The Case of ChettinadArchitecture & Beyond

For thousands of years, societies have strived to preserve their history using various methods available at the time. The Egyptians documented their history through complex, long-lasting architecture. Jewish scribes meticulously copied manuscripts, while Irish bards memorized historical events as professional poets. These examples illustrate how societies have recognized the importance of their heritage One reason generations document their history is to ensure the accurate preservation of stories They aim to ensure that future generations understand their cultural knowledge. Without recording these experiences and wisdom, much can be lost over time Documenting this information allows readers, viewers, or listeners to access historical insights that can be highly valuable in the present

Chettinadu, located in the heart of Tamil Nadu, India - 32 kilometres from the west coast of the Bay of Bengal, spans approximately 1,550 square kilometres This region boasts an irreplaceable cultural heritage, defining its unique identity through its distinctive built environment Included in UNESCO’s tentative list in 2014, Chettinadu has been classified into three clusters based on significant cultural values, forming the framework for our research. Over time, the region has undergone substantial changes, with its historical buildings reflecting the evolution of its heritage Known for its palatial mansions with unique architectural styles, preserving these old structures is crucial to maintaining the town’s character.

In this paper, we examine the historical background and heritage of the Chettinadu region, aiming to establish the values embedded in its built heritage using a selected set of variables. To achieve this, we analysed various parameters to understand how the values of the built heritage contribute to Chettinadu’s unique sociocultural history The town’s image is enriched by its social, cultural, historical, and architectural values. Our analysis supports the development of strategies to preserve and enhance the region’s built heritage By evaluating the varied heritage potential based on these values, planners and developers can create sustainable programs that modernize infrastructure while protecting Chettinadu’s inherent heritage values

I. Introduction

II. Chettinad

III. Chettinad Palace History

IV. Analysis Value Analysis

Swot

Sustainability

Stakeholder

V. Proposal

General Recommendations

Proposal One - The C Club (Chettinad Club)

Proposal Two – Chettinad Art Biennale

VI. Leveraging Digital Tool

VII. Business Plan

Market analysis

Operation and organisation plan

Economic-financial plan

Sustainability plan

Implementation plan

VIII. Implementation

Feasibility study and planning

Stakeholder engagement

Funding and resources

Restoration and infrastructure development

Program development

Marketing and promotion

Operations and management

Community involvement and capacity building

Risk management and contingency planning

IX. Benefits of the Project

Economic boost

Cultural preservation and awareness

Social impact

Environmental sustainability

Tourism spillover effect

Cost-Benefit assessment

X. Conclusion

I. Introduction

1.1 Indian saree

1.2 Location Map of Sivaganga

II. Chettinad

2.1 Painting of Chettiar merchant

2.2 Location Map of the heritage clusters

2.3 Chettinad house courtyard

2.4 Aerial view of a Chettinad town

2.5 Chettinad architecture details

2.6 A grand Chettinad hall

2.7 Tamilnadu Hindu temple Gopuram details

2.8 Chettinad Kottans

2.9 Kandaangi saree

2.10 Athangudi tile patterns

2.11 Chettinad food

2.12 Traditional snack varieties

2.13 Pongal

2.14 Jallikattu Bulls

2.15 Traditional Indian sweets

2.16 Pongal

2.17 Tamilnadu Hindu temple

2.18 Tamilnadu Hindu temple gopurams

2.19 Gold bars

2.20 Wooden logs

2.21 Chettinad saree business, Athangudi tile making

2.22 Aerial view of a Chettinad town

2.23 Chettinad architecture details

2.24 Chettinad railway station

2.25 Tamilnadu local bus

III. Chettinad Palace

3.1 Stamp of Annamalai Chettiyar

3.2 The Chettinad palace

3.3 The Chettinad palace – Grand hall

3.4 The Chettinad palace – Interior details

3.5 The Chettinad palace – Interior details

3.6 The Chettinad palace – A hallway

IV. Analysis

4.1 Tamil culture and heritage

4.2 Weaver at work, Chettinad Tinted glass Window

4.3 SWOT analysis illustration

4.4 Key aspects of sustainability

4.5 Components of sustainable development

4.6 Stakeholders of a project

4.7 A project team meeting

V. Proposal

5.1 Local people using technology

5.2 Chettinad town concept (Ai)

5.3 International outreach centre concept (Ai)

5.4 Permanent gallery concept (Ai)

5.5 Culinaire expérience centre concept (Ai)

5.6 Permanent gallery concept (Ai)

5.7 Biennale sites design concepts

5.8 Biennale event location map

5.9 Biennale individual zone maps

VI. Leveraging Digital Tool

6.1 ATHENA conceptual figure

6.2 ATHENA workflow concept (Ai)

6.3

VIII. Implementation

8.1 Local stakeholder discussion (Ai)

8.2 Project members collaboration 8.3 Stakeholder signing contracts

IX. Benefits of the Project

9.1 Tourists in the project site (Ai)

9.2 Local people and tourists gathered for an event (Ai)

X. Conclusion

10.1 Aerial view of the Chettinad palace 10.2 Aerial view of the Chettinad town concept (Ai)

VII. Business Plan

7.1 Local people discussing the project

There is a strong connection between the past and the future The decisions we make daily, combined with past events, influence what happens in the future. Many decisions today are based on knowledge of past occurrences. Heritage encompasses many inextricable factors and historical events Young adults often seek to understand their identity and knowing the details about heritage is an excellent way to embrace positive traits Viewing heritage as a valuable inheritance is essential It is unfortunate to have a rich heritage and remain unaware of it, as it is a part of who we are. Heritage is not only something to know and understand but also something to share with the future generations.

“Heritage” expresses our cultural identity, distinguishing us as a social group and fostering cohesion as part of our collective memory It includes symbolic elements that encompass both tangible and intangible assets passed down through generations. This heritage spans monuments and places of exceptional historical, aesthetic, ethnological and anthropological value Beyond objects and structures, it also embraces traditions, values, beliefs, and cultural expressions. Understanding cultural heritage is essential for grasping our identity, both individually and communally and it is reinforced through lived experiences and connections to the past.

The connections between cultural heritage and people are established through active and meaningful engagement with the shared heritage of our ancestors. Cultural heritage is not merely a passive legacy; it is a living component of our identity that endures across generations Physical environments are generally deeply connected to people’s historical identity, reflected in their unique built heritage Until the early 20th century, heritage was defined narrowly as monuments, archaeological sites and collections of movable history. However, the Venice Charter broadened the concept to encompass almost the entire built environment This shift, alongside the rise of conservation-oriented city planning, emphasized the importance of values in defining a town or region’s character. Identifying the attributes of these values and their varying levels of significance within the built heritage is crucial for historical preservation. Once these attributes are clearly outlined and their significance evaluated, their relative contributions to different aspects of a conservation program can be determined.

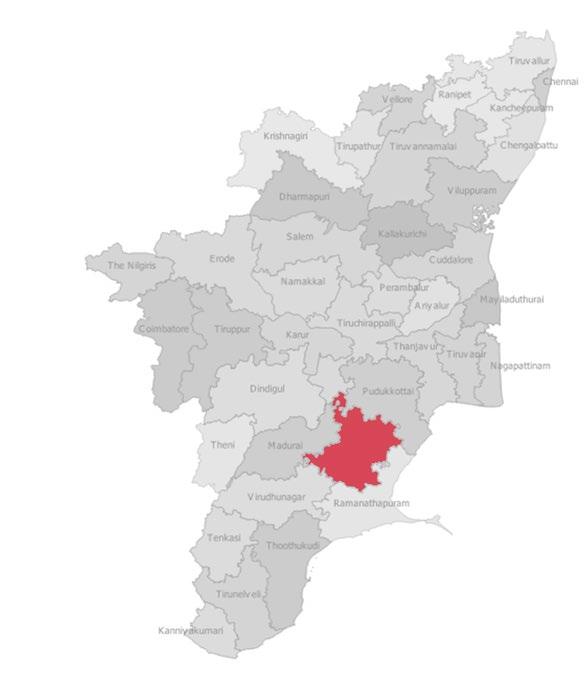

India Tamilnadu Sivaganga

1.2

Figure

Location Map of Sivaganga

Centuries ago, in the capital city of CholasPoompuhar, lived wealthy clans of merchants “The Chettiars” who traded in salt, rice, spices, valuable gems and pearls to Southeast Asian countries.

Based on the historical and archaeological records, between the 8th and 10th century, a devastating Tsunami washed away their rich abodes and the entire community migrated to a drier area which is now popularly referred to as the Chettinad region of Tamil Nadu The dwelling place for the Nattukottai Chettiars, the high-class banking and businessmen community, is located at a distance of 90kms from Madurai, in the Sivaganga district of TamilNadu, located in Southern India Nattukottai means “fort on land” – a reference owing to their palatial mansions of Chettinad. These homes were directly proportional to their wealth The grander the mansion, the better was the family fortune An amalgamation of conventional Indian architecture and a pinch of European influence derived in Chettinad house interiors. The mercantile community continued to thrive and grow From businessmen, they became money lenders to not just the villages around but to the Kings and the British East

India Company as well. District of Sivagangai Nattukottai Chettiars were basically Bankers who lent money at nominal interest rates. They are considered as the Pioneers of Modern Banking. They are the first to introduce what is called as "Pattru (debit), Varavu (credit), Selavu (expenditure), Laabam (profit), Nashtam

Figure 2.1 Painting of Chettiar merchant

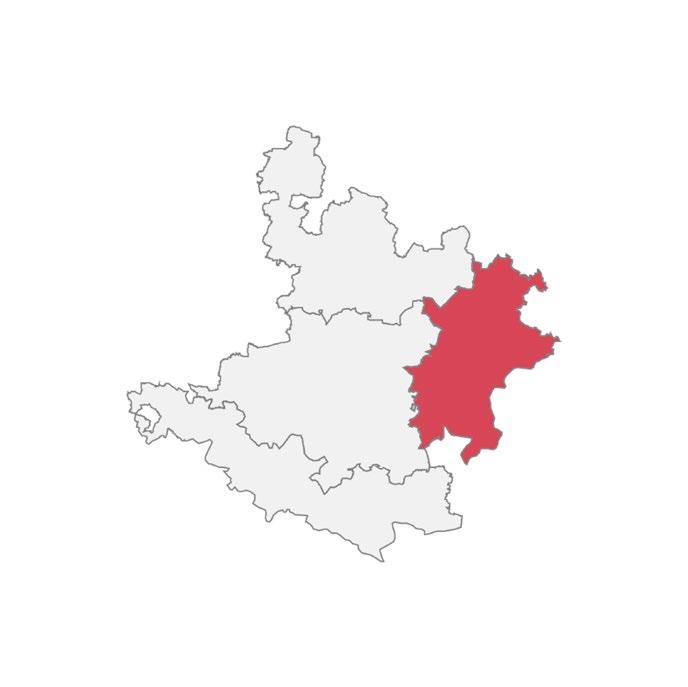

SIVAGANGA DISTRICT MAP

Karaikudi’s administrative area is highlighted in grey

ClusterIII

Rayavaram

Arimalam

Kadiapatti

ClusterI

Kanadukathan

Pallathur

Kothamangalam

Kottaiyur

palace

UNESCOrecognisedHeritageSites

Cluster I Cluster II

Cluster III

ClusterII

Athangudi

Chokalingampudur

Karaikkudi

Kandanur

Figure 2.2 Location Map of the heritage clusters

Chettinad

financial structure of the country during a period of nation-building Known for their conservative yet close-knit community, they adhered to a strict code of business ethics and were highly trusted. The Chettiars served as private bankers, money lenders, financiers, and traders, playing a dominant role in the early stages

They played a significant role in the IndoCeylon trade, controlling it by the mid-19th century and largely financing it. During the early British rule, they operated the only form of organised banking, earning the title of “Merchant Bankers of the country”. Later, they transitioned into intermediaries between British banks and the local business community Over time, they transitioned into the country’s largest money lenders, supporting local entrepreneurs.

Over time, as the business grew, a lot of them moved to cities and overseas. They built their new homes there and gradually abandoned their ancestral Chettinad mansions Today, most of them remained locked and uncared for but what remains is their dazzling magnificence (wikipedia.org, deccanchronicle.org).

Figure 2.3 Chettinad house courtyard

Figure 2.4 Aerial view of a Chettinad town

The Chettinadu region is renowned for its unique cultural assets that symbolize its distinct identity and character globally This historical town center is rich with the culture, traditions, and lifestyles of its inhabitants, showcasing designs, materials, and architectural styles handed down through generations, offering a legacy that transcends mere built heritage Chettinad has well planned towns provided with well-defined roadways, reservoirs to store and supply water to the town, a planned marketplace, temples, etc providing all the basic needs of the people.

The settlement layout of Chettinadu adheres to a grid pattern, reflecting the cultural elements of clan, caste, kinship, and joint family dynamics in the spatial arrangement of houses. The palatial homes, Erys, Ooranis, and Clan temples are unique town planning features, with the palatial mansions designed to be similar yet varying in size, details, and embellishments. Village water supply relied on rainwater harvesting, influencing the diverse designs of the mansions and settlement patterns.

These splendid Chettinadu houses, constructed between 1840 and 1935, exhibit an eclectic architectural style, particularly notable in the Art Deco homes built during the 1940s and

Figure 2.5 Chettinad architecture details

1950s. These structures have become popular attractions for heritage tours Characterized by courtyards in the center, surrounded by pillars and connected to various rooms via verandas, these mansions accommodated extended families and supported diverse activities Employing passive architectural techniques, they ensured indoor thermal comfort. The layout includes a range of spaces that are open, semi-open, and enclosed, for comfortable living across different seasons and times of the day Streets in the vicinity were narrow and shaded by overhangs, balconies, and adjacent buildings (re-thinkingthefuture.com, wikipedia org, bennykuriakose com)

The Chettinad region’s 19th-century mansions with wide courtyards and spacious rooms are decorated with marble and teak Construction materials, decorative items, and furnishings were mostly imported from East Asian countries and Europe. Many of these mansions were built using a type of limestone known as karai These mansions are known for their grand layout, with entrances on one street and exits on parallel streets. They have verandas leading to huge courtyards for festivals, connected by narrow passages Some of these mansions house over 100 rooms and feature long halls that can accommodate large gatherings.

Constructed along an east-west axis, the houses are strategically positioned to invite shadows, breezes, and coolness inside Made of baked brick and Chettinadu lime plaster, with terracotta tiles for roofing, the mansions offer a naturally cool living environment. Local Athangudi tiles adorn the floors, while exquisite wooden work decorates the doorways, often featuring lintel panels depicting Hindu mythology illustrations. Courtyards are adorned with Burma teak wood, rosewood, and satin wood Initially, columnar and tabulated patterns were prevalent, but colonial influences introduced arches on mansion facades, further embellished with geometric patterns, sculptures of Hindu deities, British benefactors, flora, and mythical creatures This fusion culminated in the distinctive architectural style known as the Chettinadu style.

Figure 2.6 A grand Chettinad hall

The tangible and intangible heritage of the Chettiars are inseparable Chettinad boasts outstanding urban and rural planning characteristics, creating a unique architectural ensemble of thousands of palatial houses. This ensemble reflects the lifestyle of the Hindu Tamil Chettiar community Through their travels, the Chettiars integrated various influences into Tamil traditions, resulting in the distinctiveness of Chettinad. Their vision of land-use planning connected different urban and landscape elements, particularly for rainwater harvesting and storage systems. The architectural features of the houses include a series of courtyards arranged along a longitudinal axis, with materials chosen to suit the semi-arid, hot climate (unesco org)

Chettinad architecture is closely linked to the lifecycle rituals of the Chettiar community The mansions were designed to accommodate various functions, rituals and family celebrations from birth to death Additionally, temple and village festivals are integral to Chettiar culture, forming a comprehensive set of rituals throughout the Tamil year. Traditional and overseas influences blend to create a unique style expressed in urban, architectural and decorative levels While the town planning characteristics remain unchanged with long series of houses, the plan, volumetric configuration and building typologies evolved

from the 1850s to the 1940s.

Pavilions, halls and courtyards were added for business purposes and as areas for receptions and weddings, adding palatial features to traditional houses Every aspect of the architecture was designed to display the owner’s wealth: from the extensive development in plan to the monumental facades, enhanced by multiple levels of balustrades and various architectural elements such as double colonnades and loggias. To construct and decorate these mansions, materials and expertise were sourced from around the world, enhancing Chettinad’s cultural glory. For example, teak wood was imported from Burma, satinwood from Ceylon, marble from Italy and Belgium, cast iron and steel from the UK and India, metal ceiling plates from Great Britain, and tiles from Bombay, Japan, Germany, France, and England. Chandeliers came from Belgium, France and Italy Skilled artisans from different regions of India were also brought in for woodcarving, frescoes and egg-plastering.

The Chettinad region also features numerous striking “Art Deco” style houses built during the 1930s and 1940s, with many villages showcasing examples of this international architectural style. The Chettiars settled in a hot, semi-arid region, strategically considering the climate in village

planning, house design and material selection shaping a unique landscape Villages are organized along north-south axes, with eastwest oriented plots creating houses around central courtyards, providing shade, light, coolness and air circulation Construction materials including thick brick walls, lime plasters, terracotta tile roofing, and marble and stone floors, respond to climatic needs. Roof slopes facilitate rainwater collection during the monsoon season, used for household purposes and to replenish wells, with excess water directed to village drainage systems feeding common ponds and tanks.

Chettiars have implemented significant earthworks to manage rainwater harvesting, enhancing traditional water management techniques on a large scale

The main courtyard serves as the central part of the house for rituals, functioning as a temple sanctuary where events are celebrated by the Chief priests of one of the 9 clan temples Each space in the house serves both daily functions and occasional ritual hosting. The cooking area holds significant importance in Chettiar houses, often hiring many cooks for celebrations This has led to the development of a sophisticated cuisine blending recipes from South India and countries where they conducted business, creating an original culinary style In addition to lifecycle traditions, temple and village festivals are integral to Chettiar culture, forming a large set of rituals throughout the Tamil year. An important local craft industry produces fine architectural and decorative elements like tiles and wood carvings, as well as ritual items such as bronze figures and gifts for weddings like sarees, basket weavings and jewels.

Figure 2.7 Tamilnadu Hindu temple Gopuram details

Chettinad is renowned for its vibrant arts and crafts scene, reflecting the cultural richness of the Nattukottai Chettiars community While the grand clan temples and opulent mansions are the main attractions, Chettinad’s local arts and crafts offer a rich tapestry of creativity and tradition The tradition of crafting “Kottans”baskets from palm leaves is deeply rooted in Chettinad culture, combining utility with craftsmanship. These intricately woven Kottans, dyed in various colours, are integral to local customs, especially during weddings, often adorned with beads and ornamental details.

The weaving community in Chettinad produces exquisite sarees, with the weavers colony being a hub of creativity and skill. Chettinad cotton sarees, also known as the Kandaangi sarees are signature pieces crafted by the Devanga Chettiyars The fabric of these sarees is known for their ability to stay cool and absorbent, ideal for hot and humid temperatures. Chettinad cotton sarees are renowned for their fine, woven look, characterized by shimmering, supple cotton fabric. Traditionally, these sarees had a shorter length ending at the calves, exposing the ankles, and were designed to be worn without blouses, providing a classic South Indian appearance The sarees are distinguished by their thick and heavy look, yet they are lightweight and comfortable. Their designs often feature dramatic checks, stripes, and

contrasting hues, creating a visually appealing effect In recent years, Chettinad sarees have gained a broader customer base by incorporating modern elements. Silk or blended cotton-silk fabrics are now used to create luxurious versions, known as Chettinad pattu sarees, which maintain traditional patterns while introducing bolder and brighter colours. These adaptations have made Chettinad sarees popular for both their traditional charm and contemporary appeal for modern-day use (artsandculture.google.com).

Figure 2.8 Chettinad Kottans

Athangudi is renowned for its handmade tiles, inspired by European designs, and highly coveted across the country for their uniqueness and craftsmanship. These tiles were named after the Athangudi village, where tile-making has become a traditional local craft carried out in the same manner even today Interestingly, these tiles are known to age beautifully and tend to get shinier with use. Athangudi tiles are handmade tiles which are used to decorate the interiors of the houses They have a distinct geometric design and come in different sizes and shapes. The standard colours used are red, mustard, green and grey.

Their manufacturing process is unique and involves the use of local soil The artisans believe that the soil of their village is just the right composition needed to make these tiles and create beautiful patterns on them, making each one unique. To start with, a metal stencil of a desired design (floral or geometric pattern) is prepared within a metal frame with handles

The artisans use hand tools to draw a free-hand design Finished tiles are dried by laying husk over them to soak excess moisture The innate oils from the husk impart a lovely sheen onto the tiles

In addition to textiles and tiles, Chettinad artisans craft a variety of kitchen utensils from clay, wood, and metal, which continue to be used today From vegetable cutters to coconut graters, these utensils showcase the region’s traditional craftsmanship and practicality.

The temples in Chettinad feature brass and bronze artifacts, intricately crafted with motifs inspired by local flora, fauna, Hindu mythology, and abstract patterns During festivals like the Sevvai Perum Thiruvizha, terracotta models of animals are made and adorned for worship, reflecting both religious devotion and artistic expression. These creations, while rooted in religious customs, also highlight the community’s deep-seated affinity for craftsmanship and creativity.

Figure 2.9 Kandaangi saree

Figure 2.10 Athangudi tile patterns

Chettiar cuisine is a gourmet’s delight, characterized by a generous use of pepper rather than chili, resulting in a spicy but not overly hot flavour The subtle spicing relies on an instinctive blend of ingredients, leading to a culinary experience that is both intriguing and delightful. This cuisine embodies a sensitivity to taste, an inherited sense of thrift, and a commitment to creating food that is both tasty and healthy. The Chettiar dining experience is renowned not only for its abundance but also for its subtle and aromatic flavours, a legacy of the Chettiar’s involvement in the centuries-old spice trade This global exchange of spices from regions like Cochin, Penang, the Banda Islands, and Arab ports in the Straits of Hormuz has deeply influenced their culinary traditions (tamilnadutourism.tn.gov.in).

Figure 2.11 Chettinad food

Chettiar cuisine is famous for its use of a variety of spices, particularly in non-vegetarian dishes. The food is hot and spicy, with fresh ground masalas. The Chettiars also make sun-dried salted vegetables called vatthals, used during off-seasons, reflecting the region’s dry environment and economic nature The meat is usually limited to fish, prawn, lobster, crab, chicken, and mutton, as Chettiars do not consume beef or pork. Most dishes are served with rice and rice-based accompaniments such as idlis, dosas, appams, idiyappams, and adais They have also adopted a type of sticky rice pudding made with purple rice, called “Kavanarisi,” from their mercantile contacts with Burma Chettinad cuisine offers a variety of vegetarian and non-vegetarian dishes Popular vegetarian items include idiyappam, paniyaram, vellai paniyaram, karuppatti paniyaram, paal paniyaram, kuzhi paniyaram, kozhakattai, masala paniyaram, adikoozh, kandharappam, seeyam, masala seeyam, kavuni arisi, and athirasam. The use of seafood is prominent, with signature dishes such as meen kuzhambu (fish curry), nandu (crab) masala, sura puttu (shark fin curry), and eral (prawn) masala

Among the most celebrated Chettinad dishes is Chettinad Chicken or Chettinad Kozhi, featuring tender chicken simmered in a blend of roasted spices and coconut

Figure 2.12 Traditional snack varieties

The Chettinad calendar is filled with various festivals throughout the year The two main notable ones are Pongal and Navaratri The Tamil harvest festival, celebrated in January, lasts for five days and is marked by communal festivities. Rice is boiled and shared in public, fostering community spirit The second day, “Mattu Pongal,” is a unique Tamil Nadu thanksgiving festival. The morning is dedicated to adorning and offering Pongal to cattle, while the afternoon features “jallikattu” a thrilling bull run where youths attempt to remove garlands from the bulls’ horns, providing an adrenaline rush for participants and spectators alike.

Pongal is the most popular and significant Harvest Festival of Tamilnadu. Celebrated with great religious fervour, Pongal is the time to give thanks to the Sun God, Mother Nature, and all the farm animals who contributed to a bountiful harvest. It’s a four-day festival that starts with Bhogi Pandigai or Bhogi Pongal People offer prayers to Lord Indra, the God of Rains on this day. The main festivity of Pongal falls on the second day and is called Thai Pongal.

Figure 2.13 Pongal

Thai Pongal is dedicated to the Sun God and a special sweet dish called ‘Pongal’ is offered to him for embracing the harvest with his warmth and energy The third day, Mattu Pongal, celebrates cows and their holiness

The Pongal Festival ends with Kaanum Pongal, also known as Kanya Pongal during which women and young girls perform a special kind of ritual called Kanu Pidi and pray for the wellbeing of their brothers The Pongal Festival usually commence on the 14th day of January every year.

Celebrating the beginning of spring and autumn, Navaratri is a significant festival worshipping the Divine Mother. The dates are set according to the lunar calendar Navaratri honours the goddesses Lakshmi, Saraswati, and Durga, manifestations of Shakti (Female Energy or Power). The festival, also known as the ‘Nine Nights festival,’ often extends to a tenth day, celebrating the culmination of nine days and nights of joyous festivities, with particular emphasis on celebrating the women of the household.

One of the grandest festivals of Tamilnadu, the Chithirai Festival, also known as Chithirai Thiruvizha showcases the enactment of the crowning of Goddess Meenakshi and the divine union of Lord Sundareswarar and Goddess Meenakshi. This two-week-long grand festival takes place at the famous Madurai Meenakshi Temple in the Tamil month of Chitrai which falls between April and May The main highlight is the car festival of Madurai Meenakshi Temple which runs through the streets of Madurai during Chithirai

An impressive display of sport and culture, Jallikattu Festival honours the spirit of hard-working Tamil farmers while showcasing the bravery and strength of the bulls they have tamed and domesticated. Jallikattu takes place

Figure 2.14 Jallikattu Bulls

in an open ground where a ferocious bull is let loose amid hordes of people who try to tame it by controlling its horn. The bulls that triumph in the festival bag the highest price in markets and are used for breeding. This extreme spinechilling spectacle is often celebrated on Mattu Pongal, the third day of the Harvest Festival of Tamilnadu, Pongal

The beautiful state of Tamilnadu comes alive with dazzling festival lights and vibrant festive spirit during Diwali, making it a spectacular sight to behold Diwali commemorates Lord Krishna’s victory over the demon Narakasura and Tamilnadu celebrates it in a simple and traditional manner.

Festivals and Ceremonies

Figure 2.15 Traditional Indian sweets

The Diwali celebration starts with people taking an oil bath in the morning before sunrise as it is the most important custom of the festival, revered as holy as a bath in the Ganges. Apart from the ritual bath, Diwali celebrations in Tamil Nadu also include decorating the entrance of homes with beautiful Kolam (Rangolis), bursting firecrackers, and eating sweets and other special Diwali delicacies

Marriage is the grandest celebration in a Chettiar family, marked by a majestic ceremony that spans a minimum of three days and includes various traditional rituals. The bride’s trousseau is renowned for its vast array of items made from gold, silver, and steel.

It is customary to gift the bride a multitude of items, from diamonds to broomsticks, in multiples of seven. Despite many Nagarathars living away from their ancestral villages, they prefer to hold their children’s weddings in their native places Historically, Chettinad marriages were even more elaborate, extending over six days and filled with numerous rituals and customs, including extensive gift-giving for the newlyweds’ wellbeing In addition to weddings, moving into a new house and celebrating the attainment of sixty years of age are also major events, celebrated with much pomp and ceremony in Chettinad

Figure 2.16 Pongal

The central theme of Chettinad culture is worship, with every Chettinad village having at least one temple, and some having as many as four or five. Each temple hosts an annual festival called ‘tiruvila,’ attended by the entire village as an act of collective worship. Originally built by early Tamil dynasties like the Cholas, these temples form the core of Chettinad’s culture. It’s said that the Nagarathars cannot do without constructing a temple wherever they reside, leading to numerous temples dotting the Chettinad region, each with its own tank, or oorani, where water lilies grow.

The Chettiars were invited to their current settlement by the reigning king of the region. Within the Nagarathar community, various clans were identified with different temples. This association determined marriage protocols within the community, as individuals from the same temple clan were considered siblings and could not marry each other. Town planning revolved around these temples, influencing culture, architecture, and business Temples play an immeasurable role in defining Chettinad’s history and culture.

Temples and Worship

Figure 2.17 Tamilnadu Hindu temple

There are nine clans in the Chettinad community, each associated with a specific temple, making nine temples particularly famous: Illaiyathangudi, Mathoor, Vairavankoil, Nemamkoil, Illupaikudi, Surakuddi, Velangudi, Iraniyur, and Pillaiyarpatti. Each temple is unique and religious activities have dominated daily life in these regions for centuries, with traditions and rituals passed down through generations.

A distinctive feature of any Chettinad house is the decorative art of “Kolam,” practiced every day at dawn on the cleansed threshold of the house This art is particularly prominent during auspicious days and lifecycle rituals such as birth and marriage, adding to the rich cultural tapestry of the Chettinad region (indiaculture gov in)

Figure 2.18 Tamilnadu Hindu temple gopurams

The Chettiars were originally relocated to a dry, dusty inland area of South India after a flood had washed away their villages The infertile land was unsuitable for farming, so they turned to trading, developing a reputation for trustworthiness due to their small, closely-knit community where intermarriage fostered strong family ties

For centuries, the Chettiars traded in salt and semi-precious stones, leading urban lives with little interest in cultivation. They sailed across seas to trade and accumulate wealth The British initially engaged the Chettiars to finance rice cultivation in Burma, and although they started as agents for British banks, they quickly became prominent money-lenders The Nagarathar community established trade contacts with countries like Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia, and to some extent, Mauritius and South Africa Most of their wealth was earned abroad and sent back home for savings. Domestically, the Chettiars engaged primarily in banking and later diversified into agriculture, industry, and other businesses

Trade and Economy

Figure 2.19 Gold bars

Figure 2.20 Wooden logs

Figure 2.21 Chettinad saree business, Athangudi tile making

UNESCO’s heritage site listing program has significantly advanced urban conservation in recent years The inclusion of Chettinadu’s historic structures in UNESCO’s tentative World Heritage Site list in 2014 has elevated this region of Tamil Nadu on the heritage tourism map Nowadays, Chettinad mansions are highly sought-after locations for film shootings and are renowned tourist attractions.

The Edaikattur Church, built in the Gothic architectural style modelled after the Reims Cathedral in France, features stunning statues imported from France over 110 years ago The holy Kaleeswarar temple in Kalaiyarkoil, Sivaganga District, boasts a large and impressive structure surrounded by a robust stone wall and two Rajagopurams The Kannadasan Memorial in Karaikudi honours the renowned lyricist who elevated Tamil film songs to great heights Deivam Wonderland, located near Pillayarpatti, and Kandadevi Temple, near Devakottai, offer further cultural and spiritual experiences. Kundrakudi Temple, 10 kilometres from Karaikudi, dates back to around 1000 AD and was renovated by the Marudhu Pandiyars Kings of Sivaganga (tamilnadutourism tn gov in)

Marudupandiyar Memorial is situated in the Swedish Mission Hospital Campus, Tiruppattur Pillaiyarpatti Temple, a rock-cut temple, showcases the images of Karpaga Vinayaka and a Siva Linga carved out of stone. Ilayankudi Mara Nayanar, one of the 63 Saivite saints, was a farmer and devoted servant of Lord Siva Thirukostiyur Temple, among the 108 Vaishnava temples, is visited by Alwar Ramanujar and dedicated to God Sri Vishnu, also known as Swami Narayana Perumal

Figure 2.22 Aerial view of a Chettinad town

Figure 2.23 Chettinad architecture details

Trichy (TRZ) and Madurai (IXM) airports are 80 km and 110 km away, respectively, taking 2 hours and 1½ hours to reach Saratha Vilas The nearest major airport to Chettinad is Madurai International Airport (IXM), approximately 90 kilometres away. From the airport, one can hire a taxi or use public transportation to reach Chettinad

The Chettinad region is also well-connected by rail, with the nearest railway station being Chettinad Railway Station (CDMR). Trains from major cities in Tamil Nadu and neighbouring states provide convenient access. From the station, local transportation options like autorickshaws or taxis are readily available. Karaikudi Junction, the nearest major train station, is 16 km from Chettinad and connected to Chennai by two daily direct overnight trains

Chettinad has good road connectivity, and one can reach the region by road from various cities in Tamil Nadu Chettinad is well connected to Trichy, Thanjavur, and Madurai by road, with a travel time of approximately 2 hours. It takes about 7½ hours to drive directly from Chennai International Airport and 5 hours from Pondicherry Karaikudi, the largest town in Chettinad, serves as a major transportation hub. State-run buses, private taxis, and rental cars are available for a comfortable journey

Karaikudi is well-connected to major economic hubs in Tamil Nadu, facilitating smooth travel for business and economic activities. Chennai, the state capital and a major economic hub is accessible from Karaikudi by road and rail Direct buses and trains run regularly between the two cities, making it convenient for business travellers. The drive from Chennai to Karaikudi takes approximately 7½ hours Madurai, another significant economic center is around 90 kilometres from Karaikudi. The city is easily reachable by road within 2 hours. Frequent buses and taxis connect the two cities, ensuring easy access for economic activities Trichy (Tiruchirappalli), located about 100 kilometres from Karaikudi is an important commercial and industrial hub.

The city is connected by well-maintained roads and railways, with travel time by road being approximately 2 hours Regular buses, trains, and taxis provide efficient transportation between Trichy and Karaikudi. Coimbatore, known for its textile and manufacturing industries is accessible from Karaikudi by train and road Though farther away, the rail network offers direct train services, while road travel can take around 6-7 hours. These connections ensure Karaikudi remains integrated with Tamil Nadu’s major economic hubs, supporting both business and economic growth in the region

Karaikudi is well-connected to major tourist attractions in Tamil Nadu, offering convenient access for travellers Madurai’s famous Meenakshi Amman Temple is approximately 90 kilometres from Karaikudi, accessible by road within 2 hours, with frequent buses and taxis providing transport Trichy’s Rockfort Temple and Srirangam Temple are around 100 kilometres from Karaikudi and the travel time by road is approximately 2 hours, with regular bus and taxi services available Thanjavur, home to the UNESCO World Heritage site, Brihadeeswarar Temple is about 150 kilometres from Karaikudi and is accessible by road, with a travel time of around 3 hours. Buses and taxis frequently connect the two locations Rameswaram, a major pilgrimage site with the Ramanathaswamy Temple is approximately 140 kilometres from Karaikudi. The drive takes about 3 hours, with buses and taxis providing regular service Pudukkottai, known for its historical sites like the Sittanavasal Cave is about 45 kilometres from Karaikudi, easily reachable by road within an hour.

The region itself offers access to the architectural heritage and cultural richness of Chettinadu, with its palatial houses, unique cuisine, and vibrant festivals These connections make Chettinadu an excellent base for exploring some of Tamil Nadu’s most renowned attractions

Figure 2.24 Chettinad railway station

Figure 2.25 Tamilnadu local bus

Amidst the vast expanse of 11,000 abandoned mansions that now stand dilapidated like forgotten treasures, stands the majestic grandeur “The Chettinad Palace”. The Chettinad Palace is located 15 kilometres away from Karaikudi town. The Chettinad Palace is located 14 kilometres away from Karaikudi town Sri S RM M Annamalai Chettiyar was an industrialist, banker, educationist and philanthropist. Born in a wealthy Nagarathar family, he joined the family business early and expanded their banking operations to SouthEast Asia. He was honoured the hereditary title of “Raja of Chettinad” in 1929. He established a stable business in Burma (Myanmar) and expanded into financing activities In collaboration with the Chettiyars of the neighbouring villages, they successfully connected the financial needs of developing countries with those having excess liquidity through arbitraging, despite the absence of modern communication facilities. Their business was built on trust and acumen. He is also the founder of Annamalai university and one of the founders of Indian Bank

In 1905, Sri S.RM.M. Annamalai Chettiar began constructing a majestic house on the huge plot, employing 150 workers, including masons, painters, blacksmiths, artists, and carpenters, primarily from the Tirunelveli and Nagercoil regions (wikipedia.org).

With so many beautiful ornamental details it took seven years to complete the construction of the palace. The construction was completed in 1912, funded by hard-earned money from overseas ventures. Materials were sourced globally and transported innovatively Despite the lack of electricity, cement, and modern

tools, the passionate workforce achieved 100% perfection

The house is also called as “Kanadukathan Palace”. This palace is the composite of art, architecture and tradition. As an example, it exposes the cultural facets of Chettinadu people The wishes of Chettiars are found elsewhere throughout the structure. Ornamental lights, teak wood materials, glasses, marbles, carpets and crystals were imported from overseas for the construction of the building. In spite of that it has different types of arts and styles in unique way.

Figure 3.1 Stamp of Annamalai Chettiyar

Figure 3.2 The Chettinad palace

The foundation of the house is constructed with an arch foundation using bricks and stones The walls are coated with a mixture of lime mortar, egg white, jaggery, and kadukkai (black myrobalan). The ceiling is made with an interlocking system of tiles, wood, and brick, supported by stone pillars, wooden logs, and steel beams All the grill work was done with riveting, as welding was not practiced at the time. Many architects researched about the architectural pattern of this palace The palace has ornamental works throughout the building and wood works carried out from the wood which was imported, many of them from East Asian countries and Europe.

Evidence of the grandeur of Chettinad Palace is apparent right from the porch. The first step reveals an intricately designed floor adorned with colourful tiles. Ornate pillars with intricate carvings and heavy doors follow, but the colourful glass windows are particularly striking The intricately designed roof also captivates, with bamboo curtains on the front porch (veranda) providing protection from the summer heat Beyond the front porch lies a second veranda, characteristic of all Chettinad homes. Unlike typical Chettinad houses, this porch exhibits a high degree of thoughtfulness in its design The walls feature both glass and stonework, while the roof maintains intricate detailing.

Figure 3.3 The Chettinad palace – Grand hall

At one end of the second porch, stairs lead to the living quarters upstairs, which are not accessible to tourists On the ground floor, opposite the stairs, lies a large, basic kitchen A main attraction of Chettinad Palace is the central courtyard, accessible from the second veranda Symmetrical pillars surround the courtyard, with doors and windows to many rooms opening into this area. Although these rooms are not open to the public, they are believed to house antique items collected by the Chettiar family over years of trading with other countries

Figure 3.4 The Chettinad palace – Interior details

While access to the rooms on the first floor is also restricted, the courtyards provide a clear sense of the palace’s grandeur Evidence of the grandeur of Chettinad Palace is apparent right from the porch. The first step reveals an intricately designed floor adorned with colourful tiles Ornate pillars with intricate carvings and heavy doors follow, but the colourful glass windows are particularly striking. The intricately designed roof also captivates, with bamboo curtains on the front porch (veranda) providing protection from the summer heat.

Beyond the front porch lies a second veranda, characteristic of all Chettinad homes. Unlike typical Chettinad houses, this porch exhibits a high degree of thoughtfulness in its design The walls feature both glass and stonework, while the roof maintains intricate detailing. At one end of the second porch, stairs lead to the living quarters upstairs, which are not accessible to tourists On the ground floor, opposite the stairs, lies a large, basic kitchen.

A main attraction of Chettinad Palace is the central courtyard, accessible from the second veranda Symmetrical pillars surround the courtyard, with doors and windows to many rooms opening into this area. Although these rooms are not open to the public, they are believed to house antique items collected by the Chettiar family over years of trading with other countries.

Materials for the palace were sourced globally, evident in every detail. Colourful glasses from Belgium, tiles from Italy, and teak wood from Myanmar were used, with the famous Athangudi tiles enhancing the overall aesthetic The design reflects a significant Indo-European architectural influence. While access to the rooms on the first floor is also restricted, the courtyards provide a clear sense of the palace’s grandeur The huge open courtyards ensure daylight and cross-ventilation. A palace with more than 500 ornate stained-glass windows and 64 large rooms, more than 100 rooms in total, tiles from Italy, coloured glasses from Belgium, huge wooden doors and windows with intricate carvings, and colourful works of art. The main entrance, made of Burmese teak wood with intricate carvings that amaze everyone, is one of the main attractions here The magnificent works of art here are the colours and the carvings. Belgian glass windows create a kaleidoscope of colours

Figure 3.5 The Chettinad palace – Interior details

Unfortunately, most of the Chettinad Heritage palaces are in deplorable conditions. Luckily that’s not the case with the Chettinad Palace It is said that though the family members of the original owners of the palace no longer live here, the extended family continues to visit it from time to time, especially during Diwali and other important festivals

Currently, the palace is owned by Annamalai Chettiyar’s descendants, specifically within the family, which includes prominent figures like A.C. Muthiah, a well-known industrialist and the son of M.A. Chidambaram. A.C. Muthiah has been involved in various business ventures and is a significant figure in the management of the family's assets, including the palace. The family members has abandoned their home and moved to bigger cities However, the government has banned demolish of such mansions. The property is currently taken care by the managers and is said to be worth crores of rupees. The mansion requires regular maintenance and colloquially it is said to be equivalent to keeping an elephant as a pet (businessinsider.com).

The paintings done using local vegetable dyes are still very bright and colourful. The mansion remains unused almost all the time Many tourists visit Chettinad to see the palace, but it remains closed for tourists. However, people still visit the palace to see the grand, magnificent view from outside Movie productions were also done outside the palace

However, in recent decades, the region’s historical monuments and sacred precincts have suffered from inadequate town planning and the indifference of both government and locals towards heritage preservation. Unregulated urbanization and tourism are threatening these unprotected and unlisted heritage structures, leading to their demolition. Rapid and excessive development is irreversibly altering the heritage characteristics of these towns If this degradation continues, India risks losing one of its most treasured cultural identities. Therefore, it is crucial to preserve and restore these priceless buildings and monuments

Current situation

Figure 3.6 The Chettinad palace – A hallway

The data presented in this report and accompanying presentation is derived from a comprehensive review of multiple authoritative sources to ensure accuracy and depth The UNESCO tentative list provides critical insights into the global significance and conservation status of the Chettinadu region. Tamil Nadu Tourism and the Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology offer detailed descriptions of the region's heritage sites, cultural practices, and historical context. Additionally, the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, provides overarching perspectives on the cultural significance and preservation efforts for world heritage sites across India. Specific local information

https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5920/

https://www.biennialfoundation.org/biennials/k ochi-muziris-biennale-india/

https://www.tamilnadutourism.tn.gov.in/

https://www.tnarch.gov.in/

https://www.indiaculture.gov.in/world-heritage

https://sivaganga.nic.in/tourism/

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nagarathar

https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/

and tourism highlights are sourced from the Sivaganga district's official site, while Wikipedia’s Karaikudi page offers an overview of the area's cultural and historical relevance. Chettinad Palace's official site and Benny Kuriakose’s professional blog offer specialized architectural insights, and Google Arts & Culture provides access to a rich repository of visual and contextual data Lastly, Business Insider contributes a contemporary perspective on heritage tourism and its economic implications. Together, these references form a robust foundation for the analysis and recommendations presented, ensuring a well-rounded and thorough understanding of Chettinadu's unique built heritage and cultural values.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karaikudi

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanadukathan_ Palace https://www.thebangala.com/architecture/

https://www.businessinsider.com/

https://www.bennykuriakose.com/

https://artsandculture.google.com/

https://www.deccanchronicle.com/

https://www.thehindu.com/

Figure 10.2 Aerial view of Chettinad town concept (Ai)

Arun Madhavan Jayasankar (10962363) I Gayathri Krishnamoorthi (10962369)