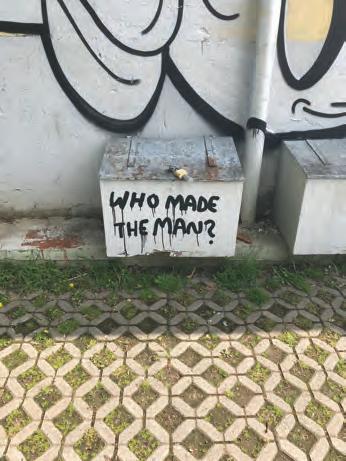

‘There’s no such thing as bad beer,’ proposes Reyner Banham, one of the greatest critics of the last century, in his review of a brewery’s new branding, republished here in a miniretrospective of his writing for this magazine. Which begs the question of whether we might substitute art for beer (imagine that…) and state that, while there are degrees of betterment, any art is always better than no art. ArtReview decided to test the hypothesis by attending the opening of the Venice Biennale. The answer was no, but you’ll want to take a look at the reasoning behind that conclusion by turning to the reviews section.

That ‘no’, ArtReview hastens to add, isn’t to diminish the importance of art but to assert it. It seems obvious to ArtReview that visual culture – and this is perhaps where art more closely resembles beer – influences how you see and act upon the world, whether for better or worse. Misogynistic representations of women in canonical art as much as contemporary advertising, to take just one negative example, continue to have real consequences. The flipside – and here ArtReview’s analogy breaks down disastrously – is that art can also work against those effects: can help you to see more clearly, or at least from different perspectives. It was with this aim that Penny Slinger burst onto London’s art scene during the 1960s with a radically new way of seeing the world that undermined the existing conventions. Yet perhaps art has its limits: just as soon as she was making a name for herself, Slinger disappeared from the artworld, stopped making and pursued her otherworldly interests through the fields of philosophy and tantric sex. It is a depressing irony then that those with the greatest faith in the power of images and artefacts to expand how people think and act are those who would

wish, for that same reason, to destroy them. Michael Rakowitz has given himself the herculean task of remaking – or ‘reimagining’ – the 7,000 objects registered as lost or destroyed during the Iraq wars. He is not doing this for art’s sake, mind you, but because these objects, and culture in general, are the very things that make up our human identity.

If all this sounds a bit abstract (it’s best to leave that sort of pontificating to well after the sun has gone over the yardarm), then the relationship between art and everyday life has preoccupied Stephen Shore ever since his teens, when the aspiring fourteen-year-old photographer showed admirable chutzpah by walking into the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and selling three prints to its director. Shore talks to ArtReview about his early bodies of work that transformed vernacular American objects and scenes into the extraordinary, about his Instagram account and about a new series of photographs that focus on the minutiae of what surrounds him. The British artist Ryan Gander, meanwhile, plays cat-and-mouse with his audience’s presumptions about what art should look like and how it should distinguish itself from its surroundings. By different means, both Shore and Gander invite us to attend more closely to every aspect of the world around us. An invitation ArtReview, inspired by Reyner Banham, is happy to accept, perhaps with a trip to the pub. To inspect the beermats, you understand… ArtReview and after

Sign up to our newsletter at artreview.com/subscribe and be the first to receive details of our upcoming events and the latest art news

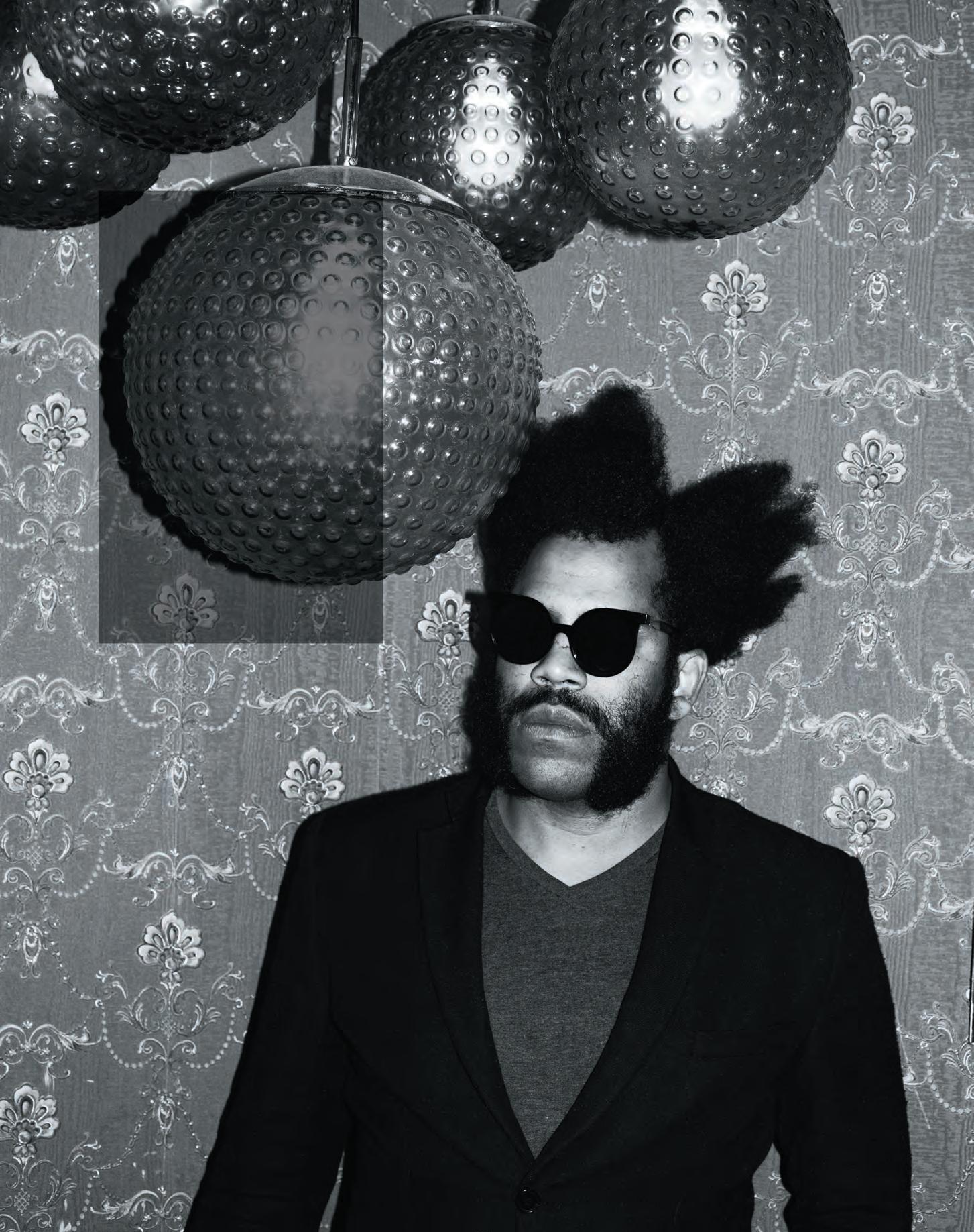

“ The absurdity of minor objects telling a major story is something I seek out”Interview by Oliver Basciano Portrait by Mikael Gregorsky

For almost 3,000 years, the city of Nineveh, near Mosul in modern-day Iraq, was protected by a 30-tonne, 4.5m-high stone lamassu stationed at its gates. The Assyrian deity takes the form of a winged bull (at other times a lion) with a human head. In 2015 members of IS used a pneumatic drill to gouge out its eyes and subsequently destroyed the city’s ancient guardian. Then, in March 2018, the lamassu reappeared. This time beneath Admiral Nelson’s watchful eye in London’s Trafalgar Square. And with reincarnation came reinvention: what once was stone is now constituted of 10,500 cans formerly containing Iraqi date syrup.

This public art commission, located on the square’s Fourth Plinth, is a work by American artist Michael Rakowitz, who has mined the Iraqi heritage of his grandparents, who left the country during the 1940s, in a number of open-ended projects. One of these, The invisible enemy should not exist (2007–; the title translates names of the ancient Babylonian processional way through the Ishtar Gate), involves the mammoth task of reimagining looted or destroyed Iraqi antiquities using food packaging available in Middle Eastern food shops in the West. With over 7,000 artefacts registered as lost, he has a long way to go.

Yet his projects involve much more than the production of objects: in 2010 in Ramallah he restaged The Beatles’ acrimonious last concert as an analogy for the Israel-Palestine conflict; in 2013 he opened an Iraqi-Jewish restaurant in Dubai with menus put together under headings such as ‘Bitter’, ‘Sweet’ and ‘Sour’; during Hungary’s 2006 elections, Rakowitz created a series of architectural collages riffing on ‘utopia’ on the streets of Budapest in collaboration with members of the public. The artist posits that culture, whether presented in museums, or that which is passed on via the kitchen or in music, is what makes us; consequently Rakowitz is vociferous in its defense, protesting against what he sees as its abuse through “artwashing” by corporate powers or governments. Ahead of a return to the UK , for a survey of the artist’s work at Whitechapel Gallery, and having withdrawn from exhibitions at the Whitney Museum and the Jewish

Museum, both in New York, ArtReview met with Rakowitz to discuss cultural heritage, institutional ethics and his take on the history of art.

ARTREVIEW Is there a particular work from your past that drove you towards the approach to art you have today?

MICHAEL RAKOWITZ The work that I’ve returned to every winter since 1998, paraSITE [in which inflatable polyethylene shelters for the homeless are attached to the exterior

capitalism and a government structure. That education came from slowing down: from listening more than speaking. Also finding a way in which I can foreground what I am interested in, as an artist, in terms of making things and still practice social engagement.

AR There’s been a growth in architecture that acts against the homeless: public benches with arms that prevent people from lying down, studs on walls. Was paraSITE a response to this trend, or did it stem from a more instinctive reaction to the problem of homelessness?

heating vents of buildings] continues to teach me a great deal. It’s the work from which so many of my projects have been spun: the engagement with people who are rough sleepers taught me what it means to be a citizen without being accepted and how a work could wield some kind of resistance against

MR Initially it came from going to the Middle East for the first time. I wanted to look at the architecture of Palestinian refugee camps where, in some cases, they were replicating the facades of buildings that the Israelis had bulldozed. I went on an architectural residency to Jordan in the winter of 1997, but the Jordanian government did not want us anywhere near the refugee camps, so I ended up being shepherded into the desert to look at the Bedouin. All this is much romanticised, but one thing the Bedouin did every night was set up their tents in response to the wind patterns. It was a very beautiful detail, but I had no idea what to do with it. When I got back to Boston that winter, I saw a homeless person sleeping underneath the vent of a building, where the warm air was coming from. The HVAC [heating, ventilation and air conditioning] system was keeping this person alive. This was another kind of a wind pattern and another kind of nomadism. I was made aware of the anti-homeless devices you’re talking about by a guy named Keith in Boston, one of the folks I was designing for. He pointed out that the air vents in Harvard Square that they used to sleep on were suddenly given a secondary metal structure that created a tilt so they couldn’t lie down. The shelters enabled them to siphon off the warm air. It is insidious how cities have made it imperative that you be in continual motion, unless you’re somehow ‘legal’, in which case you have to pay for the privilege of rest in rent.

AR Your work might be described as ‘social practice’ but I believe you dislike the term. Most artists don’t like labels, but is there something more to it than that?

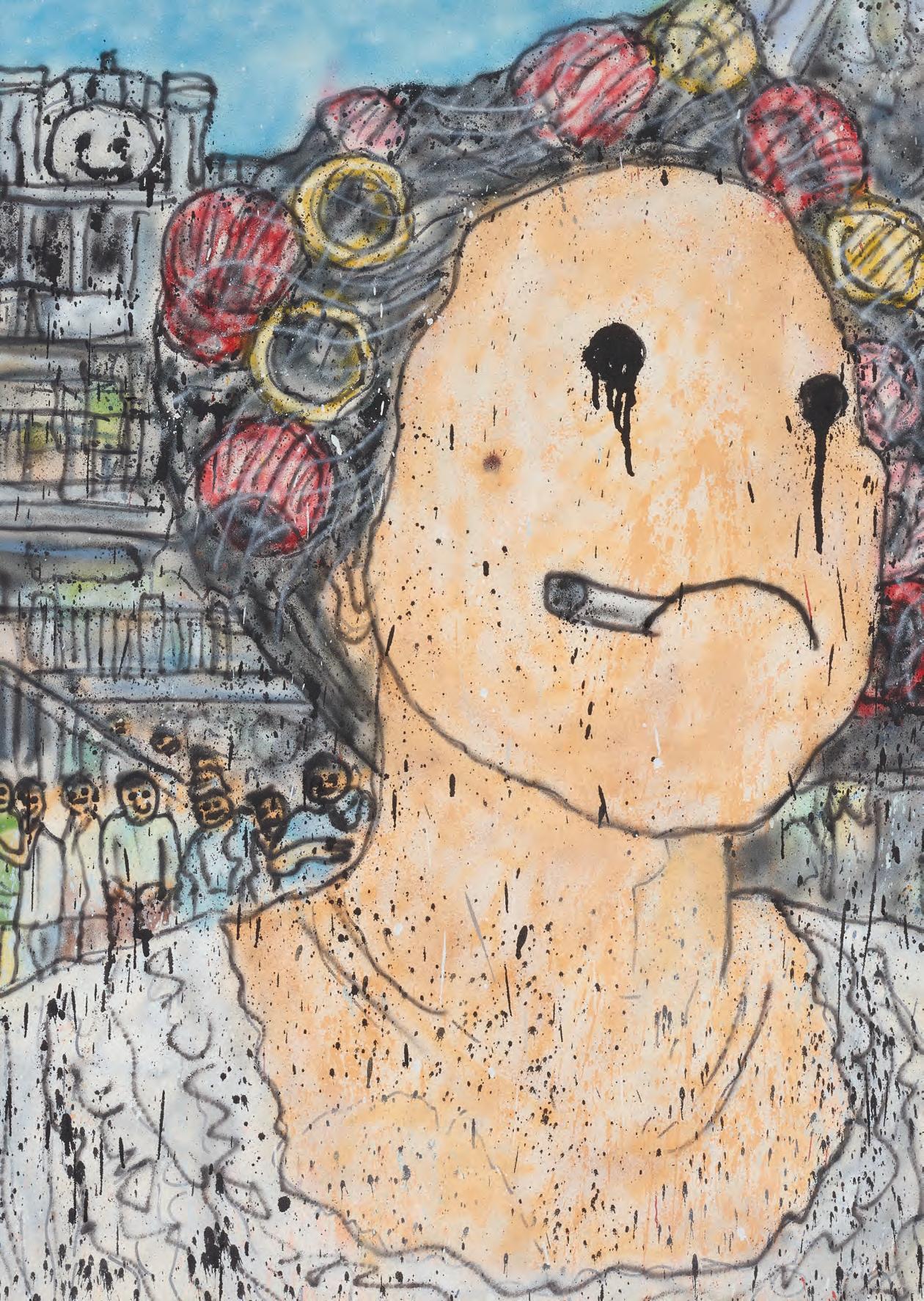

The invite card for Secrets, opening in London on Tuesday, 27 September 1977, reads, ‘This exhibition features the latest work of PENNY SLINGER , including unique doll’s houses, psycho-surrealist body-prints, the original photo-collages of “AN EXORCISM ”… and a new series of collages which explore Tantric erotic themes. This exhibition is the last public showing of her work in this country.’ For the 30 years that followed, the artworld would hear nothing more of Penelope Slinger. Departing first for New York, then the Caribbean in 1979, and moving finally to California during the 90s, Slinger continued to make art, but ceased making it in the artworld.

It’s now a decade since Slinger’s work of the 1970s was brought back from obscurity by curators and artists in the UK , beginning with 2009’s Angels of Anarchy: Women Artists and Surrealism at Manchester Art Gallery. But despite that, and the fact that Slinger is championed by, among others, Punk artist Linder Sterling – who credits seeing Slinger’s photobook 50% The Visible Woman (1971) as a key influence on her own confrontational photomontage – little of her work from the later 70s has been shown in public until now. This July, an exhibition at London’s Richard Saltoun gallery puts the focus on Slinger’s ‘Tantric’ collages and Xerox works from the period, many of which were shown in that exhibition of 1977, before Slinger turned her back on the artworld.

Throughout the early 70s – from leaving Chelsea college in 1969, just as ‘Swinging London’ was burning itself out – Slinger created books, photocollages, sculptures, objects and films that articulated a visceral, often traumatic vision of female experience, and the bodily and psychological violence experienced by women in a maledominated world. Drawing on the visual strategies of Surrealism, whose first (male-dominated) generation was by then dying away (André Breton died in 1966, Slinger met an elderly Max Ernst in 1969), Slinger seized Surrealism’s fascination with the subconscious and sexuality, while inverting the Surrealists’ often misogynistic and objectifying celebration of the passive female ‘muse’. Claiming

herself as both subject and object, Slinger declared, ‘I wanted to be my own muse’. In the space of a few years, Slinger created images and objects that, retrospectively, seem to have anticipated later feminist theories about the gendered self’s relationship to language, childbirth and abjection.

If Slinger’s early work confronted misogyny, it did so by a militant celebration of female sexuality. These were the years following the showing, in 1970, of Allen Jones’s grotesque bondage-culture sculptures of women – the notorious Chair, Hatstand and Table (1969) – which had provoked outrage. ‘From the rippling courtesans of Titian… to the fetishised club girls of Allen Jones’, Arts Review’s Peter Fuller observed in 1971, ‘women have always been painted by men, from the man’s point of view, and new theoretical developments, actively being put into practice by women, have shown that that point of view has been humiliating and oppressive’.

Fuller was right to note the ‘theoretical developments’ shaping early feminism. By 1973, Laura Mulvey, in her second article for the recently launched magazine Spare Rib (the first a takedown of Jones’s work), would bring her own strongly psychoanalytical take to Slinger’s work. Writing about Opening, Slinger’s second solo show at Angela Flowers Gallery – objects and photocollages in which Slinger played imagery of food, mouths and vaginas against an iconography of bridal virginity and passivity – Mulvey argued that ‘Until women can confront their own unconscious phantasies, as long as they continue to be captivated by those of men, they will be out of touch with the content of their own minds and victims of the repression which allots them their place in society even to their own satisfaction’.Mulvey’s Freud-heavy take on Slinger found rich pickings in the iconography of Slinger’s work, but when discussing the concluding page of 50% The Visible Woman, Mulvey was uncertain: ‘The last image is of a woman-man, a hermaphrodite. Called a “compromise to form a solution”, it tries to resolve the dilemmas of the birth trauma, the relationship with the mother, the Oedipus complex and the vicissitudes

Editorial

Editor-in-Chief

Mark Rappolt

Editor

David Terrien

Editor (International)

Oliver Basciano

Senior Editor

J.J. Charlesworth

Associate Editors

Ben Eastham

Martin Herbert

Sam Korman

Jonathan T.D. Neil

Assistant Editor

Louise Darblay

Editorial Assistant Fi Churchman

Contributing Editors

Tyler Coburn

Brian Dillon

Chris Fite-Wassilak

Maria Lind

Joshua Mack

Laura McLean-Ferris

Chris Sharp

Design

Art Direction

John Morgan studio

Designers

Isabel Duarte

Pedro Cid Proença office@artreview.com

Publishing

Associate Publisher Moky May mokymay@artreview.com

Finance

Finance Director Lynn Woodward lynnwoodward@artreview.com

Financial Controller

Errol Kennedy-Smith errolkennedysmith@artreview.com

ArtReview is printed by Micropress Printers Ltd. Reprographics by PHMEDIA Copyright of all editorial content in the UK and abroad is held by the publishers, ArtReview Ltd. Reproduction in whole or part is forbidden save with the written permission of the publishers. ArtReview cannot be held responsible for any loss or damage to unsolicited material. ArtReview, ISSN No: 1745-9303, (U S P S No: 21034) is published monthly except in the months of February, July and August by ArtReview Ltd, 1 Honduras Street, London EC1Y o TH , England, United Kingdom. The US annual subscription price is $50. Airfreight and mailing in the USA by WN Shipping USA , 156–15, 146th Avenue, 2nd Floor, Jamaica, NY 11434, USA . Periodicals postage paid at Jamaica NY 11431. US Po STMASTE r : Send address changes to ArtReview, WN Shipping USA , 156–15, 146th Avenue, 2nd Floor, Jamaica, NY 11434, US A

Advertising

UK, Ireland and Australasia

Jenny Rushton jennyrushton@artreview.com

Mainland Europe and Latin America Moky May mokymay@artreview.com

North America and Africa

Debbie Hotz debbiehotz@artreview.com

Asia

Fan Ni fanni@artreview.com

Fashion and Luxury

Charlotte Regan charlotte@cultureshockmedia.co.uk

Production & Circulation

Associate Publisher Allen Fisher allenfisher@artreview.com

Production Manager

Alex Wheelhouse

production@artreview.com

Distribution Consultant Adam Long adam.ican@btinternet.com

Subscriptions

To subscribe online, visit artreview.com/subscribe

ArtReview Subscriptions

Warners Group Publications The Maltings, West Street Bourne, Lincolnshire PE 10 9PH T 44 (0)1778 392038 E art.review@warnersgroup.co.uk

ArtReview Ltd

ArtReview is published by ArtReview Ltd

1 Honduras Street London EC1Y oTH T 44 (0)20 7490 8138

Chairman Dennis Hotz

Managing Director Debbie Hotz

Art and photo credits on the cover

Penny Slinger, Penny as Shakti, 1976. Photo: Nik Douglas. © the artist. Courtesy Richard Saltoun, London on pages 42, 109 and 112 photography by Mikael Gregorsky

Text credits

Words on the spine and on pages 27, 41, 73 and 85 are from Tales from Sri Lanka (2010), by Manel Ratnatunga