15 minute read

Art and Design in Japanese Sword Fittings Part 2

ART AND DESIGN IN JAPANESE SWORD FITTINGS

Part 2 Th e history of Japanese sword making extends for well over a thousand years. Th ey have always been highly prized in Japan, and a surprising number of the swords produced over that millennium exist today in collections in many countries.

Advertisement

By W T L Taylor

menuki

tsuba

kurigata

kashira fuchi kogai (kozuka on opposite side)

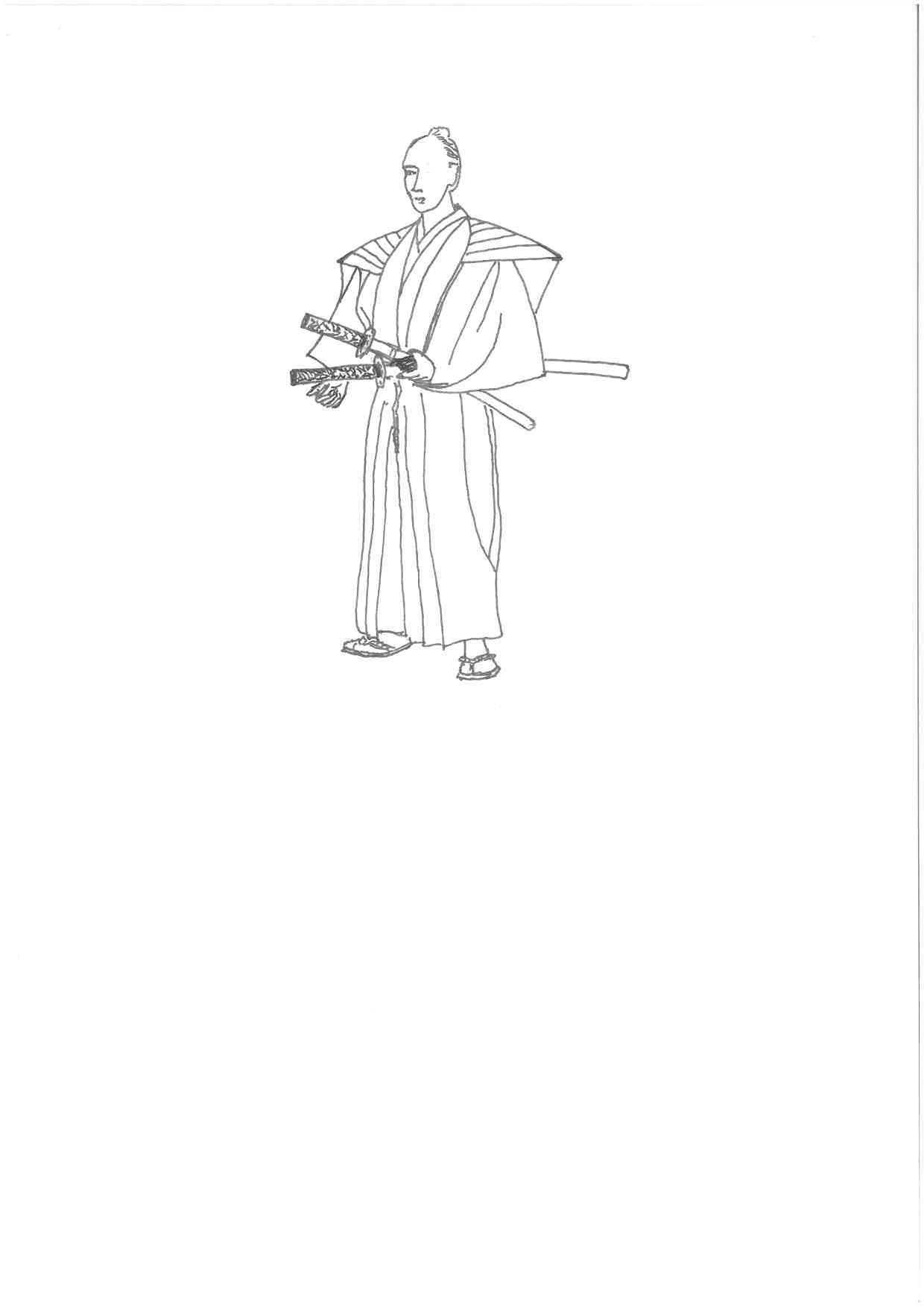

The first of these articles examined the significance of Japanese art in tsubas (hand guards). This second article off ers a brief survey of the miniature art to be found in other main fittings on a typical antique Japanese sword.

As with tsubas, the smaller sword fittings are also canvases for Japanese art and design. They should complement each other on a sword, but other than the matched pair that makes up the hilt end cap and the base collar, do not have to be made by the same craftsman. What is more important is that all the fittings on any sword work together in accordance with Japanese taste.

Fuchi and kashira

The hilt of a sword has an oval cap (kashira) on the end and a collar (fuchi) at the tsuba end. Both pieces are made by the same craftsman as a matching set.

The design on a fuchi and and its kashira is oriented so it is properly appreciated when the sword is being worn. For fuchi, the main design is always located on the side facing out from the wearer.

kojiri

This eighteenth century signed set is in shakudo (deep black patinated alloy of gold and copper), with high relief inlaid silver cherry blossoms with gold leaves and a finely detailed pheasant in gold, silver, copper and shakudo. Cherry blossoms and pheasants are a common theme in Japanese art.

In striking contrast, this signed set is made of shibuichi (a silver grey alloy of silver and copper). The maker used deep engraving to depict bamboo with a narrow crescent of waning moon behind it, inlaid in gold.

Nature is a popular theme in Japanese sword fittings. These spiny lobsters are in very high relief and fine detail: they were admired by samurai because they are hardy and aggressive. The shakudo base is finished in nanako – tiny, hand punched domes.

The moon is a theme that occurs often in Japanese art. This signed set is a scene from the fairy story the Taketori Monogatari, about a humble bamboo cutter who one night found a baby girl in the moonlight and took her home. He and his wife named her Kaguyahime, and she grew to be so famous for her ethereal beauty that she attracted noble samurai, for whom she set impossible quests. The story goes that she ultimately rejected all of them and left to live with her people on the moon.

Her discovery by the bamboo cutter is alluded to on the fittings: the kashira shows his discarded round hat, with a digging tool. The fuchi shows on the front side the startled bamboo cutter tying up a bundle of bamboo cuttings.

The back of the fuchi shows the moon, partially obscured by clouds. There is no sign of the baby – this very oblique way of referencing a well-known legend

is typically Japanese.

The sophistication of Japanese design is evident in this shakudo and gold inlaid set. Gold leaves of the rice plant are finely inlaid into lustrous black shakudo, with the rice set proud of the polished surface. As samurai landowners counted their wealth in the number of bags of rice they produced each year, rice in this example refers to wealth.

Fuchi and kashira

This is a small fuchi kashira set made for mounting on a tanto. It has an egret and fish trap design, unsigned, in shakudo with fine nanako with gold and silver highlights.

This set depicts Daruma (Bodhidharma, the founder of the Zen sect of Buddhism) with his traditional glaring face. He is usually depicted with wide open, staring eyes because according to legend, he once became so angry with himself for falling asleep during meditation that he had his eyelids removed. The fuchi has a bowl (in which people would place food) and a flywhisk to keep the flies away from his eyes.

Bodhidharma was a mysterious figure who lived during the 5th or 6th century. He is traditionally credited with being the transmitter of Chan Buddhism from India to China, and is regarded as its first Chinese patriarch.

Sets made in iron were found on swords set up for hard use in the field. This set is made of iron onto which a delicate gold pattern has been fixed, depicting a pattern of snow crystals and tendrils. Iron fittings are harder to find in good condition because they are more susceptible to rust.

Concluding this brief sample of fuchi/kashira types is a set by a master craftsman from late in the sword wearing period. It is of very fine quality. The set is in shakudo, gold, silver and copper. Its detailed high relief depicts five of the household gods that often appear in Japanese art.

On the kashira is Jurojin with his fan and a long tailed tortoise, and on the front of the fuchi Fukurokuju, Ebisu, and Daikoku with his hammer, with Hotei with his sack on the back. Each of the tiny domes on which the figures are set has been

individually punched by hand.

Orphans

When kashira and fuchi become separated, single pieces (nick-named ‘orphans’ by Western collectors) appear on the market at a fraction of the price their original complete set would be worth, as it is virtually impossible to find the missing piece.

That makes it possible to put together a pleasing collection of orphaned fuchi or kashira like these single pieces. All of the following are of master craftsman quality and can be enjoyed just as

Kashira

miniature artworks.

Fuchi

Menuki

Under the wrapping of a sword hilt is mounted a small pair of fittings called menuki. They are always off set on each side of the hilt in order to assist the swordsman’s grip.

It is typical of Japanese attention to detail that even n though the menuki are largely obscured under the wrapping, they are often as finely made as the other sword fittings.

This set shows two typically cheerful household gods – Ebisu with a large fish, and Daikoku with his hammer. Made in silver and gold, they are very finely finished (their inlaid gold eyes are only 0.5mm).

Another fine quality set in shakudo depicts pairs of gambolling water buff alo. The workmanship is excellent. Note that although obviously a pair, they are not mirror images.

This set in shakudo overlaid with gold shows Japanese nightingales amongst plum blossoms – another favoured theme. They illustrate the rule that almost all pairs of menuki were diff erent to each other. Like the menuki above these appear image reversed at first glance, but are diff erent in detail. The only menuki that were identical were those depicting

family crests (mons).

Kozuka

Antique swords often have a narrow slot on the inwards facing side of the scabbard to house a thin knife blade – called a kogatana - mounted in a rectangular flat handle called a kozuka. Kozuka are collected individually and are fitted with a blade only when they are to be mounted on a sword. The small blades are tempered like their larger cousins and are often inscribed with a signature or a good luck saying.

This 17th century small blade is inscribed with the maker’s name and location. The kozuka is in shakudo with fine nanako and gold highlights, depicting Raijin the thunder god with his drums, and is unsigned. It is mounted on an older sword whose blade is signed and dated 1428.

A shakudo kozuka made by the famous Goto family, which had a monopoly for generations on the supply of formal fittings for swords worn at court, showing a peony flower with a lion dog. It is unsigned but the Goto style is unmistakable.

A signed Goto family piece, alluding to the old story of a wise man (Chokwaro Sennin) who kept a magic horse in miniature in a gourd, which he released when he needed to travel. The horse would grow to full size for the journey, and afterwards would be magically reduced to go back into the gourd. On this kozuka the Chokwaro story is referenced by the horse being shown in miniature relative to the flowers and plants p around it.

Another shakudo based piece from the Goto family, depicting swirling waves with an anchor and glass fishing buoys covered in ropework. The gold and silver work is very detailed.

An iron kozuka with a raised dragon in high relief, finely chiselled, with gold highlights with attractive dark patination. Dragons were greatly favoured in sword design.

A shakudo kozuka of a fan with flying ribbons, all inlaid gold, silver and shibuichi, highly polished.

This lustrous black shakudo kozuka is finely inlaid with gold and silver grape vines, butterflies and a grasshopper.

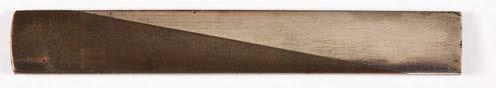

A shibuichi kozuka with finely inlaid gold and silver spirals. Half of its back is a diagonal layer of solid silver: this is a remarkably modern looking design, but dates from the 1800s.

Kogai

Swords may have another slot on the other side of the saya, facing outwards. It is usually for a kogai, a skewer like object which sometimes is split lengthways to form chopsticks.

Edo period kogai of the Goto school unsigned, in shakudo with a single silver and gold camellia design.

Another shakudo with fine relief inlays in gold and silver flowers and grasses on a fine nanako base.

When a kogai is split along its length, it is called a wari-bashi. This design inlaid in fine gold shows cranes flying from a reedbed. There are debates about the use of the wari-bashi: they could have been hairpins for the samurai’s long hair, or chopsticks.

Other Fittings

There are several other fittings found on antique swords, such as the throat of the scabbard, the raised piece (kurigata) on the outer side for fixing a silk holding band, a cap (kojiri) on the bottom of the scabbard and other small pieces. They are most some swords there will be a full matching set made of shakudo, shibuichi, copper or iron. Such swords attract a premium amongst collectors.

Buying a mounted antique sword

As you would expect, the most critical part of a Japanese sword is the blade. Because this article deliberately does not address antique blades (a huge topic), the following comments are directed at examining the mounts only. It is worth noting however that if a blade is pitted with rust, has been chipped, bent, or the tip broken, it is best left – unless the mounts are of such high quality and condition that they are separately valuable.

When experienced collectors examine a mounted sword for sale, after assessing the blade they look for these points in the mounts:

Are any parts loose? Tsubas in particular are prone to be replaced on antique swords, sometimes fitted so poorly that they rattle. You can be assured that no Japanese sword owner would wear a sword on which any mount was not carefully and exactly fitted.

Are all the mounts of similar quality? Finely made fuchi kashira would never be fitted to a sword with a poor quality tsuba.

Do the fuchi kashira match? They should be clearly made by the same artisan with a theme common to both items. If they don’t match, the sword should be avoided. The only exception is when a nice fuchi has been deliberately matched commonly made of polished black horn. However on

with a smooth polished horn kashira on a formal court sword. ● Do the menuki match? They should not be identical, but should have the same theme and be made by the same person. If they look totally diff erent, one is a replacement.

Novice collectors would be wise to ask experienced collectors for advice, and to handle as many swords as possible.

References 1. The Baur Collection, Japanese Sword-Fittings and Associated Metalwork, B.W.

Robinson, 1980 2. Legend in Japanese Art, Henri L. Joly, first published 1908, reprinted subsequently 3. Japanese Art and Handicraft, Henri L. Joly and Kumasaku Tomita, first published 1916, reprinted subsequently 4. The Arts of the Japanese Sword, B. W. Robinson, first published 1961, reprinted subsequently 5. Bonhams London sales catalogues, Fine Japanese Art 6. The Japanese Sword, Kanzan Sato, Kodansha, 1983 7. Lethal Elegance, the art of Japanese sword fittings, Joe Earle, Museum of Fine Arts,

Boston, 2010