The Future Perfect of Tinggal Kenangan

Lim Sheau Yun

It is dusk in a distant time—maybe past, maybe future. An archaeologist, surveying a gridded field, brushes away diligently at the ground. A few months ago, he excavated a terracotta brick with the word “Impian” stamped into it. The brick was broken in half, cracked down the middle. He had never been so enchanted by an object, an inert object which had awoken a private life, an object which he now understood to be charged with the mystical power of recognition. For the first time, the archaeologist considered taking home his find, a souvenir of his toil. Just for him. But he is a dutiful son, or perhaps just a coward, and he obediently brought the brick into his tent. He measured, catalogued, photographed, described. He accessioned it: “TK-Artifak-01,” also known as Batu Impian, Dream Brick.

Now, the archaeologist finds a piece of paper which contains an image. It looks like a photograph, or an impression of one, washed and metabolised into ultramarine blue. Handprints and stray marks are apparent on its bumpy surface, an unevenness pocked by the texture of paper. The people in the image are at a ceremony to pecah tanah, to break ground, too healthy and happy to be construction workers with their hoes planted demurely in the earth. The archaeologist notes that the amount of soil they have tilled with their comically large hoes is equivalent to what he would usually unearth with his hand-held trowel. In their smiles, he detects something sinister, even if plausibly benign. This is not an object he wishes to possess, but one that he fears will possess him. It is nice to think that the world is a benevolent place, but it is also silly.

After some investigation, the archaeologist recovers the dead technology that produced this image: the carbon copy. A sheet

covered with a carbon pigment was placed between two pieces of paper, where pressure exerted from the top piece was transferred through the carbon sheet, imprinting upon the bottom piece. Carbon, the elemental atom of organic life, produced an inert image of life. It was a relationship of positives and negatives: with each mark, the carbon sheet degraded, losing its potency, each further mark risking further entropic decay. He tuts at this imperfect technology, unsurprised that it was phased out, and reacts with mild surprise when he learns that an echo of the carbon copy still circulates within our digital lives: “cc,” carbon copy, “bcc,” blind carbon copy.

The archaeologist begins to understand that a carbon copy is neither forgery nor cast, but rather an inconsistent encounter between pressure, the printed surface, and the fickle, oversensitive mediator of the carbon sheet. It is not carbon suspended in smooth gelatine film, as in some forms of photography, but rather an outcome radically contingent upon the objective, textual nature of the printed surface. It produces an ambivalent middle between surface and object, a processed image that it is distinct from the original, natally connected to but umbilically severed from the reference surface. What the carbon copy delivers is an impure view of reality, one that makes the archaeologist question the very purity of the photograph itself.

If the medium is the message, intelligence is artificial, and machines are running on empty, then the object-as-multiple functions as an avatar, making things more true, more real, more felt, more profoundly banal, more profound in their banality. There is no overwhelming force quite like time when algorithms generate in nanoseconds, each refresh bringing a fresh deluge of image and information. To proliferate is to remain present, to be recalled if not remembered. The timbre of authorship is just another relic of the past. In a networked age, nothing exists in or for itself. Slowly, carbon copies accumulate in the archaeologist’s archive. There is a stamp, there is another photograph, there are organisational charts and maps of hierarchy. The archaeologist’s memory, or more precisely his awareness of his present, is beginning to fail him. He knows that the public collection is the antithesis of

the private souvenir, and he contributes what he can to a digital repository which he hopes will live beyond his lifetime, will live on forever. In his dreams one night, he sees his archive—a behemoth of a spreadsheet—decay like a falling tower of bricks. He can’t remember, no one remembers. The carbon copy remembers, imperfectly. When he wakes, he gets back to work excavating the remains of Taman Kenangan. Location: Gunung Ledang, Johor.

Izat Arif ’s three-part exhibition series Taman Kenangan (Nostalgia Park) pulls apart the past and the future and examines its sinewy tissue. Taman Kenangan is a fictional site, set in Johor’s Gunung Ledang, that serves as metonymy for all lands of promise in the Malaysian imagination. It is Gunung Ledang, but it is also Bandar Baru Bangi,1 it is Shah Alam, it is Desa Park City, it is Wawasan 2020, it is Malacca, it is Kuala Kangsar, it is the Federal Land Development Authority (FELDA). The first edition of Taman Kenangan began in 2019 as a project to commodify the past at a state level, executing with sovereign authority the fantasies of an architect-bureaucrat longing for a new architecture to redeem an idyllic past. The series’ second edition, Kenangan itu hanya mainan bagimu… (These memories are just a game to you…), embraced the utopic poetics of a real-estate agent, exhibiting a sales gallery whose central object was a diorama of a Gunung Ledang covered in scaffolding. Whether the mountain was under construction, or was being held up against erosion, one could not be sure. Tinggal Kenangan (Ruins of Memory), the last edition of Taman Kenangan, figures itself around an archaeologist who has discovered the lost site of Taman Kenangan. It is the final, wistful reflection of a project about nostalgia.

In Taman Kenangan, Izat instrumentalises roleplay to ape agents of authority: in the first edition, the state, in the second, the corporation, and finally, with Tinggal Kenangan, the disciplines of knowledge that uphold power and authority. It is not a mere

1 See more on Bangi in Tan Zi Hao’s essay in this book, “Living Ruined Dreams: Being Modern and Moderate in Post-Mahathirist Time,” 14-27.

case of “knowledge is power,” wherein knowledge is an instrument of power. Instead, power uses, reproduces, and shapes knowledge; and conversely, knowledge is capable of investing power with the authority of truth. For the philosopher Michel Foucault, power and knowledge were so mutual, inseparable, and symbiotic that they were always hyphenated: power-knowledge. “Between techniques of knowledge and strategies of power,” he writes, “there is no exteriority, even if they have specific roles and are linked together on the basis of their difference.”2 The goals of power and the goals of knowledge cannot be autonomous: in knowing we have power, and in having power we know.

It is from within the power-knowledge matrix that Izat invokes his subversive strategy of sindiran, an insinuative, satirical mode of figurative speech inspired by his grandmother’s delivery of veiled criticism. Izat’s sindiran owes its humour to a postmodern pastiche. Confabulating context, mood, and tone, he draws upon imagery from middle-class ersatz aestheticism: Roman columns, batik prints on linoleum, millennial houseplants, the religiouscapitalist complex. Yet as he directs his sindiran at outward targets, his critiques inevitably implicate himself. He comes from and is part of the very matrix he pokes fun at. The nostalgia in Taman Kenangan is not a yearning for the idyllic past, but rather a nostalgia for an impossible outside, a place of “anti and nonauthority”3 where utopia is possible, and we can be free from the powers-that-be.

Kuning Ledang bagai dikarang, Riang-riang disambar wakab; Hairan memandang dunia sekarang, Bayang-bayang hendak ditangkap.

- Sulalutus Salatin

Yellow Ledang, so finely spun, In joy struck by a soaring eagle; Strange to see the world today, Where men seek to capture shadows.

2 Michel Foucault, History of Sexuality Volume I (New York: Random House, 1978), 98.

3 Susan Stewart, On Longing (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1993), xiii.

In Sulalutus Salatin (Sejarah Melayu/The Malay Annals), Sultan Mansur Shah, the Raja of Malacca, declared that he would have a wife to surpass any other in the world. Never mind that he was already married to a princess of Java and a princess of China. He wanted a wife who was otherworldly, a wife beyond humanity, a wife that no other Raja could possess. He decided that he would wed Puteri Gunung Ledang, the Fairy Princess of Mount Ophir. The Sultan would have mastery over all realms: domestic, foreign, and supernatural alike.

The Sultan dispatched his now elderly servant, Hang Tuah, and a retinue of other captains to meet with the Puteri. They began a perilous climb: as they ascended, they were met with gusts of raging wind. Hang Tuah could go no further, instead, his captain Tun Mamat continued in his stead. Tun Mamat braved the winds and passed through a thicket of singing bamboo until he reached an altitude where the clouds were almost within reach. Finally, the trees parted, and there he found four women in a garden of splendour, and he relayed the Sultan’s proposal.

Later that night, an old woman appeared like an apparition in front of Tun Mamat. She told him the Puteri’s desired betrothal gift: a bridge of silver and a bridge of gold from Malacca to Gunung Ledang seven trays of mosquito hearts, seven trays of mite hearts, a vat of water from dried areca nuts, a vat of the tears of virgin maidens, a cup of the Sultan’s blood, and a cup of the Sultan’s son’s blood. And above all, she wanted a cup of the Sultan’s son’s, the Raja Muda’s, blood.

In the time of Taman Kenangan, Gunung Ledang has been turned into a real estate project. With the advent of this modern development, Puteri Gunung Ledang has supersized her demands to the scale of industry. Her demands shall thus be fulfilled with an equipotent tool of production: the factory.

While still warm, mosquitos and mites, like precious ore, are received by sorting machines, and the enormous arms of a robotic controller, punctuated by nanoscopic surgical instruments,

perform arthroscopic operations to harvest their hearts. Workers live-work-play in a nearby industrial park, lest they stray too far from their labour. An intravenous drip begins from the Raja Muda’s desiccated arm and multiplies, growing thicker and larger and more numerous until the drip becomes a network of drains in a densifying suburb, carrying his blood from the royal palace through a makam serbaguna, a multi-purpose tomb where blessings are automated and prostration is programmed, terminating in a vat for stowage. There, the vats await fulfilment. Yang Bertakung, Yang Tertakung Dan Yang

Menakung Di Dalam Takungan. The stagnant, the stagnated, and those stagnating within stagnation.

In the middle sits a construction site, a permanently temporary place rendered into stillness. When the building appears, the construction site disappears. Built to expire, a middling condition is the organising metaphor for Taman Kenangan: a middle state in middle Malaysia for the middle income middle class. The middle arrests the past and future, but is obsessed with where it come from and it is going. Hence, the twin flames of the suburban imagination: nostalgia and technology.4

Search term: Future perfect tense

Definition: A future action that will have happened by a certain time in the future. This tense also expresses predictions or suppositions about what may have happened in the past.

Example: “I’ll have remembered.” “I won’t have remembered.”

Time will have become all muddled for the archaeologist. Years and dates will remain crystal in his mind, but time will feel have felt like a humid cloud that envelopes him, rendering the air thick and world blurry, as if experienced through the loose gestures of an untuned analogue clock. He will have spent his days surveying,

4 Stewart, On Longing, 1.

drawing, making dioramas, searching for a visible image of that deep, dark, bottomless image of the past.

The year will be 1968. A magazine will have been circulated to all the new landowners under the Federal Land Development Authority. On the cover, it will have said, No need to be poor. Soon, the kampung will have been turned into a plantation, its borders circumscribing the newest land of promise.

The year will be 1997. An eleven-year-old Izat Arif will have rediscovered his homeland through the utopian township of Bandar Baru Bangi. Everyone will have been talking about the impending financial crisis. Never mind burst bubbles—he will be far more concerned about burst pipes.

The year will be 2024. An archaeologist will have had an exhibition. The archaeologist will have seen, carbon-copied onto a wall, a photograph of coconut trees, blurred as if gleaned from an accelerated car on a highway. Every drawing, every object, every exhibition is but a miniature of a realisable world we seek to model and export. It is a closed space in an open time.

The year will be 2024. An artist will have had an exhibition at a gallery called A+ Works of Art. He will have been selling peninggalan kenangan, the remainders of memories.

Tinggal kenangan, gagal segala impian

Tinggal bertanya arti sejati

Kenangan itu hanya mainan bagimu

Tinggal bertanya arti sejati

Yang telah engkau janjikan dulu, oh - “Sejati,” by Wings (1990)

Kalau Hendak Kenal Pokok, Tengok-lah Buah-Nya, Kalau Sakit Belakang, Tanyalah Datuk Kau.

To know a tree, its fruit you must see, If your back aches sore, go ask your grandfather.

Graphite on paper, 113 x 145 cm, 2024

Mulut

Sweet are your words, but you leave nothing but bile.

Graphite on paper, 113 x 145 cm, 2024

Manisnya

Tuan, Yang Ditinggal Hanya Hempedu.

Yang Bertakung, Yang Tertakung Dan Yang Menakung Di Dalam Takungan.

The stagnant, the stagnated, and those stagnating within stagnation.

Graphite and acrylic on paper, 113 x 145 cm, 2024

Notes For Drawing 4 Ink on paper, 21 x 28.6 cm, 2024

Ubati Rindu Dengan Kenangan Lalu, Ubati Pilu Dengan Air Mata. Heal longing with memories past, mend sorrow with tears shed.

Graphite on paper, 113 x 145 cm, 2024

Pujalah Di Siang Hari, Malam Tak Ada Yang Menanti. Offer your praise in daylight, by night, no one waits for you.

Graphite on paper, 113 x 145 cm, 2024

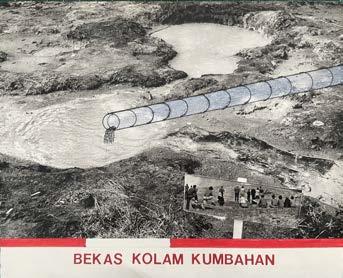

Kenangan Longkang 1

Drain Memories 1

Acrylic on photograph, 16.9 x 16.5 cm, 2024

Kenangan Longkang 2

Drain Memories 2

Acrylic on photograph, 16.6 x 20 cm, 2024

Kenangan Longkang 4

Drain Memories 4

Acrylic on photograph, 26 x 20 cm, 2024

Kenangan Longkang 3

Drain Memories 3

Acrylic on photograph, 11.3 x 10.2 cm, 2024

Kenangan Longkang 5

Drain Memories 5

Collage, acrylic, ink and vinyl sticker on photograph, 16.6 x 20 cm, 2024

Scaffolding & Gunung Ledang

Ink on paper, 21 x 14.3 cm, 2024

Sempadan & Deco

Ink, graphite, correction liquid, and marker on paper, 21 x 14.3 cm, 2024

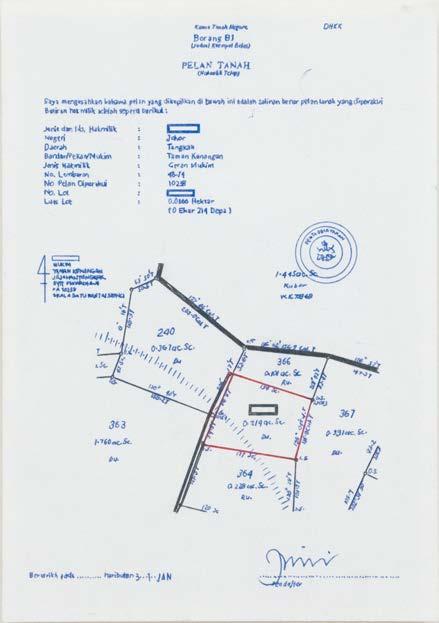

Land Plan

Carbon copy, ink on paper, 29.7 x 21 cm, 2024

Pelan Tanah

Pecah Tanah 1

Ritual 1

Carbon copy on paper, 29.7 x 42 cm, 2024

Pecah Tanah 2

Ritual 2

Carbon copy on paper, 29.7 x 42 cm, 2024

No Need To Be Poor

Carbon copy on paper, 42.7 x 42.7 cm, 2024

Carta Organisasi Pejabat Pengurusan Taman Kenangan Taman Kenangan Management Office Organizational Chart

Carbon copy, ink on paper, 59.4 x 84.1 cm, 2024

Taman Kenangan Happiness & Wellbeing Committee

Graphite, ink, highlighter on paper, 59.4 x 84.1 cm, 2024

Jawatankuasa Kebahagian & Kesejahteraan Taman Kenangan

TK Promo 1

Collage and vinyl sticker on paper, 31 x 21.5 cm, 2019

TK Promo 2

Collage and vinyl sticker on paper, 30 x 23 cm, 2019

TK Promo 3

Collage and vinyl sticker on paper, 31 x 21.5 cm, 2019

Single channel video with audio on loop, 6:20 mins, 2024

Stills from Retak Seribu Impian Di Taman Kenangan

Taman Kenangan: A Thousand Shattered Dreams

Batu Impian (TK-Artifak-01)

Dream Brick (TK-Artifak-01)

Terracotta, marine plywood, steel fixtures and foam, 103 x 48 x 24 cm, 2024

◀︎ Close up image of artwork installation

Membilang Kenangan Yang Abadi, Seperti Menunggu Mentari Senja. (TK-Artifak-02)

We count our eternal memories, As a twilight sun slips into the dark (TK-Artifak-02)

Carved Balau wood coconut, plywood, steel fixtures, foam, 123 x 60 x 34.5 cm, 2024

◀︎ Close up image of artwork installation

Kenangan Itu, Hanya Mainan Bagimu... 0.5 (TK-Artifak-03)

These Memories Are Just A Game To You... 0.5 (TK-Artifak-03)

3D print, soil, plaster, model foliage, industrial paint and marine plywood, 113 x 44.5 x 37.5 cm, 2020

◀︎ Close up image of artwork installation

Alat-Alat Kebesaran Koprat (TK-Artifak-04)

Corporate Regalia (TK-Artifak-04)

Ball Pen, Lanyard, Card Holder, Desk Organizer, Post It Notes, Ceramic Mug, Marine Plywood and Transparent Sticker, 62 x 135 x 30 cm, 2024

Mahligai Impian

Dream Palace

Terracotta bricks on painted marine plywood pallet, 95 cm x 120 x 140 cm, 2024

Oh, Kenangan, Tinggallah Kenangan...

Oh Memories, Only Memories Remain...

Found images, industrial paint, soil, plaster, corrugated metal, stone and wood, 45.7 x 45.7 x 30.5 cm, 2024

Engkau Pergi, Telah Ditakdirkan...

You Were Destined To Go...

Found images, industrial paint, soil, plaster, corrugated metal, stone and wood, 45.7 x 45.7 x 30.5 cm, 2024

Peta Kerja2 Taman Kenangan Map of Taman Kenangan Works

Paper, wood, marker, vinyl sticker, aluminium rod and glass, 81 x 61 cm, 2024

Installation view of artwork ►

Installation view of Suasana Taman Kenangan

Atmosphere of Taman Kenangan

Carbon copy, painted scale rulers, foldable ruler, and steel stake on wall, 162 x 500 x 2 cm, 2024

Installation view of Tinggal Kenangan

Installation views of Tinggal Kenangan

Installation view of Tinggal Kenangan

Close up image of artwork ►

Yang Bertakung, Yang Tertakung Dan Yang Menakung Di Dalam Takungan. The stagnant, the stagnated, and those stagnating within stagnation.

Installation view of Tinggal Kenangan