Illustrated by Mollie Ray www.mollieray.co.uk

Designed by Albie Clark at artlinkedinburgh.co.uk

SECOND PRINTING

Although the author and publisher have made every effort to ensure that the information in this book was correct at press time, the author and publisher do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. Some names have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

© 2018 Gail Keating/Mollie Ray. All rights reserved. No reproduction without permission.

Gail’s Paper and Pens - Volume 2: Strategies

Introduction

Communication and Language

The Visual Timetable

Rewards: Who Wants One and Who Needs One?

The Countdown or Count Up Time ... On Our Side

Waiting

Choosing

Question Mark?

Rules and Not Allowed

Paper and Pens

The Mum, The Dad, The Human, The Obsession

Non-confrontational

They Have to Let You In Appendix

Bio/Acknowledgements/About this book

Those with autism and those who relate to them have to deal constantly with the question mark that is the mystery of everyday life. Often, without consciously realising it, we expect autistic people to do things in the same way as we do and this can place obstacles in the way of their understanding of us and perhaps learning from us how to cope better with the stress of daily living.

Both volumes of “Paper and Pens” aim to help all of us who share the lives of those with what is called autism to learn to think differently ourselves so that they can understand us better. Everything in these pages has been lived out in real situations in my life’s work as a teacher: the majority of which was spent with pupils with complex learning difficulties and behaviour which was described as challenging by educational and social work services.

It was one of these pupils around thirty years ago who first taught me the power of paper and pens when communicating with someone who is anxious or stressed or who needs extra time to process spoken information. This technique was to prove extremely useful when communicating with those on the autistic spectrum.

In Volume 1, the vignettes of the characters simply illustrate something significant about each of them: either a single episode or an ongoing characteristic. Together we have found solutions to individual problems and difficulties and also had a lot of fun in the process. In Volume 2, we examine how we neurotypical folk think and act in several everyday life experiences before moving on to explore how those with autism may function in similar situations.

Recent research published in November 2018 from the University of Utah shows that people with autism experience prolonged brain connection times

which, in practical terms, means that their brains are not efficient at rapidly shifting between ideas, thoughts or actions1. The brain connections of people without autism fade quickly but the brains of people with autism can remain connected for as long as twenty seconds.

Over the years a whole range of strategies has been developed to ease communication between those with autism and those who want to relate to them and many readers may be familiar with several of these. Throughout these books we shall discover that paper and pens are invaluable tools for use before, after and alongside these more sophisticated methods. Indeed, several myths have to be set aside if we are to make best use of the official tools.

Learning to think differently is a mutual experience and is definitely not a one size fits all process. Endeavouring to find common ground for meaningful and helpful communication is both a challenging and a fascinating experience and hopefully a rewarding one for both parties. The most important questions for those of us who share in the lives of those with autism are: “What is the individual saying in words or actions?” and “What does he or she need us to say to him or her right here and now?” Our creativity of interpretation and response is given free rein and if, at first, we don’t get it quite right then we keep trying in the knowledge that it is a great privilege to be part of creating a better quality of life for someone by lessening their anxiety, helping them to acquire tools for self management and enabling them to have fun.

November 2018

1Evaluation of Differences in Temporal Synchrony Between Brain Regions in Individuals With Autism and Typical Development

Jace B. King, PhD1,2; Molly B. D. Prigge, PhD3,4; Carolyn K. King, BA1,3; et al Nov 2018

“If only they’d talk to each other.” How often is that said in everyday lives by third parties observing situations? It’s said about partners in relationships and in business. It’s said about parents and children, siblings, colleagues, friends, bosses and workers and even nations. Unfortunately by the time someone expresses the wish “If only they’d talk to each other” some breakdown in communication has already happened with undesirable consequences.

It’s encouraging for our purposes that talking to another person is seen as something that can make a positive difference but it’s not just talking in the sense of words being said one to another. It is much more complex than that. It is about which words are chosen to be said, how they are spoken and what is heard. Sometimes it is not about actual words at all.

Communication involves our whole being. We communicate with our body language and with our written words and the more creative amongst us communicate with their music or art.Therefore no one is excluded from communication as there are so many different forms. Our physical or intellectual ability is by no means the most important element as there is no “one size fits all” in communication and that can be at once our greatest excitement and our greatest challenge.

Paper & Pens

As with most challenges, when they are faced, the reward is great. Communication, communication, communication I would suggest as a mantra for all engaged in the care and development of people with learning disabilities of all kinds.

Before we get too daunted by the thought of communicating with people who are different from ourselves let’s stop and think what an amount of expertise we already possess. How many languages do we speak every day? All of us, even if we insist we only know how to speak English!

Let us ask ourselves if we speak to our partners in the same way as we speak to people at the supermarket checkout. Do we speak to work bosses in the same way as we speak to our family members and what about talking to babies and pets? Then perhaps we have to give a presentation to an audience or negotiate on the phone with someone in a distant call centre.

It is not just in verbal language that we are accomplished. We leave notes on the fridge or dash off an email or text message using the abbreviations that are currently in vogue. Depending on the demands of employment we write reports, legal documents, minutes of meetings; all with their own specialised forms of language. We all acknowledge that we don’t speak to everyone in the same way and so why should it surprise us that our means of communication with those with autism or learning difficulties should be individualised? It is in this individualising of communication that both the challenge and the excitement lie. The challenge is in the reading of the person and

Communication and Language

what they are saying to us and to the world with their whole being so that we can endeavour to reply in words or actions. This can often be difficult and mistake ridden along the way but the excitement comes with the response showing that our attempts at communication are received and understood. Then there is no stopping us once we have achieved the first step in the road to genuinely shared and mutual communication. Further along the road we might reach the stage when communication can be enjoyed for its own sake and not just to give and receive instructions or information. When our communication reaches this stage we can actually have fun. I know. I have had lots of it and I find that really exciting as that is communication shared together but about something outwith ourselves. It is not threatening as it’s not about either of us. It’s not confrontational as there are no demands being made by either party. It’s not functional as there is nothing being requested. It is a lovely spontaneous exchange of words, gestures, symbols, glances, smiles or eye contact showing that there is mutual satisfaction in this particular encounter.

It is generally accepted that consistency of approach is essential for success in all aspects of the care and development of people with autism and learning difficulties. That’s fine as long as the individual is not sacrificed in the cause of standardisation. This is when the method eclipses the person. It is often done in schools and care settings and is done with the best of intentions as it is thought that standardisation lessens confusion for both clients and staff. So spoken words are scripted and photos, typeface and symbols are all in the same format and often in the case of Boardmaker symbols their borders must be the same thickness and there is even discussion about whether their

Paper & Pens

The danger then is that the method becomes the primary focus. Conventional wisdom says it has been proved by research and experience that it works. The method is what our clients need and so that is why we use it. So if individuals do not respond in the expected manner then that is another little failure on their part. That may sound harsh but they will know themselves in their own way that something has been expected of them. They might not know exactly what it was but they will know they have not got it right. Several of these mini failures can contribute to either a loss of confidence or an aggressive rebellion as either way it is not worth trying any more. Communication has broken down and it is up to us non-autistic people to change: to adapt our form of language to suit the individual with whom we are communicating.

This may mean speaking more slowly, using fewer words, allowing time to process what has been said before we add on something else. It may also mean supplementing or even replacing our words with symbols, signs, photos, drawings, actions. Whatever the method our primary aim remains the same in all forms of communication. Our focus is not so much on what we want to say but on the other person and what does he or she need to hear in this particular circumstance or at this point in time. We won’t always get it right first time but as we get more practice at “reading” other people and formulating our appropriate responses the world becomes a much happier and more peaceful place.

Communication and Language corners should be square or rounded.

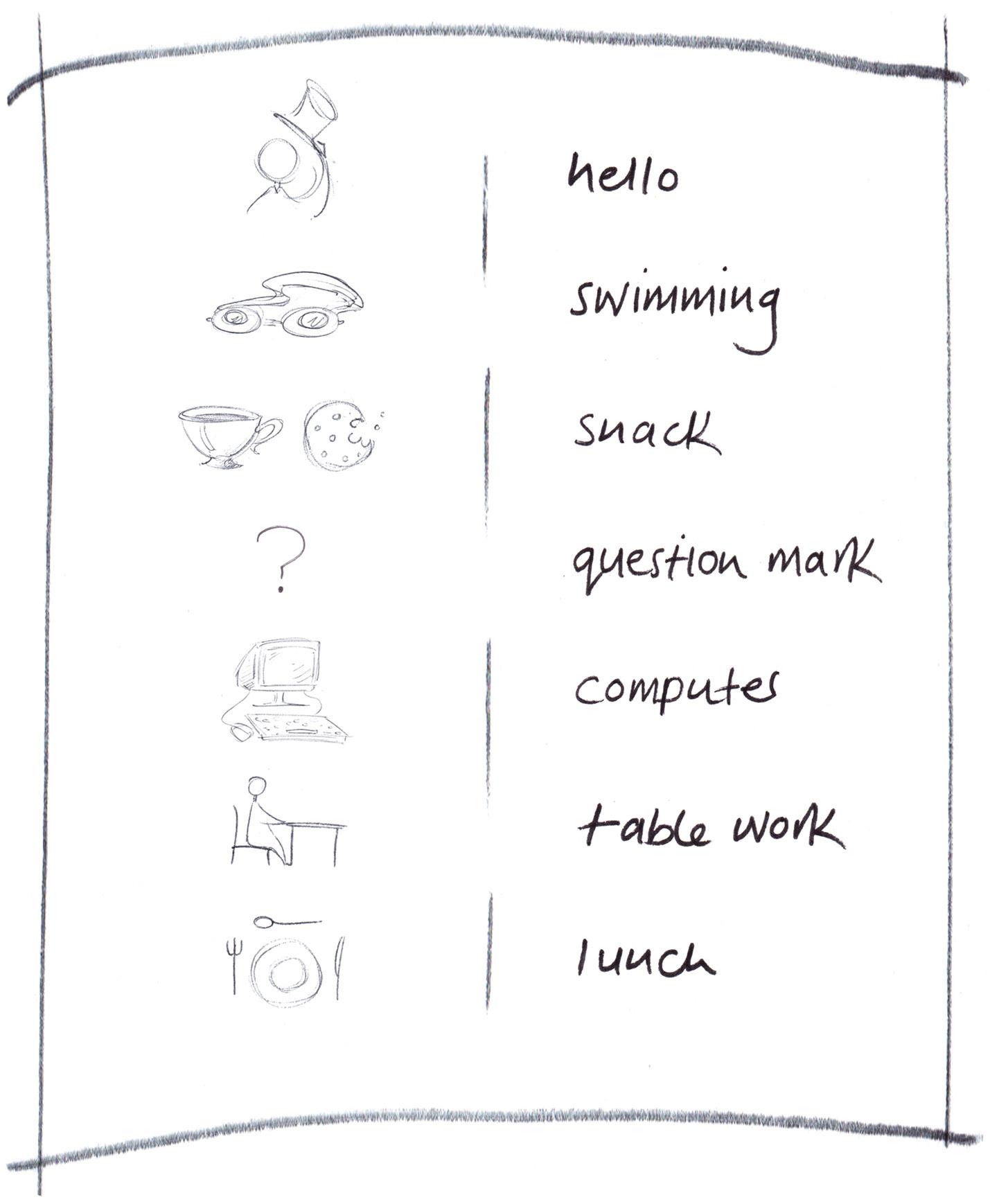

“A visual timetable.” We hear those three words so much in places frequented by people with autism. They are three words that make me a little bit wary when I hear them as sometimes the visual timetable is credited with far too much importance. It’s as if it is endowed with magical powers and it’s often implied that everyone with autism should have one and anyone who can’t read words just needs pictures and then everything will be alright. And then when it’s not alright the responsibility for the failure is laid at the door of the user of the timetable. “Well he knew what was happening. It was on his timetable” or “I showed him the picture but he still didn’t move.” The timetable has its limitations. It is only a single tool in the communication box albeit a very valuable one. Many a computer programme is only as effective as the person who created it as its efficiency depends on the data that has been put into it. It’s the same with the timetable. Sometimes there is too much information and sometimes there is too little but when it is just right it is truly fit for purpose and gives its user the security and focus which frees them up to accomplish so much. Getting it right for the individual needs a bit of thought but that shouldn’t really be a surprise when we think of ourselves and how we all do things differently in the planning of our daily lives. Starting with keeping a record of our own engagements: where we are meant to be, who with and at what time, I find it quite amusing that at the end of a meal in a restaurant with a group of friends someone always asks when we will meet again. Then out come the phone, the pocket calendar, the tablet, the diary or the scrap of paper. Each to their own. Some people

How we cope with changes to our own timetable varies so much too. A last minute change of plan or unexpected happening which has a knock-on effect on the rest of the day’s events can cause anxiety, confusion or anger for some of us whereas others thrive on the break from routine and can take it all in their stride. Whether we are neurotypicals or people somewhere on the spectrum of autism we all know that when we are stressed it is much harder for us to take in and retain information. Some degree of stress is present on so many occasions in the lives of those with autism and so anything that can alleviate the effects of this can only be good. This is when the visual timetable comes into its own as a valuable and useful method of communication especially when it is used on a regular basis to avoid the stress occurring in the first place.

It is generally agreed that there are certain characteristics and patterns of behaviour that are common to many people with autism.

Some of these are:

The Visual Timetable abbreviate every word and others write everything out in full. There is no right or wrong way. Each method is valid for the person who uses it.

They often find it easier to process information given in a visual format. A visual instruction or explanation remains where it is for another look unlike spoken words which can disappear into the air before they can have been processed. This is particularly the case if the person happens to be stressed at the time.

Transitions are often difficult and can often be a time of panic because something is changing and many autistic people are not good at making quick adjustments. Transitions don’t have to be major to cause panic: going out to the car in the rain, moving from the computer to the lunch table and even getting out of bed in the morning all have the potential to leave autistic people hanging in a state of nothingness without direction.

A tendency for obsessive interests and behaviours can provide an individual with security but this can also have the effect of making it much harder for the person to disengage from them.

Difficulty with the concept of time often means that extra help is required with recognising the beginning, middle and end of activities or routines (this is also addressed in the sections on Time ... on Our Side, Waiting, and The Countdown or the Count Up).

Organising their resources, activities or even ideas does not come easily to people with autism and so they appreciate having things broken down into smaller and more manageable steps.

A visual timetable can be helpful for anyone displaying some, all or even just one of the above characteristics. That’s the most important point. It’s not a “one size fits all” strategy. It’s a communication aid and, as is pointed out in the Communication and Language section, none of us communicates with every person we encounter in the same way in the normal course of our everyday lives. We adapt our

Paper & Pens

Sadly I have seen so many occasions when the use of a visual timetable has been a kind of “lip service.” It is used because someone has said it is the right thing to do.

So how can we ensure that the provision of a visual timetable genuinely is the right thing to do and is not just a replica of a conventional timetable but with symbols replacing words?

The first requirement is that we think of the individual, what we want to communicate to him or her and how best to do that bearing in mind

Visual Timetable language to suit the person, place and purpose. So the challenge for us is to make our visual timetable speak different kinds of language too and that means thinking firstly about the message we want to convey and then thinking about the best way to communicate it so that it will be understood. Sometimes there can be a little complication here when communicating with people with autism and that is that we cannot presume that they are seeing what we are seeing when we are both looking at the same object! They are quite likely to focus on some tiny but fascinating detail in a photo or symbol and not see the whole picture as giving them a message. So it’s always worth finding a non-confrontational way of testing out if they can “read the pictures” so that we know we are both talking the same language.

that it is totally acceptable to use different forms of language. Thinking of the individual could include considerations such as:

How quickly they process information and how much can they cope with being given all at once and always bearing in mind that this quantity will decrease with stress.

What is their preferred means of receiving information: spoken, word text, symbols, Signalong, drawings or a combination of two or more of these. Also bear in mind that this might need to slow down, change or be supplemented in a stressful situation.

What causes them most anxiety?

Is it not knowing what is next?

Is it panicking because they will be parted from the security blanket of their obsessive interests or behaviours?

Is it not understanding the concept of time?

Is it because they have to move from one place or activity to another? Is it seeing some unpleasant activity featured on the timetable?

So bearing all these possibilities in mind, plus any that are not mentioned, we now ask what information we want to convey. What is going to be the most helpful: the most fit for purpose?

When we think of what information we want to give in the formulation of a visual timetable the most important consideration is HOW we give it. And this “how” is much more than just pictures, words, symbols or photos. The information we give on the timetable is more

Gail’s Paper & Pens

than just telling what is to happen today: a sequence of actions or events. This may be sufficient on a “good” day but today is a new day and what was good yesterday might not be the same today. A useful visual timetable can help the person to successfully accomplish these actions or participate in the events by freeing them from the anxiety which so often is a barrier to success.

So how do we do this? Let’s look at some of the previously mentioned individual considerations. For someone who doesn’t understand the concept of time there are various levels of timetable format.

The basic Now and Next strip

Now Next and After: introducing a third space

This strip shows what has already been accomplished as Finished or Done. For the following strip the last symbol (the “Next”) from the previous card becomes the first (“Finished / Done”) on the strip so that the person can experience a continuity of time.

If and when this basic level of sequencing is understood then the level of complexity can be adjusted to suit the individual and the current situation that is to be timetabled.

A further stage could be using familiar times as bookends for the timetable e.g. starting with breakfast or shower and finishing with snack or lunch depending on the individual’s ability or number of activities to be done.

If the person is familiar with signifiers such as a timer or clock being used to indicate the passage of time then that can be put on the timetable. “We’re going to do this until the timer says “Stop” accompanied by the timer symbol. Or “We do this until the clock says ... ” accompanied by the clock face picture showing the time to be matched with the clock or, alternatively, the real clock with the finish time shown on it by a felt pen mark or piece of Blutack.

For those who need to be parted from their object of obsession in order to focus on something else the most important piece of information to convey on a timetable is when they will either get their object back and/or have time to engage in their obsessive interests or behaviour. So it goes on the timetable in either picture, symbol or word for whatever it is the person recognises it as, or for me as I most often make up the timetable in the presence of the individual, a drawing. This drawing of the timetable with the individual watching is one of my favourite strategies. It isn’t necessary to be a great artist as often I am copying a Boardmaker symbol. If we don’t have an appropriate symbol or I am conveying an action then it’s pure basic minimal line drawing or stick figures. Another advantage of drawing is that a pen and paper can be brought into use anywhere at a moment’s notice whereas the appropriate symbol might not always be to hand. And usually, and very importantly for the watcher, I put the obsession or whatever is the currently desired activity or object on first at the bottom of the page. Having this reassurance that the desired object is definitely on

the programme often ensures that the client is more tolerant of what is going to be asked beforehand. Sometimes the desired object or activity is placed second if I am placing something already accomplished at the top to be ticked off immediately as that signifies success at having done something to be ticked off already. Then there is hope for the future as there is what is wanted at the bottom. “It’s on my programme so it must be true!” Hopefully then what goes in the middle: the non negotiables will be better accepted.

When establishing this principle of “task first ... reward later” it may be necessary to include multiple reward breaks in the timetable as when introducing this principle the time on “reward” may often outweigh the time on task. But we consistently monitor this and gradually increase the time on task whilst lessening the breaks in between.

Brian shows a good example of this and was able to demonstrate that this was a strategy which he found helpful and could also be transferred into other situations. One day he came into school more agitated than usual as he thought it was his final day before leaving our school as his sisters’ school finished that day whereas we had another week to go. Standing at the top of the steps, eyes cast down and furiously working his knuckles as he did when stressed, he suddenly declared: “I’ll need hundreds of swings today.” “Yes, that’s good thinking.” I

Paper & Pens

replied. “Right, you put it on my programme while I go on the swing,” he said and that is exactly what we did. Back on track because we had backtracked to an old familiar regime he showed us that he really owned that strategy and also recognised when it had served its purpose as later in the morning he crossed off the extra swings he no longer needed as he had other more interesting things to do and knew that he was able to do them.

If the individual does not have a regular favoured activity then “choose time” can take its place on the timetable. At this time it is acceptable for them to do nothing if that is their choice but it is advisable to have a rule here that it is to be “by myself” and not involving others.

“by myself”

“with . . . . . . . . . name / photo” and “group” are also useful inclusions on the timetable for those who are attention seekers or find close proximity to adults difficult.

We all like rewards but do we all need them? It depends on what you mean by a reward.

If you are in paid employment do you consider your salary as a reward for the work you do? Probably not, as you consider it your right to receive a just wage for your labour and the chances are you couldn’t afford to live without it. You couldn’t afford to work for nothing. Then when you have got your salary what do you do with it? If there’s anything left after you have paid all the bills and seen to all the things that are necessary for living a reasonable kind of daily life then maybe you could go on holiday or change your car, upgrade your technology, go out for a meal, buy flowers for the house or get a latte on your way to work every day or ... the list is endless because we are all so different. We don’t need any of that list of things I’ve mentioned but we may think they add something to our lives. So they could be considered a kind of reward as they’re extras: something we give ourselves because we tell ourselves we have earned it.

Not all rewards cost in terms of money. An hour or two to yourself to do what you like may be a reward to a busy person and so might be the chance to visit a beautiful place. On a more mundane and personal level I work best and fastest when there is a time deadline hanging over me. So if there is some household task to be done that I’m not really keen on doing then I sometimes create a deadline by setting my kitchen timer to see if I can finish the task in the allotted time. Then

I can watch the programme or have some coffee and read the paper: ordinary things that I might do anyway but using them as a “carrot” means that at least I have got the ironing done or the kitchen cleaned. Definitely more of a motivator than a reward.

Simple, but it works! It works for me but it certainly wouldn’t work for everyone as we are all so different. We like and dislike so many different things and we are all motivated by so many different factors. And furthermore, we don’t always favour the same thing every time ourselves. We have a whole bank of “rewards” to choose from according to our circumstances or our feelings at the time. If we were to be limited to the same reward all the time and had no control over it I think it might pretty soon lose its effect as a motivator.

So why should it be different for people with learning difficulties or autism? It shouldn’t, but in reality it is quite often different as we start from the wrong place. We look for something to use as a reward / motivator with an individual but we look for it ahead of time so that it’s all ready to roll when we want to start learning a skill, doing a task or engaging in an activity and then we are surprised when he or she is not interested in cooperating even though we know he likes whatever it is we have decided upon to dangle as the carrot to get the task done.

Rewards: Who Wants One and Who Needs One?

“We know he likes it” because we have gathered all the information; we’ve observed him; we’ve asked everyone who knows him; we’ve completed all the charts and, if he is able to tell us, we have probably asked him. But we haven’t matched the “reward” to the task for the person and so there may be a missing link here. Often the reward or most successful motivator for the person is something that we might not think of as a reward at all. Also if the task or whatever it is to be done is a cause of anxiety for the person then just to achieve it is its own reward and to insist on the “reward” being accepted is often a step too far. This is when the drink gets thrown or the favourite DVD gets smashed. In an already highly charged situation we have added in something else that needs to be processed and that is just a step too far. A simple word of praise or a thumbs up may have been sufficient and / or maybe some of what I call “autistic time” in which the person gets to do their own thing, whatever it is and whether or not it seems pointless to us.

Often the best and most motivating “rewards” are those that have been decided on the spur of the moment and spring from a direct relationship between the individual and the situation. If the time difference between the agreement or promise of the reward and its actual reception is fairly brief a verbal agreement may be enough. If it is going to be longer or the person is going to need more persuasion it is desirable to record it in a visual format: text, symbol or picture so that the person is motivated to keep going as the desired end is literally in sight.

Gold stars, golden time, reward charts, all the conventional social based reward systems are often too abstract for those with autism and so are rewards which are too far into the future without being broken down into smaller chunks of time with tangible indicators of achievement along the way. However a person with autism will often go to great lengths to obtain something which appears to be for their own satisfaction. This is often something in which most of us would not be the slightest bit interested. We had a boy in our school who used to get very excited about going home after he had had a good day because, and he could hardly get the words out at the thought of it, “I’ll get to hold the box.” The box he was so keen to hold was a case for one of his Dad’s DVDs. Whether or not it was empty we shall never know as that seemed to be irrelevant to its motivational value. The contents didn’t have to be watched. It was sufficient to hold the box.

So rewards or motivators? Are they the same if they both get the job done and achieve the desired end? I think I prefer motivator as ideally we are working towards it not being needed: that achieving the task whatever it is has its own inherent satisfaction. That’s a great day when that happens!

Rewards: Who Wants One and Who Needs One?

When I was working in a school my staff team used to tease me about confusing people about driveways, lanes, corridors, anywhere that had a top and a bottom. The main destination or the furthest away point to me had always been the top and so I would say we were going to the house at the top of the drive or the classroom at the top end of the corridor and thought everyone else said the same until one day on an excursion to a local country park it came to light that they didn’t. This park had two car parks: one just inside the entrance gate and one at the other end of the road adjacent to the big house and adventure play area.

Evidently one of our staff team had already briefed the bus driver that we were going to the car park at the bottom of the entrance road but as we approached he checked with me “The bottom car park?” “No, the top one,” I replied and so he duly pulled into the one nearest to the gate. “No, it’s the other one we’re going to” I said, “So that we’re near the adventure park.” “Yes, that’s what I was told before,” said the driver “But I thought you’d changed your mind.” Then it turned out that what I termed the top car park because you went up the road to it, everyone else referred to as the bottom car park because you went down the road to reach it.

Same car park, same road, but it may as well have been poles apart and in that particular instance it didn’t matter. However, it could have been very different if we had needed assistance in a hurry and my phone call

had sent our aid to the wrong place! I am saying “my” phone call as it seemed that I was the only one who was out of step in this instance, but who is to say who is right? Is there a rule about when to say “up” or “down,” “top” or “bottom?” There may well be but I haven’t researched it yet.

So “count down” or “count up”? This has definite confusion potential. You count up to ten but counting up to ten can be used as a count down strategy to signify time to stop or time to start something. Counting down doesn’t always mean counting from ten down to zero as if every occasion is a space launch.

I use “counting down” as a strategy quite frequently with anyone I whom I know has a minimal understanding of the function of number. However, just to extend the confusion, I am usually counting up as that is how people learn to count and process that the higher numbers mean more objects or longer time.

The phrase that I use to signify a countdown is just “Let’s do ten” or “Let’s do three” depending on the person’s ability and the function of the countdown in the particular situation. One young man with whom I have worked since he was ten years old likes to initiate a pretend chase with the words: “Gail cannae catch me.” This goes back to his earliest years when his autism compounded with the abusive

The Count Down or Count Up

Gail’s Paper & Pens and unstable situation in which he had previously lived meant that he could not be touched at all by anyone without an aggressive reaction. I had set out to build up his acceptance of touch as this was going to be necessary if any medical or dental treatment was to be needed and also if we had to use physical intervention for his own safety and the safety of others. This was a long process as there was much to be undone. I began by a tig type game in the school hall so that the initial single touches were hardly felt as we were constantly on the move. The next stage was my saying: ”I’m going to catch you for two” and so the touch was a tiny bit longer as it was held for a quick count of two followed by an immediate move away so that I was creating a distance between us without his having to react to force me away. When “two” was accepted and established successfully then: “I’m going to catch you for three” and so on eventually reaching ten. By this time he would often do a very short run and then stand still and wait to be caught with his back towards me so that ten meant either my holding his upper arms close to his body indicated by: “I’m going to squash you for ten” or ten quick massage-type strokes on his upper back. The holding of the upper arms close to the body was a deliberate strategy to ensure success in case of a sudden panic as the arms were not able to grab or hit but this “pretend squashing” was viewed by him as a game which gave him a degree of confidence in being acceptably physically close to someone. These catches were always followed by an instant and somewhat exaggerated moving to the other side of the room on my part. This reinforced the message in his terms that “If I tolerate something for the stated amount of time it will stop without my having to hurt

anyone to stop it.” This was the beginning of learning to trust other people and lots of years later and in different living situations he still initiates this original “chase” situation in order to show his confidence and willingness to engage in further activity. I always check out this level of confidence and when he says: “Gail cannae catch me.” I ask before moving on: “Is it for three, six or ten?” The reply is usually ten but if I think that the situation is not quite right and he is more edgy or anxious than usual then I make the decision: “I’ll catch you for three.” This is always accepted as I think that, although he wants to demonstrate his trust he also has the insight to know he might not manage it successfully and he is pleased that I am not going to allow him to lose his own control.

Counting also plays a part in time management and especially in the micro management of time that is a very useful strategy for those with autism. Counting can be like a portable timer. It can be used anywhere to signal the beginning or end of something. Unlike a mechanical timer it can be flexible and adapt more easily to a particular situation. Ensuring success can sometimes just be a matter of counting more slowly or more quickly depending on the circumstances. Here are some examples of this flexibility:

Sometimes it can take autistic people longer to process an instruction if they are really engrossed in what they are doing. If they are doing their own thing, having their “autistic time” and you get their attention to tell them it is time to stop and move on they are more than likely to turn back to their own activity as if they haven’t heard you. They

probably did hear you but need a bit of processing time. If you have said “We’ll count to ten,” and they suddenly start to pack up their stuff then a quick count will ensure you both finish at the same time. If they don’t start to pack up immediately a very slow count keeps them on track. It reminds them that they are meant to be doing something and hopefully they manage to get it together to beat the deadline. Success all round.

If someone finds a particular activity so pleasant that it is in danger of becoming an obsession then counting can put a gentle limit on it. In our sessions in our snoezelen (multi sensory) room one boy used to love to get his back and lower legs stroked with a light massage effleurage type movement. He requested his favourite input by turning on his front or presenting his leg with trousers rolled up to the knee and signing and saying “please” and taking a staff hand if we appeared not to get the message. This was fine at first as it was appropriate that each person had an individually preferred sensory activity in snoezelen. But eventually he began to get very cross when he seemed to consider he hadn’t got enough value from his request. He wanted more. In fact, he just didn’t want us to stop. He was a big boy and arms, legs and mouth could all be quickly deployed in expressing extreme agitation. He was a basic PECS user and was just beginning to verbalise single words, some of which were one ... two ... three. As he was enthusiastic about counting and pleased with the praise he received for this a countdown seemed an obvious strategy to use in putting a limit on the possible future obsession.

Gail’s Paper & Pens

So, “We’ll do three then stop.” This was a v-e-r-y slow three matched by the speed of the hand. He was fascinated by the number counting. It was language he recognised but in a different place and he decided himself to join in the count. As his counting improved we could do more numbers and count faster. Then I introduced a count for “waiting” for his next turn. By the time I was counting up to thirty he was joining in to help with the count and had forgotten he was ever so obsessed.

Counting is also a useful tool for self-calming. Someone who is getting worked up about having to do something that makes them anxious can be told to “Stop. Let’s count,” plus, “Then we’ll talk about it,” or whatever strategy will be most helpful for the particular individual. This is really good when, having learned from experience, they adopt this strategy for themselves and the firmly spoken “Stop” is enough to remind them to “Slow down. Cool it.”

One day one of our boys was in the toilet when his mother unexpectedly arrived to collect him. He heard her voice, came bursting out of the toilet and, as she was talking to us and not moving out that very second, he began to jump up and down and make a lot of protesting noise. The next stage would have been to aim the flailing arms in Mum’s direction and we definitely did not want that to become a learned behaviour that makes someone move on demand. So “Ollie. Stop.” I said quite firmly. “One, two, three ... ” Instantly he stood still and began to join in the count. Then we were back on track and able to tell him he was “waiting” and we would “count some more and Mum

The Count Down or Count Up

will get her car keys.”

Mum was amazed at the instant calming and said she would most definitely implement that strategy at home.

See also Time ... On Our Side (pp46 - 53) and Waiting (pp56 - 61).

Time is only usually a problem to us when we have either too little or too much of it. Either can be stressful. Too little time when we have a deadline to meet can cause us to panic at the consequences of perhaps not being back home in time for children returning from school or to pick up an elderly relative at the station. It can even cause accidents as we cut corners and get careless in our haste or at the very least get annoyed with anyone who unwittingly holds us back still more. Too much time if we are waiting for something to happen can cause stress too if we are bored or stuck somewhere that we really don’t want to be or, perhaps worse, with people with whom we want to spend as little time as possible. Fortunately we have lots of run of the mill ordinary time in between these two extremes when we just go about our business without giving time a second thought.

Not so for people with autism. Time, in all its contexts, causes major difficulties for them. But think of time’s qualities of consistency and utmost predictability and how it threads its way through all the activities of everyday life and it has all the ingredients to become an extremely useful strategy.

So how can time become a helpful strategy? Let’s start at the beginning as it is generally recognised as being a very good place to start. Well, perhaps not for a lot of people with autism as they are often much more interested in the end. “How long can I keep doing this when it’s something I like?” “How long do I have to stay here? How long

Gail’s Paper & Pens

do I have to keep doing this when it’s something I don’t like?” are the probable questions in their minds and because they are not as skilled at managing time as the rest of us their answers are not likely to be the same as ours. They might refuse to stop doing something they like when it is time to move on. If it is something they don’t like they might just walk out or, if walking out is not physically possible, all objects connected with the distasteful activity may get scattered to the floor. If another person is nearby and forming an obstacle to this avoidance then they might be in line for a kick, a hit or a thrown object.

Remember I have just said, “Because they are not as skilled at managing time as the rest of us.” That needs some clarification.

I am extremely fortunate to have spent my working life in a job in which I did not have to watch the clock because I was bored or I wanted my working day to come an end. The only time I can remember clock watching was when doing a student job on the Christmas post. The time flew by when I was out delivering but I think I turned my head every slow minute to check the clock for finishing time when back in the office rooted to the spot doing the mail sorting. At least it

confirmed for me that I was definitely better suited to a job involving lively people and plenty of movement. This is where there is difficulty for people on the autism spectrum. They don’t do imagination and social consequences easily and so to project themselves into the future and think “Well, I only have to do this job for a little while and then I can get back to working with people again,” would not be much of an incentive for them to keep going for a while longer. I suspect it would be more problematic for them to have to stop doing a routine and predictable task in order to move on to a situation in which people chatter constantly and do not stay where you put them.

That is why when helping them to get time on their side I often start at the end. That means placing what I call their “autistic time” on their programme first. I am able to do that because I often make up their programme within their sight and / or hearing as on most occasions I am drawing it and therefore able to be super flexible. Modifications are possible on grow-before-your-eyes hand drawings that are not possible with laminated symbols. So if someone’s particular motivator or “autistic time” or self-chosen activity is computer, jigsaw, book, tumbling pieces of card or even just time to “choose” then put it at the bottom of the page or the end of the line depending on the schedule layout.

Then how are we going to achieve it? We fill in the required activities either backward chaining until we reach NOW: the beginning or if something of significance, however simple, has been already achieved then that goes on the top of the programme: “That’s great. You’ve had

Gail’s Paper & Pens

a shower / cleaned your teeth / said Hello / got your stuff ready ... so we can tick that off ... and NEXT ...” Then we work downwards in setting up the programme until we reach the desired FINISH. END. TIME TO STOP.

This is a multi purpose method of scheduling required activities. Required activities can be self care tasks such as showering, changing clothes, washing hands, having a shave or hair cut. These are mainly non-negotiable in the cause of health and wellbeing. Also required activities could be school activities, learning sessions, community based or household tasks. The schedule user can see that there is an end and what has to happen step by step from beginning to end and hopefully the end is sufficiently motivating to encourage a beginning! The assembling / drawing of the schedule allows time for the user to process the different stages and is not as overwhelming as if it is presented all at once. It also enables the addition of extra “clues” such as numbers or key words to aid understanding. There is also another advantage for the attentive visual learners inasmuch as the programme takes shape before their eyes and they can see how each component is drawn and can replicate it themselves to aid their own expressive communication, usually to their advantage. One pupil of mine grew adept at drawing computer and decided to attempt to beat the system by crossing out the “work” symbol and drawing computer in its place. When I entered the room and returned the programme to its original format he quickly reversed it again. After a combined total of twenty moves between us the work finally got done; with the computer after of course. This was the kind of understanding and ownership of the

programme that I really liked to see.

Tools for Time

Blu Tack

White Tack or similar

Washable felt pen

Clock faces: drawn impromptu or pre-copied templates

Timers preferably to fit in a pocket: visual and / or sound

Mini whiteboard or pen and paper

“Please wait” symbol

What we want to do is to give people a visual and / or sound representation of when a certain specified period of time comes to an end. That’s the first step in which they begin to associate the noise alert of a timer or the matching of time on the clock with the stopping or moving on from their current activity. They have to get this message first before the more sophisticated one of being able to cope with the fact that time passes at its own pace and cannot be hurried. Sometimes we pretend that we can hurry it on but more about that later.

As with all teaching and learning we begin with what they are already good at and so we may possibly start with the regular activities about which there is not a problem about stopping and moving on. Depending on age or ability to understand, these activities could be

Gail’s Paper & Pens

getting dressed, teeth cleaning, having meals, completing a task which is to be followed by own choice or something which always happens at the same time such as home time from school or centre. The given signal is also dependent on understanding. It could be the ring of a timer, the matching of the position of the hands on a paper clock face to a permanent wall clock or a written time to match to the actual time on a clock particularly if a digital clock is being used. “So that’s getting dressed / teeth cleaning / lunchtime / writing etc ... finished. Next it is time for computer / car / choosing / coffee ... whatever follows on the schedule.”

Establishing that this signal is a warning that something is going to change is the foundation on which more complex programming can then be built. However, because this stage is so essential it is important to get it right. Imagine if you are all geared up for something to happen at a certain time and then it doesn’t. Depending on the consequences you can feel angry, disappointed, anxious, bored, upset, confused: all of which test an autistic person’s coping skills to the limit, but we shall speak more about that in the sections on “Waiting” and “Question Mark.” Because of the importance of consistency when teaching the link between the signal and something changing we can manipulate time a little bit for our own purposes. If we become aware that there is going to be a slight delay we can surreptitiously push back the timer or the clock hands to give us a bit more time. The delay could be something like a person or a room not being ready for us or transport not arriving in time or even someone taking too long in a bathroom when we are programmed to go there.

Once we have established that we have a means of indicating ends and transitions we can become more adventurous and use these techniques in different places and at different times. That is when the mini whiteboard, the blutack, the pen and paper and the washable felt tip all come into use. If the time to finish is within the next hour the blutack or washable felt pen can be used to make a mark on the clock face to indicate that finishing time is when the hands reach the mark. The whiteboard or paper can have symbols stuck or clock and activity drawn to indicate what is happening next. Sometimes a single programmed activity may need to be broken down into its component parts if it is too long for the person to tolerate as a whole; e.g. within a music session there could be singing, listening, playing an instrument, using a computer and these can all be ticked off as the session moves towards its final finishing time. People who are able to tell the time can have their times written in numbers or words without the use of clock faces on their schedule but always with the acknowledgement that sometimes when people are stressed their more sophisticated skills are harder to access.

See opposite for time tool sample cards.

It’s interesting to watch people waiting as they do it in so many different ways. But then that is not really surprising as there are so many different places in which to wait, so many things to wait for and so many varying lengths of time to spend in waiting; all of which have a bearing on how we wait.

Traffic lights only require a short wait so some drivers just stare fixedly straight ahead and some yawn, stretch or pick a nose. Others try to cram in as much as they possibly can: put on the mascara or lipstick, eat a sandwich, check the phone. But the ones I find scariest are the scowling finger drummers or the drivers of the cars that rock backwards and forwards as the foot is on the clutch ready to roar away the split second the amber light disappears.

Waiting rooms are unfortunately often associated with something that might not be pleasant: dentists, doctors, hospitals, law courts. They often have fish tanks, magazines or TVs with muted volume to lower the anxiety levels of those who wait though often these well intentioned distractions are superceded by people’s own personal screens. Airports and some train stations call these places lounges which implies “make yourself at home as you may be here a long time.” Then there is the standing up waiting: the bus queue, the fast food, the Boxing Day sales, the blockbuster exhibitions.

For us neurotypical people waiting is just so much part of our lives

that we don’t realise we are doing it unless it really brings us to a full stop for a considerable amount of time like an unexpected incident on the motorway five miles ahead of us or being left on hold on the phone with a continual loop of supposedly soothing music. Waiting is an extremely useful strategy to learn but as adults with all our years of practice most of us do not remember how we learned it. It wasn’t one of our school subjects. It was just learned from experience.

“You’ll have to wait for your birthday.”

“Wait and ask Dad when he comes home.”

“Don’t eat that just now. Wait till lunchtime.”

“Don’t push in. Wait your turn.”

Waiting was just something that was not immediate. It was postponed. Waiting was the time in between the present moment and when it would be time for whatever it was we were waiting for to happen. Because we know we are waiting for something or someone we can organise ourselves accordingly to fill that gap of time. We can make adjustments or take alternative courses of action if there are delays or changes in whatever it is that we are awaiting. We can do this because we can look into the future and we have the ability to imagine: to make a picture in our minds of who or what is going to be at the end of our period of waiting.

People with autism often do not have this natural ability. For an autistic person waiting is often not just a minor annoyance. It can be a cause of major stress and anxiety and so the skill of waiting is not likely to

be acquired spontaneously. It needs to be taught and can significantly increase the quality of a person’s life when it is successfully learned.

When we stop and think of waiting as a period of time in its own right we realise how many times we experience it in the ordinary routine of daily life without being aware of it. Then we realise that it is often the shortest and most common waiting times that can cause most distress for those with autism. That is why I teach “waiting” as a portable skill which can be transferred into all sorts of everyday situations. It’s a form of time management and the resources and techniques which are detailed in the sections on “Time” and “Question Mark” can also be used to assist in the acquisition of the skill of “waiting.” We can be much more flexible and be far less anxious if we know how to wait as no matter how skilled parents and staff are at anticipation and monitoring of environments nothing in daily life can be guaranteed to be entirely predictable. Transport can be early or late, as can meals. Shops can have big queues. Service in cafes can be slow. Expected people can be delayed. Rooms can be left in a mess by previous occupants and have to be tidied.

“We have to wait,” but what does that mean to someone who can hardly concentrate because he has been ready to go home for ages and there is no sign of a vehicle or a person to enable this? Or to someone

Gail’s Paper & Pens

sitting at a café table with cutlery and napkins at the ready but no sign of any food or drink. What is happening? All the ingredients for a meltdown are assembled. So what can we do? Well, it is too late to start when the transport or the food is delayed or the traffic lights are not changing quickly enough. The learning and teaching has to be done beforehand in a non-threatening environment when waiting is not necessary.

We need a tangible signifier of waiting as a specific activity so that we make it into something positive that can be ticked off on a schedule just the same as teeth cleaning or lunchtime. Just as with other activities the signifier can be a symbol or text which then becomes associated as indicating that the particular activity is to take place. I like to use the

Boardmaker red “stop hand” alongside the “hands winding back: wait” symbol and the text “please wait.”

When first teaching the strategy it is better to start with a fairly big symbol: approximately 10 x 10cm is a good size. It is also good to teach “waiting” just before something pleasurable is to happen and even better if it follows on the successful completion of a task. “Waiting” is put on the schedule after the task but before the “reward.” This is when the big “wait” symbol is put in full view and the countdown begins. According to the person’s ability level or particular interest various methods of showing the passage of time can be used:

clocks, sand timers, wind up timers, tapping on the table, verbal countdowns.

At first the waiting might only be for a slow count of three to establish that waiting is an activity in itself that has an end like other activities and is followed by moving on to something else. As the waiting time increases it may be advantageous to remind the person of what we are doing: “We’re waiting” or “We’re waiting for ... ” or just simply silently pointing to the “wait” symbol.

Again, as usual, once the specified time comes to an end that’s it. Don’t be tempted to wait longer if all is calm as, at this stage of learning, that could cause a significant setback.

Once the concept of waiting as a space of time has been established we can introduce another strategy to cope with the kind of uncertainty of waiting that might occur when we have no control over the situation. If there is an element of uncertainty about the timing of the next item on the programme, e.g. if in a café or at home or school waiting for a food item to be ready to eat, then the person who is going to be appearing with the food can be the end signifier. So, “We’re waiting for ...” (person’s name and maybe photo if available) and make sure he or she knows not to appear too early when this technique is in its early stages of learning!

Hint: It is really handy to get the learner accustomed to verbal countdowns as they can be used as instant calmers in unpredictable

Gail’s Paper & Pens

situations when timers etc may not be to hand. If the person has an understanding of larger numbers we can count up to around thirty but with practice even a s-l-o-w count of three can last a long time. For PECs users a “please wait” symbol can be kept ready in the PECs book in case their request cannot be fulfilled immediately. This buys you a bit of time to think of an explanation or the next move.

“Waiting” along with “Question mark” are two extremely valuable coping strategies for people with autism or anxiety to acquire. The ability to be flexible opens up so many more opportunities and really does enhance the quality of life for everyone.

“What a great choice!” To hear that remark is not always a good thing. For any friends accompanying me in a restaurant it means a long wait as I am not good with lots of choice in food. That is because I am fortunate enough to be able to eat all categories of food without any adverse effects and to actually like them. Also I am up for trying dishes I haven’t had before. Therefore it is far more difficult for me to eliminate items and so narrow down the extensive choice to something more manageable and while I am still combining ingredients in my mind and making pictures of how the untried dishes might taste everyone else is well past being ready to order. We have a strategy. “Just go ahead,” I say, and I only make the final decision when everyone’s order has been taken and the server’s finger is lifted ready to record my choice. Sometimes I wonder if I should just stick a pin in the menu.

Now that’s OK on a relaxed occasion like having a meal with friends but there are other situations in life when too much choice is not fun. A necessity such as buying lightbulbs is definitely not fun to me. I detest being confronted with shelves upon shelves filled with tightly packed little boxes all with lots of figures to be decoded in order to end up with an item which is a) going to fit in the socket b) not scorch the lampshade c) not burn your head when you stand underneath it d) not contribute to the destruction of the planet and e) give enough light for you to see what you want to see.

Choosing when there is too much choice is complex and often difficult

and we need to develop strategies of our own to narrow down the choice and make it more manageable. Often the situation in which we are choosing plays a big part in our choice. At work or in a family setting we are often choosing on behalf of other people and then we bring a different set of judgements into play than if we were just choosing something for ourselves. Sometimes this is easier as we have clearer guidelines as to what and how we choose. Things like cost, staffing levels, dietary requirements, available time, abilities and interests all place necessary and appropriate limits on our choice. In these circumstances we have to be able to try and decide what will be the best choice for the other person: to put ourselves in someone else’s place. That social skill does not come naturally to someone with autism.

Even choosing for ourselves involves a lot of thoughtful decision making. Do we go for the healthy food or for what we really fancy even though it is red-lighted for fat and sugar? Low cost and looks good for now or expensive but will last us a lot longer? Useful and utilitarian or frivolous and fun? Can we defer gratification or do we need immediate satisfaction and so need to take whatever is right here just now? Go for a walk or watch the TV? These types of choices all need us to have an understanding of time and future: again something which those with autism often find difficult.

To make selecting easier when faced with a sizeable number of choices we often work backwards and eliminate some of the less desirable

Paper & Pens items or quickly sort them into categories in our heads. To do this we need to have a knowledge of what the choices are and to be able to imagine them in order to put them in the right box. Imagination isn’t often a major strength for someone with autism.

Choosing when there are only two choices can be just as difficult if you have no personal knowledge or experience of one of the items and worse still if you are uncertain about both of them. Yet this is so often what people with autism are asked to do: to make an uninformed choice. We glibly ask them to choose a destination, a food item, a colour for new clothing, or a DVD to watch without making sure they know what we are talking about. Seaside, beach, the harbour, the boats, the sea: all these words can signify the same place and we can make adjustments in our mind by getting clues from the context in which they are used as that often gives us additional information. But someone with autism who is already anxious about an impending outing is not going to be able to do that if the word they hear does not immediately hold any connections for them. In that case it is likely that they will choose the play park as that was the other destination choice on offer and they were familiar with the words “play” and “park.” A possible consequence is that they will have missed out on walking on sand or splashing in pools which are sensory experiences that they really enjoy. Another possibility is that as the coats were on, the keys were in hand and the transport was outside they felt pressurised into making a choice to escape from the immediate anxious situation and so repeated the last word that was spoken. Then on arrival at the destination they are reluctant to exit the vehicle as they didn’t really

want to go where they have ended up. “Oh, but you said you wanted to come here. You chose the play park,” is so often the response to this lack of movement.

Food is a difficult area for choice. It’s fine when the choices are there before your eyes. It’s not easy in a hospital, school or care setting in which a menu has to be completed ahead of time. How can we be sure of a dish when there is no clue in its name? Mince, potatoes and carrots may be a much loved dinner but when they are put together and labelled shepherd’s pie it’s a totally different proposition. Even dishes that are thought to be familiar can turn out to be different as one of my former pupils clearly illustrated. He had been used to making stovies himself when at school and so, when in a hospital setting, had chosen stovies immediately when presented with a menu choice. When I visited he told me he had not eaten his dinner which had been stovies.

“But you like stovies,” I replied. “The chef got it wrong,” he said. At school we made stovies with sausages. The hospital used corned beef. In that case no harm done as he had reasoned for himself “the chef got it wrong,” but I have also experienced occasions when the “wrong” or unexpected food has been served up and, in the anxiety of the moment, it has been sent flying through the air in an inability to cope.

Now someone with autism only needs to have had a few experiences similar to those I have just illustrated and the words “choose” and “choice” take on negative connotations because of past failures. “Well, you chose that, didn’t you? That was your choice.”

There is also another kind of choosing we do all the time in everyday life which is not really a choice. It is more like a game we play which is governed by social rules and demonstrates our awareness of and consideration for other people. Things like not taking the largest portion of something if you are unfortunate enough to be first to be offered the plate. Not taking the last chocolate and forgoing the last portion of lasagne when we know it happens to be a big favourite of the person behind us in the queue. Giving up our seat on the bus when, although we have paid our money the same as everybody else, we are aware of someone who is finding it difficult to stand. These are all occasions when we choose to act as we do, albeit reluctantly sometimes, but it could be said that in the name of a civilised society we have no choice.

So it seems that choice for all of us is not as simple as it first appears and too much choice can actually be a cause of stress as opposed to the liberating force it is so often reputed to be.

Choosing is so much part of our daily lives. It is so automatic that we do it without realising that we are actually using the quite sophisticated skill of “choice.” If we recognise it as a skill then we accept that it can be learned and taught. In common with the teaching of all skills it is most successful when its learning can be transferred into all kinds of different situations. Learning and teaching how to choose. Our daily range of choices is so extensive and starts as soon as our

day begins with what to wear, what to have for breakfast, what music to play and so on right through to what time to go to bed. For me, choosing fits into the same category of intangibles: things that can’t be definite such as “waiting” or “question mark.” We have to teach and learn a core strategy that we can take with us anywhere and at all times. As with all skill teaching we establish what is already known, even if the persons themselves don’t yet know that they know it! So we observe. We watch for what preferences they show spontaneously and regularly. What fruit do they take if there is a fruit bowl on the table? Which DVD gets stopped and rewound over and over again? What do they prefer to drink? What is their favourite activity, even their habitual obsessional behaviour? Often we won’t need to observe specially but will just need to “call to mind” as we will already be aware of all these individual preferences.

Partners in choice

We also watch out for anything that is most definitely not liked as this can form the negative partner in a pair of given choices: the one we know will not be chosen and so contribute to success in our initial teaching.

We also take note of any consistent elements in the daily routine: the order in which items of clothing are put on, which cereal is regularly given for breakfast, what is done immediately after tea. As these are regular and consistent they are likely to be accepted without complaint and so can be used as the positive partner in a pair of given choices.

Tools for “choose”

Laminated symbols or, if the person is a reader, single word cards that just say “choose”: two or three larger (approx. 12cm square) symbols for initial teaching.

Several smaller symbols or words for “choose” for portable use or for inclusion in PECS book.

Cards containing symbol, photo or word (whichever is appropriate for the particular individual) for matching to the items to be chosen. (see “partners” above). At first this may seem strange to be putting a photo, word or symbol of the cereal or trousers beside the real object but it will come clear later when the person moves on to choosing without having sight of the chosen object. We want to make sure that we are all talking about the same thing!

As we will be starting with only two items from which to choose at least one may already have a familiar symbol, photo or word that is already in use either in a PECS book or on a daily programme. I have always used the word “choose” even with non-readers as I made the “oo” in the middle into two eyes so that it was recognisable and so could be used anywhere there was access to a pen and paper. I used the same technique with the word “cool” for a boy whose calm down mantra was “cool it . . . followed by his surname.” “Look” is the third word that lends itself to the eye treatment to emphasise what is being asked.

Introducing “choose” is best done when the person is unaware that anything new or different is happening! When getting dressed you may both know that it is going to be socks after underpants but slip in the large “choose” symbol: “What’s next? You choose. Socks or trousers?” For breakfast every day it’s cereal but have the “choose” card and two boxes out: “Porrridge or cereal? You choose.” Snack time and you are lucky enough to have someone who actually likes to drink water all the time so large “choose” card along with water plus milk: “You choose. Milk or water?” Or perhaps even better “Water or milk” as that avoids the repetition of the last word that is heard.

In the beginning of this learning process it is better not to overdo the choosing. All that is required at this stage is that the person is getting familiar with the word “choose” and that it is a word that has power. It makes something happen and at this point we want to ensure that it’s something good that happens, albeit putting your socks on and getting one step nearer to being fully dressed! So we don’t want to put them off by requiring them to “choose” every single little thing that on the day before just happened without any input from them. The emphasis is different: it’s on the word “choose” and its function of determining “this” rather than “that” from a choice of two.

Once this is established the next stage is to take a small step backwards inasmuch as we ask for the choice to be made without the physical objects being visible. It is only a small step as it takes place just before it’s time for the objects to be produced at their usual time such as the cereal at breakfast, the crisps at snack or the two DVDs at viewing

time. That way we still can’t fail as if there is a sign of uncertainty, panic or frustration we can quickly bring the objects back into sight. And we shall know to practise a bit longer next time before removing them! We need to be sure that the person is definitely able to associate the picture, symbol or word with the actual object and so we need to stick with the familiar until that is certain.

Then we can start getting gradually more adventurous by increasing the frequency of choice-making and its complexity. Here, gradually is the key word and it is well worth going slowly and getting it right. We have to think ahead and ensure that what we offer as a choice is definitely possible. To offer something as a choice and to have it chosen but then have to say it is not available might seem a small thing to us. We are used to choosing something from a restaurant menu and then having the server come back a few minutes later to apologise as it is no longer available. So we choose something else. A minor adjustment to us but it could require a major adjustment and a lot of explanation to someone with autism.

There is a possible domino effect too for some people. If I am a person with whom someone with autism acts confidently because they feel secure in the knowledge that I am not going to let them get to a stage of being out of their own control then I must be trustworthy when

Gail’s Paper & Pens

When it is time for choice to be extended to destinations, activities, restaurant or take away meals we have to “read” our person to see what is an appropriate signifier for them. Then we take the photo, write, draw or checkout the Boardmaker symbol with them to make sure that we will both be talking about the same thing when it comes to choosing.

Finally “choose” comes into its own as an actual period of time similar to “waiting.” It is something positive and “choose time” can even be put on a programme and ticked off when finished and it’s time to move on to something else. When it has reached this stage it is really sophisticated as it doesn’t need any signifiers. This is when there are no demands made and the person is free to have his or her own personal “autistic time” in whatever form it takes: flapping, rocking, twizzling, spinning, colouring in, playing music, computer, repeatedly re-watching the DVD, going under a cover or just simply sitting and doing nothing. At that time it is truly their own choice.

Choosing challenging them to learn a new skill. Therefore it is up to me to think ahead when teaching someone how to choose and check if the choice I am offering is valid. If it is not and there is an ensuing “meltdown” situation, then that is what will be remembered for a while until the trust and confidence is re-established. Meanwhile some valuable learning time is lost and we have to take some steps backward in order to start again.

“But people with autism need everything to be as predictable and consistent as possible. It’s no good springing surprises on them. They need to know ahead of time so that they can process everything. And if something planned and expected has to change ... meltdown alert!” That’s generally what we are advised if we are parents, carers or workers with people with autism.

But normal life isn’t predictable. There are too many variables in it which are often outwith our control. It is terribly hard to achieve consistency once we start adding in more people, different environments, new activities and even the weather. Going on a train trip you can visit the station ahead of time, even get the tickets in advance and go and see the designated platform. So what can go wrong? Well the platform can change for a start. That’s a major one as you don’t find out until you are right in the middle of the station and see it up on the board or, worse still, until you get to the platform you had visited the day before and find out your train is not leaving from there after all.

Swimming: a favourite activity which regularly happens on a Wednesday morning. Except a fault has occurred in the heating system and the pool is too cold for public use. It looks the same as ever. All that water there ready for us to swim in but we are not allowed. There are no people in there. This is not right.

At school the music teacher is off sick today. Will there be a replacement teacher for the eleven o’clock music class or will we have to do something entirely different? The timetable gets done first thing in the morning and so what do we put on it? We don’t know yet. We haven’t been told. We don’t have the information but a blank space could cause a huge amount of anxiety.

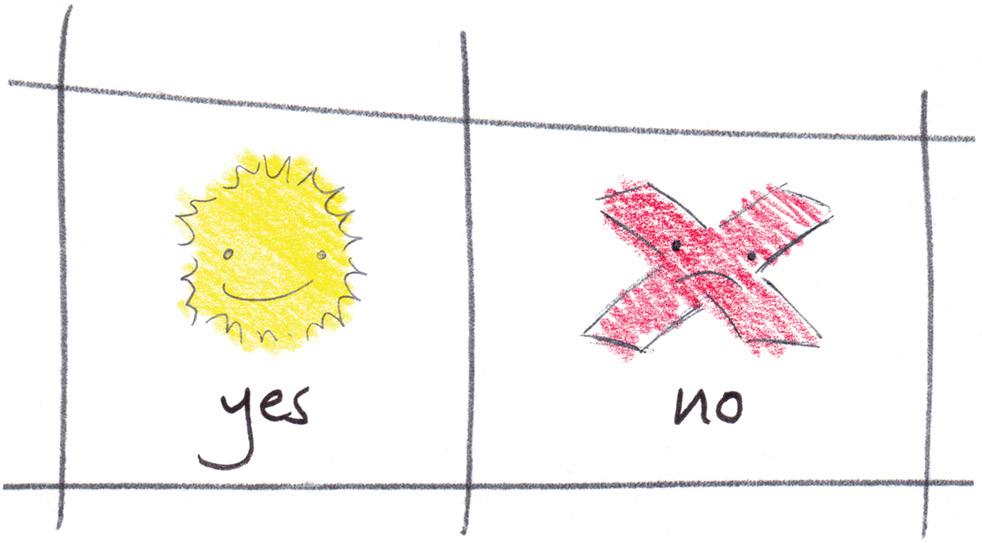

This is when the question mark becomes the most useful symbol of communication. It stands for flexibility which is not usually high in an autistic person’s bank of skills but it can be learned and when it is understood and accepted the world of everyday life becomes a much more positive place.

In my usage of it, “question mark” is synonymous with “I don’t know yet” or preferably “We don’t know yet.” The quotation marks around “question mark” are deliberate as that is how I refer to this sign “?” when using it. It is similar to “waiting” inasmuch as it takes on a role of being an action, an event in its own right. It can be put on a timetable, on an individual schedule or on a pocket symbol for use when away from base. Similar to “waiting” it comes in useful anywhere. So if there is something we are not sure about when doing the morning programme for instance it can take its place in the midst of the known fixtures: e.g. breakfast, bus, swimming, snack, ?, shopping, lunch etc. That is, as long as the programme user knows what it is about. It can buy us time if we are out somewhere and something changes unexpectedly and outwith our control. Having “question mark” and its

Question Mark?

meaning of “We don’t know but we’ll find out” validated as an event, as a period of time in its own right fills the void which can cause anxiety. Better still if it is partnered with “waiting” in communication such as: “We’re waiting to find out.” “We’re waiting to ask the man.” “We’re waiting for the board to change.” “While we are waiting we can just ... ”

The process of understanding “question mark” is similar to that of learning to understand “waiting.” Start with a familiar and well accepted activity that you do know is going to happen but pretend you don’t know. That’s when the symbol “?” gets introduced along with its name “question mark.” It’s sometimes a good idea to laminate a couple of symbols for the introductory time in case they are not immediately well received. Then they will survive for use on another day!

We can also introduce “wondering questions” in lots of other situations, always accompanied by the symbol. In stories: “I wonder what happens next?” In number work: “I wonder what the answer will be?” “How much money is on the table?” And the one that’s sure to elicit a successful response: just before a favourite activity: “I wonder what’s next?”

In the beginning we do not want the uncertainty to last too long and so we can create opportunities to acceptably replace the question mark fairly quickly with “the answer” once we have found out what we don’t

Paper & Pens

know. These opportunities could include going to ask a person who will know the answer to the query, phoning to check arrangements or looking on the internet to find opening or bus times.

If we have already established the understanding of “waiting” we can start to combine the two processes. Maybe we have to “wait” until a certain time for the answer to our “question mark.” If so we might need to mark the time on the clock or write it down or set the timer to indicate an end to this “waiting” and the end, hopefully if we have planned it correctly, will be that we get an answer to the question and can move on.

Maybe we have to wait until a certain person comes to tell us our answer. If so we could have a picture of the person or their name written down so that we can keep reassuringly on track. “We’re waiting for ... ”