16 minute read

Fastcase Fast Facts

By Cathy Underwood

In the last column, we talked about the difference between searching and browsing, and how to choose specific jurisdictions. (Remember that when you first enter Fastcase, “Current Sources” is set to the Entire Database.) But most of us are usually interested in only certain jurisdictions. For instance, as Arkansas attorneys, we are generally interested in Arkansas cases and statutes, and maybe Eighth Circuit or U.S. Supreme Court cases. For convenience, we would like that always to be the selected scope in the opening screen of Fastcase; we want it to be our “default scope.” To set a default scope requires three simple steps: (1) select the jurisdictions; (2) save it; and (3) set as default.

Advertisement

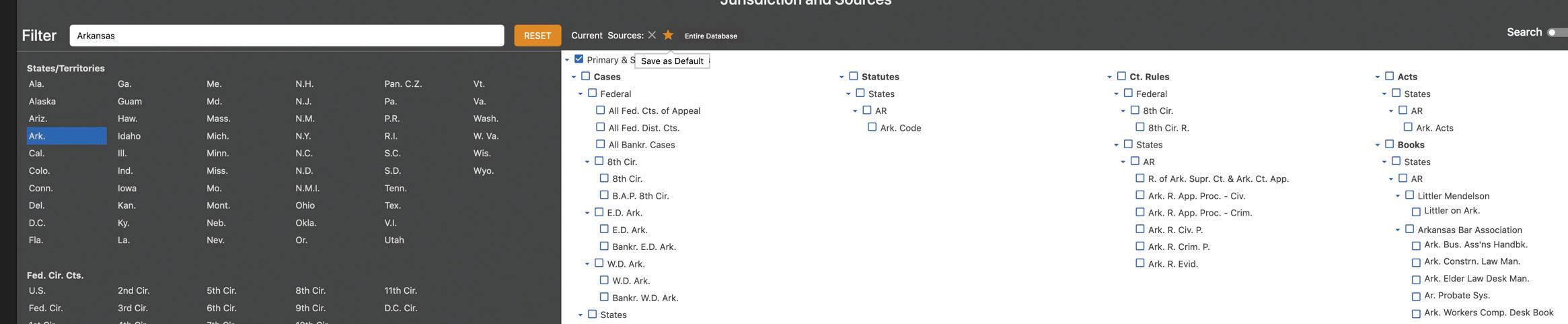

In Fastcase, click on “Jurisdictions and Sources” to the right of the search bar. (Remember you can also get there by clicking on the cog on the far right, and then choosing “Jurisdiction and Sources.”) Here’s what your screen looks like:

Notice that on the right side, all the primary and secondary law is listed. Here you can drill down to the jurisdictions you want, and click in the boxes to add them to your search. Or, on the left side of the screen, click on “Ark.” to limit your options to a more relevant list. (Note that sometimes there is a delay of just a few seconds. At first, this led me to think it wasn’t working, so be patient!) Now, your screen looks like this:

Cathy Underwood has provided editing services to ArkBar for over 35 years, and provides training to its members on Fastcase and ArkBar Docs. Join the Fastcase User Forum in the ACE Community

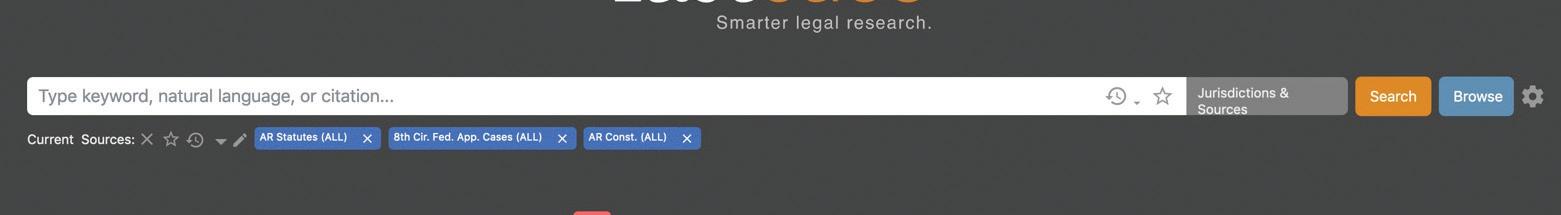

Now the options for Arkansas and Eighth Circuit are all open on your screen, ready to be clicked. Click on each item you wish to add to your search–you can mix and match them however you like. Note that if you want to add U.S. Supreme Court cases, you will have to go back to the left side, click “U.S.,” then select that option on the right.

Now that you’ve selected your sources, the next step is to save the selection. The easiest way to do this is before you leave the “Jurisdiction and Sources” screen. Notice near the top to the right of “Current Sources” there is an x and then a star. Hover over the star and a popup appears that says “Save Source.” Click once to save the source, then click again immediately to save as your default search. Note - If you hesitate too long before your second click in this process, you lose the ability to save as default this way. No worries! Click on the cog to the right of the search bar to get to “Advanced Search Options.” Choose the tab that says “Saved Sources.” This lists every source you have ever saved. Find the one you want, and hover your mouse on the right side of it. Options will pop up to “Apply to Search,” “Set as Default,” or “Delete this Source.”

Click on “Set as Default,” and you’re done! The next time you come back to Fastcase, “Current Sources” will show your personal default selection.

RICHARD MAYS LAW FIRM, PLLC

Richard H. Mays, formerly of Williams & Anderson PLLC, has relocated his office to 2226 Cottondale Lane, Little Rock (adjacent to the Arkansas Bar Center), and will continue his practice with emphasis on:

Environmental Law Oil, gas and natural resources law Eminent domain Flooding and Levees General litigation Real Estate and Business transactions

Richard Mays represents individuals, citizens groups and environmental organizations in cases against governmental agencies, such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Federal Highway Administration, and companies such as electrical utilities, oil and gas production companies, and national pipeline companies regarding private and public-works projects harmful to landowners and the environment of Arkansas.

Richard Mays Law Firm Over fifty years of fighting for the environment and the rights of individuals. Referrals welcome.

2226 Cottondale Lane • Suite 100 • Little Rock, AR 72202 • 501-891-6116 • rmays@richmayslaw.com

ARKANSAS OWNED AND OPERATED

info@facilicominc.com

THE SELECTED TELECOMMUNICATIONS PROVIDER OF THE ARKANSAS BAR ASSOCIATION

By Kyle Ward and Larry J. Thompson

Ward

Thompson

Kyle Ward is a law clerk at Matthews, Campbell, Rhoads, McClure & Thompson, P.A. in Rogers. Larry J. Thompson is an attorney in the firm who specializes in family law, mediation and arbitration.

Summary

In November 2018, the court in Raymond v. Kuhns ruled on a custodial relocation case involving joint custody between two parents. 1 The court may have overturned years of established Arkansas case law on custodial relocation. This article will give a brief background on Arkansas custodial relocation, how sole and joint custody cases differ, and why there is conflicting law that could cause major issues for Arkansas lawyers.

Why is Custodial Relocation Important?

Custodial relocation is a complicated issue in Arkansas. The right to travel and relocate between states is a fundamental right dating back to the Articles of Confederation. 2 However, the parent’s right to relocate must be balanced with the best interest of the child. 3 When addressing the best interest of the child, Arkansas courts have considered moral fitness, stability, love and affection, and family relationships. 4 The court’s main objective in resolving child custody disputes is to achieve the best interest of the child. 5

Sole Custody

Complicated sole custody relocation cases involve a primary custodial parent moving to another state with the child. The burden of proof in Arkansas custody relocation cases has shifted over time.

The court in Staab v. Hurst addressed whether geographical distance effectively denied visitation to the non-custodial parent. The case concluded that the custodial parent has the burden of demonstrating some real advantage will result to the new family unit from the move. 6 The primary parent needs to prove that this relocation is

in the child’s best interest and will benefit the family long term. 7 In order to determine why the relocation is in the best interest of the child, the court created a five-part test: “(1) the prospective advantages of the move in terms of its likely capacity for improving the general quality of life for both the custodial parent and the children; (2) the integrity of the motives of the custodial parent in seeking the move in order to determine whether the removal is inspired primarily by the desire to defeat or frustrate visitation by the non-custodial parent; (3) whether the custodial parent is likely to comply with substitute visitation orders; (4) the integrity of the non-custodial parent’s motives in resisting the removal; and (5) whether, if removal is allowed, there will be a realistic opportunity for visitation in lieu of the weekly pattern which can provide an adequate basis for preserving and fostering the parent relationship with the non-custodial parent.” 8

In Hickmon v. Hickmon, the court used the Staab factors for custody relocation. Here, the custodial mother could only prove the move was advantageous to herself. 9 The mother argued that the move was in the best interest of her daughter, she had other children who got along with her daughter, and her new position allowed more time to spend with her daughter. 10 However, these claims were not strong enough to overcome the experts’ opinions that this move would not be in her daughter’s best interest. 11

The Hollandsworth Presumption

However, the reasoning in Hollandsworth v. Knyzewski caused a major shift in this area of law because it essentially overturned cases that came before it. Hollandsworth shifted the burden of proof to the non-custodial parent, making that parent responsible for showing the move was not in the best interest of the child. 12 The Hollandsworth presumption allows the trier of fact to assume that relocation is not a material change in circumstances and that the custodial parent has the right to move with the child. 13

This is a direct change from Staab where the burden was on the custodial parent to justify an out-of-state relocation. 14 The custodial parent no longer needs to prove a “real advantage” to himself or the child. 15 However, the court will consider the following nondeterminative factors for the best interest of the child: “(1) [the] reason for relocation; (2) the educational, health, and leisure opportunities available in the location in which the custodial parent and children will relocate; (3) [the] visitation and communication schedule for the non-custodial parent; (4) the effect of the move on the extended family relationships in the location in which the custodial parent and children will relocate, as well as Arkansas; and (5) [the] preference of the child, including the age, maturity, and the reasons given by the child as to his or her preference.” 16

Then came Stills v. Stills. This case is unique because it dealt with a provision in the divorce decree that attempted to waive the Hollandsworth presumption. The divorce decree required the children to stay in northwest Arkansas until majority and the wife voluntarily waived her Hollandsworth rights. 17 Therefore, the wife had the burden to prove that relocating was in the best interest of her children. 18 The court found that the waiver was unenforceable because the presumption is not a “right” that may be claimed, waived or altered by one party or another, even through mutual agreement. 19 The court further “found that she had legitimate employment-related reasons for relocating; and that she was not relocating for purposes of diminishing the father’s involvement with the children.” 20

However, was this the correct analysis of prior case law? Unlike the court’s ruling in Stills, fundamental rights are subject to a waiver. 21 In his dissent, Justice Brown makes a strong argument that the parties in Stills referred to the burden of proof and not the determination of the best interest of the child. 22 This waiver “did not change that ultimate determination; it simply shifted the burden of proof from [the ex-husband] to [the exwife], a concession [the ex-wife] very likely made so that [the ex-husband] would not fight for primary custody of the children.” 23 This was a simple agreement by both parties that the ex-wife would have to prove her case for relocation. The majority may have incorrectly concluded that the Hollandsworth presumption cannot be expressly waived.

Joint Custody

The courts have applied a different line of reasoning in joint custody cases. Unlike sole custody, the Hollandsworth presumption does not apply to joint custody because both parents share equal time; there is not one parent-child relationship that takes preference over the other. 24

Singletary Analysis

Instead of Hollandsworth, Arkansas courts apply the reasoning from Singletary. The court in Singletary ruled that relocation is considered a factor in the material change of circumstances analysis and the burden does not fall solely on the non-primary parent. 25 In a change of custody request, courts will first determine whether a material change in circumstances has occurred and then determine if the relocation is in the best interest of the child. 26 Cooperation is also at the core of joint custody relocation cases. 27 If cooperation is disrupted by one of the parents, this could be grounds for a material change of circumstances. 28

After this case, the courts started weighing the reasons for relocation and clarifying how the Hollandsworth presumption was related to joint custody. The court in Cooper v. Kalkwarf clarified the division of time between parents in a joint custody situation. The court realized that a true “50/50” division of time by each parent is not precise in joint custody arrangements and limited the Hollandsworth presumption to situations where the child spends significantly less time with the alternate parent. 29 For example, a “60/40” division of time may still require a joint custody analysis under Singletary as long as the child does not spend significantly less time with one parent.

Was the Hollandsworth Presumption Incorrectly Applied?

Recently, the decision from Raymond v. Kuhns has muddled Arkansas custody relocation law. Here, the parents shared joint legal custody and the wife with primary physical custody wished to move from Arkansas to Kentucky. 30 The husband conceded that this was a material change in circumstances but disputed whether this was in the best interest of the children. 31 He claimed that the Hollandsworth presumption did not apply to joint custody cases and that the court should view the evidence in a manner more favorable to him. 32 However, the court ruled for the wife because the best interest factors from the Hollandsworth presumption still

apply in joint custody cases. 33 The wife established the Hollandsworth best-interest factors and spent a lot of time with her children in order to qualify for this relocation. 34

However, does this ruling overturn the Hollandsworth presumption and will Arkansas courts apply the rule incorrectly? The court in Raymond stated that while the presumption does not apply to joint custody, the best interest factors are relevant considerations. 35 It could be argued that the court in Raymond misunderstood how the presumption works because the entire presumption is built upon the factors in Hollandsworth. Essentially, the presumption in favor of the custodial parent is intertwined with relocation factors for only sole custody cases. This court has incorporated the presumption in joint custody cases by applying the factors without the presumption. This is conflicting and could be problematic for future rulings.

Additionally, what happens in counties where the visitation schedules are essentially a “60/40” split for both joint and sole custody? In Benton and Washington County, the visitation schedule for joint and sole custody parents is a “64/36” split which is reasonably close to a “60/40” split. Since the court in Raymond stated that the Hollandsworth factors and not the Hollandsworth presumption are applied in joint custody cases with essentially a “60/40” split, this decision could also influence sole custody cases with a “60/40” split. 36 In counties like Benton and Washington with a “60/40” split, the court in Raymond may have eradicated the Hollandsworth presumption. Now, the custodial parent may have to prove that it is in the best interest of the child to relocate instead of the non-custodial parent rebutting the presumption in favor of the relocation. Assuming the above analysis is correct, courts may continue to use the flawed reasoning in Raymond causing major contradictions in the law. It will be hard to predict how courts will rule in the future because not many cases have dealt with custody relocation since the Raymond case.

Conclusion: How Will Arkansas Courts Rule in Future Cases?

It will be important for future courts to clearly define this law to avoid conflicting opinions. Arkansas custody relocation cases should require different standards and analyses for sole and joint custody. However, it is now unclear in sole custody situations if the Hollandsworth presumption favors the custodial parent. Similarly, joint custody law is just as complicated. While the Singletary analysis eliminates the burden of the Hollandsworth presumption, the court in Raymond ruled that the Hollandsworth best interest factors still apply for relocation, allowing for potential conflicts in sole and joint custody situations. 37 As an Arkansas family lawyer, it is important to note that there are nuances in this body of law that could cause major problems in future custody cases. Today, the courts should implement a case-by-case analysis on the standard for joint and sole custody issues.

Endnotes

1. Raymond v. Kuhns, 2018 Ark. App. 567, at 1, 566 S.W.3d 142, 143. 2. Saenz v. Roe, 526 U.S. 489, 501 (1999). 3. Hollandsworth v. Knyzewski, 353 Ark. 470, 486, 109 S.W.3d 653, 664 (2003). 4. Singletary v. Singletary, 2013 Ark. 506, at 12, 431 S.W.3d 234, 242. 5. Staab v. Hurst, 44 Ark. App. 128, 133, 868 S.W.2d 517, 519 (1994). 6. Id. at 134, 868 S.W.2d at 520. 7. Id. at 135, 868 S.W.2d at 520 (holding that the opportunity for the custodial parent to achieve a better lifestyle should not be forfeited solely to maintain visitation when there is the possibility for a reasonable alternative to the existing visitation schedule for the non-custodial parent). 8. Id. at 134, 868 S.W.2d at 520. 9. Hickmon v. Hickmon, 70 Ark. App. 438, 438, 19 S.W.3d 624, 629 (2000). 10. Id. 11. Id. at 438, 19 S.W.3d at 630. 12. Hollandsworth, 353 Ark. at 485, 109 S.W.3d at 663. 13. Id. at 484-85, 109 S.W.3d at 663; Tidwell v. Rosenbaum, 2018 Ark. App. 167, at 7, 545 S.W.3d 228, 232 (holding that “the Hollandsworth presumption should be applied only when the parent seeking to relocate is not just labeled the ‘primary’ custodian in the divorce decree but also spends significantly more time with the child than the other parent”). 14. Staab, 44 Ark. App. at 134, 868 S.W.2d at 520. 15. Hollandsworth, 353 Ark. at 484, 109 S.W.3d at 663. 16. Id. at 485, S.W.3d at 663-64. 17. Stills v. Stills, 2010 Ark. 132, at 2-3, 361 S.W.3d 823, 825. 18. Id. 19. Id. at 9, 361 S.W.3d at 829; Acre v. Tullis, 2017 Ark. App. 249, at 6, 520 S.W.3d 316, 321 (holding that parents cannot agree to waive or alter the Hollandsworth presumption). 20. Stills, 2010 Ark. 132, at 14, 361 S.W.3d at 831. 21. Eubanks v. Humphrey, 334 Ark. 21, 28, 972 S.W.2d 234, 237 (1998); Rownak v. Rownak, 103 Ark. App. 258, 262, 288 S.W.3d 672, 675 (2008) (citing Am. Ins. v. Austin, 178 Ark. 566, 11 S.W.2d 475 (1928)) (holding that there is “the long-held right allowing parties to make their own contract and to fix its terms and conditions, which will be upheld unless illegal or in violation of public policy”). 22. Stills, 2010 Ark. 132, at 20, 361 S.W.3d at 834. 23. Jarica L. Hudspeth, Case Note, Stills v. Stills: A Perplexing Response to the Effect of Relocation on Child Custody, 64 Ark. L. Rev. 781, 794 (2011). 24. Tidwell, 2018 Ark. App. 167, at 6-7, 545 S.W.3d 228, 232. 25. Singletary, 2013 Ark. 506, at 12, 431 S.W.3d 234, 241-42; Raymond v. Kuhns, 2018 Ark. App. 567, at 10, 566 S.W.3d 142, 147 (holding that the Hollandsworth presumption does not apply but the best interest factors can be relevant considerations in joint custody cases). 26. Singletary, 2013 Ark. 506, at 9, 431 S.W.3d at 240. 27. Lewellyn v. Lewellyn, 351 Ark. 346, 356, 93 S.W.3d 681, 687 (2002). 28. Id. 29. Cooper v. Kalkwarf, 2017 Ark. 331, at 16, 532 S.W.3d 58, 67. 30. Raymond v. Kuhns, 2018 Ark. App. 567, at 1, 566 S.W.3d 142, 143. 31. Id. at 4, 566 S.W.3d at 144. 32. Id. at 10, 566 S.W.3d at 148. 33. Id. 34. Id. 35. Id. 36. Id. at 10, 566 S.W.3d at 147. 37. Singletary, 2013 Ark. 506, at 12, 431 S.W.3d at 241-42; Raymond, 2018 Ark. App. 567, at 10, 566 S.W.3d at 147.

Justice alert: and Pigmentary Maculopathy Litigation Elmiron

We help injured parties seek justice.

211 S. Spring Street Second Floor Little Rock, AR 72201 (501) 372-0038 david@dhwlaw.net dhwilliamslawfirm.com