5 minute read

Final part of ‘Into The Peatlands

disinfectant – it sounds weird that these could be good favours in a drink, but they are – peaty, smoky, delicious! And after my dram is drunk, nosing the glass: it smells like a miniature peat fre has been burning in there. The contrast between the delicate smell of the moor and the strong reek from the peats in the whisky is like the difference between ingredients when baking: the four, eggs, sugar and butter are almost odourless, but the aroma of the baked cake is delicious.

The making and selling of whisky is a modern, international, multi-billion-pound business that generates huge revenues for the companies producing it and for the governments that tax it. Its roots are as a ‘cottage’ industry produced domestically on a small scale, and whilst the remnants of the culture that produced it still survive, would it be naive to presume that it doesn’t still exist in that form? The moors are big, dotted with semi-habited shielings and hidden places. Does that curl of smoke signify that someone is drying his socks by the fre, or making a cup of strong, black tea . . . or brewing something stronger?

Advertisement

The novelist Neil Gunn was a lover of whisky. In The Silver Bough he describes an illicit, moorland drinking den inside a remote wheelhouse (an underground Iron Age storehouse) and in his classic 1935 Whisky and Scotland recounts visiting a friend from Caithness who produced a homemade bottle containing whisky that had passed down through his family and was 104 years old. Intrigued by the chance to savour a true Highland throwback made before industrialisation and marketing men dictated taste, they open the centurion bottle:

Let it be said at once that the liquor in that bottle was matured to an incredible smoothness. I have never tasted anything quite like it in that respect. In these old days, when it was the custom to have a fre in the middle of the foor with a hole in the roof for the chimney, some specks of the old glistening soot from the rafters had fallen amongst the malt. Perhaps during the frst few years of maturation this might hardly have been detected – or, again, may have been deliberately aimed at as an elusive part of the whole favour! – but certainly in this extreme age it was all-pervasive; it had become, indeed, the spirit’s very breath.

Peat has that retentive quality. In the digging of it out of the moor you see its timeline stretching back over thousands of years, from fresh buds sprouting on the living turf through the older vegetation down into the roots; the gradation of tone and colour from ochres to umber to chocolate and rich black-brown marking the passing of centuries and millennia of sphagnum – tiny individual lives making up a huge community compressed by time.

In burning this and releasing the peat’s aroma there is an immediate sensory connection with the past. Memories of people and times, of generations now gone, are conjured up. For those still living on the peatlands, there is a two-fold element of honouring those who have come before.

First, there is a physical connection in cutting on the family peat banks, which not only your parents and grandparents cut but which were shared in an annual ritual by your wider community. Whether your family had had that croft since a land-raid post-First World War or since your people had been cleared off ancestral lands to make way for sheep in the nineteenth century, or it had been in the family since way back, there is a ritual there in performing the same actions with the same tools – cutting, catching, throwing – that is almost meditative on this open expanse of moor under huge skies, under the eyes of your god.

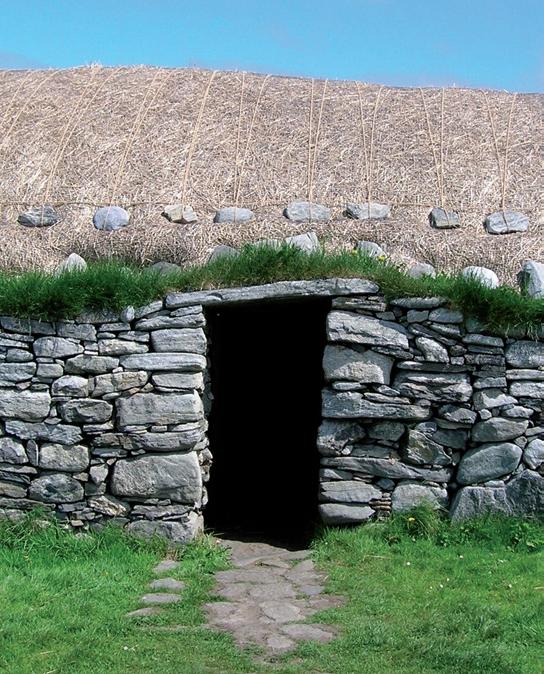

On entering a blackhouse, you are enveloped by the ‘peat reek’. The soot from the peat fres could also fnd its way into the whisky, adding further favour.

Second, there is the burning. By doing this you are not only releasing the smell of your childhood, of people’s houses that you knew, of your own memories, but also the memories of everyone who grew up in your community and those who have always lived in your community. The slightly disinfectant tang holds an almost curative quality; there is a sense of cleansing and renewal.

As the smoke escapes through the chimney, the private becomes public and, walking past, you smell the reassuring and wonderful mix of peat smoke and salty Atlantic air that is as rich as a glass of Bowmore Islay whisky. No matter what time of year, many home fres are kept burning, just as in the past. You also connect in a domestic way to the wider Gàilteachd and similar communities who share your culture and belief systems.

Tha a smuid fhein an ceann gach foid, ‘S a dhorainn ceangailte rig ach neach. Every peat has its own smoke, And every person has his own sorrow.

In days where the fog is down and the ghostly sweeping beam of the Butt of Lewis lighthouse highlights the nothingness and its foghorn boom reverberates like a footstep on the quagmire moor, the smoke hangs heavy, close. But on a clear day with a brisk wind you fancy that the peat smoke can reach all the way to America, twitching the genetic Scots noses of emigrant communities in Nova Scotia, South Carolina and into the West and beyond.