architecture arts +

Ricker Notes was originally a periodical for the School of Architecture, edited and published by Architecture students including feature articles, news, poetry, drawings, book reviews and beneficial quotes. The title “Ricker”, refers to Nathan Clifford Ricker, the first graduate of an architecture program in the United States in March of 1873.

This academic year, the School of Architecture is bringing back Ricker Notes in the form of a monthly magazine called Ricker Report. Moving forward, the magazine aims to create a unifying platform to present students with information about the school, upcoming events, architectural clubs and organizations, and articles on different studios, professors, and professionals.

Ricker Report Team

Matt Ehlers | Creator + Editor-In-Chief

Hannah Galkin | Editor

Karolina Chojnowska | Editor + Graphic Design

Nico Hsu | Editor + Graphic Design

Joshua Downes | Editor + Writer

Diego Huacuja | Editor + Marketing

Jessica Stark | Editor + Marketing

Peter Schumacher | Photographer

Bhavi Dalal | Editor

TJ Bayowa | Editor

05 06 10 34 46 56 62 70 84 90

RICKER REPORT MAY 2019 VOL. 01 | ISSUE 05

2

Letter From the Editor

This Month in Architecture

Life - Work Balance

Featuring Tom Loew Society, Economy, & Environment

Featuring Christina Bollo

Family, Fabrication, & Fellowship

Featuring Lowell Miller

Women’s Reunion & Symposium

September 26 - 28, 2019

Inside ARCH 232 Barcelona Program Graduate Review Gallery

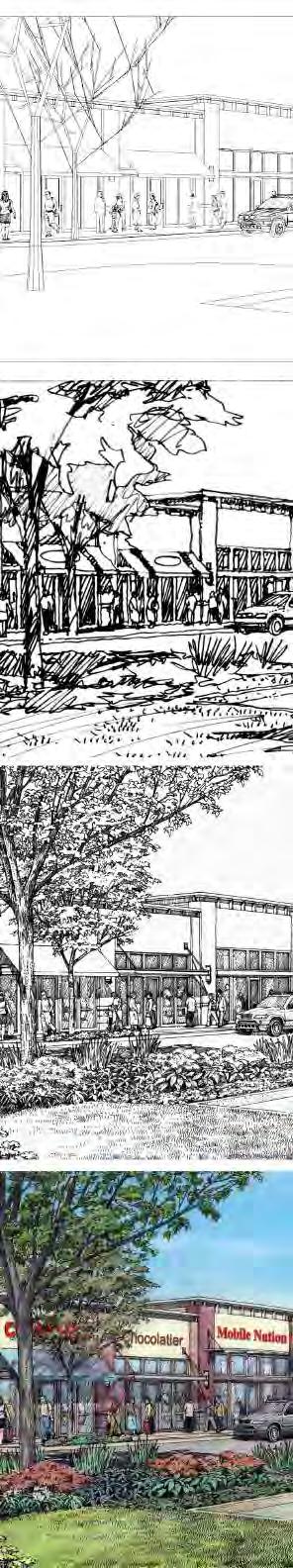

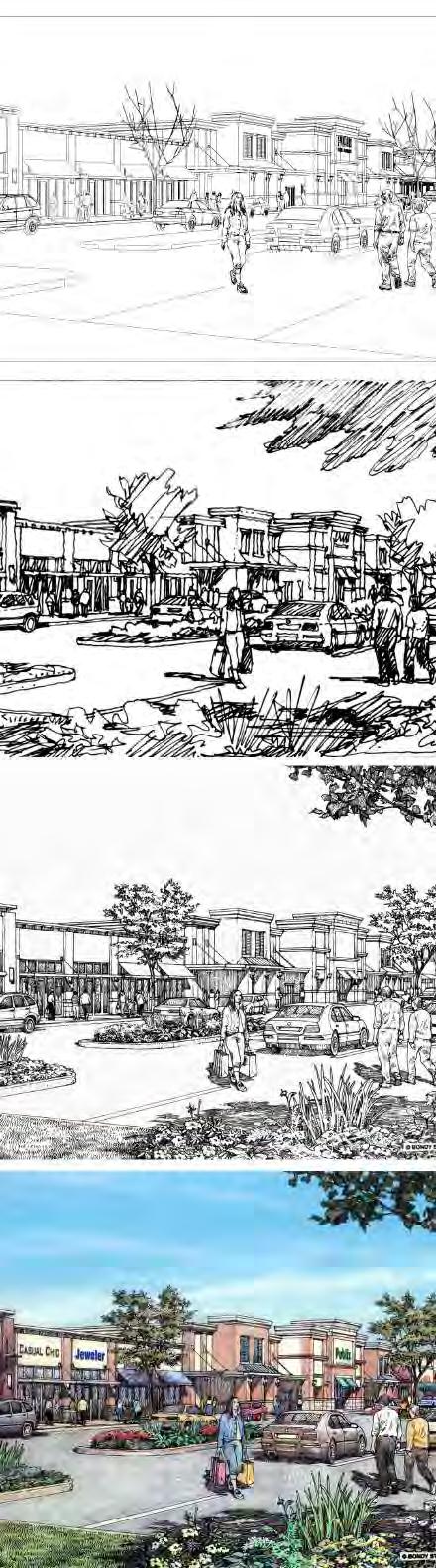

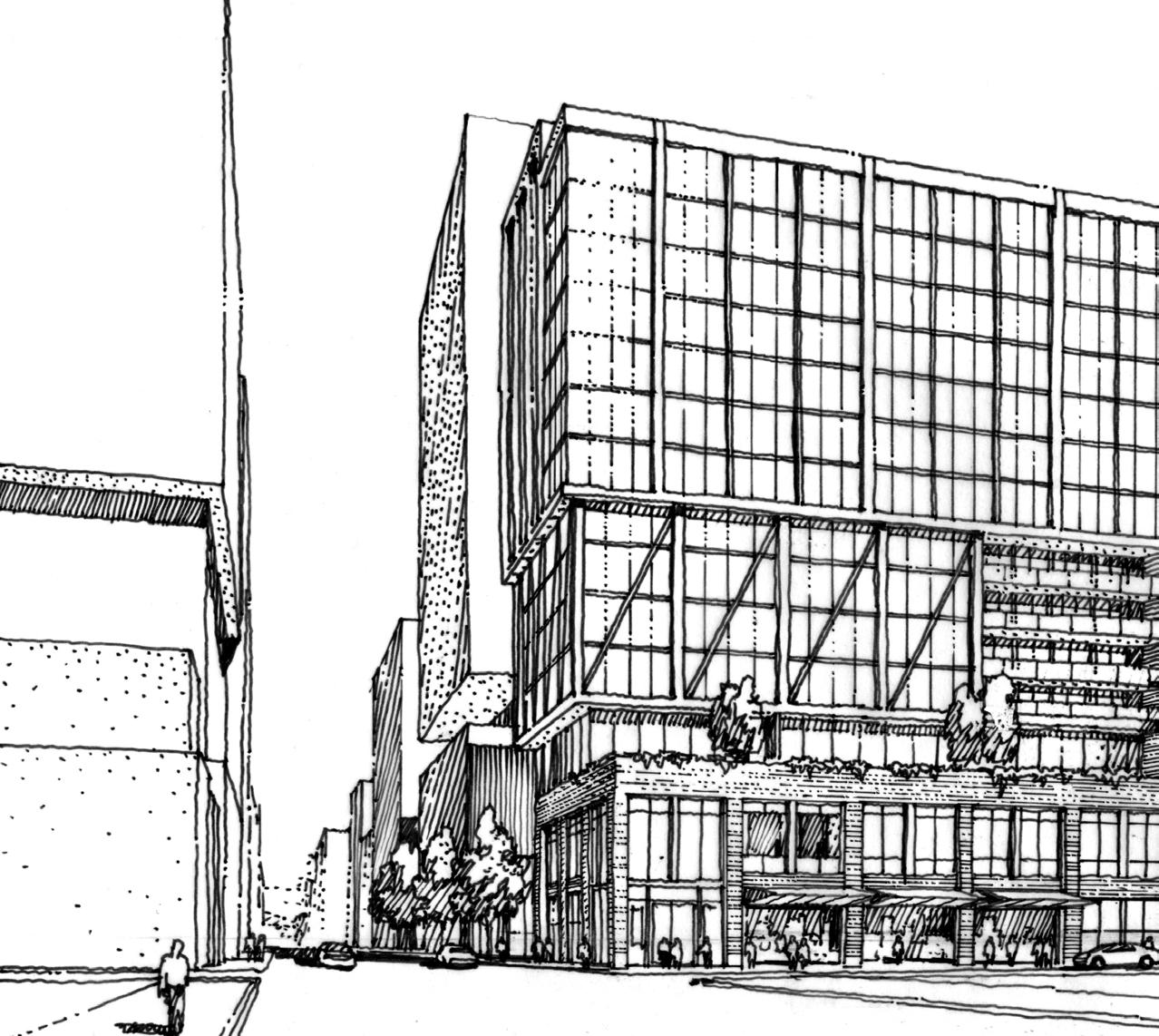

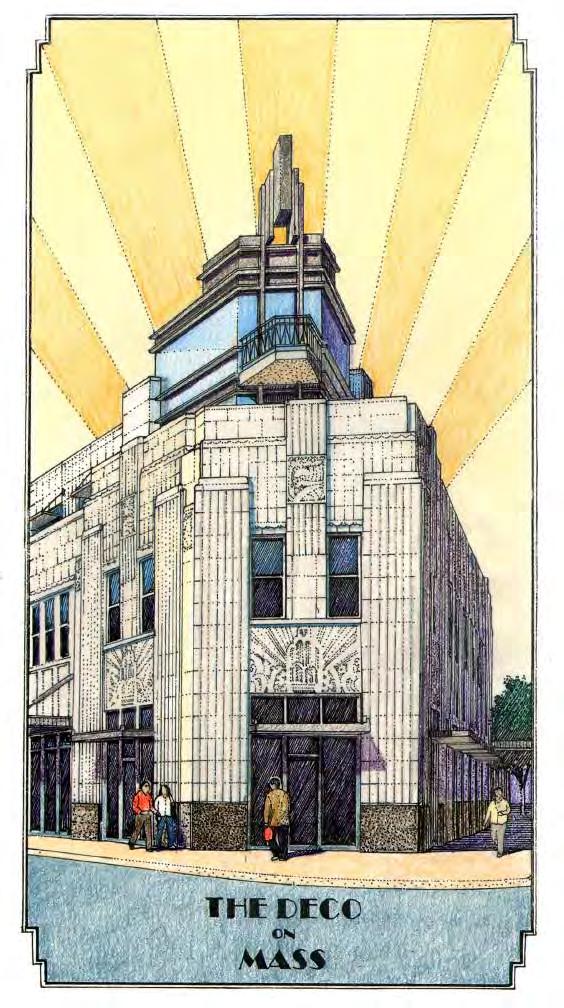

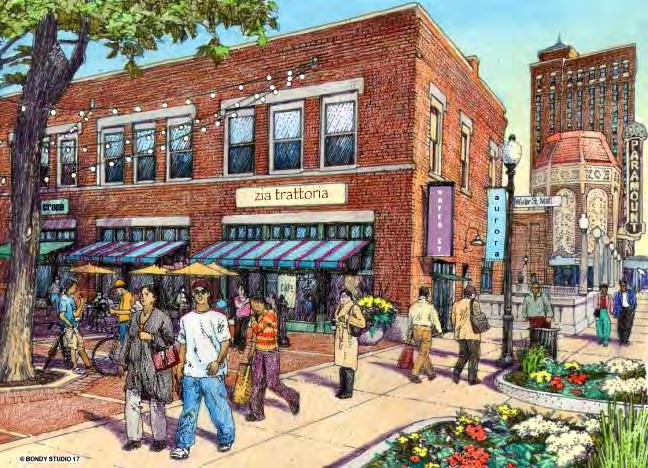

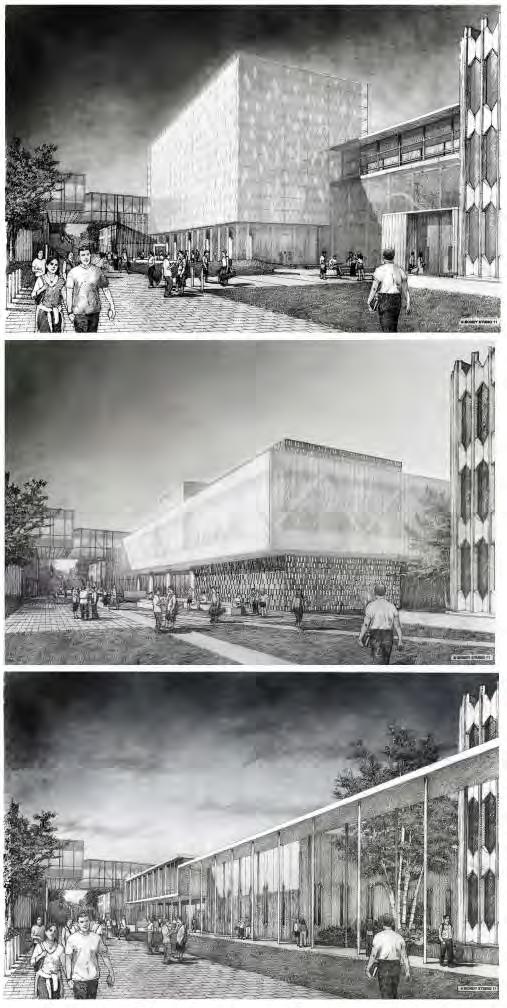

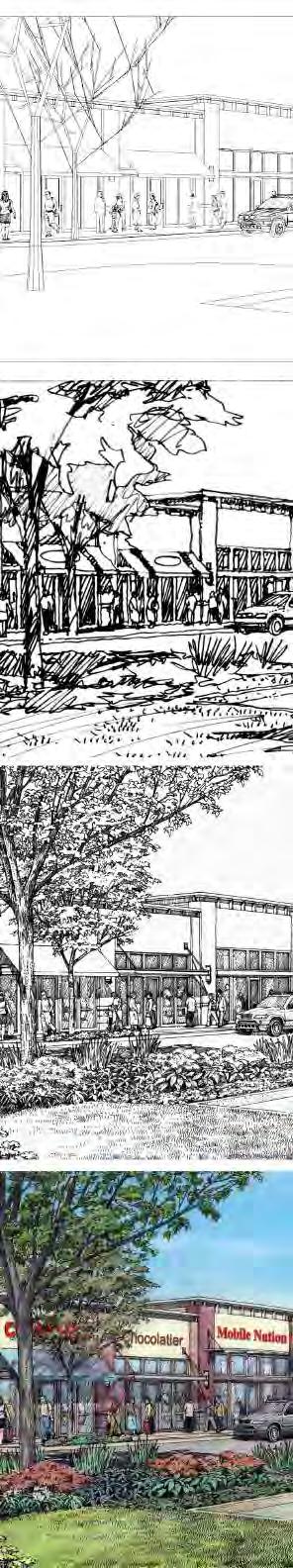

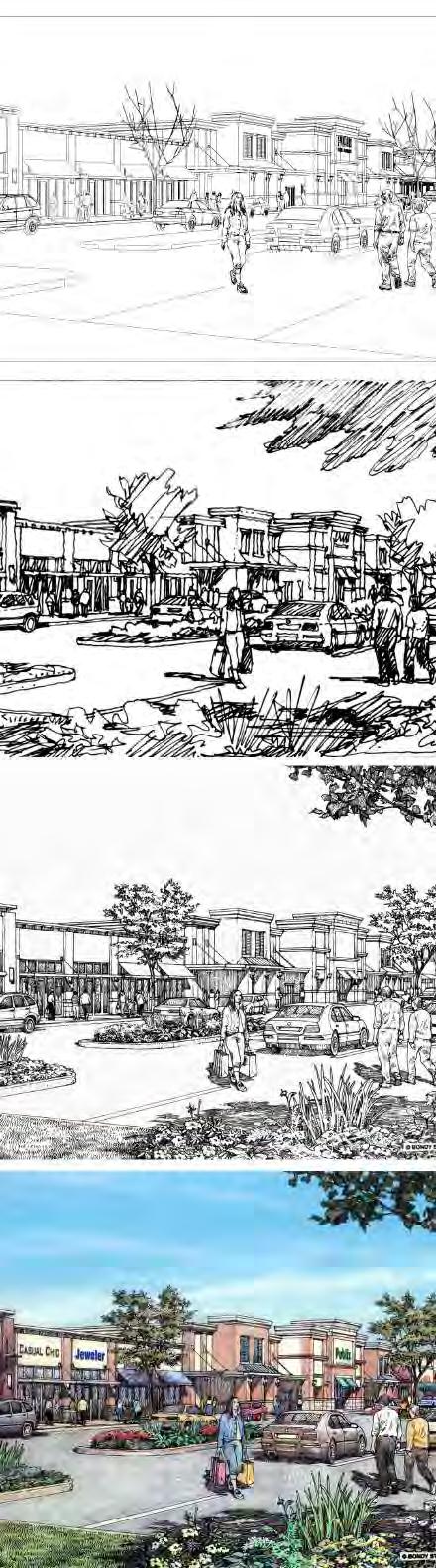

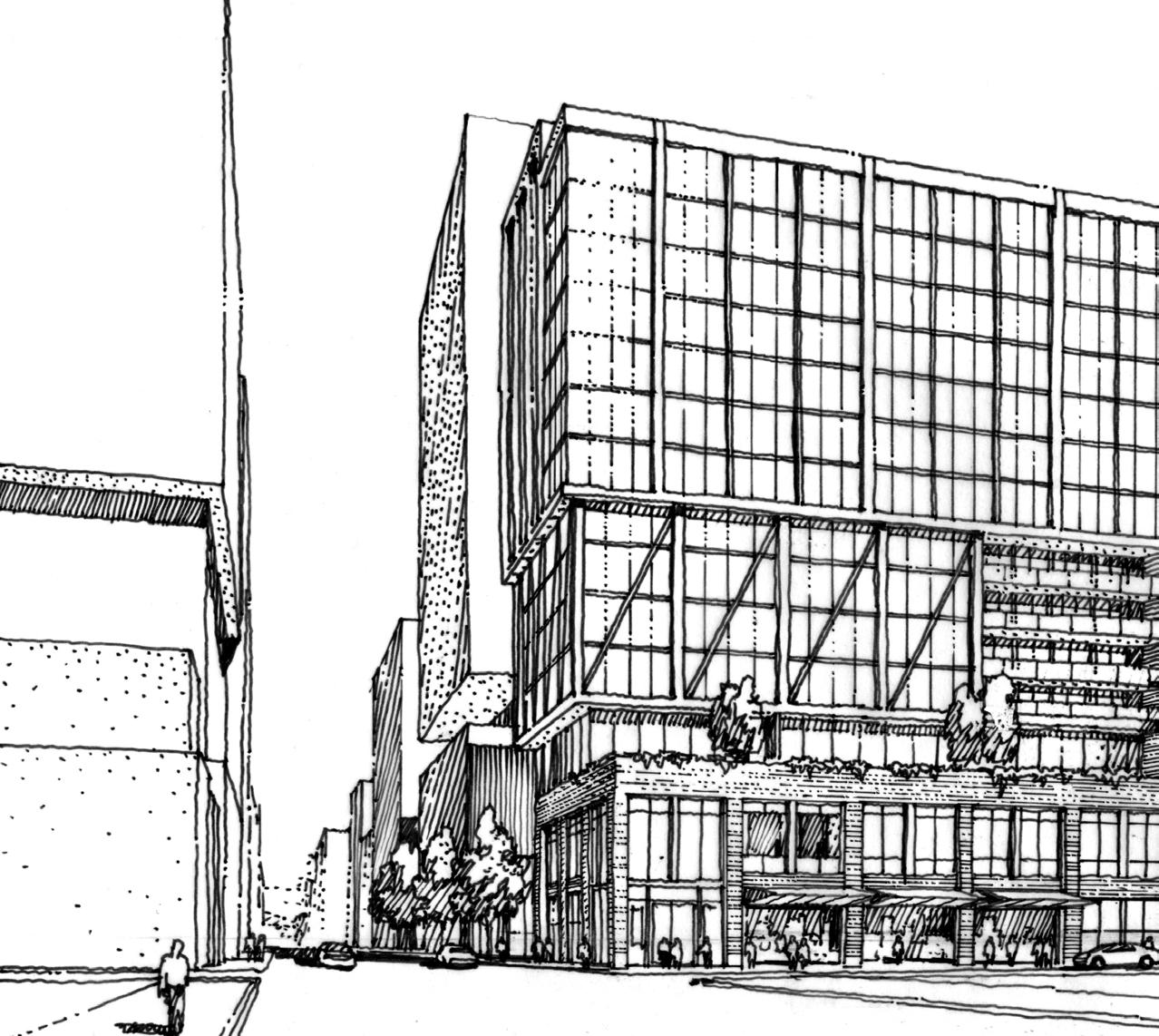

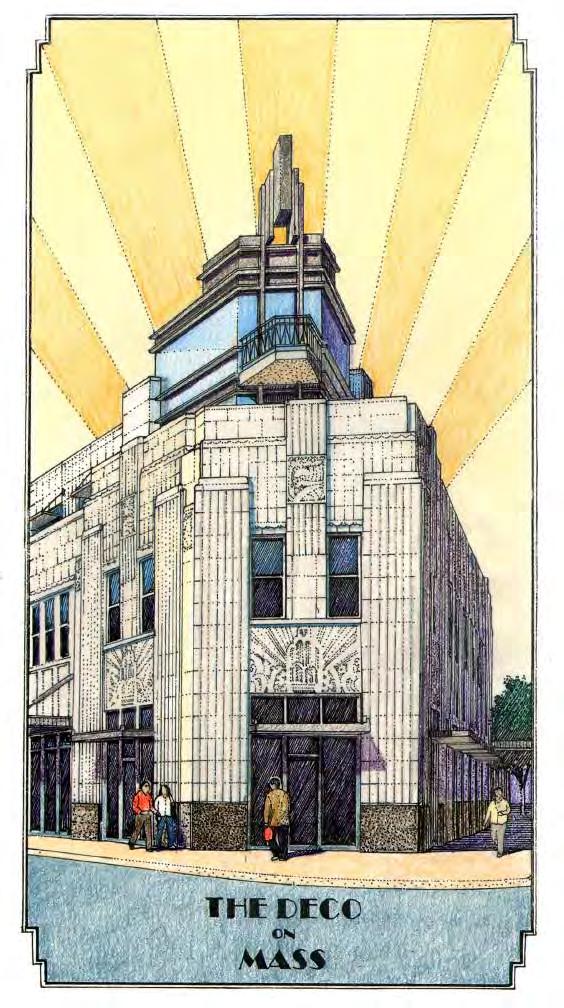

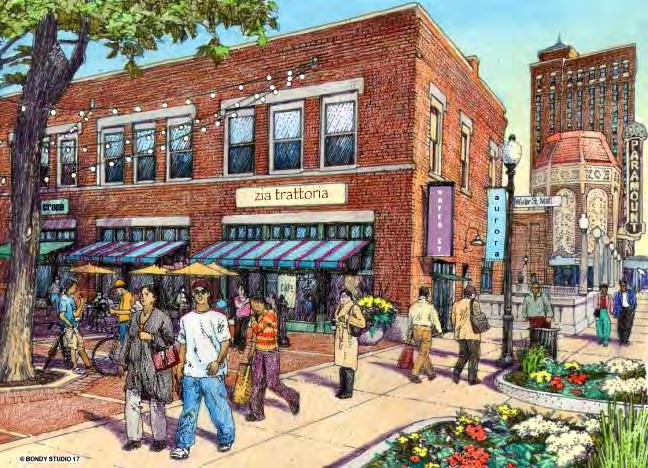

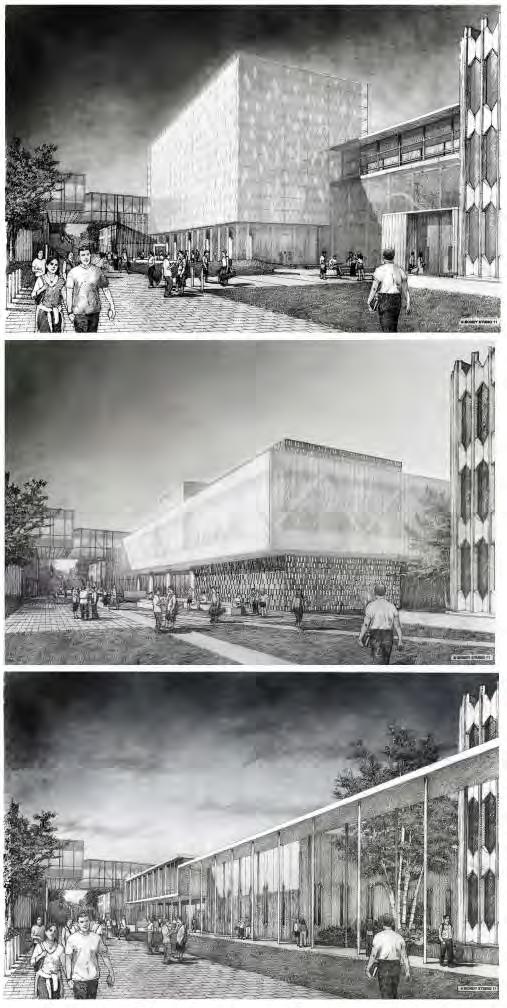

Architectural Illustration

Featuring Bruce Bondy

3

CONTRIBUTORS

RICKER REPORT TEAM

Matt Ehlers

Hannah Galkin

Karolina Chojnowska

Nico Hsu

Joshua Downes

Diego Huacuja

Jessica Stark

Peter Schumacher

Bhavi Dalal

TJ Bayowa

FEATURED

Tom Loew

Christina Bollo

Lowell Miller

Marci Uihlein

Sara Bartumeus

Bruce Bondy

PRINTING + SERVICES

Bruce Colravy

Dixon Printing

105 W John St. Champaign, IL 61820

4

With the upcoming month of May, we enter Mental Health Awareness Month. In the world of architectural educationespecially studio – education entails long work weeks, immense amounts of stress, and potential health issues from lack of sleep and anxiety.

Taking this into consideration, the Ricker Report Team sought out faculty members and professionals that illustrate an admirable live-work balance. These individuals excel not only at the educational/teaching platform, but in professional practice, society, research, and their own personal and family lives. These individuals are mentors to students and aspiring professionals alike. They

EDITOR’S NOTE

convey their passions and professional interests via charisma and encouragement in their educator and professional practice roles. I firmly believe, we as students, have so much to learn from our staff, colleagues, and coworkers we share our days with.

That being said, I feel it necessary to say this selection of faculty and professionals is only a partial depiction of the entire faculty. The entire faculty balances so many incredible feats at the University of Illinois. From research on sustainable materials to deployable structures and housing, our students, faculty, and alumni excel in many fashions.

However, at the end of the day, our health and lifestyle are effected by how we conduct our work weeks and lifestyle. As I continue to learn these principles myself, I stress each and every one of you reading to listen to what these professionals have to offer, and to put mental health, physical health, and sleep first as you approach school and professional practice.

Editor in Chief | M.Arch + M.S.C.E.E. Candidate 2021

5

“Well, my philosophy is that worrying means you suffer twice”

-JK Rowling

This Month in Arch April 2019 & May 2019

Mexico-based architect Rozana Montiel has won the Global Award for Sustainable Architecture for the year 2019. She has won alongside Werner Sobek, Ersen Gursel, Ammar Khammash, and Jorge Lobos. The award was created in 2006 by architect and academic Jana Revedin, awarding five architects each year that “contribute to a more equitable and sustainable development and create an innovative and participatory approach to meet the needs of societies, whether experts in economics, construction or self-development actors for whom sustainability is synonymous with social and urban equity.” The prize has been seen as a contemporary discoverer of cutting edge talent such as Wang Shu and Carin Smuts. Rozana Montiel, whose projects focus on social participation in her projects, has previously won the MCHAP prize in 2018 and the Architecture Review’s Women in Architecture prize in 2017. The award ceremony will take place in Paris on May 13th.

6

Rozana Montiel Wins the Global Award for Sustainable Architecture 2019

Rozana Montiel Wins the Global Award for Sustainable Architecture 2019.” ArchDaily, 5 Apr. 2019, www.archdaily.com/914532/rozana-montiel-wins-the-global-award-for-sustainable-architecture-2019.

Baldwin, Eric. “RIBA Launches Gender Pay Guidance for Firms.” ArchDaily, ArchDaily, 5 Apr. 2019, www.archdaily.com/9 l 45 l l/riba-launches-gender-pay-guidance-for-firms.

RIBA Launches Gender Pay Guidance for Firms

A new directive has been issued by the Royal Institute of British Architects to close the gender pay gap between men and women architects as a means to create a more inclusive environment. The guidance, named “Close the Gap - Improving Gender Equality in Practice”, outlines the best measures and initiatives an architectural manager can use to separate an individual’s career from one’s gender identity. The news follows RIBA’s own 2018 study on the pay gap that came out earlier this month. RIBA President, Ben Derbyshire, said: “There is no place for discrimination in our profession. Yet, almost 50 years after equal pay legislation came into force in the UK, significant instances of inequality remain. Change is long overdue and all of us - employers, employees and the RIBA - have a vital role to play.” A core group of RIBA supporting practices have already signed the pledge, which encourages unbiased recruitment and promotion, flexible working patterns, and techniques to operate a practice fairly. The guidance is accompanied by a tweetable hashtag to show one is taking the pledge: #CloseTheGap.

Serpentine Bans Use of Unpaid Interns for 2019 Pavilion Design Team

Following controversy surrounding the use of unpaid interns, Junya lshigami + Associates, designers of the Serpentine Pavilion in London, have been ordered by Serpentine to pay all their staff. This comes after an email that was reportedly seen by The Architect’s Journal that detailed how one particular intern at the company had a lack of pay, six-day work weeks, and extended hours. Allegedly Serpentine was unaware of the intern and the conditions, and after a discussion with Junya lshigami + Associates released a statement on March 27th that any unpaid internship would not be allowed on the 2019 design team, or in the future for that matter. Although unpaid internships are more common in Junya lshigami + Associates’ home country of Japan, in Europe a six-day week consisting of extended hours with below minimum wage pay would be illegal under the EU, and has been banned by the Royal Institute of British Architects since 2011.

7

Walsh, Niall Patrick. “Serpentine Bans Use of Unpaid Interns for 2019 Pavilion Design Team.” ArchDaily, ArchDaily, 28 Mar. 2019, www.archdaily.com/913982/serpentine-bans-use-of-unpaidintems-for-2019-pavi lion-design-team.

The Shed Opens in New York’s Hudson Yards

After more than a decade of work Diller Scofidio + Renfro and Rockwell Group’s Shed has opened in New York’s Hudson Yards, connected to the Highline at 30th Street. The 17,000 foot multi-purpose building contains multiple galleries, the 500 seat Griffin Theater, and the Mccourt, itself a multi-use space for large installations and social performances. On the top floor are the Tisch Skylights, which holds a lab for local artists and both rehearsal and event spaces. The most spectacular element of the building however is the 120 foot telescoping shell that covers the building, made of ethylene tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE), which can be extended out for larger performances. Liz Diller of DS+R defines the Shed as “Eleven years in the making ... opening its doors to the public as a perpetual workin-progress. I see the building as an ‘architecture of infrastructure,’ all muscle, no fat, and responsive to the ever-changing needs of artists into a future we cannot predict. Success for me would mean that the building would stand up to challenges presented by artists, while challenging them back in a fruitful dialogue.”’ The opening was accompanied by a five night concert series directed by Steve McQueen with Quincy Jones and Maureen Mahon, which celebrates the global influence of African American music.

Studio Gang to Lead Winning Chicago O’Hare Airport Expansion

Studio Gang, headed by the University of Illinois’ own Jeanne Gang, has won the competition to lead the O’Hare 21 International Terminal extension. Their bid was successful due to their intent of celebrating Chicago’s history itself. The winning submission consists of three major volumes that converge around a main hub, merging the terminal and concourse into one large building. The overall profile therefore looks similar to a Y, which invokes the branching of the Chicago River. At the point where these volumes meet is a six-pointed glass skylight, reminiscent of the type of star used on the Chicago flag. Studio Gang beat out other leading firms including SOM, Bjarke Ingels Group, and Calatrava. Do not fret for the runners up though: the remaining firms will have a chance to design two smaller satellite concourses to be built west of Terminal 1. This will be the first expansion of O’Hare in 25 years, and will hopefully be completed by 2023.

Baldwin, Eric. “Noor Completes Reconstruction of the Mirror Palace in Iran.” ArchDaily, ArchDaily, 27 Mar. 2019, www.archdaily.com/913 961 /noor-completesreconstruction-of-the-mirror-palacein-iran.

Baldwin, Eric. “The Shed Opens in New York’s Hudson Yards.” ArchDaily, ArchDai ly, 5 Apr. 2019, www.archdaily.com/914450/the-shed-opens-in-new-yorks-hudson-yards.

8

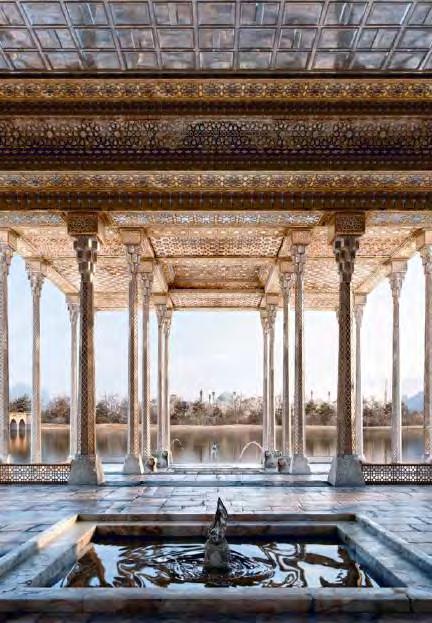

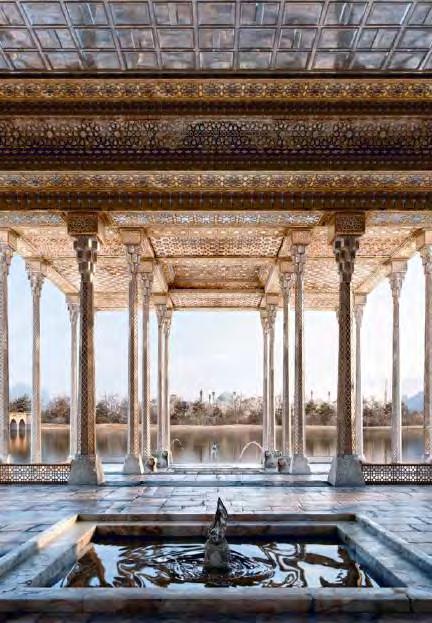

Noor Completes Reconstruction of the Mirror Palace in Iran

The Ayine Khaneh Palace, also known as the Mirror Palace, has been digitally reconstructed by Noor Art & Architecture Studio. Led by head architect Mohammad Yazi Rad, the digital reconstruction stems from historic plans and written documents, and is meant to create a cultural structure that would bring attention to both the Safavid era and Persian architecture. As the capital of the Safavid Dynasty, Isfahan became inundated with great building projects, the Ayine Khaneh Palace being the jewel amongst them. During the period of its’ physical existence it was located on the southern bank of the Zayandehrood river in a garden called Saa’dat Abad, which was built in the Shah Sao and Shah Abbas II era, in the 16th century. The walls were decorated with mirrors and paintings, and the project featured the use of marble. In the central part of the porch, there was a marble pool with fountains spouting from the mouths of four stone lions. These descriptions drew similarities amongst historians to the Chehel Sotoun Palace. The Palace had been destroyed in 1891 by the then governor of Isfahan Zella Soltan. However, though the use of technology, budding architects and historians can access this beautiful piece of culture once again.

9

Baldwin, Eric. “Studio Gang to Lead Winning Chicago O’Hare Airport Expansion.” ArchDaily, ArchDaily, 28 Mar. 2019, www.archdaily.com/913 991 / studio-ord-wins-chicago-ohare-airport-expansion.

LIFE - WORK BALANCE

BALANCE

JOURNEY

TRANSFERABLE SKILLS

THOROUGHNESS PROCESS

DISTILLATIONS

“Process, in traveling, to me. You appreciate more. Understanding you are at in a journey important as the

Master of Architecture, University of Illinois (1991)

Bachelor of Science in Architectural Studies (1985)

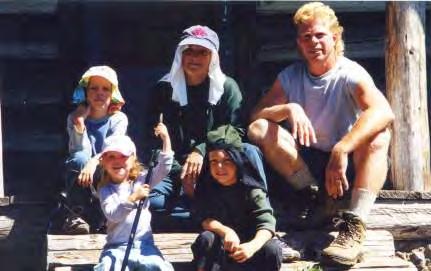

Since 1988, Tom has owned and developed a Design/Build firm in Champaign, Illinois specializing in custom designed homes and remodels. He also actively balances the complexities of live-work balance. His life is interwoven with the rhythms of life through family, professional work, educating, and travel. Tom’s ability to guide and instruct others though the process of home design and construction is a trademark of his professional practice. This endeavor has proven to be a fulfilling life’s work, which draws from a rich architectural education from the University of Illinois. Over the course of 30 plus years, Tom has demonstrated an unmistakable ability to synthesize concepts and programming requirements and to translate these objectives into built works. With well over 100 built projects, Tom’s work embodies both an aptitude for the process of home design as well as a refined skill of hands-on craftsmanship with respect to numerous building trades. While Tom’s passion comes from a desire to see the creation of meaningful architectural form and space, his deep care for his clients and professionalism have produced longstanding relationships in addition to a long list of rewarding projects.

13

Tom Loew

Adjunct Professor | Builder | Designer | Father

is important appreciate process Understanding where journey is just as destination.”

The Journey

Ricker Report Team: Balancing multiple worlds, a professional practice, teaching, advising young architects, a family, and an active lifestyle of traveling, I was curious where your interests began with architecture and design?

Tom Loew: It’s hard to identify one specific moment that was a decision point for my career path. I believe that I was influenced by many factors alone my journey. From my earliest memories regarding the world of architecture, I didn’t really seem to be motivated upon the idea of architecture as a professional objective as much as it was about a love for creating space and the experience of engaging with it. I probably built my first real structure when I was 10 or 11. We had a neighborhood trilevel fort which stood about 16 ft tall and housed an underground room where everyone in the neighborhood came to play. I first learned to draw precise drafting details in Junior high school and then again in high school architectural classes. I can still remember how this experience transformed my understanding of measurements and mathematics into a three-dimensional world of rhythms and spatial relationships.

From my vantage point today, I look back with a lot of admiration for the things I learned in my time at the University of Illinois. This place was formative, in the way that I think about life, and the way that I conduct practice. As an 18/19 year old, you don’t truly understand while going through school that you are being trained for much more than just the profession of architecture.

It is necessary to say it was a series of things that gave me the opportunities that I have followed in

14

my life to become an architect. That idea is something that is not at the forefront of your mind when becoming an architect. But it is the playful sides of life and the interactions with moveable objects and the built environment that allowed me to immerse myself in architecture as a profession. We played life in the environments that we made. Whether that be jumping on a train and running around or exploring the depths of nature in forests.

than necessarily exactly what I learned. You know, it was the Jim Warfield’s, the Art Kaha’s, Claude Winkelhake, Jack Baker, Dave Chasco, Botand Bognar, and a whole list more of people who were influential in helping me navigate along my journey. This idea of mentorship is something I hold close as a guiding principle. Each of these people challenged my way of thinking; they provided an invaluable perspective of life.

While I was a junior in our School of Architecture I began to write the outline for my graduate Thesis.

RR: Are there specific skill sets which the academic experience trained or prepared you for?

TL: We have always had a wealth of diverse knowledge on the UIUC campus.

When you ask me about the things I learned, I know that the academics and excellence of the teaching have grounded so much of what I do today; yet, I could tell you about the people I learned from more

What started as concern over the housing problems in the large urban areas of Mexico led to an intimate study of the indigenous architectures of the country. I still remember the guidance of both Claude Winkelhake and Jim Warfield. Warfield encouraged me to travel to Mexico to work on my thesis. He asked, “how do you understand what a legitimate design proposition is without knowing the people you are designing for?”

16 “

the moments we invite in our present, may ultimately serve as the mechanism which sets our trajectory and velocity.”

18

19

“

...we think that tomorrow is simply another day, Yet we know so little about time. We measure and measure... perhaps with only a handful of tools...”

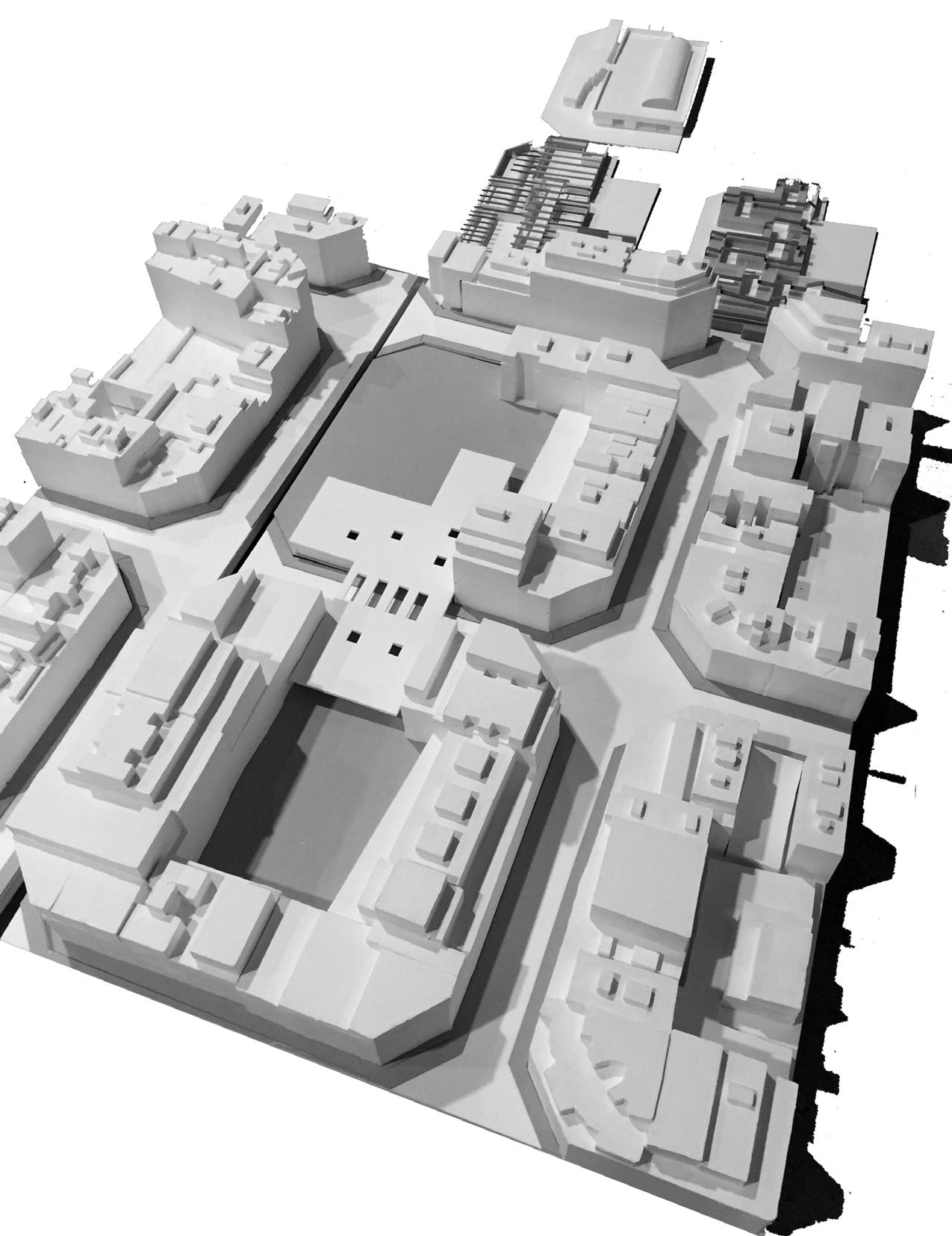

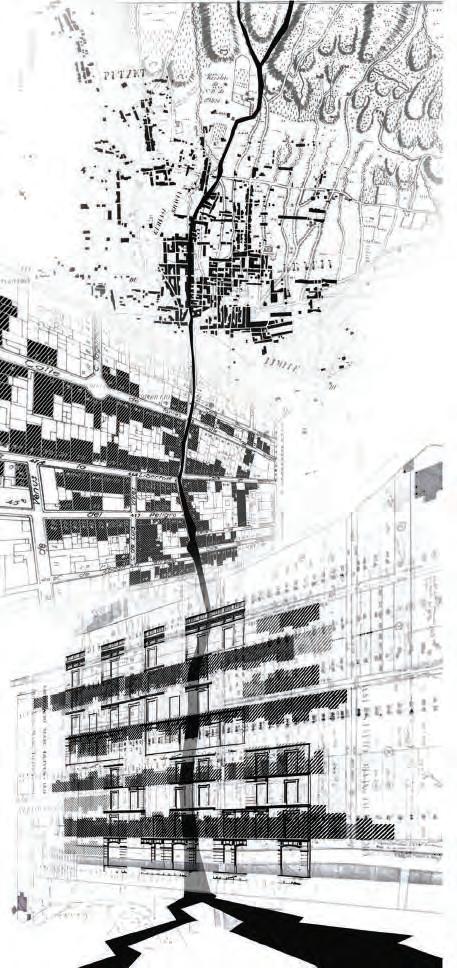

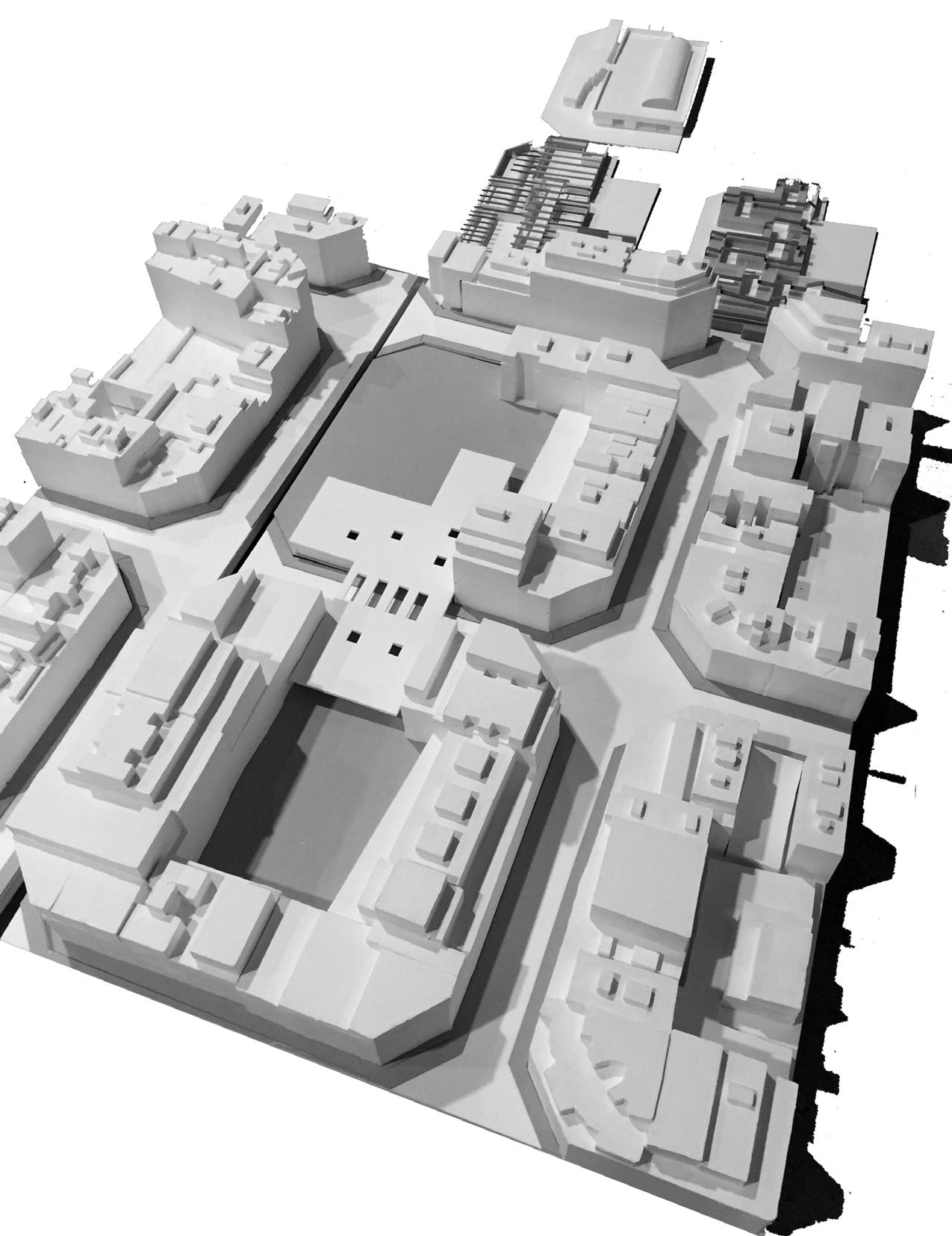

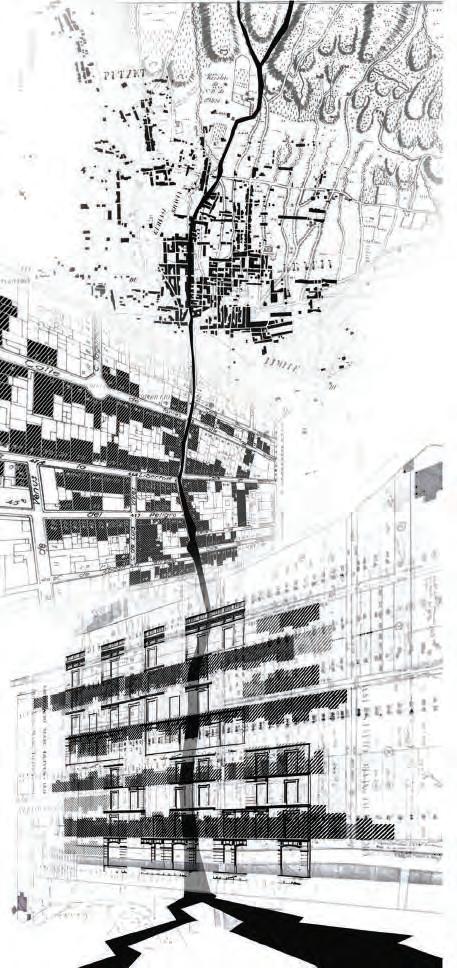

As a result of my visits to Mexico my thesis evolved into a comprehensive study of the socio political and cultural influences upon the urbanization issue. Moreover, the experience itself certainly changed my life. The vast cultural differences between my Midwest upbringing and the massive amount of poverty and radically different lifestyle of these urban populations changed the way I would see people for the rest of my life. I began seeing the world from a perspective of: “how can any of us ever complain about what we have and the way we live and conduct our lives”. I began to appreciate life more by working to understand these other lifestyles through my thesis. These problems, urbanization and housing issues, are still prominent today as well.

It changed my perspective knowing you can’t simply impose change to just one entity in an equation and necessarily expect a different result. You have to look at all the constituents – and maybe – reformulate the whole composition.

I began recognizing and remembering people above all else. I would be able to remember the names of people involved with my research, travels, and work and will continue to remember them for the rest of my life. There is an inherent value in letting people into your life and remembering their stories and connections.

Transferable Skills

RR: Do you think the dimensions such as teaching, practice, and family are more interdisciplinary? Do you learn from them collectively, or is it more of a balancing act of delineating different components of your life?

It’s easy to become engrossed in completing one

specific task. This can happen at any point of our journey. It can be completing a class project, meeting a business deadline, resolving an issue over the installation of a building component, the list is endless. In my first stages of building and designing for clients I was surely overloaded with these goal oriented tendencies. While in graduate school I found work with a skilled German carpenter who taught me a craft of many fabrication details. It was evident that there were skills which transferred from one craft to another. I would say that an ability to see a new problem with clarity and understanding emerged from my carpentry experience. As I began my practice several years into this experience, I began to see larger rhythms of the way projects flowed from their beginning to end. I think looking for patterns and rhythms is something as designers we simply do.

20

“

Every journey begins with a thought… with a dream… an idea which transforms itself in the moments of travel.”

Larger rhythms of projects and the lifestyle I was learning directly coincided with perception of space that I learned in schooling and a strong work ethic. I wanted to know everything there was to know about showing things graphically on paper – and allowing to show things and perceive the world in alternative ways. With students today, we don’t always realize that what occurs in the professional world doesn’t necessarily pertain to what we do in education. We are trained for a lot more in life than just architecture. We also learn a lot more, specifically, from the people around us than the coursework. Noting that I am not taking anything away from the importance of education and coursework, it is simply a testament to the types of people you can come across in the world, and at the University of Illinois, that we are able to learn more from the people around us. My personal experiences with friends, family, and strangers along my life journey has contributed to how I think about architecture and approach my studies, but it also contributes in a more prominent role to how I think about life.

More generally speaking, underscoring all of what you asked here of balance either compartmentalized entities versus collective- I see them as a collective. For example, some of the important lessons which I have employed in my practice we certainly birthed out of the context of raising my children. There is a world view in what I’m saying, a life paradigm. It is the way we conduct life, the way we think about ourselves and about others. I think when we consider life in these terms we are able to bring expertise and guidance into new and varied situations despite their complexities.

Thoroughness

RR: Do you take the principle of following through with

22

23

“ The earth doesn’t demand our attention; yet when we give it such, it commands our gaze and compels our reason.”

your small-scale projects? Because the project, space, lifestyle is meant to be sustained for a while after your part in it -

TL: For me, the practice of (dedication to) thoroughness provides the essential framework to the notions of sustainability.

This process begins with meeting a client an understanding what they hold as priorities, values, and project objectives. The clients themselves should be the mechanism for how we define a particular project’s parameters and objectives. The craft of a good

architectural design starts by listening and listening carefully to each exchange of information. When we write and design around this premise everything become quite intimate and real for the client.

Thoroughness should be evident in every consideration when it comes to architectural design and building projects. In running a residential design build practice nothing is left for speculation. You have to be a problem solver and have an awareness of the various disciplines which contribute to obtaining someone’s objectives. There are many facets to architectural practice other than simply designing an architectural product. When you

24

move a line on a design sketch or computer image you should fully understand how it changes the architecture, how it affects the building performance, how its influences the fabrication

Just as there is a dedication to problem solving when it comes to architectural design, there is an equal devotion to thoroughness in practice. I can’t think of a project where I wasn’t called upon to resolve conflict, or resolve the numerous difficulties of fabrication in the build process. Many hours of my practice are spent in product research and project planning, probably more than design time. The hours spent in fabrication on projects

sites probably trumps all of these endeavors with respect to time and energy. I’m not sure if it’s simply a creative tendency, or just a mechanism to keep afloat with a busy life, but for me all of these components fortunately seem to weave together in a memorable and clear rhythm of organization and intent. My take home message for others would be that when we strive for clarity and resolutions throughout the entire process we elevate the project as a whole; from my perspective, this is the chief characteristic of a sustainable project.

25

“

Just as there is a dedication to problem solving when it comes to architectural design, there is an equal devotion to thoroughness in practice... when we strive for clarity and resolutions throughout the entire process we elevate the project as a whole; from my perspective, this is the chief characteristic of a sustainable project.”

Nature

“

-

Process

RR: It’s a matter of perspective though, isn’t it? You learn from education, take that knowledge to professional practice and learn there to teach new knowledge to your students – it becomes cyclical in nature. I would imagine it creates an all-encompassing view, and cultivates for a better vision of the future, one in which you play an active role in.

~ moments on the journey matter ~

TL: I believe it is very interdisciplinary, very intertwined. Ultimately we do produce architecture; we give a client a place that they identify with as their own. So losing sight of the product would be a mistake. However, cultivating that architectural product has everything to do with the process.

Recapping, the interdisciplinary or cyclical nature of what you mentioned, ongoing success is more about process than product. There is a product which a client receives from me, but if you ask them what they remember most, I’m sure they would reflect in detail upon the process they have undergone. They remember the moment where they engaged in the idea of “what their home could be.” Taking people through this long and exhaustive process of design and building a home is quite a task. Not many clients would do it if they were handed all the topics and information for discussion at one time. It’s a long journey and it takes someone to help clients navigate through it. I think this is perhaps

Nature brings clarity ”

Our industry’s approach to the digital and delivery of data in the built environment needs to stop looking like a spreadsheet and more like prototyping with sensors.

27

what I enjoy most about what I do. When you hear a client’s ideas for the very first time it immediately conveys a sense of project trajectory. It promotes questions about how this project might be built, how much it might cost, how much time and energy a client will need to invest in order to make it successful. In order for me to design well, I believe it’s accurate to say that I am truly a part of my clients’ life. After 35 years, I see clients who are my friends. They often reflect upon the things they remember and that are important to them about our projects. I have watched clients raise families in these homes.

I can admit that because the investment is so intimate at this scale of design it is hard to clarify the point when a project is truly considered done. This is something that takes some of us many years to clarify for ourselves.

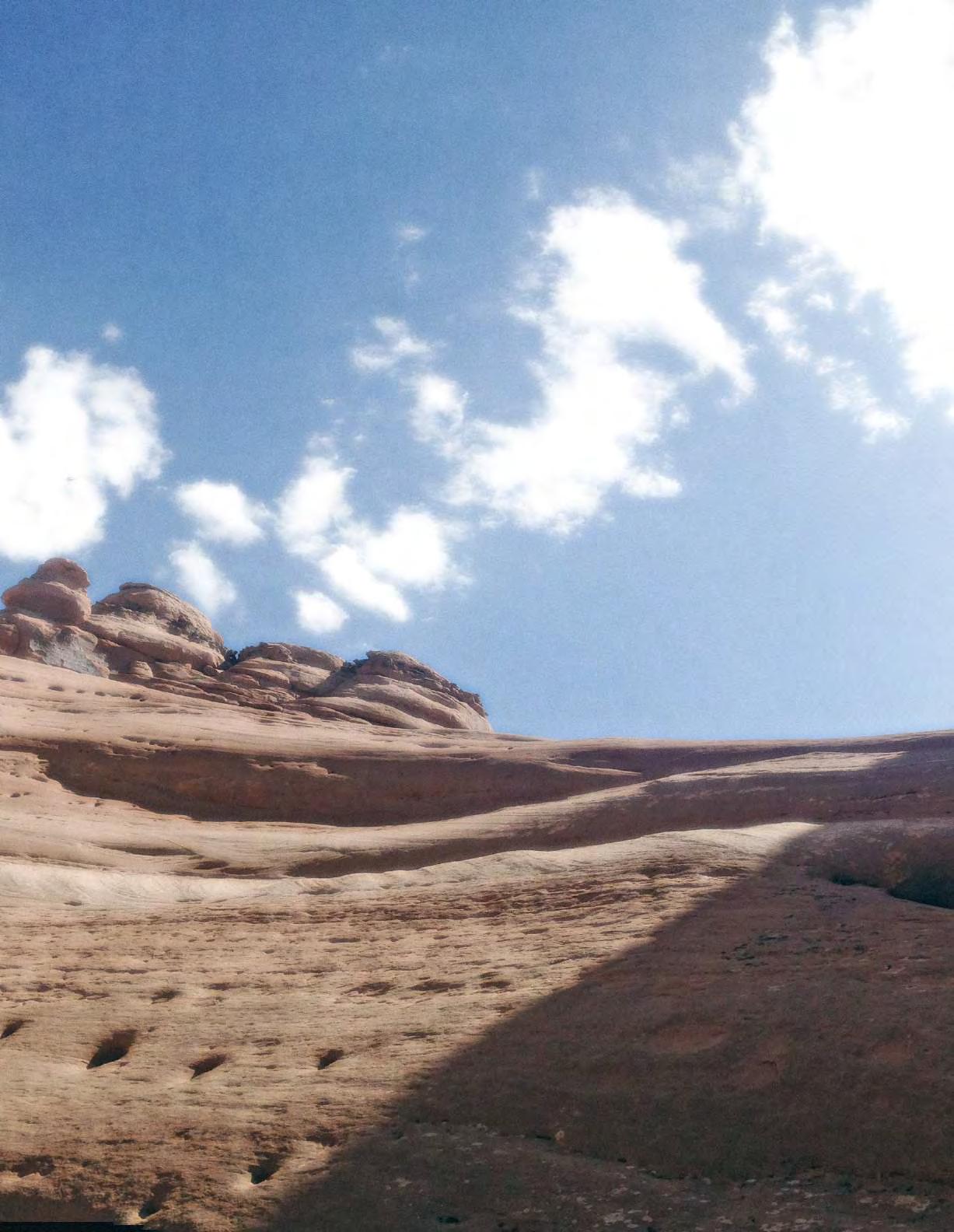

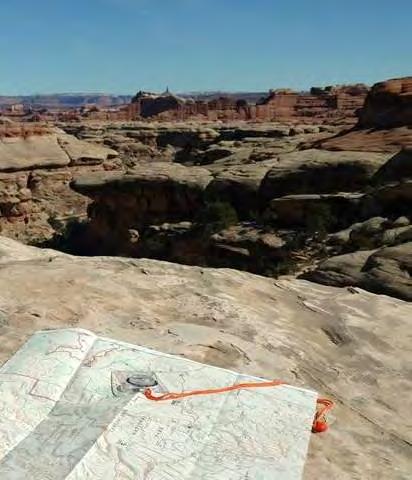

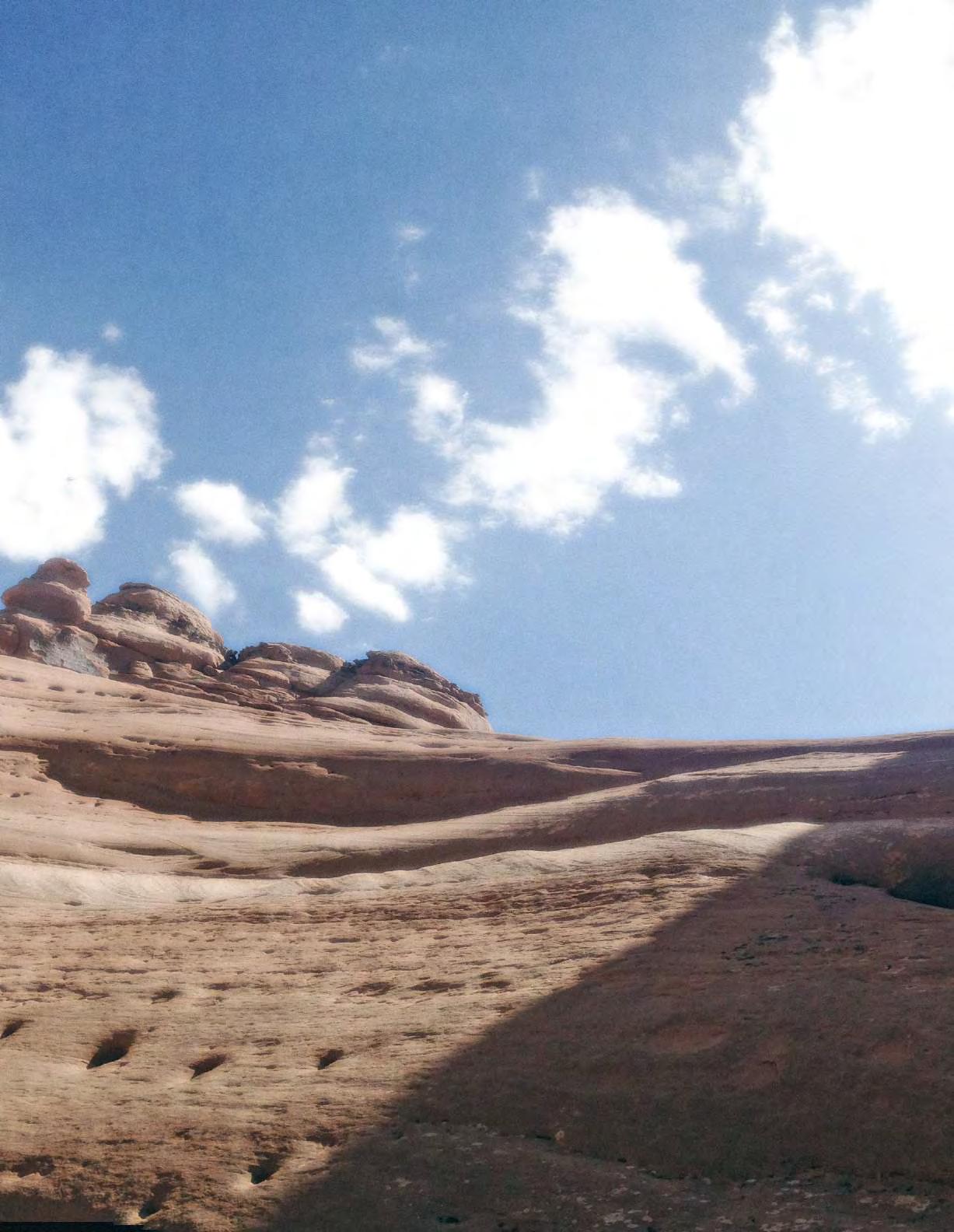

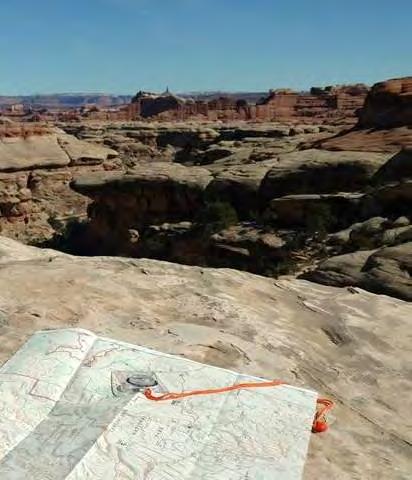

Regarding process, in traveling, it is important to me. You appreciate process more. Understanding where you are at in a journey is just as important as the destination. Just like in design, everyone thinks about some end result, reaching some summit, and that there is an epiphany from it vantage point. Hopefully, people can dial back from that belief system and realize that clarity and insight can happen at any given step along the journey. This happens at a moment of fatigue, at a moment of personal breakthrough, it happens when the people alongside of you need help. It is embedded in one hundred different directions we take. Traveling reminds me of that. And it is a truly beautiful way to travel through life. There is a true treasure in finding others on the path that share these moments together and elevate each other’s journeys. To experience life rhythm at this scale makes me quite grateful.

28

“Pathways, embrace the journey”

RR: Well this something you sell. It is more than a product simply because your end product includes a very diligent and all-encompassing process. That is not necessarily something many people do.

TL: It’s hard to categorize what I do as a commodity or something that I sell. I’ve always felt that professional practice was just something that I did amongst all the other tasks of life. Wanting to create and create for others is something I have always done intuitively. Perhaps I feel most comfortable thinking of what I do as an exchange. We learn invaluable lessons related to working with clients. I think it’s imperative to be other focused in the midst of our journeys. We often find what we need when we are looking to help or guide others.

To be honest when it comes to teaching, I believed it would enrich my life to teach, but I was also surprised by the value it brought to the way I approached business. I believe it has been the source of tremendous refinements. Imagine coming to a studio and being challenged to teach students, in 14 weeks, what I have gained in a thirty year career. Teaching over the last few years has given me a clearer voice with my clients in guiding them through the potentially very complex world of design build projects. In turn, it has given me a clearer voice with my students. I am much more deliberate with what is necessary at the given moment. Perhaps all of this has value for me because of the belief I hold in process. The years of practice have helped me intuit a project’s potential success or difficulties, but this insight doesn’t give me a magic solution for students or clients; it merely reaffirms the necessity of the journey and many steps required in obtaining that goal. I think my clients of the last few years are getting a better experience and product than some of those I have served for the prior 30 years. I feel like my architecture and my practice are both in a much better place today and teaching has played a big role in that.

Distillations

RR: Are there other ongoing experiences which have expanded your perspective or caused you to reconsider your approach to design in new or alternative ways?

TL: Invariably communication has to become distilled. Teaching others has helped me to see how I think about the design process in that very manner. It has also helpedmetoappreciatethevalueinthemomentsalong the design path. I like to keep viewing architecture and

30

practice from a broader perspective other than the ways which I have been accustomed to approaching it. We measure and measure for exactness and detail, yet when it comes to the vastness of everything around us, we truly know so little about time and measuring. I spend a significant amount of time getting myself remote on trips into nature. There is a perspective gained in nature, out in the natural landscape. I think that my life and my thoughts become clearer with each experience of traveling into the wilderness.

This vast landscape provides an undeniable language of rhythms. When we are able to engage rhythms at

that vast scale it invariably alters our understanding of ourselves. It provides an opportunity of exploration and discover of things we have as of yet to consider, let along understand.

31

Compression and emergence

...in this journey we call life, we are all variations of the same reality...

Compressed...

Expressed - within a veil, Digressed - to an elemental tale, Impressed- with double vision, Suppressed - in time and limitation...

Emerging...

Ascending - to heights within, Transforming - new life begins, Perceiving - another reality, Unfolding - life’s deep mystery...

...we emerge as we do; because we have taken this journey we call life....

32

- Tom Loew

(11) Delicate Arch, Moab, Utah (2016) (12) The Druid, Canyonlands, Utah (2017)

(15) Devil’s Garden Primitive Loop, Moab, Utah (2015) (16) Spooky Gulch, Escalante, Utah (2018)

(17) Hole in the Rock, Lake Powell, Utah (2018)

(21) Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, Mexico (1985)

(21) Villa Park, Illinois (1976)

(21) Mount Rainier, Washington (2003)

Journey Through Photos

Photos (In Order of Page)

(21) Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, Mexico (1985)

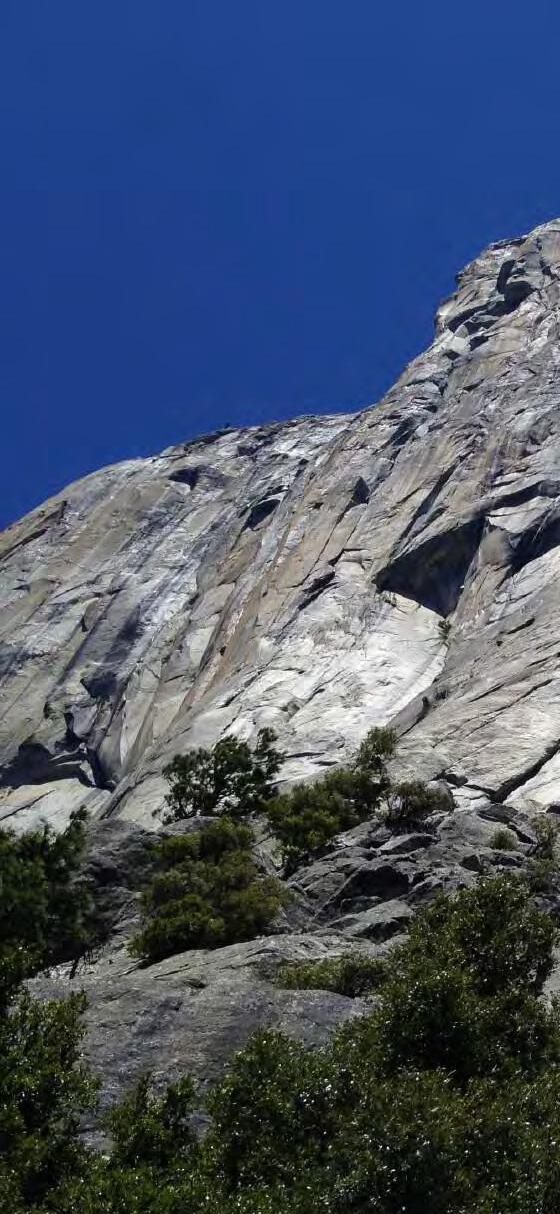

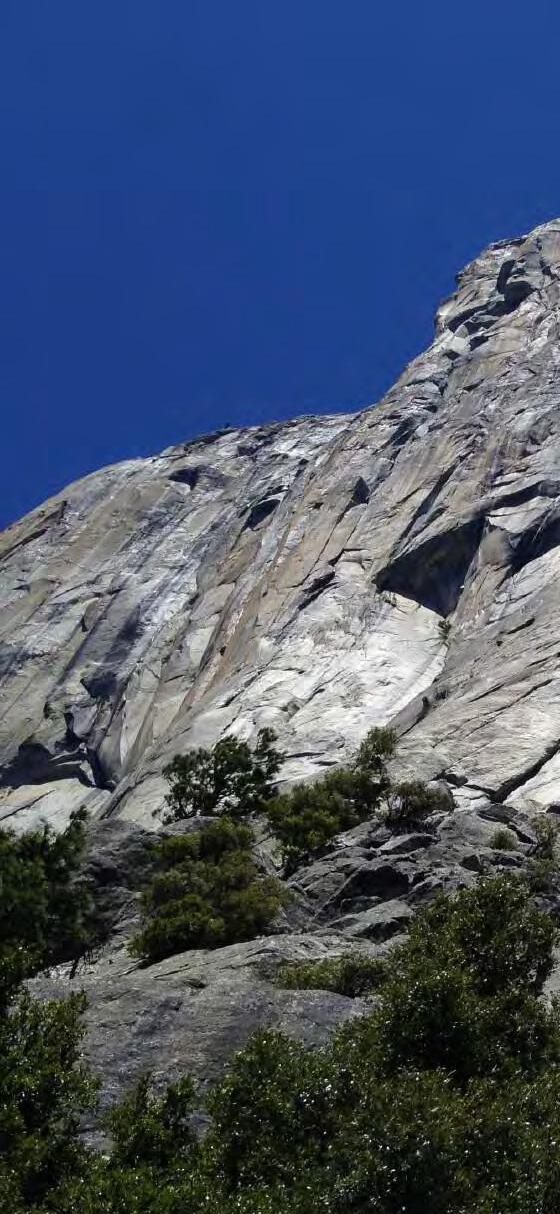

(23) El Capitan, Yosemite, California (2016)

(24) White Heath, Illinois (2017)

(26) Half Dome, Yosemite, California (2016)

(29) Urbana, Illinois (2019)

(29) White Heath, Illinois (2017)

(29) Peek-A-Boo Slot Canyon, Escalante, Utah (2018)

(31) The Needles District, Canyonlands, Utah (2017)

33

Society, Economy, & the An Interview with Christina Bollo

the

Bollo

Environment

36

Christina Bollo

Architect | Educator

Christina Bollo is an assistant professor in the Health and Wellbeing focus area. Professor Bollo’s research and teaching focus on the social, economic and environmental ramifications of housing design, and the manifestation of policy in the built environment. Her current research investigates social interactions in the shared spaces of permanent supportive housing projects, commonly known as “Housing First.” She teaches an active-learning course in “Global Health and Architecture” (ARCH 321), and graduate-level design studios, where her close connections with non-profit housing developers and architects give students exposure to the affordable housing industry. She is a licensed architect in Washington State.

37

Ricker Report: What is the reason you chose to pursue architecture?

Christina Bollo: Growing up, I delivered food in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood by creating bags of groceries from donated surplus food. I carried them to people who were homebound, usually in subsidized apartment buildings. I learned that while a rudimentary housing safety net did exist in Chicago, especially for seniors and people with disabilities, the housing itself was in very bad shape and difficult to live in. I realized that it was not well designed. That brought me to architecture.

at the University of British Columbia and lived in Vancouver, a place of awe-inspiring beauty. The cultural distinctions between Canada and the United States are subtle to the casual visitor; as a resident, though, I was intrigued by differences in health care, relationships with indigenous communities, and commitment to the natural environment. When I travel, I love being out of my cultural comfort zone, even in small ways, and I love being immersed in natural and architectural beauty. Mexico City is my favorite place to visit for these reasons. And the food is incredible, as well.

RR: How have your degrees and education path influenced you today?

CB: My architecture career started more slowly than most students in our program at U of I. Becoming an architect wasn’t part of my plan when I started college at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. By the time I was a junior, I was quite sure I would apply for a “Track 3” style Masters of Architecture program, so I chose to major in English Literature to gain a strong liberal arts foundation. I attended the University of Oregon because they have a very large Track 3 program with opportunities for research and teaching, as well as a strong focus on environmental sustainability, an essential value instilled in me by my family. I never expected to pursue a PhD, but after 10 years of practice in Oakland and Seattle, I needed to understand how our design decisions impact residents’ quality of life. I returned to Oregon and was a member of the first class of their PhD in Sustainable Architecture.

RR: What architect most influences your work and/or your work habits?

CB: Herman Herzberger has been my greatest and most consistent influence. His writing helped me to develop my ethic that architecture is a social art; buildings are vessels for people and their activities. I made a pilgrimage to see his work in person after I finished my M.Arch. What a joy to watch children play at his Montessori school; to see people move in and out of his Borneo housing; to sketch his elegant detailing of humble materials. His work also influenced me because he is very serious about the section of the building and the social opportunities that a well-designed section can create.

RR: What skill (or set of skills) has served you best in your architectural career?

RR: Where are the places you have travelled? For work, living, or presentations/lectures?

CB: After finishing the PhD, I worked as a researcher

CB: Listening, looking, and always documenting. I think that’s all it is. And these are skills, not talents. With practice and the help of many mentors I was able to develop those skills, both in school and in the profession. I learned how to look at buildings and understand how they’re put together, to see the core design principle, just by looking at two materials coming together.

38

39

40

LISTEN | LOOK | DOCUMENT

RR: Where do you see yourself five years from now? 20?

CB: In five years, I want to be doing exactly what I am doing right now, just better and more. Connecting studio teaching to my research agenda encourages students to be on the leading edge of housing design, and keeps me focused. In twenty years, I’d like to be leading a housing research institute, embedded in a university, so housing developers and architects can benefit from research, and students can contribute to the profession in a meaningful way. This could come together through funded studios that explore complex housing programs, or even through primary research projects that investigate wellbeing in existing housing.

in 1995) for Environment, Economy and Ethics (or Society). Sometimes, sustainability is just the Environmental leg of the stool, or, even worse, sustainability can be short-hand for Green Building. One problem is that the architect’s intervention almost always degrades the environment. But socially, our interventions can be sustainable, and can even be regenerative, creating more opportunities for human health and well-being. As a social scientist, economics has been important to my research, and it is essential to sustainability. We can imagine great spaces, but if we can’t make the economic equation work, we’re not designing sustainably. And I’m not advocating for cheaper buildings: I’m advocating for buildings that are worth it.

RR: Your research and teaching focuses on the social, economic, and environmental facets of housing design. Can you tell us a bit more about these components of the world?

CB: I subscribe to a definition of holistic sustainability sometimes called the “three Es” (coined by Goodland

RR: What past professional work have you worked on/completed relative to housing, sustainability, and health and wellbeing?

CB: The project that most exemplifies my ethos around sustainability and health is Kenyon House, which I designed with SMR Architects in Seattle. Kenyon House

41

“

”

provides studio apartments for 18 formerly homeless people with HIV/AIDS and other physical and mental health challenges. Because of this, the client and I were very motivated to create an exceptionally healthy living environment. We used the LEED for Homes checklist, and focused on the criteria that had clear health outcomes. We prioritized indoor air quality and thermal comfort. Interestingly, some of the things we did to create an energy efficient building, such as an air barrier and insulation between apartments, also had wellbeing impacts, such as decreased odor and sound transmission. We achieved LEED Platinum certification, one of the first subsidized housing projects to do so. The second edition of the Green Studio Handbook has a case study of this building, if readers are interested in learning more about the project and the development process.

RR: How have you been able to contribute to practice from the research you have done?

RR: Can you tell us more about your own research, specifically how you’ve seen social interactions within housing affected by architecture?

CB: My current research project investigates the common area spaces in permanent supportive housing, buildings similar to Kenyon, that provide apartments for people who have experienced chronic homelessness. Social workers have advocated for large allocations of common areas in these buildings, but little is known how the residents use this space. So far, we have inventoried the designs of twelve supportive housing buildings and used space syntax analysis to uncover typical patterns in their designs and layouts. Our next step is to visit the buildings, and, in the most unobtrusive manner possible, watch how the residents read these patterns and how the design affects their use of the space. We are still searching for the right metric so we can report back to architects and housing providers and they can more effectively design these places.

CB: Evidence based design is essential, but it can be hard for practicing architects to conduct primary, or even secondary, research. My research partner, Amanda Donofrio, is a practicing architect who designs all types of affordable housing. Through our partnership, I provide Amanda the scholarly sources she needs to further her design, and together we pursue research projects that produce new knowledge of the profession. I am committed to conducting useful research, to produce findings that can help practicing architects make the case to their clients for better design. This includes working together from the beginning to generate research questions, find the right metrics and, very importantly, disseminate the research so that it is accessible to architects.

RR: You also have a small practice focusing on low-rise, deep-green residential development. Could you tell us more about this?

CB: After I finished my PhD, I wanted to maintain a substantive connection to practice to stay up-todate on materials and methods, and because I love designing. Adrienne Gerig-Heyerly and I started

42

43

Design Response after she received several house commissions. We are committed to extreme envelope efficiency and responsible use of resources and we are very picky about which projects we pursue. Even though Design Response is a relatively small component of my professional life, it is outsized in its importance to my teaching. When I chose recent work for the gallery last fall, I wanted to share work with students that was accessible in its size and scope and to demonstrate the connections between drawing and complete building.

RR: Is there any advice that you would give to women who are currently entering the field of Architecture?

CB: When I go to lectures, when I teach studio, when I read essays from ARCH 321, I see students of all genders committed to fairness and equity. If they maintain this ethos as they enter the profession, this

generation of Illinois grads will have great success in dismantling institutional sexism in architecture. I have two mantras: first, stick together; and second, seek mentorship, both up and down. Sticking together can help daylight discrimination: sharing uncomfortable incidents with friends, even if we make the choice not to report to a higher authority, makes us resilient. I’ve noticed that many of my students share salary offers with each other, which is a powerful way to stick together. I urge students to seek good mentors early in their careers, so they are available when they need them. For example, starting a family affects women’s careers differently than men and strong mentorship can help women plan: find parents in your firm and ask them how they navigated this and find parents in other firms to see how policies differ. Transparency is essential if we want to change the many biases in the profession.

44

45

“

As a social scientist, economics has been important to my research, and it is essential to sustainability. We can imagine great spaces, but if we can’t make the economic equation work, we’re not designing sustainably. And I’m not advocating for cheaper buildings: I’m advocating for buildings that are worth it.”

Family, Fabrication, and An Interview with Lowell Miller An Interview

with Lowell Miller

and Fellowship

ABOUT LOWELL:

Fabrication Coordinator Lowell Miller is a man who has worn many hats over his lifetime. He holds a Bachelor of Liberal Arts and Sciences from the University of Illinois in Urbana - Champaign, along with an Associate Degree from Parkland College. He was also previously the retail store manager for the CU Woodshop and School in Champaign. Since 2011 he has been the sole proprietor of Miller Woodworks, his own personal fabrication company that produces standalone furniture pieces and the Mod Dock acoustic amplifier.

Joining the University of Illinois faculty in 2016 as the Interim Fabrication Coordinator, he was appointed to the position officially the next year. Alongside heading our woodshop in the Architecture Annex, Lowell also leads the Root to Roof Project , an initiative to encourage, practice, and educate others about urban wood harvesting. The pieces produced from the Root to Roof Project can be seen throughout the Architecture campus, including benches and the ‘Untethered’ structure seen adjacent to Temple Buell Hall. Lowell took some time to discuss with us his thoughts about fabrication, how his life affects his work, and the success of Root to Roof:

49

Ricker Report: How does your family inspire your work now?

Lowell Miller: Inspiration comes from many sources. If I were to pinpoint family that inspires me, I would have to start with my wife. She is a career educator, but her hobbies include drawing, painting, knitting, gardening, and photography. She is the reason that I really got into woodworking and fabrication as her support and confidence helped me out considerably. I also have many other family members and friends who create, and their work inspires me to do the best work I can, when and while I can.

problem solving. Though I have those underlying skill sets, I admit that necessity of being a new homeowner with more time than money is how fabrication became a lifestyle. As my confidence in what I refurbished, designed, built, and constructed grew, so did my desire for a career that encompassed fabrication and design. I also had jobs in lighting design and layout, construction, and woodworking that led me down the path of fabrication.

RR: What made you decide to pursue fabrication as a career, or even as a lifestyle?

LM: I am naturally mechanically inclined, and I love

RR: What is the most satisfying piece of work that you have ever made? What made it so loved?

LM: The most satisfying piece changes by the day, month, and year. Honestly, I am most satisfied with a piece as soon as it is completed. That said, I then begin the process of trying to make that piece better, so the satisfaction is fleeting. My most consistently satisfying piece is my Mod Dock, which is an acoustic amplifier for smart phones. I

50

“

I firmly believe that skill acquisition leads to flexibility, adaptability, resilience, and a strong problem-solving skill set. Architects occupy an interesting intersection of design that, when coupled with problem solving skills, enables those individuals to dive into many different mediums and find a career there.”

have sold and shipped this piece all over the world. The Mod Dock (seen left) is an original design that helped me to really become the woodworker that I am today.

RR: You are the creator of the Root to Roof Project . What was your inspiration in creating Root to Roof and where do you see it in five years?

LM: I was inspired to create Root to Roof for many reasons, and as all inspiration tends to, they happened to come together at around the same time. The main reason for Root to Roof is that there is an enormous amount of urban lumber that gets mulched or turned into firewood,

52

which is not very sustainable. This material could instead be used in a way that would keep it out of the carbon cycle. The best way to do that is to make it into usable product. What better place to make usable product than in the ISoA!

I see Root to Roof as an ever-evolving project with a keen focus on design build projects that benefit society. The goal of this project is to use urban lumber to build sustainable housing for those that are homeless or in transition. As a top tier institution, we at the university, and especially in the ISoA, are in an excellent position to think big and develop projects and programs that benefit our fellow man. The Rural Studio has the 20K

House program, why can’t we have a 10K tiny house sustainably made from urban lumber? So, in five years I see Root to Roof as a not-for-profit, in the vein of Habitat for Humanity, that builds tiny homes for those in need.

RR: What has been the most interesting experience in working on Root to Roof ?

LM: The most interesting part of working on Root to Roof is that it involves networking and outreach in ways that I hadn’t thought about at its conception. The program also requires skill acquisition like learning how to use a chainsaw, how to mill logs for specific purposes,

53

“

I am naturally mechanically inclined, and I love problem solving. Though I have those underlying skill sets, I admit that necessity of being a new homeowner with more time than money is how fabrication became a lifestyle .”

how to dry the logs to get usable material, on the fly problem solving, videography, event planning, project management, and improvisation when and where necessary to complete the task at hand.

To date though, the most interesting experience is working with thoughtful, curious, and hardworking students. I try to learn as much from students as I hope that I impart to them. The ‘Untethered’ structure encompasses all of that. I am exceptionally proud of the students that worked on that project and I am so glad that I was able to be a part of it.

RR: What is one thing that you hope anyone who has worked on Root to Roof has taken out of the experience?

LM: My goal is to impart knowledge and growth that allows anyone that works in our shops or in Root to Roof to be well suited to life after college. I firmly believe that skill acquisition leads to flexibility, adaptability, resilience, and a strong problem-solving skill set. Architects occupy an interesting intersection of design that, when coupled with problem solving skills, enables those individuals to dive into many different mediums and find a career there. There are so many people that start in architecture and pursue that career path and there are many that start in architecture and go into careers in the culinary arts, industrial design, furniture making, print and digital media, etc. Architecture can be a grand buffet of ideas if one is curious and dedicated enough to dive in.

RR: If there is one tool that you were forced to use in every project that you work on from here on out, what would it be?

LM: A pencil. I’ll let you draw your own conclusions.

54

Women’s Reunion & Symposium

September 26 -28, 2019

“A symposium, a reunion, and an exhibit”

Information: The School of Architecture at the University of Illinois at UrbanaChampaign invites you to join us on September 26-28, 2019 for a reunion and symposium for our alumnae. This two-day symposium will examine, celebrate, and recognize our alumnae through speakers, work sessions, and informal gatherings.

It is also a reunion to share stories, journeys, and work, inside architecture and out. Expand your network by connecting with our community of over 2400 women graduates around the world.

We are additionally excited to announce an exhibit featuring the work and stories of our alumnae at the Krannert Art Museum, which will open during the Illinois School of Architecture Women’s Reunion & Symposium and continue through October 12, 2019.

We look forward to you joining us in September!

Marci Uihlein & Sara Bartumeus, Organizers

For more information contact: arch-women@illinois.edu

Website: https://arch.illinois.edu/arch-womens-symposium

RR: The symposium is planned for September 26 – 28, 2019. Could you explain your vision for the symposium?

A: The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign has long been a pioneering program. Mary Louisa Page, for example, became the first woman to earn an architecture degree in the United States in 1878, just a decade after the University of Illinois offered its first architecture course in 1868. Today, we have 2400+ women graduates out impacting the world. These alumnae, inside architecture and out, are doing all types of wonderful things. We wanted to welcome these graduate back to share their stories, to connect to each other, and to bring their work and energy to the School of Architecture.

RR: Would you like to further explain what is planned for the symposium?

A: The event will include speakers, intergenerational panels, and an exhibit opening. We were pleased to be able to curate an exhibit at the Krannert Art Museum featuring the work of our graduates. Inclusive and declarative, this exhibition will visualize the diversity and depth of alumnae work in a collective display. We have sent out requests for submission with all work welcomed and continue to look for contributions.. This exhibition reveals both a growing and a significant presence of women in the profession, despite persistent challenges, and celebrates their remarkable accomplishments. Additionally, during the two-day event, there will opportunities to interact with the students, see the School today, and share meals with each other.

only 18% of licensed architects in the United States and have similar percentages at the top roles in architectural firms. Progress towards gender equity in architectural education is being made, with women currently comprising over 40% of architecture graduates. Despite these improvements, however, women still have fewer career opportunities, hold fewer leadership positions, and earn less recognition for their work. Women remain underrepresented as do people of color. The research has found that there are a number of challenges for women in the profession including lack of role models and mentoring, women are less likely to receive a promotion, and unequal compensation for their work. In terms of globally, each country has its own issues for gender and we are not able to comment on this directly.

RR: How have your experiences, as a woman in architecture/engineering, changed over the years?

RR: What is your opinion about the view of women in architecture in the United States? Does this opinion change on the global scale?

A: Statistics by the American Institute of Architects and other organizations tell us that women comprise

A: Today, we all believe that change is being made, however slowly that may be. Anecdotal evidence includes two recent recognitions: Carol Ross Barney receiving the Illinois Medal (2019), the highest honor for the School and the first woman to do so. This is, of course, after she had received the AIA Illinois Gold Medal (2015) and an AIA Chicago Lifetime Achievement (2017) awards. Jeanne Gang, in addition to her many acknowledgments, was named by Time Magazine as among the 100 most influential people in 2019. This recognition shows Ms. Gang’s growing influence outside of the architectural field. These are but two recent stories among the many that our alumnae are creating. However, change is still needed. When Carol Ross Barney graduated, she was one of three women in her graduating class, and even through there are many more now, barriers remain. We write today as practitioners that have become educators. While there has been much discussion around women in the field, there needs to be some examination of women in architectural education. For example, women faculty

59

in ISoA make up only 20% of the faculty, and there have only been three women who were promoted to “Full Professor” in the School’s 146-year history. While students now have the opportunity to be taught design by a women faculty member, it is not guaranteed that everyone will do so. Challenges remain in academia as well.

RR: Are there any particular stories you would like to share?

A: Many women practitioners and educators have stories. We are hoping that this event will give our graduates a chance to share these stories, learn from each other, and to find or provide some mentoring. The event was designed to have formal opportunities for discussion and many moments for informal dialogue. We hope that everyone will meet someone from a different generation or location and be able to take something back with them – advice, new insights, and even new friendships.

RR: Unfortunately, there are still people in the industry who undervalue work done by women. In your opinion, how can these actions be combatted?

A: Two sources can provide insights here – Equity by Design and the AIA’s Guides for Equitable Practice . Both efforts have challenged the field of architecture to find new “best practices” within architectural firms. For instance in hiring, some firms have blind application reviews, while others have developed clear and agreed upon hiring criteria. As equitable compensation remains an issue, pay audits help a firm understand how salaries are distributed as points of data and then these can be examined under a set of firm’s established criteria. Establishing a diverse compensation committee within a firm is another option. Clear and accessible promotion criteria helps employees understand the firm’s leadership development strategy. Similarly, it is recommended that employees are evaluated on a regular basis and receive ongoing feedback. There are a good deal of tangible actions that can create a culture within a firm that is more welcoming and supportive of women and people of color.

60 “

This exhibition reveals both a growing and a significant presence of women in the profession, despite persistent challenges, and celebrates their remarkable accomplishments.”

RR: As a highly regarded professor, what are values you would like to continue to teach/bring to your courses at the School of Architecture?

A: Thank you for the compliment. We expect that our answers would be very similar to our colleagues, male and female. We bring a desire for our students to learn, be challenged, think critically, and be successful in whatever path they chose. We hope to give our students the best foundation possible for a lifetime of learning and the ability to begin to address the needs of our larger societies.

RR: Any closing thoughts or details?

A: We are very excited to welcome our alumnae back to Illinois to participate in this multifaceted event!

With the exhibition, Revealing Presence: Women in Architecture at the University of Illinois (1874 - 2019) , at Krannert Art Museum, we want to show and celebrate the impact of our alumnae work and be declarative about the role of women in architecture. Women’s work often does not find itself in main publications and exhibitions, rather it remains somehow hidden, with its authorship unknown, unrevealed. The exhibition, intentionally inclusive of the breadth and depth of our alumnae work, will show the diversity of their architecture, the scale of the work and its worldwide imprint on the built environment in a collective display. Historical data and architectural work will be displayed along a timeline, reflecting Illinois as a pioneer and also as a mirror of the imbalance growth between women and men in education and practice.

own stories. Bringing visibility to issues for women in architecture and beyond we aim to make some change together. Several keynote speakers and nine panelists, soon to be announced, represent and will be sharing a myriad of trajectories of our alumnae in the profession, aligned fields, or elsewhere. Through different formats -- with live interviews and Q&A sessions between students and alumnae -- we aim to have an intergenerational panorama and also a fertile discussion. Examining past and present obstacles, challenges and accomplishments, will help us sketch, and hopefully build, bridges towards a more equitable future.

Besides all of the above, the reunion includes informal opportunities for exchange, we want our alumnae to share memories of their time at Illinois and to update and expand their networks. The event will take place in several university locations to give alumnae a chance to revisit favorite old building and see new ones. Optional tours will be held before and after the event as well.

We only need YOU - Come and join us September 2628!

(By the way, if you have not received our communications it is because the University does not have your current contact information. Please reach out to us at arch-women@illinois.edu!)

With the symposium, we want to hear our alumnae voices, to get to know more about the career paths they have traced inside or outside architecture, to hear how their education in architecture has shaped their views and work, and to learn from their very

61

ARCH 232

Marci S. Uihlein, Associate Professor

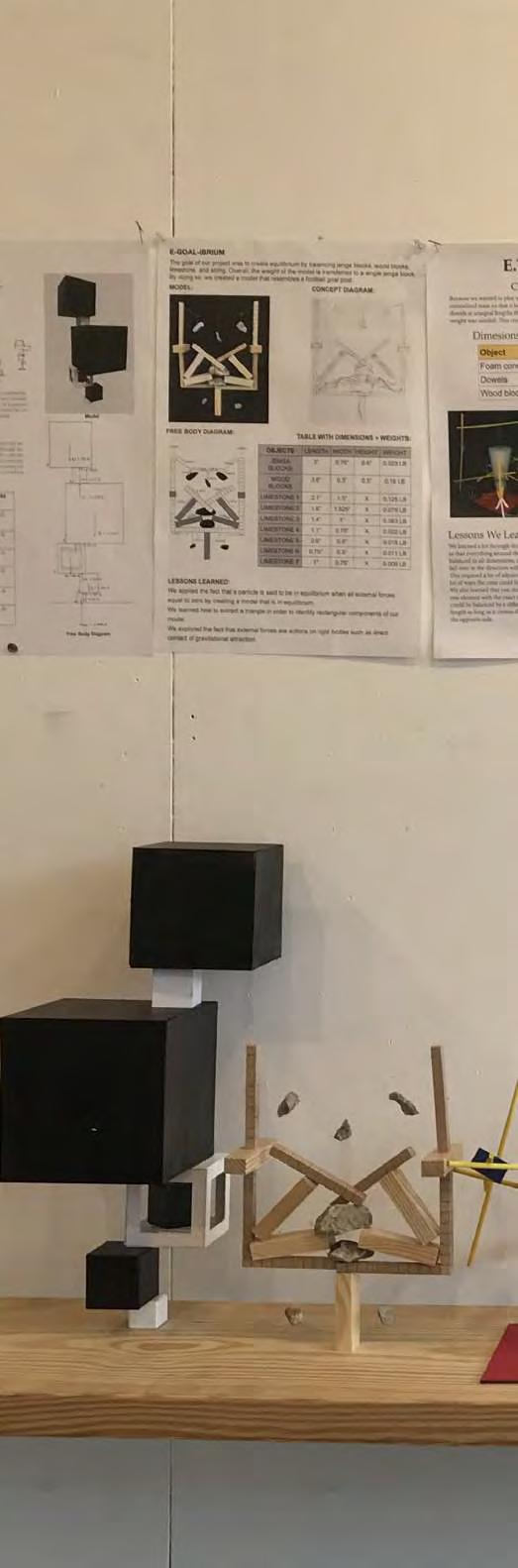

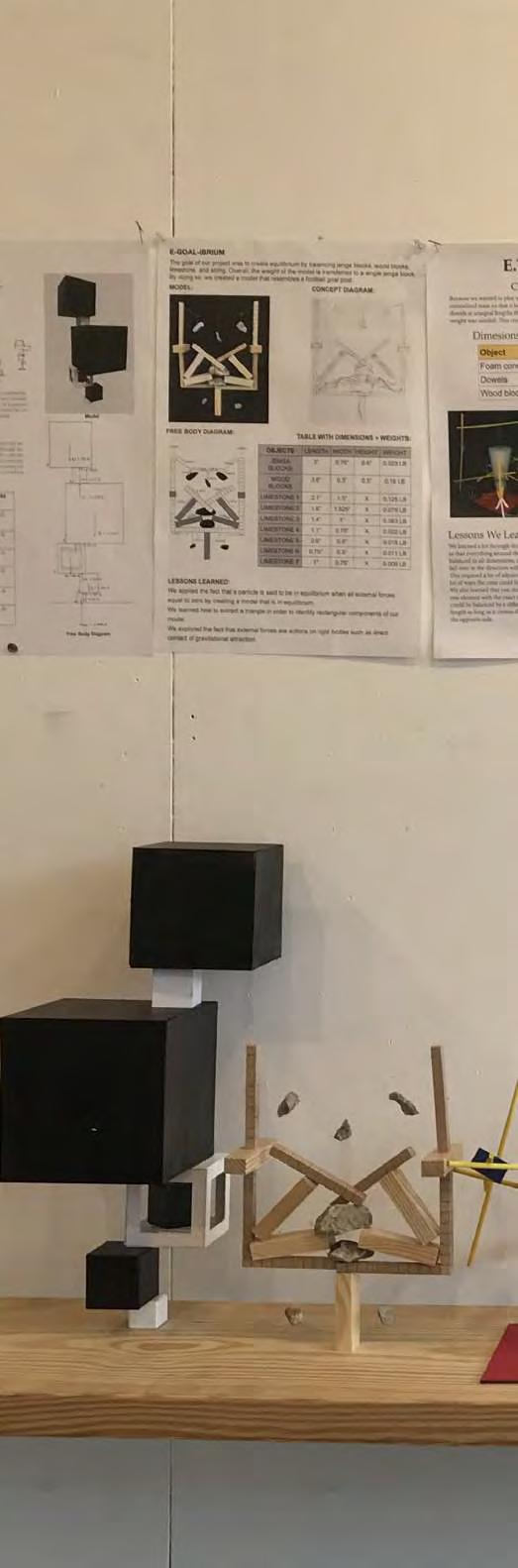

Introduction: As part of our series of classes the School of Architecture’s new curriculum, ARCH 232 is presented here. It is a required course for sophomores in the second year of the undergraduate program. This Spring (2019) was the first time the course was offered. This feature provides an inside look of some of the course group projects.

Course description: This is a course that includes the study of forces, their distribution, and impact on building structure. Topics of study include: equilibrium of rigid bodies in two and three dimensions; trusses; shear and bending moments in beams; arches and frames; stresses, strains, and deformations in axially loaded members; direct shear and bearing stresses; torsion; beam stresses and deflections; introduction to the design of structural members; and architectural applications.

Course Learning Objectives:

To increase students’ ability to visualize, problem-solve, and understand the demands as well as the behavior of building structure

To learn about the loads on a building and its structure.

Feature Focus - Structural Projects:

Students completed four projects this semester to support their learning in lecture and the homework assignments. These projects included building a model to study equilibrium (pictured to the right) , a truss which was loaded in class, a structural load path model, and a spaghetti tower which was loaded until failure.

64

Course Topics

Fundamentals: Structural mechanics, Units and Digits, Newton’s Laws

Statics of Particles: Forces and their resultants in 2D / Resolution of forces into components and their addition

Statics of Rigid Bodies in Two Dimensions: Moment of a force, Principle of transmissibility, Moment of a force / Moment of a couple, Equivalent couples, Addition of couples / Rigid bodies, Free body Diagrams, Reactions / Equilibrium of two-force and three-force bodies

Analysis of Structures: Introduction to Trusses / Trusses, analysis by method of joints / Trusses, analysis by method of sections / Cables / Beam loading and supports, shear and bending moment diagrams

Friction: Laws, coefficients, and angles

Building Loads: Dead vs Live / Dead / Live / Environmental / Loading Diagrams

Geometric properties: Center of gravity, Centroids, and Composite sections / Moment of Inertia, Parallel-axis Theorem

Concepts of Stress: Stress / Stress on an inclined plane / Deformation / Strain

Stress and Strain: Tension and Compression test / Stress/Strain Diagrams, Hooke’s Law / Ductile and Brittle Behavior / Poisson’s Ratio

Axial Loading: Saint-Venant’s Principle / Elastic Deformation / Principle of Superposition / Temperature

Torsion: Torsion formula, Circular members in torsion / Polar Moment of Inertia, Shear Stress / Torsional deformation and Angle of twist

Beams in Bending: Shear and Moment diagrams / Moment diagram in relation to the elastic curve / Beam stresses in pure bending / Beams of two materials

Beams in Shear: Shear on horizontal face of beam / Shearing stresses / Longitudinal shear and shear flow

Combined Loading: Stress cause by combined loading

Deflection of Beams: Elastic Curve Equation / Deflection Equations / Method of Superposition

Columns: Stability and Critical load / Euler formula, Radius of Gyration / Columns with various types of supports

66

Load Capacity of Trusses (Pictured Above) - students and graduate teaching assistant testing the load capacity of trusses.

Load Path Models (Pictured Below and Left)

Load Capacity of Trusses (Pictured Above) - students and graduate teaching assistant testing the load capacity of trusses.

Load Path Models (Pictured Below and Left)

Spaghetti Structures (Pictured Right): Students compete and test out group-constructed spaghetti structures. The structures are tested with loading of varying weights.

Equilibrium Projects (Pictured Page 68): Students completed equilibrium design projects along with printed boards explaining the means of equilibrium.

IASAP•BV

Illinois Architecture Study Abroad Program

70

At Barcelona-El Vallès

71

The Illinois Architecture Study Abroad Program at Barcelona-El Vallès [IASAP•BV] is a yearlong comprehensive international learning experience available to undergraduate students enrolled at the Illinois School of Architecture (ISoA) of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. It provides a unique opportunity for living and studying in an historically and architecturally vibrant overseas environment while simultaneously offering a curricular structure that is

fully equivalent –in content and academic rigor— to the courses offered on the Illinois campus.

The Program’s mission is to provide students with a multicultural and cross-national approach, enriching their personal and professional development.

It is committed to providing a holistic and dynamic architectural education that includes required courses and a wide range of curricular and extracurricular activities that focus on an integrated approach to the

72

“

Learning how to learn: that’s the main goal of the IASAP-BV program. When students are out of their zone of comfort, away from their familiar environment, they are forced to question everything they know and everything they have learnt until that moment, both from a personal and an educational point of view. Participating in that experience provides students opportunities to discover their own abilities to learn by themselves.”

Núria Sabaté, IASAP-BV Professor of Architectural Design.

IASAP•BV

discipline of architecture, continuing the students’ academic education on the same path toward graduation with a BS in Architectural Studies from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The IASAP•BV is part of an overarching institutional agreement between the Schools of Architecture of the University of Illinois at UrbanaChampaign and the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC) that provides for a significant and long-term

academic collaboration. The IASAP-BV is hosted at the Escola Tècnica Superior d’Arquitectura del Vallès (ETSAV), one of the two archi¬tecture programs of the highly ranked UPC. The ETSAV is located in Sant Cugat del Vallès, a small, beautiful and prosperous city within the Barcelona metropolitan area that has a rich history dating back to the medieval period. Home for many international educational programs, Sant Cugat is known for its high quality of life.

73

Photo by Adam Souhrada Fall 2016 at the Barcelona Pavilion

Faculty 2018-2019

The program’s staff is composed of a combination of fulltime and part-time members, and a wide range of especially invited guests who, based on their expertise, lead and deliver special activities such as thematic workshops, field-trips and other types of pedagogic modules. The IASAP-BV staffing in 2018-2019 is composed of:

Full-time members

Alejandro Lapunzina

Professional Architect degree, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina (1983); Master of Architecture, Washington University in Saint Louis (1987). He joined the Illinois School of Architecture in 1991 and is both a full-time faculty member and the Program’s Director since its creation in 2014; he had served as Director of the IASAP•BV’s predecessor program in Versailles (France) from 1994 to 1999 and from 2002 to 2013. In 2018-2019 he taught Architectural Design in the two semesters and coordinated the program’s curricular and extracurricular activities.

Marc Sanabra Loewe

Professional Architect degree (UPC-ETSAB, 2005),

Master Degree in Architectural Technology, specializing in Structural Analysis and Design (UPC-ETSAB, 2011), PhD in Architectural Structures (UPC-Barcelona TECH, 2014). He has his consulting firm and joined the program as a fulltime faculty member in 2018-2019. In 2018-2019 he taught the four Structures courses (two at junior level and two for seniors), acted as the students’ structural consultant in Architectural Design projects and delivered lectures and presentations in other courses.

Magalí Veronelli-Lapunzina

is the Program Coordinator; she holds a professional degree in Political Science and Public Administration, Universidad Iberoamericana, Mexico (1984, and a Master in Public Health, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina (1986). She joined the School’s Study Abroad Program in Versailles in 2007 and oversees the program’s administrative activities and students’ affairs. In 2018-2019 she conducted optional support activities such Mindfulness sessions, a cooking workshop and time-management presentations to support the students’ overseas experience.

Part-time members

Jaime Batlle Visiting Lecturer

Raimon Farré Moretó Invited guest lecturer

Carolina García Estévez Lecturer; professional Architect degree, UPC-ETSAB (2005),

PhD in Theory and History of Architecture UPC-ETSAB (2012); she holds a teaching position in Architectural History and Theory at the UPC-ETSAB; at the IASAP-BV she teaches Architectural History in the Fall semester.

Carles Marcos Padros Lecturer; Professional Architect degree UPC-ETSAV (2001), PhD in Architecture UPC-ETSAB (2016); he has his own architectural practice in Tarrassa and holds a teaching position in Architectural Design at the UPC-ETSAB; at the IASAP-BV he teachers Architectural Design in the Spring semester.

Núria Sabaté Giner Lecturer; Professional Architect degree, UPC-ETSAB (2006), Master in Theory and Practice of Architectural Design (predoctoral studies), UPC (2009); she has her own architectural practice in Barcelona and Paris and holds a teaching position in Architectural Design at the UPC-ETSAV; at the IASAP-BV she teachers Architectural Design in the Fall semester.

74

Specially invited teaching participants

Elena Albareda Fernández

Invited lecturer; Professional Architect degree, UPC-ETSAB (2005), PhD in Theory and History of Architecture UPCETSAB (2012); co-taught one module of Architectural History in the Spring semester.

Gerardo Caballero

Invited lecturer; Professional Architect degree, Universidad de Rosario, Argentina (1982); Master of Architecture, Washington University in St Louis (1986); principal of Gerardo Caballero Arquitectura, Rosario, Argentina; taught one module of Architectural History in the Spring semester.

Josep María García

Invited lecturer; Professional Architect degree UPC-ETSAV (2005), Master in History and Theory of Architecture UPCETSAB (2007), PhD in Architecture UPC-ETSAB (2012); taught one module of Architectural History in the Spring semester.

Burke Greenwood

Invited workshop leader; Architect (Barcelona and Chicago); offered workshop support sessions about portfolio design and application to graduate school process.

Josep María de Llobet

Invited workshop leader; Architectural Photographer

(Barcelona); offered a workshop on architectural photography in the Fall semester.

Celia Marín Vega

Invited lecturer; Professional Architect degree, UPC-ETSAB (2008), Master in Theory and History of Architecture UPC-ETSAB (2010), PhD in the History of Architecture, Universidad Pompeu Fabra (2018); co-taught workshop sessions in field-trips to architecturally significant sites.

Marta Serra Permanyer

Invited lecturer; Professional Architect degree, UPC-ETSAB (2005), PhD in Theory and History of Architecture UPCETSAB (2012); co-taught one module of Architectural History in the Spring semester.

Benjamin Bross

Assistant Professor, Illinois School of Architecture

David Emmons

Visiting Lecturer, Illinois School of Architecture

Jack Kelley

Principal McBride, Kelley and Baurer Architects, Chicago, USA, conducted –in Paris, Amsterdam and Sicily, respectively— one-week long intensive Traveling Workshops at the beginning of the Spring semester.

75

IASAP•BV Program Time line

2nd Generation: Class of 2016

1st Generation: Class of 2015

The first overseas program of the School of Architecture was in La Napoule, southern France, in 1969; the program moved to Versailles in 1970, where it operated without interruption until the 2012-2013 academic year; it moved to BarcelonaEl Vallès in the Fall of 2014.

76

77

3rd Generation: Class of 2017

4th Generation: Class of 2018

Class of 2019

1 year 8 courses 36 Students

only through intuition, and then analyzed using structures software. Once the structure is understood, the structure is described as a whole, now being able to understand its beauty in a different, enriched, manner that includes the nature of the structural behavior.

Q: How are the field trips set up and organized?

Q: How are the studio set up in Barcelona?

A: The studio has a strong European focus. We work with the context in dense urban fabrics of Barcelona as well as the building programs. For the Class of 2019, we are currently experimenting with residential project in studio, which is very different from U.S residential units. A part of the design challenges is to reflect the characteristics of European architecture. The studio uses Metric system to design and communicate so students can learn the system and work internationally.

Q: How many studio options do they have?

A: In the Fall semester all students work under the guidance of a team of teachers who work collaboratively (they coteach the entire course for all students); in the Spring semester, there are two sections for the senior studio (but both sections work with the same project assignment); the small number of junior-level students works under the guidance of another teacher.

Q: How are the structure courses taught in Barcelona?

A: Structures’ courses offered at the program are equivalent, in content and rigor, to the same courses offered on campus, both at the junior and senior levels. However, at the IASAP-BV, these courses are put in context by showing that structures are all around us in architecture. They are essential to properly design projects, merging/ blending order and beauty. But they also are all around us: in every object, in every natural being and in every human construction. To see so, the structures course starts by picking an everyday object or a natural being and working in finding out by intuition what is its structural behavior. Then, an outstanding Barcelona’s architecture work is picked, and its structural behavior is studied, first

A: The study abroad program allows students to visit buildings first hand in person. Every course has field trips associate to it. History course, for example, has half-day field trip once a week that goes along with the lectures. We also have a multiday field trip per semester. There is a short one in Fall semester and a long one in Spring semester. The itinerary changes every year according to the courses and other activities. For the Class of 2019 Spring semester field trip, we traveled throughout Andalusia, including Cordoba, Seville and Granada and visited some of the most important architectures in the history such as the Alhambra and some contemporary buildings like the Madinat Al Zahara Museum by Nieto Sobejano.

Q: Tell us about the workshops:

A: Workshops allowed us to take advantage of the studying abroad environment and offer student more educational opportunities. As for the Class of 2019, there are three types of workshops: the architecture urban sketching workshop, the architectural photography workshop, and the traveling workshop.

The architecture urban sketching workshop this year is taught by Raimon Farré from ETSAV. Students work in a very orchestrated sequence of assignments to improve their sketching techniques and analytical skills that ultimately ties into other courses.

The architectural photography workshop consists of a series of exercises lead by a professional architecture

78

photographer. Students improved their photographic skill significantly just within a short amount of time. Traveling workshop is a one week long intensive workshop lead by faculty from ISoA that takes place at a European city. It had taken in cities like Paris, Rome, Budapest, Brussels…etc. For the Class of 2019, there are three options: Utrecht, Holland, Paris, France, and Sicily, Italy. The workshop focuses on one theme throughout the week. It provides students the chance to experience interesting urban setting, landscape and buildings.

Q: How are the history courses taught in Barcelona?