4 minute read

The Complicated Legacy of Georgia Gov. Joseph E. Brown From Secession to Reconstruction WANDERER

BY THE WANDERER

Growing up in Missouri, I had to memorize the state motto — Cicero’s famous “Salus Populi Suprema Lex Esto.” Translated: “The good of the people should be the supreme law.” The term populist is used to apply to a politician who strives to appeal to ordinary people who feel their concerns are being ignored by established elitist groups. The presumption therein is politicians in positions of power are corrupt and selfserving, whereas the general public, taken as a whole, is much less so.

Advertisement

In the United States, politics are dominated by a two-party system. Populists find it hard to survive over any extended period of time as they do not receive strong support from the established powers in their own party. Instead, they rely on the support of the common man. Cherokee County’s most famous politician, Joseph Emerson Brown, was such a man, with a successful political career spanning nearly 50 years, to the consternation of most of the politicians of his day.

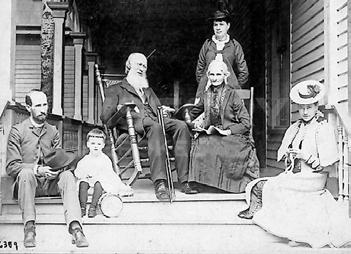

Populists often are self-made, and Brown was no exception. Originally from South Carolina, he moved to Georgia with his parents in 1829, at the age of 8. At 19, he left the family farm and went back to South Carolina for an education, paying his own way and borrowing when he couldn’t. In January 1844, he moved back to Georgia and quickly repaid his debt to the academy by teaching in Canton. Once his debts were paid, he tutored Dr. John Lewis’ children (also in Canton) while studying law in 1844-45. By August 1845, he was admitted to the bar. He briefly attended Yale Law School on a loan from Lewis, but soon left to begin his practice. He joined the Democratic Party, and by 1849, he was in the state Senate representing Cherokee and Cobb counties.

He had little experience, but he was outspoken and emphatic. By the end of the first session, he was becoming the Democratic leader in the Senate. At that time, Georgia politics were under the firm grip of the “Georgia Triumvirate,” composed of Robert Toombs, Alexander Stephens and Howell Cobb, who were serving in Washington, D.C. In 1857, when Brown was nominated as a darkhorse candidate for governor, perhaps the most famous quote about him was uttered. Toombs, upon hearing of the nomination, said, “Who the devil is Joe Brown?” The statement says everything you need to know about just how quickly Brown rose from obscurity to prominence within the party and the state, and without the assistance of any political machinery. Brown would win that election, become governor, and remain so throughout the course of the Civil War, until he resigned in 1865.

Brown believed fervently in the rights of the states to run themselves as their people saw fit. He believed that bringing prosperity to his state was his first responsibility as governor, and would have strongly agreed with fellow Georgian James Carville’s 1992 catchphrase: “It’s the economy, stupid.” As slavery was important to the economy of Georgia, Brown supported it, further charging that if slavery had proved profitable in New England, it would’ve become firmly rooted there also. He was a secessionist, but proved vexing for the Confederacy. Brown believed in secession from federal authority on the basis of states’ rights. Yet, he was equally wary of the Confederate authority in Richmond, Virginia.

Brown’s popularity in Georgia was such that he could raise large numbers of volunteers for the militia in defense of his state. As the Confederacy continued to request (and later demand) his militia for Confederate service, Brown grew concerned he would not be able to defend Georgia from assault. He asked for some of these Georgia-supplied men to be returned; Jefferson Davis diplomatically declined. In response, Brown raised a large additional army of militiamen. When it came time for Davis to ask for them, Brown declined, and far less diplomatically. He had come to view Davis as a “dictator,” and Brown reasoned that without the defense of Georgia’s industry and transportation infrastructure, the South had no hope of success. So, its defense was paramount. The Union Army felt similarly about the critical role of Georgia in support of the Confederate cause, and Gen. William T. Sherman’s March to the Sea was prompted by this belief. History has proven them right, and the war ended shortly thereafter. Ultimately, Stephens of the Georgia Triumvirate would come to respect and support Brown; Toombs and Cobb never would come around. In early May 1865, as the Civil War ended, and at the urging of Cobb, Union Gen. James Wilson forced Brown to sign a surrender and parole agreement. Prior to signing, Brown had called for a special session of the Georgia Legislature to convene on the 22nd of the month. Such an act was in violation of that agreement, and despite the timing and Brown’s lack of awareness about it representing a violation, it would get him arrested and sent to Carroll Prison in Washington. What followed next must have rankled Cobb immensely. Brown managed to arrange for an audience with President Andrew Johnson, saying it would be better to discuss in person the state of affairs in Georgia and the actions he had therefore taken. When they met, President Johnson saw in Brown a fellow “common man of the people.” Johnson himself had risen through the ranks despite the efforts of what he considered the political aristocracy. Brown was quick to admit he had erred in 1861, and he fully accepted the results and outcome of the war. The two parted as friends, and by the end of that month, Johnson pardoned Brown. Brown’s entire incarceration lasted less than a month; he even returned home to his pregnant wife using transportation furnished by the federal government. (Watch for Part 2 in our June issues.)

• www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=21891

The Wanderer has been a resident of Cherokee County for nearly 20 years, and constantly is learning about his community on daily walks, which totaled a little more than 2,000 miles in 2022. Send questions or comments to wanderingga@gmail.com.