BY AMANDA BENNETT

We are once again delighted to share some of our happenings and updates with you from the Fuqua Orchid Center. As I round into my 22nd year with the Atlanta Botanical Garden and sixth year as Vice President of Horticulture and Living Collections, I can say without a doubt that there is nothing static, boring or unexciting about our orchid collections, facility or future.

Any of us with conservatories know that mechanics are a big deal. The Garden has been investing significantly in repairing and updating systems and mechanics on our twenty-one year old Fuqua Orchid Center. You’ll hear more about that in Becky’s article, but it’s one of those behind-the-scenes things that isn’t as glamorous as the plants but is indispensable for growing them. The facilities that support our work is a basic necessity that can be taken for granted if not property maintained. We are looking forward to another twenty plus years of reliability and stoic care our facilities provide.

As for collections, and like many gardens, we are working on prioritizations, succession planning, disaster preparedness, inventorying, and execution of collection management plans. We are thinking of more projects concerning our orchid collections than we have time or capacity, but we all know work with plants is never done. With a talented team, incredible collections and displays and clear view of the next twenty years, we are thankful for the opportunity to continue collaborating and sharing with friends and colleagues like you.

Amanda Bennett Vice President, Horticulture & Collections

Atlanta Botanical Garden

We are very fortunate that the Garden has invested in substantial upgrades to greenhouse facilities, starting in 2019 with the greenhouse control system and continuing to include the greenhouse mechanical systems.

Every greenhouse manager is well aware how critically important fully functional cooling systems are now. Over the last two winters we replaced our 20-year-old Acme wet walls with new Munter’s systems. The new recirculating 60 gallon water reservoir is wall mounted and much more compact than the 200 gallon subterranean reservoirs that they replaced. With the new system, we have noticed a significant drop in temperature and were especially grateful for it this past summer, as temperatures outdoors reached 95º every day since June.

Our Tropical High Elevation House, with its air washer cooling system and high pressure fog, provides a unique experience for our visitors – a chilly, buoyant atmosphere with moss-laden rocks and trees studded with Dracula, Porroglossum, and Trisetella, all overlaid with a stratum of cool mist. Since 2019, we have replaced three of the four major components of the air washer system: the chiller, cooling tower and Big Fan. The engineers at Bahnson have replaced the iconic 10’ x 10’ Big Fan with a wall mounted array of nine smaller fans and the effect in the High Elevation House is striking. On start up, the old Big Fan sounded a bit like the StarShip Enterprise (the 1960’s TV version) reaching warp nine. By contrast, the sound of the new fan array is barely discernible, even in the High Elevation House. It is far more energy efficient as well. We are thrilled about these upgrades. Replacement of these essential systems will allow future generations to continue to enjoy the Tropical High Elevation House for years to come.

BY BECKY BRINKMAN, Fuqua Orchid Center Manager

We have lots of exciting projects underway. We continue to move forward with new plantings, new facilities upgrades and most importantly, succession and preservation of our high priority orchid accessions. In addition, we’ve initiated two projects that I’m tremendously enthusiastic about. Over the last two years, Taylor Marshall, Orchid Horticultural Curator, has taken our initial efforts at biocontrol in the Orchid Center from the fledgling stage to a fully realized biocontrol program. More about that in his article below. Another exciting project is the 3D mapping of orchid accessions in our epiphyte trees. Shakim Cooper, our newest Orchid Horticultural Curator, describes this innovative project in his article on pages 12-15

We are pleased to welcome Shakim Cooper as our third Horticultural Curator, joining Sarah Carter and Taylor Marshall. He joins us from the Outdoor Horticulture team. Shakim has a dual background in horticulture and engineering and he is a talented sculptor with a good eye for three-dimensional representations. This extraordinary skill set has allowed us for the first time to pursue a once distant dream of 3D mapping the orchid accessions in the FOC epiphyte trees. Read the article on pages 12-15.

You may know that the Garden's Scott McMahan, Manager of International Plant Exploration, has been making numerous collecting trips across Southeast Asia through the Garden's International Plant Exploration Program, or IPEP.

This year the Orchid Center has been able to capitalize on the rich returns from Scott’s travels to Vietnam and China by creating new installations for IPEP plants in our display greenhouses. In the Orchid Display House, Sarah Carter has been hard at work expanding the Vietnam/China bed to include non-hardy IPEP plants. After a week of hauling and installing limestone boulders and soil, Sarah planted 25 new Paphiopedilum from our collection, along with the very rare Magnolia guandongensis and Amentotaxus natuyensis from the IPEP program. This renovation doubles the size of our Vietnam/China bed and brings the total number of Paphs permanently installed in the Orchid Display House to 63.

In the Tropical High Elevation House, we’ve removed one of our older epiphyte trees in order to make room for a new Vietnam/China bed that hosts orchids and other plants collected by Scott at higher elevations, including Arisaema pingbianense, Raphiocarpus jinpingensis, Polygonatum zhejiangensis, a gorgeous unnamed Podophyllum species, Hedychium yunnanense and nine new Cymbidium plants from various sources including Cymbidium elegans and C. wadae. Also in the High Elevation House, we are staging in replacement of the shrub layer that supports our Nepenthes in our Mt. Kinabalu bed.

Some of our shrubs, mainly the Rhododendron laetum, have proved just too enticing to Heliothrips and powdery mildew. The nine new Vireya Rhododendrons received from the Rhododendron Species

Stanhopea seedlings

Foundation are being site-tested for resistance to both. They include R. renischiana, phaeochitum, stevensianum, ruschforthii, kawakamii, alborugosa, with good results so far. The next phase of renovation will include adding new highland Nepenthes and removing some of the older stems on established plants to make room for new basal shoots.

The cornerstones of our five year Orchid Collection Development Plan are succession & preservation. The goal of succession is to maintain the vigor of the collection through ongoing planned replacement of old or ailing plants with plants produced in our lab. Preservation is accomplished through seedbanking. To initiate those processes, we have established criteria for high priority status for our orchid accessions (i.e., wild provenance, IUCN red listed, undescribed species, holotype, active research), identified our high priority accessions for our core orchid collections, and have marked those plants. Since 2022, we have sent 27 high priority capsules to the mircropropagation lab and seedbank. The seedlings we produce are used for succession, installation in the Fuqua Orchid Center and distribution to other botanical gardens and universities.

We are grateful for some very generous donations over the last two years. Our orchid collection has been enriched with donations that have made possible the purchase of flasked orchids for our

Madagascan species collection, for our Euglossine bee pollinated Lycastinae collection, and for installation on our newly rebuilt cork trees in the Orchid Display House and High Elevation House. In addition, we have been able to purchase three excellent microscopes: compound, dissecting and field scopes, to assist with insect identification, floral identification, pollination and photography.

1. We are very pleased to add Ida jimenezii, a rare Colombian species to our Ida collection in the High Elevation House. It’s one of the larger species with four inch ivory flowers tinged with green.

2. Plants of the World Online describes Dichaea ancoraelabia as a subshrub, though it is herbaceous and appears to max out at about five feet tall I find all Dichaea irresistible, but this one is especially appealing on account of its unusual growth habit. Unlike many Dichaea species, it is fairly robust and doesn’t break apart on handling.

3. Fans of visual chaos will appreciate the spots-onstripes aesthetic of Catasetum denticulatums' flowers. C. denticulatum is a hot-growing Brazilian species thriving in our Vanda greenhouse.

4. We received Jumellea teretifolia from Louisiana Orchid Connection. I jumped at the chance to get teretifolium on the strength of the name alone. Who could resist a terete-leaved Jumellea? This Madagascan species may end up in our High Elevation House as it grows at 1,300 to 2,000 meters elevation.

5. A relatively newly described (2016) Philippine species, Vanda mariae, is a very handsome smaller Vanda. The brilliant red flowers are yellow on the reverse side.

6. As the name suggests, Chiloschista pusilla species is tiny, even for a Chiloschista, and the tiny roots make the yellow flowers look enormous. Leafless orchids are not hard to grow, once you find the substrate that works for them in your greenhouse. Ours have rejected all forms of wood in favor of good old fashioned plastic. We lay them, sans medium, on the bottom of a net pot with the sides cut away.

7. Ida reichenbachii species has lovely olive colored sepals and an ochre colored lip. Ida are stunning plants, and our Ida collection is now large enough to merit its own dedicated space in the High Elevation House.

8. Angraecum ankeranense is long stemmed multibranched smallish Angraecum with a 3” flower and a strikingly long spur. It is a Madagascar endemic, listed as Threatened by the IUCN.

BY SARAH CARTER, Orchid Horticultural Curator

Coelogyne (Dendrochilum) wenzelii settling in to its new home

When you have a collection of epiphytic orchids to show off, you need some way to get them up in the air where they like to grow. In the Orchid Center, we have a couple of ways we grow and display our epiphytes in our permanently-planted, public display areas. Made of natural materials, these structures have lasted a remarkable amount of time given constant high humidity and daily watering, but over the last several years we have needed to replace and replant them one-by-one.

One way we go vertical is with our “epiphyte trees”. These are donated Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana) trees that we cut, clean and trim, and stand up in the beds. We use steel cable to secure the trees to the beams in the ceiling of the greenhouse.Red cedars work well for us because they are abundant,

rot-resistant, and have a surface that orchid roots will grow onto. Once the tree is in place, we begin attaching the orchids. Most of the time we use monofilament to tie the orchid directly onto a branch of the tree. For orchids that like more moisture, we will tie them on with a little bit of moss around their roots. We use either live moss harvested from other areas of the Orchid Center, or a few strands of long-fiber sphagnum moss. This also helps protect the new young roots from being damaged by the monofilament. However, we have to be careful not to use too much moss because it will cause root rot if too much moisture is retained. If the plant is already well established on a mount of cork or tree fern, we will use decking screws to attach it, mount and all, to the tree.

As with any planting, it is important to put some thought into plant selection and placement. It is best to choose small plants that are showing new root growth. Small plants are easier to secure tightly to the branches. If the orchid is too loose or does not have actively growing new roots, it will have difficulty anchoring itself to the branch. When choosing what plant to put where on the tree, we keep in mind which direction the light is mostly coming from, and that the upper branches of our epiphyte trees are generally brighter, drier, and hotter than the lower branches. We also avoid placing the orchids on the underside or in the fork of a branch. We have found that they have difficulty drying out between waterings in those spots.

Another way we “plant” our epiphytes and make use of our vertical space is to attach them to cork bark that surrounds metal structural posts in our display greenhouses. Cladding the posts in cork bark is quite an undertaking, but like the red cedar epiphyte trees, the cork is rot-resistant and takes many years to begin deteriorating. Cork also has a surface texture that orchids just

love to get their roots into.

To make our cork posts, we begin with tubular cork, hollow cylinder-shaped sections of the outer bark of the Cork Oak (Quercus suber). If there is not already a split along its length from harvesting, we use a saw to make one. Then, we are able to slip it around the post like a jacket. We tighten cable ties around it to keep it securely in place and make sure any plants below the post are protected with plastic or cloth for the next step.

Using insulating foam sealant (such as Great Stuff), we fill the inside of the tube so that

Newly installed Cattleya maxima seedlings on a cork post

A happy new shoot of Bulbophyllum cumingii growing on red cedar

once the foam is expanded and cured there is no space between the post and the cork. This not only keeps water from collecting inside the cork tube, but also adheres the tube to the post. The foam cures overnight and then it’s time to remove any excess foam and cut away the cable ties. To make the posts look more natural and to seal and cover the seams between sections, we use a combination of clear silicone caulk and tree fern fiber.

As with our epiphyte trees, we choose and place orchids according to their size, growth stage, and environmental requirements, and the conditions along each section of the post. We attach orchids with monofilament, using a few decking screws placed around the root mass as anchor points for the monofilament. Or, in some cases, we establish seedlings on their own small, flat pieces of cork and then attach the cork slab to the new post.

And of course, whether we are planting an epiphyte tree or a cork post, aesthetics are a consideration. Orchids with miniature flowers are placed lower where they can be more easily seen by our visitors. We choose orchids with different flowering times so that there is always something in flower. Sometimes we install several plants of one species all together so that their flowers emerge in one big impressive mass. In other cases, we plant a large variety of species in one tree to show off the incredible diversity of colors, textures, and forms found in the orchid family.

Our visitors might be focused on the flowers they see on our new epiphyte trees, but what we love to see most is all those fresh new roots growing onto the branches or cork. It means our orchids will flourish there in their new home and that our new epiphyte trees and cork posts will be enjoyed for many years to come.

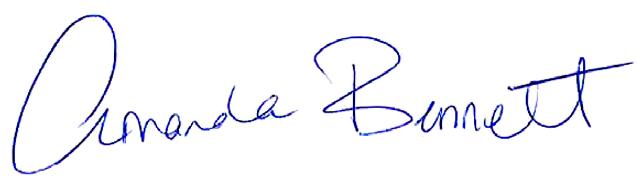

BY SHAKIM COOPER, Orchid Horticulture Curator

Two-dimensional mapping is by no means revolutionary when referring to horticulture or in general. As a garden space, it is of utmost importance that the location of each and every specimen be known. Whether this be for standard horticulture, inventory and/or anything else in between the whereabouts of plants is a necessity. Despite this necessity, the mapping process is often done by hand where exact measurements are not mandatory most of the time. There is also substantially less detail that goes into a two-dimensional map as often they are derived from preexisting floor plans of the same dimensions. Unfortunately, there are certain areas within the Garden that require a different approach.

In most cases, the aforementioned approach is sufficient for outdoor spaces and areas only having terrestrial specimens. The Fuqua Orchid Center however, has specimens that grow both terrestrially and epiphytically. This presents a unique viewing experience to guests both new and old, where plants can be enjoyed in either a manicured or naturalistic style. Focusing on the more naturalistic displays, epiphytic specimens can be seen mounted on just about any vertical space available. Whether it be living trees, dead trees or handmade cork structures, the only limit for orchid mounting is the ceiling.

Enter the current dilemma of the Fuqua Orchid Center: mapping the myriad epiphytic specimens effectively for record keeping. A single plant would require multiple detailed views all relative to its location within the Fuqua Orchid Center without interfering with its neighboring plant. On a scale as massive as the FOC even with the most artistically inclined involved this would be a daunting, if not impossible task.

Generally speaking, modeling organic objects in a software intended for inorganic objects would prove difficult. To circumvent such difficulties, reducing each feature to simple three-dimensional shapes allows for accurate mapping while remaining recognizable. Like any object, the mount/tree needs to start in a 2D sketch then systematically built into a 3D object. This is done through the mount /tree being reduced to simple geometry that is replicable via Onshape’s features. Depending on the feature, this may look like a simple wire frame or more complex polygon in which a mesh is then generated around.

The actual grow space is modeled in a similar fashion. Using the preexisting floor plans for consistent scale, numerous frames and polygons will be the basis for a 3D version of the current display space. Despite the plants being the sole purpose of this mapping, they will actually not be modeled. Instead, each plant will be reduced to a point that can be pinned to the respective mount/ tree along with the necessary labeling for identification. Visual clutter is greatly reduced this way and allows for plants to be placed as accurately as possible.

With the numerous software options available there is no shortage of ways to 3D modeling objects. The largest deciding factors were versatility and familiarity. Ideally a brand with high versatility that is familiar enough to reduce the time necessary

for training would allow the maximum amount of working time. Despite the project being spearheaded by such a small team, eventually there will be other parties involved in need of training. Having a familiarity aids in educating the next generation of persons that will be involved in this project.

Machine capabilities and data management were also of great consideration. Not only would cloud based storage allow for potentially unlimited space, but much easier transferral of documents between users/devices. This too would reduce the possibility of outdated model files being mixed in with newer versions.

From a technical standpoint, the workload between each machine needs to be minimal enough that extremely pricey equipment is not required, yet powerful enough to model all the assets present without too much delay. There is also the matter of program familiarity, as these programs can be daunting to persons totally new to 3D modeling and software of that nature. It is also worth mentioning that the style of the software is heavily influenced by the audience it is intended for, meaning that certain features are available or improved depending on the software and its user. Case in point, one of the software candidates known as Blender is geared more towards artists and animators, so while it is able to generate high amounts of detail, it lacks the ability to produce technical drawings. Google SketchUp was another candidate that is actually more intended for architecture and potentially mapping but was hindered due to its technical requirements. Ultimately choosing Onshape for this project allows for filtering of information, as well as a highly detailed breakdown of features for modeling and mapping.

Before any modeling can be done measurements must be taken. Not only will measurements of the mounts and trees be required, but so will their positioning relative to the spaces they exist in. For large measurements, a standard tape measure is more than sufficient. In order to achieve as accurate as possible measurements on smaller features, digital tools such as calipers, angle ruler and range finder are needed.

There are a few challenges one can expect with such a project. It goes without saying that such a project will take quite some time, but the bigger matter is making progress while the public spaces are open for viewing. Due to the unfortunate fact that any of the persons involved are opaque, there are multiple instances where numerous specimens are obstructed in order to gather measurements. Currently, stationing the laptop and other instruments out of the walkways and traveling to the target mounts/ trees reduces traffic along pathways. The other large hurdle with time is of course management of the resource so that horticulture does not fall to the wayside. Groundbreaking as it may be, the plants have to remain in the utmost care so that there is anything left to map by completion.

As one might expect, the location itself is not necessarily conducive to the project at hand. Between frequent misting from the overhead system and any other mystery drips, only a finite amount of

time can be spent in the High Elevation House with electronics. Attempting to measure features well out of reach also presents its own challenges. Certain areas require heavy machinery, and in other cases, may be physically impossible to reach and will require well founded estimations. Naturally, all the precautionary measures regarding this mapping must be put into consideration to ensure maximum safety and efficiency.

Not only can 3D modeling revamp the way the Garden maps plants throughout the garden, but it also serves as another tool capable of integrating with and revitalizing the current systems in place. The future of mapping in the Fuqua Orchid Center looks bright and three-dimensional as this project continues through 2025.

AUTO-GENERATED 2D DIAGRAM OF FIGURE BRANCH FOR ADDITIONAL MAPPING

1:1 SCALE 3D MODEL OF THE FUQUA ORCHID CENTER. THIS MODEL WILL HOUSE ALL OF THE EPIPHYTE TREES AND MOUNTS.

BY BECKY BRINKMAN, Fuqua Orchid Center Manager

Among the lesser known genera of Euglossine bee pollinated orchids that we grow in hanging baskets, Acineta and Lycomormium are two of the most rewarding. In an intermediate greenhouse, they grow robustly and produce a vigorous root system. The large waxy flowers, produced on pendant grapelike racemes, never fail to stop me in my tracks for a closer look. Both produce simple gullet flowers in which the sepals, petals and lateral lobes of the lip create a short tunnel around the column that guides the bee toward the fragrance at the center. Upon backing out, the bee brushes against the overhanging column and picks up the viscidium of the pollinarium on its back. As members of sister subtribes Stanhopeinae and Coeliopsidinae, Acineta and Lycomormium have cultural requirements that are fairly similar.

We grow our plants in a 60º night minimum greenhouse under 60% shade. The wooden slatted baskets of both genera are organized in rows directly in front of the wet wall, and are therefore on the cooler side of the greenhouse. Acineta likes to be slightly brighter, drier and cooler than the Lycomormium. We grow two species in the Tropical High Elevation House: Antioqiae and Cryptodonta. The Lycomormiums make tremendous specimen plants reaching three inches from base to tip. Their leaves are thin, like those of Peristeria and Coeliopsis, and so one has to be careful not to hang the baskets too high in the greenhouse, or the leaf tips will scorch.

Our preferred mix for many years for the Stanhopeinae and friends has been a 50-50 mixture of premium long fibered sphagnum and coarse chopped tree fern fiber. Our Acineta and Lycomormium were last repotted during the pandemic lockdown and the mix is still in good condition. Fertilizer is 150 ppm Cal Mag twice a month, weather permitting (we often skip fertilizing during extended periods of rain or heavy cloud cover or short days). Both genera are attractive to boisduval scale, which we keep at bay with alternating spray applications of Talus and horticultural oil in the spring. This year I’ve noticed Echinothrips on the buds and flowers of both genera. For Echinothrips, we now apply predatory mite (Amblyseius swirskii) sachets proactively and throughout the year on all susceptible orchid inflorescences. The predatory mites only consume immature thrips, not the adults. Fortunately, Echinothrips are not known to transmit plant viruses.

Of all our Euglossine bee pollinated orchids, Lycomormium is the biggest pain to pollinate. As with Gongora, the pollinia need to desiccate for a good hour or more before they can be made to slide inside the absurdly narrow stigmatic slot. The pollinia are relatively enormous and without desiccation the whole frustrating business can take 20 minutes of intense concentration and leave the human pollinator sweaty and exhausted. My admiration for Euglossine bees always rises a few notches after pollinating a Lycomormium. My usual routine is to extract the pollinarium early in the day, slap it onto one of the sepals, and return in the afternoon to pry the viscidium loose and complete the pollination.

BY TAYLOR MARSHALL, Orchid Horticultural Curator

In the perennial pursuit of more effective and sustainable pest control, the Fuqua Orchid Center (FOC) has made some serious shifts to our usual routine over the last two years. After grappling with viral vectors, persistent pests in the difficult-to-access canopy, and a relentless species of wax scale; we knew it was time for change. In early 2022, the team undertook a pilot Integrated Pest Management (IPM) program beginning with a study of the pest species of the FOC and their related natural enemies. After identifying numerous species of thrips and aphids, mealybug and scale, as well as a few isolated populations of predators and parasitoids; it became clear that the way forward was not chemical, but biological.

The first step was to scale back broad-spectrum insecticide usage, arguably the most common refrain of IPM proponents. This allowed us to inoculate the greenhouses with beneficial insects and mites as well as paved the way to recruit endemic and naturalized enemies of our pests. The most immediate and, frankly, dramatic impact here was in our thrips-afflicted Catasetinae collection, which went from a 6-month rotation of insecticides with weekly applications to nothing more than entomopathogenic nematodes and predatory mites every six weeks. Even under the intensive pesticide regimen, the thrips were still causing enough damage that the future of that Catasetinae collection was in question. It is important to note that thrips are one of the most insidious pests affecting our industry globally. Their cryptic behavior, ease and speed of reproduction, plus their tendency to rapidly develop pesticide resistance make them one of the world’s most economically important pests. Yet in the first year of shifting to biocontrols, thrips populations were reduced below a threshold the Orchid Center had not achieved in 10 years. In its second year, the continued usage of mites and nematodes has allowed for the truly remarkable resurgence of our Catasetinae and has managed other species of thrips across our collections.

One of the biggest challenges we’ve faced in the development of a nuanced IPM program on a modest budget has been precision. As we demonstrate success, we still aim to be as judicious with our beneficial releases as possible. This requires two equally important assessments: knowing specifically which pests we are dealing with and prioritizing the most important pests among our collections.

As the horticulturist charged with identifying the FOC’s pests and coming up with a strategy to control them, I had to first brush up on the necessary anatomy and identification features. Then we needed a few pieces of equipment as well as some collection and preparation supplies. Instrumentally we were able to purchase two, quality microscopes- one dissecting and one compound light. The species-level diagnostic features for most greenhouse pests require some fine manipulation to reveal and are only visible at 100-400x magnification. So, without the proper tools, it is difficult to be completely confident in your identification. In addition to microscopes, I needed the supplies to collect, preserve, prepare, and mount specimens for identification. These include 95% ethyl alcohol, potassium hydroxide, and a number of other chemicals that

Slow-release sachet containing the predatory mite, Amblyseius swirskii, hanging on the peduncle of a Cattleya sp. flower.

require proper storage. Conveniently, our greenhouse manager was beefing up our chemical storage facilities at the time and we were able to store everything properly. I should note that each group of insects and arthropods have slightly different mounting protocols in the literature, but that some can take several hours to complete. Thankfully, the Garden has seen the value in spending resources and time to allow for the proper identification of our pests which enables us to best plan for their control.

A tidy example of how knowing the exact species has helped us achieve control of a pest would be Chaetanaphothrips orchidii on our Sobralia rosea. This thrip is a small one, often less than 1mm in length. It likes to hide in the creases of leaves, under bracts, junctions of stems, etc. This makes it difficult to reach with conventional spraying and would require a large volume of pesticide that would end up drenching anything below it and soaking into the ground. Upon inspection of a large (~10ft.) S. rosea, with global damage characteristic of either mites or thrips, I found this small pest as well as something unexpected. Crawling amongst the adult C. orchidii and their offspring was a small parasitic wasp with fringed wings. While identification of parasitoids is extremely difficult due to their miniscule size and consequent lack of study, the fringed wings are a hallmark of the superfamily Chalcidoidea, an economically important group of parasitoids. As the thrips fed around them, ignored, it became clear that these wasps were searching for something specific. They weren’t seeking larvae in which to oviposit, however; they were inserting their eggs directly into the cuticle of the leaf. This Chalcid is an egg parasitoid, pinpointing where female thrips had laid their eggs into the leaf and following suit so their own larvae could develop and feed in the same shelter that so many thrips leverage (to our collective dismay). Indeed, this was confirmed by the presence of exit holes in tiny galls formed by the developing parasitoids as they fed on the thrips eggs. While this was an exciting story to uncover, we still needed to assess its control effectiveness. We observed the plant for several months of new growth with the only intervention being the continued use of predatory mite sachets (A. swirskii), allowing the parasitoid to do its work unimpeded. However, after a period of time passed, the new leaves on the S. rosea were suffering the same level of damage and no shift in insect populations was noticeable. Therefore, we decided to use a wettable powder formulation of Beauveria bassiana, the fungal pathogen of insects well known as a control of many important species of thrips. Despite the potential to harm the beneficials we had found, ultimately control and display-worthiness are our goals and this complex of pest, parasitoid, and predator was insufficient to reduce the pest population to acceptable levels. We applied several treatments with an Ultra Low-Volume Cold Fogger to only the affected plant material, hopefully sparing surrounding populations of beneficials. The fine particle size of the Cold Fogger (~30µm) allowed for better contact with the pests in their nooks and crannies and the low volume resulted in no polluting runoff.

Another helpful discovery informing good IPM decisions is the case of our Barnacle Scale, Ceroplastes cirripediformis. This soft, wax scale has become a real thorn in the FOC’s side in the last few years. Presumably imported on some new plants from Florida, where it is naturalized, it has proven itself quite the resilient polyphage. Working its way high into the canopy, it evaded early attempts

at control by ground-bound sprayers. Since beginning our IPM program, we have had difficulty finding a commercially available biocontrol to address the growing problem. The only way to stymie their advance has been physical removal- sometimes of entire groups of plants from our spaces. We had many specimens of Crescentia installed with the hopes of using them as living epiphyte trees to display our miniature orchids in the Orchid Display House of the FOC. Unfortunately, they proved such a magnet for C. cirripediformis that they were removed, one by one. We have been using a chemical control, Talus 70DF, that is reportedly very specific to scale and mealybug. The active ingredient, buprofezin, is an insect growth regulator that inhibits chitin biosynthesis. However, it requires application during their vulnerable crawler stage and can only be applied once per season, which for us, is essentially once per year. Our populations of scale go through multiple generations a year and they are not all synced with each other, so targeting that brief window of vulnerability has proven difficult. The one very attractive observation we’ve made is that it does not completely wipe out beneficials like parasitoid wasps. This, at least, is encouraging enough to continue its integration into our IPM program. So, while puzzling over a Pseuderanthemum carruthersii this winter, I noticed a large number of second instar juveniles still on the leaves while the rest of the scale population on that plant had progressed to the overwintering mature stage on the stems of the plant. When I looked more closely under the microscope, I noticed exit holes in some older second instars as well as intact mummies (host insect with developing wasp larvae inside). As this was a parasitoid that required a particular early stage of its host, it became clear that the parasitoids, too, were overwintering. Generally we take the winter break from insect reproduction cycles to physically clean the plants of any living pests we can find, as well as the remains of dead ones so that we can better assess when pest numbers begin to increase. In this case, however, that would have wiped out a new-to-us biocontrol that has the potential to finally bring our barnacle scale problem under control. To that end, we are leaving the mummies intact on the plant and watching for their emergence to begin so that we can distribute the gravid female wasps amongst populations of C. cirripediformis throughout the Orchid Center.

Over the course of two years, we have identified a variety of thrips which, for the purpose of control, fall into two categories. There are those that pupate in the soil layer: Flower Thrips (Frankliniella spp. and Orchid or Anthurium Thrips (Chaetanaphothrips orchidii Then there are those that pupate on the above-ground portions of the plant: Greenhouse Thrips (Heliothrips haemorrhoidalis Poinsettia Thrips (Echinothrips americanus), Banded Greenhouse Thrips (Hercinothrips femoralis), and Redbanded Thrips (Selenothrips rubrocinctus). I say “for the purpose of control” because thrips life cycles are particularly troublesome. Eggs are laid underneath the cuticle of the plant, protecting them from predators and insecticides. Larvae usually develop on the undersides of leaves, shielding them from view as well as from foliar sprays that fail to be thorough. Here is where it gets troublesome: some thrips will leave the plant to pupate in the top layer of the soil beneath, while others remain as prepupae and pupae on the plant surface. For the species that pupate in the soil, entomopathogenic nematodes, such as Steinernema feltiae, are very effective at interrupting the generational cycle and causing the population to crash. We began to

apply these nematodes as a soil drench monthly in our collections greenhouse and have not detected any soil-pupating thrips outbreaks in our collections since. These nematodes, unfortunately, are very sensitive to UV light and have limited effectiveness in foliar application. Additionally, it has been our experience that the species which pupate on the plant itself are not the preferred prey of predatory mites which are so often employed in thrips control programs. This is especially true of the later stages of those thrips- they are just too robust for the smaller mites to handle (and they tend to fling fecal droplets at predators to deter them). The one benefit we have seen is that the presence of mites on plant material prior to the arrival of the adult thrips seems to discourage population establishment on that plant. For this reason, we keep slow-release sachets of the predatory mite, Amblyseius swirskii, in our spaces year-round. The only places we are finding new populations of thrips like E. americanus and H. haemorrhoidalis are where we failed to preempt the arrival of adults on those plants. Prophylactic use of these mite sachets has had the added benefit of controlling some phytophagous mites that had been perennial pests in some of our Dendrochilum, Sobralia, and Spathoglottis specimens.

When you consider that many predators and especially parasitoids are more susceptible to pesticides, even at levels sublethal to pests, it becomes especially important to be careful with broadcast application of pesticides. You may inadvertently wipe out established populations of biocontrols that are working behind the scenes on your pest problems. In the interest of leaving refugia for our beneficials, both artificial and natural; we target specific, individual plants that need intervention while leaving others with lower levels of pests untouched. This preserves some of the enemies of those pests as well as their food source (or host) and allows the

In the absence of heavy, sweeping pesticide applications; we began to see robust populations of parasitoid wasps take on troublesome pests that had resisted our control efforts in the past. Aphids were often colonized and largely mummified by the time we found them. The hollow cavities of scale could be seen through perfectly round exit holes across the FOC. Even miniscule thrips eggs were falling victim to Chalcid wasps. The next step in supporting our beneficials is providing them with habitat and, more importantly, getting them where we need them to go. Initially this can be accomplished by relocating colonized plant material to as of yet unaffected pest populations. However, we in the FOC have begun the process of identifying and cultivating banker crops that can be seeded with both pest and parasitoid. This plant-pest-parasitoid complex can then be placed near emerging outbreaks of the target pest to establish control before the population can spread or cause significant damage.

Banker crops are not a novel idea in the world of IPM, but they have been largely developed for agriculture or production. Our greenhouses represent various tropical understory environments and do not provide the optimal growing conditions for many tried and true bankers to be successful. One reason is because many banker systems rely on the vigor and flowering capacity to attract and retain beneficials, but our collections need a slightly lower light level than most known bankers. This has led us to investigate other potential banker crops that integrate better into our displays and collections by still producing the necessary vigorous growth, pollen and nectar food sources, and desirable habitat for reproduction. One method I’ve found successful has been to release the beneficial organism broadly throughout a space and observe closely for the following weeks to see where they stick around. Reproduction takes longer to observe since you must wait for eggs to hatch and juveniles to mature enough to be seen. Occasionally you will be rewarded by finding a favorable habitat built right into your space that will produce successive generations of biocontrols, saving you the time and expense of repeated releases.

One such crop is a group of compact, mounted Platycerium bifurcatum. A large specimen, high up on display in the FOC’s Orchid Display House, was found with a hefty population of Brown Scale, Saissetia coffeae, as well as an associated parasitoid wasp. The scale was only noticeable when cleaning up old fronds as they dropped because the plant did not seem to be overly impacted by the scale’s feeding. This provided the parasitoid wasp with the perfect, stable host population. As fronds would drop with mummies intact, I placed them around the FOC amongst populations of S. coffeae that did not yet have any parasitoids controlling them. Inoculating scale populations in this way allowed us to bring all populations of this particular scale below our threshold for damage and display-worthiness. We are now in the process of growing on some smaller, more mobile P. bifurcatum to inoculate with the same complex of S. coffeae and parasitoid wasp. They will then become modular bio-bombs that we can deploy near emerging outbreaks of S. coffeae and other scale hosts to hasten their demise. The parasitoids would likely have found the scale eventually, but almost 11,000 squarefeet of greenhouses can be a lot of area to cover for a very tiny wasp on its own tiny wings.

A thrips predator about which we are optimistic is Dicyphus hesperus. It is one of those predators which provides good control but needs suitable habitat to survive once they have ripped through their prey population. The classic banker for this predator is Common Mullein, Verbascum thapsus D. hesperus will supplementally feed on V. thapsus and lay its eggs on the plant, allowing it to sustain a colony of the predator when prey levels are low. Egg laying can further be improved by feeding with the frozen eggs of a moth, Ephestia kuehniella. However, this biennial will not grow best in the understory of the FOC. An alternate banker for this predator, observed by our colleagues at the Insectarium of Montreal’s Space for Life, is Rhytidophyllum auriculatum, a tropical flowering plant in the Gesneriaceae family. And while we don’t have that exact species, the Garden is fortunately home to a beautiful gesneriad collection which includes another member of the same genus, Rhytidophyllum exsertum. We tested this species’ fitness as a banker plant by propagating several plants of varying sizes and introducing D. hesperus adults. Fed with a regular supply of thrips from pruned cuttings of infested plants, the predator survived and reproduced on R. exsertum. We plan to augment our crop of potted R. exsertum in the coming year so that we can establish a self-sustaining colony of D. hesperus for periodic distribution amongst outbreaks of otherwise difficult-to-control thrips. In the meantime, we are growing a bank of V. thapsus in a bright spot in one of our greenhouses and distributing the R. exsertum amongst them. This should provide sufficient surface area for a robust population of D. hesperus to establish and aid in thrips control. We may even be lucky enough, over successive generations, to develop a population of predators that thrives on the R. exsertum as well as it does on V. thapsus.

With ever-diminishing access to conventional pesticides, a growing concern for environmental impact, and the looming threat of climate change; there is an increasingly urgent need to adopt more resilient pest management systems. In the pursuit of better biocontrol, we are developing more sustainable horticultural habits: reduced reliance on chemical controls, accurate identification of pest issues, more intentional planting, individualized care, and more precise physical controls, among others.

By creating an environment that leverages our pests’ natural enemies now, we are setting ourselves up for success in the face of challenges to come.

BY SARAH CARTER, Orchid Horticultural Curator

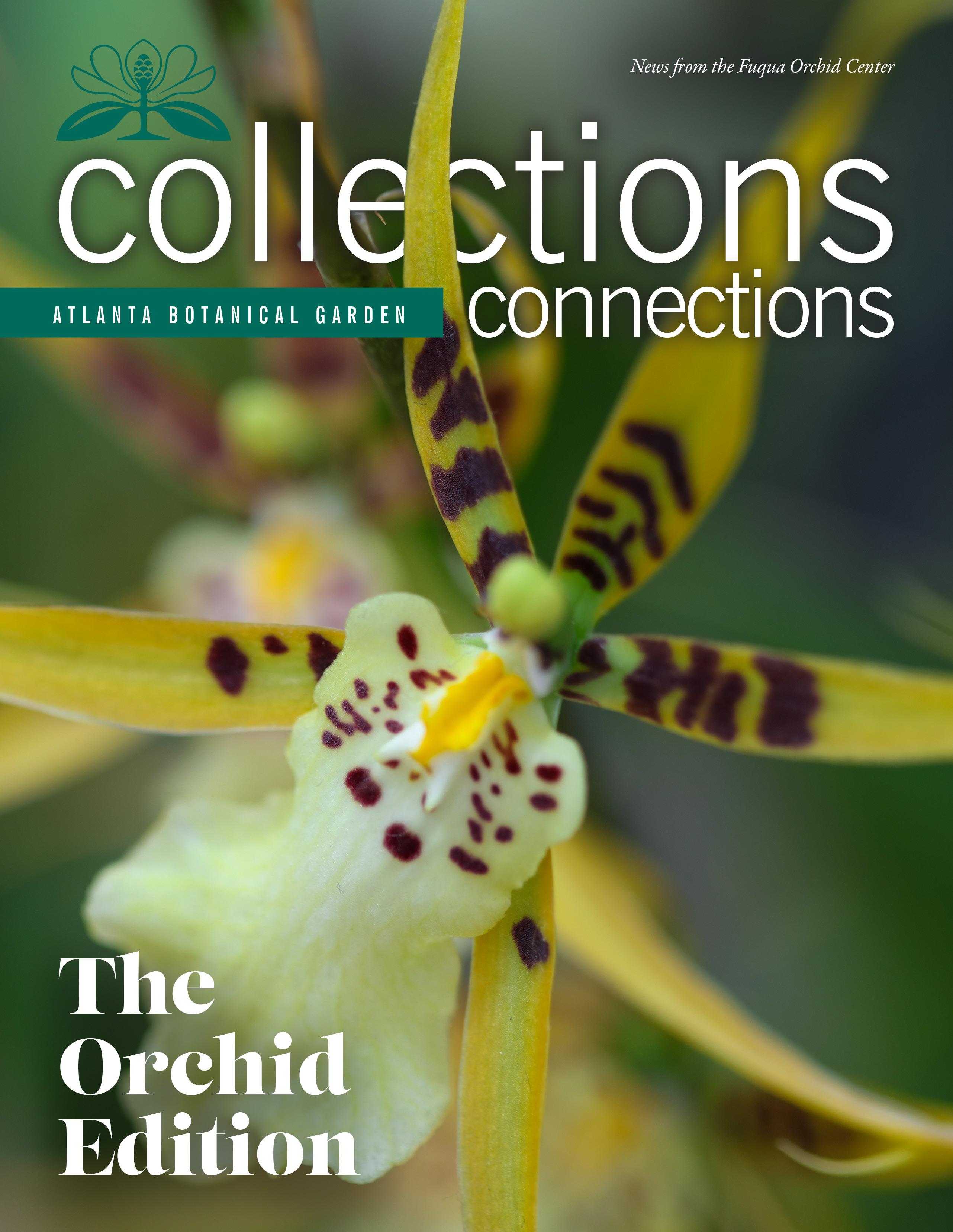

Every January, after the holiday music stops and the poinsettias are cleared out, the Orchid Center is transformed into an exuberant celebration of the plant family for which it exists. For over two decades, Orchid Daze has given visitors a colorful escape from chilly late winter and a chance to appreciate the great beauty and variety of tropical orchids. Found in the Fuqua Conservatory Lobby, the Orchid Atrium, and the front section of the Orchid Display House, Orchid Daze typically runs for eight weeks from mid-February through midApril and is included with admission to the Garden.

Each year brings a different theme or motif for the show. Early shows highlighted geographical themes. Some shows like Surreal Beauty, Lasting Impressions, and Pop! were inspired by art movements. Others have explored the use of vertical space (Hanging Gardens and Towers of Flowers), water (Liquid Landscapes),

fabric, and even unique forms made with grapevines (Nature’s Wonders). One year we drew inspiration from the work of Mexican architect Luis Barrigan. In other shows we have collaborated with and incorporated the work of local artists including murals, glass, metal sculptures, and photographs. This year with Reflections in Bloom, we dazzled our visitors with the colorful, mosaic-like “assemblages” of Atlanta artist Lillian Blades. Whatever the theme or artwork in the show, we always strive to present its hundreds of companion orchids in a complimentary and creative way.

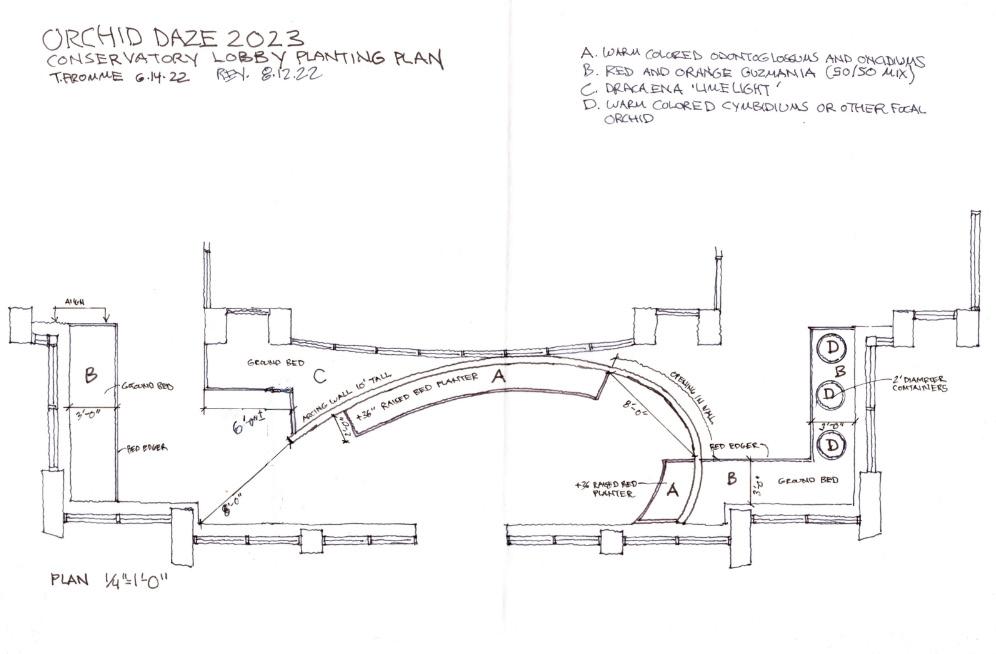

Our visitors may not realize it, but Orchid Daze takes nearly the whole year to come to life. We start our planning for the next year almost as soon as the current year’s show comes down. It starts with brainstorming sessions among our Orchid Center and exhibits teams along with our independent designer Tres Fromme from 3 fromme DESIGN. Tres has worked with the Garden

on Orchid Daze for 18 years, so he is very familiar with our spaces, our budgetary constraints, and the aesthetic that we hope to achieve. It is no easy task coming up with new ways to repeatedly transform the same three spaces with new and interesting ideas. We look for inspiration in pictures of artwork from potential collaborators, interesting art installations, buildings, and images that we find online. Sometimes our ideas are little out-there, but eventually we settle on something that we all can get excited about.

Once we have a good sense of what we want to do, Tres gets to work making concept sketches to put our general ideas onto paper. With concept sketches in hand and some more time to think about it, we have more meetings to refine our ideas, talk about materials, and make sure it is something we think we can execute well and within budget. If our show includes artwork, our exhibits team works with the artist to either

choose existing pieces to use, or to design custom pieces just for our show. One thing we always have to keep in mind is that our display spaces have constant high humidity and of course, plants need water. All the structures and artwork must be able to withstand what are essentially outdoor conditions.

Around August or September, the design is further fleshed out, including detailed floor plans that include measurements for structures and specific planting suggestions. We also will have started the “mock-up” phase of Orchid Daze. To me, this is one of the most fun parts of the whole process. This is when we really get into the creative problem solving required to take a somewhat ambiguous idea and make it real. This gives us the opportunity to try out different materials and techniques we think we might use way ahead of time so we can avoid last minute problems.

For instance, for our Surreal Beauty show we made “shoe trees” for the Orchid Display House. These were small cut trees covered in lace to which were attached brightly colored, high-heeled, platform shoes. In each shoe was planted a single slipper orchid (Paphiopedilum or Phragmipedium) accented with moss. We had to put a lot of thought into how we would take this wild

idea from concept sketch to reality. We ordered a few pairs of inexpensive shoes in different sizes to experiment with. How would we provide drainage? Would the material of the shoe become stained or moldy over time? How could we prevent too much water damage to the shoe? What is the least visible way to attach the shoe to the branch? What is the most attractive and waterproof way to attach lace to a tree?

Another example is when we did a show that included using giant grapevine spheres to display Miltoniopsis and Cattleya hybrids. How would we sink the orchid pots below the surface of the sphere? How would the ones on the bottom of the sphere get water? How could we do this in a way that made it easy to switch out the old orchids with fresh ones during the show? How would we attach live sheet moss to the spheres in a way that wasn’t too visible? What was the least complicated, most inexpensive, but effective way to do all this? All these questions needed to be answered before it was time to actually install the spheres.

When working out the details for any given element of a show, there are certain considerations we always need to keep in mind. The plants usually stay in their pots since minimal disturbance to the roots helps with longevity, we often have to switch

out faded flowers with new ones during the eight weeks of the show, and leaving them in pots saves time and labor. This means finding different ways to hide the plastic pots. Good drainage is, of course, a must. We also have to be mindful of overhead water. Will the design cause plants underneath a structure to rot because the plants above them need water frequently? For vertical or hanging elements, we have to consider the height at which the plants will be displayed since heat and light become more intense the higher you go in a greenhouse. We try to think through every aspect of the design while we still have time to address it.

Come fall, we begin to look at our planting plans. In the Orchid Center, our main focus is on our large species orchid collection, but for Orchid Daze we buy in hundreds of hybrid orchids for the display. We try to use as many different hybrids as we can get and that will do well in our conditions. Oncidium and Cattleya intergenerics, Dendrobium, Paphiopedilum, Phalaenopsis and Vanda from California, Hawaii, and Florida are yearly stars of the show. Our designs will often just indicate a color palette and height for our orchids so that we can be flexible with what’s available from our vendors. We frequently use a broker to obtain our orchids from a

shrinking pool of commercial orchid growers struggling under high demand. Similarly, we choose our companion foliage plants based on availability, habit, color, and cultural requirements. There are always substitutions that have to be made when some plants become unavailable. Once we have hammered out the details of the planting plan, we begin estimating quantities, placing orders and scheduling deliveries as well as gathering any other supplies we might need.

Meanwhile, our Exhibits team is busy with logistics, planning for the construction of the structural part of the display, having elements fabricated, and scheduling the installation of the artwork if needed. Our education department also starts gathering information and writing the signage and interpretation. This sometimes includes interviewing the artist if there is one and recording segments

for an audio tour. Our marketing team takes photos and designs the promotional material, signs, and information displays which will greet our visitors in the Orchid Center Gallery and enhance the experience of Orchid Daze.

Finally, in mid-January, it’s time to bid farewell to the holiday season and start the three week Orchid Daze installation. We start with a detailed installation schedule. Then, something comes up and we have to rearrange the schedule. This can happen many times throughout the installation. Sometimes vendors can’t come through with plants we thought we were getting, or some part of the construction is delayed, or helpers call out sick. Given a tight timeline (we still have to do our regular jobs while all this is going on), our limited space and lack of staging areas (the spaces stay open to the public for

the most part), the installation can become a complicated puzzle. Yet, we always manage to pull it all together in the end. The creation of each Orchid Daze offers new lessons for future displays.

The best part of Orchid Daze is when, at last, our visitors get to see the result of nearly a year’s worth of effort by the many people who made it happen. We get to combine our love of orchids with our artistic creativity and our visitors get to see orchids like they’ve never seen them before. Then, when the show is over, our visitors get to take a little piece of it home when they buy the orchid hybrids and foliage plants at our Gently Used Plant Sale. We install our summer display and start planning for Orchid Daze all over again.