2 ATHLETICS COACH -JANUARY 2018

T able of C on T en T s Click on the name of the article to jump directly to that page

3

4 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

Editorial

Welcome all to the first Athletics Coach magazine for 2018, and what a busy and exciting year we have ahead. I hope you have managed to get a bit of rest and relaxation over the holiday season and are ready for another big year.

From a High-Performance competition perspective, the Commonwealth Games on the Gold Coast during April will be the pinnacle for the year and we wish the team and personal coaches all the best of luck for the Games. What we don’t do enough though is pay credit to those coaches who contributed to the development of those athletes as children, youth, and developing adult athletes.

The proverb goes “it takes a village to raise a child”. Equally, there are many contributors to an elite athlete’s podium performance and that includes the multitude of coaches they have worked with through their development. To those coaches that were there to build those fundamental movement skills, gave support, made it fun, focussed on the personal bests, weathered the struggles and celebrated the success – thank you. Coaches are a critical determinant as to whether a participant stays in the sport or even stays active. So, many of you

will be able to look at the eight days of competition and tell stories to family and friends of the role you played in the development of athletes out there representing our country - enjoy it.

Athletics Australia Board Member, Chris Wardlaw, is keen to remind us that Athletics is a Coach driven sport, and he is right. The focus for us in 2018 is to continue to build services and learning opportunities that meet your needs, regardless of where you are motivated to coach. We will be working to build out the opportunities for personal and professional development with an emphasis on ensuring that where possible, these are not geographically restrictive. Be prepared for new courses and modules to support coaches working with recreational running groups, masterclasses in Kids’ Athletics, developing the soft skills of coaching and getting some insights from our Track and Field and Out of Stadia experts.

Enjoy this edition of the magazine, thank you for your continued commitment to keeping Australians moving and best wishes for a prosperous 2018.

James Selby General Manager - Program Development

5

March 14 to March 18

Sydney Olympic Park Athletics Centre

Athletics

Athletics

Athletics

Athletics

This information is intended to be a guide only. Please check the website of your Member Association for more information.

2018 AUSTRALIAN JUNIOR ATHLETICS CHAMPIONSHIPS

Draft Timetable Entry Standards

Entries are taken directly by the

Association. Member Association Nominations Close Registration and More Information Athletics ACT 10:00pm - January 28 Click here Athletics NSW 9:00am - February 12 Click here Athletics NT Contact Athletics NT Queensland Athletics 9:00am - February 28 Click here

NOMINATIONS

athlete's Member

SA 11:59pm - February 18 Click here

Tasmania 10:00pm - March 8 Opening Soon

Victoria 11:59pm - March 6 Click here

WA 9:00pm - February 18 Click here

ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018 6

This information is intended to be a guide only. Please check the website of your Member Association for more information.

2018 AUSTRALIAN OPEN ATHLETICS CHAMPIONSHIPS

Stadium,

Draft Timetable Entry Standards NOMINATIONS Entries are taken directly by the athlete's Member Association. Member Association Nominations Close Registration and More Information Athletics ACT 10:00pm - January 28 Click here Athletics NSW 9:00pm - January 28 Click here Athletics NT Contact Athletics NT Queensland Athletics 11:59pm - January 28 Click here Athletics SA 5:00 pm - January 28 Click here Athletics Tasmania 5:00pm - January 28 Click here Athletics Victoria 5:00pm - January 25 Click here

WA 5:00pm - January 26 Click here

February 15 to February 18 Cararra

Gold Coast

Athletics

7

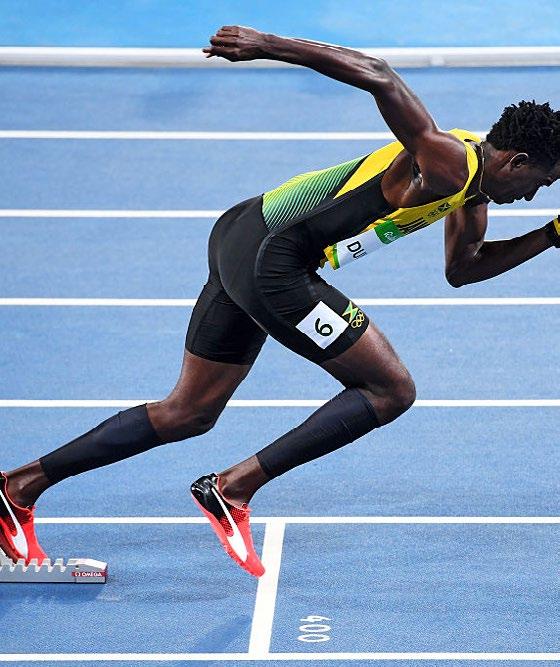

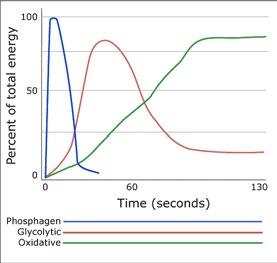

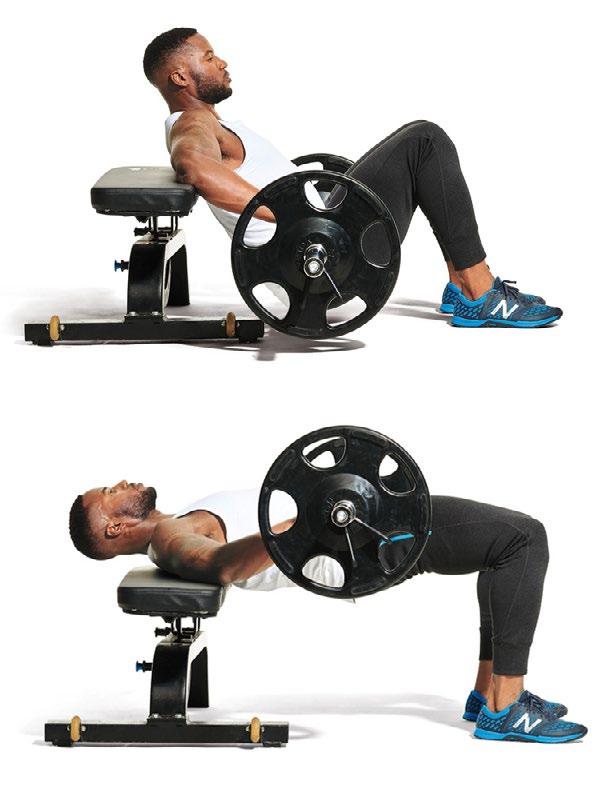

Hip Thrusts for Improving Sprinting Performance

The correlation between lower-body strength and sprinting performance has been well documented (Seitz et al., 2014; Smirniotou, Katsikas & Paradisis, 2008) and has resulted in coaches incorporating extensive strength and conditioning programs as part of a sprinter's training regimen. Traditional programs have focussed on exercises such as squats, deadlifts and/or leg curls, which have been supported by some evidence for improving sprinting performance and improving running economy (McBride, Nimphius & Erickson, 2005; McBride, TriplettMcBride, Dvie & Newton, 2002; Yetter & Moir, 2008).

8

Improving Performance

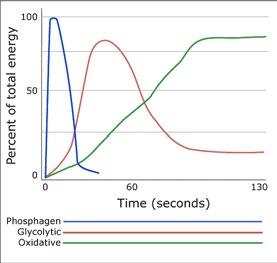

In recent years, the peer-reviewed literature has highlighted the positive correlation between horizontal force and maximum running velocity (Brughelli, Cronin & Chaouachi, 2011), challenging the use of exercises such as the front or back squat that have a greater focus on improving an athlete’s ability to generate vertical force. It is believed that horizontally-directed forces are important for sprinters to facilitate accerleration and in overcoming friction and wind resistance (Mero, Komi & Gregor, 1992).

In response to these findings, the barbell hip thrust has become an increasingly popular exercise that builds strength in the gluteus maximus, hamstrings and quadriceps, where

the force produced by the athlete is in a horizontal (anteroposterior) direction.

In 2017, the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research published one of the first longitudinal randomized controlled trials comparing one group of adolescent males performing a six-week squats program to another group performing a six-week hip thrust program. A range of performance variables were assessed, with the results indicating that improvement in the 10 and 20 metre sprint times may have been greater in the group undergoing the hip thrust program than in the squats group (Contreras et al., 2017).

9

The Study - Contreras et al. (2017)

The Objective

This study aimed to compare the effects of a six-week hip thrust and six-week front squat training programs on a range of performance indicators. Of particular interest to athletics coaches, the study examined the effect of the programs on 10 and 20 metre sprint times, horizontal jump distance and vertical jump height.

“Anteroposterior-resisted movements (hip thrust) appear to better transfer to horizontal-based activities (20m sprint)”

The Participants

All participants studied were male and between the ages of 14 and 17.

The Results

There was a positive effect of the six-week hip thrust training program on reducing 10 and 20 metre sprint times. There was also improved horizontal and vertical jump performance, although the authors noted a weak effect size.

When comparing the two treatment groups, the authors noted a "possibly [greater] beneficial effect" of the hip thrust training program compared to the front squat program.

The Limitations

1. Adolescent males going through puberty are in a unique physiological situation, so the results may not be applicable to females and older or younger athletes.

2. All participants had at least one year experience with squats but no previous experience of hip thrusts. This may have affected the rate of improvement.

3. Some critics have questioned the use of front squats, where back squats are more commonly used by current coaches for improving speed.

10 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

Front Squat Effect Sizes

The front squat group showed very likely improvement in vertical jump distance and a positive effect on horizontal jump performance. Effect size on 10 and 20 metre sprint times suggest front squats are "unlikey beneficial."

Hip Thrust Effect Sizes

The hip thrust group showed significant improvement in the 10 metre sprint and a strong effect size for the 20 metre sprint. There was also some support for horizontal jump and vertical jump improvement.

An analysis of between-group effect sizes showed that there was some evidence to support the hypothesis that 10 metre and 20 metre sprint times improved more among the hip thrust group than the front squat group. The authors noted the potentially beneficial effects worthy of further research.

*The 90% confidence limits represent the "likely range of 'true' effect sizes" and should not be interpreted to indicate statistical significance

-0.5 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 Vertical Jump Horizontal Jump 10m Sprint 20 Sprint Effect Size

-1.5 -1 -0.5 0 0.5 1 1.5 Vertical Jump Horizontal Jump 10m Sprint 20 Sprint Effect Size

Group Effect

Between-

Sizes

Figure 3: Effect sizes on performance indicators between treatment groups. (*90% conf. limits)

-0.5 0 0.5 1 1.5 Vertical Jump Horizontal Jump 10m Sprint 20 Sprint Effect Size

= Greater improvement in Squat Group

= Greater improvement in Hip Thurst Group

Figure 1: Improvement in selected performance indicators in the front squat group (*90% conf. limits)

Figure 2: Improvement in selected performance indicators in the hip thrust group. (*90% conf. limits)

HIP THRUSTS FOR SPRINTING

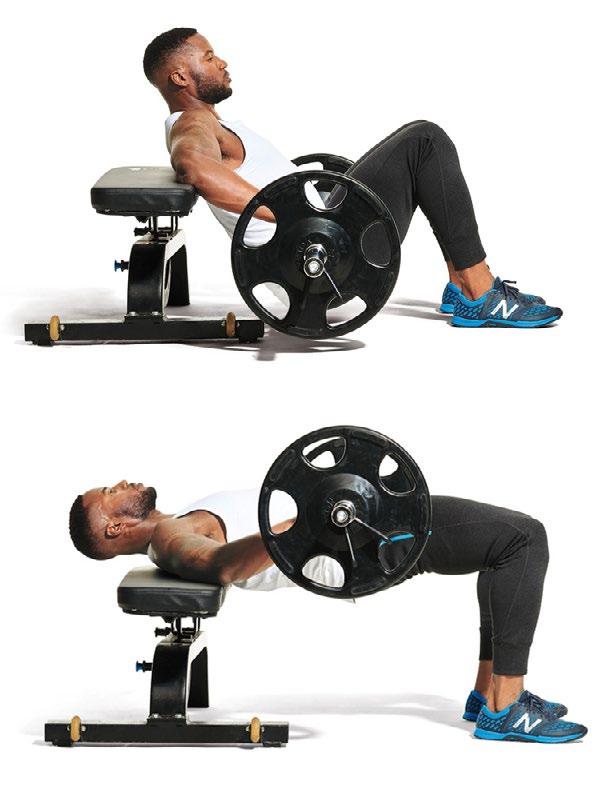

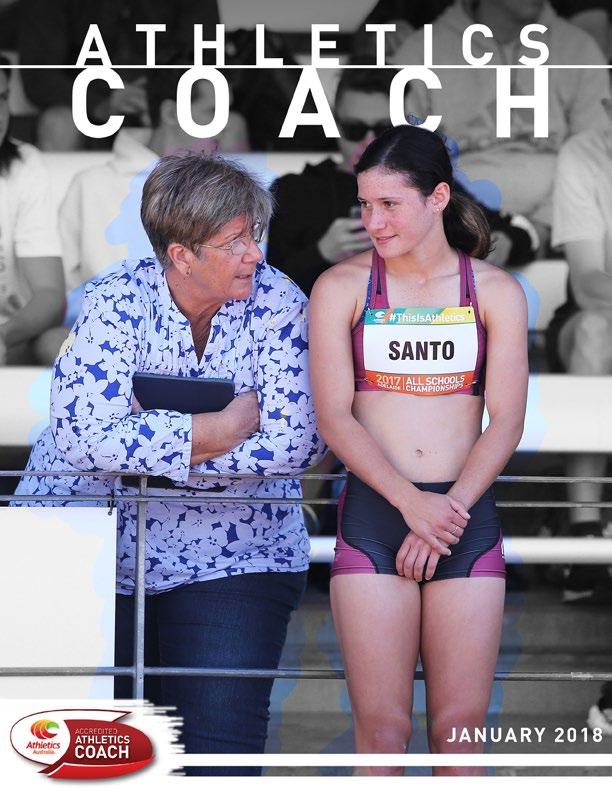

Above: Starting Position

(Credit: Sheer Strength Labs)

Below: Extension Position

12

How to Perform a Hip Thrust

1. Have the athlete sit on the ground with straight legs and their upper back resting on a padded surface, such as a bench or step. Position the barbell over the shins.

2. Ask the athlete to roll the barbell over their thighs so it rests directly across their hips, slightly above the pelvis. The barbell should be padded to prevent bruising and held with the palms facing down.

3. The athlete should now get into the starting position for this exercise (above image). Feet should be shoulder width apart and should be brought towards the buttocks to create a ~90 degree angle with the thighs.

4. The athlete raises the barbell off the ground by contracting the hip extensors. As the hips raise the athlete's back will hinge around the surface that they are resting on. It is critical that the athlete maintains a 'neutral' spine and pelvis and that the extension movement is derived from the hips.

5. The athlete should continue until full extension with the shins vertical and the body flat from knees to shoulders. Hold for one second before slowly returning to the start position for the next set.

Load: It is advised that beginner athletes first perform the movement without any additional weight until they have mastered the technique. Weights can then be progressively added.

Contreras, Cronin & Schoenfeld (2011) advise that intermediate athletes work their way up to loading equal to their body weight and that advanced athletes can reach weights of over 200kg after several months of progression.

13 HIP THRUSTS FOR SPRINTING

The Argument Against Hip Thrusts for Sprinting Performance

While the Contreras et al. study has opened the door on the possibility of hip thrusts becoming a crucial tool in the sprint coach's kit, other recent research has had less success demonstrating that hip thrusts can improve sprinting performance. Bishop et al. (2017) examined the effectiveness of an 8-week barbell hip thrust strength program in comparison to a control group, and found no statistically significant improvement in sprint times across any of the distances studied (10, 20, 30 and 40m). The authors concluded that although there was an increase in the athletes' hip thrust strength, this does not transfer into improved sprinting performance.

One possible explanation for the results of the study conducted by Bishop et al. was that

the loading was inappropriate for improving sprinting performance. For sprinters, the gluteus maximus needs to be able to produce explosive strength to perform high-velocity contractions (Mero, Komi & Gregor, 1992; Seitz et al., 2014). Hip thrusts with high weights are therefore likely to improve power in the gluteus maximus (supported by the observed increase in hip thrust strength) but would be less likely to increase the explosive strength required for sprinting. While further research is required, coaches should keep an eye out for future studies that examine athletes using a lighter load to encourage faster bar speed to better develop the explosive strength required for improved sprinting performance.

What are your thoughts on using hip thrusts for improving your athlete's speed?

Further Reading

Comfort, Bullock & Pearson (2012). A Comparison of Maximal Squat Strength and 5-, 10-, 20-Meter Sprint Times, In Athletes and Recreationally Trained Men.

Published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, this study found that maximal squat strength was significantly correlated with faster 5 metre sprint times in recreational and trained athletes. However, 10 and 20 metre sprint times were only found to be correlated with relative squat strength of the recreationally trained group.

The authors concluded that relative squatting strength is an important determinant of a successful start for all athletes.

Share your thoughts with the Australian coaching community.

Chelly, Fathloun, Cherif, Amar, Tabka & Van Praagh (2009). Effects of a Back Squat Training Program on Leg Power, Jump, and Sprint Performances in Junior Soccer Players. This study examines the effecitveness of a back-squat training program on increasing the sprinting and jumping performance of junior soccer players. The results indicated significant improvement in sprinting time and jumping force. The authors concluded that back half squats are highly recommended as part of training for junior players.

From an athletics perspective, these results may be transferrable to specific events and coaches of combined events athletes are especially encouraged to consider the results.

14 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

Paul Pearce on Hip Thrusts and Strength

For Sprinters

As a former 400m National champion and the current National Junior Sprints Coach and National Junior Coaching Coordinator, Paul Pearce advocates the use of hip thrusts for improving sprinting performance. We had the opportunity to speak with Paul about his strength program and understand why he sees hip thrusts as an important component of his training regimen.

Athletics Australia: Why do you use hip thrusts as part of your training program?

Paul Pearce: Essentially what it's trying to do is, in the first 20 metres, you want a good forward drive through the hip flexors, the glutes. The hip thrusts, when they're done right, is to make sure that everything is squeezing and projecting forward in the same motion that we are looking for on the track.

AA: What level of importance do hip thrusts have in your strength program?

PP: Hip thrusts are one of many exercises I employ, I wouldn't look it as the be and end all of the program. One of the things I commonly see that athletes do incorrectly is that they don't support the back well enough and develop lower back issues if they aren't doing it correctly. Without the proper support and exercises around it, hip thrusts may do more damage than good.

AA: What are the factors that you consider when determining loading in the gym?

PP: Each athlete needs to have an introduction to the exercise to ensure that they are doing it right all the way through. For me, when I'm with the athlete they need to be squeezing the glutes and making sure that they're on, rather than just doing the exercise for the sake of doing it. It's the same with anything in the

gym, the athlete's need to start with a small weight and learn to perform the movement correctly and big weights should only be for those that handle it.

"They need to be cautious - the same as with any exercise. They need to be doing the right movement pattern first before you add load"

AA: So you agree with Contreras that for beginners, hip thrusts can be completed just using the body weight of the athlete?

PP: Yeah definitely, definitely from a younger athlete's point of view or if an athlete is new to the gym environment. They need to be cautious - the same as with any exercise. They need to be doing the right movement pattern first before you add load.

AA: At what age would you start using this exercise with your athletes?

PP: There's not much difference between a simple bridge, which all of my younger high school athletes do as part of their warm up. They're doing a single-leg bridge, double-leg bridge just to make sure that glute activiation is occuring before they start the session. I have no issue with them doing something like hip thrusts in the basic gym environment but it's about using approrpriate loads for the stage that they are at. You could have a 16-year old boy who has been in the gym for two or three years and could be quite confident in doing some of the movements, whereas you could have a 23 year old coming to the gym for the first time. So it's about knowing the athlete's training age and adjusting accordingly.

15 HIP THRUSTS FOR SPRINTING

"They're not getting the basic lifting patterns right so they're going into complex movements too early and too soon"

AA: Contreras also advocates for a very gradual progression when setting load for hip thrusts - do you also agree with this assessment?

PP: I do and I think it needs to be gradual. One of the things to consider is that if you put too much weight on at one time the athlete may be unable to handle it and their technique will suffer. This could result in worse outcomes. Whatever we're doing in the gym needs to be able to be replicated on the track. It's not just about going out there and trying to smash it in the gym, whatever we do needs to be transferrable to the track or otherwise it's not relevant.

AA: Going back to your explanation for why you use hip thrusts - creating horizontal force, are there any other exercises that you use to achieve that?

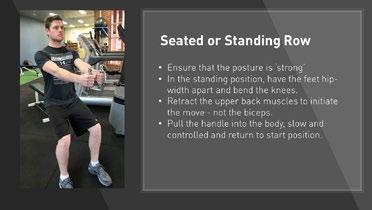

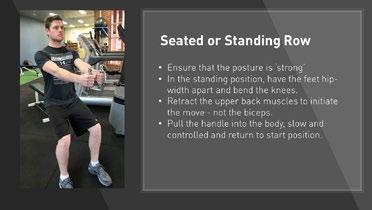

PP: I'm a big fan of single-leg squats, stepups, anything to do with the glutes, hamstrings and stabliser muscles around the side. I do an exercise similar to a hip thrust, where we are standing up and working on the hip flexors, glutes and hamstrings while ensuring that the core is engaged and remains in a stationary braced position. It's essentially a replication of the running motion in the gym that can be done with cables or with a machine if you have that in the gym.

Anything along the lines of single leg exercises are, for me, a big thing. It means you're targeting the specific side that might be weaker than the other, and the coach can tell straight away if a hip drops either way

whereas during double leg exercises they tend to stay fairly stable even if one glute or hamstring is working harder than the other.

AA: What's the most common error that you see working with sprinters in the gym?

PP: I guess, talking about the developmental space, is athletes just not getting the simple stuff right. They start adding complex movement patterns in the gym when they don't need to. They're not getting the basic lifting patterns right so they're going into complex movements too early and too soon.

AA: What are the consequences of that?

PP: Incorrect technique, back issues, hip issues, whereas if you're getting it right early, your ability to move weights and move forces quicker later on becomes easier. You ask any athlete and when a lot of their lifts feel easy, they're doing the correct technique and it's all going up in the one motion. Whereas if the weight is off to the side or the hips are off it's going to be a struggle.

This is also where the transfer from gym to track comes into play. You might be working one side more and when you go to the track and try and recreate the forces in a fast and dynamic way, that's where something might happen such as a hamstring injury.

You're also not getting the right outcomes on the track because you're cutting corners in the gym.

The ultimate message is keep it simple in the gym and don't try and do complex movements too soon.

16 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

17 HIP THRUSTS FOR SPRINTING

SQUADS MY

At athletics and recreational running events across the country, we have been speaking with participants about how we can help connect them with Accredited Athletics Coaches. In addition to a more intuitive and user-friendly Coach Search system, one of the most requested features was a means for athletes and runners to easily find active running and track and field squads in their area.

To meet this demand, we have created a new service for coaches to create unique pages for their squads that will link directly from their coach profile. Athletes will also be able to search directly for squads that meet their needs through the Squad Search system that will be made publically available from the end of the month.

For coaches, setting up your squad page is a quick and simple process. Once complete, it will assist athletes and recreational runners find your group and serve as another opportunity to link your website to improve your SEO and promote your services to the wider public.

This is a free service for every Accredited Athletics Coach.

18 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

Step 1

Login to the Coach Portal. If you have forgotten your password click here

Step 3

Select ‘Add a New Squad.’

Step 2

Select View/Add Squads.

Step 4

Complete the digital form, including the club name, location, squad type, athlete or runner skill levels catered, website, contact details and a blurb.

Select ‘Save’ at the top of the screen when you are finished.

Step 5

You will now be taken back to the ‘My Squads’ page. From here you will be able to edit the squad you have just created, add an additional squad, or delete a squad that is no longer relevant.

19

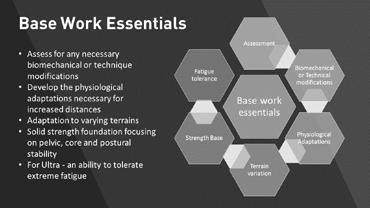

Horses for Courses

Finding the Right Goals for the Right Runner

Written by Tim Crosbie

Written by Tim Crosbie

Picture my Grade 6 teacher Sister Margaret… hammer in one hand and screw in the other, furiously belting the screw into the wall but with each strike gaining no traction. While obvious to even a 12 year old student that either a screwdriver or a nail were better choices, Sister Margaret’s apparent lack of experience resulted in an entertaining spectacle for the students, and a frustrating few minutes for Sister Margaret!

But as with many things learnt early in life, the lesson of what may be obvious to some isn’t necessarily obvious to others, has stuck with me since that day.

What’s this got to do with coaching?? Well in many instances I’ve found that when dealing with novice runners, how they approach their initial foray into the sport and go about goal

setting and training methods, often leaves you scratching your head. Dealing with this is one of the true tests of a coach.

Whilst we celebrate the dramatic growth in recreational running over recent years, increasingly the power of social media seems to be skewing the landscape and the ‘further the better’ mentality has well and truly taken hold. If not for parkrun resetting some mindsets, I’ve no doubt we’d be in the midst of an ultra marathon revolution and dealing with the inevitable consequences.

So let’s look at some key things a coach should consider when having those all important initial conversations concerning background, where they want to go and how they are going to get there.

ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018 20

"Dealing with novice runners, how they...go about goal setting and training methods...is one of the true tests of a coach."

DEVELOPMENTAL AND TRAINING AGE

The athlete’s age will be a primary consideration in determining appropriate distances and events. Generally, in Australia we consider the minimum age for longer events to be the following. 10km -12 years, Half Marathon – 16 years, Marathon and Ultra – 18 years. 10km & below – year 1 of training, Half Marathon –years 1 to 2, Marathon & Ultras – years 3 to 4.

WORKING ON THE STRENGTHS

Often the athlete will have a pre determined bias based on their previous experience or where they believe that their strengths lie. However, in many cases a coach will identify something that indicates a new direction for the athlete. Convincing them to take the new path becomes the next challenge!

Distance is an obvious one to consider here. It can be quite frustrating for a coach to have a good 5 or 10k runner who won’t get out of bed for anything less than a half marathon. In reality, working on their 5 or 10k lays a great foundation for stepping up - but often the progression is accelerated before a solid foundation is established.

These are suggested minimums and there will always be exceptions due to individuality. And of course, parental influence can muddy the waters. However, applying these limits will have the coach steering a steady course for a developing athlete.

We must also consider training age for recreational runners with the number of late adopters presenting a new dynamic for coaches dealing with mature bodies that may have low training history. For the recreational runner we can introduce another set of guidelines for when distances are appropriate:

A coach may also spot either a stylistic or mental strength suited to particular events. When looking for a good mountain runner, it's not the beautiful stride pattern of a track runner that will have them climbing 1000 vertical metres, more the combination of total body strength and a steely resolve.

"Working with cadence can deliver some degree of change"

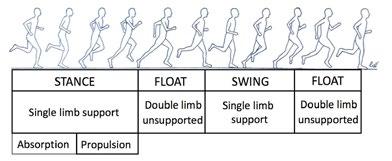

CADENCE / STRIDE PATTERN

All athletes have their individual stride pattern and cadence when running. This will naturally predispose them to certain events. The steady rhythm and turnover of a track runner will be ideally suited to road racing, while the strength of a cross country runner will lead them to also excel on the trails or hills.

Once again these are guidelines only, but taking a more conservative approach to distance graduation tends to lead to lower injury risk and greater longevity as a runner.

Whilst changing a runners natural style is problematic, there is no doubt that working with cadence can deliver some degree of change as will be demonstrated in the case study later on in this article.

Distance Biological Age 10km and Under 12 Years Half Marathon 16 Years Marathon and Ultra 18 Years Distance Training Age 10km and Under 1 Year Half Marathon 1-2 Years Marathon and Ultra 3-4 Years 22 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

MENTAL STRENGTH + CONCENTRATION

Coaches quickly get to understand the psyche of their athletes and the varied range of both mental strength and the level to which they can stay switched on during competition. The latter can dictate event selection for many, particularly on the track where mental concentration is paramount in race tactics, pace regulation and decision making.

As a competing athlete myself, for the 4 minutes of a 1500m I could lock in and be in total control, the 8min+ of a 3000m was possible but a stretch, while the 15min required for a 5000m was beyond my capacity.

It is often in training that a coach will see these patterns develop. Can the athlete sustain 8 x 1km without missing a beat or do they thrive when presented with a set of 6 x 400m?

PHYSICALATTRIBUTES

We have to be careful not to pigeon hole athletes based on their physical dimensions, as we can all name many ‘exceptions to the rule’. The 200cm and 90kg mile runner may look out of place on the start line, however is that an impediment to success?

However, what you’re dealing with in terms of body shape, height, weight and muscle distribution can be a key indicator of what your runner may be best suited to. Guiding your runners on their personal journey will require a understanding on how the factors outlined above impact them and what strengths or weaknesses the runner and coach want and need to work with.

Laying the ground work from the start can be as simple as a statement such as ‘we don’t yet know what you’re best at and the exciting next phase of your journey is to find out’.

And perhaps if Sister Margaret had have had a carpenter guide her through some basic maintenance tasks then those entertaining few minutes of frustration may well have been avoided.

23 HORSES FOR COURSES

"A low centre of gravity meant that Kirstin would never look like a gazelle when running, so on the advice and under the supervision of her Physio Peter Malliaris, the increase in cadence was affected in a matter of months"

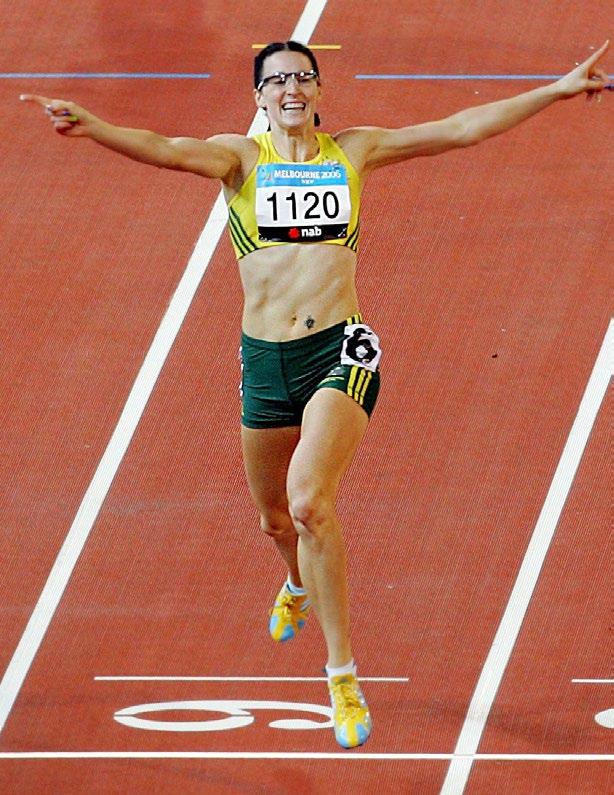

CASE STUDY - KIRSTIN BULL

In 2008, Kirstin Bull averaged 5:13 per km to run 1:50 for her first half marathon. Her goal when she commenced a formal coach/ athlete relationship was to improve her half marathon time and maybe one day run a marathon. Eight years later Kirstin averaged 4:32 per km on her way to winning the World 100km Road Running Championship, and in doing so broke her own Australian record.

What were the indicators during the intervening years that pointed Kirstin towards ultra marathons and in particular the 100km road race?

Two key factors presented early with Kirstin;

1. a short body with relatively low centre of gravity & 2. a mental resolve rare even amongst ultra marathon runners. The first factor meant that as a competing athlete her 5k/10k performances were always going to be modest in comparison to the marathon and beyond. The second factor gave us the raw material and desire to push the limits of training and present new training concepts that many would baulk at.

Race management then became the next consideration as the plans for her ultra career took shape. With her first forays into ultras being on the trails with some wins in

the 56km Two Bays Trail race and a surprise Bronze medal at the Commonwealth Trail Running Championships over 70km, her aptitude for distance was apparent, but both athlete and coach knew her next, and more successful phase, would be on the road.

Despite being good on the trails, a comparison of shorter road and cross country races indicated that Kirstin really is at home on a reliable surface where her cadence remains relatively steady and she can lock into pace. This really became evident as she set about winning the 44km Great Ocean Road Marathon for three successive years.

Technically there was only one change in the final phase of development that delivered tangible benefits…. lifting her cadence from the mid 180s to 200. A low centre of gravity meant that Kirstin would never look like a gazelle when running, so on the advice and under the supervision of her Physio Peter Malliaris, the increase in cadence was affected in a matter of months.

So through a combination of observation, experimentation, careful management and one key technical adjustment, transforming a recreational runner into a World Champion was an eight year project that neither athlete or coach would ever have believed possible at the start.

24 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

25 HORSES FOR COURSES

THE HIGH PERFORMANCE VEGAN ATHLETE

NEW RESEARCH SHOWS IT IS POSSIBLE

Originally published by The Conversation

Veganism is a life choice that more people seem to be making. Still, despite its increase in popularity, when most think of a vegan, they tend to think of an animal rights activist, or someone who is a bit of a hippie at heart. And most likely, said vegan is slightly underfed owing to a strict diet of tofu, lentils and salad.

But despite the stereotype, over the last few years, more and more sports stars and wellknown athletes have also made the decision to go green and follow a vegan diet. And with reports that two vegan seafaring brothers are preparing to cross the Atlantic, fuelled purely by a diet rich in lentils, soya beans and vegetables, it seems being vegan and wearing a woolly cardigan no longer go hand-in-hand.

If successful, the British brothers who plan to live off a diet of freeze-dried meals on their 3,000-mile vegan voyage will become the first to row the crossing on a plant-based diet. But while veganism is now somewhat in vogue, concerns have been raised that a diet which restricts meat, fish, and dairy can’t possibly be good for your health.

Plant Power

Vegan diets can make getting sufficient calories difficult – particularly if energy

David Rogerson Senior Lecturer

David Rogerson Senior Lecturer

University of Bath

I am a senior lecturer in Sports Nutrition and Strength and Conditioning, and currently lead Sheffield Hallam University's MSc in Applied Sport and Exercise Science.

expenditure (the amount of calories we burn) is high. And for athletes who undertake lots of training this could be a problem. This is why in my latest paper, I set out to find out if a vegan diet really can provide an athlete with everything they need to perform at an optimum level. And my findings certainly provided food for thought.

Previous research shows that vegans may end up consuming less protein and fat than non-vegans, and may struggle to get enough vitamin B12 – which is found in meat, fish and dairy. B12 is an important vitamin, and a lack of it can lead to anaemia, weakness and mood changes.

Studies have also shown that a vegan diet can be low in Omega-3 fatty acids which come from nuts, seeds and fatty fish (like salmon), along with calcium (think milk, and cheese) and iodine, which is also found in dairy products. But plant-based diets also tend to be higher in carbohydrates, fibre and other important vitamins and minerals too

26 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

“Through the strategic selection and management of food choices, and with special attention being paid to the achievement of energy, macro and micronutrient recommendations, along with appropriate supplementation, a vegan diet can achieve the needs of most athletes satisfactorily.”

- Rogerson (2017)

27

For an extreme challnge such as crossing the Atlantic - which is going to result in a very high energy expenditure – obtaining sufficient calories is going to be a high priority. My research shows that vegan diets tend to be high in fibre which helps you to feel full, so finding ways of consuming enough calories without getting so full that you can’t eat enough is important. Eating energy-rich snacks like nuts and dried fruits is one way to do this, as is increasing feeding frequency.

The Question of Protein

Protein is necessary for healthy skin and muscles, and is important for athletes in terms of recovery from exercise. But getting enough protein on a vegan diet is less of a concern than you’d think, especially if enough calories are consumed. While it has been suggested that vegetarians and vegans might need slightly more protein than omnivores – due to plant-based sources being harder to digest – the main concern for the rowing brothers will be ensuring they eat a range of protein-rich foods daily.

Organic compounds called amino acids are the building blocks of protein – found in all protein foods like meat and pulses – though many plant-based protein sources tend not to contain all the essential amino acids. But

Further Reading

Tarnopolsky, M. (2004). Protein Requirements for Endurance Athletes.

This review article examines the protein requirements for endurance athletes at low, moderate and high intensity exercise. The author concludes that at low and moderate intensities there is no increase in dietary

a vegan diet can obtain all essential amino acids, in sufficient quantities, if the diet is varied and energy appropriate. Pulses – such as beans, lentils, peas – and grains – like rice, oats, wheat – are all protein rich, with complementary amino acid profiles. And eating a range of these foods throughout the day will ensure protein and amino acid needs are met comfortably.

With energy and protein covered, the next main concern of a vegan diet is getting enough micronutrients – so checking off the vitamins and minerals. While vitamin B12 can be supplemented with a daily tablet or injection, other nutrients such as calcium, iron, zinc and iodine can be easily managed with careful meal planning. Foods like flax seeds and walnuts are also important essentials of a vegan diet as they are a good source of omega-3, along with algae supplements, which may help to control inflammation and improve recovery. Clearly then being vegan and an athlete can go hand in hand, but it does take careful planning.

So for the brothers crossing the Atlantic, who will have to put up with wild winds and stormy seas on a near daily basis, it seems getting enough plant power is going to be the least of their problems.

protein requirements.

The author suggests that elite endurance athletes have higher protein requirements but suggests that supplementation is unnecessary, with enough energy and dietary protein coming from a mixed diet.

28 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

Diet Type Possible Dietary Issues

Omnivorous Poor ad libitum diets can lead to nutrient deficiency.

Vitamin D deficiency possible (if sun exposure is poo/unlikely).

Possible Sport Related Issues Recommendations

Male and female athletes with low energy intake at risk of nutrient deficiencies.

Calcium requirements increased during negative energy balance, amenorrhea and female athlete triad.

Energy intake should be scaled to the activity level.

Depending on the sport, 1.4-2.0 g kg-1 CHO; 0.5-1.5g kg-1 fat (or, 30% energy) consumed daily.

Micronutrient-rich diet sufficient to achieve DRVs; Vitamin D3 supplement might be necessary.

Pescovegetarian

Same as omnivores plus:

Energy and protein deficiencies.

Lacto-ovo vegetarian & Lactovegetarian

Vegan

Same as pescovegetarians plus:

Long chain n-3, iron, zinc, riboflavin deficiencies more likely.

Same as above plus:

Protein, fat, n-3, B12, calcium, iodine deficiencies also possible/ likely in males and females

Iron deficiency with and without anaemia a risk in female athletes.

Same as omnivores, plus ensure that iron needs are met via a variety of food sources.

Same as pescovegetarians plus:

Reduced muscle creatine and carnosine stores a possibility in males and females.

Same as above plus:

Low bone-mineral density is an increased possibility in female athletes.

Achieving energy balance might be a problem for larger athletes.

Same as pesco-vegetarians plus:

EPA/DHA supplement might be needed.

Increase iron (m=14mg & f=33mg day-1) and zinc (m=16.5mg & f=12mg day-1) intakes due to reduced bioavailability of plant sources.

Same as above plus:

Increase protein to 1.7-2.0g kg-1 and up to 1.8-27 g kg-1 during weight loss phases (obtain from range of plant based foods).

Nuts, seeds, avocados, oils to achieve 0.5-1.5g kg-1 fat daily.

EPA/DHA (microalgae); vitamin d3 (lichen) & B12 supplements might be needed; iodine in some instances too.

1000mg day-1 calcium from beans, pulses, fortified foods and vegetables.

29 THE HIGH PERFORMANCE VEGAN ATHLETE

Rogerson, D. (2016). Vegan Diets: Practical Advice for Athletes and Exercisers.

IN SPORTING SCHOOLS

FUNDING OPENS Visit the website to learn how your school can apply.

IAAF KIDS' ATHLETICS

TERM 2

ATHLETICS SCHOOLS OPENS MARCH 5

31

Anyone who loves running and the beach will be able to tell you that putting the two together is one of the most beautiful ways to spend an early morning or sunlit afternoon - but it can also be a bloody tough session! A study by Lejeune, Willems & Heglund (1998) found that running on sand requires 1.6 times more energy than running on a hard surface primarily due to a decrease in the muscle-tendon efficiency. This has been shown to allow runners to perform sprint sessions at maximum intensity with higher energy expenditure and greater metabolic power values (Gaudino, Gaudino, Alberti & Minetti, 2013).

In addition to the extra force being generated by the runner, running on sand requires a greater range of motion of the ankles and hip flexors that may increase strength and flexibility (Pinnington, Lloyd, Besier & Dawson, 2005). It has been claimed that running on sand also reduces stress injuries as a result of the reduced impact from running on a softer surface.

These benefits have led to some popular running websites to claim that beach running is a great way to improve strength, fitness and running performance while preventing injury. So let's have a look at what the peerreviewed evidence says, in conjunction with the opinion of our running experts, on the veracity of these claims.

Testing Three 32

for Injury Prevention

Running on Sand Prevention and Performance

Common Claims About Running on Soft Surfaces 33

Three

Claim 1

"Running on Sand Is a More Intense Workout Than on a Hard Surface"

What does the Peer-Reviewed Literature Say?

Multiple studies support the claim that running on sand requires the runner to expend more energy than running on hard surfaces.

Lejeune et al. (1998) found that running on sand required 1.6 times more energy than running on hard surfaces.

Pinnington & Dawson (2001) found that sand running required 1.5-1.6 times more energy than on a grass surface.

Muramatsu et al. (2006) found that jumping required 1.2 times more energy on sand than on a solid surface.

From these findings, Gaudino et al. (2013) concluded that running on sand is an effective way to perform sprint training with greater energy expenditure and higher metabolic power values than could be achieved training on solid surfaces.

What do the experts say?

"Of course, it all depends on the effort and the program, but it is true that a session of equal distances would require more effort on sand" says sand running expert Greta Truscott. "I coach soft sand every week and I've raced on soft sand and it's an amazing cardio workout, which is why it's so good."

Trail runner Jane Kilkenny agrees, but points out that "running on sand has a different muscle demand" so the requirements are "not completely comparable to running on hard surfaces."

What are the coaching implications?

For coaches, this tells us that distances need to be adjusted appropriately to ensure that we are targeting the correct energy systems and working within the athlete's ability. Reducing distance by ~35% is a good general guide for sprint sessions (remember that acceleration is especially difficult on sand), while endurance running can be adjusted by setting a time objective rather than distance target. Beach running is also a great option for Fartlek sessions where runners are able to adjust the pace according to how they are feeling and change how they run in conjunction with environment - for example, faster sections over the harder sections of beach and slower periods over the softer sand. However, soft sand sessions allow for lots of variety; "you can do everything you can do on a track or on the road; fartlek, sprints, hill sessions on the dunes etc... sand running can be an intense full body workout" Greta says.

Shoes or Barefoot?

Going barefoot is one of the factors that many runners find appealing about training on the sand, but Greta Truscott advises a gradual approach to barefoot running. "With new runners...maybe in the last 5-10 minutes of the session, have them take their shoes off and get them used to running barefoot. Then in future sessions you can slowly increase the time they spend without shoes and ease the runner into it." In addition to the extra strain on the ankles and lower body, coaches should be aware of the risk of cuts and bruises, especially when running on coarse sand and advise their runners to cover any pre-existing cuts or blisters.

Getting to Know

Truscott ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

Greta

BEACH RUNNING

Claim 2

"Running on Sand Builds Strength in the Lower Body That Running on a Hard Surface Does Not"

What does the Peer-Reviewed Literature Say?

There has been a lack of peer-reviewed studies that have shown that training on sand develops muscles that training on a hard surface does not. However, there have been studies that show that running on sand works some muscle groups in the lower body more intensely than training on a hard surface.

Yigit & Tuncel (1998) showed that in a comparison between a control group and runners on hard and soft surfaces, the runners in the sand group had a greater increase in calf circumference over the six-week endurance program. This suggests that sand running may be associated with greater overload in that muscle group than hard surface running and no running.

Pinnington et al. (2005) identified a greater activation of the gastrocnemius of runners when running on sand than a harder surface.

What do the experts say?

Greta Truscott: "I can tell from my own running that it definitely strengthens my calfs, quads, hamstrings and glutes...even the abs get a good workout because you're bracing your core for stability. Running on soft surfaces is like a strength session in itself!"

Tim Crosbie: "It's especially useful for cross country runners, building strength in the ankle and preparing for running on uneven surfaces that they might encounter. It's also good for runners preparing for races such as the "Big Red Run", getting them used to the surface and building the specific strength that's required for running on softer surfaces.

Jane Kilkenny: "It places more stress on the calves and particularly the achilles...sand hills can also be a great way for coaches to build strength in the runner's hips and core.

What are the coaching implications?

Running on sand can be a good addition to the training program for runners looking to build strength in their lower body, core or hips. However, coaches should remember that strength is specific and therefore need to consider whether the benefits of the muscle gained from beach running are relevant to the objectives of the runner.

For Rejoov Runners' Greta Truscott, running on softer surfaces isn't just 'another' training session but a lifelong passion. Growing up in central Australia, Greta speaks fondly of her time running in the soft sand of the creek beds. "Running on the sand...you definitely feel liberated. You've got beautiful scenery...it's uplifting and refreshing, especially running barefoot." Today, Greta and her partner Chris are based on the on the beautfiul Sydney coast and soft sand running is a key part of their training program. "It's great being able to run into the water between sets or dive in and catch a few waves at the end of a session - that's a big part of what we do." For more information about Rejoov Runners, check out the website

Claim 3

"Running on Sand has a Lower Injury Risk than Running on Hard Surfaces"

Evidence of Higher Injury Occurence

Knobloch, Yoon & Vogt (2008) found that among masters athletes, there was an increased risk of mid portion achilles tendinopathy when running on sand when compared to running on ashphalt.

Richie, de Vries & Endo (1993) found that running on sand was correlated with increased exercise induced medial shin pain.

Barrett, Neal & Roberts (1998) argued that the unstable nature of sand, especially dry sand, was likely to increase the risk of musculoskeletal injuries in an athlete's lower body.

Pen, Barrett, Neal & Steel (1996) showed that among elite Ironmen, running on sand was the component of training and competition that resulted in the most numerous and severe injuries of the calves, shins and knees.

What does the Peer-Reviewed Literature Say?

Studies that have examined the correlation between running on sand and injury occurence have found that running on sand increaases the likelihood of some injuries, while decreasing the occurence of other injuries compared to hard surfaces. However, further research would be required to determine whether the overall risk of injury increases or decreases with running on sand.

Evidnce of Lower Injury Occurence

Nigg & Segesser (1998) demonstrated that training on firmer surfaces resulted in a higher occurence of overuse injuries than softer surfaces. This was supported by Inklaar (1994) in a study of soccer players.

Ekstrand, Timpka & Haugglund (2006) found that among football players, impact-related injuries were also associated with harder surfaces.

Cressey et al. (2007) explored the possibility that unstable surface training, such as training on sand may improve balance, strength and mobility to reduce the risk of lower-limb injury in performance athletes.

Miller et al. (1998) showed that training on soft surfaces could potentially lead to lower levels of hemolysis (destruction of red blood cells) during exercise as a result of decreased forces occuring during heelstrike.

Ultimately, there is still a lack of direct causal evidence to suggest that running on sand results in a greater or lesser risk of injury than running on hard surfaces. However, there are some longitudinal studies currently being conducted that should be released this year that may shine further light on the effects of soft sand training for preventing injury among recreational runners and performance athletes.

36 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

What do the experts say?

Greta Truscott: "It does depend on the type of injury and the runner...as a general rule I'd say if it's an impact injury there's a lower chance because of the sand absorbing the force....[as for] instability injuries, you need to be really careful. Be considerate of the camber and uneveness of the sand."

Jane Kilkenny: "It depends on the injury...I wouldn't put anyone on the beach with a history of achilles inujries or ongoing issues with their ankle or knee. The sand can add an extra injury risk with the extra stability challenge, however sand training can be an excellent option to add variety and intensity to training sessions."

What are the coaching implications?

While more research is required before we can say definitively what the effect that running on sand has on injury occurence, exisiting research shows that the additional challenge to the lower body does increase the likelihood of certain injuries. Coaches should be aware of the medical history of their runners and use caution when planning soft surface sessions, especially for runners with a history of achilles issues. By contrast, runners who are particularly susceptible to impact injuries may benefit from the reduced forces experienced during running on softer surfaces. Runners coming to soft surfaces for the first time should be encouraged to gradually increase their loading to allow for adequate time to build the unique strength required for beach running.

Football clubs (such as the Sydney Swans pictured above) have used sand running during pre-season to reduce the risk of overuse injuries that are more likely to occur during the preseason period.

( Woods, Hawkins, Hulse & Hodson, 2002).

Beach running is an attractive proposition for people looking to get fit over the summer - but coaches should consider the additional risks of sand running for untrainied runners.

37 BEACH RUNNING

BEACH SESSIONS

If you decide that beach running is something you'd like to incorporate into your sessions, here are some popular ideas to get you started.

Long Run:

You can do your usual long run on the sand, but there are a couple of extra things to take into consideration. Firstly, every beach will have a slant and even if it is only very slight, this will put extra pressure on one side of your body, especially on your hips, knees and ankles. Planning your run as an out-and-back session will prevent the same side of the body taking the extra load for the full run.

For a long run, it's better to run in the wet harder sand to avoid putting too much stress on your ankles and achilles for a long period.

Zigzags:

This run uses the natural terrain of the beach to create a challenging interval session. After a light warm up, runners alternate between 1:30 to 2 minute periods running at an easy pace on the harder wet sand and 1 to 1:30 minute periods of intense effort on the softer sand higher up the beach.

Fartlek:

The natural change in the environment along a coast allows for perfect conditions for fartlek sessions. One possible suggestion for runners looking to add a unique flavour is to run as close to the water's edge as possible, following the tide as it moves up and down the beach without getting wet. This will naturally create periods of increased pace as the runner escapes the larger waves as they rapidly hit the beach.

Hills:

Sand dunes make for an intense hill session that aim to build strength in your hips and calves, while offering a tough cardio challenge. This is usually extra challenging as dunes usually have the softest sand on a beach, so you won't require as many reps as you do on a hard surface. Just be aware that dunes play an essential role in protecting the coastline and trampelling can destory the flora that helps keep dunes together. Be aware of local restrictions to keep off the dunes and avoid large groups using the same area.

38 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

Intervals:

For groups of varying abilities, the out and back time based interval variations are an excellent option that result in everyone back in the same spot for recoveries together. Greta Truscott recommends descending intervals or pyramid intervals. In addition, coaches can use a mix of short sprints, long reps, team relays and 'In and Outs', where runners go from touching the water with their hand or foot and racing up to the promenade or bank and then back to the water.

Pyramid Intervals Descending Intervals (x2)

30secs out easy, back strong, 30sec rest

1min out easy, back strong, 30sec rest

2mins out easy, back strong, 30sec rest

1 min out easy, back strong, 30sec rest

30secs out easy, back strong

2mins out steady, 2mins back quicker, 30sec rest.

1min out steady, 1min back quicker, 20sec rest.

30secs out strong, 30secs back quicker, 10sec rest.

39

"To be a great throws coach you need to have a great technical model, strong knowledge of strength and conditioning for power

ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

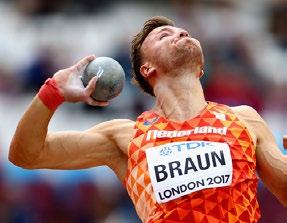

Damien Birkinhead, coached by Scott Martin, at the 2017 World Championships

model, great coaching eye and a power athletes"

COACHING THROWS WITH SCOTT MARTIN

Talented athletes don't always make great mentors, but Scott Martin has made a smooth transition from competing into coaching. A Commonwealth Games medalist in both the Shot Put (Bronze) and Discus (Gold), there is no doubt Scott was well equipped with a solid understanding of the technical model of the sport. However, his success as a coach has as much to do with his strong understanding of the events as the rigorous approach he takes to planning and the approachable attitude that he maintains with his athletes. Currently the National Junior Throws Coach in addition to his role as Personal Coach to (among others) Damien Birkinhead and Todd Hodgetts, Scott took the time to speak to us about the challenges of coaching throws at the various levels of the sport and hopefully encourage more club-level coaches to specialise in coaching the throws events.

Athletics Australia: What are the challenges of becoming a throws coach and why do you think therearefewercoachesatclublevelspecialising in throws than the other event groups?

Scott Martin: I could talk for a while about that... well, firstly it's a technical event and technical events are difficult to coach. There are four different throws and they're quite different in themselves so it's hard to specialise. Then the other big important component of throws is strength and conditioning, so to be a great throws coach you need to have a great technical model, great coaching eye and strong knowledge of strength and conditioning for power athletes.

41

“There’s nothing wrong with introducing strength and conditioning early as long as it’s done age appropriately considering [the athlete’s] developmental age”

SM: In addition, it's a bit harder to find as many athletes to coach. For example, with running there's a lot of events to keep people incentivised, there's gifts, club races, relays and everything, whereas with throwing it's a bit more limited so you get a smaller pool of athletes.

Just from a coaching point of view though, it's hard because of that requirement to have a strong strength, conditioning and technical understanding.

AA: So in your opinion, what should come first? Should a throws coach begin with that strength and conditioning background?

SM: It depends on the age group. Technical is more important for the younger athletes, so if you're coaching anyone up to the ages of 16 or 17 the technical is the most important component. After that then the strength and conditioning side of things becomes really important, especially for elite athletes.

AA: On the topic of age groups, when do you think athletes should begin specialising in the throws events?

SM: I started throwing when I was 13, you don't have to get in too early. Most good athletes in good systems - you'll find it's more appropriate to do multiple events and multiple sports for a long time, even up until the age of 18, 19. For example, it's good to have a Shot

Putter do Shot Put, Discus, Long Jump, 100m, High Jump whatever and also play Basketball or another sport as well. The more rounded you have an athlete the more skills they have and then they can specialise later with greater results. It's not like you have to do just Shot Put from the age of 12 to achieve success.

AA: And at what age do you think that the strength and conditioning training can come into the coaching program?

SM: Depending on how it's prescribed, you can have strength training such as body weight, medicine ball and to a small extent overweight or specific implements very young. When it comes to what we traditionally think of as strength and conditioning, like heavy lifting then you'd want to move into that around 16. It's hard, you've got to put a thousand disclaimers when you're talking about strength, but it depends on the kid as well. You've always got to consider the individual and their physique, some kids are just naturally quite strong whereas others you need to be careful and introduce strength slowly to avoid injuries or overworking them.

But there's nothing wrong with introducing strength and conditioning early as long as it's done age appropriately considering their developmental and training age. And that it's done in a way to build them up and not burn them out.

ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

Shot Put Basics

From Run! Jump! Throw!

• Shot resting on the fingers and base of the fingers

• Shot placed at the front part of the neckthumb to the collar bone

• Fingers spread around the shot

• Power position - body is low ready to drive up through the legs

• Body well balanced with head and arm back preparing for release

• Hips and shoulders are twisted

• Throwing arm is at a ~90 degree angle to the trunk

• Elbow turned and raised in the direction of the throw

• Speed coming from the legs to release the shot

• Opposite arm bent and fixed close to trunk

• Palm of throwing arm faced outwards with the last point of contact with the shot coming off the tip of the fingers

• Head is behind the bracing foot until release

43 COACHING THROWS

AA: You mentioned the benefit of having your athletes compete in a wide range of throws events - is there any particular order you think that they should be introducted?

SM: It doesn't really matter - the only one that I don't always recommend for the younger guys is javelin, because there is quite a high injury risk for an athlete that isn't particular good at it. If they've got a good throwing motion javelin is good, otherwise Shot Put, Discus or Hammer are all helpful and transferable.

For most of our athletes, Shot Put and Discus works together really well and of course sprints and jumps are really good for throwers. Distance events less important, you won't find many throwers who enjoy running 3km, but sprints and jumps are important in addition to the throws.

AA: Is there anything that you have found from your experience that encourages athletes, especially during their teenage years, to stay involved in the throws events?

SM: Success is the big one...Success and a really good training squad I think is pretty important. So, there are quite a few good squads around the country where there are a lot of athletes of different ages training together... so when you go to training it's a bit more fun and relaxed because you've got a few friends there that make you want to go to training and everyone's throwing at their own level. If you can create a great squad atmosphere with five to fifteen athletes all training together it's always good. In our training squad we've got athletes from 14 through to 26 years old, so there's a good mix of ages with older athletes for the younger guys to look up to and learn from and the older guys can benefit from the leadership position.

If people are having fun at training, because that's most of what we do, they're probably going to stay in the sport longer and have a better chance of having success and continuing on.

44 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

45 COACHING THROWS

Accredited Coach Graeme Watson shares his experience bringing athletics to the outback as part of the 'Carey Right Track' program.

On Sunday 1st October a Carey Right Track Foundation team comprising of athlete/coaches from Canning Athletics Club and Carey Baptist College staff and students travelled 9 hours north of Perth to Meekatharra. Together with members of the Meekatharra community they would spend the next week running the inaugural Future Leaders Athletics Mentoring Experience - FLAME.

For several years the foundation has run school athletics clinics to build trust and connections with rural, remote and indigenous communities. Over the last 18 months the connections built through athletics have blossomed into a close partnership with Meekatharra. This partnership has provided opportunities for young people to learn athletic skills, empowered older people to

develop coaching skills and facilitated deep friendship between the two communities. These friendships have been solidified through staying in each other’s homes when travelling for athletics commitments.

FLAME was created in partnership with members of the Meekatharra community when they asked for the foundation’s support to “get the young people out of town over the school holidays so they don’t get in trouble.” The team behind FLAME included Mission Australia, Yulella and Youth Mental Health in Meekatharra and the Carey Right Track Foundation. Financial support was received from Athletics Australia’s, “Athletics for the Outback Program” and private sponsors from with the Carey community. Participant T-shirts and achievement certificates were provided by Athletics in the Outback.

46

“In planning FLAME, the team sought to identify specific local needs which could be aided through the diverse strengths of local and visiting team members.”

In planning FLAME, the team sought to identify specific local needs which could be aided through the diverse strengths of local and visiting team members. Consequently the FLAME camp offered activities for three groups. A four night residential camp for high school students consisted of athletics, mentoring through art, theatre sports and relationship building. Day camp activities for young adults provided opportunities to develop fundamental coaching skills, practice these skills and engage with their community through art activities. The final group consisted

of primary school students who attended for two days of camp. They participated in athletics games, a mini competition, art activities and theatre sports.

It was an honour to see young indigenous people begin to see their natural athletic ability being realized and worked on throughout the week. It was a privilege to be included in art sessions lead by local leaders to empower young and old alike in sharing their stories and dreaming of the future. And it was humbling to share time, living side by side building deep relationships and to be named a brother during farewell speeches.

Despite running clinics and camps in rural and remote Western Australia over the past 8 years, it always feels fresh and new as relationships deepen and new opportunities open up. Thank you to the community partners for accepting us and allowing us to be a part of your community and journey. And thank you to all the supporters for your support. We look forward to a future of building our already strong partnerships to enhance opportunities for rural, remote and indigenous communities.

ATHLETICS FOR THE OUTBACK

PEAK PERFORMANCE HIGH JUMP

Continuing our analysis of the performance progression of the best athletes of their respective events, we examine the best performances of leading National and Elite athletes in the High Jump

ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

Joseph Baldwin competing in the Under 20s at the 2017 Australian Athletics Championships. (Photo by Mark Metcalfef/Getty Images)

What the Research Says

Hollings, Hopkins & Hume (2014)

The age of peak performance for High Jumpers was found to be 26.1 (± 2.5) for men and 25.6 (±2.5) for women.

Schulz & Curnow (1988)

Based on a study of gold medalists, peak performance of High Jumpers occurs at 23.7 (±4.2) years old for women and 23.1 (±2.8) for men.

Key Facts

Peak Age for Olympic Gold?

The last eight male Olympic Champions have been between the ages of 24 and 29. However...

Late Bloomers

Five of the last six female Olympic Champions have been over the age of 30.

Development Years

The mean improvement from Under 14 to Open Australian National-level High Jumpers was 16% for females and 36% for males.

24 Years Old

The youngest age at which an athlete’s Personal Best has a ‘strong’ correlation wtih their career best performance.

49

PERFORMANCE PROGRESSION OF ELITE JUMPERS

Understanding the career progression of elite High Jump athletes assists coaches to design appropriate and successful long-term athlete development programs that gets athletes performing at the right time.

Figure 2 and Table 2 show the progression of the season's best performances of the top 8 male performers at the 2016 Olympic Games. The results indicate that the top six performers all achieved the best performance of their career between the ages of 23 and 26 (median age= 25). This supports the findings of Schulz and Curnow (1988), who found that the window of peak performance of elite High Jumpers stretched from 21 to 26. However, none of the top 9 performers from the 2016 Olympic Games peaked prior to the age of 22, suggesting that improvement up until 23 years of age is the most likely progression for most athletes.

An Pearson's corelation coefficient test was conducted to assess the relationship between career Personal Best performances and the Personal Bests of the athlete at 19, 22 and 24 years of age. To increase the strength of the analysis, results of all athletes from the 2016 Olympics were considered. The results demonstrate that among elite athletes:

• There was a weak correlation between best performance at 19 years and career personal best (r=0.3762, n=41).

• There was a moderate positive correlation between best performance at 22 years and career personal best (r=0.43, n=44).

• There was a strong positive correlation between best performance at 24 years and career personal best (r=0.69, n=44).

These results suggest that among elites, an athlete's personal best at 19 years of age is a weak indicator of their future performance, meaning a high personal best at 19 is only weakly correlated with high career personal bests. By contrast, an athlete's personal best at 24 is strongly correlated with career best performance, suggesting that it is by 24 that athletes are more likely to be achieving at or near their potential.

This highlights the importance of the athlete's development between 19 and 24 and may be an indicator for coaches to view these years with a long-term outlook for achieving success as an athlete enters their mid-20s.

performances

Athlete/Age 16

Derek Drouin -

Mutaz Essa Barshim -

Bohdan Bondarenko 2.15

Robert Grabarz -

Andriy Protsenko -

Erik Kynard -

Majd Eddin Ghazal -

Kyriakos IoannouDonald Thomas -

50 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

2.1 2.15 2.2 2.25 2.3 2.35 2.4 2.45 16 17 18 Season's Best Performance (m) Derek Drouin Erik Kynard

Figure 2: The season's best

Table 2: The season's best performances

performances of the top nine High Jumpers at the 2016 Olympic Games.

performances of the top nine High Jumpers at the 2016 Olympic Games with Personal Best indicated in green.

PEAK PERFORMANCE Statistics from the IAAF 51 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Years of Age Drouin

Grabarz

17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 2.07 - 2.27 2.26 2.23 2.31 2.38 2.40 .237 2.38 2.28 - 2.14 2.31 2.35 2.39 2.40 2.43 2.41 2.40 2.40 2.26 2.19 2.26 2.15 - 2.3 2.31 2.41 2.42 2.37 2.32 - 2.22 2.14 2.21 2.27 2.22 2.28 2.28 2.37 2.31 2.28 2.33 2.31 2.10 - 2.21 2.30 2.25 2.31 2.31 2.32 2.40 2.32 2.33 2.30 2.15 2.22 2.25 2.31 2.34 2.37 2.37 2.37 2.35 2.30 - - - 2.17 2.20 2.16 2.22 2.28 2.26 2.23 2.26 2.31 2.36 2.32 2.00 2.15 2.28 2.27 2.23 2.35 2.27 2.32 2.30 2.33 2.30 2.28 2.29 2.29 - - - - - 2.23 2.35 2.26 2.30 2.32 2.32 2.27 2.32 2.25 2.34 2.37 2.29

Mutaz Essa Barshim Bohdan Bondarenko Robert

Andriy Protsenko Majededdin Ghazal Kyriakos Ioannou Donald Thomas

As with our analysis of elite sprinters and throwers, we are again provided with evidence of late developers who realise the best performances of their career in their late 20s or even into their early 30s. However, it should be noted that both Ghazal and Thomas, who have a PB at 29 and 32 years respectively, commenced their international careers at a later age. This reinforces the importance of considering the training age of an athlete when examining the age of peak performance.

Athletes who begin specialized training for a single sport have been shown to achieve their peak performance at an earlier age than those who do not (Smith, 2004). This may explain why Thomas, who was originally a basketballer and only began high jumping at 21 years of age has been able to achieve his best performance at 32 years of age.

The delay in the best performances of latecomers to the sport may be explained by the need for more time being required to hone their technique and to develop the competition skills required to perform at IAAF sanctioned events.

Coaches should take this information into account when setting objectives for high jumpers who come into the sport later and prepare their athlete for competition into their late 20s and early 30s. However, for athletes who have been in the sport since their teenage years, it would appear that they are most likely to hit their peak performance between the ages of 23 and 26, and male athletes have the greatest chance of Olympic success during this period.

52 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

Your chance to connect with the experts of their field

ASK THE EXPERTS WITH MIKE HURST

In the previous edition of Athletics Coach, leading Australian Coach Mike Hurst and his team of leading Australian athletes kindly offered their time to coaches to help answer any questions that you had regarding coaching the 400m

Q: Dear Mike,

I have just started coaching a 15-year-old girl, who has been running the 300m hurdles at Little Athletics. She is moving up to shield club level in Melbourne this Track season, where they run the hurdles over 400m.

She is a strong runner and has been running since she was 10 years of age, she also runs the 800m. My question is how many times she should run over the 400 hurdles in a season?

It's great to be able to chat with a coach with your knowledge.

Mark Carey

Response provided by Mike Hurst and Jana Pittman

Jana Pittman: We always said 12 max runs over 400 at peak racing. Expecting 6-8 to be good the others pre season or post season - but if it's her first I would half that number don't you think? Although she might just need practice and those little legs recover quicker than older ones. The big thing is making sure she runs 400s too for the speed, as often they don't run 'hard' enough due to some inefficiency over the hurdles.

Mike Hurst: Yes I do agree, although if anything I'd like them to develop Speed Reserve time by hitting the 200s.

Jana Pittmann: Yep that's perfect, that's what I did so I would run the 400 one week and the 200 the follow week - sometimes with the hurdles. Even some sprint hurdles to get fast hurdle practice.

***

54 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

55

Q: Dear Mike,

I have heard that in other countries athletes are not encouraged or even stopped to run the 400m before they turn 18. Is this something that you agree with? Should I be discouraging my High School runners from competing in the 400m?

Thank you so much I’m very excited to hear your response.

Michael Lee

Response provided by Mike Hurst, Jana Pittman and Marree Holland

Jana Pittman: That's a trick question and I think it's really dependent on the kid. I didn't run 400s until 14/15 years of age and I do agree before that they are brutal but a kid needs to learn to run out of their comfort zone and I personally think by 16 it's ok. Especially when you see some of the top kids in the world running incredibly by 19!!

Mike Hurst: People who have a big aerobic base due to training like a middle distance runner will usually dominate the junior women's 400 but future success lies with those who can develop their speed and subsequently speed-endurance or, as I prefer to describe it, "endurance at speed". What speed? Well it has to be Race Pace. So I would work toward the 150 to 340m zone and eventually allow the athlete to take a crack at the entire 400m distance.

Maree Holland: Naturally everyone is entitled to their own opinion but I don't agree with Michael's statement...Based on my experience I believe my school competitions gave me the necessary background physically and mentally to develop into an international competitor. As you would know I ran 53.8 as a 16 year old and went on years later to run 50.24 at the age of 25. What damage did it

Maree for generously sharing their time and expertise with the wider athletics community.

Next Time...

Commonwealth Gold Medalist and National Junior Throws Coach, Scott Martin joins us on 'Ask the Experts' to answer your questions.

Do you have any technical questions about coaching the throws events?

Do you want to know more about the training program that took him to Gold?

Send in your questions via email

***

56 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

57 ASK THE EXPERTS

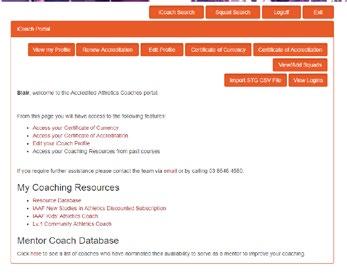

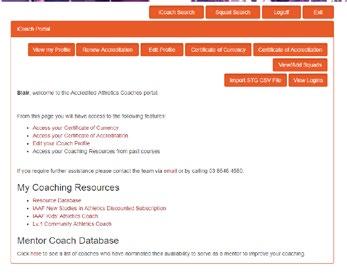

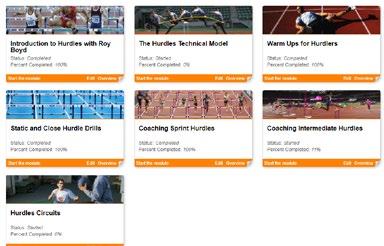

MY COACHING RESOURCES

Throughout 2017, we have continued to expand the database of available content online for your access at any time and we plan to continue adding new resources to support your ongoing education throughout 2018.

Resources recently added online include:

Resource Requirements Description

Run, Jump, ThrowSkills, Drills and Games Interactive Resource

1 Community Athletics Coach - Revision Videos

STAR Interactive Resource

Hurdles with Roy Boyd Course

Enrolled in a Level 1 Community Athletics Coach course.

Enrolled in a Level 1 Community Athletics Coach course.

Enrolled in a Level 2 Intermediate Club Coach Course

Enrolled in a Level 2 Intermediate Recreational Running Coach course

Enrolled in a Level 2 Advanced Coach - SRH course

This interactive video series examines the skill compenents and coaching tips for the fundamental movement patterns of coaching running, jumping and throwing.

This online course takes coaches through the material that is covered in the Level 1 Community Athletics Coach course.

This series of videos gives a detailed analysis of the technical model of the track and field events (excluding Hammer and Pole Vault). Includes suggested drills, sessions and training programs.

This manual provides a review and extension of the course content of the Level 2 IRR course. Offering a combination of evidence-based findings and expert opinion, this guide is designed to challenge your practises and prepare yourself to take the next step in your coaching of recreational runners.

This course offers a thorough guide to coaching hurdles through the lens of coaching legend Roy Boyd.

Level

Level 2 Intermediate Recreational Running Coach Revision Manual

From STAR Interactive Resource

58 ATHLETICS COACH - JANUARY 2018

From Run, Jump, Throw - Skills, Drills and Games Resource

ONLINE

RESOURCES

ONLINE

Where do I find the Course Resource Pages?

How to Access

Enrol for this course through your Course Resource Page

Enrol for this course through your Course Resource Page

Enrol for this video series through your Course Resource Page

Download the manual from your Course Resource Page

Enrol in this course through your Course Resource Page

You are able to access your Course Resource Pages for any course that you have successfully completed by visiting the Coach Portal and clicking on 'Access my Coaching Resources'. Once logged in, scroll down to the 'My Coaching Resources' tab where you are able to see a list of links to the Course Resource Pages available to you. There is also a link to the general Resource Database and discounted subscription form to New Studies in Athletics.