15 minute read

HIDDEN HISTORIES

The Royal College of Physicians of Ireland’s Heritage Centre is a treasure trove of fascinating stories of medicine, murder and curious mementos.

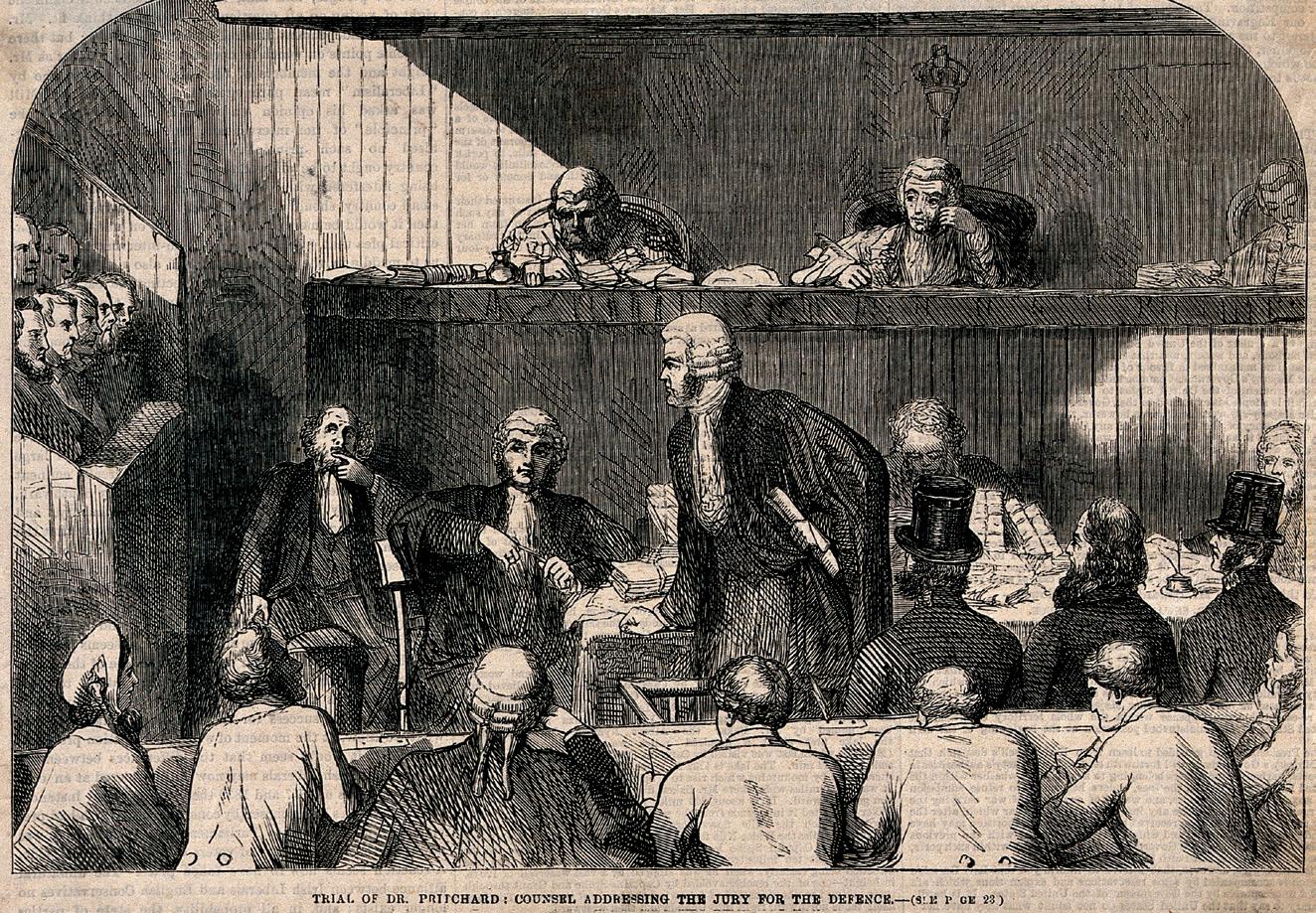

In Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes story, The Adventure of the Speckled Band, the famous detective tells Dr Watson: “When a doctor does go wrong, he is the fi rst of criminals. He has nerve and he has knowledge. Palmer and Pritchard were among the heads of their profession.”

The Pritchard referred to was notorious enough at the time that the author could assume his audience knew who he was talking about, and what he had done to be considered “the fi rst of criminals”.

The facts behind his chilling story may have been forgotten over time but they were recently unearthed among the vast amount of records and artefacts of interest kept in the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland’s (RCPI) Heritage Centre Collections by Keeper of Collections Harriet Wheelock.

His story of murder and execution is just one of many in the Heritage Centre, which is a hidden gem for anyone interested in medical history and its sometimes dark or odd connections to history. Located at the RCPI building at 6 Kildare Street, it holds more than 50,000 items relating to the history of medicine and medical education in Ireland, including books, archives, photos, paintings and objects.

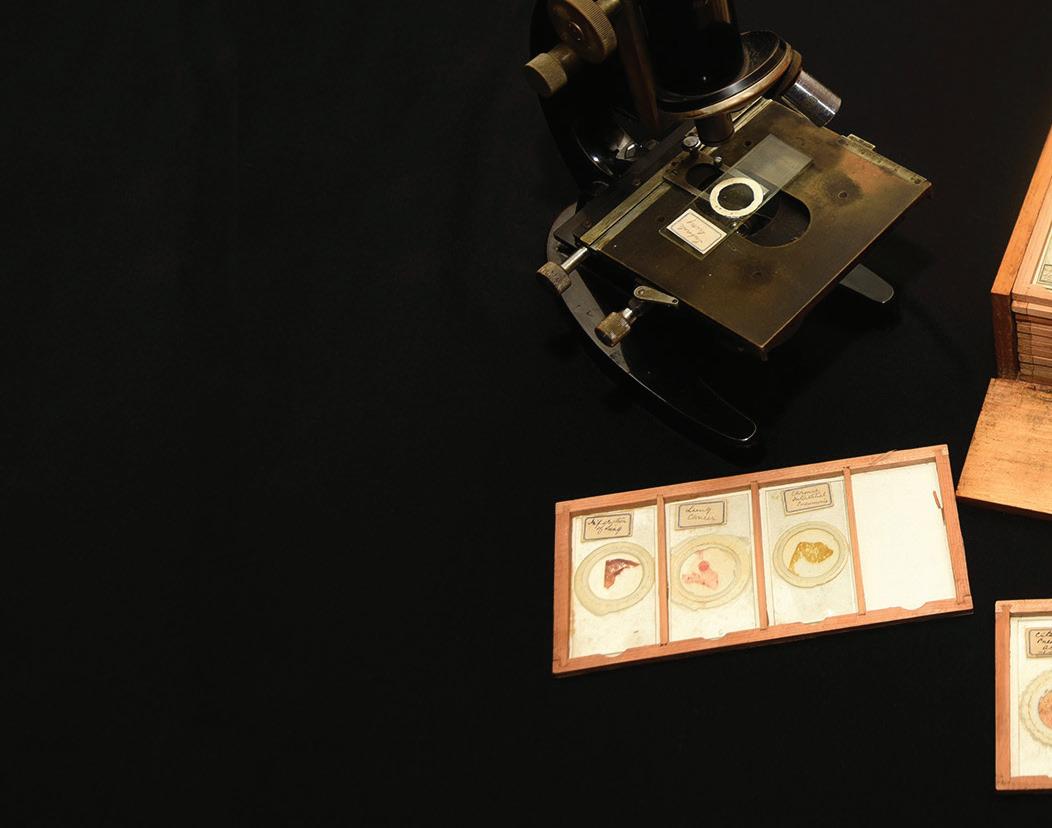

Old medical equipment on display at the Heritage Centre.

Unfortunately impacted by the pandemic, tours and research opportunities are currently closed to the public, but the Heritage Centre website features online exhibitions and recordings of talks on various topics, and there are plans in place to expand the display space within the building to accommodate bigger exhibitions in the future. For now, these records await curious eyes, and the inquisitiveness of historians and researchers is what led Harriet to the story of this Dr Pritchard.

MURDER

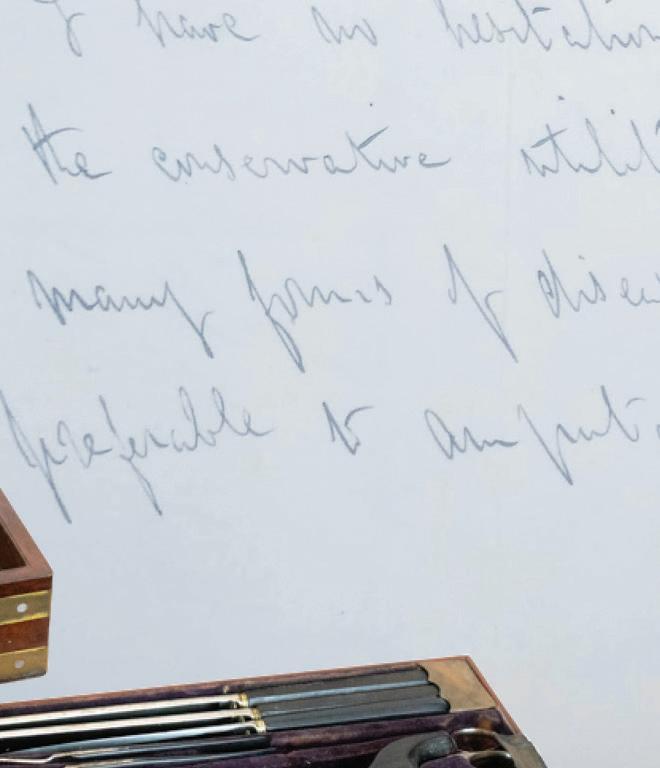

“I came across this story completely by chance,” she tells me. “We have a collection of about 200 letters that were written to an Irish surgeon called Richard Butcher who was working in the 1840s and 1850s and was famous for a particular knee operation. He wrote to doctors across Ireland and Britain, surveying them on whether they had carried out this operation, the results, and how they had carried it out, which he was particularly interested in because he had devised a tool called Butcher’s Saw.

“The letters were categorised as letters to Dr Butcher but had little other information, but a couple of years ago I started working through them to see if I could fi nd more information, and one of the things I did was identify who the doctors were, which is quite easy to do because the medical directories published in the 1850s list every doctor in the British Isles.

“I came across a series of letters from a Dr Edward Pritchard, and looked him up in the directory to fi nd out who he was, and because there were quite a few letters, I decided to research him online. It turns out he was more interesting than I was expecting because he was a notorious murderer whose case shocked society in the mid-1800s.”

Hampshire-born Pritchard trained in medicine in the Royal Navy before working in a practice in Yorkshire, at which time he wrote frequently to Dr Butcher and was quite complimentary about him. He moved to Glasgow in 1859, and four years later, things took a turn.

After a fi re at his house, the body of a servant girl named Elizabeth McGrain was found. The fi re had started in her bedroom but there were no signs of any attempt by her to escape, so an investigation thought it possible that she was probably either dead or unconscious when the fi re broke out.

“There wasn’t enough evidence for a prosecution,” Harriet tells me, “but two years later, Pritchard’s wife Mary Jane Taylor, the daughter of a wealthy silk merchant, and his motherin-law, died within three weeks of each other at the family home. Both had been treated by Pritchard, with the help of another doctor named Dr Paterson, who grew suspicious of their illnesses and refused to sign the death certifi cates, which Pritchard presumably signed himself.

“An anonymous letter was sent to authorities, which led to the bodies of the two women being examined, and they were found to contain an extremely nasty poison called antimony. Pritchard was convicted of both murders and was executed in 1865, becoming the last person to be publicly hanged in Glasgow.”

Arthur Conan Doyle, who had studied medicine and based his famous creation on his medical school professor Dr Joseph Bell, would have been familiar with the case, hence the reference in his story.

“The letters themselves are clinical,” Harriet tells me, “but because of who he was, they become much more interesting. You wonder, if several years after Butcher received these letters from Pritchard, if he remembered their correspondence,

One of the letters from murderer Dr Pritchard to Dr Butcher.

The trial of Dr Pritchard shocked society (copyright The Wellcome Collection).

and how he felt to have written back and forth to a person who ended up murdering his wife and mother-in-law.”

TRIALS

“Kirwan obviously knew a lot of people in the medical profession and there were quite a lot of pamphlets published about the case, including not just doctors giving their views in court, but also character references, so he had a lot of infl uential people on his side, which may have helped,” Harriet says. “His illustrations tend to be quite popular to visitors because they are quite graphic,” she adds, “but there is certainly an interest in the gruesome side of his story, and we try to strike a balance between the sensational and the valid reasons for displaying such items in a medical history collection. He certainly is an interesting fi gure. “I’m sure there are more stories like those of Pritchard and Kirwan in The fact that it was revealed at his our collections, it is just a matter of court case that he had a mistress and uncovering them. For instance, with eight children living in Sandymount Pritchard, if I hadn’t gone through gave the prosecution motive, but those letters, we never would have despite being convicted of the found out about his notorious life. murder, he wasn’t sentenced to Certainly in the library there are The Collections also have a death and was instead transported. many accounts of doctors giving connection to another notorious Kirwan had a considerable defence evidence in court of poisonings, murder case that came to light when led by barrister, MP and Home Rule and for researchers there is a a researcher approached Harriet advocate Isaac Butt, and was not huge amount of records here that about a Dublin-born artist called short of character references, which means they could get to uncover William Burke Kirwan. probably saved him from new information.”

“Kirwan was an artist specialising the gallows. in medical illustrations in the 19th in medical illustrations in the 19th century, which was common before century, which was common before photography was available. He would photography was available. He would have been invited into hospitals, sat have been invited into hospitals, sat in on operations, and drawn these in on operations, and drawn these as well as illustrations of removed as well as illustrations of removed organs and body parts,” she tells me. organs and body parts,” she tells me.

“We have about 80 such illustrations in the collection, some by Kirwan, and when the researcher came to ask if we had researcher came to ask if we had any of his works, I was introduced to any of his works, I was introduced to the story.”

As the story goes, Kirwan and his As the story goes, Kirwan and his wife Sarah went to Ireland’s Eye on wife Sarah went to Ireland’s Eye on a day trip. She went swimming, but a day trip. She went swimming, but supposedly drowned. “It wasn’t clear supposedly drowned. “It wasn’t clear what happened, whether it was an what happened, whether it was an accident or foul play,” Harriet says, accident or foul play,” Harriet says, “but there were signs of manual “but there were signs of manual asphyxiation, so Kirwan was tried for asphyxiation, so Kirwan was tried for the murder and convicted.”

OBJECTS OF INTEREST

It’s not just in the archives that you can fi nd interesting stories, but in the can fi nd interesting stories, but in the many objects in the collections. As many objects in the collections. As well as antique medical equipment well as antique medical equipment and curios, there are some truly and curios, there are some truly unique pieces of history. unique pieces of history.

“The two most famous things we “The two most famous things we have are the diaries of Kathleen have are the diaries of Kathleen Lynn, who was Chief Medical Offi cer Lynn, who was Chief Medical Offi cer for the Irish resistance army in 1916, for the Irish resistance army in 1916, and Napoleon’s toothbrush,” Harriet and Napoleon’s toothbrush,” Harriet tells me. tells me.

Kathleen Lynn’s diary starts on Easter Monday 1916, in which she very casually starts off with ‘Easter Monday, revolution’ and goes on to talk about her role and experiences throughout the Rising. She kept this while she was in prison too, so it gives a fascinating insight into the events of those days and the aftermath.”

NAPOLEON’S TOOTHBRUSH

She adds: “I have a love/hate relationship with the toothbrush because everybody always asks about it,” but the story goes that when Napoleon was captured after Waterloo in 1815, he was taken to St Helena by the British Navy. The doctor on board was Blackrock-born Barry O’Meara, and because he spoke French he could talk to the fallen Emperor and it turns out they got on very well. Napoleon asked for O’Meara to be his personal doctor while he was in captivity, and O’Meara agreed on the condition that he would not be asked to spy on the Frenchman for the British.

“Napoleon gave O’Meara several gifts during this time, but because he was in captivity, he didn’t really have much,” Harriet says, “but he did give him snuff boxes and his toothbrush, which we have in our collection, and also a lancet O’Meara used to bleed Napoleon. The items we have from him passed through several Irish surgeons and in the 1930s were given to the College.

“O’Meara was quite outspoken “O’Meara was quite outspoken about the conditions Napoleon was about the conditions Napoleon was kept in and subtly suggested that this kept in and subtly suggested that this

Napoleon’s toothbrush. Dr Kirkpatrick, whose index details 12,000 registered doctors from the 1850s onwards.

was making him ill and was intentional, and wrote letters to British papers about it, which didn’t go down well. He was dismissed from the Navy and they tried to get him to stop practising medicine, but he moved back to London and set up a dental practice. He displayed Napoleon’s wisdom tooth that he had removed in his shop window, alongside a letter from Napoleon verifying it was his and recommending him as a dentist. So that brought in a lot of business.

“After Napoleon died, O’Meara also published an account of the time they had spent together – he had told O’Meara to keep a diary and told O’Meara to keep a diary and when the Frenchman died he could when the Frenchman died he could publish it and make a fortune. It was publish it and make a fortune. It was an overnight bestseller and O’Meara an overnight bestseller and O’Meara ended up very wealthy. ended up very wealthy.

Harriet Wheelock, Keeper of Collections at the RCPI’s Heritage Centre.

“This does tend to come up in quizzes about lesser-known Dublin: Where is Napoleon’s toothbrush? So now you know.”

ARCHIVES

The majority of the collections are from the College’s own records and archives, but since the 1860s many more items and records have been donated, so it continues to grow.

“Large portraits were donated because people didn’t have enough room for them at home, for example,” Harriet tells me, “and as medical equipment changed, we started to get the more antique equipment donated, and we do still get donations if a doctor passes away. We also get archives from working hospitals so that we can provide access to their historical items, which most hospitals are not able to do themselves.

“We have been very lucky to get some very interesting items donated, and we tend not to buy anything because it belittles the donations we have been generously donated.”

I ask Harriet if she has a particular favourite among the many objects, and she tells me about Dr Kirkpatrick.

“Dr Kirkpatrick was registrar of the College between 1910 and 1954, and the majority of the items we have are down to him because either he collected them and gave them to the College, or because he encouraged people to donate them. He collected a huge amount of information on Irish-born doctors, so we have 12,000 biographical fi les which we call the Kirkpatrick Index. He left his archive to the College, and as well as all of his medical notes and publications, he also left a small book detailing his family history research. Within that book, I discovered that we are actually distantly related. The book is my favourite item, because I appreciate the work he did for the College – I wouldn’t have this job without his contribution – but also was delighted to fi nd out we had a personal connection.”

TRACING FAMILY

The Heritage Centre can also help anybody interested in researching their own family’s links to the medical profession in Ireland, with a number of records to help trace doctors.

“Medical registration was introduced in 1858 so from that year onwards every doctor has to register every year, and any doctor who registered after that year is easy to fi nd,” Harriet says. “They are in the register with their name, address and where they worked, so you can get quite a lot of information from that. We also have the Kirkpatrick Index, so if the person you are looking for is in there, that’s great, because a lot of the work has already been done for you. On top of that we also have quite a lot of published works such as histories of hospitals, collections of biographies of doctors, so any number of source materials to help you fi nd out about the doctors in your family history.”

In normal times, you could arrange an appointment to visit the Centre and Harriet would show you what records they have and how to go about doing the research, and post-pandemic that service will return, but you can also commission the Centre to do the research for you for a small fee. The Heritage Centre has also signed a deal with ancestry.com to digitise a lot of their records, which will be worked on after the pandemic ends too.

This tracing service has brought numerous successes, and even helped to connect two separate researchers who turned out to be related. “When we are commissioned to do research, I always write up and keep a copy of the report,” Harriet tells me, “and on two occasions we had commissions for the same person from different individuals. Both were distant relatives researching the family history from different sides, so it was nice to be able to match them up.”

This research has also resulted in the discovery of more dark tales involving doctors who met untimely ends.

IRA INVOLVEMENT

“One of the more interesting ones we had was when I was asked to do research on an Irish doctor called Charles Pentland,” Harriet says. “He died in London in the 1920s. We had some information on him in the Kirkpatrick Index, with some newspaper cuttings about his death which detailed that he was killed in a traffi c accident right outside his London home. A lorry drove up onto the pavement and knocked him down.

“From reading the articles and from other documents we had, it rapidly became apparent that Dr Pentland may have been targeted by the IRA. He had been in the British Army in WW1 and then worked in Leitrim as a doctor. In 1919 or 1920, a farmer came to tell him that he had seen IRA members training nearby, and he felt duty-bound to inform the police. The farmer was killed soon after, and Pentland left for London before he met the same likely fate.

“I looked into fi rst-hand accounts of military history and there are several mentions of Dr Pentland by IRA members, one of which said that they knew Pentland was in London and that ‘it was just a matter of time’.”

From the curious to the macabre, there are countless stories to be unravelled at the RCPI’s Heritage Centre, and anyone who wants to delve into their family’s connections to the medical profession, discover more about medicine in Ireland over the centuries, or just learn about the many strange and fascinating stories behind the archives and objects held there, can look forward to the time when this pandemic ends and we can step into history once more.