ART

HA B E N S

Holly Marie Armishaw Canada

Repressions embodies a unique approach to the formal qualities of the photographic medium while simultaneously provoking sociopolitical discussion. Each of the photographs in the series depicts a partial view of a woman either releasing various objects, or interacting directly with the frame. The white exhibition frames are no mere formal devices, but active participants in the minor performances of the artworks. The treatment of the frames, and the subject’s engagement with the surfaces of the photographs, connote a consciousness of the invisible confines of the medium. Viewed collectively, one is able to piece together a unifying thematic thread. Three of the works contain pills, which are used to treat pain, anxiety, and depression. Other objects like eggshells and flower petals may suggest a sense of fragility or sensitivity while being intuitively linked to the idea of the feminine, as does the text rendered in nail lacquer. The more “active” works suggest states of struggle, desperation, isolation, and even anger. Evidently, there is more to this series of work than a critique on the 2D tradition of the photographic medium. In a National Population Health Survey conducted between 1994/95 to 2010/11 Statistics Canada reported nearly twice the incidence of childhood abuse in female than male subjects. In 2014 Statistics Canada reported that women constituted approximately 65% of all Canadians with mood disorders. Numerous studies have documented associations between childhood physical abuse and subsequent mental and physical disorders.

Marcelina Wellmer Poland / Germany

The work “Dust” combines generative HD video with the movement of the audience through camera tracking. Since some months I am collecting dust particles on a piece of black plexiglass. Monthly, I photograph the collected set, clean the surface and start from the beginning. The composition and the quantity of dust depend on the movement around the place and other random occurrences. One of the photographed sets I traced in a graphic program, the resulting graphical particles now get animated within the generative video software VVVV. A Kinetic 3D camera tracks the movement in front of the video projection – if somebody gets closer to the projection the dust speeds up and flies into all directions, triggered by the observers motion. The movement of the pixel dust, although looking random, is based on close observations of real dust flying. A complex power field emulates the forces that also appear in real life. The composition is never the same; it happens in real time and by chance – it is a generative chaos. The observers movement is interpreted as an artificial wind source. We humans disturb the dust and let it fly faster. We are a source of wind and motion. Our bodies are now a part of a random, digital artefact, but with roots in real occurrences. The second part of the project are paintings: the photographed dust is painted on canvas and becomes the name of the month – every month one painting. It will be a one year of dust.

Cooke Australia

I am an interdisciplinary scholar and media artist. In one way or another, all my work, as both a scholar and a media artist, is concerned with archives; with personal, collective and environmental archives; with the archive as a touchstone for the re-enchantment of the past; and with the archive as a material thing, the thing by which we can state that history and temporality have a medium. As individuals and societies we accumulate a great deal of “stuff” in archives. The materials that sit in our national archives and museums, for example, are vital to our identity as a people, just as our own individual archives of photographs and memorabilia are important to us personally, they form a kind of material memory. But material memory operates beyond the human as well; the “deep time” of the earth is present in our forest, reefs and mountains, which represent a form of sedimentary and environmental memory that performs a vital de-centering of human concerns. In my work I explore these archives as an opportunity for thinking differently. I am concerned with finding new ways of relating to archives as material forms, ways that might change how we think about ourselves as individuals and nations, and our place in a world that is increasingly subject to our collective technological and economic will.

Sonia GIl Brazil

Sonia GIl Brazil

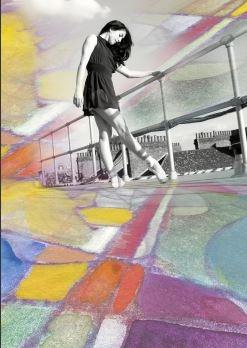

I am an artist and an architect from Rio de Janeiro. My work is focused on cities and on the urban universe, an old passion, that lead me to study Architecture and Urbanism. Along my graduation years, I started to give form to my artistic expression, and gradually, after working as an architect for many years, the art experience became more and more important, so eventually, I landed in the arts for a full time experience. However, the architectural mind is still present, as I try to capture the spirit of the contemporary city, and build, in various layers, images of the transforming urban space. I started with watercolors and moved on to painting, and then moved on to digital. I moved back to watercolor and started to blend in the digitalized paintings with photographs. My lattest works use the re-treatment of images, mixing paintings, photographs and digital, in a process that starts with brush and paint and ends with scanning and digital collage. Working with a diversity of techniques, and mixing different elements is my way of trying to translate the complexity of the contemporary life and the urban environment. Art to me is a process, a very unsettling one.

I am also co-founder of the Urban Dialogues group, an network of artists from different cities, working with the idea of sharing, collaborating, constructing and reconstructing images of the urban landscape, in search of learning and reflecting about our differences and similarities.

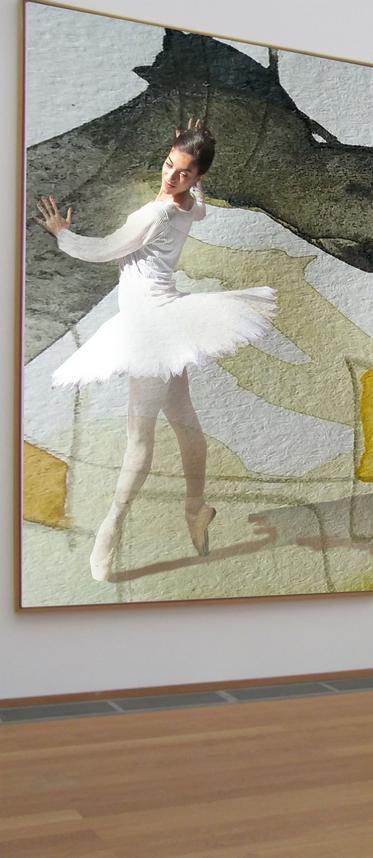

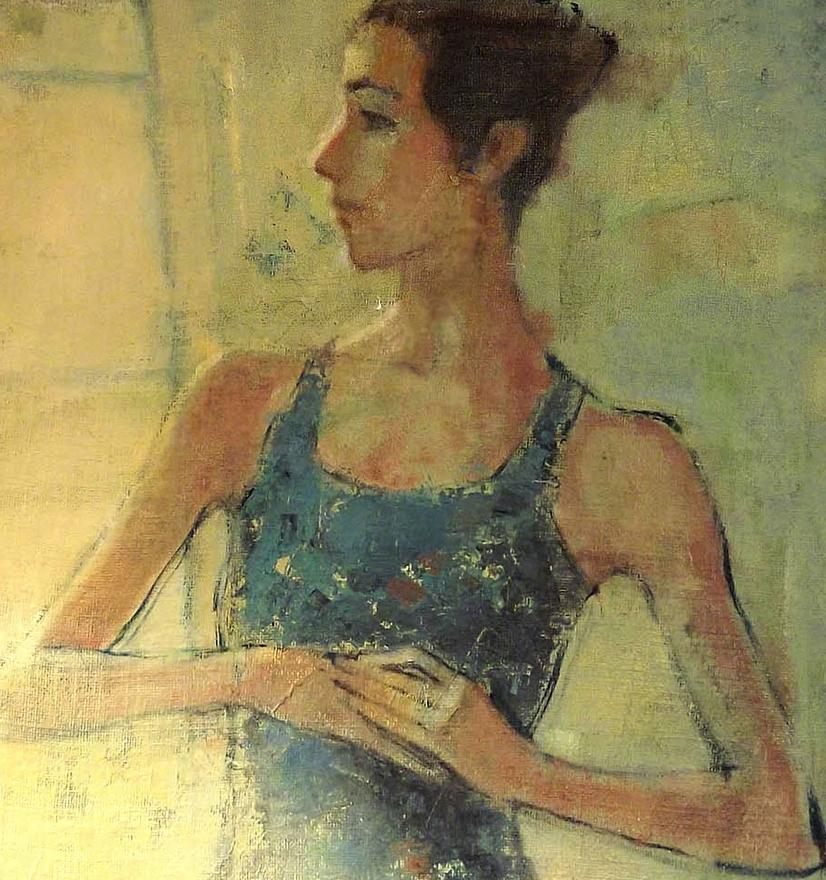

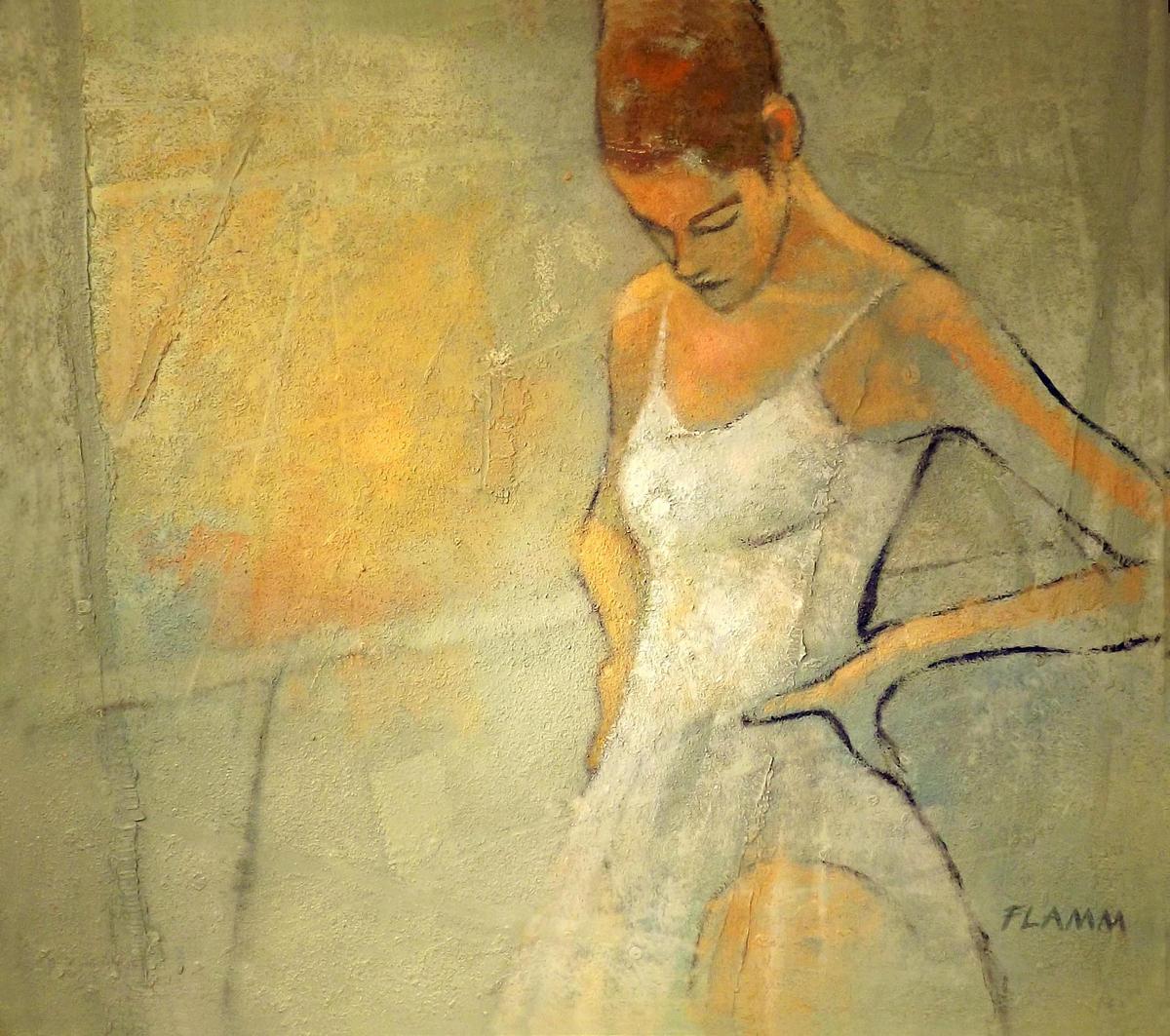

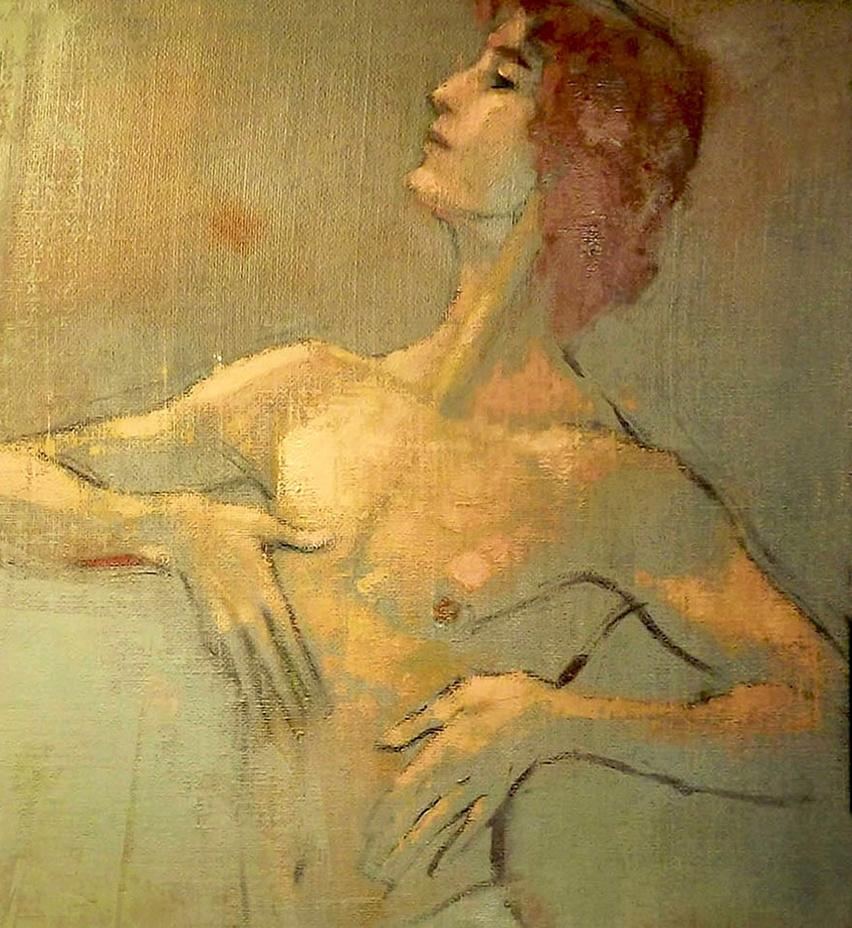

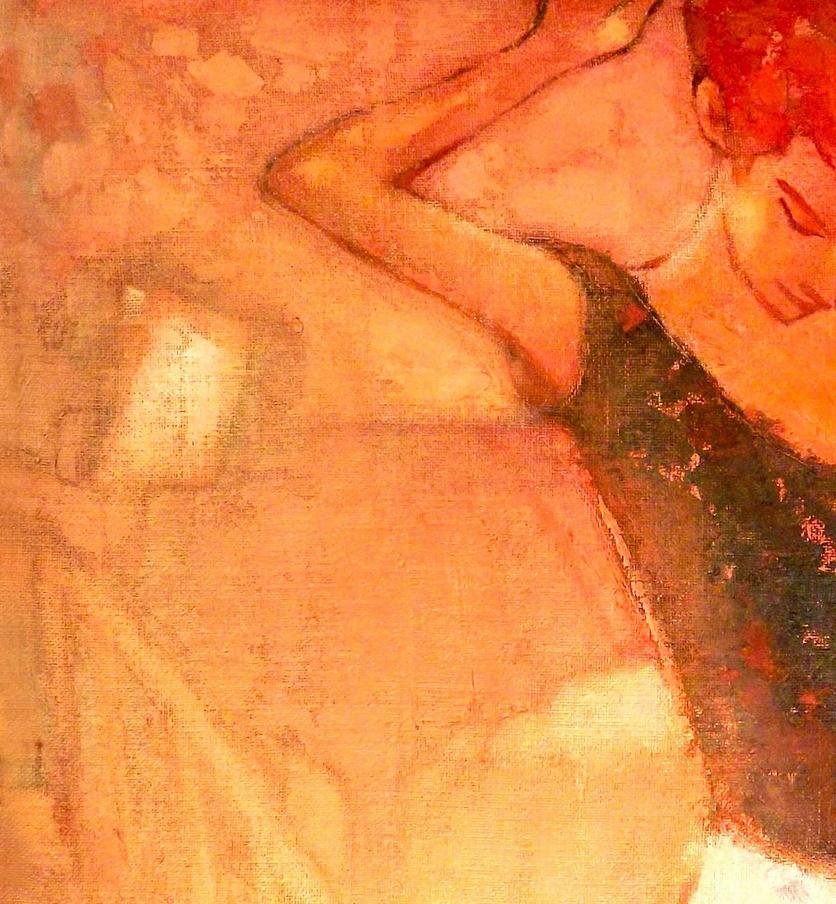

Ferenc Flamm Hungary/ United Kingdom

Ferenc Flamm grew up in Budapest and from an early age fell in love with art, music and dance. His interest continued to mature during his education at The Art College of Budapest and The Hugari- an Academy of Fine Arts, where he closely studied anatomy and movement through the legacy of Leonardo da Vinci and many other great classical masters. In 1976 Ferenc moved to Sweden, married and formed a family, while at the same time finding his feet as a graphic designer and fine artist. Over the past 15 years, he has returned increasingly to his artistic roots; painting portraits, commissions and accomplishing his own art projects. His work has been displayed in art galleries on the Broadway, in Soho and at the City Hall in New York, at the U.S. Congress on Capitol Hill in Washington D.C., in Orlando and Fort Lauderdale in Florida, at the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center in Dallas and in Long Island. He participated in an exhibition at the Mall Galleries, London, and had solo exhibition at the Balint House in Budapest, in Stockholm, Lund and also at the Palace House and the Concert Hall of Gothenburg. During the past year Ferenc has started to focus on one of his favorite themes; the performing arts; ballet and music. He often visited the rehearsals at the Gothenburg Opera, the Ballet Academy and The Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra at the Concert Hall. He made studies, sketches and took photographs in order to create a visual journey into the world of stage arts, particularly to portray the work behind a stage performance.

Manifesting itself in many different ways my work hovers between notions of installation, the sculptural and the participatory. It evolves out of a core relationship with listening as a critical practice, and sound as a physical, spatial and tangible material. While my practice is predominantly sound based, it is consistently informed by a visual art history and context. When exhibited, the work straddles a range of intersecting formal, spatial, sonic and art historical interests. Combining multiple recording methodologies, alongside contemporary audio technologies, my practice draws out the relatively silent and various histories of soundmaking and listening.

As my practice increasingly puts more trust in the invisible, possible worlds of the ‘sonic’ I do not intend for it to be a call for anti-materialism or antirealism, quite the contrary. In its shadow-less world, it occupies real space, and has the ability to be as brutally present as any visual material/object, or as quietly unobtrusive as the image. For me, it’s not a material of clarity or purity, but of the gritty, mucky substances of being.

I worked for a decade as a singer, songwriter, and musician. One artistic/technological project I developed and managed for several years back then was a phone machine and service that I called Phonesong. (At first, actually, I called it Phonestonesong, but I soon decided that was a bit weedy.) It allowed people to call and listen to my songs, which I changed each week. It got some media attention in Boston, and some around the U.S., and for a while received 15,000 calls a year.

SQUEEZESHOT is a successor to that. I think that in all our lives there is a degree of synesthesia at work, each of our senses impacting the others. In a more or less subtle way, we hear what we see, see what we hear, verbalize to ourselves what we think and feel, think and feel what we verbalize, and so on. About anything that we experience, our perception and consciousness speak to us in one voice and, at the same time, in many voices at once. They sing to us solo and in chorus, in our own voice(s) and in the voice(s) that we hear around us—the music of our spheres. Not that there aren’t differences between how sound and vision communicate to us, and in how we use them to communicate, but there’s also that commonality. The two entwine with each other, and enhance each other, enlarging our experience.

I once attended, decades ago, a rather large celebration marking the end of another school year, at a lovely, bucolic farm a few miles outside my hometown of Middleton, Wisconsin. While I had indulged in nothing more dramatic than cheap beer, I was especially intoxicated by the dawn of another summer vDance photography opened up to me when I discovered contemporary dance. I attended a studio showing and immediately fell in love with what I experiencedphysical touch and encounter, moments of ephemeral beauty, new territory to explore and dive into. In the beginning I documented dance on stage or in reherarsals and felt connected to the performers, breathing and moving with them in sync. At some point though, I lost interested in dance photography, it didn't touch me the same way it did initially. I became more aware of the person behind the performer, the inner story, and less of the style of a certain move. Back then I was a contemporary dance student myself and discovered Butoh, an avant- garde performance art in postwar Japan. I had a truly inspiring teacher, Ko Murobushi, and learned to see and to witness the unseen, to go beyond shape and judgment, to experience my body as a landscape and my senses as a whole, including all that cultural upbringing had closed off in early days.

John Cage wrote in his Lectures on Something and Nothing that "[...] the important questions are answered by not liking only but disliking and accepting equally what one likes and dislikes. Otherwise there is no access to the dark night of the soul."

I got my first set of oil paints when I was about 10 years old and started to learn how to paint with them. Later I went to study painting in art school, but I was curios to learn other techniques like sculpture and photography too. My way of self expression has always been the visual kind. The process of starting a new project always begins with an idea. Sometimes ideas come to me easily and almost fully developed, but often it can take some time and I just have to wait while the ideas slowly develop in my mind. After getting the idea the rest is trying to execute it. The end result can be different from what I was planning at first, the work processes are variable and I want to leave room for surprises and chances. I often have many projects running simultaneously. I'm a bit impatient person, so hopping from photography to oil painting or making a short film suits me. Sometimes I wish I would be interested in one thing only, in example painting or photography, so I could really concentrate to that technique, but I find so many things interesting and get easily inspired. If I don't get to finish a project efficiently and in a reasonable time frame, I have a bad habit of never finishing it. The moment has gone and I have already moved on to other fresher ideas.

Special thanks to: Charlotte Seegers, Martin Gantman, Krzysztof Kaczmar, Tracey Snelling, Nicolas Vionnet, Genevieve Favre Petroff, Christopher Marsh, Adam Popli, Marilyn Wylder, Marya Vyrra, Gemma Pepper, Maria Osuna, Hannah Hiaseen and Scarlett Bowman, Yelena York Tonoyan, Edgar Askelovic, Kelsey Sheaffer and Robert Gschwantner.

Lives and works in Berlin, Germany

My multidisciplinary education is an important aspect of my work. Already during my studies, I recognized that I’m interested in mixing analog and digital techniques, and in general in intermediality. Every technique brings another range of topics/aesthetics and another potentiality for expression. But the free switching and mixing between media came slowly with time. I am a child of the times “before the digital revolution,” which is also a reason why I like to move between these two worlds. It’s quite natural for me.

When I think about my Polish background, I’m reminded firstly of the transformative times

Marcelina Wellmer is operating at the edge of video, installation and painting. Her works are dealing with the relation of humans and with the interference of information and media, crossing the border from analog to digital and vice versa. Part of her creation is to play with those edges of media and to amplify their very own characteristics. Wellmer reuses lost and recovered data files and IT hardware. She also use randomness as a important key element of creation. In an erroneous process of encoding and decoding, new perspectives get revealed. Her works were showed in several exhibitions in Europa, Australia, Canada, USA and Japan.

Marcelina Wellmerduring my artistic education. When I studied in the 90s, my academy was some years behind the latest trends, but still there was always a strong connection to Germany. The actions and presentations of internationally famous artists like Fluxus, for example, in the Akumulator Gallery in Poznan, were still truly present. And many of us saw Beuys as the true master.

Thinking about my Polish roots and aesthetic I think in general Poland still has a problem of “form.” As Gombrowicz, our famous writer once said, “I want to live there, where a human is a manufacturer of the form, not its slave.” He emigrated. The aesthetic in Poland was, for me at that time, something still influenced by the romantic tradition and temporary politics, not especially hot or cold, just lukewarm not defined enough. I always knew that I wanted to speak a strong, cold, minimalistic language and build very defined forms. And here inspirations from contemporary German culture, especially the music scene connected to techno, new wave, and electro, were decisive for me. Let’s say I was always a fan of Kraftwerk.

I don’t know if a medium can exhaust itself in general, but I know for me, and that’s very personal, at some point in time my medium was in fact exhausted. At that moment during my studies, when I was painting large format and had presented paintings at Mil-Art Gallery and the

Scanned_Image / detail / 2015

Polish National Bank in Poznan, I got the feeling that it was too easy a way for me to do art. I thought, I have to learn many more techniques that will give me more possibilities for expressing my ideas. This is a very individual thing. Many people can go very deep into one medium, and they can find there very interesting things and tell interesting stories. But I was interested in trying everything possible. It was only later, as I suggested, that I started to mix different techniques to find new ways of expressing my ideas.

I was always interested in many kinds of dimensionality. My mother is a sculptor, and as a child I already played around building some “sculptures.” Later on, I acted some years in off-scene theaters in Poland and Scotland, and I saw how great it is to work with the mixing of light, music, and space. I was also interested in literature, philosophical and spiritual ideas, and with time those multi-/interdisciplinary circuits brought me to a kind of conceptual thinking. So yes, in my case, it’s clear that the whole lifeexperience construction brought me to this way of dealing with media.

Let’s say there are different processes for different works, but yes, some points in the process apply to each other. Mostly, the work starts from one thought which is inspired by a device, or by phenomena that I observe generally in the world. For this work, it was a device, a scanner. I was scanning, like many people commonly do, a lot of paper. In the darkness, I always admired its minimalistic light. So I wanted to do something with it, because it was beautiful for me. First, I started to

experiment with scanning some pieces of mirror and reflecting the scanner light, then with a desk lamp.

These experiments were a base for my painting series, Scanned_Image-paintings. Later, I came to the conclusion that instead of the lamp I wanted to use another scanner’s light it’s useful for making an autonomous circuit. I wanted to avoid a human aspect and talk about the life of machines, mirroring a medium in a medium. Then I started to think about broadening the circuit. On my desk at home, I already had a printer, computer, screen, and some other devices. I recognized that it’s interesting to work with everyday stuff, my closest environment that I’m dependent on.

I started thinking about this parallel to the fact of producing and consuming endless amounts of images in our times, technical dependency, social disconnection, processes that we cannot stop, and so on. Always at that point, I start to check and play with the aesthetical borders and characteristics of the media I use. So the process is, let’s say, to explore the own nature of things and their borders and from those facts come further questions and ideas. The work goes on to become extensions in the case of Scanned_Image, for example, a human being is involved in the process. A person who is shredding the scanned/printed image is just the last span in that mechanical circuit. Most visitors shred the print; they don’t take it with them (which is allowed). I think it’s because of the fact that the machine, in this case a shredder, is just there. It’s a provocation to use it. And to check what happens in the end what is the human behavior in reaction to the machines is also part of the process.

I think every kind of new technology can widen our thinking and broaden the horizons of art. For me personally technology makes it possible to experiment with a bigger range of topics and aesthetics. But anyway, there is no need to fetishize technology. We have to think about why we want to use this or that medium or technology, and it’s hopefully not because this is the new, cool trend.

In general, art and technology are already assimilated. That’s why we talk now about postdigital times. But there will always be gaps, transitions, the way forward is going there and back and around the corner between art and technology. The presence of technology started already with photography, mechanical music, and moving images. Dada, later kinetic art, and many other art movements they were all using technology in a playful way. Every new technology brings us a different kind of aesthetics. It’s good to hear what the medium wants to say to us about itself; every medium has a very strong “character.” The medium wants to give us suggestions, sometimes influence us strongly, but still, I believe, it’s good to stay the main scriptwriter. Otherwise, the medium mutates into a fetish, and we are dependent on it. Personally, I’m interested in figures of thoughts that are inspired by technology.

Another topic is the coherence between the ubiquity of technology and art. That’s the other side. Technology makes it possible to produce endless pieces of art: millions of copies of movies or digital prints, videos, even every installation can be rebuilt without artist participation. It’s enough to have a good digital project, and some companies will produce your artwork, and then exactly the same one again for another customer. Actually, if you use a lot of advanced technology as an artist, you are required to use the help of professionals. These processes are getting very commercial, so that’s why I think critical reflection about technology in art is also really needed. It’s not only about mass media, but also about mass art. I think the process of emergence is exactly as important as the final effect. Not only the end statement matters but also the way to it.

For me, everything around me is environment: my studio, the technical devices that I use, the internet, and public space inside and outside. This all has some visible and hidden structure, some visible and hidden patterns and errors. I like to analyze it and translate it into artworks.

I can say that with time I’m more interested in one of these environmental blocks, the socalled public sphere. It’s a really wide idea. Here I have my very own, private philosophy. I’m not especially interested in leaving material traces in public space. The city is an artwork by itself. The whole construction, the whole dependencies, unexpected occurrences. It is a mechanism with an interior composition, depending on the city, it reminds me of different moments in art history, like impressionism, constructivism, futurism, pop art, Arte Povera.

To be interested in the attributes of public space doesn’t automatically mean for me to “install” a durational artwork there. There are of course some good examples of “public art” but a lot of tragic ones too, because it’s mostly custom-made the aesthetic is deeply connected to the fact that those artworks are custom-built, as if “ordered,” for example, by a city government. I personally most admire performative actions in the public sphere which break/brake the daily cycle. The ephemerality of these actions respond for me in a good way with the character of the public sphere. That’s

why I’m very into all Fluxus-like action. It’s really invigorating!

Sometimes the differences between cities are not so obvious. That’s why it’s good to use some tools to find the “sound” and “composition” of the place. In Berlin and Warsaw, I used GPS and sound recordings to check the differences in the hidden patterns. That was the base for my work 52.5200 ° N, 13.4050 ° E 52.2297 ° N, 21.0122 ° E31.08. And also, the body moving in public space is something special and different for me, almost as if I were in the studio making an artwork. That was a new experience the first time in years I had a really good feeling due to moving around in the outside place I was fully aware of my own body and the path I was passing at that very moment. It was without any rush, and this special attention and observation put me in a very good mood.

I think the role of an artist has changed throughout the course of history. I don’t think that media are changing the role of the artist, but they are changing the artistic process of course. In general, technology is changing history, our surroundings, and us all.

But yes, through this intensity of global communication we can think and talk about phenomena in a different way, and that richness is bringing more possibilities for recontextualization. The context is getting bigger, and so is the recontextualization. But those artistic practices started already at the beginning of the 20th century with Dada, Duchamp, later pop art. We are all the heirs of this.

When we think about the role of the artist in art history, we see many different roles throughout time, and most of them weren’t really freely chosen by the artist. There are always some institutions, politics, important persons, other dependencies behind it. And they often decide if it’s the time for moralistic admonitions, social visionaries, social critics, pleasure givers, or some “individuality” preachers. Now we live in global times and we have all these roles at the same time, depending upon which part of the world we live in this or that role is still more or less preferable. Important institutions, curators, art dealers, have their own preferences and visions. I think we should be very careful about it. Dependencies are the ongoing companion for most artists in history, as well as now, and it’s good to stay attentive about it. But there are still some generally positive paths throughout art history connected to the role of the artist like stimulating sensitivities, shedding light on hidden aspects of life/the world, and looking for new visual forms which are connected to contemporary times. Today, in times of globalized information, some artists understand their role as moral stimulators, but I’m far from this kind of romantic thinking.

Here, I’d like to say a few words about the category of new media actually, it’s not really useful. New technologies appear every day, companies work hard to bring more “happiness” and “fun” into our lives. The results of these efforts influence us constantly. We are running behind this process. All that was new yesterday is old today; that’s how capitalism works. Arduino, Raspberry Pi, sensors, simple coding that’s already daily stuff for Western artists. The generation of digital natives is already growing.

I think we really have to pay attention now, to ask ourselves about the sense of using all these technologies that are often coming from not really ecological or responsible sources. And also what kind of images do we produce, what is their influence on the world? I’ve asked myself these questions often in recent times, and they will influence more and more my

artistic process. The time of technology’s innocent childhood is surely behind us. I feel like switching into post-materialism, new simplicity, new intimacy important aspects for me. That will be my very personal “new sensibility.”

Yes, I believe that this kind of pseudorandomness that I use in DUST and some other works these unexpected, surprising behaviours is giving much greater freedom to perceive the work, and any kind of freedom gives you more possibilities to search for meanings. It also helps to rethink our expectation for the artwork and, in general, our sensation. We are scared about unpredictable behaviours. Randomness is for me something that makes the piece more “alive.” We cannot say exactly what the future will bring us, even if we plan everything out in a precise way. There is still a huge amount of randomness. And that’s why I like to use it; it feels to me much more “natural.” I put some general schematics there. Everything around us has some schema; you can’t get away from this. But then inside the schema things still happen within some degree of freedom.

I have to explain shortly why I’m talking about pseudo-randomness. Some rules always have to be written down, like a range of speed, a kind of movement, colors, a space to move. There are always some parameters, just like in our everyday physical world. Actually, my work Error 404 502 410 is the closest to pure randomness, yet not 100% of the way there. The arm of the hard disc stops when the device gets tired of looking for the right position on the disc to start some proper process of reading data. The stop never happens at exactly the same moment. It’s

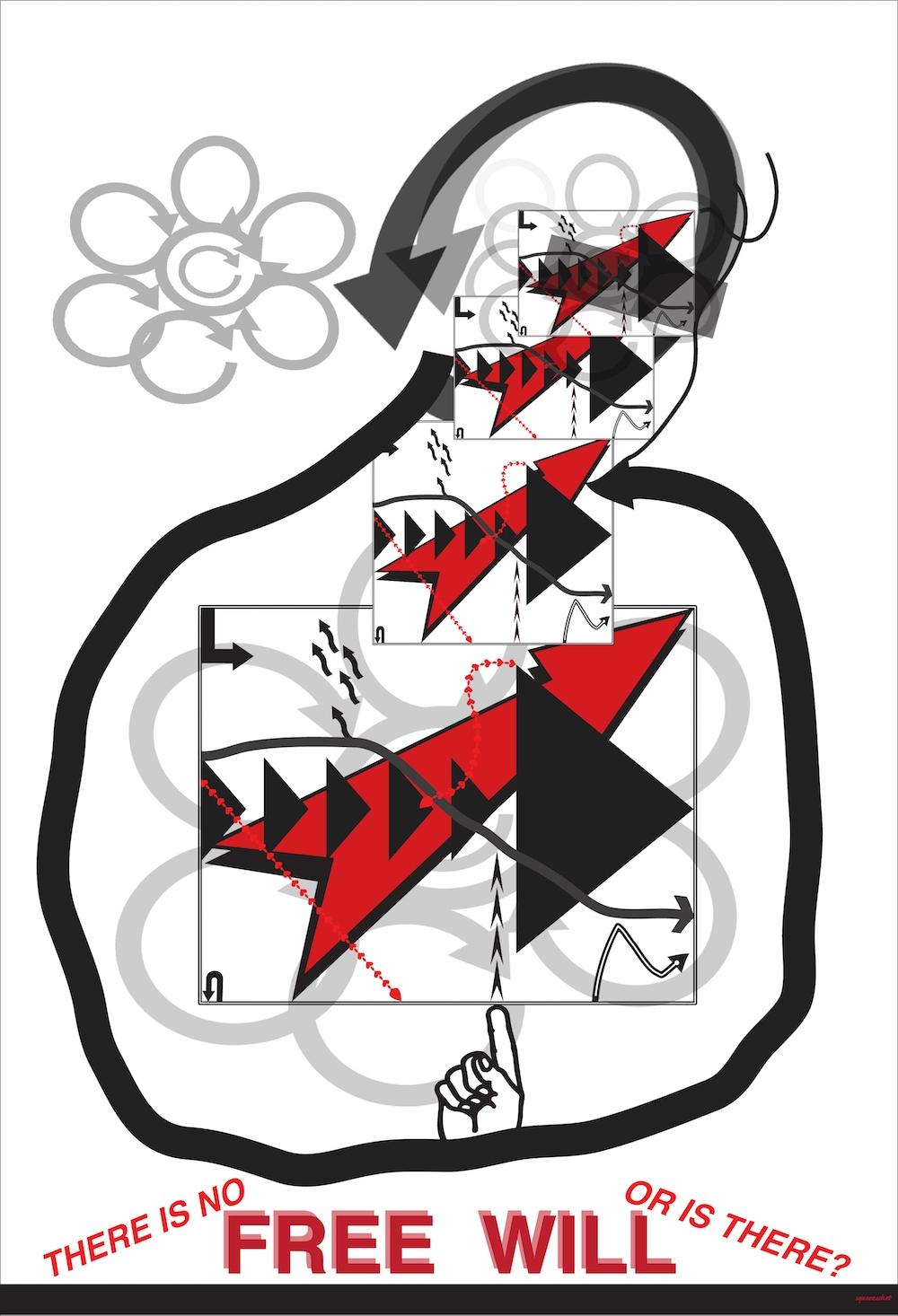

like roulette. There are no coded parameters: this process is dependent on the physical distortion of the disk. The laser-etched numbers stop the arm. But here a physicist would say: there are some rules as to why it happens at exactly this moment; there is a mathematical pattern. It’s just us laypeople who don’t see and understand this. So after researching randomness through my works, I’ve come to recognize that pure randomness doesn’t exist in our physical world of big objects. As I read, some mathematicians have the same opinion that randomness doesn’t exist at all. It’s also possible that in quantum physics randomness is an illusion just because we don’t understand the physics of very small objects. Anyway, my works are far away from those kinds of small objects, so here the rules are clear: this is a pseudo-randomness similar to a pseudo-random number generator.

Through my works, I look for patterns hidden behind the surface of reality, and I believe that sharing these observations in an interesting way can stimulate a dialog with the audience. We all share the same environment, but we see things in different ways. I talk a lot with people during my exhibitions, festivals, and I like to hear their reflections and opinions. It was very interesting to hear that Scanned_Image is talking about “birth and death,” or, “It’s so useless, like my daily work,” and similar things. It’s important for me to

communicate my perspectives in a formal, well done, and understandably clear way, so that the audience can stay interested enough to come to their own conclusions and hopefully start a conversation about how they perceive the contemporary world.

There is a series of works titled RGB, which is even more directly oriented toward a dialog with the viewer. In these works, video with a randomness factor is projected on acrylic paintings. At first glance it’s impossible to recognize what’s happening on the surface. The video mapping is very exact, and the three main light colors red, green, and blue fade into each other very slowly. Everybody expects to catch when the change happens, but it’s not possible. It’s too slow for the eye-brain construct. Only when the viewer is momentarily not watching the piece and then looks back at it can they see the change. People are surprised by their own perception and want to catch the moment with all their might. Here, involving audience expectations was very clear from my side.

Another experience with audiences is that many people want to understand exactly what happens and what is the “right” sense of the work. But understanding how it works is not equal to understanding the “right” meaning. There is no “right” meaning at all. I hope that its interpretation is endless. Some viewers are even irritated if they don’t understand immediately how the work “works.” Here, Scanned_Image is exemplary. In Augsburg at the LAB30 Festival, after the second day of the exhibition, somebody disrupted the piece! Part of the hardware was messed up, and the papers and the shredded waste spread all over the room. It looked like somebody got really angry with it all! Another time, somebody jumped on Missing Files, which was lying down on the floor in the communal gallery weisser elephant in Berlin. I understood this also as a kind of protest. So it’s good to be careful what kind of nonunderstandable experience you serve to the public. But joking aside, I always want the audience to be able to participate with two experiences: the intellectual and the aesthetical,

feeling free to interpret without asking me what it’s all about. And yes, I hope the pseudorandomness helps to keep the work more open.

I think I will continue to, and even more intensely, exercise this complicated figure between simplicity and complexity. The ecological and post-materialist aspect connected to some very local specifications will be more present in my work. But I will still use intermediality and analog-digital translation. My work will more and more show the circuit of emergence, disruption, and dissolution, and use the connections of objects to talk about processes and ideas.

After traveling to Japan this year, I’ve got many inspirations for new ways of mixing digital and analog phenomena, and also touch through a clash between handmade materials/objects and mass media technological ready-mades. I want to for sure spend some more time in Japan this year. The concentrated, focused atmosphere connected with amazingly strange contrasts between things inspires me a lot. Also, the Japanese way of mixing analog and digital ways of living is very interesting. But at this moment, I have to do some contemporary stuff, like preparing Scanned_Image for a show in Spektrum Media Art Center in Berlin [http://spektrumberlin.de/home.html], and I’m working until summer on video material that’s dedicated to experimental music from China. Soon, I’m leaving Berlin to work there with with Chinese musicians and play a show in Beijing. I’m sure I will get a lot of new, exciting inspirations there. I will leave the process running and let myself be surprised by the hidden nature of things.

Thank you!

An interview by , curator and curator

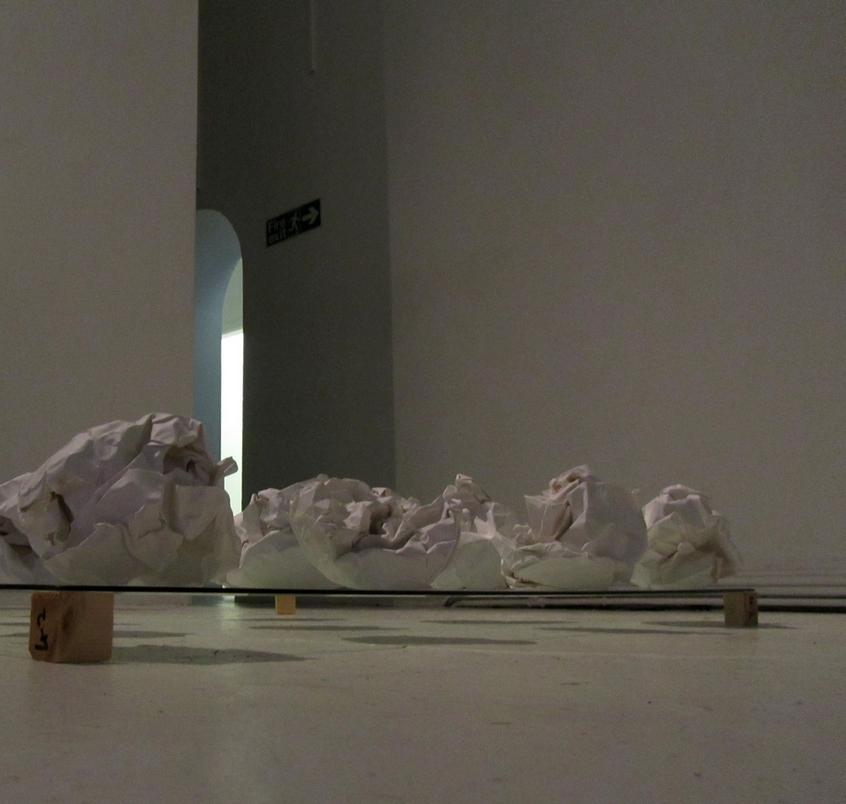

Warsaw-Berlin residency at TU foundation exhibition montage / Warsaw 2016

Warsaw-Berlin residency at TU foundation exhibition montage / Warsaw 2016

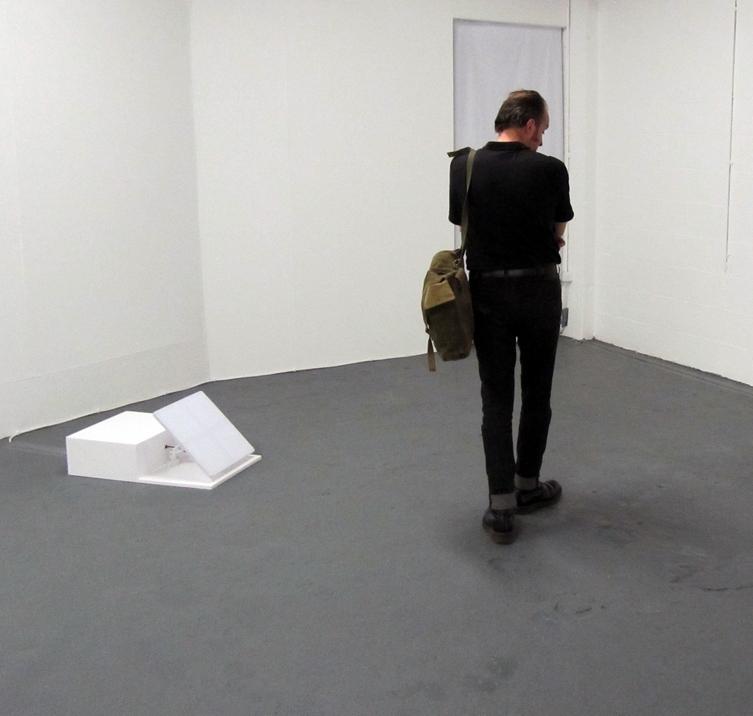

Play it by Ear, Installation View, 2015

Image courtesy of Artist

Lives and works in Dublin, Ireland

Secret, Installation View, 2014

Image courtesy of Artist

Secret, Installation View, 2014

Image courtesy of Artist

My formal education has influenced the way I approach my work in many ways. I completed my BA in Fine Art in an extremely small college in a town called Gorey in the southeast of Ireland. I think at the time the whole college might have only had about 50 students. Regardless of its size, however, there was a wonderfully diverse team of staff in place and an extremely ambitious and committed community of students. Throughout these formative years, I feel I was lucky to be working with members of staff

who felt a real sense for the importance of art history, which I still feel is important today.

After graduating I took a year off to reevaluate my practice before embarking on my MFA at NCAD under the supervision of another wonderful artist Susan MacWilliam. It was during these years I began to focus my practice on the history of sound-making and the aesthetics of the sonic. It was also during these years however I realised that there was a whole segment of knowledge I was lacking

Richard Carrin which I felt I needed if I was to continue my practice after leaving the safety of an art institution: The world of galleries, curators and continuous applications. So, I pushed myself in this direction completing a year's work-placement at the Irish Museum of Modern Art under the guidance of Rachel Thomas; Senior Curator & Head of Exhibitions as well as completing a PGDip in Business in Cultural Event Management from the Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Dublin. So, taking the above into consideration and trying to answer your more specific questions, I think I now approach my work(s) with the view that they may have a much longer life-cycle than I previously thought and one I am not necessarily in control of. Saying this, however, for me to productively work in the studio I try to leave as much of the above at home in the attempt to have as genuine as possible engagement with the development of the work in the moment of making it.

To be honest I have never thought of my work as multi-disciplinary or consciously made decisions to cross media or mediums. They usually just evolve over a period of time, like a conversation but a conversation with myself perhaps. I always begin with listening, whether I’m in the studio, out for a

walk, sitting in a café etc. I have often been told by friends that I can have a whole conversation with them while being immersed ‘sonically’ in some stranger's life the other side of the room, the trickles of a fountain or squeak of a hinge. I usually have my recorder with me and if something grabs me I begin recording. Other times I specifically put myself in environments of particular interest and participate in the environments sound-making more consciously, like Pythagoras’ Cave for example. Usually, the sounds are all brought back to my studio where I consistently listen to them over and over until I have a sound I am in some way happy with. The work never begins with an idea or pre-mapped plan but constantly shifts the more I spend time with it.

It’s only when I am invited to exhibit work do the pieces themselves become in some way resolved. It is at this point I engage with the physicality and spatiality of sound and this usually evolves out of a conversation between the ‘sound work’ and the architecture of the gallery or exhibition space. Often the first time I experience the work in its ‘finished’ form may be the day before an exhibition opening.

Yes, Secret I think is an unusual work and feel it kind of sticks out in relation to my practice as a whole. It was developed at a time when I was obsessed with considering the history of sound within a visual art history and became increasingly interested in the work of Robert Morris, especially his work ‘Box with the sound of its own making’. The reason I became interested in this specific work was I

was using a similar process of recording the making of the work in one of my earlier pieces Construct? Unlike Morris’ work, however, Secret doesn’t possess the sound of its own making but rather facilitates a participatory process allowing for the sounds of ‘our own making’. What I mean by this is that Secret doesn’t have any sound and is essentially a silent work. However, it does invite people to interact/perform for each other in a subtle way via the work.

Secret is essentially a wooden box sitting on a plinth. Inside however are two omnidirectional microphones set up to provide one live binaural feed to two sets of headphones. Only slightly amplified, it picks up the sound of the participant's hands rubbing, tapping and scratching the box. As it is one live feed, each participant hears and ‘feels’ the sounds of the other participant's hands gently moving or caressing their head. As the performance is not recorded, the sound they create only lasts for as long they engage with each other and the piece etc.

and logic. For example, you mention I spent most of my college years in the painting department, which is true. This came about as there was no option of a sound or listening department and the painting department was the closest thing I could find in approach to the philosophical, ontological and phenomenological interests I had in making work. This I presume is a direct result of art colleges falling under the umbrella term of visual culture and therefore take the approach of a visual led sensibility and logic.

Gemma Corradi Fiumara discusses this evolvement in depth in her book ‘The Other Side of Language; A Philosophy of Listening’ where she discusses how Western societies have become accustomed to mechanisms and logos of expression, speaking and reasoning. This according to Fiumara is a half logic, a logic not conducive of listening in the way in which it once had. She discusses this through historic developments of the term ‘logos’ in which was once ‘legein’. A more wholesome term that included a process of ‘gathering’ alongside ‘saying’ in the formulation of knowledge. A disappeared process in our current term ‘logos’. By not holding a process of listening on equal footing, we are diminishing the possibilities of truer forms of dialogue while becoming subordinately dependent on the power, domination and dialectics of saying. While all this seems very abstract, we can see the effects of this play out in very real terms within the everyday. For example, if we look at the pinnacles of our societies, Dáil Eireann or the Houses of Parliament, they are currently based on a structure of controlled speaking times.

I’m delighted you have referred to Marshall McLuhan here because I think he is right when he points this out. I do believe that Western societies have over time moved and become more reliant on a visual sensibility

Yes, you are right to refer here to my work ‘Play it by Ear’ which does in a way attempt to approach this subject. Play it by Ear was recorded during my research visit to Pythagoras’ Cave on the Greek island of Samos. It was an attempt to experience the sonic environment that Pythagoras may have experienced while teaching his pupils from

behind a curtain. It was also an attempt to enquire into these early interventions of acousmatics that it is said Pythagoras practiced. At this time I was also researching various histories of listening as a critical practice and became very interested in the research/discoveries led by Iegor Reznikoff. Reznikoff proposes in his text ‘On Primitive Elements of Musical Meaning’ that there are direct relationships between the images and placement of cave paintings and the sonic resonance of the cave itself. For example, he proposes that listening is our most primitive sense and that the Palaeolithic people engaged primarily with their caves on sonic terms. Using his voice to navigate, Reznikoff discovered that every time he stumbled upon narrow galleries of the cave, with high resonance, there appeared a painted red dot. He also discovered that in small recesses or narrow hollows that resonated strongly with low sounds, appeared paintings of animals which make similar sounds, for example, a bison.

So, getting back to your more specific questions; listening and sound have always worked alongside the visual in inventive ways. It was never a reduction of the visual or less than the image, but something different that often brought forth unseen visualities. However, with Western societies engagement with knowledge from the perspective of the eye, this noisiness has far too often been silenced and we can see this from the dominant perspectives of art history. More recently, however, we can see a reengagement with a sonic sensibility with many authors and artists investigating the term ‘Sonic Art’ and what this might mean.

This is an interesting question and something I have been thinking a lot about lately. For me, I rely a lot on the public sphere and the publicness of sound in relation to gathering my material. Within a contemporary context, the materiality of sound increasingly positions itself as an intriguing and important medium for notions of public art. The invisible mobility of the sonic, its continuous presence and formless form, lends itself to be an important tool to explore, intervene and interrogate visual givens. A lot of urban planning focuses on notions of space and place; what happens within and between buildings, punctuated by architectural design. What is often forgotten about is the acoustic environment and how these architectural punctuations can disable or enable our sense of self as sound-making and listening beings. Sound becomes the public 'in-between' of urban planning, linking together all the consecutive ‘things’ that often remain apart. Therefore, sound plays a crucial role in the production and interactivity of the public sphere by embracing the ‘fluidity’ of ‘publicness’ and the ‘publicness’ of a ‘sonic aesthetic’. It’s the invisible and passing nature of the sonic that makes visible that the infrastructure is not the public. Rather it is the way we as communities interact and participate within and through these infrastructures that the notion of ‘public’ becomes generated.

This conception is not new; it was known for example by Jeremy Bentham when constructing his plans for his Penitentiary Panopticon. At this time, however, the inward-looking world of observation and isolation could not master the social activities of sound and Bentham dropped his idea of placing ‘sound tubes’ from his central tower to each cell as they worked both ways, simultaneously opening up and connecting the central tower of observation to the 'observation' of the prisoners.

In relation to my own work I see an innately sustainable stability within the fluidity of the sonic; one which provides a different sense of knowledge and publicness – one that may not fit comfortably into a visual scheme of quantification but one in which allows for personal, sensory qualities to be illuminated. This I believe is a relationship that reconsiders the primacy of a reflective process [visual aesthetic] to one of a living and motile process [sonic aesthetic]. Taking this approach, I feel generates an immersive engagement with the liveliness of environment, disrupts normative conceptions of reality and actuality by allowing an opening up of a more plural imagination of the world.

It is funny how you selected Residual Error to link with the idea of randomness as it is the one work of mine that was made solely within the controlled confines of my studio. However, I think you are quite right and thinking about how to answer this question from this perspective has led me to discover new insights into this work. Residual Error began with research into both the Pythagorean Comma and Pythagorean Tetraktys. Both these systems rely heavily on mathematics, geometry and logic, anything but randomness. However, through the utilisation of maths, both were attempts to understand or quantify Pythagorean unknowns and from a certain perspective the randomness of being.

The title of the work takes its name from a mathematical mistake made during Pythagoras’ discovery that you could make a musical scale by continuing through the ‘Circle of Fifths’ and dividing down harmonically with the ‘Law of Octaves’ to determine the pitch of each note.

However, Pythagoras’ calculations do not add up correctly and leave a small residual error, in which some say, we can hear if we choose to listen out for it.

So yes, you are quite right that I urge people to elaborate on their personal associations. I feel this is important as I don’t believe the work, in and of itself, holds all the answers. For me, the work participates in the formation of meanings and just like that I like to think that people simultaneously participate, rather than rethink an a priori meaning laid out before them.

Well, I have never been sure what the role of the artist is or if there should be one. However, I think I understand what you mean in relation to technological developments and the opening of global communications. For me, while I think these developments have certainly impacted/enhanced the possibilities for artists to engage with different mediums/media, I believe they have possibly served other sectors of society much more. While many contemporary artists utilise or even challenge the potentials of new media, I find, similarly to how you describe innovation, that there are usually undertones and experiences of ideas and practices that have been around for decades or even centuries.

Taking Angela Bulloch’s quote that you mention, I feel it describes my work Secret in which I spoke a little about earlier but maybe even more so my work Construct? On the

contrary, however, elements of change may not inherently reside in the ‘work’ but yet they continue to evolve and shift. For example, my earlier work MOUNTAIN was recorded back in 2012 at the border crossing from Turkey, looking out to the Greek Island of Samos in the EU. At this time, the border was quite invisible and extremely porous with thousands of people making their way in and out of the EU with ease. This notion of ‘open borders’ captivated me at the time and was something that played a central role in the development of MOUNTAIN. Today, however, we can see how this context has changed, with these invisible lines/borders increasingly becoming more visible and concrete. So of course, when I now experience MOUNTAIN, it brings up a whole set of different meanings and associations than it once did and from this perspective, I feel a quote from Irit Rogoff may be more appropriate.

In a “turn,” we shift away from something or towards or around something, and it is we who are in movement, rather than it. Something is activated in us, perhaps even actualized, as we move. And so I am tempted to turn away from the various emulations of an aesthetics of pedagogy that have taken place in so many forums and platforms around us in recent years, and towards the very drive to turn.

My background also plays a large part in this as I have spent over half my life living alongside people who have been clinically diagnosed with various degrees of mental illness from Depression, Bipolar and Paranoid Schizophrenia. Willingly embracing this, daily you enter and exit many invisible, possible worlds. Ones I may not be able to see or listen to for myself, but ones I partake in, which consequently affect and alter my reality and through my participation alters the world that is both invisible and inaudible to me etc.

From this perspective, I suppose my work aims to consciously and simultaneously bring the worlds of reality and imagination together if they do not already exist as one.

attempted to open a work to an audience, the more I began to control to open environment in which I was inviting the audience into etc. So, in my more recent works and especially in the early stage of producing work, notions of audience reception do not enter at all into the equation and certainly not as a component for decision-making. My process begins with listening; it’s a personal and intuitive engagement until I stop.

On the other hand, in terms of being invited to exhibit work, my thought process shifts and begins to think about the logistics of the space itself. I begin to engage with its architecture, sonic environment and how the flow/movement of people may take place within its context. The flow and movement of people through space becomes important for me at this stage and becomes part of the conversation in how the work may be installed or realised. From this perspective, audience reception can play a part in my decision-making process.

This is a difficult question to answer as my work evolves at different times and within different contexts. Notions of audience reception/participation played a much more crucial role in my earlier works. However, over time I came to the belief that the more I

Thank you, abens, it has been a privilege to be able to chat with you. Yes, currently I am working on several projects and will be participating in an exciting, upcoming international exhibition in Ireland later this year. I have also been invited to develop a new sound installation, which will take the form of a solo exhibition in a gallery space in London in 2018 which is great and something I am looking forward to. I don’t want to say too much about these at this stage; however, people can keep up to date with these developments through the news section of my website:

An interview by , curator and curator

Lives and works in Vancouver, Canada

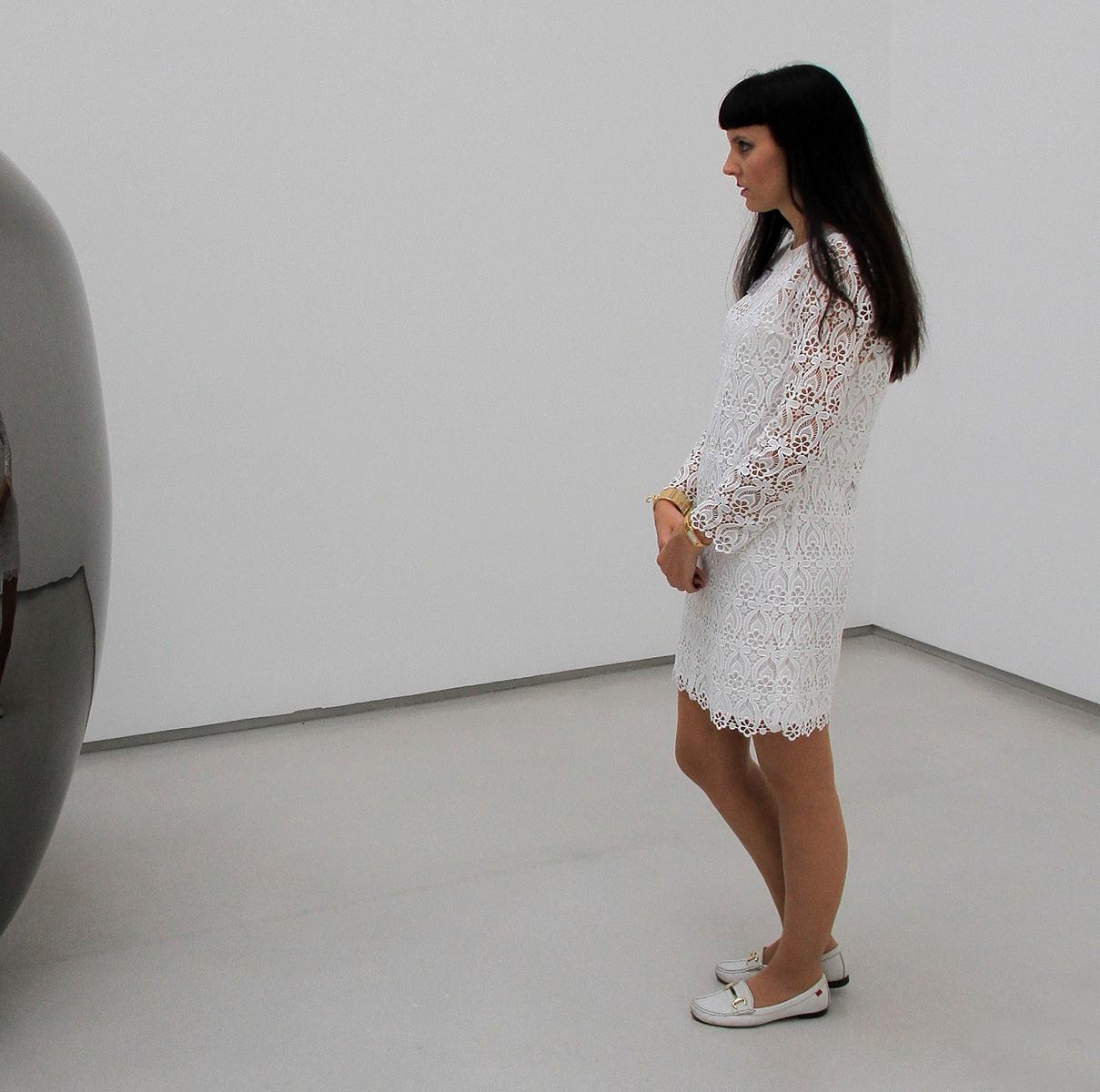

Holly w Damien Hirst, FIAC Paris 2012, photo by Murray Fraeme

Holly w Damien Hirst, FIAC Paris 2012, photo by Murray Fraeme

Holly Marie Armishaw

Holly Marie Armishaw

I believe it is an asset to any profession to know ones industry from every angle. So, I have volunteered in galleries, served on student councils, curated shows presided on boards of arts organizations, written art criticism and theory, and organized everything from panel discussions on contemporary art to private collection visits. While each of these positions or projects has been challenging, they have also been quite rewarding.

Being involved in various positions within the art community has enabled me to assist in providing other artists with opportunities and a voice within our various institutions. For example, CARFAC (Canadian Artists' Representation/Le Front des Artistes Canadiens) is responsible for ensuring that artists receive payment for exhibiting at non-profit galleries, whereas in the U.S. artists often have to pay. My position on the Board of Directors of the CASV (Contemporary Art Society of Vancouver) provided a challenging and informative experience. It afforded me the opportunity to expand my network and to develop many cherished long-term friendships. In 2014 I organized and led a weeklong tour of Paris’ contemporary art scene for a dozen Vancouver-based art collectors. It was a wonderful to work with our consulates and an opportunity to share my passion for French art and culture with a Canadian audience.

Another key factor in my practice has been travelling to attend various international art fairs and biennales. I thrive on the opportunity to experience the crème de la crème of the world’s most influential artists

all beneath one roof. This always proves to be a riveting experience providing both inspiration and a sense of how my own work fits into the larger context of the art world. Drawing inspiration from the works of other artists is something that often pushes me in my own work and is also an experience that compels me to come back and write as I analyze connections between them. Writing has always been an essential part of my practice, and Sotheby’s gave me the tools to sharpen that skill.

I attended art school on the cusp of the digital revolution. At the time that I was completing my photography degree, barely anyone used digital camera, and certainly not art students. I began spending less time in the darkrooms and more time in the computer labs, scanning my film and importing it into Photoshop. Perhaps it was a reaction against Roland Barthes Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction that pushed me away from straight photography and into a modus operandi where I could have more freedom to create my images, rather than merely record them with the camera. Digital imaging

served me well to express subjects that piqued my interest at the time. I began art school with a sideline interest in metaphysics, which led me into philosophical and scientific theories like quantum physics and the Many Worlds Theory. When the first sheep, Dolly, was cloned, it provoked me to explore genetic engineering and the Human Genome Project in my work, illustrating a strong consideration for potential discrimination in the future, such as we saw in the cult classic movie of the time, Gattaca. The concept of immortality has also been a ubiquitous theme in my practice and led me to explore post-human endeavors, such as cryonic suspension. Digital imaging was the perfect tool to express these concepts which there was no way to photograph directly. It has remained one of the most important tools used throughout my art practice.

Post-art school, real life tends to take over. It became extremely difficult to produce work after awhile because of massive student loan debts, the high cost of living in Vancouver, and long work hours. It seems that not everyone can live without art. My work eventually became focused on more immediate and personal concerns than it was previously. The Silencieux series describes a period where I began breaking down physically and mentally, suffering from panic attacks, night terrors, migraines and a host of other maladies. I lost my job as a result and was left with nothing but my camera, computer, and a small suite to live and

work in. I used these three elements, in addition to myself, to create a series self-portraits that described these conflicts between the mind and body, again using digital imaging, but this time to describe the psychological aspects of my own experiences.

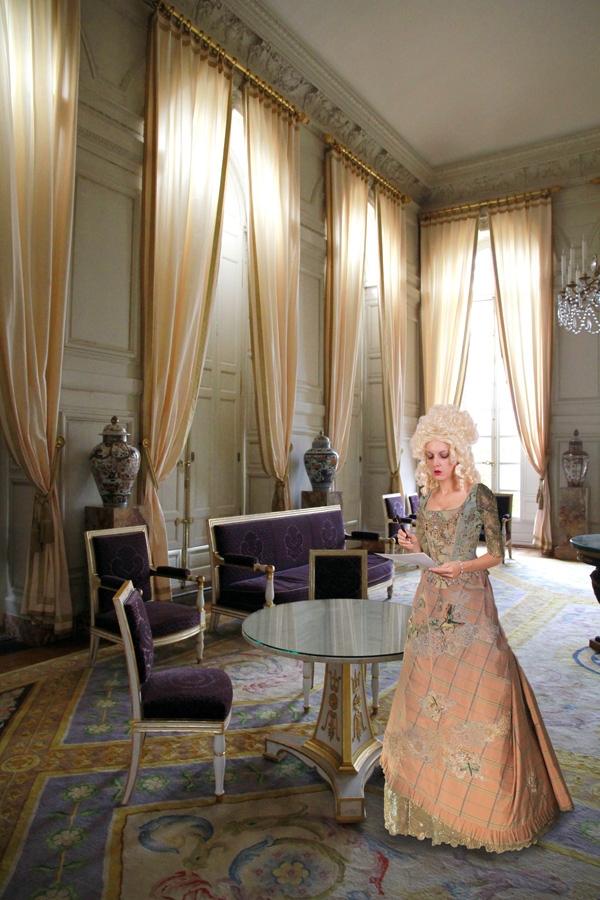

By 2011 I was back on my feet and travelling extensively, producing a massive archive of photographic imagery thanks to the luxury afforded by the proliferation of the digital camera and it’s ability to store thousands of photos. I used some of my photos from Versailles, combined with self-portraits shot in my studio specifically for this purpose, in order to create my Marie Antoinette series. Each image contains a minimum of three photos composited together. Although technically they are selfportraits, it was an intentional shift away from the subjective to an objective focus on the trials and tribulations of another woman. Research once again became a key part of my practice, and I spent two years studying the French Revolution and the life of Marie Antoinette. By highlighting little known facts about her life, I was able to humanize a woman who served history as a convenient scapegoat for the mistakes of generations of monarchist rule.

France’s financial deficit had become an issue years before Marie Antoinette even came to France to marry Louis XVI. Louis XIV and his advisors were much more to blame for France’s financial crisis because they had spent

“Marie Antoinette Declaring Financial Incentive for Women of France to Breastfeed Their Own Children” (2013) 24 x 36” C-Print, Holly Marie Armishaw

“Marie Antoinette Declaring Financial Incentive for Women of France to Breastfeed Their Own Children” (2013) 24 x 36” C-Print, Holly Marie Armishaw

Holly Marie Armishaw contemplating the work of Daniel Firman, FIAC 2012 (photo by Murray Fraeme)

Holly Marie Armishaw contemplating the work of Daniel Firman, FIAC 2012 (photo by Murray Fraeme)

far beyond their means supporting the Americans war of independence against the British, France’s enemy at the time. This was the beginning of my interest in historical revisionism, a strategy that I am still employing in newer bodies of work today.

To answer the first part of your question, I began working on the Repressions series shortly after being diagnosed with PTSD in 2015. Repressions deals with the effects of abuse and trauma on the body and mind. While we commonly associate PTSD with persons who served in the military or who survived a natural disaster, the scope is actually much more diverse. A child who endures repeated abuse at home and cannot escape will suffer the same effects of trauma as a prisoner of war or a hostage situation survivor. That was my situation for ten years growing up and the result is what’s known as complex PTSD. Being perpetually put into a state of flight or fight response is extremely taxing on the body, often

leaving the survivor with an impaired immune system, anxiety, depression, and a host of other disorders, many of which do not appear until later in life. Decades later I still wake up screaming in my sleep from time to time, and have on a few occasions jumped out of a moving vehicle due to trigger responses. Rape survivors or those who endured childhood sexual abuse may not only develop PTSD, but also reproductive disorders, even causing chronic pain as a result of the body’s memory of the trauma it endured. When I confronted my family in 2013 on my history of abuse, not only was no apology offered, but they also completely denied my allegations. I have since estranged myself from them, but the stress and shock from their response (or lack thereof) to incidents that have affected me my entire life has caused further damage to my health. For me art has become a cathartic process in learning to understand and come to terms with the world. And, as the second wave of feminism stated “the personal is political”. I know that I am not alone and by sharing my personal experiences in a symbolic way, I am able to open up dialogue about the widespread abuse of girls and women. It’s easy enough to tell survivors to “get over it”, but that contradicts the science behind trauma and abuse. In the Repressions series, remnants from the photos spill over from the image and into frame just as repressed memories from the past spill out into the present.

In response to the second part of your question, you have already previously noted the multiple layers of meaning that runs throughout each work, and this demonstrates the complexity of my creative thought process. Regardless of the style or technique I use in each series of work, the most essential underlying element is existentialism. As a key theme throughout my practice, according to its broadest scope, existentialism examines issues as diverse as selfawareness, individual human experience, immortality, individual purpose, and the nature of existence or reality and truth. Often truths are uncomfortable for many people, and art is a way of bringing them to light in a more delicate manner.

I concur with Orozco’s statement; and I would expand by saying that the most authentic art comes from a place of reality, one that the artist is intimately

familiar with, even if that personal connection is disguised. Of course, metaphysics has taught us that the

nature of reality is subjective. Since the world can never be known through a singular perspective and we all bring

different tools and sets of memories with which to analyze and interpret our existence, it is essential that

contemporary art be produced from a multitude of perspectives. We are each an authority on what we live. Politics in

art signals a state of discontent. The artist who is content and bears no angst against oppressiveness towards

themselves or their community may find satisfaction in making art about art, perhaps about the semiotics of

painting. Anger and discontent are very powerful motivators. In a recent conversation I was told that “art should

"Eggs" (2015-16) 24 x 24" C-Print with Eggshell, Holly Marie Armishaw

respectfully disagree. A look at some of the most important and powerful works

not be about politics; we have journalism for that” to which I mustHolly Marie Armishaw ART Habens

throughout art history are a direct reflection of the conflicts of the time they were created. Examples include Goya’s Disasters of War (1810 to 1820), Picasso’s Guernica (1937), and the Guerilla Girls Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get Into the Met. Museum? (1989). During this key moment in history when we are experiencing a daily assault on democracy it is essential that artists fight for ideals of hard-won liberty and equality in order to secure it for future generations. I am privileged to be an artist in Canada where freedom of speech is protected; a luxury many others around the world live without. Lately I have been developing an interest in Islamic feminism, but as someone who has not lived in an Islamic state, it is not my place to speak for others. As an alternative, I have written on the art of Shirin Neshat, an exiled Iranian artist, who brings the Islamic feminine existence to light for a Western public. Neshat is a powerful political voice in contemporary art, and one that I have great respect for. My father once told me that “art is a self-indulgent profession”. I would like to see contemporary art prove this wrong.

Throughout the history of my practice, I often employed a visual narrative strategy. But with Repressions, I pushed myself to try something different, like learning to speak a second visual language. By using symbolism I was able to deal with sensitive subject matter more comfortably to speak to a female audience, without alienating my male audience. Women are more apt to understand my references in this series, such as using eggs as metaphors for ovules. This was a more poetic approach using universal imagery that was less subjective in representation, therefore allowing more women to enter themselves into the dialogue.

Creating an immersive experience for my audience is becoming increasingly more important in my practice. I have been experimenting with this by creating contemporary uses of trompe l’oeil in some works. Again, this harkens back to the theme of the conflicts between illusion and reality and the blurred line between them. As for contemporary art in the public sphere, I think it’s an essential practice to promote inclusivity and to engage the public with challenging ideas that they might otherwise not be exposed to. I am just beginning to look for opportunities to do public installations with my work.

women are actually treated equally today. I am a feminist not because it is trendy or because of anything I learned in critical studies classes at art school. I am a feminist because I spent every day growing up having my older brother try to beat any sense of equality out of me, to break me and force me into submissiveness. (It’s not unusual that women who resist will face the most extreme measures of coerciveness.) And yet, I realized at a very young age, I had an innate sense that I was equal or better than my abusers. I am a feminist because as a teenager I worked to put myself through private school and was subjected to sexual harassment constantly in my workplace. I am a feminist because my ambitions as an athlete in my teens deteriorated rapidly after a sexual assault when I realized that no matter how fit or strong I was, there would always be some man who was stronger than me. I had to be smarter than them to survive! As I headed into adulthood, I found myself gravitating towards an intellectual and creative career path and resettling in communities where men were well educated and more enlightened. I am a feminist today in hopes that your daughters can grow up in a fairer world than I did, one where they are valued as human beings that hold as much potential as their male counterparts.

It is a deluded and dishonest perception if anyone thinks that

The dehumanization of women has been a timeless struggle, one that transcends not only time, but also race

“Marie Antoinette – Under Pressure to Produce an Heir Throughout 7 Years of Unconsummated Marriage” (2011-12) 24 x 36” Metallic C-Print Holly Marie Armishaw

“Marie Antoinette – Under Pressure to Produce an Heir Throughout 7 Years of Unconsummated Marriage” (2011-12) 24 x 36” Metallic C-Print Holly Marie Armishaw

and class. Even the most privileged women suffer as a result of the gender norms of their time, as I demonstrated in the Marie Antoinette series.

I don’t believe that my position as a women provides my work with any

special value or additional meaning other than being in stark contrast to decades of art history, from which the majority has been produced from a male perspective. When I attended my first art history class, I thought “What a

great way to learn about the history of civilization!”. But, if art history only reflects half of humanity, then how accurate and complete is it really? We need women artists to balance the story of human history as much

as we need records of art produced by non-western civilizations.

Tradition has often been a source of oppression for women and many others, whether those traditions are religious or cultural. Contemporariness seeks to scrutinize and, in many cases, break those traditions. So, yes, there is a strong contrast between them. As an atheist, I feel extremely liberated from many traditions that would otherwise restrict my freedom of thought and lifestyle, and that would only serve to consume my energies and distract from more meaningful endeavors.

I don’t recognize anything in my works as being fictional. I think that we need to differentiate between illusion and fiction. Even a hallucinogenic experience is a “real” experience to the experiencer. My

intention is often to present allusions to underlying or hypothetical truths through the use of photographic illusion. Sometimes these allusions are in reference to taboo personal truths or historical inaccuracies, while at other times they are more are more playfully reminiscent of the type of truth portrayed in Magritte’s “Ceci n’est pas un pipe” (1948) that examines perception.

I have recently created a series of work that examines the history of the mirror in relationship to photography by using illusion to engage the viewer. The mirror was invented in Murano when glass craftsmen applied silver to one side of plate glass. It is my theory that the invention of the plate glass mirror created a profound new sense of selfawareness. When early viewers of the mirror saw themselves reflected, that experience provided the impetus to preserve the image that they saw for posterity. Louis Daguerre worked feverishly to “fix” that image and soon invented the Daguerreotype, a photographic image produced on a small mirror-like silver surface. In fact, silver nitrate particles are still used in labs for photographic processes today. The Daguerreotype was the first photographic process readily available to the public, thus democratizing the practice of portraiture beyond the upper class that could afford to commission portrait paintings. Who would have thought that today’s mass phenomena of the selfie would have originated in a

glass atelier centuries ago at a small island off the coast of Venice? History has become a keen interest of mine, because it is so rich with signifiers that explain our zeitgeist.

Production of art will continue to embrace new technologies as they consecutively evolve. However, there is also a reactionary effect occurring as we see a return to materiality and a highly skilled hand; the phenomenal paintings of Kehinde Wiley are a great example of this. As an artist whose primary medium is photography, I have been forced to reconsider what that means now in an era where cell phones, filter apps and social media have induced a mass proliferation of the photographic image. I have challenged myself to think about approaching photography differently and it has affected my production, techniques and materials. As previously mentioned throughout this interview, while layers, both literal and conceptual, are still a key element in my work, the literal layers are now created out of tactile materials rather than from photographic ones. This is my way of reacting against the immediacy of the photographic medium. By creating works that require an in-person experience in order to successfully

experience their essence, I am encouraging art connoisseurs to leave their screens and to enter into the gallery space where I may interact with them more directly.

Became a Feminist by Reading

Certainly the work is more successful if the audience can find a relationship to it, and at times I have a certain city or venue in mind while I am creating a series. I assume that you are speaking about my text-based work. In 2011, I began etching nasty little phrases in French using a lyrical font etched onto elegant gilded antique mirrors. These phrases cast a self-reflective scrutiny on the viewers. I had hoped to show that work in France, and would have liked to witness their reaction. The work did reach a Canadian audience, and fortunately we speak many languages here, so there were those that understood. However, with more recent text-based work I am using English, as it is both my first language and spoken across the globe.

Nietzsche. This is text-based work painted with nail polish on watercolor paper on some pieces, and with gold leaf on others. The nail polish was deliberately chosen as a feminine material, and one that has previously been foreign to the art world. Using these materials I have composed quotes by Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and Freud, which I have edited by changing all masculine signifiers to feminine ones. This editing process of inverting assumed gender norms reflects how a woman must read the work of a misogynist in order to still benefit from his words of wisdom, rather than completely dismissing them. These particular philosophical writings had a profound effect on me at a crucial stage of my life, during a point of existential crisis when I was also becoming both an adult and an artist. Though misogynistic, these men's words provided clarity that formed the core of my adult values; their influences both inspired me and brought out a streak of defiance, which, combined with my own personal experiences and existential conclusions, have contributed to my being godless, famliless, and remaining childless, all of which are deliberate and essential to my focus as an artist.

I am very excited to have just completed a new series of work, How I

An interview by , curator and curator

Longines Photography and Sonia Gil Collaboration

An interview by , curator and curator

Longines Photography and Sonia Gil Collaboration

An interview by , curator and curator

My training as an Architect has great influence on my work, it introduced me to Art History and to a large array of graphic techniques and ways of investigating and representing 3D space. It developed my perception as well as my representational ability.

After having completed the basic years I felt I needed more art training, so I started taking classes at the School of Visual Arts of Parque Lage and at the Modern Art Museum of Rio de Janeiro, where I attended classes with Aluisio Carvão, a neoconcrete artist who explored colour as a matter. I feel his meticulous colour exercises were part of my learning process, but after some time, I wanted to work more freely, in a more intuitive way, I was looking for something more fluid. This was when I discovered watercolour.

Sonia GilFor many years, I elected watercolour as my favorite medium, then I moved on to acrylic because I wanted to work larger. Finally, I started to work digitally mixing together all these experiences.

The way I conceive my work is very intuitive and experimental, but I am aware that I am using all the techniques I have learnt in my training process. When I build my collages in layers, the way I search for balance and harmony or contrast of forms and colours is very “architectural”, so, I think in the end everything adds up. Likewise, the way I relate to the aesthetic problem is totally linked to being a middle-class architect, living in a cosmopolitan city in a global world. My cultural substratum is not very different from a New Yorker or a Londoner, with some touches of tropical culture. I am particularly attracted by vibrant colours.

This multidisciplinary approach is the result of a long working process. I am glad it can be figured out. I have been working hard on it. It is a process of stop and go and come back and go again. I write a lot about my process, I also collect a lot of images and ideas and build from them. I am always making evaluations of my process and taking down notes and trying to have new insights.

I have also been greatly influenced by other artists. I am co-founder of an international network called Urban Dialogues. The idea of

creating the group was to examine the interactions between artists of different cities and cultures, using photography, digital art and video to capture contradictions and analogies of our collective histories. While building the group with the New York artist Amy Bassin, I was definitely taking my work to another level. I started making digital collages in collaboration with other artists of this network. So, my work was greatly influenced by this group.

But then again, I would stop and think, how can my work fit in, how can I work together with them and still be myself. So, I am always trying to figure out how to have my own speech. I guess in the end it is my architectural training, I am always building on top of other things. And then, once I find a track, I can let it flow and I can be intuitive.

As I said before, I started making digital collages influenced by the Art Collaboration Network Urban Dialogues. I started talks with New York City Artist Amy Bassin about art and the public space. This was back in 2009, we were questioning the excessive use of publicity images in the city. As an Architect and Artist, I was very excited about the urban habitat as a place of

celebration. I had the idea of megacities as lively and colourful places, meeting places and a live lab for experimentation of innovation and new ideas. Amy´s way to look at the megacity was more critic and not so colourful. She called life in New York City “the rat race” and saw excessive individualism and feelings of abandonment and isolation in the city life. We both thought that new technologies could help us start new dialogues, create networks to bring together people with similar interests that might unite diversities and similarities.

So, we started to discuss new ways of displaying art and produced collages of street scenes where art replaced advertisements on bus stops and newsstands. Excited by the first results of this collaborative work, we decided to expand the project globally, using social networks to meet and collaborate with other artists from different cities and different cultures. More than half of the world population is already living in urban areas. Our world and our lives are becoming more complex and interdependent. I believe that

we are urban-beings. Cities are a collaborative construction. So, the relation between public sphere and art today, the inner and the outside, is an ongoing process of give and take, we are constantly reaching out for new experiences. Exchanging to transform. We are living immersive experiences all the time, in the internet and in the streets. We are spectators and we are actors as well. Today everybody has a camera at hand and we are all documenting reality all the time, through our different points of view. So,

what I tried to do with the Mother´s Milk series was to mix art and performance, transforming the museum into a stage, to immerse viewers on the artist´s quest.

I like being multi task and working with multiple resources, I enjoy exploring different disciplines and media. I love to open several windows at the same time. Too many! And, generally, I have trouble in getting focused and being more productive. Although I work with art as a process and process takes time, usually I am attracted to mediums which have quick results.

I was first captivated by watercolour because it is so instantaneous, when you get it wrong there is no going back, there is no retouching, there is transforming. A mistake can lead you to a different path, you might end up with surprising results that you did not plan. Then I chose acrylic because it is also a quick medium. It dries out very quickly. I could never work with oil painting. And digital work is very resourceful, it is possible to experiment such a lot. I have had the opportunity to work in a traditional print studio at the Visual Arts School of Parque Lage and experiment with all different printing techniques and although the old manual process is fascinating, it does not attract me at all. I want something I can handle in my small studio at home. I like to work and create out of very basic resources and build up from them. I don´t have sophisticated cameras and computers.