REBEL WOMEN FROM THE APOCRYPHA MARCELLE HANSELAAR

Many years ago, my friend Lex van Delden gave me Great Women of the Bible, a large book which illustrated the tales of feisty women of old through existing artworks. Eve, Lilith, Delilah, Salome, Jezebel, Judith, to name a few. Throughout my life I had heard references to these heroines: “Don’t be a Jezebel” or “You look like the witch of Endor”. I was curious to find out more about them.

They were the antithesis of nice, good, servile women that society expected us all to be. Furthermore, the outrageous nature of their acts thrilled me. Clearly, like many women these days, they were merely demanding a position of equal power, respect and freedom in a patriarchal society and they got this through wit, ingenuity and occasional violence.

It just so happened that at the beginning of the year, while searching for something else, this particular book caught my eye again and I remembered my old friend, when he gave it me, saying “this is so you”. While skimming through the pages, I concentrated on finding an image, sentence or paragraph which would hit the spot. When it did, I would close the book and let my imagination take me wherever it wanted to go.

I began with Eve, traditionally accused of the downfall of men. I retold her story, depicting her as playfully taking the upper hand while comforting a bewildered, apprehensive Adam. From then on, a whole array of disobedient, strongwilled women followed: those who got their own back or who changed the laws of predictability.

The different ways these heroines outsmarted powerful men with their skill, wit and determination have inspired countless interpretations throughout the ages. We all want in one way or another to activate this subversive energy. As it was then, so it is now.

To all the rebel women out there.

I salute you.

Marcelle Hanselaar

IAlthough I had bought prints by Marcelle for both myself and Pallant House in Chichester, and although we had chatted on Instagram, I did not meet her face-to-face until the Original Print Fair at Somerset House in 2022. We soon discovered that we shared a dark sense of humour and a liking for difficult subject-matter. We started talking about the present project because I had just told her dealer, Julian Page, that I would buy ‘Sisera’s Mother’. When Marcelle discovered that in a previous life (that is, 1980s Britain) I had completed a Ph.D. in biblical criticism, she asked me to write something to accompany this series of prints which interprets stories about assertive women taken from the Judaeo-Christian biblical tradition.

Well, some of you will know how it is: you enter your 60s and start to revisit your youth. I jumped at the chance to re-examine the tales of women which I had studied either in Hebrew or Greek as an under- and post-graduate. In two cases Marcelle was using stories which had been central to my thesis. After a bit of good-natured argument, plus some trial-and-error on my part, it was agreed that I would write an introduction to the series of fifteen prints, and then provide two paragraphs about each print: the first would provide a summary of each story’s treatment within the Jewish literary tradition, and the second would provide a personal interpretation of each printed image.

We did umm and ahh a bit about those first paragraphs: too much detail, not of interest to the average art lover, just too boring for all but academic nerds? And then Marcelle had a moment of illumination. She enthusiastically cornered a visiting Jewish friend from Tel Aviv. Since he had been born and educated in Israel, she assumed that he would be familiar with the stories of the Rebel Women which had got her so fired up. Alas, he had to tell her that he did not know them at all. She had better luck with a Muslim friend from Jeddah who told her that some of the stories, in different forms, could be found in the Quran. Urgent email to me: ‘It is important to give the stories the kind of setting you suggested.’

IIMarcelle does not come to the stories from a faith background. She had a choice of classes at primary school: needlework or bible stories. She chose the stories and remembers the frisson of hearing how the dogs ate Jezebel’s corpse (well, she would, wouldn’t she?). Later, paintings formed a stimulus to her thoughts. One can see the influence of Lucas Cranach the Elder’s ‘Judith with the Head of Holofernes’ (Staatsgalerie Stuttgart) on the way Judith holds the head in Marcelle’s own portrayal of the scene. ‘These ancient imaginary narratives give us a much-needed energising subversiveness.’ She likes the way the women fooled powerful men and made them look absurd – or worse –without making themselves look virtuous.

‘I

Our email exchanges brought out several points which clarified for me Marcelle’s creative process. There are two prints involving the women of the household of Lot, a kinsman of the patriarch Abraham. One involves his daughters being offered up for gang-rape in order to save two male guests from assault. The other involves his wife being turned into a pillar of salt. But Marcelle, I asked, why have you left out Lot’s daughters getting their father drunk so that they can have sex with him to ensure the survival of their family line? It seemed such a juicily subversive story. Simple reason: she had already created two prints on this theme of two women sexually assaulting their father back in 2006.

It is important to understand that Marcelle is not illustrating the texts but using them as jumping off points for the expression of her own interpretative responses to the stories. In the late 19 th century James Tissot created 350 watercolours of ‘The Life of Christ’ which were archaeologically correct in their details. In their day they were a runaway success, but today they seem flat and sterile in their attempt to be ‘correct’. Marcelle brings the biblical figures to life by making each one an expression of Everywoman. She does this by quoting details from many temporal sources. I can see Golden Age Dutch references, Weimar films and 21 st century baseball caps. All are grist to her mill.

Time to talk about the term ‘apocryphal’. The biblical narratives did not just spring into being. There was a long gestation process in which elements of folklore, legend, myth, history, religious experience and theological speculation came together in individual books (like Genesis), which then became parts of larger units (like the first five books of the Bible: the Jewish Torah, the Christian Pentateuch), which in turn became parts of even larger units (the Jewish Bible known as Tanakh – short for Torah, Prophets and Writings – which is equivalent to the Christian Old Testament.) These works became ‘canonical’ for Jews and Christians, accepted as the inspired word of God.

However, there were other strands of narrative within the Jewish literary tradition which scholars labelled ‘apocrypha’. This is a Greek term which means ‘hidden’... and it is quite hard to pin down. I will suggest here that there are three ways in which it is used. Firstly, there is Apocrypha with a capital A. This refers to books like ‘Judith’ which are found in the Greek version of the Old Testament, called the Septuagint, but not in the Hebrew. Secondly, there are rabbinical commentaries on and elaborations of the Hebrew text, and these are called ‘midrashim’. Finally, there is a very broad use of the term to suggest the appearance of folkloric elements within narratives.

What Marcelle has done is to look at both canonical and apocryphal stories and then weave from them her own magic, which is itself ‘apocryphal’ because she is not an illustrator,

but an interpreter. That is exactly what you see happening in the midrashim – a commentator takes a narrative and adds their own understanding. The narrative is thus brought to life for a new audience and gains a layer of meaning. Marcelle is a secular artist in the early 21 st century with a more down-toearth approach than the rabbinic commentators of the past, but she is within a tradition. Sometimes she illustrates something found in the canonical text (Potiphar’s wife) and sometimes she illustrates details which are apocryphal (the Queen of Sheba).

fathers or their husbands. When Marcelle’s curiosity was piqued, and she began to research the stories, she concluded that ‘these women are early feminists, standing up to male domination’. She approved of their ‘assertiveness’ and noted that ‘in women it is still often criticised or curtailed’. Sometimes she bestows an assertiveness on characters who have no voice in the original narrative. Thus in ‘Lot’s daughters’, we see two women reacting against being treated as sex objects.

IVFinally, we come to the idea that these women are rebellious. Marcelle has used the word ‘feisty’ to describe them, and it sums them up, with one meaning being more apposite for one of the women, and another meaning more apposite for another: lively, determined, courageous, spirited, spunky, plucky, strong-willed or adamant. What the word does not imply is that every woman is a ‘good’ one – and I do not mean simply from a male perspective. After all, even a fully paid-up feminist might question Salome and Herodias as role models when they connive at the murder of John the Baptist. However, I might be wrong. I can hear in my mind the echo of ‘He had it coming’ from the musical ‘Chicago’.

What comes across very strongly in most of the prints is the battle of the sexes. Marcelle is taking texts which come from a patriarchal tradition, in which God is ‘He’ and women are defined socially by their relationship to males: be they their

If I had to choose one print to sum up what Marcelle has achieved in terms of making me think and feel, it would have to be ‘Jezebel’. Jezebel is such a complicated woman. She is a powerful foreigner who worships different gods from the Jewish men who wrote the biblical account of her. We only have ‘their’ truth – meaning a one-sided view of what happened – in which she becomes evil incarnate and the original of every uppity woman who has been labelled a ‘Jezebel’ ever since. But she meets her end, when a military putsch exterminates her dynasty, with great dignity. From childhood I remember her slapping on the face paint and covering her hair before facing her killer. She seems all too apt for our own times.

Mark GolderMark Golder gained his Ph.D. in biblical Hebrew from Manchester University in 1985. His thesis examined how the Tamar story fitted into the surrounding narrative about Joseph.

According to Jewish tradition, Eve (‘Life’) was the second wife of Adam (‘Earth’). In Genesis Rabbah, a midrash from around 500 CE, the rabbis suggested that Adam soon realised that Eve was destined to engage in constant quarrels with him. Like Lilith, Eve gained a negative image in male-dominated opinion because she refused to accept a secondary role. She also stood accused of having an overactive sex-drive and, the biggest blow of all, was held responsible for bringing death for humans into existence when she successfully tempted Adam to eat the forbidden fruit in Eden. Her creation from Adam’s rib, or side, was sometimes used to show her subordination – she came from him, not him from her.

Hanselaar brings out the erotic tension between Woman and Man in her take on this story. On the right-hand side we have the dark outline of a man in a hat and coat. He stands, like a voyeur, watching. Is he God, or the angel who will cast the couple out of Paradise, or the promise of Death to come? Adam and Eve are on a couch, seemingly ready for sexual congress, or so the erection sported by Adam would suggest. He lies on his back, considered the more passive position, and is thereby dominated by Eve. Hanselaar has gone to town on Eve’s portrayal. She is truly top dog and in control. As one hand holds onto Adam’s head, an elegantly stockinged leg thrusts down towards his torso so that the heel of the shoe digs into the flesh of his side, as if seeking to wound the spot of her creation, the spot from which comes her supposed subordination.

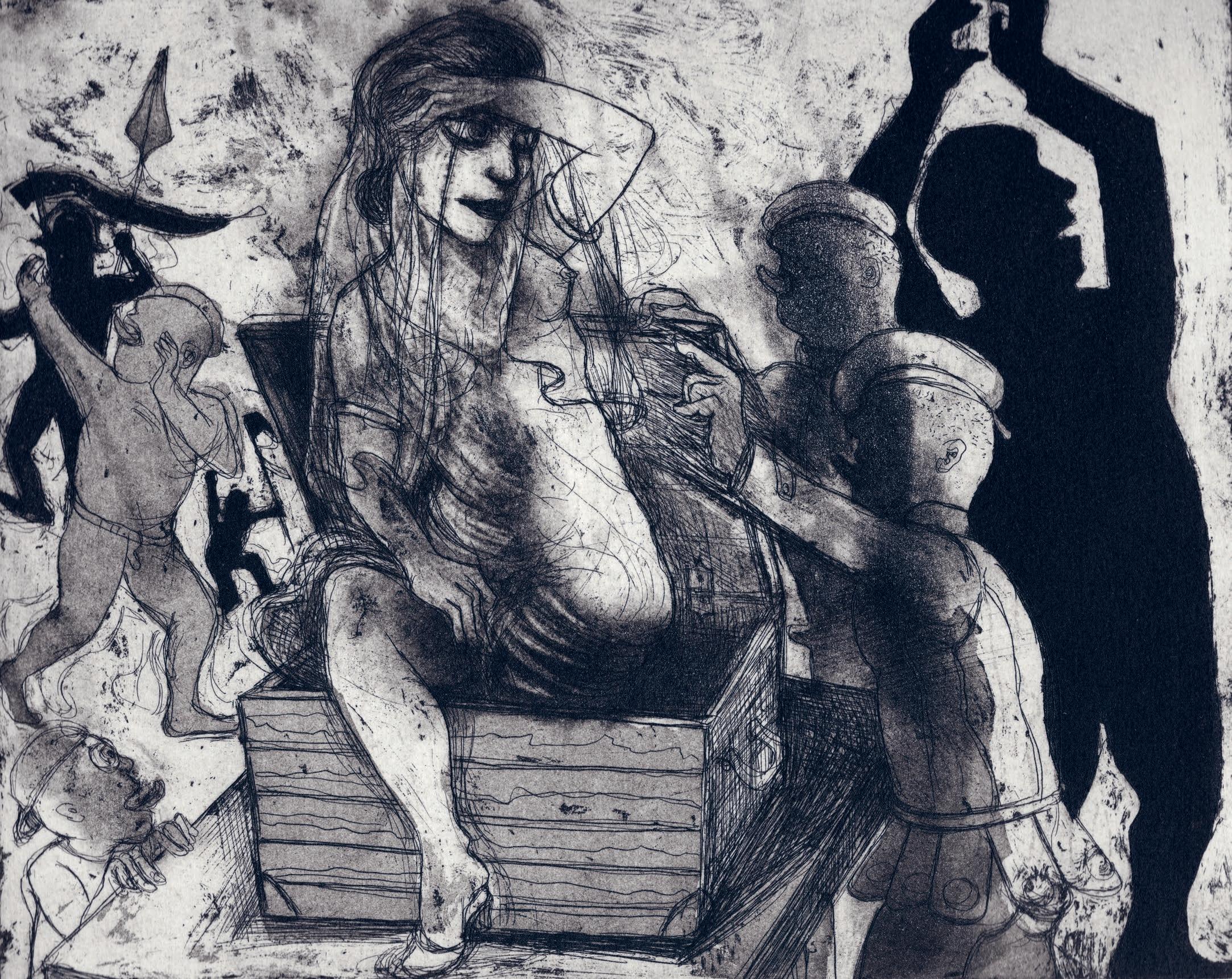

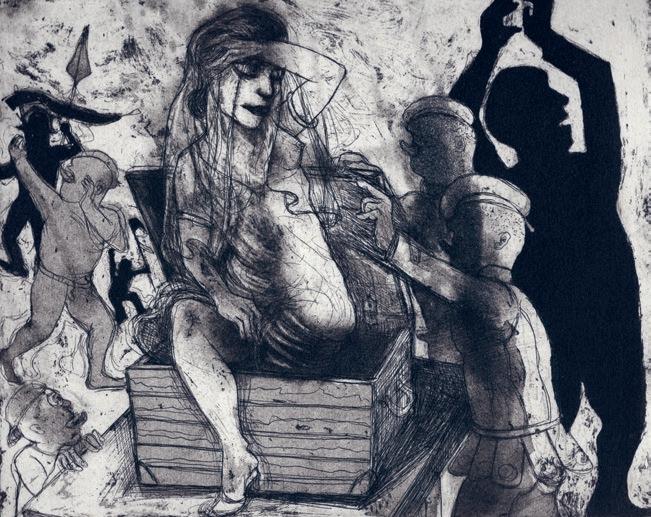

The Treasure, Sarai and Abraham

Abraham is the great patriarch of the Hebrew people in Genesis. Whilst living in Canaan (Israel/ Palestine), he is faced by famine and decides to go to Egypt. He is afraid he will be killed because men will desire his wife, Sarai (‘Princess’). In the biblical version he tells her to say she is his sister, but the medieval midrash, Sefer haYashar, ups the ante. Sarai is the most beautiful woman in the world and Abraham requires more subterfuge: he hides her in a chest. When the Egyptian custom officials go looking for contraband, they find Sarai. She emerges from the chest, haloed in the brilliant light proceeding from her beauty. Each man is driven mad with the desire to possess her, and each tries to outbid the other.

This print is one of the most densely populated in the series. At first in can seem confusing, but everyone has a part to play. Sarai, centre stage, steps out of the chest, like Jesus from the tomb in a renaissance altarpiece. The face of Sarai is dominated by those eyes that can drive men mad with lust. The dark silhouette to the right is Abraham, gesturing his helpless dismay at her discovery. The boy in the left foreground is, with his tongue hanging out, a very straightforward symbol of lust. The guards in the left background, one holding his spear erect, are balanced by the soldier on the right who opens the lid. He is an Everyman figure, inhabiting no one timeframe. He has the cap of a modern soldier, but his buttocks are framed by a Roman-style kilt, as if he has stepped out of a painting by Rubens. This print could have been entitled ‘Beauty conquers all’: ‘Pulchritudo vincit omnia’.

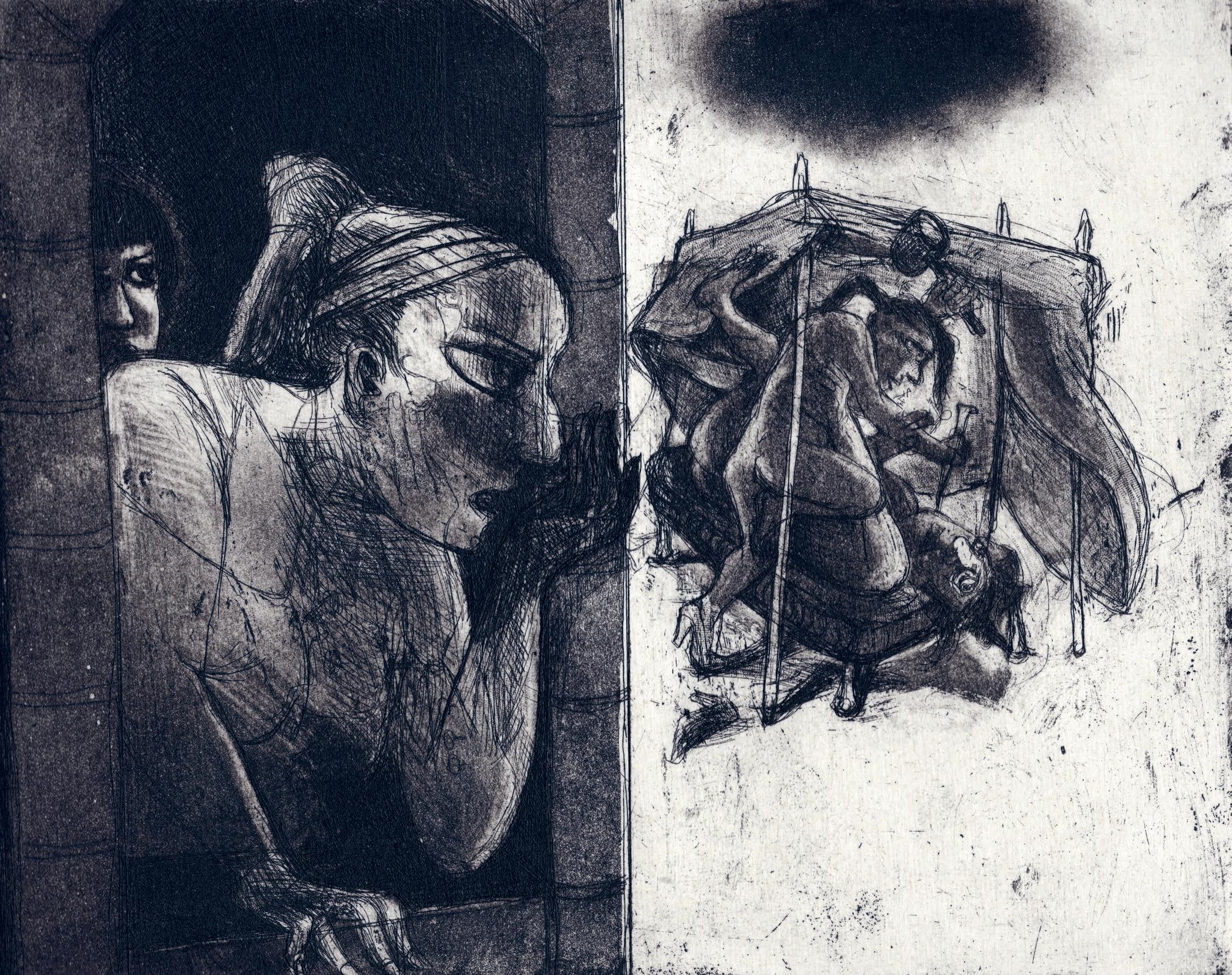

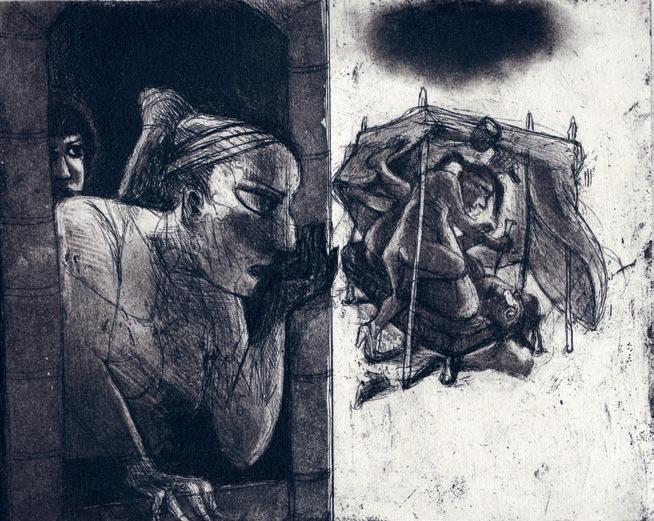

The patriarchal narratives of Genesis are set circa 1500 BCE. Three hundred years later the ancestors of the Jews are fighting the Canaanites for livingspace. In the book of Judges (or better ‘Rulers’), the Israelites are led by the judge Barak and the prophetess Deborah to a great victory over Sisera. He runs for his life and, thinking he is safe in the tent of the Canaanite woman Jael, falls asleep; but he never wakes up because she drives a peg through his skull. Meanwhile, we see through the victory ode of Deborah, Sisera’s mother foolishly gloating over her son’s triumph. In particular she thinks he must be late returning because he’s taking so long to divide the spoil, including ‘a womb or two for every man’.

In this print we get two images for the price of one. On the left and in the darker half of the plate, we can see Sisera’s mother, accompanied by her maidservant, looking out of a window and wondering where her son has got to. There is a total failure of the right-hand side of the print to live up to the expectation captured on the lefthand side. For whereas Sisera’s mother thinks she knows what her son is doing, she is actually blind to reality thanks to pride. She cannot imagine his defeat. But on the right and in the lighter half of the plate we witness the destruction of Sisera. In her tented enclosure, Jael has raised a hammer above the spike with which she will literally nail Sisera to the ground. A little dark raincloud hovers over this scene: a touch of dark humour because someone has certainly rained on Sisera’s parade.

The book of Judith is Apocryphal with a capital A because it is a work of fiction from circa 100 BCE and is only found in the Greek Septuagint version of the Jewish bible. Since medieval times Jews have associated the story of Judith (whose name means ‘Jewish woman’) with the winter festival of Chanukah, which marks the salvation of Jerusalem and its Temple from assault by foreign enemies. Professor Deborah Levine describes Judith as ‘beautiful and bold, pious and violent, seductive and wise.’ She worms her way into the bed of Holofernes, the enemy commander, and, when he is drunk, hacks off his head. Artemisia Gentileschi created a famous picture of this scene, giving the commander the face of the man who had raped her.

Judith is seated as if at a dining table with the recently severed head of Holofernes before her. She has a hairstyle echoing those of the liberated women of Weimar Germany in the 1920s (and, incidentally, that of the artist herself; so, some room there for a Freudian interpretation). This Judith makes me think of Lulu, as played by Louise Brooks in the 1929 film ‘Pandora’s Box’. An apt thought, because Lulu has an eroticism which stimulates lust and violence. With her left hand Judith holds down the head of Holofernes, like a recently butchered pig’s head, and in her right hand she holds aloft the severing knife. It looks as if it is about to carve into the head below. One eyeball or two, Sir? Yum, yum. The dark shadow behind Judith adds a final sinister note to the already sinister proceedings. Dare one say that this is the most ‘amusing’ print in the series – albeit in an undoubtedly dark way?

Yet another tale of male destruction by a female hand comes a little later in Judges. Delilah (‘Night Lady’) will darken the sight of Samson (‘He of the Sun’). Everything about her in the narrative is shifty. She lives in the Vale of Sorek, mid-way between the Israelites and their new greatest enemy: the Philistines. She is an enigma. Unusually we are told nothing specific about her lineage, her status, or her ethnicity. Does this make her another Everywoman? What we do know she is, is a betrayer. She accepts a bribe from the Philistines to discover the secret of Samson’s great strength: his hair. Once it is cut, he is impotent and easy prey. In short order he is taken captive and blinded.

Hanselaar chooses to capture the moment at which Samson is blinded. On the right, her body turned towards the light, we see Delilah clutching the hair of Samson. She seems to be on an upper balcony, and a black-silhouetted figure stands below, ready to catch the hair as it falls. Delilah herself looks back into the dark interior, as if to say, ‘What have I done?’ Meanwhile, the scene to the left is one of unmitigated violence. Samson is almost hidden by two Philistines. His limbs are contorted, as if he is a puppet whose strings have been cut. The man in front holds him down, one leg pinning down Samson’s arm. More disconcerting is the one behind. His face is a mask of malice, and it looks like he is raping Samson. The only clearly seen part of Samson is the eye. How ironic that within a few moments the hovering spike will have blinded him for ever.

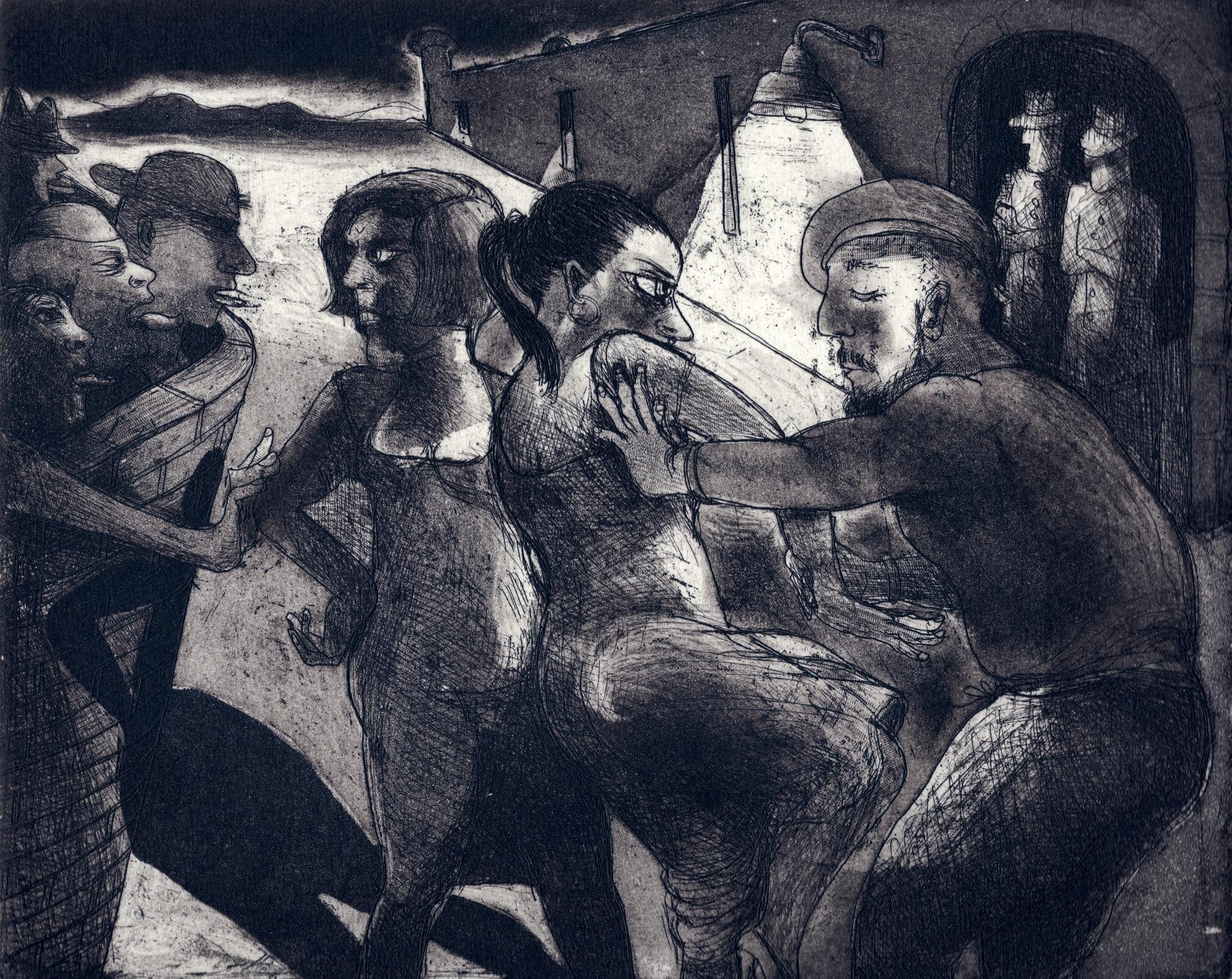

This print comes from the Christian New Testament and records a 1st century CE event. Salome (‘Peace’) is the unnamed girl, ‘Herodias’ daughter’, in the Gospel of Mark, who danced before her step-father, Herod Antipas, and his guests. Her mother loathed John the Baptist, a prisoner of Antipas, because he had publicly denounced her for divorcing her first husband in order to marry Antipas – who also happened to be that first husband’s half-brother. Urged on by her mother, when the lust-filled Antipas promised her whatsoever her heart desired, she asked for the Baptist’s head on a platter. Having given his word in public, Antipas felt honour-bound to give her what she wanted.

Hanselaar creates a figurative frieze across the front of the print which captures the cause of the effect which is centre-stage in the background. On the right we see the gyrating Salome, dancing for all she is worth. She dances in the light, whilst Herodias and Antipas are in darkness. Herodias stands behind her husband, and her hand descends suggestively to touch his crotch. She knows her man: ruled more by lust than by reason. He, meanwhile, sits with one leg up which compositionally allows Salome to see the effect she is having on him. It also parodies the ‘pose of great ease’ which you see in statues of the passion-free Buddhist bodhisattvas. Antipas’ hand touches the lips of Salome. Thus, all three players are linked by anger and lust to bring about the murder of the Baptist. In the background, the black silhouette of a servant carries in his severed head as if bringing the final course to the banquet.

The final story taken from Genesis concerns Joseph, great-grandson of Abraham and the brother of Judah. Sold into slavery in Egypt, he is trusted by his master Potiphar. Joseph is described as ‘well-built and handsome’, just the sort of morsel to tempt the jaded palette of a bored housewife. Unnamed in the biblical account, medieval Jewish sources call her Zuleika (‘Lovely’). She constantly pesters Joseph to sleep with her. Finally, he runs away from her, leaving his upper garment in her hands. She screams ‘Rape’ and produces the garment as evidence. Potiphar believes his wife and Joseph ends up in jail. This is a classic example of the folk tale of the virtuous young man faced by a sexually voracious woman.

For the story to work emotionally there must be a chance that Joseph will succumb because his master’s wife is irresistible. Hanselaar puts her centre stage. She is naked on the bed, deliberately offering herself, and her anger at his rejection is obvious in her eyes and mouth. On the bed behind her is an ape, which in 17th century genre painting symbolised bestiality and lustfulness. Zuleika puts out her arm to grab hold of Joseph’s garment. Cleverly, Hanselaar does not simply show Joseph running away. He seems to be in two minds about what to do: maybe he ought to accept what is on offer? So, he is caught taking a peek through the fingers of his right hand at Potiphar’s wife, whilst his left hand hovers suggestively over his crotch.

Eventually the Judges were replaced by kings. The first one, circa 1000 BCE, was Saul. In 1 Samuel, when Saul seeks to defeat the Philistines, he uses all the legal means of prophecy to get advice. Nothing. In his indecision, he disguises himself and visits the Witch of Endor, a necromancer whom he has outlawed. Although she realises who he is, he promises her immunity if she summons the shade of the prophet Samuel. The latter appears and foretells the destruction of Saul and his sons. The Jewish tradition had problems with the calling up of shades. The 2nd century BCE Septuagint reduced the woman from witch to ventriloquist – thus suggesting it was all a fraud.

Traditional artistic interpretations of this story often centre on the men and push the woman herself to the side-lines, if they show her at all… but this is not Hanselaar’s way. The witch dominates the left-hand side of the scene, almost filling the scene from top to bottom. She is an embodiment of the female outsider, showing her private parts defiantly beneath clothing held together with male braces. In her right hand she carries a vial containing a hallucinatory drug to transport her into a visionary state. Blindfolded she sees what others cannot. Before her, in the role of suppliant, skulks Saul. He is caught between submitting in order to get what he wants and fearing the consequences of breaking his own law. Behind him a servant refuses to watch, whilst one hand is between his legs as he wets himself with fear. This print is awash with male fear in the presence of female power.

The original story of the Queen of Sheba visiting King Solomon is set in the 10 th century BCE and found in the biblical book of 1 Kings. She comes to test his wisdom, but also brings gifts of spices, gold and jewels. If she existed, she probably came from Yemen in search of a trade agreement. The 1st millennium CE midrashic Targum Sheni to Esther went to town on this story. The text is full of folkloric colour. It is here that we learn the Queen mistook a glass pool for a pool of water and lifted her skirt to keep it dry. When Solomon took a look at her legs he ungallantly remarked on their hairiness. In her 2017 exhibition ‘Bristle’ Niamh McGuinne highlighted female hairiness and ‘the idea of deviance that’s associated with it.’

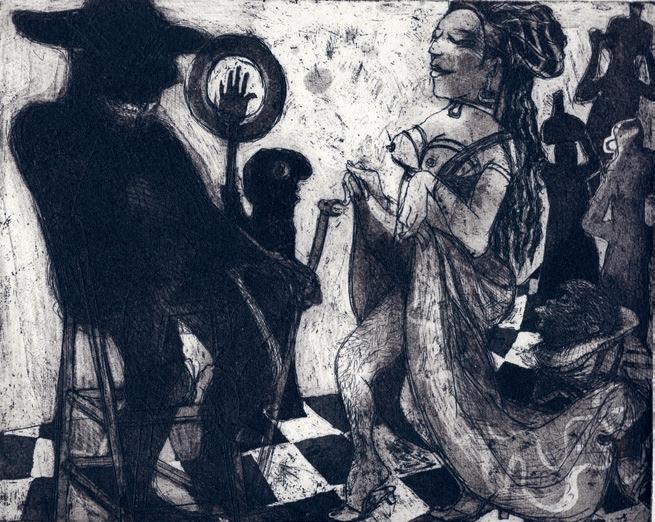

Hanselaar captures ‘the arrival of the Queen of Sheba’, but the scene is more suggestive of opera buffa than George Frideric Handel. We are to imagine ourselves standing in the throne room of Solomon’s palace, where the enlightened and all-knowing king is reduced to a dark shadow and his throne to a chair. The glass floor turns into the chequerboard of black and white marble squares which you find in 17th century Dutch interiors. The Queen, daintily lifting her skirt to reveal her hirsute legs, has a baroque feel to her as well. She has been rummaging through Rembrandt’s wardrobe of props. A small creature in a ruff bears her train. Finally, in the background on the right we see the servants carrying the gifts – a reminder of the original biblical story, which is much less visually interesting than the midrashic legend.

The Babylonian demon Lilith (‘Night Monster’) makes a brief appearance in the biblical book of Isaiah and the Dead Sea Scrolls. She occasionally appears amongst the musings of the rabbis because there are two creation stories in Genesis. If Eve is the woman in chapter 2, who is the unnamed one in chapter 1? Answer: Lilith. Her story really takes off in the apocryphal Tales of Ben Sira in the medieval period. Made from earth like Adam, she leaves him and Paradise because she refuses to lie beneath him. For this shocking lack of decorum, she is turned into a winged demon who is a danger to new-born children. The philosopher Maimonides dismissed her as a work of fiction, but she was a popular figure in Jewish folklore.

In western art Lilith has sometimes been depicted as a beautiful woman with gorgeous hair, and sometimes as a serpent, intelligent and treacherous like the snake in Eden. Hanselaar conflates these ideas in her own representation. She shows Lilith in mid-flight, with her hair streaming in the wind as clouds scud across the full moon. Around her body twines a serpent with a tail looking remarkably like a penis. This image makes me think of the portrayal of women in the painting of Franz von Stuck: particularly in ‘Sensuality’ (1891) and ‘Sin’ (1894). There is also something of the Witches’ Sabbat in this image. It is suggestive of those women who entered the nightmares of the European psyche: women who used dark forces to fly on their way to have sexual congress with Satan himself. This Queen of the Night is more sinister than the one you meet in Mozart’s ‘Magic Flute’.

Lot is a younger member of Abraham’s family. In Genesis chapter 19, Lot’s family are living amongst strangers in the city of Sodom. When Lot receives two angels as guests, the suspicious citizens of Sodom seek to rape them. To prevent this, Lot offers his virgin daughters as replacements. The angels blind the men of Sodom for their crude forgetfulness of the laws of hospitality and warn Lot of the city’s destruction. In the book of Judges there is a similar tale of a woman being used as a substitute to prevent male-on-male rape. Ken Stone remarks that, in the eyes of men within a patriarchal society, sexual violation of a woman by a man was considered less shameful than that of a man by a man.

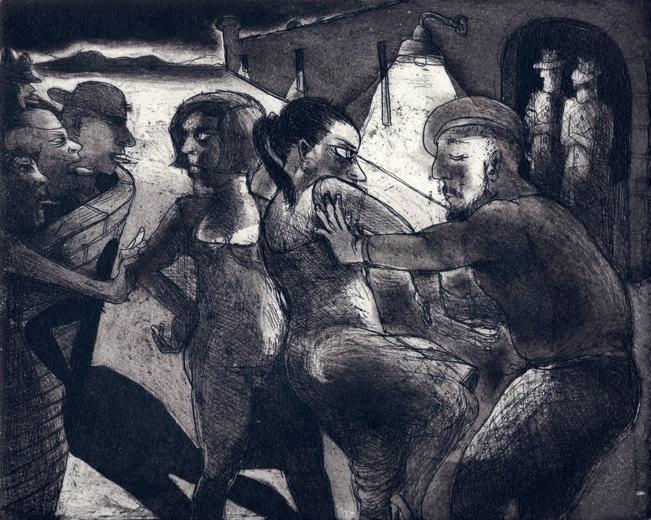

The biblical narrative emphasizes the intended ill-treatment of guests, but Hanselaar puts the emphasis firmly on Lot’s daughters. They hold centre-stage, caught between the opposing forces of their father and the men of Sodom. Their father dominates the right foreground, with his left arm stretched out, offering his daughters to the men. Behind him, lost in the shadows, are the two angels, unwitting causes of the action. On the left, the men of Sodom are situated within the safety of their city walls. They have their tongues hanging out from lust and try to touch the daughters. The body-language of the daughter on the left suggests, ‘Don’t you dare touch me’, and that of the one on the right suggests her confusion at her father’s action. Situated beyond the city walls, the angels and the family of Lot are the outsiders and seem fair game for maltreatment in a xenophobic world.

In Genesis chapter 38, Tamar’s husband dies childless. The men of his family have a ‘levirate’ duty to give him an heir. One brother performs coitus interruptus, and dies; so, his father Judah withholds the next brother and sends Tamar away, seeing her as a death-bringer. In social limbo, Tamar resorts to trickery. Sitting veiled by the roadside she lets a tipsy Judah think she is a prostitute. They have sex and she has twins. Judah seeks to burn her for adultery, but she had the forethought to take evidence of who was the daddy. Judah admits her innocence. In a later midrash, the rabbis praised the Canaanite (non-Jewish) Tamar for staying loyal to her husband and condemned the men of his family for what happened.

Dramatically, the moment when Tamar revealed her evidence and humiliated Judah could have been interesting, but not so much fun to draw as the moment of oo-la-la by the wayside. There is something bestial about the coupling as Judah takes Tamar from behind. She is the figure of whom we first become aware because her veiled faced looks towards us and away from Judah. The fury of his passionate assault is suggested by Tamar having one shoe on and one shoe off. He clasps her to himself by having one hand on her breast and another on her crotch. Meanwhile, his trousers down, she firmly clasps his naked buttocks. After all, she is not going through with this act of sexual congress for reasons of pleasure. She needs an aroused male to provide the semen which will provide the child which will give her back her social worth. Result: Tamar triumphant.

The best-known part of the story of Lot concerns his wife. She does not have a name in the Genesis narrative, although the rabbis of the Common Era called her Idit. She is portrayed by them as the opposite of her husband. Where he offers hospitality to passing strangers, she would prefer him not to. By going to her neighbours and asking for salt, she alerts them to the presence of the strangers in Sodom and thus causes the assault on Lot’s house. When the family flee the doomed city, she does not heed the divine command not to look back. For this offence she is – appropriately – turned into a pillar of salt. In the apocryphal book of Wisdom, the pillar becomes symbolic of ‘an unbelieving soul’.

Hanselaar captures the moment when Lot’s wife turns back – just before she is ‘saltified’. This is a sparsely populated plate. The 45° angle of the figures suggests the speed and the effort with which the family flees into the hills from the city of Sodom. Lot, with his baseball cap, is in the left middle ground. He is between his two daughters –who may not have very loving feelings for the man who was pimping them the day before. The main figure is in the foreground. The eyes and mouth of Lot’s wife are so expressive, as is the lifting of her left arm as if to shield her eyes from the atomicstyle blast of heat radiating from the immolated Cities of the Plain. According to one rabbinic tradition she never wanted to leave the city. Most sinister of all is the dark shadow coming in from the right… like a figure of Death, shapeless but maleficent.

The biblical book of Esther is read during the festival of Purim, which remembers the Jews’ deliverance from the genocide threatened by a Persian minister. It comes from the 4th century BCE, when Jewish communities were scattered across what is now Iraq and Iran after the Assyrians and Babylonians had destroyed the Jewish kingdoms and taken the population into exile. Hanselaar, however, does not give us the Jewish saviour, Esther, but Queen Vashti (‘Best of Women’), the first queen of King Ahasuerus. When drunk he commands her to parade her beauty before his male guests. She refused. ‘She had dignity. She had selfrespect. She said, “I’m not going to dance for you and your pals.”’ [Michelle

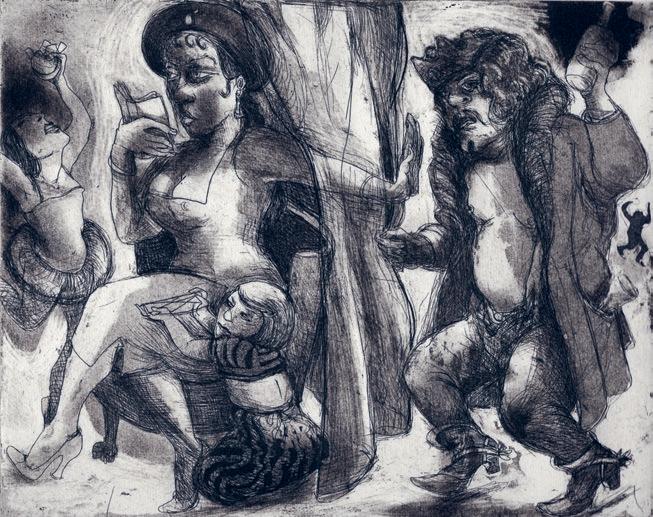

Landsberg]In Hanselaar’s image the world of men is divided from that of women by the central curtain. To the left is a self-contained world of female contentment. The kneeling servant is playing cat’s cradle whilst the queen is reading a book. On the far left a dancing girl in a tutu provides a degree of refined entertainment. To the right we have the world of men, which seems to require a boys’ own party and a lot of binge drinking. The drunken king is holding a bottle of wine and has a wine glass stuck in his pocket. He is all the more ridiculous for having knightly spurs on his feet whilst having a very open dressing gown. As he stomps in rage, he makes me think of foolish Falstaff… and even though he has the power to harm Vashti, she stands on the higher moral ground, and, in her finery and jewellery, looks far more regal than her besotted spouse.

From the 9 th century BCE and the book of 1 Kings comes the tale of Jezebel, a princess of Sidon, who marries Ahab, king of Israel. She worshipped Baal and is a hate figure in Jewish lore because she persecuted the prophets of Yahweh (i.e., their god). Ahab died in battle. Enter Jehu, devotee of Yahweh. The prophet Elisha anointed him king and Jehu exterminated the old royal family and all the worshippers of Baal. Expecting a visit from him, Jezebel adorned herself and stood by an upper window of the palace. When she taunted Jehu as a murderer, he commanded her eunuchs to cast her down. When he ordered the burial of her corpse, all that was left was her skull, hands and feet. The dogs had eaten the rest.

Hanselaar goes for maximum impact by having a close-up shot, reminiscent of a frame from a Hollywood film noir. The right half of the scene is dominated by the figure of Jezebel, with her hair piled up and her eyes lined with kohl. She is turned away from the window towards a child who acts as a witness to the proceedings. Behind the queen are two eunuchs. The one at the back, with his face half in shadow, looks particularly sinister. The one at the front dares to lay hands on the woman who was once all powerful. Her fallen state is made palpable by that one gesture. Then things get worse. As in a photograph where one exposure overlaps another, we have the ghost of things to come: Jezebel thrown to the baying dogs in the courtyard below. All the attention centres on Jezebel’s fate at the hands of her slaves. Of Jehu, there is not a sign.

Rebel Women from the Apocrypha

A series of fifteen etchings/aquatints

Plate size 20 x 25 cm

Sheet size 38 x 43 cm

Edition of 30, plus 5 APs

Printed by the artist on 300gsm Somerset paper

ISBN 978-0-9570124-4-8

Printed in 2023 by Gomer Press Ltd

Edition of 500

Published by Julian Page

For any enquiries: www.julianpage.co.uk

www.marcellehanselaar.com

There are many people I want to thank for the way they support, encourage and inspire me: my late friend Lex van Delden; my enterprising dealers Julian Page and Dirk Vonckx; the serendipity of meeting Mark Golder; my second studio, Artichoke Print Workshop; Jane Plüer for meticulous design; enduring print collector Paul Mitchell and all friends, colleagues, collectors and curators who keep me on my toes and keep the dialogue flowing.