14 minute read

OFFSHORE AQUACULTURE

OFFSHORE AQUACULTURE Science-deniers and the global ecological crisis

By Neil Anthony Sims*

There is a global ecological crisis, driven by humanity’s ongoing heedlessness that needs collective, concerted engagement, if we are to avoid the planetary-scale consequences. The United Nations has convened panels of expert scientists to plot a path forward, out of the quagmire, and their conclusions are unequivocal: we need significant changes in policy, supported by radical reinvention of how we do business, and we need all of this to happen quickly.

Yet in the face of this imperative, there are powerful, vocal groups who continue to rail against the expert-recommended innovations and policy changes. These groups willfully choose to ignore the science, and instead bleat platitudes and promote patent falsehoods, muddying the issues and fostering fear mongering. The consequences of such denial of the science are very real, and will be manifested in ongoing human health costs, and an altogether avoidable ecological catastrophe. We bring this on our own heads – or rather, it is brought upon us by those who continue to deny the preponderance of scientific evidence.

This all sounds too familiar: the onslaught of obfuscation from the global climate deniers, right? Yes, but we aren’t just talking about fossil

fuels and carbon. This scenario also describes the global seafood crisis, the ocean’s potential to mitigate climate change impacts, and the resistance to policy change from the anti-aquaculture advocates. There are now compelling conclusions, from global leaders in their respective fields of study, that urge a transition from our reliance on terrestrial agriculture to more marine based food production. It is clear: we need more marine aquaculture! There is also now abundant research that demonstrates that in deep water, further from shore, the environmental impacts from responsibly farmed fish are minimal, if detectible at all. Yet, still, the anti-aquaculture activists persist; their heated handwringing, inflammatory innuendoes and flatout falsehoods pile up like bloated carcasses on a beach.

No less an august body than the United Nations High Level Panel on Climate and Oceans has delivered a report entitled “The Ocean as a Solution to Climate Change”, which makes five recommendations, or “Opportunities for Action”. Of these five, the opportunity for “Fisheries, Aquaculture, and Dietary Shifts” argues that we must “Shift (human) diets toward low carbon marine sources such as sustainably harvested fish, seaweed, and kelp as a replacement for emissions from intensive land-based sources of protein.” (Back when I was in school, kelp was a seaweed, but never mind … we will forgive them that redundancy).

The UN HLP report also establishes medium-term goals, (i.e. a target date of implementation by 2025), of creating “incentives to switch from high-carbon land-based sources of protein to low-carbon

ocean-based sources”, and goes so boldly as to “explore potential impact of a carbon tax on red meat and other carbon intensive food”. Wow! In case there was any doubt as to what we should be eating, the final medium-term goal is to “develop and bring to scale high-technology digital aquaculture”. That, friends, is us – the world needs offshore aquaculture!

The Expert Group was cochaired by Oregon State University’s Dr Jane Lubchenko, previously head of NOAA under the Obama administration. Dr Lubchenko is a renowned marine conservationist. The Expert Group also included other luminaries from the ocean conservation and global climate fields, such as Dr Steve Gaines of UCSB’s Bren School, Dr Rashid Sumaila of University of British Columbia’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, and Dr Ove Hoegh-Guldberg of the University of Queensland’s Global Change Institute. These folk carry considerable gravitas in the conservation community. They are not known for giddy arm-waving. It is hard to dismiss their conclusions.

Yet, in spite of this preponderance of science, Canada’s new government continues to move forward with a plan to end open water net pen fish farming in British Columbia, though strangely, not in the Atlantic Maritime provinces. There is perhaps irony that Canada’s Prime Minister is also a member of the High Level Panel on Oceans. (Notably, however, Canada did not sign the “Call to Ocean-Based Climate Action” that the Panel issued during the course of the recent national election). The Canadian government’s plan is to move all B.C. salmon farming from net pens to land-based recirculating farms. This certainly limits the economic scalability of the industry and the affordability of the product to consumers: it increases the capital equipment and operating costs, as well as the GHG impacts from energy use. More expensive salmon would certainly not encourage more seafood consumption. People will presumably, then, just eat more beef. This is aligned with neither the UN High Level Panel’s recommendations, nor with the earth’s best interests.

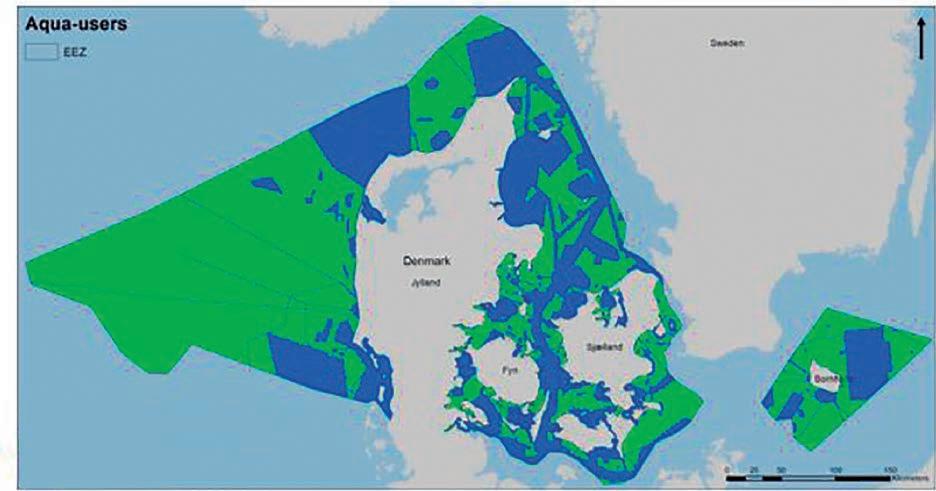

Denmark has also recently called for a moratorium on expansion of marine fish farming. This has been gleefully miss portrayed by antiaquaculture activists as the shutting down of all net pen production in Danish waters, but is actually a recognition by the government that the country’s EEZ may have reached its carrying capacity. The government

Danish EEZ waters that are currently committed for other uses (shown in blue), or that are not currently committed and could be suitable for aquaculture (shown in green).

has simply stated that there will be no development of any new seabased fish farms or expansion of any of the 19 existing farms.

Danish Environment Minister Lea Wermelin declared that ‘Denmark has reached the limit of how many fish can be farmed at sea without risking the environment”, and suggested that expansion of marine fish production should be confined to onshore developments.

“We have major challenges with oxygen deficiencies, and we can see that nitrogen emissions are not falling as expected. Therefore, it is the government’s position that there is no room for more or larger facilities in Denmark,” said Wermelin.

At least these conclusions would seem to be based in science, and that is to be applauded. Given that most of Denmark’s marine farming is currently located in the shallower, more protected waters between Denmark and Sweden (see Figure 1); some prudence would not seem misplaced. And Denmark is already the eighth largest producer of farmed marine fish in the EU.

However, there is ample ocean space in Denmark’s EEZ in deeper water to the west. Yes, certainly, this is fully exposed to the North Sea, but Norway and China are already launching offshore net pens that are designed to withstand North Sea storms or South China Sea typhoons. Denmark’s government would seem to be perhaps flinching in the face of a challenge, by essentially stating up front “No, we aren’t going there”. Perhaps if they read the UN HLP report, they may reconsider.

In the U.S., meanwhile, the AQUAA Act (“Advancing the Quality and Understanding of American Aquaculture”) creeps forward through the jungle that is the Congressional legislative process. This legislation would provide clarity for offshore aquaculture regulation in U.S. Federal waters, as well as considerable financial support for offshore R&D. In March, Representatives Peterson (Democrat, Minnesota) and Palazzo (Republican, Mississippi) co-introduced H.R. 6191 into the House of Representatives. This bill parallels closely the Wicker Bill that had previously been introduced into the Senate.

So, we wait in hope for Congressional wheels to turn. Or … perhaps not. Waiting is not what the UN HLP has urged us to do.

The U.S. Constitution is a beautiful document, and its 10th Amendment is outright exhilarating. To wit: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” Paraphrasing loosely, this means that you don’t need permission from the legislature or from the executive branch to grow fish in the ocean, so long as there is no law against it. Until the AQUAA Act is passed and signed, there is no such law. (Well, some of us would have been happy to have offshore aquaculture administered under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Management and Conservation Act – the law which governs all other living marine resources in Federal Waters – but some fringe fanatics sued to prevent NOAA from implementing their Management Plan).

There is still a multitude of Federal and State permits that are yet required to deploy even a small, temporary net pen in Federal waters. Ocean Era (formerly Kampachi Farms, LLC) therefore continues to pursue the permits for a demonstration net pen in Gulf of Mexico waters, some 40 nautical miles offshore from Sarasota, Florida. The “Velella Epsilon” project is largely supported by NOAA’s National SeaGrant Program, and is primarily designed to allow the Florida fishing

and boating community to learn to appreciate the positive benefits that can flow from offshore aquaculture.

The premise is founded on the company’s prior experience with the Velella Beta-test and the Velella Gamma-test projects, which floated a small (20 ft diameter) Aquapod as, firstly, an untethered, free-drifting array, and then as a feed-barge and net-pen on a single-point mooring some 6 miles (10 km) offshore of Kona, Hawaii. These projects pioneered the permitting process for offshore aquaculture in Federal waters with both NOAA and US Army Corps of Engineers. They were also instructive biologically: performance of the 2,000 Seriola rivoliana, or kampachi, that were stocked into the Velella’s Aquapod was phenomenal. Growth rates, feed conversion ratios (FCRs), and survival rates far exceeded that recorded from other offshore net pens for this species. The projects also developed remote command-and-control technologies connected through a wireless bridge to shore, and thence to the cloud, that allowed for the fish to be fed and monitored from anywhere in the world with a smart phone and Wi-Fi connection.

However, the truly revelatory finding from these two projects was the enthusiastic response from the

Fishing boats gathered around the Velella Beta test net pen array, offshore of Kona, Hawaii. The vessel in the foreground is the S.S. Machias – the tender vessel that was attached to the Aquapod net pen. This “drifter-cage” net pen aggregated tuna, marlin, mahimahi and wahoo, and was exceedingly popular with local recreational, commercial and charter-boat vessels. Photo credit: Ocean Era, LLC.

Figure 3

Fishing boats gathered around the Velella Gamma test net pen array, offshore of Kona, Hawaii, as viewed from the M.V. Ekolu – the remote-controlled, unmanned feed barge. The Gamma test array also aggregated pelagic sportfish and food fish, but was even more popular with the local fishing community, as it was moored on a single-point mooring, in 2,000 m of water, and its location was more predictable than the “drifter cage” of the Velella Beta-test. Photo credit: Ocean Era, LLC.

In the U.S paraphrasing loosely the constitution, it says that you don’t need permission from the legislature or from the executive branch to grow fish in the ocean, so long as there is no law against it.

local recreational, commercial, and charter-boat fishing community, who found the offshore net pen arrays acted as stupendous Fish Aggregating Devices, or FADs. Tuna, marlin, mahimahi, and wahoo could be caught in abundance around the Velella arrays. One Kona fisherman exalted that “this was the best fishing that I have had in my life!” (See Figures 2 and 3).

Fishermen are notoriously skeptical of the stories that others might tell - there’s a reason that an exaggeration is sometimes referred to as a ‘big fish story’. And so, rather

Figure 4

The Velella Epsilon Project is a proposed demonstration net pen on a swivel-point mooring, to be located ~ 40 Nm offshore of Sarasota, Florida, in 40 m (130 ft) deep water, over a soft sand substrate. The project is designed to demonstrate the benefits of offshore aquaculture to the Florida fishing community. The proposal is already popular with commercial and charter-boat fishermen.

than sharing in words and pictures the benefits of offshore net pens in Kona, the Velella Epsilon was designed to offer first-hand experience for the Florida fishing community, to turn them into offshore aquaculture advocates.

The best available science indicates that 20,000 fish, in a net pen in 40 m deep water, located 40 miles offshore (Figure 4), will have no significant effect on water quality or the soft substrate beneath the pen. Most likely, the impacts on water quality will not even be detectible. The proposed mooring design – a swivelpoint mooring – would even further reduce any potential impacts to the substrate. The Gulf of Mexico Fisheries Management Council – the ostensible voice of commercial fishing consensus in the Gulf - gave cautious approval for the project. Commercial fishermen from Florida’s Gulf Coast have also expressed keen interest in involvement in the project, by leasing boats, wharf space, or processing plants. The management from the Southern Shrimpers’ Alliance helped vet the location of the proposed mooring for the array, to ensure that it was not located in any shrimp trawl grounds. Local charter-boat fishermen and fishing guides have written enthusiastic, supportive letters, recognizing the potential FAD benefits of the project.

In spite of this evidence, and these efforts, the usual fringe antiaquaculture activists arose to oppose the Velella Epsilon project. This was much as expected; they have opposed pretty much every other offshore aquaculture project that was ever proposed in U.S. waters, out of principle. (Such said ‘principle’ being: they detest the very notion of growing fish in the ocean, and will not be swayed by any evidence that might erode their hard-held opinions, no matter how sound the science or respected the scientists. “Facts, be damned!” they seem to say. “We have attitude on our side!”).

It was, however, deeply disappointing that several so-called “environmental” groups – entities that might have otherwise laid claim to being guided by science, such as Friends of the Earth and the Sierra Club - have joined the naysayers. Ignoring all of the above evidence, they have dug deeper into the darkness of science denial. And so the public hearing to accept comments on the EPA’s NPDES permit for the Velella Epsilon was enlivened by protestors dressed as dolphins, and a rowdy crowd waving “Not here! Not now!” signs with a slash through an image of a fish. (If not here, not now, then – pray tell – where and when?!).

The Sarasota City Commissioners voted to also send a letter of condemnation of the project to EPA, highlighting the concern that these 20,000 fish could exacerbate the red tides that have been decimating sea life along Florida’s Gulf

Coast in recent years. Never mind that red tides also kill farmed fish. Never mind that the best available science indicates that Florida’s red tides are caused by nutrients almost entirely of terrestrial origin (municipal wastewater treatment and agricultural run-off), which are concentrated along the shoreline by the shallow water and minimal currents. Never mind that the selected site is 40 miles away from the shoreline, in waters over 40 m deep. The City Commissioners neither paid any heed to the scientists, nor accepted an offer to hear from the project proponents. Science, clearly, was not needed here.

So Ocean Era waits in hope, with eager anticipation, but no expectation Offshore fish farmers are genetically predisposed to optimism, but this is also usually tempered by experience, to a cautious pragmatism.

If the Velella Epsilon permits are issued, then the company will need

about 6 to 8 months to mobilize, deploy, and stock the net pen. If the permit is denied, then we – all of us – will have to ponder deeply the role of science, and the costs of fear mongering, in shaping public policy, and our planet’s future.

Neil Anthony Sims is co-Founder and CEO of Kampachi

Farms, LLC, based in Kona, Hawaii, and in La Paz, Mexico. He’s also the founding President of the Ocean Stewards Institute, and sits on the Steering Committee for the Seriola-Cobia Aquaculture Dialogue and the Technical Advisory Group for the WWF-sponsored Aquaculture Stewardship Council.