2 minute read

Yelena Vorobyeva & Viktor Vorobyev

from Tarjama/Translation: Contemporary art from the Middle East, Central Asia, and its diasporas

by ArteEast

KAZAKHSTAN, 1959

35

Advertisement

We became interested in “socio-coloristic” relations while traveling the south of Kazakhstan in 2002. As participants in the international project “Non-Silk Road,” we visited several provincial towns. In the town of Taraz, our attention was drawn to decorative bas-reliefs with pictures of blue banners on one of the old administrative buildings. These banners used to be red. This blatant repainting of Soviet decorations was striking and provided the best possible illustration of the change in political epochs.

The state symbols that had been canonized by the Communists were now subject to total “de-sacralization.” As the main sign of all things Soviet, the color red was repressed and replaced by other privileged colors all over post-Soviet space.

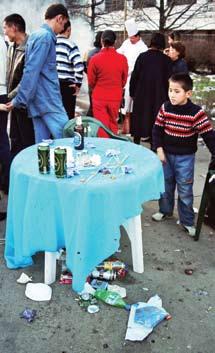

After the republic declared its independence, the Kazakh flag became blue. To be more precise, its color is what you call kok in the Kazakh language—kok means both blue and green. Kok also means “sky,” while koktem means “spring” and kokteu means “becoming green.” Fraught with meaning and symbolizing many things— the “Eternal Blue Sky” in Tengrianism, the nauryz pagan celebration of spring, the blue domes of the Islamic mosques, a dream of the inaccessible ocean’s vast expanse—the color blue was accepted by the majority and entered the mind of the people as the best, most “appropriate” color. The people of Kazakhstan simply love the color blue. How can one otherwise explain all of this repainting, which almost seems like an obsession? Questions of color no longer arise: If something has to be painted, there is already a solution at the ready—the color kok. Kok is Kazakhstan’s best-selling type of paint. Everything is painted with it: fences, kiosks, walls, benches, even the crosses on graves. The sphere of the color’s use is as large as life itself. Objects from the “blue period” are everywhere, in the most varied places and in the strangest combinations. There is a feeling that you are living within a project, and that the Steppe is a huge expositional field that demonstrates a set of artifacts. The cultural strata, which have been accumulated here during the time of their development by man, are specifically perceived in this vein. Materialized in the “blue dream” of “eternal spring,” the color blue has spread throughout the territory of Kazakhstan, adding some optimistic luster to the dim nature of our steppe.

In this way, it could be that society, in yearning for its bygone integrity, is reacting to the instability and the fluidity of the transitional period’s changing situation. The aspirations toward unity are subconsciously realized through identificatory signs— color marks that do not only designate membership in a concrete community but also signify belonging to the “Divine,” to Power.

This is a kind of a charm, “just in case”…

Yelena Vorobyeva