4 minute read

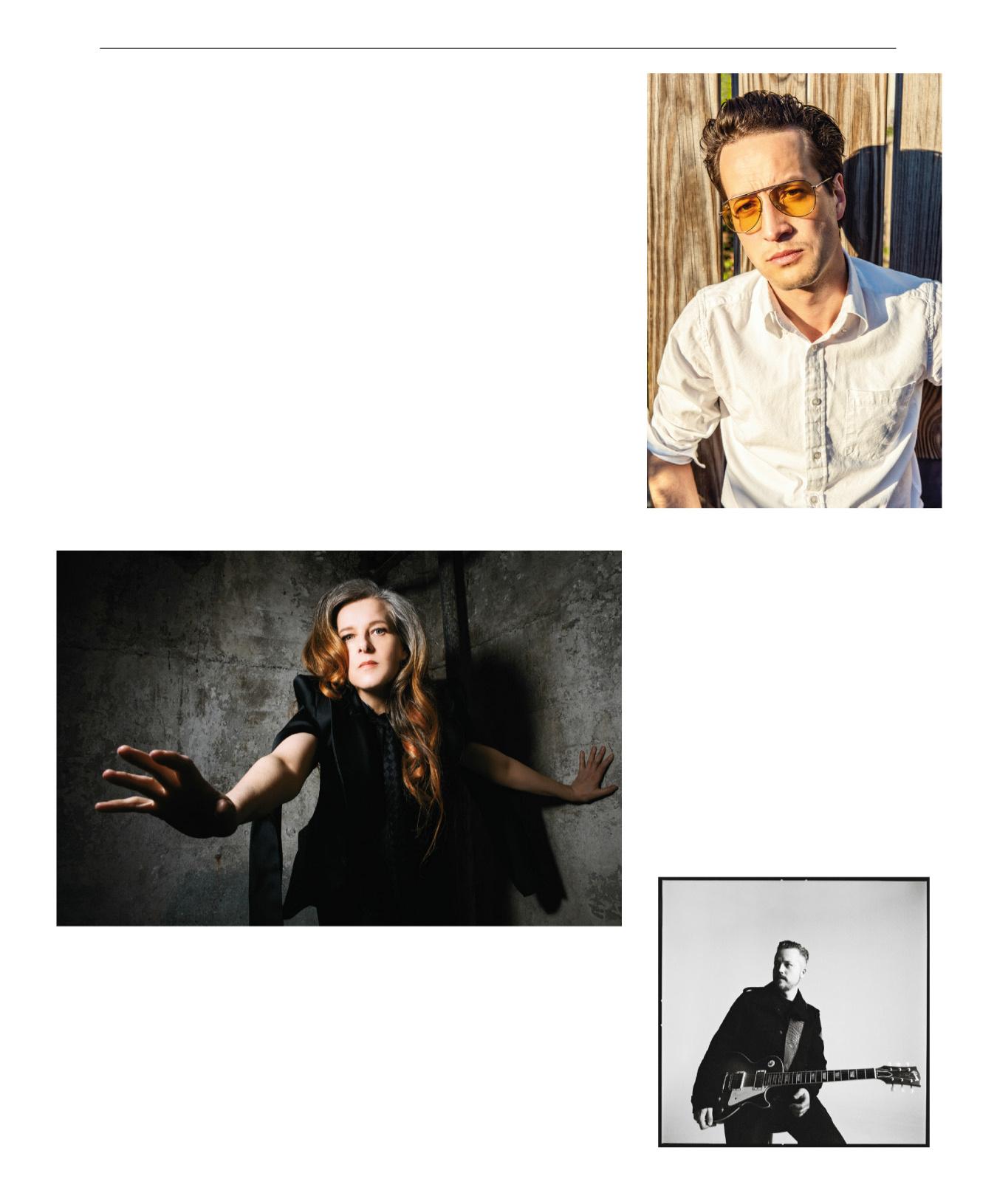

Maya Hawke, Marlon Williams, Jason Isbell, Mckenna Grace, and Neko Case

from redunradar_2023

by aquiaqui33

crime limited series Friend of the Family, which co-stars Anna Paquin (X-Men), Jake Lacy (The White Lotus), and Colin Hanks (The Offer, the Fargo TV series). Rather that lounge in her trailer between takes, Grace says: “Whenever inspiration strikes, I write. I’ll always bring an instrument to set. And Colin has this huge ukulele in a holder next to his chair. Sometimes I’ll get inspired and start strumming!” Grace says both music and acting are “like therapy. It’s very, very nice to go on set and spend a day crying, getting all the emotions out. Music is a different therapy, because I’m writing it all out. In music I’ll discover: ‘Oh, this is why I felt that way.’” Maya Hawke—a 24-year-old rising star that broke through this summer as a Stranger Things co-star and for her critically praised album MOSS— says acting and music “affect my life differently. I have more independence and control in my music. And music is generally a bit faster—maybe a two week run, where we’ll [her collaborators and producer] work all day long.” For movies and TV, however, require “waiting in your trailer, waiting in auditions to be chosen. But both movies and music are about communication and telling a story.” Hawke, the daughter of established actors Ethan Hawke and Uma Thurman, has also been working with Bradley Cooper, co-starring in the upcoming Leonard Bernstein biopic, Maestro, which Cooper again both directs and stars in. Oldham also fnds acting and music to be for veteran singer Candi Staton, and Oldham found that, “Yeah, my brain was just waiting for that assignment. Also, in another way I was making music for somebody else. Of course I did have to adhere to my own codes of quality, but I mostly needed to satisfy the demands of what Candi, as a recording artist, might be able to use. So submitting myself to a flmmaker can be quite liberating.” However, Oldham diverges from Grace and Hawke’s fuency in both music and streaming series. He far prefers flm for acting, even though its opportunities appear to be dwindling in this period of pandemic-box offce returns and TV series inundation. “It’s funny, and I don’t mean ‘ha ha,’ that movies were a medium created for a certain kind of experience, a certain kind of practical display, that just doesn’t exist anymore. Because movie theatres are, for the most part, garbage. And that’s what the medium was created for. And people don’t go to them, except for big amusement park ride movies. So the idea that cinema, as far as I understand it, is kind of dead, because the movie business is driven by things that are so alien. As a kid I thought acting was the thing to do. And I don’t recognize anything that I call acting in most movies now. It’s people staying physically ft so they can stand on green screens stages for hours a day for months at a time.” Marlon Williams

as much of a red tape free life as possible. Crews are massive! Budgets are huge! And the money’s being spent on, what? Nothing related to what you see onscreen, I think.” Fortunately, Bonnie “Prince” Billy is more upbeat about the future for musicians like himself. Oldham admits: “It’s kind of universal in print and fction writing, in music, and in flm—just understanding the relationship between creator and audience, as things have shifted so considerably over the past 10 or 15 years. It’s frustrating.” However, as Oldham began a slow post-peak-pandemic return to “touring, and having dialogues with other people along the way. It has been truly exciting. So I’m optimistic that things are happening that can’t be quantifed or even described by my experience of online worlds. Or journalistically nurtured perceptions. Things that are happening person to person and community to community are really happening. And the only way to witness it is to participate and experience it. So yeah, music is pretty great right now.”

Advertisement

fulflling in different ways, and loves how one affected the other while he worked on the fawned-for indie Old Joy, released in 2006. Because “the vision, for lack of a better word, was in that case in director Kelly Reichardt’s hands. And my brain doesn’t need to keep track of anything except my character, and my relationship with Kelly and the rest of the crew. Which leaves a signifcant portion of my brain free to do things that it often times doesn’t get to do. And I didn’t know what I was going to do with that.” His mind wasn’t idle for long, thankfully. During the flming of Old Joy, his friend, the recording engineer and producer Mark Nevers, asked him write a song Neko Case

Oldham adds that prestige TV isn’t flling that void for him, despite the hype. As a co-star of Old Joy, he needed only to communicate with seven or eight collaborators between his castmate Daniel London, Reichardt, and the crew. There were more people bogging down the email thread for a recent animated series he lent his voice to—assistants and assistants of assistants CC’d the joy out of his creative process. Even more byzantine bureaucracy led him to walk away from a series he was cast in—he raises his hands in quavering indignation next to his head while recalling the copious emails that “had nothing to do with the work. I like to have