Lawyer The Arkansas

ARKANSAS BAR ASSOCIATION 127th President

Kristin L. Pawlik

PUBLISHER

Arkansas Bar Association

Phone: (501) 375-4606 Fax: (501) 421-0732 www.arkbar.com

EDITOR

Anna K. Hubbard

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Karen K. Hutchins

PROOFREADER

Cathy Underwood

EDITORIAL BOARD

Caroline R. Boch

William Taylor Farr

Anton L. Janik, Jr.

Jim L. Julian

Tory Hodges Lewis

Drake Mann

Tyler D. Mlakar, Chair

Michael A. Thompson

Courtney K. Nosari Wall

Brett D. Watson

Amie K. Wilcox

David H. Williams

Nicole M. Winters

OFFICERS

President

Kristin L. Pawlik

President-Elect

Jamie Huffman Jones

Immediate Past President

Judge Margaret Dobson

Secretary

Glen Hoggard

Treasurer

Brant Perkins

Parliamentarian

Brent J. Eubanks

YLS Chair

Frank LaPorte-Jenner

BAR ASSOCIATION STAFF

Executive Director

Karen K. Hutchins

Director of Operations

Kristen Frye

Finance Administrator/CPA

Staci Clark

Director of Government Affairs

Leah Donovan

Publications Director

Anna K. Hubbard

Executive Administrative Assistant

Michele Glasgow

Office & Data Administrator

Cynthia Barnes

Professional Development Coordinator

Lisa McCormick

Information Specialist

Rachel Henderson

The Arkansas

Lawyer

features

2024-2025 Arkansas Bar Association

President Kristin L. Pawlik By Anna Hubbard

Photography by Mike Pirnique

The FTC's New Rule Banning Noncompetes: How to Help Employers Going Forward By Anthony McMullen and Dylan Botteicher

Between a Rock and a Set of Billing Guidelines By Gordon S. Rather, Jr.

Choice of Law and the Attorney-Client Privilege: Thinking Before You Speak By William A. Waddell, Jr.

Common Pitfalls in Enforcing Arbitration Agreements in Arkansas By Matthew Swindle

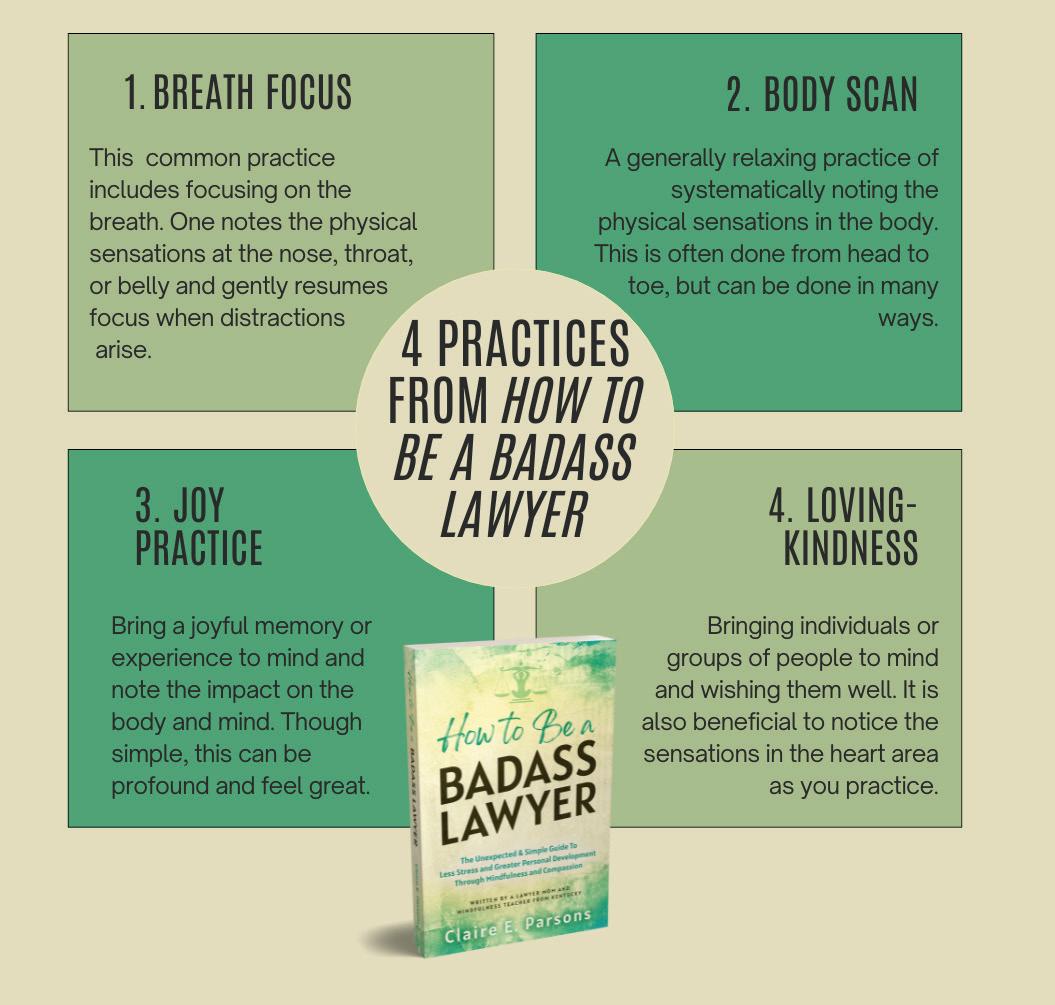

How Meditation Helped Me Become the Lawyer I Always Wanted to Be and Never Expected to Be By Claire E. Parsons

The Arkansas Lawyer (USPS 546-040) is published quarterly by the Arkansas Bar Association. Periodicals postage paid at Little Rock, Arkansas. POSTMASTER: send address changes to The Arkansas Lawyer, 2224 Cottondale Lane, Little Rock, Arkansas 72202. Subscription price to nonmembers of the Arkansas Bar Association $35.00 per year. Any opinion expressed herein is that of the author, and not necessarily that of the Arkansas Bar Association or The Arkansas Lawyer. Contributions to The Arkansas Lawyer are welcome and should be sent to Anna Hubbard, Editor, ahubbard@arkbar.com. All inquiries regarding advertising should be sent to Editor, The Arkansas Lawyer, at the above address. Copyright 2024, Arkansas Bar Association. All rights reserved.

Contents Continued on Page 2

Lawyer The Arkansas

Advertise in the next issue of The Arkansas Lawyer magazine

President: Kristin L. Pawlik; President-Elect: Jamie Huffman Jones; Immediate Past President: Judge Margaret Dobson; Secretary: Glen Hoggard; Treasurer: Brant Perkins Parliamentarian: Brent J. Eubanks; YLS Chair: Frank LaPorte-Jenner

Trustees:

District A1: Elizabeth Esparza, Geoff Hamby, William M. Prettyman, Lindsey C. Vechik

District A2-A3: Matthew Benson, Evelyn E. Brooks, Jason M. Hatfield, Christopher M. Hussein, Michelle Rene' Jaskolski, Sarah C. Jewell, George Rozzell, Russell B. Winburn

District A4: Kelsey K. Bardwell, Craig L. Cook, Brinkley B. Cook-Campbell, Dusti Standridge

District B: Randall L. Bynum, Mark Kelly Cameron, Thomas M. Carpenter, Tim J. Cullen, Bob Edwards, John A. Ellis, Bobby Forrest, Michael K. Goswami, Steven P. Harrelson, Michael M. Harrison, Jim Jackson, Anton L. Janik, Jr., Victoria Leigh, Skye Martin, Kathleen M. McDonald, J. Cliff McKinney II, Jeremy M. McNabb, Molly M. McNulty, Meredith S. Moore, John Ogles, Casey Rockwell, Lauren Spencer, Aaron L. Squyres, Caitlin Campbell Stepina, Jessica Virden Mallett, Danyelle J. Walker, Patrick D. Wilson, George R. Wise

District C5: William A. Arnold, Joe A. Denton, John T. Henderson, Brett D. Watson

District C6: Bryce Cook, Paul N. Ford, Jeffrey W. Puryear, Paul D. Waddell

District C7: Kandice A. Bell, Robert G. Bridewell, Sterling T. Chaney, Taylor A. King

Delegate District C8: Carol C. Dalby, Amy Freedman, Connie L. Grace, John S. Stobaugh

Ex-officio Members: Judge Ken Coker, Judge Chaney W. Taylor, Vicki S. Vasser, Dean Cynthia Nance, Dean Colin Crawford, Denise Reid Hoggard, Eddie H. Walker, Jr., Christopher M. Hussein, Karen K. Hutchins

Strength & Guidance

Oyez! Oyez!

APPOINTMENTS AND ELECTIONS

Skye Martin has been elected chair of the Access to Justice Commission; Rose Law Firm announced that Dan C. Young has been invited to be a Fellow of the American Bar Foundation.

WORD ABOUT TOWN

Amy Tracy has opened Tracy Law, PLLC emphasizing transportation law and small business general counsel services. Claire Cockrell, a graduating student at the William H. Bowen School of Law, expects to begin her career in law as assistant district counsel for the east district of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in Pyeongtaek, South Korea. Hall Booth Smith is pleased to welcome partner Randal B. “Randy” Frazier and attorney Jacob Oneal Sutter to its Little Rock office. Hosto & Buchan Law Firm announced that Kellie Loftis and Joshua Jackson have joined the firm in their Little Rock offices. Community First Trust (CFT) announced the appointment of Thomas Smith as General Counsel of Trust & Wealth Management. Cozen O’Connor announced that Dustin McDaniel will co-chair the State Attorneys General Group. McDaniel Wolff PLLC announced that Adam Conrady joined the firm as an associate.

Send your oyez to ahubbard@arkbar.com

Lawyer

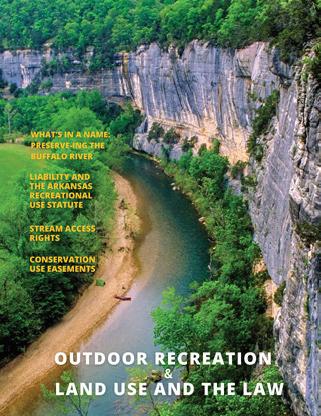

The Arkansas Bar Association’s flagship publication, The Arkansas Lawyer, received the Excellence in Communication Award for the Spring 2024 issue “Outdoor Recreation and Land Use and the Law” from the Arkansas Society of Association Executives.

The Arkansas

Modeling Civility and Empathetic Advocacy to

Protect the Rule of Law

Lawyers, as guardians of the rule of law, are experiencing a pivotal moment as we witness daily the escalating political rhetoric and vitriol. Horrific attacks on elected officials, casual suggestions of violence woven into stump speeches, and the very real attacks on the judiciary continue to shake the very foundations of our democracy and the principles of justice that we have sworn to uphold. In these times, it is critical to reflect on the values that define our profession. We are stewards of justice, advocates for the rule of law, and guardians of the principles that underpin our democratic society. I recently spoke of the crucial role of civility and empathetic advocacy in an address to our members at the Annual Meeting. These concepts are not merely aspirational ideals; they are essential to the functioning of our legal system and the preservation of public trust in our institutions.

The Erosion of Civility

Civility in the practice of law transcends mere politeness; it embodies the respect, dignity, and professionalism that are essential for a functioning legal system. Historically, lawyers have been experts at crafting insults.1 But the cloak of anonymity on social media sites—especially X and Facebook—fuels a battlefield for digital drone strikes. The attacker can sit comfortably from a distance and dispense hostilities without ever looking in the eyes of the recipient. This trend has seeped into the legal community online, and erodes public trust in our legal institutions.

Members of the Arkansas Bar Association must recommit to upholding civility in all aspects of our practices. This commitment includes treating all participants in the legal process with respect, listening actively and empathetically to opposing viewpoints, and refraining from hostile behavior.

Kristin Pawlik is the President of the Arkansas Bar Association. She is a partner at Miller, Butler, Schneider, Pawlik & Rozzell, PLLC in Northwest Arkansas.

The Power of Empathetic Advocacy

Alongside civility, empathetic advocacy is crucial in our efforts to serve justice. This past June, former Governor Mike Beebe reminded a crowd of lawyers gathered to celebrate the centennial of the University of Arkansas School of Law that we are trained to be empathetic. Remember, in law school, we learn to form effective arguments by considering the positions of all the stakeholders. Of course, the ancient practice of seeking to understand is also pragmatic, because when we understand the perspectives of opposing parties we can tailor our arguments more effectively to increase the likelihood of a favorable outcome.2

Empathy enhances our ability to persuade. But it is also possible that by practicing empathy, we demonstrate that lawyering is not solely about winning cases. Those of us who practice family law understand that a slash-and-burn approach to litigation—while satisfying the keen competitiveness that brought many of us into the practice of law in the first place— usually causes irreparable damage to the family members after the divorce or custody ruling.Tapping into our empathy allows us to anticipate and address concerns that remain after the gavel falls.

Defending the Judiciary and Protecting the Rule of Law

The recent attacks on the judiciary are alarming to us all. We know that an independent judiciary is fundamental to our democracy, ensuring that justice is administered impartially. When the judiciary is undermined, the very fabric of our legal system is at risk. As members of the bar, we have a special responsibility to defend the judiciary and uphold the rule of law. So how do we take that critical message to our communities?

Start by speaking out against unjust criticism and baseless attacks on judges and the judicial process. Look for opportunities to educate the public about the vital role of the judiciary in maintaining the balance of power and protecting individual rights. Most importantly, our responsibility to defend and protect means that we broadcast to those around us that we are lawyers, that our profession is noble, and that we believe in this fragile yet remarkable system of justice.

A Call to Action

So let us reaffirm our commitment to civility and empathetic advocacy. Let us lead by example, demonstrating that it is possible to advocate passionately while respecting our opponents. In our law practices, let us be voices of reason and compassion. Demonstrate that civility and empathy are not signs of weakness, but of strength. Save the snark for book club and pickleball.

Endnotes:

1. E.g. “I can explain this to you; I cannot comprehend it for you”; former New York City Mayor Ed Koch, to journalist Andrew Kirtzman on “Inside City Hall.” U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Melville W. Fuller, shortly before his death, after a conference attendee gave thanks to God “for his ignorance” replied, “Then you have a great deal to be thankful for.” “He can compress the most words into the smallest idea of any man I ever met”; President Abraham Lincoln describing a political opponent.

2. See also “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.” Tzu, S., The Art of War, (Capstone Publishing 2010); “Let the wise also hear and gain in learning, and the discerning acquire skill,” Proverbs 1:5, The Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version (1989). ■

YOUNG LAWYERS SECTION REPORT

Momentum

Frank LaPorteJenner is the Chair of the Young Lawyers Section. Frank is a managing partner of LaPorte-Jenner Law, PLLC.

The new year just started for the Young Lawyers Section and it’s already looking like it’s going to be our best yet. We just closed out the 126th Annual Bar Conference with our biggest social event ever thanks to the hard work of our previous chair Caroline Kelly. Now our goal is to carry that momentum forward and continue our mission of introducing new members to the Bar Association through fantastic social events and engaging volunteer opportunities. To make this our best year yet, however, I will need all the help I can get. We have a lot of big plans, and I hope you will reach out to volunteer, join us at a social event, or just share your ideas.

To start the year out, President Kristin Pawlik and I will be visiting both of the state’s law schools to meet with the newest 1L students at their orientation programs. The Bar Association is a resource to both attorneys and students, and YLS is here to start the school year strong. YLS has always provided networking opportunities to law students, and this year won’t be any different. Our plan is to host as many social events with the law students as possible. And once we have our events on the calendar, I’ll be asking everyone in the Bar Association to join us. It’s important for our organization to connect with students and new attorneys, so I’m counting on everyone to help me build those connections.

On the topic of our social events, we are already at work planning our main

networking events of the year: our mid-year conference party and our annual conference party. These two parties are some of the biggest events hosted by the Arkansas Bar Association, and if I want to live up to the 2023-2024 year I’ve got my work cut out for me. Fortunately, our 2024-2025 annual conference chairs are also past YLS Chairs, Mr. Chris Hussein (2019-2021) and Mr. William Ogles (2022-2023). These gentlemen know how to host a great party, so we will be in good hands working together. While social events are one great way to make connections, YLS will also be engaging in several outreach programs this year as well. One of our biggest volunteer opportunities is our Wills for Heroes clinic that we host in the spring. At this clinic we draft estate planning documents for first responders throughout the state of Arkansas. You’ll be getting an invitation to volunteer with us as we get closer to the spring, and I will also be reaching out to the law schools

to invite students to join us for this and our other pro bono programs.

Unfortunately, I don’t have enough space on this page to go through everything that we have planned for the upcoming year. What I hope that you take away from this report, however, is how important your engagement will be. For us to help build meaningful professional relationships, we need our members to be present and meet the newest group of students and attorneys joining our organization. For our outreach programs to succeed, we need our members to show up and give back. If you are interested in putting together an event or being a co-sponsor for one of our programs, please don’t hesitate to reach out anytime. We have an ambitious year ahead of us, and I’m going to need your help to make it a successful one.

Frank owns and manages LaPorte-Jenner Law, PLLC with his wife Kelli, and can be reached anytime at frank@LPJlaw.com ■

2024-2025 YLS Executive Council (as of July 31, 2024)

Frank LaPorteJenner, Chair

Breanna Jordan McLaren Chief Engagement Officer

Justin W. Harper

District B. Rep.

William T. Harris

District C Rep.

Grace Wewers

Fletcher At-Large Rep.

Samuel W. Mason, Chair-Elect & District A Rep.

Brittany Hawkins District A Rep.

Dominique D. Lane Secretary/ Treasurer & At Large Rep.

Marcus A. Priest District A Rep.

Hayley Ferguson

District B. Rep.

Will Hegi District C Rep.

ArkBar Young Lawyers Section

Syndey L. Rasch

District B Rep.

Ledly S. Jennings

District C Rep.

@ArkBar YLS

Caroline Kelley passes the gavel to Frank

By Anna K. Hubbard

Proud to be a Lawyer

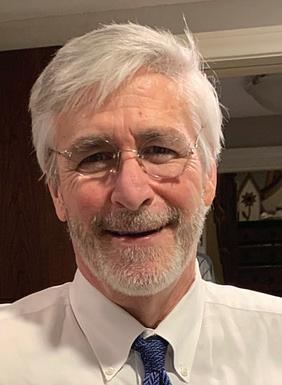

Arkansas Bar Association 127th President

Kristin L. Pawlik

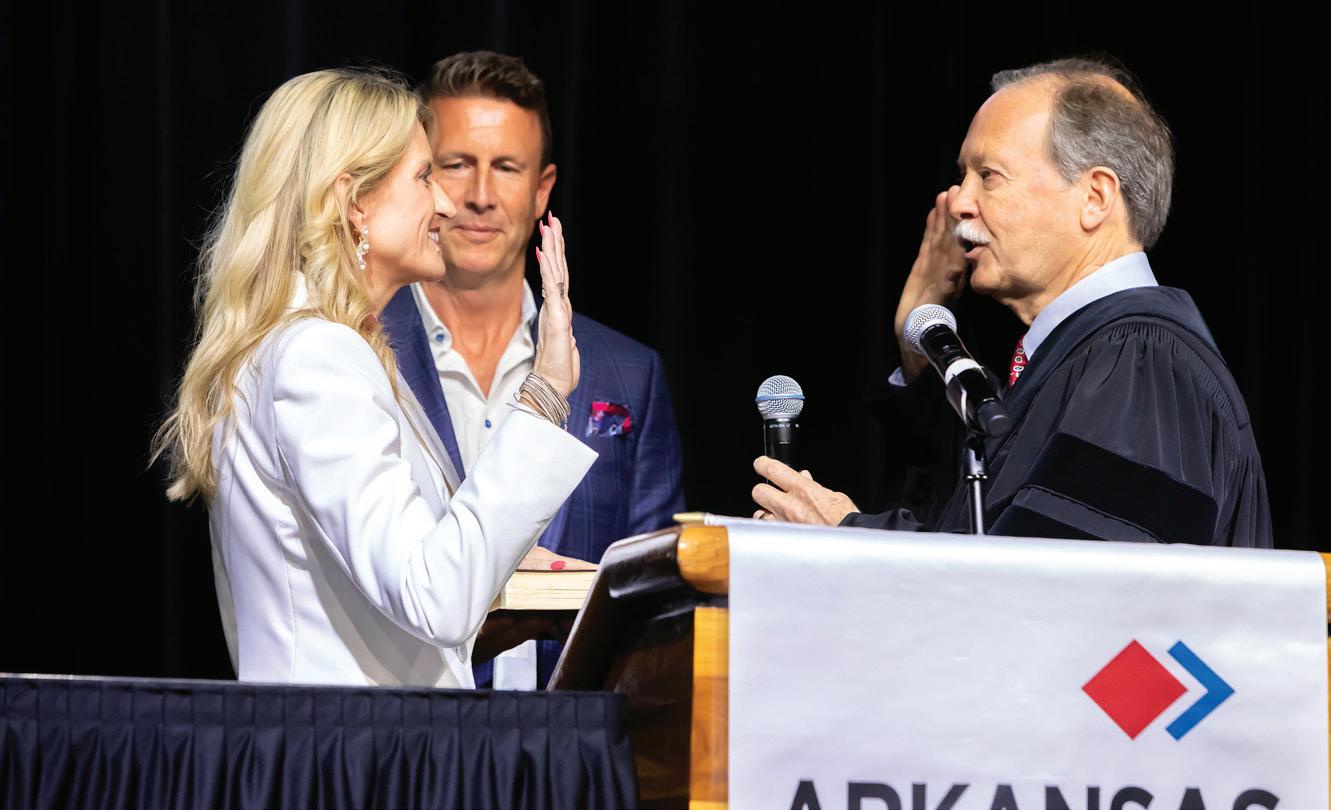

Kristin Pawlik was sworn in as president of the Arkansas Bar Association on June 14, 2024, during the Association’s Annual Meeting at the Hot Springs Convention Center. Chief Justice Dan Kemp performed the ceremony. Kristin is a partner at Miller, Butler, Schneider, Pawlik & Rozzell, PLLC in Northwest Arkansas. She litigates family law, criminal defense, and employment matters.

Kristin graduated from the University of Arkansas in 1996, where she received a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism with an emphasis in Public Relations. She attended law school in Fayetteville and received her Juris Doctor from the University of Arkansas School of Law in May of 1999. In 2001, she attended the National Criminal Defense College Trial Practice Institute at Mercer Law School.

When Kristin Pawlik introduces herself, she is quick to let people know what she does for a living. “I’m proud of my profession. I’m proud of what I chose to do. I want people to know that I’m a lawyer,” she said during her swearing-in remarks.

“What do I think being a lawyer says about me, or what do I hope it says about me? My kids would say, being a lawyer means mom thinks she’s always right. I am, of course, but that’s not what I’m processing. My husband would say that it means that I come home sometimes, and I cross-examine him. That is also true. And I’m sorry about that. A little. And my sister would say it means that I can’t help but give her advice, which she ignores. And that’s true too, all the time, for free. But what does being a lawyer say about me?

“I want it to mean I’m a helper. I’m a fixer. I can fix things. I can be your voice if you don’t have one. I’m a fighter. I’m a fighter when I need to be. I’m a patriot. I believe in our Constitution. I believe in the Constitution of the state of Arkansas. And I will fight and defend it. I’m a defender, I’m an ally, I’m a believer, I’m a change maker. Being a lawyer means you can be all those things. And I know that you are all those things in your communities, and it’s okay to lead with that.”

“I want people to ask me what to do, how to do it, how to fix it, how to make it right. Because I know that we can do those things. I know that I can do those things. I know that each of you have done those things. You will do those things and you’ll continue to try to fix it, try to make it right. So when you go back to your church or you go back to your pickleball game, or your POA meeting, library board, whatever, embrace it. I want you to lead with, I’m a lawyer, because it should mean all those things. And I want people who aren’t lawyers to remember that it does mean all those things. Because we could lose this great, beautiful, amazing justice system that we have if people don’t believe in it.

“Because that’s all it is. It’s believing in our system. That’s why those words are everywhere ‘we believe.’ So go back to your communities and take care of your people and take care of your clients and take care of each other—and protect the Rule of Law.”

Photography by Mike Pirnique

Community

Growing up in Bentonville, Arkansas, “before it was cool,” Kristin was raised in what was then a small town. Her father, Kevin Pawlik, was a lawyer who instilled in her the importance of practicing law within the community. He inspired her with his passion for the legal profession, showing her the importance of taking a position, arguing it effectively, speaking for those who were unable to, and standing up for people.

“My dad was very inspiring to me about loving the pureness of the law and the facts and the history. I learned from him what small town practice could feel like, and where the people who are your clients are also your neighbors. I don’t want to get away from that feeling of community as our small state, especially in my area, grows bigger and bigger.”

Chief Justice Dan Kemp performed the swearing-in ceremony for Kristin immediately following his State of the Judiciary Address. As Kristin remarked, “Justice Kemp talked about building the connections between the bench and the bar, but also, within the bar so that we all remember that we don’t just exist on opposite sides of the courtroom. You know, we exist in this room, and we exist as we’re sitting across the coffee table from each other and talking about the things we do agree on. And I’m grateful that we have this opportunity to come together at the annual meeting. We’re the only association of lawyers in Arkansas that is for all lawyers.”

Local Girl with Conviction

Kristin started her career as a public defender in Bentonville, where she served for over four years, most recently as the Chief Deputy Public Defender. She had been drawn to criminal law after working in the criminal clinic in law school where she had the opportunity to represent juveniles in court. “I really enjoyed representing these people who weren’t used to having someone take up for them and speak for them. There was a lot of appreciation from clients for treating their case very seriously and for advocating and fighting for them. It is a remarkable payoff doing that work.

“I was serving as chief deputy public defender when Drew Miller [her current law partner] called me and offered me a job. I had no intention of leaving until he came to see me. And now that I look back, I doubt I would’ve left for anybody else.”

Drew said that Kristin is one of the most amazing people that he knows. “She is truly an advocate for all the right reasons. I have always been struck with how much empathy toward people she has. When she was a public defender, I had the ability to observe her in the most difficult aspect our profession is honored to do. She did it with grace and conviction. She loved her job and it showed. Again, this compassion received no thanks, honors, and very little compensation. It was what she was born to do, represent those who truly need it, and need it done perfectly for them to survive.

“It was hard to not notice a local girl with that much conviction; she stood out. What I found when I started the process of hiring her was that she stood out in a lot of other ways, such as community involvement and family. I knew it would not be easy to get her to leave the job she loved, so I had to offer her an opportunity where she could continue to grow as an attorney, yet still have unlimited authority to help people. Additionally, I had to make sure she had the ability to put her family before being an attorney.”

“Her family has always been first in her eyes and her journey as an attorney is more remarkable given that fact,” Drew added. “The Arkansas Bar Association will only move to a better place based on the leadership she will provide. It will be thoughtful, proactive, and make the profession better as a whole. I will sit back and enjoy the show; it will be amazing.”

It Takes a Village

Kristin and her husband Aaron Holmes have three teenage boys, Jackson, Spencer and Wyatt. She credits Aaron’s skills as a consummate manager for giving her the support she needs. “He spends all day managing people at the shop where he works. And then he comes home and he manages me, which my partners know is a heck of a job. And he manages our boys, and he makes sure that I at least know where I’m supposed to be. And he still loves me when I’m not exactly on schedule. I’m very lucky and I know it.”

Pictured from left: Jackson, Wyatt, Kristin, Aaron and Spencer

She receives strong support from her sister, her in-laws and a great group of girlfriends. Living a mile from her sister is a blessing for the families. “I’ve got a village of people who have been really generous in helping me and in making sure that my kids feel loved and adored as they should.”

One of Kristin’s dear friends, Kerry Bradley, describes Kristin as a rock star. “Nothing rattles that girl. She is very calm, cool and collected.” Kerry is president of Garrison Asset Management of Fayetteville. “I try to be more like her when I get stressed, and think what would Kristin do? Whether it is traveling with kids, flight delays or anything.”

“She’s my adventure-loving friend. Together we have hunted scorpions, chased the Northern Lights, and fished down in the Caribbean.”

“She has been a sounding board for me for over two decades now,” Kerry added. “We are always bouncing things off each other, and I can always count on her for some great advice. She’s insightful and thoughtful. She is great at navigating difficult conversations in a very respectful manner. And she is always thinking about both sides.

“I think the Bar Association is in for a real treat with her leadership. She’s obviously very capable, as evidenced by her distinguished career and all her accomplishments. She’s not only a great lawyer, she’s a great friend. She’s a great leader, she’s a great human.”

Cooperative of Legal Thinkers

Kristin’s former partner Sean Keith encouraged her to become active in the Bar Association. Sean has been active in the Association for many years, serving as Chair of the Board of Governors and on numerous committees and task forces.

“Sean loves the Bar Association and believes in bar leadership and conveyed to me the importance of that. I saw from him that being active in the bar means that you’ve always got a connection.”

Sean has full confidence in Kristin’s leadership abilities. “No one multitasks better than Kristin Pawlik,” he said.

“Raising three sons with husband Aaron, a partner in a busy practice, and being a leader in her community could all be fulltime jobs. Her ability to simultaneously advise a divorce client, control her boys in the back seat of her minivan while driving to support a local community event is awe inspiring. There is only one KP and I feel very fortunate that she is willing to lead our Bar Association.”

Kristin said that it has been “immensely helpful in my practice to be a part of a cooperative of legal thinkers. I think it makes me a better lawyer, hearing the perspective of another fine attorney out there who might do something just a little differently, but it makes me look at the situation a different way. So, that’s really one of my favorite things about being involved

in the bar. And then the bar leadership just puts you in contact and helps you create relationships with the lawyers who are passionate enough about the profession to be involved. You’re really going to be spending time with people who care about the profession.”

Kristin took Sean’s advice to get involved and was appointed to some of the heaviestlifting committees of the Association. Her interest in politics (she was just an hour or two shy of a political science minor) steered her toward the legislation work of the Bar Association. She served on the Legislation and Jurisprudence and Law Reform Committees, the Legislative and Strategic Governance Task Forces, and the House Advisory Committee, and served as co-Chair of the Annual Meeting. ArkBar honored Kristin with a Golden Gavel Award for her work as co-chair of the 2022 Annual Meeting and a Golden Gavel Award in 2017 for her work as chair of the Legislation Committee. She was elected to serve ArkBar District A as a Trustee, and previously served on ArkBar’s Board of Governors and House of Delegates.

Immediate Past President Judge Margaret Dobson has worked closely with Kristin the last few years and values her leadership and friendship. “I love her!” Judge Dobson exclaimed. “Kristin’s unwavering poise, sharp wit, and steadfast integrity make her a remarkable colleague and friend. Her

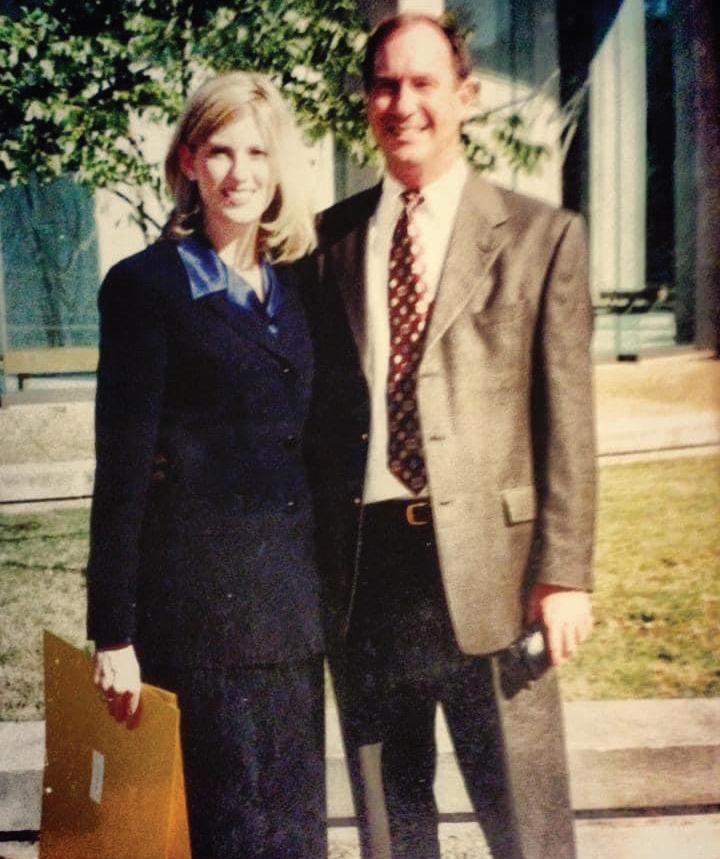

left photo: Kristin pictured with her father, Kevin Pawlik, at the swearing-in ceremony when she was admitted to the bar in 1999. Top photo: Kristin pictured with her husband, Aaron, and Chief Justice Dan Kemp at the ArkBar presidential swearing-in ceremony June 2024

wisdom and grace in handling even the toughest challenges inspire me. Plus, she is such a fun person. She is game to deliver food to the fire department, embrace the fun of the magic show, and answer my texts and emails at crazy hours. The only complaint I have about her is that she lives three hours away from me!”

In 2017, Kristin was chosen to represent the Arkansas Bar Association on the Arkansas Access to Justice Foundation Board where she continues to work for access to legal services for low-income Arkansans. She was appointed by both Governor Mike Beebe and Governor Asa Hutchinson to serve as Chair of the Arkansas Commission on Child Abuse, Rape and Domestic Violence. A Fellow of the American Bar Foundation, she is a past president of the Benton County Bar Association, as well as a member of the Arkansas Trial Lawyers Association and the Arkansas Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. Kristin is a past chair of the University of Arkansas Law Alumni Society and an alumna of Delta Delta Delta Sorority.

Kristin is very proud of her work with the Access to Justice Foundation. “Access to Justice is special because we’re helping Arkansans have access to legal services in Arkansas, and we are such a high-poverty state with such a low ratio of lawyers to citizens. We are always around the bottom

two percent in the country of lawyers who are available to help our citizens. Because of those two issues it is just incredibly important that we use every dollar of grant money from the IOLTA program in Arkansas to provide quality programming to help bridge that gap between the people who need the legal services and the legal counsel that’s out there.”

Modeling Civility

Kristin speaks about the importance of civility and believing in the justice system in her swearing-in remarks. “One of the things that the bar helps us with is creating all those opportunities for lawyers to spend time in the same room, to talk and visit and get to know each other, and talk about each other’s kids. And then, when you’re in a courtroom or in intense litigation, even if you are furiously advocating for your client, you still remember that the other side has a kid that plays on your son’s football team. Or maybe you are on a committee with that lawyer through the Bar. So, you remember that the relationships matter, that you’re going to see these lawyers again, and you’re going to interact with them and you’re going to need their help maybe, or their counsel. And that, again, is part of Arkansas being such a small state. So, I think that’s what lawyers can do at a basic level to improve civility.

Our mission, as Justice Kemp pointed out, is to protect the Rule of Law. We can do that by reminding citizens that our system exists for a purpose and believing that it is good for all of us, and that understanding each other is good for all of us. We may disagree, but we can be reasonable in our discussion. We can be kind in our disagreement. I would encourage you guys to take that out into your practice. Again, most of you already do; I’m just refreshing and reminding us.”

In Kristin’s column on page seven of this magazine, she asks lawyers to “reaffirm our commitment to civility and empathetic advocacy. Let us lead by example, demonstrating that it is possible to advocate passionately while respecting our opponents. In our law practices, let us be voices of reason and compassion. Demonstrate that civility and empathy are not signs of weakness, but of strength.”

“Thank you, the members of the Arkansas Bar Association, for your dedication to the practice of law, your embodiment of professionalism, civility and integrity and your commitment to protect the Rule of Law,” she added. ■

left photo: the lawyers of Miller Butler Schneider Pawlik & Rozzell PLLC right photo: Kristin being "crowned" during the magic show at the Annual Meeting

The FTC’s New Rule Banning Noncompetes: How to Help Employers Going Forward

By Anthony L. McMullen and Dylan Botteicher

Anthony L. McMullen is an assistant professor of business law at the University of Central Arkansas College of Business.

Dylan Botteicher is a partner at Cox, Sterling, Vandiver & Botteicher. His practice primarily focuses on employment and business litigation.

Introduction

In April 2024, the Federal Trade Commission announced a rule declaring noncompete clauses in employment agreements to be an unfair method of competition and ordering employers to rescind most of their agreements. This sweeping change may affect an employer’s ability to protect their interests after the termination of the employment relationship. This article discusses the current state of Arkansas law and the changes that will be made if the rule is allowed to go into effect. It concludes by suggesting steps that attorneys can take to counsel employers affected by the new rule.

The focus of this article is on noncompete clauses in employment agreements. Noncompetes are also often ancillary to the sale of a business, but the FTC rule is intended to affect only those clauses that are part of an employment relationship. Still, someone contemplating selling a business may wish to review potential agreements to ensure that any noncompete clause found therein does not fall within the scope of the new rule.

Summary of Arkansas Law

The Restatement (Second) of Contracts summarizes the common law as it relates to noncompete agreements. Generally, contract provisions that are unreasonably in restraint of trade are void and unenforceable as a violation of public policy.1 Further, any “promise to refrain from competition that imposes a restraint that is not ancillary to an otherwise valid transaction or relationship is unreasonably in restraint of trade.”2 However, noncompete agreements have typically been allowed if they were ancillary to the sale of a business or to an employment agreement.3 To be valid, however, any such agreement had to go no further than necessary to protect a legitimate business interest.4 Further, the agreement could still be invalidated if the need for the agreement was outweighed by the hardship to the promisor and was likely to injure the public.5

In 2015, Arkansas adopted Act 921, governing noncompetes in employment agreements.6 While many of the statute’s provisions mirrored common-law principles, such as requiring that such a clause be in place to protect a protectable business interest and go no further than

"The FTC’s new rule, if it goes into effect, will make it harder for employers to restrict their employees from working for a competing business at the end of the employment relationship. But even if the rule ultimately does not go into effect, now is a good time for attorneys to help employers review their agreements with employees and, if necessary, help them find other ways to protect their legitimate business interests."

necessary to protect that interest,7 other provisions were either substantial changes to Arkansas law or clarified things on which Arkansas law appeared to be silent.

First, before the enactment of Act 921, a noncompete clause found to be unreasonable would be nullified in its entirety.8 The language of Act 921 requires courts to reform overbroad noncompete clauses to make them reasonable and not impose a restraint greater than necessary to protect the employer’s protectable business interests.9

Second, Act 921 created a presumption that a noncompete clause lasting two years was presumptively reasonable, at least as it relates to the time restriction. This may not have been a major change, as a two-year term was fairly standard.10 Further, at least with respect to noncompetes ancillary to the sale of a business, Arkansas courts have previously enforced clauses with a five-year restriction, a 10-year restriction, a 20-year restriction, and even no time restriction.11

Finally, Arkansas law before the passage of Act 921 was unclear regarding the enforceability of noncompetes where there was no consideration given beyond continued employment. While many states require a noncompete clause to be supported by additional consideration to be enforceable,12 Arkansas joined the list of states where continued employment, by itself, was sufficient consideration for a noncompete clause.13

Despite the passage of Act 921, there are still judicial opinions that cite pre-Act 921 language. In Lamb & Associates Packaging, Inc. v. Best, 14 the court of appeals still stated that noncompete clauses “are not looked upon with favor by the law,” and further that noncompetes “in employment contracts are subject to stricter scrutiny than those connected with a sale of a business.”15 Still, the court applied Act 921 and ultimately held that the noncompete clause there

was unenforceable because the employer lacked a protectable business interest in the confidential information that it was seeking to protect.16

The New FTC Rule

In January 2023, the FTC sought comment on a rule to ban noncompete clauses.17 The proposed rule was part of the FTC’s renewed effort to enforce its authority to ban unfair methods of competition.18 Specifically, three months prior, FTC Chair Lina M. Khan issued a policy statement “rededicat[ing] ourselves to executing the full set of duties Congress tasked us with more than a century ago.”19 Khan stated that Congress’ intent in passing the FTC Act was to give the FTC the authority to “police the boundary” between fair and unfair methods of competition and that such authority was vested in the FTC, “even if it fell beyond the scope of the Sherman Act.”20

The FTC estimated that one in five American workers is bound by a noncompete clause, with evidence suggesting their use increasing over time.21 The primary study relied upon by the FTC showed that only 10.1% of workers subject to a noncompete clause reported bargaining over the clause, and only 11.4% of workers thought that they still would have been hired had they refused to sign the noncompete clause.22 The use of noncompetes, according to the FTC, operated to reduce wages across the labor market, even for those workers not covered by a noncompete clause.23 The FTC also cited studies showing that noncompete clauses contribute to wage gaps among women and nonwhite workers.24 The FTC further found that noncompete clauses negatively affect competitive conditions in both labor markets and in markets for products and services25 and that they are exploitative and coercive both at the time of

contracting and at the potential end of the employment relationship.26

On April 23, 2024, the FTC adopted the final version of the rule. The rule, to be codified at 16 C.F.R. Part 910, declares that it is an unfair method of competition for a person “(i) To enter into or attempt to enter into a non-compete clause; (ii) To enforce or attempt to enforce a non-compete clause; or (iii) To represent that the worker is subject to a non-compete clause.”27 Under the rule, a noncompete clause is defined as “[a] term or condition of employment that prohibits a worker from, penalizes a worker for, or functions to prevent a worker from: (i) Seeking or accepting work in the United States with a different person where such work would begin after the conclusion of the employment that includes the term or condition; or (ii) Operating a business in the United States after the conclusion of the employment that includes the term or condition.”28 The FTC’s definition of worker includes both employees and independent contractors.29 The new rule also requires employers who have entered into noncompete agreements with workers to a noncompete clause to give them notice that those clauses are now unenforceable.30 If the rule is allowed to go into effect, then it will be effective as of September 4, 2024. While the law will retroactively void most noncompete clauses, it will not affect any causes of action that accrued before the effective date.31

The FTC substantially adopted the proposed rule with a few changes. Dropped from the final rule were codified examples of what the FTC referred to as “de facto non-compete clauses.”32 Those examples included a nondisclosure agreement “written so broadly that it effectively precludes the worker from working in the same field after the conclusion of the worker’s employment with the employer” and a provision that would have required an employee to repay

training costs “if the worker’s employment terminates within a specified time period, where the required payment is not reasonably related to the costs the employer incurred for training the worker.”33 Still, a contract provision may still fall within the scope of the final rule if it has the effect of prohibiting someone from working within a similar industry at the conclusion of their current employment.

In addition, while both the proposed rule and final rule did not apply to noncompete clauses ancillary to the sale of a business, the proposed rule stated that the rule would not apply to a “substantial owner, substantial member, and substantial partner” (defined as an owner, member, or partner owning at least a 25 percent interest in a business) of a business entity when that owner, member, or partner was selling all or substantially all of the business entity’s assets.34 The adopted rule eliminates this language, opting instead to exclude from the scope of the rule noncompete agreements that are ancillary to a “bona fide sale of a business entity” or its assets.35

Finally, the proposed rule would have rendered void all noncompete clauses. When proposing the rule, the FTC stated that noncompete clauses still negatively affected the market when applied to senior executives, but it declined to “preliminarily find non-compete clauses for senior executives are exploitative and coercive at the time of contracting or at the time of the worker’s potential departure.”36 Accordingly, it sought comments to determine whether senior executives ought to be held to different standards. The final rule makes a distinction between ordinary workers and “senior executives,” defined as a worker in a policymaking position and receiving annual compensation of at least $151,164.37 Senior executives are governed by the new rule, except that noncompete clauses signed by senior executives before the effective date of the rule may still be enforced.38

While the FTC is exercising broad authority, the FTC’s authority does not extend to all workers. The FTC Act specifically excludes banks, savings and loan institutions, credit unions, certain common carriers, and businesses subject to the Packers and Stockyards Act from the exercise of its authority.39 In such cases,

however, other regulations may come into play dictating the employment relationship. The FTC also acknowledged that the Rule does not cover nonprofits, as the FTC only has the authority to regulate for-profit businesses.40

Going Forward

There is a question, however, as to whether the rule will ultimately go into effect. Within a day of the FTC’s announcement of the final rule, two lawsuits were filed challenging the FTC’s authority to adopt the rule: one by Ryan, LLC in the Northern District of Texas,41 and one by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, filed in the Eastern District of Texas.42 Ryan makes three broad arguments: that the FTC lacks statutory authority to regulate noncompete clauses; that in the event that the FTC does have the authority to so regulate, it constitutes an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power; and that the FTC is unconstitutionally exercising executive power.43 The U.S. Chamber of Commerce makes these same arguments,44 but it also adds the arguments that a finding that all noncompete clauses are “unfair methods of competition” is contrary to the FTC’s authority under Section 5 of the FTC Act; that the FTC lacks the authority to issue retroactive regulations; that the FTC failed to engage in reasoned decisionmaking; and that the FTC failed to consider alternative proposals.45 While this article does not offer an opinion on the issues raised in these lawsuits, it acknowledges the potential for litigation to delay enforcement of the rule.

But even if the FTC’s rule never goes into effect, the FTC has reinvigorated the discussion of the extent to which noncompetes should be allowed in employment agreements. North Dakota and Oklahoma have longstanding laws that have barred noncompete clauses in employment agreements.46 In 2023, Minnesota passed a bill prospectively banning noncompete clauses in employment agreements.47 California, which already had strong laws prohibiting noncompete clauses, also passed a broad bill banning noncompete clauses and making them unenforceable under California law, “regardless of whether and when the contract was signed.”48 Over the years, other states have put in

other restrictions on the enforceability of noncompete clauses.49 For example, several states plus the District of Columbia have statutes that prohibit enforcement of noncompete clauses against low-wage workers.50

The discussion regarding enforceability of noncompetes is happening in Arkansas as well. In 2023, a bill was introduced that would have repealed Arkansas’s noncompete statute and rendered noncompete clauses unenforceable.51 The bill ultimately died in committee at sine die adjournment, but with the issue on the minds of many, the bill could be reintroduced in some form in the 2025 session.

For now, attorneys should advise affected employers to start preparing “clear and conspicuous” notice to all workers whose agreements are unenforceable by the effective date. The final rule has provided model language for this notice. Employers should also analyze whether certain workers will qualify as “senior executives” who will remain bound by their preexisting noncompete agreements.

Attorneys should also help employers examine whether other forms of restrictive covenants, such as nonsolicitation clauses and training repayment agreement provisions, will have the same effect as a noncompete clause. Though the FTC removed from the final rule language banning de facto noncompetes, it cautioned that a nondisclosure clause can operate as a noncompete clause when it spans “such a large scope of information that they function to prevent workers from seeking or accepting other work or starting a business.”52 Likewise, a nonsolicitation agreement can meet the definition of a noncompete if it prevents a worker from accepting other work or starting a business.

Attorneys can also help their employer clients explore other ways to protect their interests. For example, the “inevitable disclosure” doctrine may allow employers to still seek injunctions in order to protect trade secrets. In Cardinal Freight Carrier, Inc. v. J.B. Hunt Transportation Services, Inc., 53 the Arkansas Supreme Court held that a plaintiff may prove a claim of tradesecret misappropriation by demonstrating a defendant’s new employment will inevitably lead him to rely on plaintiff’s trade secrets.

In that case, the trial court found that the employee continued to work with the former employer’s clients, the new employer would compare itself to the future plans and operational capacity of the former employer, and the new employer expressed an intention to profit based on the disclosure of trade secrets. The Arkansas Supreme Court held that this was sufficient evidence to show inevitable misappropriation of trade secrets; therefore, an injunction was proper.

Arkansas employers may be able to argue a similar theory when employees have signed confidentiality agreements when the disclosure of the trade secrets appears to be inevitable. The analysis of this doctrine is extremely fact-intensive, so any employer should confer with their legal counsel prior to seeking an injunction to enforce a confidentiality agreement.

Conclusion

The FTC’s new rule, if it goes into effect, will make it harder for employers to restrict their employees from working for a competing business at the end of the employment relationship. But even if the rule ultimately does not go into effect, now is a good time for attorneys to help employers review their agreements with employees and, if necessary, help them find other ways to protect their legitimate business interests.

Endnotes:

1. Restatement (Second) of Contracts

§ 186(1).

2. Id. § 187.

3. Id. § 188(2).

4. Id. § 188(1)(a).

5. Id. § 188(1)(b).

6. 2015 Ark. Acts 921 (codified at § 4-75101).

7. Compare Ark. Code Ann. § 4-75-101 with, e.g., Optical Partners, Inc. v. Dang, 2011 Ark. 156, 381 S.W.3d 46; HRR Ark., Inc. v. River City Contractors, Inc., 350 Ark. 420, 87 S.W.3d 232 (2002); Bendinger v. Marshalltown Trowell Co., 338 Ark. 410, 994 S.W.2d 468 (1999); McLeod v. Meyer, 237 Ark. 173, 372 S.W.2d 220 (1963).

8. Anthony L. McMullen, Arkansas’ New Covenant Not to Compete Statute: More Than a Codification of Common Law, 501 Ark. Law. 28, 29 (Fall 2015).

9. Ark. Code Ann. § 4-75-101(f).

10. Id. (citing John M. Norwood, Non Compete Agreements: Can They Be Enforced?, 2009 Ark. L. Notes, 141, 145).

11. See Hyde v. C M Vending Co., Inc., 288 Ark. 218, 703 S.W.2d 862 (1986) (citing appropriate cases).

12. See generally Ferdinand S. Tinio, Annotation, Sufficiency of consideration for employee’s covenant not to compete, entered into after inception of employment, 51 A.L.R.3d 825, at § 3 (1973).

13. See Ark. Code Ann. § 4-75-101(g); see also Tinio, supra note 12.

14. 2020 Ark. App. 62, 595 S.W.3d 378.

15. Id. at 16, 595 S.W.3d at 388 (quoting Duffner v. Alberty, 19 Ark. App. 137, 139, 718 S.W.2d 111, 112 (1986)).

16. Id. at 17–18, 595 S.W.3d at 389.

17. See FTC Proposes Rule to Ban Noncompete Clauses, Which Hurt Workers and Harm Competition, Federal Trade Commission (2023), available at https://www.ftc.gov/ news-events/news/press-releases/2023/01/ ftc-proposes-rule-ban-noncompete-clauseswhich-hurt-workers-harm-competition (last accessed May 18, 2024).

18. See id.

19. Statement of Chair Lina M. Khan on the Adoption of the Statement of Enforcement Policy Regarding Unfair Methods of Competition Under Section 5 of the FTC Act (Nov. 10, 2022), available at https://www.ftc. gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/ (last accessed May 18, 2024).

20. Id.

21. FTC Non-Compete Clause Rule, 88 Fed. Reg. 3482, 3485 (proposed Jan. 19, 2023) (to be codified at 16 C.F.R. pt. 910) (citing Evan P. Starr, James J. Prescott, & Norman D. Bishara, Noncompete Agreements in the U.S. Labor Force, 64 J.L. & Econ. 53, 53 (2021)).

22. Id. at 3486 (citing Starr et al., supra note 21).

23. See id. at 3486–87.

24. Id. at 3488 (citing Matthew S. Johnson, Kurt Lavetti, & Michael Lipsitz, The Labor Market Effects of Legal Restrictions on Worker Mobility 2 (2020), https://papers.ssrn.com/ sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3455381).

25. FTC Non-Compete Clause Rule, 88 Fed. Reg. at 3500–02.

26. Id. at 3502–04.

27. FTC Non-Compete Clause Rule [Final], 89 Fed. Reg. at 38502–03 (to be codified at 16 C.F.R. § 910.2(a)).

28. Id. at 38502 (to be codified at 16 C.F.R. § 910.1).

29. Id.

30. Id. at 38503 (to be codified at 16 C.F.R. § 910.2(b)(1)).

31. See id. (to be codified at 16 C.F.R. § 910.3(b)).

32. See FTC Non-Compete Clause Rule, 88 Fed. Reg. at 3535.

33. Id.

34. Id. at 3535–36.

35. FTC Non-Compete Clause Rule, 89 Fed. Reg. 38342, 38504 (May 7, 2024) (to be codified at 16 C.F.R. § 910.3(a)).

36. FTC Non-Compete Clause Rule, 88 Fed. Reg. at 3520.

37. FTC Non-Compete Clause Rule, 89 Fed. Reg. at 38502 (to be codified at 16 C.F.R. § 910.1).

38. Id. at 38503 (to be codified at 16 C.F.R. § 910.2(a)(2)).

39. See 15 U.S.C. § 45(a)(2).

40. FTC Non-Compete Clause Rule, 89 Fed. Reg. at 38357.

41. Complaint, Ryan, LLC v. Federal Trade Commission, No. 3:24-cv-986 (N.D. Tex. Apr. 23, 2024).

42. Complaint, Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America v. Federal Trade Commission, No. 6:24-cv-00148 (E.D. Tex. Apr. 24, 2024).

43. Ryan, at ¶¶ 51–68.

44. See Chamber of Commerce, at ¶¶ 88–92, 98–101

45. Id. at ¶¶ 93–97, 102–120.

46. See N.D. Cent. Code § 9-08-06; Okla. Stat. tit. 15 § 219A.

47. 2023 Minn. Laws 53, codified at Minn. Stat. § 181.988.

48. 2023 Cal. Stat. 157, codified at Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 16600.5.

49. For a 50-state overview of the current status of noncompete agreements, see Economic Innovation Group, State Noncompete Law Tracker, available at https:// eig.org/state-noncompete-map (last accessed May 18, 2024).

50. See id. (citing relevant statutes).

51. See H.R. 1628, 94th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Ark. 2023).

52. FTC Non-Compete Clause Rule, 89 Fed. Reg. at 38364.

53. 336 Ark. 143, 987 S.W.23d 642 (1999). ■

Between a Rock and a Set of Billing Guidelines

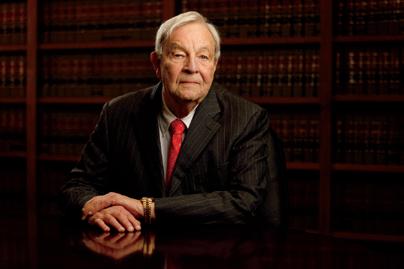

By Gordon S. Rather, Jr.

Gordon S. Rather, Jr., is a partner at Wright Lindsey Jennings. Special thanks to Bregje de Vet, summer associate at Wright Lindsey Jennings, and a J.D. Candidate 2025 at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law.

Those of us who defend cases and are strapped to the rack of billable hours know how excruciatingly detailed time entries must be to comply with clients’ billing guidelines and to pass muster with legal auditors. And as those plaintiff lawyers who do not practice law in six-minute increments know, you may need to provide detailed time records to support a petition for attorney’s fees after successfully handling a case. In either event, these time entries often provide a “window” to your legal strategy, your analysis of the issues involved, and your concerns about the merits of the claims or defenses. Understandably, some of the more sensitive information in these time entries may be privileged or confidential and protected as attorney work product. This article discusses some of the considerations that are involved when an attorney’s billing records must be disclosed to an adversary and to the court.

I. How to Lose $115 Million Because of Billing Records

Disclosing information in billing records can be a minefield for attorneys. Counsel for Zest Labs stumbled on one when they moved for attorney’s fees after being awarded $115 million in a lawsuit against Walmart.1 Zest won the case, presided over by District Judge James M. Moody, Jr., after a jury determined that Walmart had stolen trade secrets.2 Zest had represented that it did not have Walmart Patent Applications before they became public.3 However, its attorney’s time records, which accompanied the petition for attorney’s fees, revealed that Zest had made case-altering misrepresentations4 when those time records showed that Zest knew of the unpublished patent application months before Walmart produced it.5

The court found that Zest’s failure to disclose notice of Walmart’s patent application was “material and not merely cumulative or impeaching,” and that “this evidence would probably produce a different result at trial.”6 As a result, the court granted Walmart’s motion for a new trial.7 The court also found that the motion and brief “do not include privileged material and there is no compelling reason to override the public’s right to access the documents.”8 While the information was not privileged, this case dramatically demonstrates what time records can divulge.

II. How Billing Guidelines Come Into Play

Although plaintiff lawyers do not have to face the scrutiny of legal auditors, they should be aware of the high demands on defense lawyers relating to billing records. Most billing guidelines require appropriate descriptions of legal services using tenths of an hour (0.10). While billing attorneys are instructed not to violate attorney-client privilege, time entries must specifically describe the parties involved and the subject matter of all communications. It is not uncommon for prior approval to be necessary which often requires a detailed explanation of the nature and expected benefit of the work involved. When depositions are recommended, evidence to be developed must be considered. When experts are engaged, their opinions on liability and damages are key issues. It is obvious that the time entries concerning all of these activities are likely to include privileged information or attorney work product, especially when legal auditing services are involved in approving or disallowing every time entry included in a law firm’s invoice.

III. How Issues of Privilege Arise

As a result of the requirement for detailed billing records, lawyers must be keenly aware of the tension between divulging sufficient information to get paid and issues of attorney-client privilege. We all know attorneys are required to keep certain aspects of their representation confidential and cannot be forced to reveal that information. A majority of courts, including the Eighth Circuit, have found that although “attorney-client privilege protects confidential disclosures made by a client to an attorney in order to obtain legal representation, . . . it ordinarily does not apply to client identity and fee information.”9 The Ninth Circuit clearly explained the strong policy reasons for why fee arrangements should not be privileged.10 It held that because courts have the inherent power to regulate the bar, courts have the right to inquire into fee arrangements.11 This allows courts to protect clients from excessive fees, assist attorneys in fee collection, and protect against suspected conflicts of interest.12

District Judge Billy Roy Wilson has expressed his exasperation with lawyers requesting unreasonably large amounts for attorney’s fees in connection with approval of a settlement in a Fair Labor Standards Act collective-action.13 Judge Wilson found that the lawyers’ fees of almost $50,000 were inflated through excessive billing, undocumented costs, and increased hourly rates.14 Judge Wilson stated that “[i]f it

were not for the mandatory language of the statute, . . . I would deny Plaintiffs’ lawyers any fees, out-of-hand.”15 This case underscores the power of the courts to examine fee arrangements, and why they are not privileged.

Many courts recognize, however, that some details contained in billing information may still be privileged. The Eighth Circuit calls this the “confidential communications exception.”16 This exception protects client identity and fee information if revealing that information would require the attorney to disclose confidential communications.17 The First Circuit found that billing statements were privileged if they disclosed the attorney’s advice or details about the investigation of the client’s claim.18 The Third Circuit stated “[i]t is generally accepted . . . that attorney billing statements and time records are protected by the attorney-client privilege only to the extent that they reveal litigation strategy and/or the nature of the services performed.”19 The Ninth Circuit also decided that “bills, ledgers, statements, and time records which also reveal the motive of the client in seeking representation, litigation strategy, or the specific nature of the services provided, such as researching particular areas of law, fall within the [attorney-client] privilege.”20 Consistent with this, attorneys must be careful about disclosing billing records with privileged information to third parties. The Eighth Circuit has held that “voluntary disclosure

“Parties should be rewarded when they successfully engage in litigation where attorney’s fees can be recovered. On the other hand, counsel for the party seeking to recover attorney’s fees must be intentional with regard to what information is disclosed through billing records. When faced with producing these billing statements, it is essential to be extremely careful and to recognize the dangers involved.”

is inconsistent with the confidential attorney-client relationship and waives the privilege.”21

IV.

How Courts in Arkansas Have Responded

Unsurprisingly, issues involving the privileged information contained in billing statements generally arise in cases where the court must assess and award attorney’s fees. As the Ninth Circuit noted, courts have a vested interest in accurately assessing fees as they must protect both clients and attorneys alike.22 The court’s need for accurate and sufficient billing information is frequently at odds with the attorney’s need to keep communications confidential in these situations.

In an effort to preserve the privilege, attorneys often redact billing statements and time records. This can result in situations where courts end up denying or reducing requested fee amounts because they cannot accurately determine reasonableness based on the redacted billing information. A number of Arkansas cases demonstrate this phenomenon. In Bonds v. Langston Companies, the Eastern District of Arkansas stated that “while the Court appreciates the importance of maintaining confidentiality, [party’s] redactions make it impossible for the Court to determine the reasonableness of the entries.”23

Some attorneys have simply refused to provide their billing statements. The Arkansas Supreme Court affirmed a circuit

court’s denial of attorney’s fees on crossappeal where defendants-appellees had not provided copies of the itemized billing statements to the plaintiffs-appellants.24

The defendants-appellees argued that the invoices contained privileged information.25 Although the defendants-appellees had provided copies of the billing statements to the court for in camera review, our Supreme Court noted they did not explain why they did not redact the statements and furnish redacted invoices to the opposing parties.26 As a result, no fees were recovered.27

The difficult position that attorneys are put in when balancing the need to preserve privilege and still provide the court with sufficient information is clear. Unfortunately, the solution to the problem is somewhat unclear.

V. How to Protect Privilege While Providing Adequate Information to the Court

No official ruling or other guidance gives attorneys the answer concerning how to proceed in these types of situations. Studying various opinions, however, suggests a solution that some courts have been willing to accept.

District Judge Lee P. Rudofsky presided over a series of cases in 2023 where attorney’s fees were at issue.28 In each of these cases, the billing statements were redacted, and Judge Rudofsky reduced some fee amounts because the time entries were too vague for the court to assess the reasonableness.29 But in the footnotes for each of these cases, Judge Rudofsky stated that the party could ask the court to reconsider its decision regarding attorney’s fees and file time entries related to client communications under seal.30 In Bonds v. Langston, the parties did file a motion for limited reconsideration ex parte with the unredacted and sealed client communications attached.31 This allowed the court to more accurately evaluate the claims and resulted in an additional award of over $3,000 in attorney’s fees.32

The Arkansas Supreme Court’s decision in Van Carr Enters., Inc. v. Hamco, Inc. suggests that only providing copies of the billing statements for an in camera review, without providing redacted statements to the other party, is insufficient.33 To be on

the safe side, providing redacted invoices accessible to the opposing party, while also submitting unredacted versions for in camera review by the court, may be the best way to ensure that your petition for attorney’s fees will be fully considered.

Conclusion

Parties should be rewarded when they successfully engage in litigation where attorney’s fees can be recovered. On the other hand, counsel for the party seeking to recover attorney’s fees must be intentional with regard to what information is disclosed through billing records. When faced with producing these billing statements, it is essential to be extremely careful and to recognize the dangers involved.

Endotes:

1. Serenah McKay, Re-trial Date Set in Walmart Trade Secrets Suit, Ark. Democrat Gazette (Mar. 4, 2024), https://www. arkansasonline.com/news/2024/mar/04/retrial-date-set-in-walmart-trade-secrets-suit/.

2. Blake Brittain, Walmart Hit with $115 Million Verdict over Food-waste Trade Secrets, Reuters (Apr. 12, 2021), https://www. reuters.com/article/idUSL1N2M5326/.

3. Defendant’s Brief in Support of Motion to Dismiss, or Alternatively, for New Trial and Accompanying Sanctions, and for Attorney’s Fees 1, Zest Labs Inc. v. Walmart Inc., 4:18CV00500JM (Sept. 26, 2023) ECF No. 508.

4. Id.

5. Id. at 1–2.

6. Order 2, Zest Labs Inc. v. Walmart Inc., 4:18CV00500JM (Dec. 22, 2023) ECF No. 530.

7. Id.

8. Id.

9. United States v. Sindel, 53 F.3d 874, 876 (8th Cir. 1995).

10. In re Michaelson, 511 F.2d 882, 888–889 (9th Cir. 1975).

11. Id.

12. Id.

13. Vines v. Welspun Pipes, Inc., 453 F. Supp. 3d 1156, 1157, 1161 n.29 (E.D. Ark. 2020), aff'd, 9 F.4th 849 (8th Cir. 2021).

14. Id. at 1158 n.10.

15. Id. at 1161.

16. Sindel, 53 F.3d at 876.

17. Id.

18. In re San Juan Dupont Plaza Hotel Fire Litigation, 111 F.3d 220, 232 (1st Cir. 1997).

19. Leach v. Quality Health Services, 162 F.R.D. 499, 501, 33 Fed. R. Serv. 3d 61 (E.D. Pa. 1995).

20. Clarke v. Am. Com. Nat’l Bank, 974 F.2d 127, 129 (9th Cir. 1992).

21. In re Grand Jury Proc. Subpoena to Testify to: Wine, 841 F.2d 230, 234 (8th Cir. 1988).

22. See In re Michaelson, 511 F.2d at 888–889.

23. Bonds v. Langston Companies, Inc., No. 3:18-CV-00189-LPR, 2021 WL 4130508, at *5 (E.D. Ark. Sept. 9, 2021).

24. Van Carr Enters., Inc. v. Hamco, Inc., 365 Ark. 625, 633–34, 232 S.W.3d 427, 433 (2006).

25. Id.

26. Id.

27. Id. at 634.

28. See generally Mitchell v. Brown's Moving & Storage, Inc., No. 4:19-CV-783-LPR, 2023 WL 2715027 (E.D. Ark. Mar. 29, 2023); Brown v. Trinity Prop. Mgmt., LLC, No. 4:19-CV-617-LPR, 2023 WL 2715022 (E.D. Ark. Mar. 29, 2023); Huey v. Trinity Prop. Mgmt., LLC, No. 4:20-CV-685-LPR, 2023 WL 2715271 (E.D. Ark. Mar. 29, 2023).

29. Mitchell, 2023 WL 2715027, at *7; Brown, 2023 WL 2715022, at *5; Huey, 2023 WL 2715271, at *7.

30. Mitchell, 2023 WL 2715027, at *7 n.78; Brown, 2023 WL 2715022, at *5 n.60; Huey, 2023 WL 2715271, at *7 n.75.

31. Bonds v. Langston Companies, Inc., No. 3:18-CV-00189-LPR, 2021 WL 5814277, at *1 (E.D. Ark. Dec. 7, 2021).

32. Id. at *2.

33. Van Carr Enters., Inc., 365 Ark. at 633–34. ■

Choice of Law and the Attorney-Client Privilege: Thinking Before You Speak

By William A. Waddell, Jr.

The attorney-client privilege is the oldest of the privileges known to the common law.1 Before Arkansas adopted rules of evidence that defined the privilege, Arkansas case law characterized it as a matter of public policy:

Such is the rule, wisely laid down by the law, …. It was adopted from reasons of public policy, and through a regard to the interests of justice. A wise policy encourages and sustains the most unlimited and generous confidence between lawyer and client by requiring that on all facts confided in professional consultation the lips of the attorney shall be forever sealed.2

Our understanding of the privilege has moved a long way from the policy that “the lips of the attorney” are “forever sealed.” This article explores how our basic understanding of the privilege may be subject to further consideration in this day and age of multi-jurisdictional practice.

William A. Waddell, Jr., is a partner at Friday, Eldredge & Clark LLP in Little Rock. He is a member of the firm's litigation practice group.

The privilege, as succinctly stated in Rule 502 of the Arkansas Rules of Evidence, has been refined to a focused rule of evidence and is not as broadly stated or understood as earlier case law decided under the common law:

(b) General Rule of Privilege. A client has a privilege to refuse to disclose and to prevent any other person from disclosing confidential communications made for the purpose of facilitating the rendition of professional legal services to the client (1) between himself or his representative and his lawyer or his lawyer’s representative, (2) between his lawyer and the lawyer’s representative, (3) by him or his representative or his lawyer or a representative of the lawyer to a lawyer or a representative of a lawyer representing another party in a pending action and concerning a matter of common interest therein, (4) between representatives of the client or between the client and a representative of the client, or (5) among lawyers and their representatives representing the same client.

While many states have adopted the Uniform Rules of Evidence as Arkansas has,3 the case law interpreting those rules in each state, including the rule regarding the attorney-client privilege, cannot be said to be uniform across jurisdictions and often depends upon the relationship of the rule to other state-specific rules or case law.4 For example, in Schipp v. Gen. Motors Corp.,5 the court noted the jurisdictions in which statements between an insured and insurer are not privileged, and then concluded that Arkansas law would hold that investigation reports containing such statements are privileged.6

Waiver of the privilege is also the subject of a succinct rule:

Rule 510. Waiver of Privilege by Voluntary Disclosure.

A person upon whom these rules confer a privilege against disclosure waives the privilege if he or his predecessor while holder of the privilege voluntarily discloses or consents to disclosure of any significant part of the privileged matter. This rule does not apply if the disclosure itself is privileged.

However, that rule continues to be the subject of case law that illuminates nuances of the rule on waiver. For example, failure to object to discovery requests on the basis of privilege can cause a broad subject-matter waiver of the privilege.7 And like the variations in interpreting the concept of privilege itself, the statespecific nuances of the waiver rule are likely not uniform. Perhaps most importantly in the context of this article, it should be noted that the foregoing rules and related case law are matters of evidence. Waiting to determine whether a communication is protected by the privilege until there is an evidentiary question in a legal proceeding is not advised. While case law abounds as to the nuances of the attorney-client privilege, there has been little discussion in Arkansas of whether the law of other jurisdictions may be applicable to a communication made by an Arkansas lawyer that is intended to be privileged.

Choice of Law and The Attorney-Client Privilege

If a privileged communication is made by an attorney in Arkansas and the question is whether Ark. R. Evid. 502 and 510 apply in a court proceeding in Arkansas, analogous cases involving other privileges suggest that both federal and state courts in Arkansas would hold that the law of the forum (i.e., Arkansas) applies.8

The applicable law is not so clear, however, when a lawyer (either licensed in Arkansas or some other jurisdiction) makes a communication that is thought to be privileged under the law where the communication is made or when a communication thought to be privileged in Arkansas is evaluated under the law applicable to a forum outside this state. Multi-jurisdictional transactions (some with choice-of-law and stipulations as to the

forum for disputes) and resulting litigation present questions that have apparently not yet been addressed by Arkansas courts in reported decisions. However, these types of questions have been the focus of articles that reflect the trans-state and even trans-national nature of modern commerce.9

Until Arkansas courts give more guidance concerning how to address privilege issues (both as to whether the communication is privileged and whether the privilege has been waived) based on choice-of-law principles, lawyers should consider how § 139 of the Restatement (Second) of Conflicts of Laws (1971 & March 2024 Update) may inform such issues. Section 139 provides as follows:

(1) Evidence that is not privileged under the local law of the state which has the most significant relationship with the communication will be admitted, even though it would be privileged under the local law of the forum, unless the admission of such evidence would be contrary to the strong public policy of the forum.

(2) Evidence that is privileged under the local law of the state that has the most significant relationship with the communication but which is not privileged under the local law of the forum will be admitted unless there is some special reason why the forum policy favoring admission should not be given effect.

Comment d to § 139 provides detailed guidelines for applying these rules that are “among the factors that the forum will consider in determining whether or not to admit the evidence,” including “whether the privilege belongs to a person who is not a party to the action.” In that circumstance, the Restatement authors opine that “the forum will be more inclined to recognize the privilege and to exclude the evidence than it would be in a situation where the privilege is claimed by a person who is a party to the action.”

Comment e discusses § 139’s core concept of the state of “most significant relationship”:

The state which has the most significant relationship with a communication will usually be the state where the communication took place, which, as used in the

rule of this Section, is the state where the oral interchange between persons occurred, where a written statement was received or where an inspection was made of a person or thing. The communication may take place in a state different from that whose local law governs the rights and liabilities of the parties. So in a case involving an issue in contract that is governed by the local law of state X under the rule of § 187, a question of privilege may arise that took place in state Y.

It is obvious that the drafters of § 139 have given choice-of-law issues regarding the attorney-client privilege a lot of thought, and the Restatement’s treatment of those issues warrants consideration by practicing attorneys before communications are made in the different contexts covered.

Thus, when an Arkansas lawyer negotiates an agreement that provides for the law of Delaware to govern and stipulates to Delaware as the forum for disputes and then communicates with her Arkansas-based client corporation, Arkansas privilege law would seem to apply to those communications to the extent they meet the requirements of Ark. R. Evid. 502. And issues of waiver of her privileged communications would be governed by Ark. R. Evid. 510 and related case law interpreting that rule. Under § 139 of the Restatement (Second) of Conflicts of Laws, it would therefore appear that Arkansas has the most significant relationship with the privileged communications made in that situation. However, if subsection 2 of § 139 is applied, and if the privilege issue is challenged in a Delaware forum and Delaware law either does not consider the communication privileged or would find the privilege has been waived, then the communication would be subject to disclosure and “admitted unless there is some special reason why the forum policy favoring admission should not be given effect.” An Arkansas lawyer making such a communication in a transaction that will be governed by Delaware law and will be litigated in Delaware if there is a dispute involving the agreement should

at least be cognizant of the potential that her client communications will be subject to disclosure. That awareness may change both the nature, content, and frequency of communications. Presentday electronic discovery techniques may result in the transactional lawyer’s e-mail communications with the client being captured in a document search of the client’s database that is reviewed by another lawyer with less concern for, or scrutiny of, the transactional lawyer’s communications. That lawyer may also view privilege issues with the perspective of another state’s rules on the subject.

A transaction may also involve lawyers from multiple jurisdictions representing the same client who is domiciled in a separate jurisdiction. This situation would complicate determining which state’s law applies to the privilege issues, but again these are matters that merit at least some consideration before substantive privileged communications commence.

Another unanswered question based on the current state of Arkansas law is what privilege law applies when the forum is an arbitration or regulatory body and not a court that has rules of evidence. If a transaction calls for the parties to resolve any disputes by arbitration, the parties will likely have stipulated the governing law for the transaction. Accordingly, the provisions of § 139 could be applied in the arbitration to decide matters of privilege. However, as with the other contexts discussed above, care should be taken to consider privilege issues before applicable law or forum selection are stipulated in a transaction.

Aside from transactional matters and privilege, communications intended to be privileged that are related to litigation may also involve the same issues as to which law applies. In actual litigation involving multi-jurisdictional issues, attorneys can either stipulate with other counsel as to matters of privilege, including what law applies, or if necessary, they can obtain a ruling from the court, arbitrator or hearing officer as to how matters of privilege will be evaluated in the course of discovery or the presentation of evidence at a hearing or trial. However, pre-litigation matters, such as the investigation of claims, may have to be undertaken before a forum is determined

and choice-of-law considerations have ripened. If the client or material witnesses for the attorney’s client are located in places other than the likely forum where the litigation will take place, then care should be taken to anticipate how the law of the place where the communication takes place would determine privilege issues.

Depositions present a unique but frequent circumstance involving the privilege and the practice of law. Like all lawyers, Arkansas lawyers routinely take depositions of persons outside of Arkansas for cases pending in Arkansas. Matters of attorney-client privilege can easily arise leading to the need for court intervention, both during the deposition and following when a party seeks to use the deposition in a proceeding.10 Comment f to § 139 addresses this issue generally: