Architecture

PRACTICE AND MATERIALITY

Bulletin VOL 79 / No. 2 / DECEMBER 2022

2022 NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARD WINNERS

Recognising the diversity of talent across the built environment

FOREWOR d 04

Laura Cockburn

E d ITORIAL 05

Kate Concannon

PRACTICE ANd mATERIALITy 08

Opportunity for practice Words: Cate Cowlishaw 12

Practising in strange times Words: David Welsh 14

Changed approaches to working Words: Chris Bosse 16

Better together: starting a practice and a family at the same time Words: Steani Cilliers and Chris Mullaney 18

Growth through uncertainty People-centred practice Words: Steven Donaghey 20

The value of people in practice Words: Amy Dowse 22

The cost of caring Words: Byron Kinnaird and Liz Battiston 24

Scrolling past complacency: a new generation of discourse Words: Elsa Ya Shi Baker 26 The unnaturally shrinking profession Words: Kerwin Datu 28

Pursuing public works A Conversation with Callantha Brigham, Andy Fergus and Timothy Moore

ARCHITECTURE BULLETIN

VOL 79 / NO 2 / dECEmBER 2022 Official journal of the NSW Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects since 1944.

30

Is the competitive design process anti-competitive? Words: Matilda Gollan 32

A letter to competitions Words: Matt Chan 35

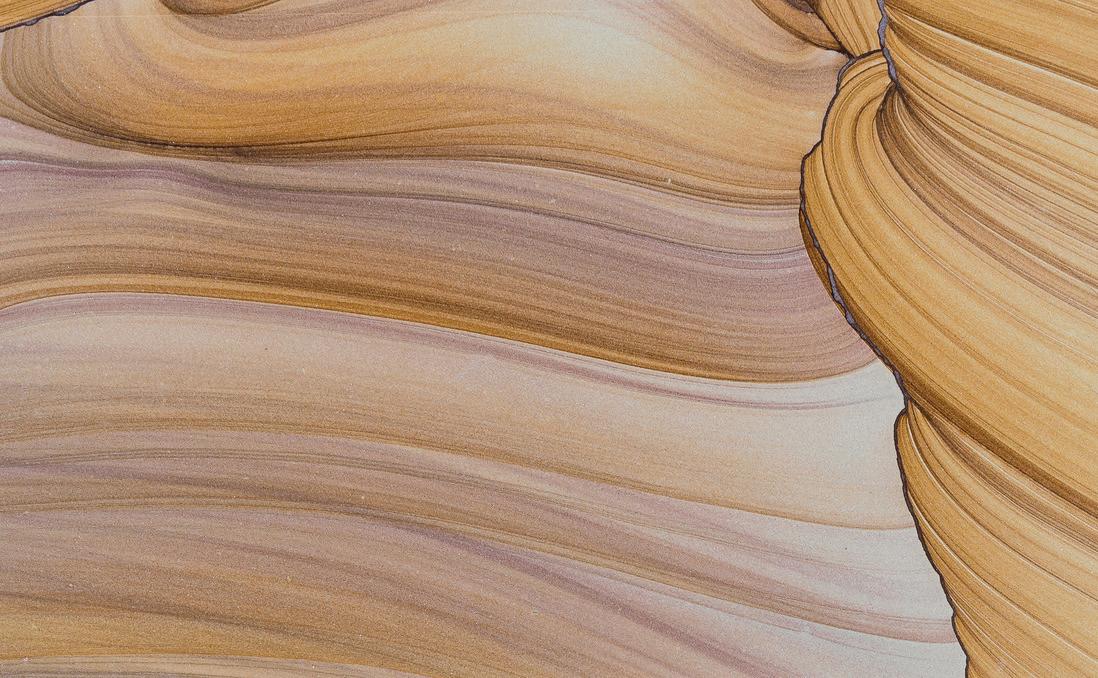

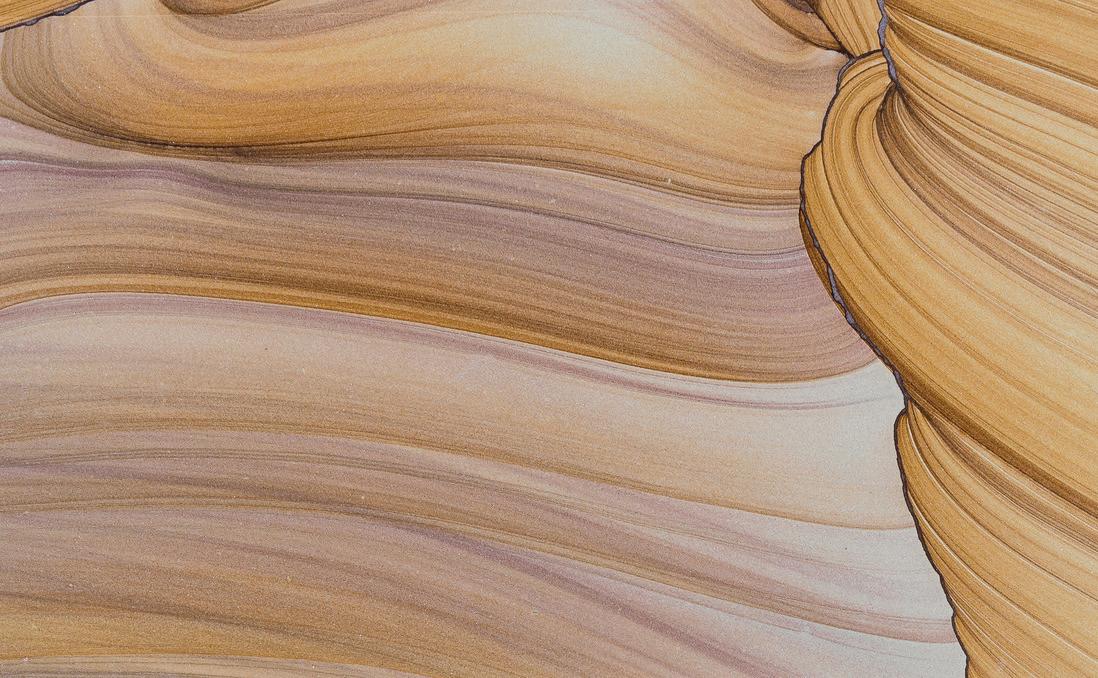

We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the lands on which we live, work and meet across the state and pay our respects to the Elders past, present and emerging. 60 Barangaroo Pier Pavilion Words: Jessica Spresser and Peter Besley 62 On sandstone Words: Guy Wilkinson 64

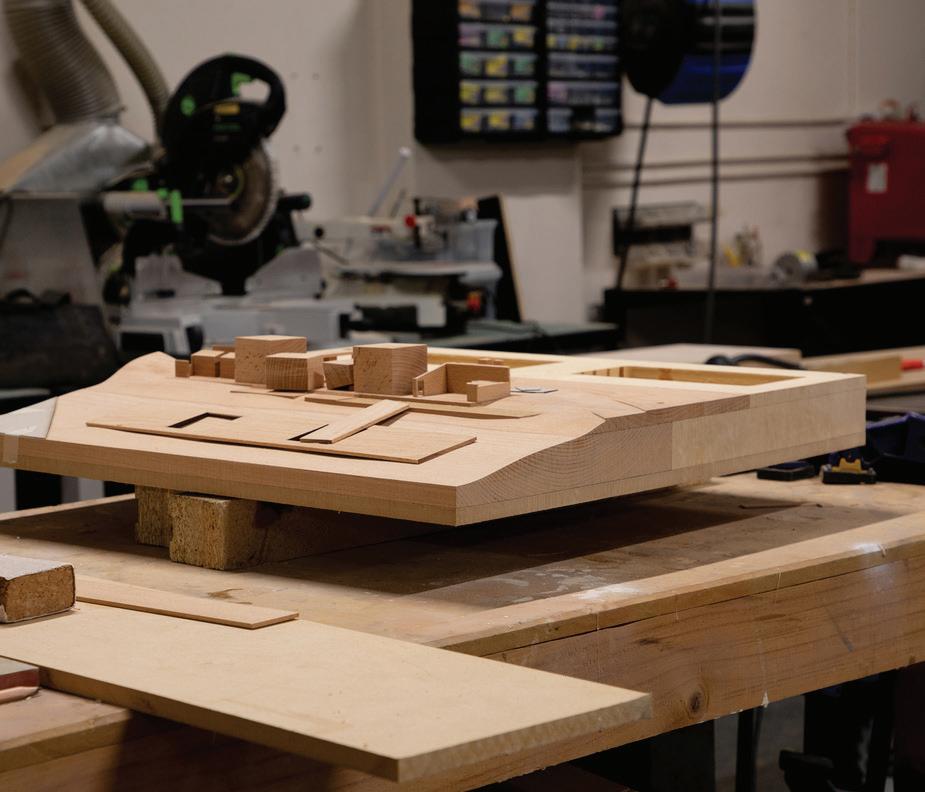

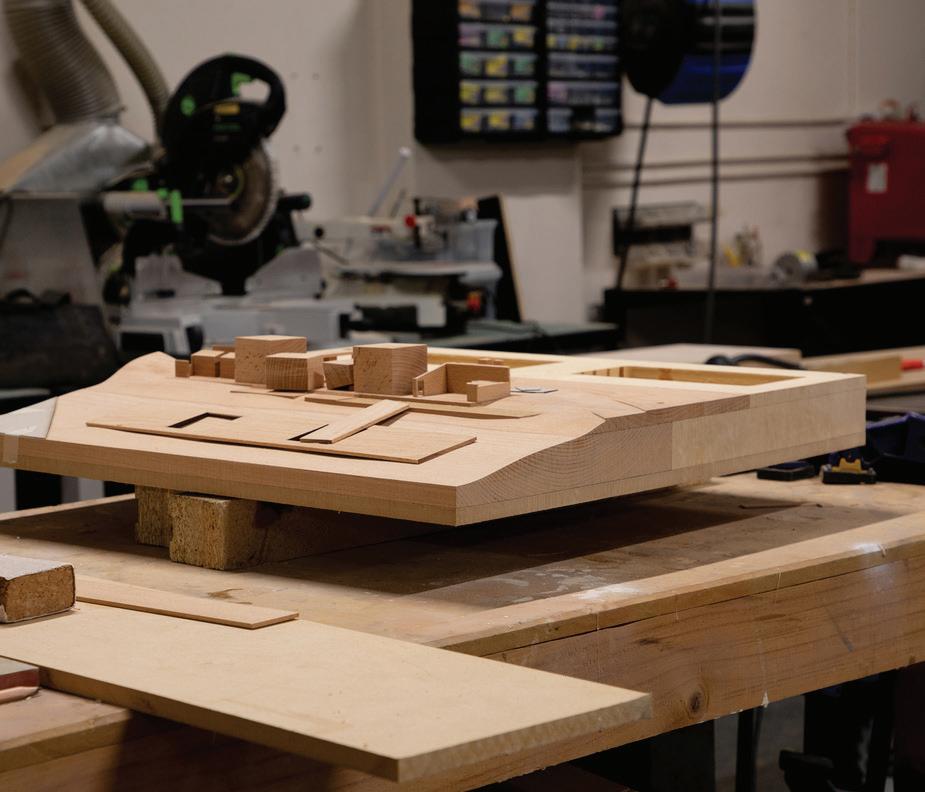

Process is product: Make models Words: Clare Dieckmann and Celeste Raanoja 38

Changes to the way we practise heritage Words: Jennifer Preston 40

Profit or profiteering? Words: Warwick Mihaly 42

Architecture’s true impact Words: Mitchell Page 44

The ethics of everything Interview: Claire McCaughan with Tahlia Hays 48

Dangerously under-represented: the absence of sustainability in fitout Words: Lucy Sutton 51

Off-cut kitchen Words: Shahar Cohen and Amy Seo 53

Specification as a funding mechanism Words: Ben Berwick 54

Material possibilities – exploring bamboo Words: Jed Long 56

The materiality of Jonathan Jones Words: Samantha Rich 58

Hempcrete House Words: Tom Gray

Seven art elements of the North West Metro Words: Peter McGregor with Michaelie Crawford 66 Touching history: The Nicholson Galleries Words: Simon Rochowski 68

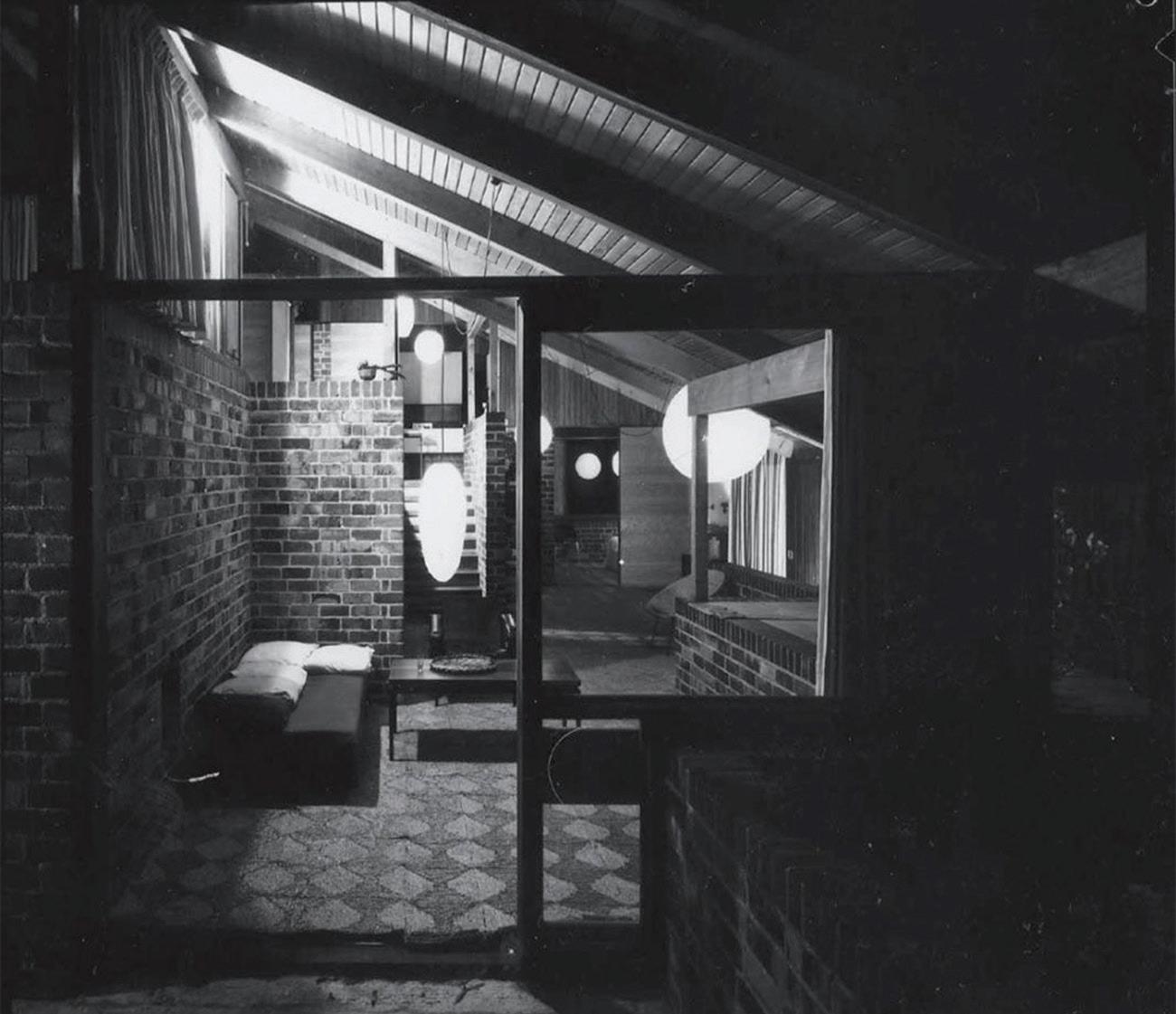

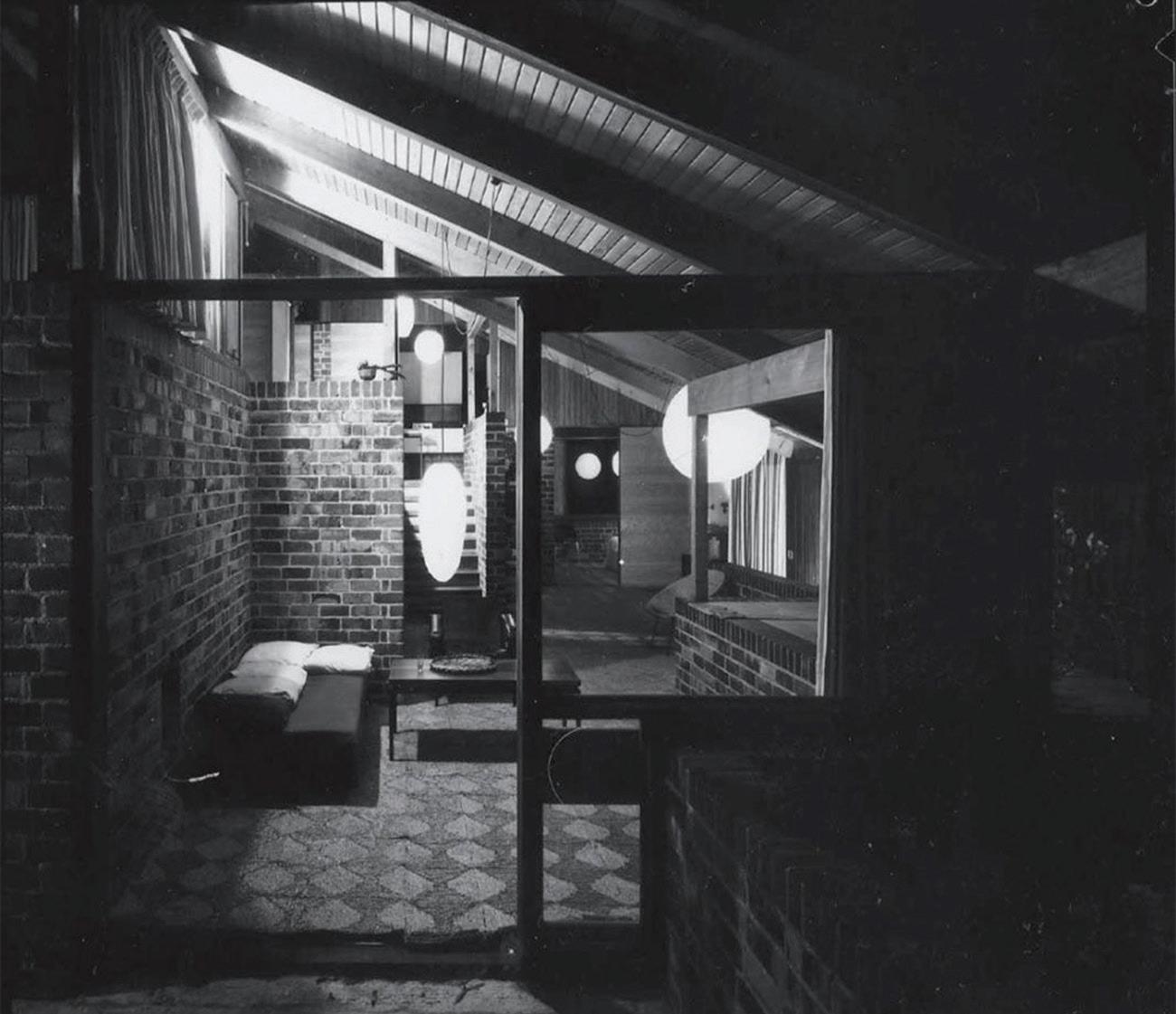

Exhibition: Revisiting Shoei Yoh Words: Eva Rodriguez Riestra 2022 NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE A WAR d S –NSW W INNERS 70 Awards and commendations 2022 NSW COUNTR y d IVISION WINNERS 85 Awards and commendations 2023 N EWCASTLE A W AR d S WINNERS 92 Awards and commendations

BOO k REVIEW 99

A Life In Planning: Bob Meyer & The Sydney Region Words: Christina DeMarco, Christine Gunn, Jennifer Norman, Brian Riera and Glen Searle

OBITU AR y 101 Vale Martyn Chapman Words: David Springett, Alan Rudge

3

It is fitting that as my NSW Chapter presidency comes to a close, the theme of this issue: Practice, mirrors the focus of my term, working with government and Industry on a number of reforms that affect our profession, as well as in education, where our next generation of professionals are learning their craft.

In its many guises, the practice of architecture is varied and the contributors to this edition of the Bulletin represent the growing diversity of what it means to be a professional within our times. And strange times they are, the articles speak of a journey of reflection, a resetting of the compass to move forward. It is certainly something I have contemplated over my term, in how we appreciate the many facets to the practice of architecture, and the value these voices are able to bring into a discussion at the highest levels of government if allowed a seat at the table and the broad scope for influence we could have, if we use our skills to advocate at every opportunity.

The longevity of our profession in defining the built environment into the future will be in its ability to recognise the diversity of talent across the profession, to celebrate individual and group endeavour through embracing collaboration and demonstrably live by the values we uphold.

MANAGING EDITOR

Kate Concannon

EDITOR

Emma Adams

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE

Elise Honeyman (Co-chair)

Sarah Lawlor (Co-chair)

Arturo Camacho

Cate Cowlishaw

Jason Dibbs

Nathan Etherington

Ben Giles

Matilda Gollan

Tiffany Liew

Kieran McInerney

David Welsh

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Felicity McDonald

DESIGNER Andrew Miller

PUBLISHER

Australian Institute of Architects NSW Chapter 3 Manning Street Potts Point, Sydney NSW 2011 nsw@architecture.com.au

PRINTER Printgraphics

ADVERTISE WITH US Contact Joel Roberts: joel.roberts@architecture.com.au +61 2 9246 4055

ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTIONS nsw@architecture.com.au +61 2 9246 4055

Laura Cockburn NSW Chapter President

REPLY

Send feedback to bulletin@architecture.com.au. We also invite members to contribute articles and reviews. We reserve the right to edit responses and contributions.

ISSN 0729 08714 Architecture Bulletin is the official journal of the Australian Institute of Architects, NSW Chapter (ACN 000 023 012). © Copyright 2021. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher, unless for research or review. Copyright of text/images belong to their authors.

COVER IMAGE:

Sacred Mountain | Peter Stutchbury Architecture

Photo: Michael Nicholson

DISCLAIMER

The views and opinions expressed in articles and letters published in Architecture Bulletin are the personal views and opinions of the authors of these writings and do not necessarily represent the views

and opinions of the Institute and its staff. Material contained in this publication is general comment and is not intended as advice on any particular matter. No reader should act or fail to act on the basis of any material herein. Readers should consult professional advisers. The Australian Institute of Architects NSW Chapter, its staff, editors, editorial committee and authors expressly disclaim all liability to any persons in respect of acts or omissions by any such person in reliance on any of the contents of this publication.

WARRANTY

Persons and/or organisations and their servants and agents or assigns upon lodging with the publisher for publication or authorising or approving the publication of any advertising material indemnify the publisher, the editor, its servants and agents against all liability for, and costs of, any claims or proceedings whatsoever arising from such publication. Persons and/or organisations and their servants and agents and assigns warrant that the advertising material lodged, authorised or approved for publication complies with all relevant laws and regulations and that its publication will not give rise to any rights or liabilities against the publisher, the editor, or its servants and agents under common and/ or statute law and without limiting the generality of the foregoing further warrant that nothing in the material is misleading or deceptive or otherwise in breach of the Trade Practices Act 1974.

FOREWOR d / LAURA COC k BURN

4

NSW Chapter President Laura Cockburn has spoken of the diversity of contemporary practice that is represented in this edition’s contributions. Salient also is the observation that practice bleeds into materiality with multiple pulses – ideological, ethical, aesthetic – and the movement of reflections effected through the arrangement of articles here is in its own way illustrative of this inter-relationship. In turn, these practice and material contemplations find a neat denouement in the built outcomes showcased in the awards section.

The Institute’s awards program recognises design excellence in rural, regional and metropolitan contexts, and this year’s NSW winners are to be congratulated for their achievement, especially those whose projects also took out awards at the national level. Our members’ contributions to the betterment of the built environment are not only through constructed projects, however. Many also generously volunteer their time and efforts through supporting, evolving and advocating for the profession and the values for which it stands.

Three such members deserve special mention here, our outgoing NSW Chapter President Laura Cockburn and the two outgoing co-chairs of the NSW Editorial Committee, Elise Honeyman and Sarah Lawlor. The chapter presidency is a big job in the quietest of times; in times of major reform, political intensities and paradigmshifting events, it is nothing short of huge. On behalf of the membership, especially the NSW membership, I thank you, Laura, for all you have given to this most important role over the past two years.

Over the same period, co-chairs Elise and Sarah have dedicated huge energy and talent to seeing Architecture Bulletin delivered with an editorial vision that provokes topical reflection and discussion to enrich the discourse. Thank you, Elise and Sarah, for your very generous contribution.

And to all the other members who make time to give their expertise and experience for the benefit of the profession through volunteering for the Institute, thank you also. You know who you are and what you give, and rest assured the Institute does too.

Kate Concannon NSW Managing Editor

E d ITORIAL / k ATE CONCANNON

5

PRACTICE ANd mATERIALITy

Untitled (maraong manaóuwi) in the forecourt of the Hyde Park | Jonathan Jones |

Photo: Sydney Living m useums

Untitled (maraong manaóuwi) in the forecourt of the Hyde Park | Jonathan Jones |

Photo: Sydney Living m useums

Opportunities for practice

WORdS: CATE COWLISHAW

The last three years have seen architectural practice grapple with internal and external issues that we’ve not faced in several generations, if ever. However, a recent roundtable discussion with a number of practices suggests the dark days of the pandemic may have been the prelude to a period of positivity for the profession.

In June, an informal roundtable discussion was held with peers from practices of various sizes, including fjmtstudio, TKD Architects, Aileen Sage and Kieran McInerney Architect, to understand how practices are finding the return to ‘normal’. The discussion focused on three areas: people and culture, projects, and governance.

The predominant focus of the discussion was people and culture. All practices were taking both formal and informal steps to consider their path forward, perhaps because culture was the biggest casualty of the pandemic, and a shortage of required skills is the largest current pressure and an impediment to project delivery.

However, the key challenge for the architectural profession remains unchanged by the events of the past few years – it lies still in rebalancing the effort of practice away from compliance and administration and towards the value architecture delivers to both clients and the wider social and economic environment.

PEOPLE ANd CULTURE

Architecture has not been immune to the issues of attraction and retention of staff created by lockdowns and a pause on immigration. A shortage of skilled staff and salary pressures have been felt universally across all levels of practice.

The shortage of talent has resulted in significant salary pressures, while fee structures are stubbornly stuck. This brings home the ongoing challenge of securing fees that properly represent the cost to practice, of delivering value and outcomes to our clients.

Like the broader Australian economy, there are no easy answers to this dilemma until international migration returns to pre-pandemic levels.

While thankfully projects largely carried on unchanged through lockdowns, the great workfrom-home experiment changed how and where architects work together. Practices embraced hybrid work to greater or lesser degrees, leading now to an examination of how best to collaborate to enhance project outcomes and build culture. An entirely remote working model is not seen by any scale or type of practice as supporting good collaboration or culture, with all the practices we spoke to consciously promoting face-to-face engagement to rebuild those habits.

PRACTICE AN d m ATERIALIT y 8

The erosion of culture through lockdowns has seen practices placing a significant focus on re-establishing priorities and re-creating the rituals that make up a workplace culture. These range from a formal review of company values at TKD Architects, practice-wide conferences at fjmtstudio and training days, through to the more social. For smaller practices, such as Aileen Sage and Kieran McInerney Architect, this extends to reconnecting with the cohort of like-minded practices they share space or collaborate with regularly.

One positive legacy of virtual work has been the ability for a wider team to join meetings and be exposed to conversations they would previously have missed. The more inclusive culture resulting from this has also broken down barriers for working across states and internationally for larger practices.

An aspect of culture with increasing importance is the acknowledgement of mental health. While much of the mental health focus during the pandemic centred around managing isolation and fear of the unknown, it is hoped that this will evolve into a general understanding and support for good mental health.

PROJECTS

It was generally observed that the day-to-day of running projects has continued relatively unscathed. This includes the ongoing focus on Environmental, Social and Governance measures, including environmental performance, Indigenous participation and gender equity, which these practices embrace, as a more holistic recognition of the stakeholders invested in our built environments.

ARCHITECTURE BULLETIN

9

HDR Sydney. Photo: Nicole England.

PRACTICE AN d m ATERIALIT y

10

Above and left: HdR Sydney Studio. Photos: Nicole England.

However, there is frustration about the ground that architecture has given up, which seems to continually increase and erode our contribution and perceived value to projects.

Project managers, facade specialists, BCA and DDA consultants etc, continue to chip away at our traditional areas of expertise. The fear is that younger architects miss the opportunity to develop valuable skills at a time when the Design and Build Practitioners Act is pivoting the industry back towards full documentation and site roles.

One increasingly prevalent role that was viewed positively by all participants is the architect as design manager, as well as architects who take on client roles as development and facility managers. When it works well, clientside architects often act as advocates and gatekeepers for design, inevitably leading to both better working relationships and outcomes. This was the case for larger practices such as fjmtstudio and at a smaller scale by Aileen Sage.

GOVERNANCE

The broader governance structures in which practices operate are also seen as having evolved positively, despite the additional administrative burden they can create. The work of the Government Architect, the State Design Review Panel (SDRP) process, and the current composition of the Land and Environment Court are all seen as promoting good design outcomes. Practices support the SDRP process but feel outcomes would be improved by a more rigorous briefing of the panel, and a shift towards a workshop approach, rather than a more traditional crit.

The downside of governance structures, and other approval and reporting requirements – including such wide-ranging tasks as development consents, Workplace Gender

Equality Agency reporting, annual CPD and registration requirements, Design and Build Practitioners Act registration, increasingly onerous tendering requirements – is the significant amount of paperwork architects and practices are managing. This burden is particularly felt by small practices that may not have the support structures of larger practices.

This is as good an illustration as any of the price we pay for not communicating our value effectively. Surely an architect’s time is better spent on the skills for which we are trained. This is a focus that can only be achieved through fee structures that deliver suitable support services and allow us to add value where it matters.

Overall, the profession is positive and moving practices forward, with a particular focus on using this pivot point to rebuild culture and strategic goals. We are optimistic about many of the recent changes such as the Design and Build Practitioners Act, while still under pressure to find the skilled teams we need to deliver effectively. The key pressure on professional practice remains unchanged by the pandemic years – effectively communicating our value. ■

Cate Cowlishaw leads HDR’s Architecture Business Group across Australia with over two decades of experience serving in leadership roles with global, national and boutique architectural practices. Having spent much of her career as a key member of practice management teams, she has deep industry experience across all aspects of professional practice. Cate was previously studio director and head of business development at Bates Smart before joining HDR as the managing principal. Cate is currently the Chair of the NSW Chapter’s Gender Equity Transformation as well as a member of the Editorial Committee

ARCHITECTURE BULLETIN

11

Practising in strange times

WORdS: dAVId WELSH

In late 2021, as we rushed wearily towards the Christmas break, our practice managed to get a few tender packages out the door, all ready for prospective builders to start pricing on their return from the Christmas New Year break in early 2022. The projects I’m referring to were smaller residential projects that we had taken a great deal of time and care to work through with our clients, who in turn were keen to make new starts with a new home and put the COVID times behind them.

The previous few years had been a tough time for many people in the construction industry. While builders had generally continued on through COVID-19 restrictions, many had trouble getting subcontractors to site, issues with sick staff and then, as the pandemic seemed to be easing, the added complication of keeping staff as people re-assessed their priorities for their post-lockdown lives. Often construction times had blown out and stress levels were still high, so we knew that an added degree of flexibility in the construction process was called for –something it could be argued was long overdue.

With this in mind, we were wary not to overload prospective tenderers with tight deadlines and unrealistic expectations. Not wanting to waste anyone’s time, before we formally called for tender prices we discussed our expected construction cost range with the tenderers, just to make sure they were interested. The tenderers we approached all thought the range was reasonable, and so off we all went on our respective breaks.

As the 2022 work year cranked up again, we looked forward to getting our tender prices back in – and then we saw the prices. The grumbling rumours we had heard of impending inflationary pressures were suddenly very real, with the prices coming in between 100- 250% higher than the pre-tender estimates.

As our clients (and ourselves) went through four of the five stages of grief – denial, anger, bargaining and depression. The fifth and final stage – acceptance – hasn’t fully resolved itself just yet (at least not in our minds), as we try to learn from the experience to establish what we might have done differently.

Anecdotally, we were finding some of our peers had similar experiences around this time. We also sought solace in the Australian Institute of Architects community online forums, where similar stories were being shared. This made us feel a bit better that we weren’t alone, but it still didn’t explain why this was going on. In looking for some explanation as to why the market was behaving like this and establishing when things might return to normal, we attempted to find some definitive data to measure our own experience; however, this proved particularly tricky.

The Cordell Construction Cost Index showed national residential construction costs increased 10% in the 12 months to June 2022, which doesn’t really explain the increases we had experienced. At the same time, analysis by the Housing Industry Association and News Corp Australia found that the typical house build cost soared more than $94,000 in 15 months. With the average construction cost of a new home in Australia sitting around $450,000, these figures suggest an increase of more than double the Cordell figures. While this didn’t really explain why we experienced such high tender costs, if the potential risk of building an architecturally designed home was taken into consideration, then perhaps it offered some insights into why the building industry was particularly nervous when we embarked on seeking our own tender prices.

Our commercial and public projects also experienced sticker shock, although not to the same degree as our single residential projects. All the same reasons were given – and all were out of our control.

PRACTICE AN d m ATERIALIT y 12

Looking forward, we are wondering if things will ever return to normal. Prices would have to drop significantly from their current position. The sort of deflation required for this to happen would likely present ramifications much more damaging to the industry than the discomforts we are currently experiencing. Higher prices might prove to be easier to handle than a recession, and so, anecdotally again, we are hearing reports that business and construction plans will once again need to be recalibrated and adapted to deal with these higher prices, albeit with a lower future inflation rate than that we’ve experienced in the last 12 months.

Pressures on wages, where, and how we set our own fees for future projects, changes to construction contracts to allow contractors to adjust their costs as process rise, or contractors going bust because they couldn’t adjust their contracts, are all part of the altered landscape we are going to have to deal with in the shortto mid-term. How to equip ourselves with the tools to give clients good advice on costings, particularly in accordance with our obligations under the NSW Architects Code of Professional

Conduct is something that is of particular concern to our practice. These are all difficult questions, none of which we have any absolute answers to. The best thing we can do is be clear in our communications, lean in on our professional peers and our shared experience, and keep practising to the best of our ability. ■

ARCHITECTURE BULLETIN

David Welsh is a director of Welsh + Major.

13

Above and right: The practice team at Welsh + major. Photos: miki Sakai

Changed approaches to working

WORdS: CHRIS BOSSE

As we all know the pandemic has brought about many changes in society, from working from home to de-urbanisation, from isolation and disconnectedness to loss of income, global shortages of materials, and challenges in finding staff. Some of these changes were already in train but the pandemic has fast-tracked them.

The impacts on LAVA have been profound as we faced the increased demands of global flux. LAVA has always worked as an international network using digital communication and design tools, so this helped us to deal with these new scenarios. Our business model was adapted by strengthening our methodologies – the way we work, the type of projects and staffing.

HOW dId LAVA COPE WITH THESE CHANGES?

Being a multinational company (with offices in Australia, Germany and Vietnam) with diverse studios meant that while one office saw some delays to projects proceeding, others had ongoing or time-specific projects. The German offices had huge projects such as the German Pavilion at Expo 2020 Dubai which, although it opened a year late, provided regular work with a major government client. Having different locations across the globe meant we could recruit additional people or reallocate staff to meet the changing work demands.

We had been dealing with long distances and remote communication since our inception in 2007 when we started a project in Abu Dhabi working jointly from our offices in Germany and Australia. I remember having my laptop, booting it up for a few minutes before coffee in the morning, followed by a phone call with German directors Tobias Wallisser or Alexander Rieck in our Stuttgart office.

Since the introduction of smart devices, in particular the iPhone, this has changed completely. Like other practices, we work with any imaginable number of apps and devices from Slack to Miro boards to our in-house tool the Poolarserver. We all have meetings on Zoom, Teams, WhatsApp, Skype, Messenger, Zalo, to name a few.

We track our hours and our design progress online in Google slides, we distribute weekly reports that can be accessed and reviewed worldwide.

Gone are the days of last-minute changes at the printshop, scratching ink from a drawing and filling it in with a pencil. We are now able to change a presentation remotely in real-time, even while it is being presented to the client. So the deadline is no longer the printing date or the saving time of the InDesign file. It’s literally when the eyes of the clients gaze on that particular page on the screen.

We have also implemented VR and AR into our presentations, where the client accesses a 360-degree model of their project and gets transported into their new space virtually. This actually made us realise how little clients sometimes understood their project before seeing it in 360.

On the construction site, we put an Oculus Go onto our builder’s forehead, and they got the surprise of their life at what was going to be built, despite having seen and reviewed and quoted on all the drawings and ordered the materials.

PRACTICE AN d m ATERIALIT y

Who led the digital transformation of your company?

A) CEO B) CTO C) COVID-19

14

My favourite joke of this period:

We have found that quite often virtual meetings can be much more effective, people are much more available and things can be discussed much more easily. Gone are the days of flying 24 hours for a meeting only to find that the client has cancelled at the last minute.

All these communication strategies have helped us to adapt to meet the new normal.

A flexible approach to working helped us to transition to working from home. Australia’s border closures saw the loss of some staff and meant that I personally wasn’t able to travel and meet with staff in other office locations, which was difficult. Lockdowns in other nations such as Vietnam also made it challenging.

But of course like many organisations are also finding, it is great being back together in the office now, and having a chat before diving into business with clients and staff, and visiting the actual site of a future project rather than a desktop study.

On a personal level I had just bought a dilapidated house in Sydney so was able to focus on that project.

And since the opening of international borders, we’ve been pulling out all the stops and everybody is starting off twice as fast again. ■

ARCHITECTURE BULLETIN

Chris Bosse is a director at LAVA.

15

Exterior view. Image: Taufik kenan

Better together: starting a practice and a family at the same time

WORdS: STEANI CILLIERS ANd CHRIS mULLANEy

Starting a business and a family at the same time might sound like a nightmare, and we are not here to tell you that it’s been easy, but lately, we’ve realised the juggle brings with it substantial long-term benefits for our practice.

When we first met, we were deeply entrenched in the 24-hour studio culture at the University of Newcastle. Our first thoughts of starting a practice together reflected this studio model of late nights, working weekends, and going the extra (unpaid) mile for the love of design. The romance of this vision had already started to

fade after a decade of working in the industry and while we had built much better work-life boundaries, the balance wasn’t there yet. In a strange way, having a child became the antidote to this as we have come to learn that nothing enforces knock-off time like having a child to care for.

Our practice culture and our parenting dynamic have been forged simultaneously in the context of this uncompromising commitment, and privilege, of raising a child. So, it is rewarding to reflect on what we have learned so far and what it might mean for our studio moving forward, or any studio in a similar position.

It is well understood that it takes a village to raise a child but there are interesting parallels to this proverb and establishing a small design practice. A large motivation for starting our own studio was our plan to relocate from Sydney to Newcastle. We liked the idea of being closer to family and basing ourselves in a regional city during a time of great transformation. To make this transition easier, we moved in with family for six months while we searched for somewhere to live and build a financial runway for our business.

Similarly, our professional network was instrumental in getting our business off the ground. Most of our early project leads came from architects, consultants and builders that have taken an interest in helping us raise our new venture. The generosity of our peers has also filtered through at an operational level, so while we have started our own studio, we don’t practice in isolation. Together we exchange

PRACTICE AN d m ATERIALIT y 16

Steani Cilliers and Chris Mullaney, co-founders of Muci. Photo: Jacquie Manning

knowledge regarding the pragmatics of setting up a business, assisting each other with design reviews at critical junctures in projects, and sourcing new consultants and contractors in locations we haven’t worked in before. Having worked in medium-sized practices in the past, we are glad to have found ways to preserve some of the studio culture that we enjoyed in those formative years. It is our aim to build upon these relationships by finding ways to formalise these knowledge-exchange experiences into regular sessions.

Additionally, we have had to tackle issues of workplace flexibility head-on, discovering that the level of flexibility required exceeded our expectations and our ideal scenario has continued to change over the three years since our daughter was born. We wonder if this level of variability is being fully catered for as offices roll out flexible arrangements in a one-size-fitsall approach, such as standardising which days everyone will work from home.

Pandemic-enforced work from home was fantastic with a three-month-old and was a big impetus for following through with our plan to start our own practice. However, this approach eventually burnt itself out as we entered toddler territory and home life became louder, messier, and more distracting. Our office is now in a charming old bank building a short bike ride from home and we enjoy the new sense of routine and conversations with other adults, if only while grabbing a coffee. Also, as any parent will tell you, by far the biggest curveball has been childcare – or lack thereof.

This year alone we have missed 23 out of 75 days of planned childcare due to sickness or carer holidays. Being closer to family has been crucial to overcome this, and while it’s not great for monthly targets, working for ourselves has removed a layer of difficulty because we don’t need to continually notify employers about our shifting schedule.

The point is, the best working arrangement will be different for everybody and will undergo continual refinement. For our part, we have found this challenge to be a circuit breaker for bad habits around work-life boundaries. We have also come to recognise that we are most productive for a solid core of four to six hours during the day and that evenings are better allocated to family time or personal endeavours. We think this is likely true for most people, for us it just took starting a family to finally make these structural changes. So, while it has been a juggle, we think that our business and worklife balance will ultimately be better for it, being negotiated together, from the outset. ■ Steani Cilliers and Chris Mullaney are co-founders of Muci, a design-driven studio working on Awabakal Land/Newcastle.

ARCHITECTURE BULLETIN

17

Growth through uncertainty –People-centred practice

WORdS: STEVEN dONAGHEy

With experience in large practice for most of my 25 years in architecture, establishing a new team in Sydney for a growing national practice was a great opportunity. Like many before me, I started at the base of the mountain, looking forward to a year of fresh and renewed introductions and working towards our vision of the future.

In March 2020, however, the COVID-19 pandemic sent us all into social and professional retreat. After our initial fears for the health and safety of family and friends were addressed, if not resolved, we began the task of working through the implications for our industry.

Working predominantly on public projects, developing the studio and sourcing new projects in such uncertain times was concerning. With operational costs initially contained due to remote working, new staff to grow the studio combined with technology solutions to collaborate successfully were critical factors.

This early growth presented unanticipated challenges such as recruiting new staff followed by inductions over the dining room table on a Sunday afternoon to maintain work-from-home arrangements. As our studio was established remotely we rapidly expanded our use of mobile technology, meaning the periods of isolation and then our return to the studio did not impact operations as heavily as others.

Early challenges gave way to novelty: Friday drinks online received a mixed reception, team meetings in the park maintaining social distancing protocols were welcomed such that we plan to continue them, and business development coffee meetings online were not quite the same as meeting people in person. Online meetings required new protocols, though the opportunity to visit colleagues’ and clients’ living rooms offered unseen depth to their personalities. The favour was returned when a screen of smiling consultants signalled the arrival of one of my children to the meeting.

Global health concerns combined with ongoing home isolation had the effect of heightening the senses. I remember the anxiety of presenting a new design concept for a major project to

PRACTICE AN d m ATERIALIT y

18

“At the time, December 2019 seemed like an opportune moment to launch a new studio in Sydney.”

a client without the usual studio pinup and collective affirmation, followed by the solitary moment of jubilation when we realised they were as excited with the proposal as we were!

Throughout the studio’s remote working experience staying connected with team members was paramount, and simply being there for each other made a significant difference to our day. New personal opportunities, such as dropping the kids to their actual school after many months of home schooling, or easy access to health and fitness regimes, blurred conventional working hours and required everyone in the studio to adapt to these new routines.

Our workplace has shifted from our living rooms to a shared workspace, and earlier this year our own studio, with continued discussions around a shared vision for the practice. Operationally this evolution continues as we redevelop assets such as social media and website platforms together with new digital practice management tools.

Over the past few years further constraints were presented to our team in addition to an ever expanding set of modern professional practice considerations. Client-friendly tender prices seen early in the pandemic when future work for contractors was uncertain, swiftly shifted to supply and labour shortages which are lifting construction costs daily, challenging the way we design and deliver projects. Building site closures due to the pandemic and extended wet-weather periods added further pressure to site-based teams.

These challenges have reinforced our approach as a practice to listen to clients and stakeholders first, then share our expertise to tailor solutions for each project. We continue to challenge for better outcomes but with a heightened sense of empathy for everyone involved in the process. This has been one of the better outcomes of the global pandemic.

From the outset of the pandemic, we focused on fostering positive relationships with trusting and supportive teams, engaging with those

around us more than simply pursuing awards as a coveted project dividend, and assembling teams and business connections as a rich seam of growth, for now, and into the future.

Today, many people remain uncomfortable returning to workplaces or face-to-face meetings. And while we believe that the hybrid work/ remote model of practice will remain in various forms, our experience suggests that despite technology supporting remote work, this approach does little to develop a sense of team culture.

As we emerge from the worst of the pandemic, businesses face a combination of slowly reopening borders and domestic migration while as a studio we seek to embrace new project opportunities. It is important that we move past the pandemic mindset of looking after ourselves and expand our consideration of others if we are to realise the opportunity to grow stronger together.

Following a tumultuous yet exciting period, we are determined to resist simply returning to a pre-pandemic world of past workplace discontent, letting the opportunity to create a future-focused way to live and work while developing meaningful relationships pass us by. Instead, we seek to lead our practice, industry and communities towards a more supportive, empathetic and productive future. ■

Steven Donaghey FRAIA is the NSW principal and nominated architect of CO.OP Studio located on Gadigal Country in Surry Hills. He completed his B.Arch with First Class Honours at UTS, is a former NSW Chapter Councillor and is a member of the Australian Institute of Architects NSW Practice of Architecture Committee.

ARCHITECTURE BULLETIN

19

The value of people in practice

WORdS: Amy dOWSE

Ethics have always been important to me, embedded throughout my upbringing. I have always strived for an empathetic approach to the collective creative process and value people and their diverse contributions.

My first two experiences as a student of architecture were in practices where ethical employment was evident from day one. There was a genuine interest in mentoring and valuing people’s time and commitment.

Throughout my career as an architect, I have worked for practices of varying scales, from sole practitioners to large global corporations. I have experienced different approaches to ethical employment and workplace culture. What I have learned from this experience is the value of respecting my time and those around me, whether they are colleagues, clients or collaborators.

From my experience working and collaborating with a wide range of practices, I’ve witnessed an expectation at some practices to work additional hours as required, for a fixed salary which I believe is detrimental to an individual’s wellbeing. This experience was reinforced by reading the results of the 2021 practitioners survey which showed that more than one-third of respondents worked regular unpaid overtime causing job dissatisfaction. In my experience,

such culture leads to a high turnover of staff, with the flow-on effect of lost knowledge and skills within a practice. It’s widely accepted that the cost of hiring and retraining far outweighs the cost of nurturing staff in their career. But more than this financial consideration, ethical workplace culture leads to the attraction and retention of talented individuals and is an investment in the practice as a whole.

The culture within my current practice was not fully evident to me in my younger years. However, in hindsight and with the benefit of working at other practices in Australia and internationally, I now recognise the innate culture and business model. While I believe it is unique, I don’t believe it is by any means revolutionary; the principles are simply good practice and a recognition of the value and trust we should have in our team members.

Last year I became a practice director, making the shift from being an employee to an employer; a change which has given me a newfound appreciation for the complexity of issues faced. I’ve become an active participant in the balancing act of running a viable and sustainable business while advocating for the individual. Looking at practice management from this lens has cemented my belief that creating an environment to attract and retain the best talent is the most sustainable way to practice.

Fundamental to a practice’s ability to provide an ethical workplace is establishing client-architect agreements and workplace conditions that enable an environment conducive to people doing their best work. To me, this means setting realistic fees, scope and programs from the start by educating clients on the value good architecture can bring to a project. Setting up realistic project expectations allows a practice to provide competitive remuneration, paid overtime and the ability to support carers through parental leave payments and other related initiatives. In addition, by structuring resourcing to allow all roles to be flexible to suit individual needs, time for peer-to-peer mentoring, training and study assistance, these aspects can be built into budgets and employee time allocation to foster career progression.

PRACTICE AN d m ATERIALIT y

20

I consider the idea that if you value your people, you need to value their time central to ethical employment. This means having a business model that allows you to set the work conditions you desire while balancing the fees and scope of projects that suit this model. Resourcing projectbased work is inherently difficult, no matter which industry, with leaders forced to respond to factors outside of their control, sometimes daily.

Having an agile workforce is vital to us in an era of economic instability and is an effective way to manage our resources to suit project load. One example of how we generate this agility is to, at times, ask people to increase or decrease their hours to suit the current project demands. This has enabled us to service projects effectively without hiring and firing. The process is transparent and completely voluntary. People are consulted, guaranteed their salary and if they choose to increase hours they are renumerated for those additional hours. If they choose to work less, their salary is prorated and feedback has shown they enjoy other aspects of their life during this quieter period. We’ve found this transparent culture and approach to resource management has equated to longer-term employees and increased wellbeing, enabling skills and knowledge to remain embedded within the practice.

A sustainable business model also means creating a positive design culture, by instilling work methods that are collaborative and lead to better design outcomes. Creativity and good design come from allowing staff the space, time and agency to develop design skills, both on their immediate projects and by taking a wider view of their personal development.

Long and unrewarded hours do not create the best environment for people to be their most creative and effective. While we all feel the pressure of requests to reduce fees and have seen substantial undercutting occurring within the industry, I believe this is unsustainable and generally disrespectful to ourselves, our staff and the public. It is detrimental to the wider industry and I believe we should all hold ourselves to a higher standard. It is our collective responsibility as leaders in the profession to

advocate for more respectful practices. We need to focus on the value in what we provide our clients - a unique service and a design process that inherently takes time.

In an era of significant wages pressure, resource shortages, and unprecedented economic, climatic and global turmoil, there are no doubt challenging times ahead. Ethical practices are, however, sustainable and necessary to ensure the wellbeing of our people and our industry. The broader community benefits by retaining and attracting more talented people into the industry, enhancing their ability to design and help create the future places where we live and work. ■ _____

Amy Dowse is an architect and director of Tzannes. She has a wide range of project experience at leading practices in Australia and internationally. She is a strategic thinker who is committed to the professional development and growth of staff as well as advancement of the studio and the wider industry.

ARCHITECTURE BULLETIN

21

The cost of caring

WORdS: ByRON kINNAIRd ANd LIz BATTISTON

The first major survey of the Wellbeing of Architects project – a three-year study funded by the Australian Research Council Linkage Projects scheme – has shown that people working in architecture are likely to have low personal wellbeing scores, elevated levels of psychological distress, and higher-than-average levels of burnout. If there is something wrong with the way architectural practice works, how does this reconcile with the commitment and fulfilment that so many architectural workers feel?

When our survey asked people working in architecture what factors were negatively affecting their wellbeing, the results were clear: timelines, deadlines, and inadequate resourcing of projects with inadequate fees. Many of our respondents articulated the impact of underquoting time and resources for their work, sacrificing their own time to meet their professional obligations and responsibilities.

As one respondent said, “We consistently accept more responsibility and workload than we get paid for by clients, and put pressure on project teams to ‘make it happen’ even if the goals aren’t realistic with resourcing.”

Many respondents spoke of this complex relationship between industry norms, external pressures, and a perception that individual employees often bore the brunt of cutting costs and corners.

“Clients and builders expect everything from us and don’t want to pay for what we’re worth. Therefore, the directors of the architectural firm are putting pressure down the food chain to work for free.”

We found it revealing that on the whole respondents were committed to their profession and took pride in their work but said they would not necessarily recommend a career in architecture to others. While we continue to analyze this response, it was perhaps not surprising that respondents found it difficult to reconcile these challenges with their personal values and commitment to the work.

Respondents felt frustrated at not being able to break the cycle and reticent about their own participation and contribution to wellbeing challenges at work but also at a wider industry scale. As one put it:

“We have devalued ourselves as a profession. We compete with each other for jobs by reducing fees instead of standing together. We’ve let go of our power in the industry. It seems most firms keep going this way to save face and let the workers’ wellbeing suffer.”

This self-awareness and help-seeking attitude is incredibly important to nurture change. Promisingly, there was a resounding call to break this cycle at a structural level – calling on collective action to bring about change:

“If the architecture industry could band together to stand up, at a governmental/strike level, to the other players in the industry who exploit them, then there is a hope of substantial change. Without everyone involved, other companies will cannibalise each other to the benefit of nonarchitects. Fix this, fix the hours worked back to 40hrs/week, and all of a sudden the pay rates won’t seem so bad.”

PRACTICE AN d m ATERIALIT y

22

In understanding the problem better, we see what is working too. We found that the strongest career satisfaction for people working in architecture correlated with a greater sense of optimism about their career, a stronger sense of connectedness to others, and greater autonomy at work.

The respondents who reported workplaces that actively supported employees’ wellbeing and shared common values were vocal about their loyalty and commitment to their role. These respondents often spoke to their workplaces as proof of the concept that change was possible and underlined the impact of external industry challenges.

“I work in a practice that values the wellbeing of its staff and tries to assist with flexible working arrangements, additional days of ‘office leave’ beyond annual leave, but it is hard to change the economics of a profession that does not pride its self on charging substantial fees to value what it takes to produce good works. Design is becoming more and more valuable in the community, but the reflection in architectural salaries is poor.”

There is much work to be done to improve the wellbeing of people working in architecture. Our conversations with the community provide the strongest sense that the will, commitment and care are there and this fuels the Wellbeing of Architects project to work alongside and with practices to translate this into resources, tools, and – we hope – actionable change.

Visit www.thewellbeingofarchitects.org.au to read our detailed report The Wellbeing of Architects 2021 Practitioner Survey, Primary Report, other publications, and project updates. ■

Byron Kinnaird is a researcher and educator with a deep interest in the cultures and structures of the architecture profession. Byron is a Research Fellow at Monash University under the Wellbeing of Architects project.

Liz Battiston is a research officer at Monash University Art, Design and Architecture assisting The Wellbeing of Architects project. Her practice is located at the intersection of sociology and architecture.

ARCHITECTURE BULLETIN

“

23

Clients and builders expect everything from us and don’t want to pay for what we’re worth. Therefore, the directors of the architectural firm are putting pressure down the food chain to work for free. “

Scrolling past complacency: a new generation of discourse

WORdS: ELSA yA SHI BAkER

“I don’t believe in cancel culture” was the response I received when I recently brought up the subject of popular meme accounts to somebody more established in the discipline. I was initially puzzled by their deflection, but this was the moment for me that affirmed all the doubts I had on the topic of complacency. When I started my formal architecture education at university, I was naive; I had no reason to believe that what I was being taught could ever be problematic. Before I even realised it, the first value that would be instilled into me was how much valour there is in suffering. As I began my second year, I felt genuinely lucky to have survived the first-year mass quelling of the ‘weak’. We began to sleep less and work more as we were constantly reminded by those who taught us that this was just a taste of the long hours we would have to endure in the real world. I suffered in silence as my mental and physical health declined, and I accepted that these were the terms of having the privilege of being in the spaces I desperately wanted to be a part of. I wasn’t coping, and it was a ‘me’ problem that I would have to overcome one day. Complacency was easy because we had no time or energy to ask questions.

I discovered the Instagram account @dank.lloyd. wright (DLW) at the midpoint of my second year. I was exhausted and the disillusionment was starting to creep in. I was an avid follower of DLW’s posts, and what began as a light-hearted, “haha that is so relatable”, quickly became much more as I became exposed to what was happening elsewhere. One after another: the OMA internship listing, SHoP employees attempting to unionise, the Sci-Arc roundtable, and most recently, students coming forward from UCL Bartlett and the subsequent open letter. It was immediately clear that there are fundamental issues in the discipline beyond what was a ‘me’ problem. I felt like I was arriving at a better understanding of what was happening in our discipline, yet this was not the inward reflection that our theory classes were concerned with. Whenever DLW was raised, cancel culture was on more than one occasion the automatic response, or it would simply be laughed off and I couldn’t understand why. It was the first time these parts of my architectural education had been affirmed by others on a global scale, yet around me, there was still a stigma around where this information was coming from. It seemed like there was a generational dichotomy between what could be

PRACTICE AN d m ATERIALIT y

24

viewed as actual discourse, and it made sense, given that the traditional ascent to legitimisation required many years of formal education followed by a book, thesis or lecture at an institution. A meme page was crude and it didn’t follow the right way of doing things – it was not something to be taken seriously.

I am nearing the end of my undergraduate studies and probably still incredibly naive, but also optimistic. I know there is much still for me to learn and understand about the ‘right’ way of doing things, but this is what I know for sure. I know that generational cycles of toxicity will not be broken by one viral post, but as a Gen Z-er, it is not the books or the lectures that we are sharing with each other as a jumping point for conversation. It is the memes. The best forms of discourse and education are the ones that are the most accessible to us, and the self-seriousness of this discipline is the most significant barrier. There is merit in being able to speak to each other like normal human beings, and you are no less of an intellectual for it.

Formal academia spaces have had a long history of gatekeeping access, but the meme space has been inclusive from the get-go as a place for these conversations about reform.

As loud as the persona of the DLW account comes across as this kind of bottom-up progress is discreet. Exploitation in practice will not cease to exist overnight, but as our generation slowly enters the workforce, there will be more of us who will firmly say no to unpaid overtime, for example, all because of a meme we saw in 2021 that was a direct callout of OMA’s “no 9 to 5 mentality.”

Ultimately, the question is not about whether or not you believe in cancel culture. This is about whether you choose to be complacent about the very problems that memes bring to light and whether you want to perpetuate this tired cycle onto the next generation. If you still fear meme accounts or cancel culture, think about why that is and what is at stake if you are held accountable for your actions. ■

Elsa Ya Shi Baker recently completed her undergraduate studies and works at a multidisciplinary studio.

ARCHITECTURE BULLETIN

25

The unnaturally shrinking profession

WORdS: kERWIN dATU

During my student years, it was common to hear architects lament our profession’s shrinking stature. Design-and-construct was in its ascendency; the architect as superintendent was in decline. Leadership of the design team was shifting to the project manager, a hollow man who was all power and no accountability. Architects needed to take it back from them, we fumed, even if some of them were erstwhile architects. Not that we ever tried. We were happy to be allowed to focus on design.

The fundamental schism was never between project management and design; it was between design and construction. At a certain age in history, architects and master builders were one. Etymologically they are the same. Over the centuries we architects lost interest in doing any of the work of the builder. Indeed, we partly define our place in the construction industry in opposition to the physical act of building.

Each year a few more architects leave architectural firms to become design managers in large contractors. The design-manager role is a direct consequence of the designand-construct model. It entails the planning and coordination of large volumes of design documentation. It is a natural enlargement of the design coordination function of an architect. The hiring of experienced architects for this role is an acknowledgement by large contractors that they need the competencies of an architect overseeing the design component of their design-and-construct services. A handing back of the design team leadership to an architect, just not to one sitting inside an architectural practice.

Yet we architects do not see it this way. Instead, we joke about our colleagues’ departure from the profession and wonder if they will ever come back to being an architect. We imagine that the natural ambition of an architect is to become senior enough to delegate away the coordination function so as to focus on design, not to perform coordination at higher levels of management within the industry. Becoming a design manager is not seen as any kind of promotion or progression; it’s a move sideways or even backwards in an architect’s career. This is reinforced by regulatory expectations: an architect becoming a design manager is one ready to relinquish their registration; only the architect designing the architectural package needs to be registered, we think. It is not so, say, for railway engineers, for whom design manager is an integral senior role that requires the engineer to be chartered, unlike the engineers focused on designing the individual disciplinary packages, who need only be members of their institution.

The scale of a conventional project has grown since my student days when a high-rise was the largest building we were inclined to imagine being delivered under a single contract, the exclusive domain of the city’s largest practices. Now it is increasingly conventional for small boutique studios to undertake high-rises and correspondingly for governments to award entire regeneration precincts or whole corridors of infrastructure to a single contractor for 11-digit sums.

The demand for individuals to specialise in the design-manager role grows in proportion. It is natural for design managers, project managers and other managers in the construction industry to imagine their careers progressing similarly, from buildings to precincts, precincts to corridors, and corridors to whole portfolios of projects. They are all performing managerial functions that architects performed at some point in history, and to varying degrees still perform on smaller projects, as the individuals themselves may have done inside architectural practices. If they started out as engineers they will be applauded as and by engineers all the way to the top. But if they started out as architects they will likely have to say goodbye to their fellow architects long before they get there.

PRACTICE AN d m ATERIALIT y

26

The unnaturally shrinking profession. Illustration: kerwin datu A growing number of specialisations. Illustration: kerwin datu

Not only do we architects define ourselves in opposition to the activity of building, but it seems we also define ourselves in opposition to the activity of managing. Want to do anything managerial that you do as an architect but at a larger scale or more specialised way, and you must leave your architectural practice to join a contractor, engineer or other entity large enough to require you, and abandon the disciplinary title that you have studied and worked so hard for. We should be celebrating architects who step up to larger scales of undertaking, not making jibes about the dark side and seeing their names slip from our register.

The Architects Act defines architectural service only as “a service provided in connection with the design, planning or construction of buildings that is ordinarily provided by architects”. It defines individual architects only as individuals registered under the Act, which can only be achieved if one has obtained the competencies of an architect. Thus the architect’s role in the construction industry is only as broad or as narrow as the functions to which we apply our competencies. If certain management roles come to be performed predominantly by erstwhile practising architects, dependent upon the competencies of architects, then the performance of those roles becomes a service ordinarily provided by individuals who are

architects in everything but title. It becomes purely a matter of industry convention that an architect inside an architectural practice performing management functions on small projects must be registered as a practising architect, whereas an erstwhile practising architect inside a large contractor performing a management role on large projects need not be. And it is quite a perverse convention if it requires individuals on smaller projects to take on the public accountability of registration and not those on larger projects where risks are more catastrophic.

As the scale of a conventional project grows, so too does the number of specialist managerial functions involved in its delivery. How do we architects view this growing number of specialisations? Does it broaden the range of functions that a practising architect can specialise in? Or does it create a plethora of new professions that will compete against architects for our existing functions? Do we grow as a profession in line with our industry, or do we continue to shrink, focused ever more unnaturally on design? ■

Kerwin Datu is a practising architect as well as a qualified urban and economic geographer.

ARCHITECTURE BULLETIN

_____

27

Pursuing public works

A CONVERSATION BETWEEN CALLANTHA BRIGHAm, ANdy FERGUS ANd TImOTHy mOORE

Callantha Brigham: I recently came across the work you have been doing on public works through Monash University in Victoria. It seems you started exploring this around the same time we were forming the Designers in Government (DiG) Group in NSW – what is your interest in the public sector and why do you think it’s important to teach in this space?

Andy Fergus: Around 95% of architects are working in the private sector. The demands of private clients can position us in direct tension with notions of quality and equity. We wish to highlight career pathways that sit outside

the typical trajectory of designing housing for the wealthy that can lead to a quality-built environment that is spatially, socially and economically inclusive and sustainable. At the moment, the concept of good design is associated with intervening in the market. At its best, this process has led to the leveraging of the largesse of private money to improve the public realm. At its worst, we have seen public land sold off, poor-quality public spaces, and underinvestment in public buildings.

Timothy Moore: A great place to start is the education of future architects about how they can intervene in market-driven urban development. Ask any architecture student why they studied architecture and you will find most have a civic responsibility at the core of their decision. The positive news is there is an uptick in opportunities to work with or for public sector agencies in strategic roles. These upstream roles could be city or state government architects, councillors, design advocates, design excellence managers, strategic designers, urban designers, project managers or advisors.

PRACTICE AN d m ATERIALIT y

mPavilion by After Future Practice. Photo: Casey Horsfield

28

AF: What’s less clear are the pathways to being an upstream designer. The subject and subsequent public events titled Public Work expose students (and the profession) to projects and policies that influence architecture for the public benefit, and suggest possible career pathways or at least understand the ways that their private careers will benefit from a knowledge of public policy and good design guidelines.

CB: Your work seems to be a call to action for professionals to consider alternate forms of practice which may not be the norm but might deliver on civic goals that many aspire to when they study architecture, landscape architecture or urban design. This is a quest I have been on for a long time – in 2009 I went to the US as part of a Byera Hadley Travelling Scholarship and looked at alternate models of community service in architectural practice. What do you think some of the opportunities and challenges are in this space?

AF: The public sector is a phenomenal place to learn skills to later transfer into the community sector. It allows architects and designers to be involved in ways of urban development they may not have been involved in before, such as deliberative development, community engagement, public advocacy, urban design and urban governance.

TM: Through the subject, we were also investigating what models can support the upstream designer beyond teaching its future practitioners. We looked to the UK’s Public Practice, which supports architects in the public sector. It started because the problem in London’s LGAs, was getting talent into it. They told us in a meeting that over 20 Australians reached out to them interested in starting Public Practice in this country. We knew there was a demand here.

AF: We wondered: What is the problem in Australia? From my experience, it’s not about getting talent into the sector. This was the catalyst to teach Public Works: to explore what the issues are. We found that there’s a lack of knowledge capture, and sharing knowledge, within the sector. There’s also a lack of a relationship between research and practice. We are interested in the ability to develop collective knowledge, transfer this knowledge, and make public practice more visible. One exceptional example of this is the book Designing the Global City by Robert Freestone, Gethin Davison and Richard Hu. It’s a cracker.

TM: And in doing all of this, we can upskill students to engage more comfortably across built environment disciplines, including urban design and planning. ■

Callantha Brigham is NSW Vice President of the Australian Institute of Architects and co-chair of the Designers in Government (DiG) group. She is the Rothwell Resident in Urban Design at the University of Sydney where she is undertaking research and teaching on ‘The Hidden Practice and Invisible Impact of Design in Government’.

Andy Fergus is the head of urban design at Assemble. He is also the advocacy lead at Urban Design Forum Australia, a not-for-profit organisation that supports public interest outcomes in our cities.

Timothy Moore s a senior lecturer at Monash University within the architecture department, founder of Sibling Architecture, and curator of Contemporary Design and Architecture/ Melbourne Design Week at the National Gallery of Victoria.

Public Works was a subject run at Monash University with Masters of Architecture students in 2021, as a pilot for what aspires to be a replicable, open-source program. The Designers in Government (DiG) group was also formed in 2021, it now has over 90 members. The NSW Government Architect and members of the designers in government group spoke about their work and practice as part of the 2022 Festival of Urbanism.

ARCHITECTURE BULLETIN

29

Is the competitive design process anti-competitive?

WORdS: mATILdA GOLLAN

Published in 2019, Designing the Global City, Design Excellence competitions and remaking of central Sydney provided an in-depth review of the mandated competitive design policy (CDP) introduced by the City of Sydney in 2000. In researching the book, the authors interviewed 60 stakeholders from the design, development and planning professions. They developed a comprehensive review of outcomes from the competitive design excellence process between 2000 and 2017 – the good, the bad and the ugly. The authors found that the competitive process had positive outcomes for the public; design quality is elevated through emphasis on design considerations from the outset, producing varied and innovative solutions. They found the variety and range of firms awarded commissions increased, inevitably leading to differing design aesthetics and approaches, shaping the built fabric of the city. Developers also benefitted from the process, with increased developer certainty on design direction, planning approval and development viability in the early stages of the project. On speaking with architects, a legislated peer review design process was noted as the primary benefit to the profession, rather than any built outcomes. The authors found these significant benefits came at a cost, and that cost was shouldered by architects and developers.

While these costs were generally considered by developers to be offset by the benefits brought by the process, architects on the whole did not. In the years since this book was published there

has been some time to consider if the current system is still providing the public benefits identified and whether the negative impacts on architectural practices have been removed or reduced.

If we are to examine arguably one of the prime benefits identified by the CDP, the increased diversity of practices winning work in the City of Sydney, we find that while there was initial improvement, this has stagnated. The research found that prior to the CDP there were close relationships between developers and specific architectural practices leading to an anticompetitive market. The CDP was lauded for unpicking these relationships, helping to ensure that architects are awarded on work-based best ideas rather than entrenched cronyism. The data collected between 2000 and 2017 made the spread of the diversity of practices clear. From 46 competitions there were 35 one-time winners and eight multi-winning practices. Since 2017 we see a reduction in this diversity. Between 2018 and mid 2022, 26 competitions were run through the City of Sydney CPD. There were 14 one-time winners and five multi-winning practices, with one practice winning four competitions alone. There may be several reasons for this reduced diversity, including established practices having the capacity to greatly out-resource less established practices, or practices being preferred by developers or authorities based on reputation and/or relationships. Alternatively, it’s possible that the designs in these cases were just, in fact, better. Regardless of the

PRACTICE AN d m ATERIALIT y 30

reason, there appears to be a dilution of the benefits of the CDP in promoting diversity of architectural practices and consequently design aesthetics and approaches.

The authors of Designing the Global City found the overwhelming negative outcome to be the cost to both the developers of running competitions and more expressly to participants of competitions. It is much lamented by architects participating in the competitive process that the financial burden of competing far exceeds the payments received for their participation, at times to an absurd degree. There have been some moves to combat this issue, for example, the City of Sydney, in the 2020 amendment to their CDP, included a minimum honorarium payment of $150,000 to competitors participating in a design competition for high-density development in Tower Cluster Areas. Presumably, this is to account for the complexities of such sites. However, as one member of a large multinational practice remarked this year, this sum “won’t cover the real costs”. One of the disadvantages of this prohibitive financial burden is that medium- to small- practices are unlikely to be competitive with their reduced capacity to resource a competition sufficiently, knowing that remuneration will fall short of expenditure. They also likely have fewer large projects from which profits can be used to offset the cost of competing.

Perhaps, there are alternate ways to better align the cost of competing and honorarium payments to competitors beyond simply increasing the minimum payments. This approach saddles developers with some of the financial load without really tackling the root cause. A better approach may be to cap submission deliverables so that the focus shifts from the number and quality of renders to the design ideas themselves. This could be done in a variety of ways such as capping the number of renders and pages in a submission as was done on the 55 Pitt St competition. A tighter definition of deliverables with stricter policing of adherence to these deliverables would likely assist in reducing the labour creep associated with the CDP. To effectively police such adherence, a pre-jury review to check for conformance to the deliverable brief may be required.

In a move that demonstrates recognition of limited diversity in competition participants, the City of Sydney has included in their 2020 amendment of their CDP, a requirement of at least one emerging architect competitor for developments in the Central Sydney Tower Cluster. While increasing diversity among participants should be seen as a positive step, it seems counterintuitive to make this mandatory on complex high-density projects, while not requiring the same entrant quotas on smaller, less complex projects. In addition, without changes to the competition process which limit the inherent advantages of a bigger workforce held by larger practices, it feels like a futile gesture. Perhaps it would be more useful to limit the number of competitions per year a practice can be invited to, and make the selection criteria of competitors more transparent ensuring a greater variety of practices are included.

Knowing that the pool of design competition winners is reducing in diversity and the issue of competition remuneration remains outstanding, we have to question whether the process has become anti-competitive. This process is clearly serving the public, developers and authorities having jurisdiction, but needs to change if it is to remain truly competitive, allowing for a diverse mix of practices on an equal playing field. ■

Matilda Gollan is an associate at Tzannes and Associates and has practiced in North America, the UK and WA and NSW. Her interests lie in placemaking and the contribution that our buildings can make to the quality of our urban experience. She is currently a sitting member of the Australian Institute of Architects communications committee.

ARCHITECTURE BULLETIN

31

A letter to competitions

WORdS: mATT CHAN

A love-hate relationship. We love to slave for ideas. In hope that our ideas will surpass the ideas of our competitors, in hope that we can win a commission beyond the confines of everyday practice, an opportunity to prove our agency, to punch so far above our weight that we become legendary. To compete and mix it up with the best offices in the world somehow legitimises our identity.

The intensity of production is almost addictive –as Bruce Mau once said, stay up late, because crazy shit happens when you stay up late. We’ve all done it, despite knowing it’s bad for us – it’s not sustainable for any period of time and it creates awful working conditions for staff, but man you can get a lot done in a short space of time. You get to dream up things that are simply not possible within the norms of usual practice and that’s what makes it so alluring, but very much in the moth to the flame kind of way.

POWERHOUSE PARRAmATTA

Despite being in practice for nearly 20 years, being branded as an emerging architect has its perks. In this case, the two-stage international competition for the Powerhouse Parramatta required a creative collaboration between established and emerging talent. Naomi Milgrom AO, business leader, philanthropist and patron, was selected as the competition chair. Her longstanding interest in progressing the architectural conversation was key in bringing emerging practices into the limelight. It was by design that we as a small practice, had the opportunity to compete with the biggest and baddest offices in the world, and that emerging practice Moreau Kusonoki (France), with Genton (AU) would eventuate as the bright young

winners of this contest. Importantly, it gives agency to emerging practices at a scale that is otherwise impossible, putting their ability to generate ideas before their sheer capacity for delivery. It means the usual big-name offices’ success is not a fait accompli, and a voice is given to lesser-known practices that are wholly capable of engaging with the design process at this level.

As the biggest competition Sydney has seen for a long time, Powerhouse Parramatta created a maelstrom among the die-hard competition hunters. It was a nationwide jostle for a team that could boast it was the most emerging, most capable, and most interesting all at the same time. We figured almost certainly there would be teams representing Europe, North America, maybe Japan. Instead, we decided to back the wild-card entry of South America and teamed up with a Brazilian office from Rio de Janeiro, Bernardes Architectura (with Agencia), whom we knew nothing about, but at least liked their work a lot.

Stage 1 – The ugly pdfs

We hobbled together a submission back and forth across a diabolical combination of time zones, naively thinking that working across the world in these hyper-connected days would be easy. We thought our chances of being shortlisted were so slim that it didn’t matter anyway. And then we received that late call from Brazil saying “we’ve been shortlisted with our ugly pdfs!” As one of five internationally shortlisted teams, it was like winning the golden ticket. We couldn’t lose, because in our minds, we had already won.

Stage 2 – When my baby smiles at me, I go to Rio