not what they want. That the sacrifice is not worth it. That’s fine and obviously a deeply personal decision everyone has to make. But compare that risk/reward proposition to a lot of other potential careers where your ability to succeed depends on being at the right place at the right time. There aren’t many overnight success stories in law firms but at the same time, there aren’t many limits on what you can achieve if you commit to it.

Q7: Does working on the same law specialisation across jurisdictions help with a legal practice, or is it better to work closely with your colleagues in the other State offices? Or both?

At ABL, we have a really strong culture of sharing knowledge and bouncing ideas of each other. Rarely does a day go by where I won’t chat to one of the other Partners or Senior Associates about an issue I am struggling with or that I want to get their judgement on. At the cutting edge, the law is rarely black and white and requires a lot of judgement calls.

This is not something that is only done at the senior levels but should be happening across all levels of the firm. If you choose to work in a big law firm, I encourage you to start doing this from day one. Don’t limit yourself to people in your immediate orbit either. Asking for people’s opinions on tricky questions is a great way to foster relationships across the different teams and offices of your firm. I’ve still never met a lawyer that doesn’t love to be asked for their opinion!

Q8: Why did you want to take the leap into becoming a partner, and were there any challenges you faced in making that transition?

I don’t think it was a huge leap to be honest. One of the great things about ABL is that the structure tends to be very flat and there isn’t a strict demarcation between the roles performed by lawyers of different levels. Every

time you work on a deal, and you should be doing dozens of deals a year, the role you play gets a little more sophisticated and your responsibility expands a little bit.

All going well, after you’ve been doing this job for a few years you’ll be running deals with a team around you. Then one day you make partner and hopefully you find that it doesn’t actually change much and you take it in your stride.

Q9: Is it necessary for lawyers continue to participate in academia beyond law school?

No. However it is absolutely necessary to keep up to date with developments in the law and to never stop learning. For some people they pursue this through further academic study, contributing to academic journals or other industry bodies. While doing a masters always appealed to me, I ultimately decided that the cost of taking a year off in terms of lost earnings wasn’t going to be worth it for me.

Q10: If you could change one thing about the Australian legal community as it operates today, what would it be and why?

I think it is constantly changing and evolving and mostly for the better. The main thing I would change which I think is already changing fairly rapidly is providing greater flexibility to people and recognition that lawyers have lives and commitments outside of work. There are times when the job can be pretty inflexible and of course when a crisis arises it can demand 100% of your time and attention. But there are plenty of times when things can be juggled. I think the industry as a whole is getting much better at recognising and accommodating this and as long as you prove you are committed when it counts I find people are very willing to cut you some slack when you need it.

Pepper Spray – Another Day Another SAlt-led Protest

National Union of Students’ National Day of Action for Climate Change

By Lara McKirdy

Pepper Spray is a Peppercorn series that highlights injustice, criminal law, protests and civil disobedience relevant to ANU students via Peppercorn’s Facebook page and biannual magazine.

I attended the annual ‘National Day of Action for Climate Change’ on Friday 17 March 2023. This year’s rally centres around the Labor Government’s current emission reduction goals. Particularly of interest is the Government’s new Safeguard Mechanism, which applies to facilities emitting more than one hundred thousand tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per year.[1] Labor’s new and improved Safeguard Mechanism has been polished off since its Coalition-era controversy and represents a shining promise for change in the war against environmental degradation. Let me give you a bit of an insight into what went down and what comes next.

What happened?

The National Union of Students (NUS) and the Socialist Alternative (SAlt) groups held the rally in Kambri with an attendance just shy of fifty people. The National Day of Action protest was the second significant one on campus this year to be run by the infamous SAlt student society, following the International Women’s Day protest three weeks earlier.

The National Day of Action is an annual occasion where students around the country rally for urgent government action to prevent climate change. Or at least that’s what the rally was meant to be about. Instead, a number of irrelevant political messages like the recent AUKUS deal slipped into the mix, which we will get to in a jiffy. My favourite part of the rally was the radicalisation attempts by not one but two members of socialist groups. I know many people wonder why student activism fails to accurately represent the voices of students at the ANU: anyone who attends a political rally on a particular issue will witness the rally turn into a comment about capitalism/socialism, rather than address the issues that people attended to support. The SAlt’s hijacking and copy/pasting of worn-out messages in each of their protests rather than having a targeted and intellectual treatment of the issues with substantive speakers reflects on the lack of coordinated action by other student groups, or students being put off on campus activism after enduring the SAlt experience. This is a real chicken or the egg situation, but I have to be honest: you won’t see me organising a rally, so maybe SAlty protests are the only physical options on the menu.

I was lucky enough to be badgered by a prominent figure within ANU SAlt who was determined to recruit me to attend various other SAlt-led rallies. Despite being a stranger to me, he was persistent in uncovering my political orientation as if drawing blood from a rock. I repeated numerous times that I was uncomfortable with sharing my political beliefs. It is in poor character for one to abuse their social standing within their community in an attempt to glean personal information from someone and make them feel uncomfortable in an environment that should be focused on collective action over shared concerns. After my experience at the National Day of Action, I would recommend exercising caution in attending these SAlty events.

What’s actually going on?

Returning to the Safeguard Mechanism, this scheme requires approximately 200 of Australia’s largest climate polluters to reduce their net greenhouse gas emissions by 4.9% per year until 2030. The overarching goal of the scheme is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 28% by 2030. The Mechanism is designed to hold emitters responsible for not exceeding baseline net emissions as determined by the relevant Regulator.[2] This scheme represents only one third of the government’s proposed path to net zero.

Outrage over the Safeguard Mechanism from the Greens, the NUS and certain activist groups comes from the scheme’s significant flaw in allowing facilities to use 100% of offsets to meet their reduction targets, without actually reducing their emissions at all. Senator Hanson-Young is particularly frustrated with this scheme when, during the most recent Senate Estimates, she questioned no more than 15 high-level public servants who were unable to provide her the exact number of facilities that planned to use 100% offsets to meet their reduction targets.[3] The lack of information surrounding this figure is particularly concerning and suggests a somewhat blasé attitude toward the effectiveness of this scheme on the part of the government.

To provide a brief history of the Safeguard Mechanism, this scheme was a 2016 Coalition brainchild that initially imposed a cap on the amount of greenhouse gases that big polluters could emit. However, because the cap was set “so high” and allowed so much “headroom” that

emissions increased by seven million tonnes the following year.[4] The Albanese Government, with its 43% goal, reengineered the scheme to reward polluters with safeguard mechanism credits (SMCs) when polluters lower their emission below the baseline. These SMCs function as carbon credits so that when other facilities exceed their baseline obligations, they can buy SMCs or Coalition-era Australian carbon credit units (ACCUs), or alternatively pay a $275 fine per tonne of excess emissions.[5] Interestingly, the carbon credit approach is contrary to economists’ preferred economy-wide carbon price, as they believe such an approach would be more effective not only for reducing emissions but also reducing the costs that go into reducing emissions. A similar approach was adopted by the Gillard minority government, but was repealed after a short period.

What’s it all about?

Returning to the claims made at the rally, SAlt contended that Tanya Plibersek greenlighted the contentious Western Australian Scarborough gas project in May 2022.[6] Upon further reading, this is a simplification. Madeleine King, Minister for Resources, announced the government’s go-ahead for Woodside’s $16.5 million Scarborough gas project the moment she was sworn in, thereby getting the jump on Plibersek.[7] The deeper context of this is Plibersek’s reported friction with right-faction King and also Chris Bowen, Minister for Climate Change, within cabinet due to King’s and Bowen’s alleged disregard for public demand for climate change management and preference to appease largest donors.[8] The combination of the atrocious treatment of outspoken women in Parliament and Labor’s inability to iron out factional frictions and decide on a more comprehensive approach will mean that our own Environment Minister will continue to be constrained in performing fundamental functions within her portfolio.

Secondly, the “rally” took a turn for the worse with a topical shift from environmentalism to the AUKUS agreement. SAlt claimed that the ANU had funded 300 scholarships to train ANU students to man nuclear submarines in preparation for “the war with China.” If you think this claim is a little far-fetched, you are correct. In an address to the Submarine Institute of Australia Conference, there is a notable absence of any such scholarship deal made between the Department of Defence and the ANU. Brian Schmidt (our resident Vice-Chancellor and Nobel-Laureate-in-Chief) discusses recruiting future students to the ANU’s coveted nuclear physics department to prepare them for careers in Australia’s growing STEM industry.[9] The concern around the gap in this industry is both the low rates of students who study high-level mathematics, but also the low rates of women who pursue STEM studies at a tertiary level. Just to play devil’s advocate concerning the “war with China” rhetoric at the moment, it seems to me that this particular address by Brian Schmidt has possibly been

warped into expressing an alternative agenda along the lines of supporting “the war with China”. I think that looking at the relevant evidence for what it is and not what it might be trying to be is always best practice. While I couldn’t find any specific information on funding the next generation of ADF personnel, it seems that Brian Schmidt is acting within the scope of his role in promoting the study of nuclear physics at the ANU. Pretty standard Vice-Chancellor behaviour, rather than a buttering up of AUKUS to get a few more bucks...

What I took away from this event

I hope to see that 2023 is both a return to normal and a year for change. The climate of activism on campus can be made more inclusive and effective by simplifying the political messages being conveyed at the events. As shown at the National Day of Action rally, the addition of questionable and irrelevant claims obfuscated the main political message. While many ANU students avoid protests (probably to not harm their future career prospects in the Public Service), the overall austere culture of activism in Canberra, as seen in the Women’s March at Parliament House in 2021, suggests otherwise. I hope that during my remaining time at ANU, a more representative group (*ahem* ANUSA *ahem*) takes student protests out of the hands of SAlt and demonstrably restores student activism in line with its purpose: to express a want for change together for those without a voice alone.

[1] DCCEEW, “Safeguard Mechanism,” DCCEEW, 2023, https://www.dcceew. gov.au/climate-change/emissions-reporting/national-greenhouse-energy-reporting-scheme/safeguard-mechanism#:~:text=The%20Safeguard%20 Mechanism%20applies%20to,baseline%20determined%20by%20the%20 Regulator, 4.

[2] Mike Seccombe, “The Polluting Flaw in the Safeguard Mechanism,” The Saturday Paper (The Saturday Paper, March 14, 2023), https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/news/politics/2023/03/04/the-polluting-flaw-the-safeguard-mechanism#hrd, 1.

[3] DCCEEW, “Safeguard Mechanism,” DCCEEW, 2023, https://www.dcceew. gov.au/climate-change/emissions-reporting/national-greenhouse-energy-reporting-scheme/safeguard-mechanism#:~:text=The%20Safeguard%20 Mechanism%20applies%20to,baseline%20determined%20by%20the%20 Regulator, 4.

[4] Mike Seccombe, “The Polluting Flaw in the Safeguard Mechanism,” The Saturday Paper (The Saturday Paper, March 14, 2023), https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/news/politics/2023/03/04/the-polluting-flaw-the-safeguard-mechanism#hrd, 3.

[5] Mike Seccombe, “The Polluting Flaw in the Safeguard Mechanism,” The Saturday Paper (The Saturday Paper, March 14, 2023), https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/news/politics/2023/03/04/the-polluting-flaw-the-safeguard-mechanism#hrd, 2.

[6] Bob Brown, “How Tanya Plibersek Can Become a Great Environment Minister,” The Saturday Paper (The Saturday Paper, March 20, 2023), https:// www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/opinion/topic/2023/03/18/how-tanya-plibersek-can-become-great-environment-minister, 1.

[7] Chloe Hooper, “Can Tanya Plibersek Save the Environment?,” The Saturday Paper (The Saturday Paper, September 5, 2022), https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/podcast/can-tanya-plibersek-save-the-environment, 2.

[8] Bob Brown, “How Tanya Plibersek Can Become a Great Environment Minister,” The Saturday Paper (The Saturday Paper, March 20, 2023), https:// www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/opinion/topic/2023/03/18/how-tanya-plibersek-can-become-great-environment-minister, 2.

[9] Brian Schmidt, “Building Australia’s AUKUS-Ready Nuclear Workforce,” ANU (The Australian National University, February 8, 2023), https://www.anu.edu. au/news/all-news/building-australias-aukus-ready-nuclear-workforce, 3.

PEPPERMINT: ANU Law Revue (The Sullivans)

By Callum Florance

Peppermint is a Peppercorn series where we interview and learn more about ANU law students and beyond.

Harvard University has The Harvard Lampoon... Cambridge University has The Footlights... ANU has the ANU Law Revue (affectionately known as The Sullivans for the Law School’s location near Sul livans Creek). Founded in 1972, the ANU Law Revue has been skewering the on-campus, and future Australian, political establishment for generations. Many BNOCs and the children of Canberra’s po litical elite have either been featured in, or roasted by, the ANU Law Revue over the last half century. So much has changed during The Sullivans’ tenure - over eleven Australian Prime Ministers have come and gone, and ANU’s weathered and mouldy concrete (but endearing) Union Court trans formed into the inflammably plastic and blindingly white Kambri Precinct. Throughout all of this, the ANU Law Revue haws had a steady stream of comedic kindling to keep us warm when it’s cold in Canberra. For this edition of Peppermint, we interview and learn about the ANU Law Revue.

The joy of the show

Since universities have a steady stream of young adults, any on-campus comedy needs to be fresh. Fer gus Wall, Co-Director of the ANU Law Revue, notes “[t] he joy of the show is in creating something that is to tally new, that would not exist if not for the cast writing it. For this reason, we write a new show every year.”

This sounds like a difficult clean slating process, but “[w]e don’t ignore previous years’ performanc es,” Fergus says. “On the contrary, we have many sketches from previous years on hand (both those that did and didn’t make the cut in previous shows)... Our aim is to connect each year’s cast with insti tutional sketch writing know-how (through alumni workshops and critiquing previous sketches), so that we have as much technical knowledge at our dispoal as possible to express fresh comedic ideas.”

50th Anniversary Special

In 2022, the ANU Law Revue turned 50 and celebrated with a 50th Anniversary Special. “[L]ast year’s 50th Anniversary Special... was done after the conven tional 2022 show,” Fergus explains, which “included most of the 2022 cast plus a collection of ANU Law Revue alumni (including Stephen Bottomley, former ANU College of Law Dean, and Stephen Parker, former Vice-Chancellor of the University of Canberra) and featured sketches from the inception in 1972 to 2022.”

the ANU Law Revue, as the group “always tries to have... accessible sketches, and sketches that are funny even if you don’t have specific legal knowledge,” Hannah explains. “Our Comedy Festival show was about picking the best of those sketches from our 2022 show, the ones that we knew the audience loved, and putting them on display... So there weren’t any rewrites so much as crafty content selection.”

Nothing and no one is safe!

At first glance the ANU Law Revue might sound like a law-only group (the hint is in the name), but the scope is much broader than it appears. “We like to... have something for everyone,” Layla says, “because there’s such a wide range of styles of comedy and subject matter.”

The Sullivans, ANU Law Revue’s secret name, probably suits it better for its ANU-wide skewering. Layla summarises it perfectly: “Nothing and no one is safe!”

Layla provides a good summary of their new sketches: “Fan favourites include a sketch about a barbershop quartet who accidentally kill someone on their first day on the job as barbers, a Mr Blue Sky parody about LJE, a sketch about Freud’s mum discovering what her son has been up to, a plane passenger coming out of a suitcase, and the show stopping ten-minute epic about queerbaiting in cop shows.” Layla adds, “[w]e also have an all new sketch... which pokes fun at misogynistic male comedians.”

In such a collaborative environment, there is no such thing as self-credit. “Since Law Revue writing is such a collaborative process,” Layla says, “authorship gets a bit murky, so we just credit everything as being written by all of us!”

A sketchy past

Tracing the history of the ANU Law Revue might be tricky, but here is Hannah’s take on how it has changed since it started in the 1970s: “The form of Law Revue has changed a lot over the years, when it first began it was a sort of comedic mock trial, and for a while there, a duo of law lecturers would do a musical duet in the show every year. Some of our knowledge about how Law Revue has run in the past is a bit sketchy (pun intended) because not all years have kept accessible records or photos,

so we don’t have 100% knowledge of what’s come before us. That sometimes makes it fun, like looking through the boxes and boxes of props and costumes we’ve acquired over the years and wondering why there are two full sets of Teletubby costumes.”

Despite this sketchy past, The Sullivans are never afraid of breaking and re-breaking the mould, as Hannah explains: “So basically, the production value, and how the show is performed, has shifted with time, sometimes in ways we don’t remember or have record of. For the last few years we’ve done our show at the Canberra Rep Theatre, which is a great venue with lots to work with and has served us well. Last year was the first time we... performed at the Playhouse for the [50th] Anniversary, and this year was the first time we’ve been at the [Canberra] Comedy Festival. So there’s a lot of moving and shifting with the opportunities that arise.”

Conclusion

With so many ANU clubs and societies rising and falling as fads come and go, it might seem like a miracle that an intensive group like The Sullivans can last for so long. From what you have heard of its members, that is actually its greatest characteristic: university satire and comedy is at its peak because there is a steady flow of new generations coming in with different views, voices, and senses of humour. Many current and former ANU students might have missed out on the 50th Anniversary show, but the catalogue of comedy gold is slowly being digitised for the ages. As Layla notes, you can find “many of our more recent past shows... [on] YouTube.”

To conclude this edition of Peppermint, here is a final outro from our ANU Law Revue (The Sullivans) fam: “Writing a revue is a traditionally long process, we cast the show in March and then spend all year writing many many many many sketches, until finally a select few are chosen, rehearsed and performed in September. Because it’s such a long process, the cast gets super close and we end up working together and collaborating amazingly. So every year the show is hugely different depending on who’s in the cast and their own unique brand of humour. We have such a wonderful cast this year and we would love it if everyone came in September to see just what we’ve cooked up!”

Art by Callum Florance

CREATIVE

Art by Ella Mcgrath

Art by Ella Mcgrath

Chilli Pepper: Spicy Solutions to Law Student Problems

By Chilli Pepper

Ever since I joined ANU Law School, I’ve spent most of my time in the ANU Law Library. I’m quite shy and I don’t talk very much. What can I do to break out of my mould?

– Sir Robert Garran’s bust

Dearest Sir Robert Garran’s Bust, It sure can get lonely up in that musty library! But fear not, as you’d be surprised at the many friends you can meet amongst the library aisles. Bond over your mutual frustrations of Rule 2.2 in the AGLC. Share a coffee at fellows and bemoan how your lecture is too slow on normal speed and too fast on double. Barge into a study room you simply haven’t booked and insist you have, and then make some new friends. Soon you’ll find that the Law School is not so cold and frigid, and that friendly faces are all around. Forever your aunt in agony, Chilli Pepper

I’m a first year law student at ANU and I feel pretty out of my depth. When do you stop feeling like an imposter and start feeling like an actual law student? –

Pinocchio

Pinocchio

Dearest Pinocchio, Being dumped in the middle of a fresher cohort in a busy place like ANU can be a terrifying experience. Bu t I’ll let you in on a little secret: nobody feels like they belong here (except maybe 7th generation lawyer skevs boys, and even then...) Look around you, chances are everyone is freaking out over the same upcoming quiz as you, or just as lost in the Coombs building. Once you can accept we are all a little out of our depth, I’m sure you’ll be feeling like a real boy in no time.

Sincerely your spiciest take, Chilli Pepper

I don’t know if I want to do mooting this year, or do something fun like client interviews or negotiations. thoughts?

– Noodles

Dearest Noodles, Oh Noodles! How wrong you are to assume there is no fun in mooting? What could be more fun than sweating through your best Tarocash shirt as you try to impress the ever terrifying friendly judges. We respectfully submit that you reconsider the doors that mooting opens. After all, an experience at law school without mooting is well... completely moot.

Keep it hot and tasty, Chilli Pepper

What can you actually do with an international law specialisation??

– Odd ECOSOCs

Dearest Odd ECOSOCs,

The possibilities are simply endless. Open your mind and expand your world view. Take a trip to the Hague. Find yourself in New York, sitting at the UN General Assembly. Venture out to the Peace Palace or tour the International Criminal Court. And if all else fails, I’ve heard Coffee Lab is hiring.

From the bottom of my feverish heart, Chilli Pepper

I saw my lecturer out dancing at Mooseheads, but was too shy to ask them to upload their slides to Wattle before their lectures. Did I miss an important opportunity in the history of ANU Law School that would have changed our lives forever ?

–

Mr Moose

Dearest Mr Moose,

Rather than expound any further on this proposition, I simply leave you with the proverbial words of Elkaim J, ‘Extraordinarily, crimes seem to be committed on the way to Mooseheads, at Mooseheads,or having left Mooseheads. I do not know why this is so’. Make of this what you will.

Hot off the presses, Chilli Pepper

Art by Ella Mcgrath

The alarm rings for the 4th time, and you are yet again late to that one dreaded class. You spent too much time caught up in your dreams that you slept through 4 alarms. The clock reads 8:57am, the snooze button really hates you. There were readings to be done, lectures to be watched, questions to be answered, but all remains undone. Ughhhhhh. To be fair, law school does that to people, and you were warned. How to cope?

With such great expectations, the dreams of a law student weigh us down heavily. What were those dreams growing up? Are they achievable or a foregone dream?

***

Dream 1: International Human Rights Lawyer

What Model UN prepared us for. Working to protect the rights of the unprivileged and the vulnerable, speaking on an international forum, reinforcing state sovereignty. These dreams involve you being the voice for those without one. Having the job of informing and educating people of what goes on in every corner of the world; where people’s rights are always infringed on, where women are discriminated against, where the LGBTIQ+ community does not have an advocacy platform. Through your advocacy, you are able to help thousands of people all over the world to have a better life, but also put yourself out there. You get to meet fascinating people who are doing similar humanitarian work to you, and also get to tangibly assist in international protocols AND travel.

Dream 2: Corporate Lawyer

You’re living the dream you always wanted: working in one of the Big 4, representing their business clients and mastering the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). The corporate lifestyle encapsulates numerous business meetings to offer legal advice regarding mergers and starting a company, drafting and negotiating agreements and confidential business documents, shareholders agreements, insolvency agreements, partnerships agreements, etc. It also involves that regular cappuccino with 2 equals in the morning from your favourite barista.

Overseeing mergers and acquisitions and developing relationships with potential clients and shareholders to achieve what’s in their best interests is fundamental to your job. As a corporate lawyer you want to wake up and carpe diem, leaving everything on the table and to become an absolute boss at your job. This also includes inspiring the younger generation and mentoring junior lawyers to also achieve their dreams, like you once had.

Dream 3: Barrister

Prosecutors and applicants. Defendants and respondents. Judges. Waking up and fighting for people and for the restoration of justice. For you to fulfil your Legally Blonde fantasy, ‘like, it’s hard’ and wow everyone with your manipulation of the English language and understanding of social situations. Through being a barrister, you get the respect of everyone in society because you fight for what is right. Serious criminal or civil cases and your independent representation provides you with satisfaction, as you present your carefully constructed arguments in court and also prove what’s right. Further, through working with paralegals, solicitors, and clients, you collaboratively solve problems and contribute to a working society with clearly established rules. You worked hard to get here, and your clients and expertise are a product of developing your specialised skills. Although work gets hard, and the days get long, you are where you want to be.

Dream 4: International Diplomat

Working in different embassies around the world and representing your nation on a daily basis: you are a diplomat. The tasks that are assignedto you vary regularly and provide you with the spontaneity in your life that you crave. Diplomats are put in charge of drafting and editing written reports, providing liaisons with High Commissions and other embassies, and engaging in regular open-ended conversations with officials. As a diplomat, you are a chosen representative that handles departments and projects as well as their finances, and you respond to questions that arise from this public sphere. Most importantly, you communicate daily with people, experience different cultures through finding universal similarities with people, make many connections AND travel.

Dream 5: Prime Minister of Australia

Doing the primary job of this nation. Making Australia Great Again: managing the tension between big ideas to change the history of the nation, with downright populism without reason. Introducing new policies, speaking to leaders of other nations, and having insightful discussions and camaraderie with them. As Prime Minister, you envision becoming a strong, progressive leader who the people adore, and you continue to fight for their best interests and evolve with the changing values of this democratic nation. Meeting leaders from all around the world and sharing different approaches to leadership, your ascension to your position and legal background allow for greater connections. Further, through being a politician, your public speaking skills improve dramatically – you communicate with finesse. Although you face many challenges as a politician, you use this adrenaline-inducing energy and focus on your main goal: improving this nation for the better.

The clock continues to tick, despite the alarms you set. Time doesn’t stop and neither do your expectations beyond law school. No matter how hard it gets, how much you want to fall asleep and forget your existence, it never happens. Next time you wake up on the wrong side of the bed, which happens pretty regularly, don’t forget what you dreamt of. So wake up, go out and make your dreams your reality, so you don’t keep fussing over the snooze button.

***

Laugh, Pronounced ‘Law’ third edition

By Chilli Pepper

By Chilli Pepper

Clean hands

It’s often said that “those who come into equity must do so with clean hands”. This is an unfortunate turn of events for Dr Rudolph Butterfingers, a renowned butter churning specialist who refuses to clean the butter from his hands.

Equitable Remedies: The Musical

What do you call it when you order chips on your tab because you’re still hungry after your burger? Account and an order to make good any deficit.

What do you call it when you ask for the milkshake that they charged you for but never gave you? Specific performance.

What do you call a reservation to attend a performance that features a dancing lion called Cission? Rescission.

What do you call it when you get sick from consuming too much burger and milkshake and you know that you didn’t order ticket insurance on your Cission reservation, but ask the event hosts to find it in their hearts to give you a refund anyway because you’re way too full to see a dancing lion?

Equitable compensation.

Assignment choices

Professor Charlotte Equity Rights, a renowned film professor, was deciding between writing up an assignment for students on the topic of action (to be titled ‘In Action: Violence and Character Development’) or the topic of romance (to be titled ‘In Romance: The Historical Continuity of Love).

Professor Equity Rights chose In Action.

Income according to ‘Ordinary Concepts’

Jared was walking down the street, minding his own business when he saw a street stall called ‘Ordinary Concepts’. Intrigued, he went up to the owner and asked ‘what do you do?’

The owner of the stall replied, ‘we give you wads of cash, and all you need to do is put it in your assessable income’.

Jared looked surprised, thinking it was some sort of laundering scheme. Jared was slightly in debt and needed the money, so he decided to take up the offer. The owner of the stall handed Jared a wad of cash, which he pocketed.

As Jared was walking away, a masked person came over and held him up at gunpoint. ‘Hand over the money,’ the masked person said.

Shocked, Jared handed the wad of cash over. The masked person walked away, giving a thumbs up to the owner of the stall.

Jared turned back and walked up to the owner of the stall, infuriated.

Jared ranted: ‘who do you think I am, some sort of chump? You offer me a wad of cash, like a piece of bait on a fish hook, and then your buddy over here takes it and scares me in the process? What sort of ringer are you playing at? What sort of scheme is this?’

The owner of the stall responded, ‘an allowable deduction’.

Maitland in the clouds:

Maitland said that “Equity without common law would have been a castle in the air, an impossibility”. Yeah okay, Maitland clearly didn’t watch Howl’s Moving Castle.

Opinio Juris

Let me tell you the story of Opinio Juris. Opinio was a cerebral character, often stalking the lecture halls and the law library. Opinio would watch students from a far, observing their practices and listening to all that was said. When students shared notes, Opinio would often ask for a copy and peruse its contents. One day, students arrived at the law library and were surprised to find a set of rules that Opinio had sticky taped to the door. Opinio proclaimed that these were binding customary laws for all law students in the law school, based on what he saw were law student practices underpinned by a general belief that legal obligations arose from them.

Here is Opinio’s list:

1. The doctrine of indefinite sniff – If you hear another student consistently sniff in the back recesses of the law library, you must allow that student sniff indefinitely without intervening with a tissue and to only to passively assert your dissatisfaction in communiqué’s to students via the correct channels of text messaging.

2. The doctrine of peculiarly situated – If a student has voluntarily taken over an entire 6-chaired table for themselves, and the nearby resources are claimed, then you must only take up residence alongside them and assert your claim over a portion of the table if the student does not seem like the type to make you uncomfortable in a quiet space.

3. The doctrine of in-and-out – If a student is quite behind on the readings, then the student must spend no more time on campus than what is required to achieve a decent participation mark.

4. The doctrine of insmartus privatia collegus studentius – If a private college student is confident in class despite not doing any of the readings, the student must respond to the lecturer’s questions by rephrasing the question back to them to make it appear as though the student knows what they are talking about, except if the student has inherited recent high-distinction quality notes from the later year private college students and can quickly find the answer in the notes.

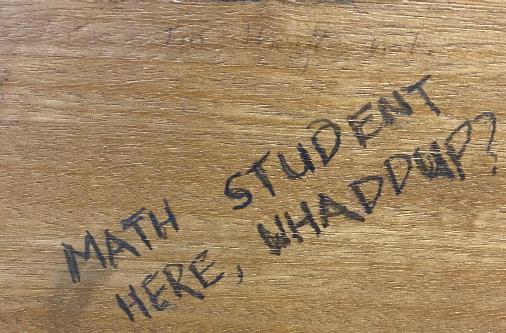

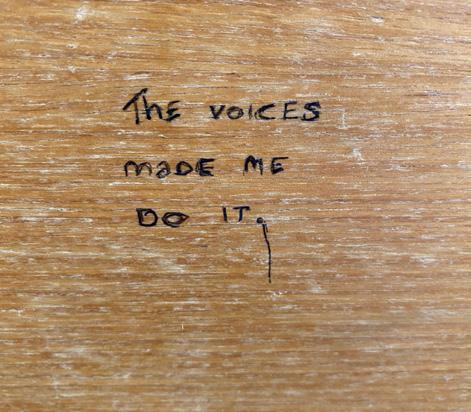

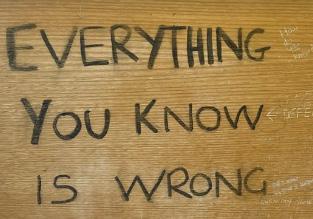

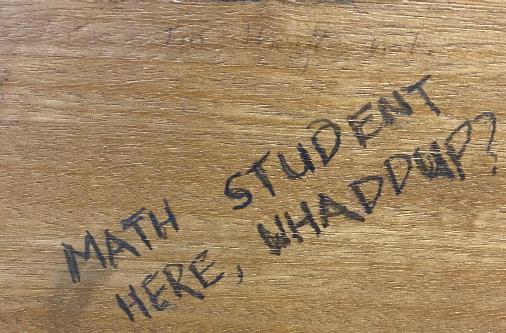

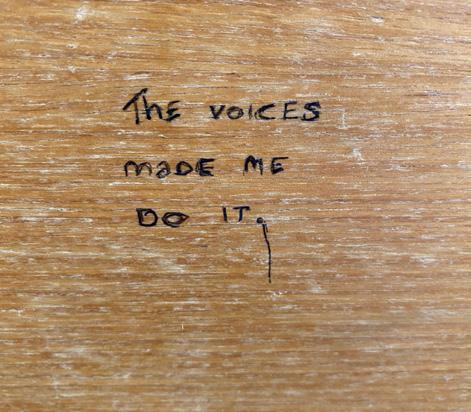

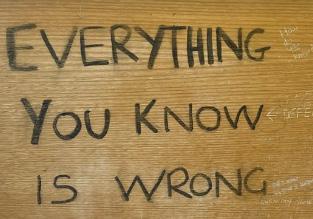

5. The doctrine of frightening signals – If a student has taken residence at one of the single-person desks in the law library, the student has a right to relocate if the desk is riddled with mentally questionable graffiti that brings into question the student’s own mental wellbeing.

6. The doctrine of notes hogus – If a student (scabor) has become friends with another student (scabee) who only puts enough effort into the relationship to scab notes off the scabor without returning the favour, then the scabor has a right to ghost the scabee on social media.

7. The doctrine of champus or buddy no friendus – If a student strikes up a conversation with another student and the other student refers to them as ‘champ’ or ‘buddy’, the ‘champ’ or ‘buddy’ has a right to immediately exit the conversation because it is likely they are being made fun of, except if the person is known to be genuine or from Queensland (except Brisbane).

8. The doctrine of Garran’s nose – If a student rubs the nose on Sir Robert Garran’s bust in the law library each time they walk past it, the student is more likely than not to get scaled up to a distinction or higher on their final mark for their weakest course.

Unfortunate De-Briefing

A hot-shot lawyer was walking in the suburbs when they took out a pair of undies from their leather briefcase and placed them on a beautiful white picket fence. The owner of the fence came storming out of their house and said ferociously, “this is unacceptable! What do you think you’re doing?!”

The lawyer responded, “I’m serving my briefs to de-fence”.

Art by Ella Mcgrath

By Chilli Pepper

Pepperoni Observational News Corp is a Peppercorn series that delivers satirical news and reporting via Peppercorn’s Facebook page and biannual magazine, and definitely has no affiliation with Woroni or the ANU Observer and any allusions to affiliations with these news outlets are false and misleading and should not be made or considered.

Our top stories for Semester One, 2023...

John XXIII College boy very confident in tutorial without doing the readings

Richard Winterbottom, 19, is a stand-out voice in his Environmental Sociology tutorial, despite never open- ing a single assigned reading on Wattle.

“I am just a very confident and broadly intelligent guy,” said the Toorak-sider, who was also the head boy at his Melbourne private school.

“I know there are plenty of introverted students who have done the readings and might be able to partici- pate more effectively in a discussion of the course con- tent,” Richard added. “But I really like walking in nature and looking at trees and stuff, so I think I am a pretty good source on environmental society.”

We asked others in the tutorial to confirm his claims. Their broad consensus was that letting Richard talk about nothing for 60 minutes was less harmful to their social anxiety than being singled out in a tutorial.

Undergrad law student too far into nine- year part-time double degree to drop out

Lilian Fun, 25, started her double degree in law and arts seven years ago and is too far gone to drop out.

“I got into ANU law when I was, like, 18 years old and in my third year I decided that I’d never pursue law as a career,” the undergraduate law and arts student said. “I went part-time to support myself and have slowly tak- en on more and more work as the cost of living grew,” Lilian noted, “but this has also meant fewer courses being ticked off for my double degree.”

We asked Lilian whether it would be easier to drop out of the law degree now, rather than take on more and more HECS debt.

“It’s like gambling,” Lilian said. “HECS debt is tied to inflation and the job market is pretty strong, so I’m betting that the HECS debt bubble will eventually burst and that the job market will continue to be good for graduates when I finish... what I call the double down!”

Sensing a lack of confidence on the bet, we asked Lil- ian whether she was sure about her decision to stick with it.

“My 18-year-old, high-ATAR confidence led me to where I am today,” Lilian added. “Why not fulfil that 18

year old’s dream and complete the double, regardless of the negative impacts it’ll have on my real income?”

Lilian is expected to complete her studies by December 2025, but could finish her arts degree by December 2023 if she dropped out of her law degree today.

Uni Senior Resident does work of 10 employees, gets 5% discount on accommodation fees

At a corporate ceremony earlier this week, UniLodge Senior Resident Miranda Klein, 20, was presented with a 5% accommodation fee discount voucher as compen- sation for her work.

“I won’t lie, I’m pretty tired,” said a trembling Miranda. “When I signed up for this, I thought it’d look good on a resume... I didn’t realise I’d be doing the work of like 10 employees.”

In the past year, Miranda has regularly:

- vacuumed and mopped the floors

- been on-call overnight for drunk and locked-out students

- accompanied students with psychological issues in ambulances to the ER and waited with them in the ER until the early hours of the morning

- supported 150 students on her level that she has been assigned to look after

- counselled at least half of those students needing support

- been the bouncer and RSA officer for UniLodge social events

- planned and managed those social events to make sure no one gets hurt

- answered emails and calls on behalf of UniLodge

- cooked meals for students who cannot afford dinner

- managed the UniLodge budget

- represented UniLodge corporate at regular Interhall Events, shareholder General Meetings, and Board Meetings

- fixed plumbing issues with the outdated pipes

- maintained a coin dispensary for students needing to wash their clothes because no one uses coins anymore and UniLodge still makes you pay to use the washing machines

- hosted weekly yoga classes on the lawns - fired several UniLodge employees on behalf of UniLodge corporate - provided totally under the table and unofficial con tract and property law advice to students that Uni Lodge successfully lobbied the ACT Government for something called an “Occupancy Agreement” that is not covered by the Residential Tenancies Act and, no, UniLodge residents do not have the same rights as tenants in the ACT and have basically signed their life away on an unfair contract that are the result of severe power imbalances and, no, they will never be able to escape until they are forced to leave in January the following year and asked to pay $200 for a “cleaning fee” even though their apartment had been entirely covered in a layer of grease since they arrived and was never addressed the entire time they were living there.

We asked Miranda if the 5% discount on her accommodation fees was worth it, given that she is basically an employee of UniLodge and the discount only amounts to her being paid 30 cents per hour.

“Not worth it at all,” Miranda said with unsteady hands. “It costs $621 a fortnight for a room at UniLodge, so I’m already paying well-above the market rate for this room... even with a $31.05 fortnightly discount.”

Miranda continued, “I could be living my best life partying in a fun, run-down Turner house with my friends, but instead I’m basically the living embodiment of a superwoman. This is where the gender pay gap starts.”

Miranda pointed out that she had been assigned a Residential Advisor to support her, but she has been unable to locate them since the start of the Semester. We visited the room of this RA on several occasions and were able to confirm Miranda’s suspicions that the person could not be located and is likely of a supernatural or ghostly origin.

We asked Miranda if the 5% discount on her accommodation fees was worth it, given that she is basically an employee of UniLodge and the discount only amounts to her being paid 30 cents per hour.

“Not worth it at all,” Miranda said with unsteady hands. “It costs $621 a fortnight for a room at UniLodge, so I’m already paying well-above the market rate for this room... even with a $31.05 fortnightly discount.”

Miranda continued, “I could be living my best life partying in a fun, run-down Turner house with my friends, but instead I’m basically the living embodiment of a superwoman. This is where twhe gender pay gap starts.”