Re-membering Through Narratives

A review by Durkhanai Ayubi1 and Dana Walrath2

Senior Atlantic Fellows

1 for Social Equity

2 for Brain Health Equity

2020

A review by Durkhanai Ayubi1 and Dana Walrath2

Senior Atlantic Fellows

1 for Social Equity

2 for Brain Health Equity

2020

“To all the stars covered in a blanket

The ones who fail to love their reflections because the world holds the mirror Hate disguised in indifference is testimony to your power

Your star will blind them all.”

Hadassah Lewis (pen name) AFSEE Fellow from Bow to Enter Heaven

We are born. We live. We die. As in a story, each individual life follows a narrative arc. This life unfolds in relation to others we have ancestors, and we will become ancestors. We inherit our story from those who precede us, and we leave stories open for shaping by those who follow us. We are each but a point in a perpetual conversation linking everything that has been with all that is yet to come.

Perhaps this accounts for the capacity of narrative to shape us. Narrative connects us to our histories, while generating the echoes of ourselves which will be felt in the future. It shapes our interiors and our social interactions. As we create and share meaning through story, we establish our values and our cultural norms our realities. Functioning on both the individual and collective levels as well as in conscious and subconscious realms, stories maintain and naturalise individual patterns as well as particular social orders, including those based in systemic and structural injustice. This same capacity of narrative to normalise and naturalise also lies at the heart of stories’ ability to create vast personal and social change once uncoupled from the prevailing dominant narratives that silence, oppress, and justify global inequities.

This capacity makes narrative integral to the Atlantic mission. Narratives determine whether our world will normalise equity or inequity. They are a construct based on the choices we make their direction is not inevitable. We believe that our world today and the challenges which riddle it, derive in large part upon the long, active, and powerful generation of narratives which have privileged notions of exclusion, categorisation, and undue acquisition. Often hidden, yet embedded systematically into all the structures of our lives, these narratives create social norms which marginalise and violate people the world over while benefiting an increasingly shrinking elite.

Influenced greatly by the norms embedded within the imperialist conquests of the last five to six centuries, these dominant narratives represent a largely singular voice which privileges only certain modes of knowledge and deems only particular experiences as legitimate. Their censoring and suppressing force has created a reality which denies the full spectrum of experiences and wisdom that constitutes our shared human story.

Today’s gaping global inequity demonstrates the inability of these falsified, but dominant, narratives to adequately reflect our societies, express our concerns or to capture our hopes and dreams. The tangible dissatisfaction with, and rejection of, the stringent and divisive systems such narratives have normalised, reverberates globally. In such a world, these fabricated and brittle confines can no longer contain the enormity of our multitudes and the breadth of our horizons. In many ways, the rupturing impact of COVID-19 and the systemic injustices it has plainly revealed, have amplified efforts towards unmasking the insidiousness of the censorship and denial long made possible by deeply engrained systems of inequity. With awakened lucidity, we see not only the sedating effects of the falsified narratives which dominate our world, but we can reject them for their inability to adequately buoy us into the futures we know are possible.

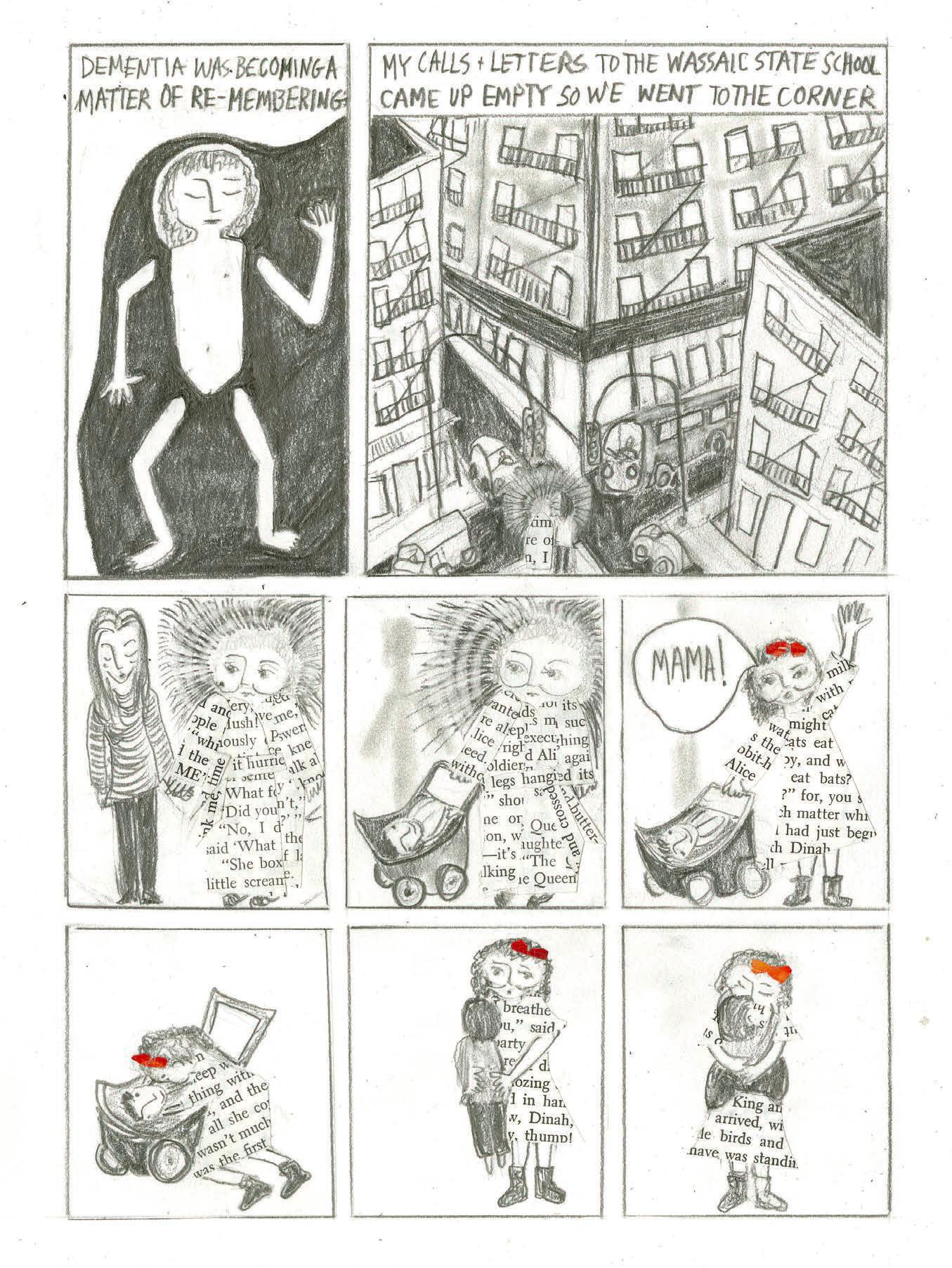

To navigate our way to our unbound possibilities, we emphasise of the notion of “remembering” a process of becoming unified and whole. Re-membering depends first upon the act of conjuring the intrinsic memories of ourselves beyond the distortions our histories would have us forget. Next, we reassemble the pieces of ourselves that were dismembered and forcibly removed, to generate a vision that is unified and whole.

In this moment in our collective human story, we have arrived at a precipice which beckons us to re-member into being a different world a world that, we posit, if long held at bay, has nonetheless always been known to us.

It is a world that is held within the multitudes of stories and unbridled acts of grace, interconnectedness, unity, and determination that constitute a significant portion of our shared histories, and which intends to reject dogma and to uphold our shared human dignity.

These ways and stories perhaps have never sought recognition or dominance with the same reckless and blunt force as authoritarian visions of power, and thus may be dismissed as less viable ways to imagine our world. But these precise traits not to conflate an untamed ego with power, not to encourage the atomisation of ourselves from our own ancestries and from one another, and not to laud hierarchical and controlling ways as necessary for maintaining order give these narratives an emancipatory and enduring vision of power aligned with our deeper natures. The time for narratives which allow our deepest selves to bloom, and for the connections of our communities by notions of dignity, is long overdue.

Re-excavating, re-membering, honouring and implementing ever-present (but long-negated) parts of our nature into the visions that form our societies is a home-coming that has the potential to transfigure our collective narratives, and thus our world, and the world of all those yet to come.

We acknowledge and emphasise that this review does not intend to be (and could never be) an account of every grievance endured by those who have been pushed to the margins through narratives designed to compartmentalise. We attempt to provide instead, an analysis

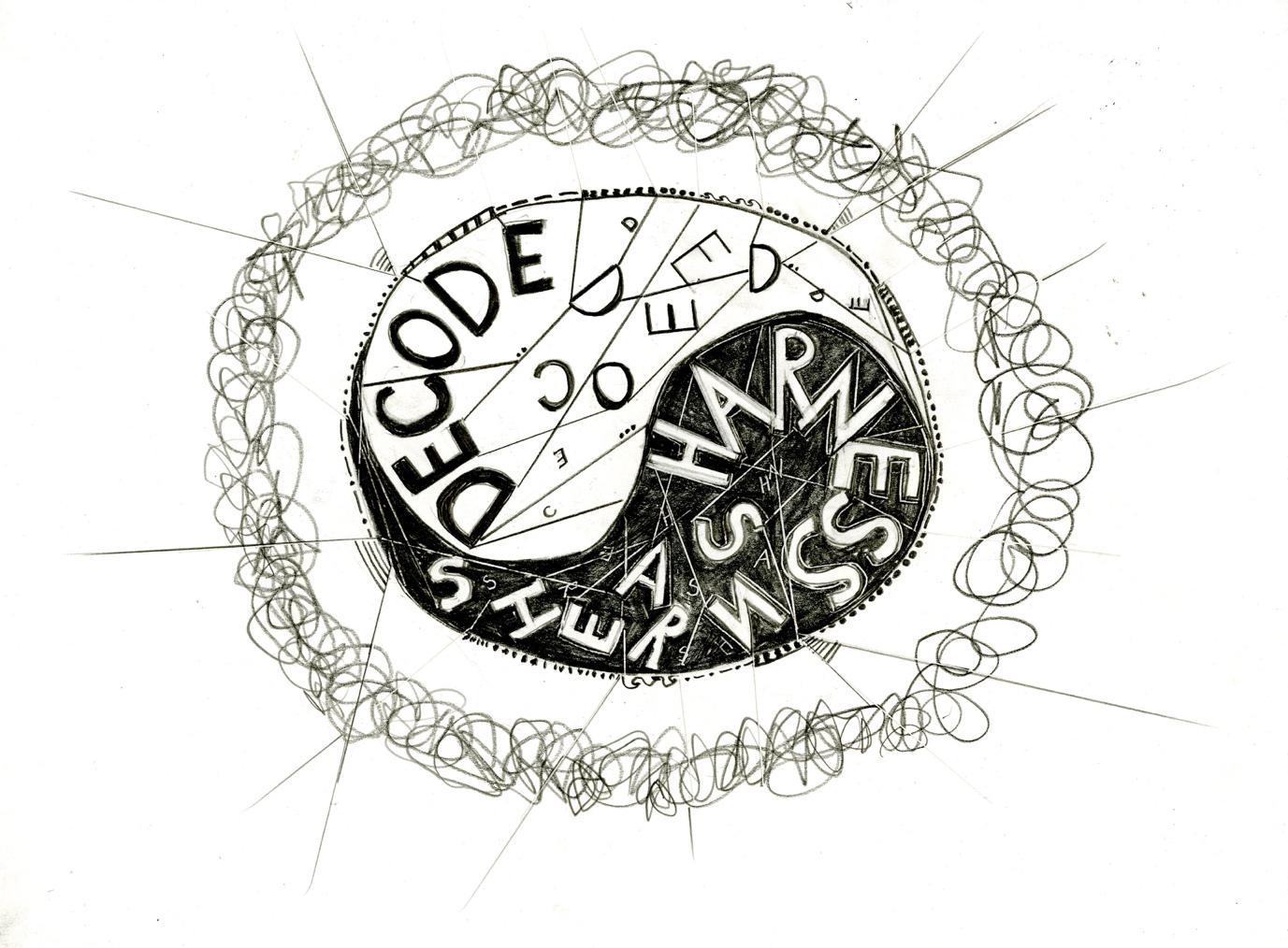

of the themes and patterns which have emerged in narratives over time that led to the unjust systems and norms known to many of us in our own deep and intimate ways. Understanding how these patterns unfold and how they connect to form a web of inequity, allows us to decode and contextualise where we sit in this moment in history and to broaden our appreciation of how, so often, seemingly disparate injustices are knitted together using the same narrative thread. This allows us to crystallise a clearer picture of ourselves and one another, enabling us to direct our energies into generating narrative norms which not only amplify the work we each carry out within our respective communities, but which simultaneously unravel the knots that stitch together the broader fabric of injustice.

In this review, we begin to posit how, as a community, we can harness narratives to enact what this moment requires. To us, narratives are not just a skill set to be mastered within an organisation, but a reflection of the deeper value systems and interpretations of power by which societies choose to abide. Through a critical assessment of academic and nonacademic literature, other communicative forms, and the use of narrative by other social justice organisations, this review seeks to articulate the particular strengths of an Atlantic approach to narrative. We take a long view, deeply cognisant of the histories which have brought us to this moment. We believe that such critical analyses of dominant narratives equip the Atlantic community to undertake the necessary work of generating sentiment, rather than forcibly reacting to the damaging sentiment set by others. Such re-membering makes a transformation of the values which underpin our present conceptualisation of power and systems of exchange, along with the injustices they maintain, possible.

We begin with unpacking the distorting impact of accounts of history recorded through a singular lens that has normalised narratives that essentialise and categorise the human experience. We move to explore how this history has created the inequitable systems and social norms which define our present. We then explore what we might approach differently to the already numerous and resounding approaches to social equity emphasising the need to stay alert to the potential trap of replicating sentiments of oppression even in narratives of liberation, and the opportunity to harness the unique and potentially powerful suite of traits already encoded within the Atlantic mission and its Fellowships. Finally, this review provides initial recommendations for further exploration on how we might use our knowledge and our position to carry out the necessary and timely work of shifting the detrimental dominant narratives that engulf our world.

We endeavour to open multiple pathways cognisant of the present toxicity of narratives that have generated a world which is hostile to our own humanness, to one that nurtures a reality that better reflects our experiences, and which is geared towards liberating our boundless human potential.

This report outlines the beginnings of why and how.

“Contrary to what the colonial project has intended, as Africans, we have a responsibility to shift our focus continentally to build solidarity with efforts to break silos and divides that exist across diverse African contexts and to re-orient African knowledge, realities and people as valuable and legitimate knowledge bearers.”

Shehnaz Munshi, Lance Louskieter

Kentse Radebe AFHESA Fellows

The problem of history is that it normalises an account of ourselves that is hierarchical, racist, gender biased and generally disembodied from the natural cycles of the universe we inhabit. This account of history and the narratives it has normalised has generated into existence a world that does not reflect the fullness and the depth of the experience of being human. From this schism this abyss generated by the incongruence between essentialised narratives which shape our world and our deeper, more interconnected nature mass inequities and injustice have unfolded in ways that place crippling limits on the lives of many across our globe.

We build our histories and accounts of ourselves through narrative. Pueblo Native American scholar, Gregory Cajete, writes “humans are story telling animals. Story is a primary structure through which humans think, relate and communicate. We make stories, tell stories, and live stories because it’s such an integral part of being human…myths, legends and folk tales have been cornerstones of teaching in every culture…the myths we live by actively shape and integrate our life experience. They inform us as well as form us, through our interaction with their symbols and images”.1,2

From the ancient creation stories and rites of Indigenous cultures, through to the notions of the duality of light and dark embedded in the millennia old Zoroastrianism and Taosim through to the countless stories told within societies, communities, and families, narratives drive the trajectory of the perpetually unfolding human experience.

1 Cajete, G. (1991). Look to the Mountain: An Ecology of Indigenous Education, Durango: Kivaki Press, p 114

2 Given the importance of multiplicity of voices, we provide to the best of our ability, the cultural heritage of each of our sources along with their current country of citizenship. We recognise that all existing national borders were drawn by those with power as they came to dominate various parts of the earth.

These shared stories bind us to one another in continuity, and form the basis of our realities, acting in a way that is two-fold: firstly, by helping us to decode and understand our world, and secondly, as a means that we harness to build the ideologies that actively shape our world. This act of decoding and harnessing narratives works in unison to generate the basis which underpins our realities (Figure 1).

This two-fold capacity of narratives innately connects them to power: the values and the ideologies we arrive at through our stories and our sensemaking, then infuse the key decisions we make that span across our societies. Narratives position us collectively (in conscious and often subconscious ways) on fundamental issues, such as: how we locate our human experience within cycles of the overall cosmos; how we respond to differences between us particularly in a world where we live in closer contact than ever; and our relationship to death and the concept of our mortality. The values we arrive at through our narratives on timeless and pervasive issues such as these, then decide what our tangible world looks like determining the level of equity and justice embedded within our cultures, politics, institutions, and principles of resource distribution.

But what happens when the narratives which shape our increasingly interconnected world become trapped in a reductive lens, distorting both how we understand and how we shape our world?

A brief analysis of the genealogy of narratives over time, brings us to this precise precipice: a world deeply troubled and dispirited by centuries, if not millennia, of narratives that devalue the multiplicity of voices and experiences which form our histories in favour of an essentialised view of what and who matters, driven most perhaps by an increased desire and ability to funnel resources to a centralised powerful elite.

Welsh historian Amanda Rees, explains the tendency for ‘big histories’ towards “distilling the many voices of humanity’s past into a single human story”.3 Similarly, in his book The Archaeology of Knowledge, French philosopher Michel Foucault writes “in short, the history of thought, of knowledge, of philosophy, of literature seems to be seeking, and discovering, more and more discontinuities, whereas history itself appears to be abandoning the irruption of events in favour of stable structures.” In other words, a consequential discrepancy exists between our lived realities and the essentialised version which official accounts of history normalise into indisputable truths. These ‘indisputable truths’ gain undue gravitas and longevity through their means of transmission. Predominantly by preference given to the written word, these essentialised accounts dominate the narratives provided through the curriculum of prestigious learning institutions, global media, academic literature, voluminous books, and through a dogmatic reverence to rationalisation, codification and scientific research.

Throughout his works, Foucault establishes the connection between power and knowledge. Foucault recognised that power is based on knowledge and makes use of knowledge, and that simultaneously, power reproduces knowledge by shaping it in accordance with its own intentions. Similarly, education theorist and professor, Michael Apple, writes extensively about the implication of education (which includes formal curricula, but also media and other modes of knowledge transference) in the politics of culture, instead of viewing it as a neutral assemblage of knowledge. Apple writes “the decision to define some groups’ knowledge as the most legitimate, as official knowledge, while other groups’ knowledge hardly sees the light of day, says something extremely important about who has power in society”.4 Apple challenges even the notion of ‘common-sense’, itself filled with patriarchal language and void of acknowledging the marginalisation that people suffer. He argues that the use of particular narratives by “blocks of neoliberalists, neoconservatives, authoritative populist religious conservatives, and a professional and managerial class (who believe in measuring

3 Welsh, A. (2020). Are there Laws of History? [online] Aeon.co https://aeon.co/essays/if-history-was-morelike-science-would-it-predict-the-future

4 Apple, M. (1993). The Politics of Official Knowledge: Does a National Curriculum Make Sense? Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 14(1), pp 1-16

everything) pushes educational and cultural work in particular directions to transform societies”.5 The direction of these pushes, as we explore in this review, serve to normalise a world that privileges only certain experiences, based on the ‘common sense’ determined by those whose narratives are seen and heard.

Stratification arises from such an eclipse of the multiplicities of experiences that constitute the human story. This eclipse also renders the consequent prevalence of biases and inequities so tangibly manifest today, a natural human social condition. Throughout this review, we argue that these discrepancies do not inescapably derive from our innate natures and see the prevailing inequities as a consequence of our choices and our constructs of the narratives to which we subscribe.

The 2.5 million year archaeological record shows that inequity came to humans quite recently. Its earliest glimmers arrived well after the beginnings of the domestication of plants and animals and sedentism some twelve thousand years ago, the social changes that allowed humans to begin to store and produce goods. Early writing systems appearing five to eight thousand years ago functioned to maintain the first social stratifications distinctions of wealth and power by recording the exchanges of material. Inequities intensified with the first so-called civilizations which began as a form of human social organisation a mere three to five thousand years ago. This change set some human societies on paths that linked technological innovation with the ability to amass capital and to control others. Writing, a capacity of privilege, went on to document the glory of wealthy rulers. This stratified social form tainted even the beginning of democracy in Ancient Athens where only a distinguished group of property-owning men held sway.

While dominating civilizations appeared throughout the globe, much of the tone of the injustice that grips our world today traces its origins to the devastating and far reaching impact of centuries of Euro-American imperialism. Closely related to this imperial conquest, came advances in the science and technology of travel and warfare as well as the invention of the early printing press and the accompanying ability to widely disseminate the written word, carrying with it an unprecedented capacity to entrench a skewed balance of power. The distortions generated over these centuries not only persist to this day but have again, in many ways been compounded.

Part of the impact of this skewed world view stems from the creation of a symbiosis between authority and the indisputability of the narratives it espouses, so close, that we mistakenly assume these narratives to be preordained or inevitable. In his book Orientalism, Edward Said, Palestinian American scholar and founder of postcolonial studies, asserts “there is nothing mysterious or natural about authority. It is formed, irradiated, disseminated; it is instrumental, it is persuasive; it has status, it establishes canons of taste and value; it is

5 Artsequal.fi (2018). Arts Equal website. [online] Available at: https://www.artsequal.fi/-/michael-applenstudia-generalia-luento-kansallismuseossa-22-10-/2.9

virtually indistinguishable from certain ideas it dignifies as true and from traditions, perceptions, and judgements it forms, transmits, reproduces” (p 20).6

In Orientalism, and in his later expanded work Culture and Imperialism,7 Said’s central thesis explains how an entire world of ‘others’ was created as a necessary element for the justification of European conquest and acquisition of far flung lands. Beginning with the maritime expeditions from the Iberian Peninsula in the fifteenth century, along with those of the Dutch, British and French, through to the more recent American agenda of military expansionism, these imperial conquests unleashed grave injustices and violations of human dignity. They were, in turn, facilitated and normalised by a history of narratives that assumed ordinance over entire populations throughout Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Australia and beyond. Through the power of military and scientific accounts as well as through cultural and literary works, encountered populations were rigorously dehumanised to shadowy and subaltern figures, ripe for control and made for subservience.

The works of writers such as Flaubert, Kipling, Austen and even as far back as Homer, as well as the accounts of Egypt by conquerors such as Napoleon, act in concert to subordinate the rest of the world as a natural ‘appendage’ of the West. As such, Said writes in Orientalism, these accounts serve to “divide, deploy, schematize, tabulate, index and record everything in sight…to make out of every observable detail a generalisation and out of every generalisation an immutable law” (p 86). Critically, Said writes “the power to narrate, or to block other narratives from forming and emerging, is very important to culture and imperialism”.

The blocking of the narratives of others functions to normalise inequities in our world. This eclipsing is carried out in a number of ways associated with the control of narratives that normalise falsified realities, including, but not limited to: devaluing all knowledge not considered rigorously legitimate enough thereby discounting intuitive knowledge and dismissing the oral and expressive traditions which for millennia have powerfully transmitted culture from one generation to the next; providing consistent accounts of the non-Anglo world and its people as subservient and unable to resist being ruled; and normalising narratives of hierarchical worth in which a select group of people are privileged above all others, and also above the natural world. Encapsulating this normalised erasure of the multitudes of experiences that constitute our realities, in Culture and Imperialism Said affirms with clarity, “one of the canonical topics of modern intellectual history has been the development of dominant discourses and disciplinary traditions in the main fields of scientific, social, and cultural inquiry. Without exceptions I know of, the paradigms for this topic have been drawn from what are considered exclusively Western sources” (p 47).

Reflecting this single capture of history, Mohawk Native American scholar Michael Doxtater writes about the ‘Euro-master narrative’ that directs the cycles of knowledge and power that

6 Said, E. (1978). Orientalism, London: Penguin

7 Said, E. (1993). Culture and Imperialism, London: Chatto & Windus

regulate our world. This master narrative springs forth from the belief that, unlike all other narratives, Eurocentric knowledge leads towards progress. This Foucauldian ‘colonial-powerknowledge’ relationship, according to Doxtater, “communicates particular cultural presuppositions that elevate Western knowledge as real knowledge while ignoring other knowledge”.8 The tone of this singular narrative, and the quest for control it has normalised, is powerful enough to dictate the shape of our entire world. It generates an essentialised and sweeping views of the world developed and advocated for by British historians like Eric Hobsbawm as a ‘world-system’.

This world-system, Doxtater analyses, “was born from imperial and colonial progress and the rise of nation states in liberal modernity. The world-system of nation-states cut across geographic and cultural demarcations with political boundaries.”9 This demarcation of the world, which ignores long-standing cultural affiliations and relationships with the environment, in favour of Western political advances, helped to build capitalist empires, through redirection of resources from their localities to within the borders of ruling nations. This cutting across, this eclipse of all other knowledge and encirclement of people, created a single pervasive narrative structure that, through its persistent homogeneity, undermines and places limits on our true collective progress. To this effect, Doxtater writes “posing as the fiduciary of all knowledge exposes the limits of Western knowledge”.10 Similarly, Indigenous Bunurong, Tasmanian, Yuin heritage Australian writer Bruce Pascoe identifies this pernicious Euro-master narrative stating, “we should be wary of locking ourselves into the assumption that everything is driven by superior Western minds and tools on an inexorable march of conquest, as if that is the only way a species might evolve” (p 195).11

The pinnacle of Western knowledge itself is encapsulated historically by what is broadly known as The Enlightenment era, taking place from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. This era, known for progress driven by the separation of scientific thought from religious doctrine, shaped the work of philosophers like John Locke, and more broadly, set the cataclysmic shift towards espousing universal liberty and equality amongst humans into motion. But deeply entrenched within the ideas of progress driving many of these iconic thinkers and the tone of the era, was a paradoxical denial of the right to life and liberty of those being colonised and enslaved. Locke was himself a colonial administrator and an investor in the slave trade. Other key enlightenment thinkers, like German philosopher Immanuel Kant, still considered one of the most important Western philosophers, wrote about reason, ethics and virtue on the one hand, while sketching out some of the first and most detailed hierarchies of race on the other. Kant writes “humanity is at its greatest

8 Doxtater, MG. (2004) Indigenous Knowledge in the Decolonial Era, 28/3, American Indian Quarterly, pp 618633

9 Ibid

10 Ibid

11 Pascoe, B. (2014). Dark Emu, Broome, Western Australia: Magabala Books

perfection in the race of the whites. The yellow Indians do have a meagre talent. The Negroes are far below them and at the lowest point are a part of the American peoples”.12

This irony and the suffering it triggered was not lost on the many whose oppression was simultaneously being justified by a movement of thought supposedly dedicated to human liberation. Haitian writer Baron de Vastey (1781-1820), brought this perspective into his chronicles of the Haitian revolution and the era of French colonisation of Haiti (1659-1804). In a book titled Baron de Vastey and the Origins of Black Atlantic Humanism, African Diaspora historian Marlene L. Daut highlights Baron de Vastey’s awareness of how the Enlightenment era thinkers categorised all objects, including plants, birds, rocks, and flowers. This paved the way for the racial taxonomies that place White Europeans at the top of humanity and Black Africans at the bottom, justifying racial prejudices and practices such as slavery. In an interview on her book, Daut states, “the Black Atlantic humanists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, of which Baron de Vastey was a distinct and important part, contested this so-called Enlightenment by revealing it to be utterly devoid of the humanity in whose name it was developed and proclaimed.”13

Similarly, providing one of the West’s first reckonings with Europe’s violent 20th century of war, genocide and racism, German-American political theorist Hannah Arendt observes in The Origins of Totalitarianism, that through the conquests across Asia, America and Africa, it was Europe which reordered “humanity into master and slave races”. Such ordering rooted in the science of classification which flourished in parallel with the colonial conquest thus granted scientific authority to the racist overlay when it appeared.

Reflecting on this connection between imperial power and its deliberate establishment of racially defined hierarchies, Indian author and essayist Pankaj Mishra writes “this debasing hierarchy of races was established because the promise of equality and liberty at home required imperial expansion abroad in order to be even partially fulfilled…Racism was and is more than an ugly prejudice, something to be eradicated through legal and social proscription. It involved real attempts to solve, through exclusion and degradation, the problems of establishing political order, and pacifying the disaffected, in societies roiled by rapid social and economic change.”14

Consistent with the ability to create narratives, but critically to also block narratives from emerging, Baron de Vastey’s work which chronicles the abuses of colonialism was not translated in full until 2014. Similarly, the words and thoughts of many throughout history

12 Kant, I. (1802). Physical Geography, [online] Available at: http://www.faculty.umb.edu/lawrence_blum/courses/465_11/readings/Race_and_Enlightenment.pdf

13 Gaffield, J. and Daut, ML. (2018). Haitian Writer Baron de Vastey and Black Atlantic Humanism https://www.aaihs.org/haitian-writer-baron-de-vastey-and-black-atlantic-humanism-an-interview-with-marlenel-daut/

14 Mishra, P. (2017). How Colonial Violence Came Home: the Ugly Truth of the First World War [online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2017/nov/10/how-colonial-violence-came-homethe-ugly-truth-of-the-first-world-war

who fully resisted advances of the colonial world, have never been given the same platform or historical significance as the works of those who continued to perpetuate the master narratives necessary. Such platforms allowed the injustices of colonialism, and the lasting legacy that remains to this day, to avoid its full reckoning.

Seminal Caribbean writer and activist from Martinique, Frantz Fanon brought anti-colonialist perspectives to his work on French occupied Algeria. With blazing detail, he revealed methods of resistance as well as the intricate connections that make capitalism and colonialism intimate bedfellows. In The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon writes “the wealth of the imperial countries is our wealth too…for in a very concrete way Europe has stuffed herself inordinately with the gold and raw materials of the colonial countries: Latin America, China and Africa. From all these continents, under whose eyes Europe today raises up her tower of opulence, there has flowed out for centuries towards that same Europe diamonds and oil, silk and cotton, wood and exotic products. Europe is literally the creation of the Third World” (p 81).15

Works such as this, produced in opposition to imperialist expansion of Europe and the United States, receive little attention or analysis. As Said notes in Culture and Imperialism, “to read Austen, without also reading Fanon…is to disaffiliate modern culture from its engagements and attachments. That is a process that should be reversed.” (p 71). The negation of these (and countless other) voices of objectivity and resistance in the dominant narratives that shape our world, is not incidental but consistent with the idea of erasing, or at least attempting to secure the passivity of, those who fall outside the margins of the categorisations of worth.

To this effect, British historian and hotelier Peter Frankopan writes about this pervasive eradication of the multiplicities of experiences that constitute the history of our world. He details how the imperial conquests which ushered a ‘new dawn’, “propelled Europe to centrestage…its rise however, brought terrible suffering in newly discovered locations. There was a price for the magnificent cathedrals, the glorious art and the rising standards of living that blossomed from the sixteenth century onwards. It was paid by populations living across oceans: Europeans were able not only to explore the world but to dominate it. They did so thanks to the relentless advances in military and naval technology that provided an unassailable advantage over the populations they came into contact with. The age of empire and the rise of the West were built on the capacity to inflict violence on a major scale. The Enlightenment and the Age of Reason, the progression towards democracy, civil liberty and human rights, were not the result of an unseen chain linking back to Athens in antiquity or a natural state of affairs in Europe; they were the fruits of political, military and economic success in faraway continents” (p 202).16,17

15 Fanon, F. (1961). The Wretched of the Earth, France: Francois Maspero editeur

16 Frankopan, P. (2015). The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, London: Bloomsbury

17 We note Frankopan’s rockstar literary status, his extreme wealth, royal European lineage, boutique hotel and grocery store chain and accordingly put forward that this makes for good consideration regarding privilege and

Alongside this ‘new dawn’, sat the capacity to control global narratives and a means to ‘reinvent the past’ (p 219)18. Not only were the rich histories, knowledge, and cultures of others trivialised or erased, but Frankopan writes “history was twisted and manipulated to create an insistent narrative where the rise of the west was not only natural and inevitable but a continuation of what had gone before” (p xix).19

In his analysis Frankopan highlights the excessive levels of competition and warfare which defined the relationship within and between European nations. Noting this history and referencing Enlightenment philosopher Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651), a text often attributed with explaining the rise of the West, in which Hobbes asserts that humans are in a constant state of war, Frankopan writes “only a European author could have concluded that the natural state of man was to be in a constant state of violence; and only a European author would have been right” (p 261).20 Likewise, in Dark Emu Pascoe, commenting on the eightythousand-year history of continual peace in pre-contact Australia, locates war mentality in European consciousness noting that “the idea to pour boiling oil on enemies seems to not have occurred to anyone in Australia.” (p 190)

positioning with respect to dominant narrative. Is it enough to write about injustice instead of taking the path of divesting all ill-gotten privilege, particularly when generating cash by writing about colonialist abuses?

18 Frankopan, P. (2015). The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, London: Bloomsbury

19 Ibid

20 Ibid

The narratives and the modes of knowledge so far privileged in our world, as well as the omissions embedded within them, have compounded to create at least two connected patterns: first, to continue to promote the same principles of hierarchical segregation only in ways that are simultaneously more subversive and more amplified through powerful technologies; and second, to create solutions to increasingly gaping inequities which are either impotent or which contribute to further injustice.

In attempting to understand these patterns, the degree to which our present realities are connected inextricably and inseparable from the iterative and rolling histories which precede us, cannot be understated. To this end, Said writes “there is no just way in which the past can be quarantined from the present”(p. 2)21 However, the inequities which shape our present world, are too often considered without an account of the histories that generated them into

21 Said, E. (1993). Culture and Imperialism, London: Chatto & Windus

being. This creates a collective cognitive dissonance and an inability to address injustices in a systemic manner.

Making a point on the wilful exclusion within academia and in the public sphere, of the impact of imperial rule in shaping modernity not only societies that were colonised, but also the many European nations which have never fully reckoned with their histories, British scholar of Indian origin, Gurminder K. Bhambra writes “sociology’s self-understanding [is] brought about in the European production of modernity as distinct from its colonial entanglements”22 (p 2). This allows for the violence, racialisation and impact of authoritarian power that underpinned imperialism to be overlooked, and for ‘historical injustices [to be excluded] from any consideration of justice in “modern” societies’ (p 145) 23 Understanding the presence of this negation of the realities that shape our histories allows us to more thoroughly decode the narratives and attitudes that shape our present.

The very nature of our globalised world today and the borders drawn around nations, are themselves the legacy of imperial rule, and as explained by Said, “this pattern of dominions or possessions laid the ground-work for what is in effect now a fully global world” (p 4).24

Despite the official dismantling of the British Empire after World War II, not only was the mantle of imperialism passed to the United States who pursued (and continues to pursue) its agenda through militarisation across the world, the lasting legacies normalised through centuries of hierarchical norms and dehumanising practices, stubbornly persist. Further, as Bhambra raises by referencing the work of Siba Grovogui, the director of Africana studies at Cornell University, “even where the processes of decolonization and liberation have transferred political power to the formerly colonized, the institutional, economic, and cultural contexts of Western hegemony have largely remained in place.”

One distorting effect in the present of such an account of the past, has been the sweeping normalisation of the idea of identities that are atomised within national boundaries and defined according to the imposed categorisations of imperialism. Furthermore, segregations and disconnections continue to be made ‘legitimate’ and pervasive through the perpetuation of these narratives by increasingly connected and global superstructures.

In this section, we offer an overview of how persistent hierarchical attitudes embedded within the increasingly powerful and global scientific, technological and economic systems regulate our world. This allows for the further entrenchment and amplification of divisions and arising inequities in ways that are both unprecedentedly consequential and increasingly convoluted in origin.

Key to note for our work in the space of challenging social inequities, is the capacity for such entrenched systems to pervert the course of justice and to skew even our solutions, if arising

22 Bhambra, GK. (2014): Connected Sociologies, London: Bloomsbury Academic

23 Ibid

24 Said, E. (1993). Culture and Imperialism, London: Chatto & Windus

from within the veiled realms from which dominant narratives so often operate. This echoes the work of Bhambra who emphasises the trap of understanding our world through a simple binary of the West as the prototype for modernity upon which all other cultures have framed their own progress, and instead emphasises the importance of realising the “the histories of interconnection that have enabled the world to emerge as a global space” (p 155).25 Claiming a fuller picture of the emergence of our global world and our place in it, allows us to claim stories of ourselves, that if long negated, nonetheless resound within us, waiting to be reexcavated and re-membered into a more complete whole.

In maintaining our belief that the perception of the naturalness or inevitability of global inequities is itself an enabling part of the distorting and skewed historical narratives that shape our present, we here also seek to emphasise the degree to which these narratives are choices, and as such, can be superseded should the collective will and imagination to do so exist. In reformulating such skewed narratives in our world today, we seek to conscientise the necessity of being lucid to, and rejecting, the incomplete histories that taint so much of our identities, and claiming instead a deeper, and more interconnected lens upon which to build our sense of self and our societies.

The impact of the historically sanctioned hierarchies embedded within the narratives that shape our present, continue to be felt within the realm of the bodies of knowledge that today drive our world. Western dominated knowledge such as science, medicine, and economics continue to naturalise the Euro-American conquest narrative in ways that pervasively impact and skew our societies and our global culture.

For example, economists invoke a natural basis for human competition through the Darwinian narrative of survival of the fittest to justify market economies of winners and losers. A fuller engagement with evolutionary theory shows that natural selection is but one of four evolutionary forces at work to create balance on this earth. The only directional evolutionary force, it explains only the origins of species and new traits, not the balanced interactions between all living creatures and the environment. This oversimplification and emphasis on competition not only stops creative problem solving but it justifies reverting to cost as a bottom line. This partial application of one facet of biological theory makes competition seem like an immutable aspect of being human as opposed to the culturally specific worldview that it embodies.

‘Human nature’ predates market economies by at least tens of thousands, if not millions, of years. That human cultural continuity over the course of eighty thousand years on the Australian continent, did not result in a militaristic competitive social framework,

25 Bhambra, GK. (2014): Connected Sociologies, London: Bloomsbury Academic

demonstrates the multiplicity of so-called human natures (Pascoe 2014). As mentioned above, equity, instead of stratification, characterises the 2.5 million-year human archaeological record until five to eight thousand years ago. Likewise, experimental and observational studies of our closest animal relatives, the other primates (with whom we share a 65 million-year evolutionary history) show that humans are also hardwired to be fair and to cooperate. This sort of long view makes it clear that though technological innovation remains characteristically human, inequity is neither our biological nor our cultural baseline.

While some western scientists make the case for an inherently violent and hierarchical human nature (e.g. Wrangham)26 other scholars reveal this as the imposition of internalised thought patterns onto nature. American anthropologist Emily Martin describes this projection and naturalisation in narrative terms. She proposes that purportedly objective scientific writing contains a series of culturally specific “sleeping metaphors” which embody the EuroAmerican master narratives described above. “Waking up” these metaphors “is one way of robbing them of their power to naturalize our social conventions” (p 498).27 When scientists remain blind to the ways that dominant narratives shape aspects of their work, they limit the scope of scientific investigation and the capacity of science to contribute to a balanced and just global order.

Instead, today’s global order rests upon a naturalised narrative of conquest and progress to justify the deep inequities set into motion by imperialism. This progress narrative allowed individuals and individual states to amass vast wealth as they silenced alternative social forms, usurped land and resources through colonisation, committing ethnocide if not genocide, and certainly denying many peoples’ histories, beliefs, and practices in the process. Decoding this narrative as story, instead of biological destiny, allows us to re-member and to re-imagine and construct a different future.

Historical and archaeological evidence combined with cultural practices preserved despite colonialisms’ disruption, demonstrate the human capacity to live in balance with our ecosystems. Pre-contact Australia, for example, was characterised by a “subtle but comprehensive management of the land and its productivity” across the entire continent including its so-called dead heart” (Pascoe p 182).28 Destruction of this productive balanced ecosystem only came about when European colonisers’ practices stripped the land of its fertility as happened with the prairie lands in what is now the United States. Likewise, Amazonian farmers had the knowledge to create richly fertile sustainable soils (Mann 2004) and fisheries (Erikson 2006) without the destruction of the rainforest. Colonisation and land usurpation depended upon constructions of dominant narratives that deny such sophisticated land management. Surfacing known stories about ancient practices will not only restore justice but it will contribute to solving the current environmental crisis.

26 Wrangham, R and Peterson D. (1996). Demonic Males, New York: Houghton Mifflin

27 Martin, E. (1991). The Egg and the Sperm: How Science Has Constructed a Romance Based on Stereotypical Male- Female Roles, Signs,University of Chicago Press, (16)3, (pp. 485-501)

28 Pascoe, B. (2014). Dark Emu, Broome, Western Australia: Magabala Books

Technological innovation and scientific investigation fuel confidence in the progress narrative. We live in a time when fantastical innovations in science and technology allow instantaneous global communication along with rich scientific understanding of many of the physical, chemical and biological mechanisms at work in nature. We also live in a time of fragmentation during which the power of data to reveal truths a fundamental aspect of scientific investigation has diminished. A focus on increasingly massive data sets and machine learning to seek truth from these data, limits the kinds of discoveries possible through science while also amplifying the capital required to conduct research.

Spectacular in their capacity to produce, technological innovation and scientific research take place within market economies. Ultimately, these same markets limit access to the new bounty that innovations generate such that, all too often, the fruits of scientific investigation become mired in discussions about the unequal distribution of scarce resources. Likewise, potential profits define which paths of innovation get explored limiting our collective creativity.

Resulting innovations tend to seed divisions and disenfranchisement without addressing true root causes of inequity. Poverty alleviation models focus on closing the gap so that all peoples can receive the bounty without considering that the current market driven way of life is wholly unsustainable and fundamentally flawed. These various forms of disenfranchisement have led to polarisation, anger, and othering all of which stand in the way of finding our shared humanity, our hidden histories and our deep connection to the natural world. Narrative opens paths for re-connection.

Some might argue that science itself remains pure and free of pernicious market forces while simultaneously reaching across the globe. The truth is more complicated. The dominant narrative has naturalised an accelerating path of innovation harnessing discoveries designed to control and bend natural phenomena to serve human needs. While acknowledging the powerful capacities of scientific investigation and the noble dedication of so many health workers, we argue instead that science and medicine have become big business. As a result, they can sometimes serve to perpetuate the status quo while diminishing their generative capacity for both discovery and health.

This begs the question: what exactly can science discover? Science discovers mechanisms and ways things work. It neither engages with questions of why things happen nor of their meaning, just with how. With a world in a standstill to cope with COVID-19, with seasonal wildfires raging annually on at least two continents, ice caps melting, and rising sea levels infringing on coastal cities, this human manipulation of the environment has progressed well beyond the boundaries of sustainability. While ethical engaged scientists have marshalled evidence of this human made destruction, many individuals, corporations, and even governments choose to ignore these data. Further, scientists remain shackled by the dominant paradigms in their search for solutions. For example, this moment’s earnest search for a COVID-19 vaccine will solve only today’s most proximal immediate problem. Ultimate

solutions require shifts at the deepest structural levels at work in our world. This is the place of narrative.

Further, in its most authentic form, science can be seen as a quest for knowledge whose horizons continually shift: We are limited in our understanding of the world by knowledge we are yet to gain. Science is never complete, but always in pursuit. Instead, often pitted in opposition to story, to magic, to mystery, science becomes aligned fully with a ‘rational’ worldview and the progress narrative. The power of science and technology renders beliefs and practices of cultural frameworks with origins distinct from those of the progress narrative somehow as lesser. We argue that our very survival requires engaging with questions of meaning that lie at the heart of narrative. It requires broadening a definition of science that is trapped within the dominant narratives of the Eurocentric ‘progress’ narrative and embracing all forms of Indigenous and cultural sciences - many of which have long effectively grappled with questions of environmental sustainability, wellbeing and ecosystem balance. This requires looking outside of today’s dominant paradigms for solutions. Restoring balance and creating fairer, healthier, more equitable societies demands rebooting and redefining our deepest social structures including those that tie technological and scientific innovation to hierarchical market economies.

One of the most pernicious impacts of a centuries-long history of the creation of nation states and on the categorisation of people based on skin colour, race and creed, has been a resounding normalisation of an understanding of our identities that arise from within the confines set by these boundaries. This internalisation of a view of identity that rests on externalities and superficialities, threatens to diminish our ability to imagine into being a world based on the fullness and the interconnectedness of the human story. On precisely this matter, in Culture and Imperialism Said writes “no one today is purely one thing. Labels like Indian, or woman, or Muslim, or American are not more than starting-points, which if followed into actual experience for only a moment are quickly left behind. Imperialism consolidated the mixture of cultures and identities on a global scale. But its worst and most paradoxical gift was to allow people to believe that they were only, mainly, exclusively, white, or Black, or Western, or Oriental. Yet just as human beings make their own history, they also make their cultures and ethnic identities. No one can deny the persisting continuities of long traditions, sustained habitations, national languages, and cultural geographies, but there seems no reason except fear and prejudice to keep insisting on their separation and distinctiveness, as if that was all human life was about” (p 336).

In the same vein, in his book Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon writes with respect to the European colonisation of Madagascar, “a Malagasy is a Malagasy; or rather he is not a Malagasy, but he lives his ‘Malagasyhood’. If he is a Malagasy it is because of the white

man” (p 78).29 Fanon’s point is to demonstrate that identity becomes set in relation to ‘the other’ that is, being Malagasy, or black or brown, is established as a comparison to whiteness. Without being pegged against a standard of ‘the other’, that itself is never racialised, these identities do not exist in the same way. Similarly, he writes “inferiorisation is the native correlative to the European’s feeling of superiority. Let us have the courage to say: it is the racist who creates the inferiorised” (p 73).30 Fanon is amongst the first to highlight the psychological impacts of imperialism, and in his work he raises the danger of the internalisation of the ideologies of imperialism by colonised people. The adoption of these ideologies can result in the acceptance of inferiority and the emulation of the actions of oppressors.

Introducing the notion of ‘cultural imposition’, Fanon explains the distorting force of the weight of socially driven norms upon the individual identities of those who are largely oppressed and repressed by these collective norms. Underpinning ‘cultural imposition’, is Fanon’s central idea that our identities as individuals are created in relation to, and filtered through, society as a collective. The shared collective unconscious of a society at any given time, Fanon argues, is not derived from internally encoded instinct (as other prominent psychoanalysts like the Swiss Carl Jung argued at the time), but is acquired, and is “quite simply the repository of prejudices, myths and collective attitudes of a particular group” (p 164).31 In a world shaped by the dehumanising categorisations of colonialism, Fanon argues that this renders those who have been the object of repression and rejection amenable to cultural imposition, “a black man who has lived in France, breathed in and ingested the myths and prejudices of a racist Europe and assimilated its collective unconscious can, if he splits his personality, but assert his hatred of the black man” (p 165).32

It should be stated that given the deeply entrenched physical and psychological manifestations of identities that have long been shaped by divisive systems of power, it is not always a straightforward task to generate solutions to injustice which can ameliorate this historical impact. Similarly, Bhambra makes the point that “it is not so easy to overcome the institutionalised hierarchies of five hundred years of systematised discrimination on a global scale. Independence does not equate to justice, nor emancipation to equality.”33

In spite of the difficulties (and perhaps, because of them) we suggest that a critical part of claiming our true transformative potential, involves rejecting the narrowed vision of identity from which we are so often expected to operate. Instead, we may reach beyond these stilted and narrowed frames, to claim ourselves within the deepened and broadened frame which arises by recognising the connected histories which shape us.

29 Fanon, F. (1952) Black Skin, White Masks, Paris: Editions du Seuil

30 Ibid

31 Ibid

32 Ibid

33 Dawes, S. and Bhambra, GK. (2011) Interview with Gurminder Bhambra on Colonialism, Empire and Slavery, [online] Available at: https://theoryculturesociety.org/interview-with-gurminder-bhambra-on-colonialism-empire-and-slavery/

To understand this further, it is perhaps useful to assess examples of how identities of individuals, groups of people, and entire regions have been manoeuvred to accept the false and distorting narratives which arise from unreckoned and systemised histories of injustice.

The contemporary attitudes to sexuality in many previously colonised regions, are far more rigid and discriminatory today, than before colonisation, offering a stark example of the sustained disruptive impact of imposed historical narratives. The attitude towards sexuality normalised by Enlightenment and religious thinkers, was one which contributed further to the capacity to categorise and control those in the regions being colonised globally. Many African, Pacific Island and Indigenous people who were met by European colonisers had greater fluidity around the notion of sexuality than that which was present in Europe at the time. This was used to confirm the ideas of “native promiscuity” and to hyper-sexualise nonEuropean men and women, justifying the need for religiously inspired cleansing, with legacies whose impact continues till this day. Journalist and organiser Layla-Roxanne Hill writes “the regulation of women and/or sexuality in non-Western countries can be traced back to colonial legacies rooted in penal codes…In 1885, the British government introduced new penal codes that punished all homosexual behaviour. Of the more than 70 countries that criminalise homosexual acts today, over half are former British colonies.”34 Furthermore, the rules around marriage and the legitimacy of children which were introduced across colonised states, were closely related to property rights and to further enriching slave owners by allowing them to own the children of enslaved mothers.35

Such discriminatory attitudes towards sex and sexuality persist in ways that are now so deeply held and pervasive that they have come to scramble contemporary notions, and twist memories, of the matter across many previously colonised nations. Black British writer and activist Bernadine Evaristo writes about the myth now internalised across the African continent, of a “pre-colonial sexual innocence”, which maintains that homosexuality did not exist until white men imported it. This myth is used by political leaders across the continent to stir homophobia in order to increase their own popularity and power. Evaristo writes that, counter to this myth, “from the 16th century onwards, homosexuality has been recorded in Africa by European missionaries, adventurers and officials who used it to reinforce ideas of African societies in need of Christian cleansing…The truth is that, like everywhere else, African people have expressed a wide range of sexualities. Far from bringing homosexuality with them, Christian and Islamic forces fought to eradicate it. By challenging the continent's indigenous social and religious systems, they helped demonise and persecute homosexuality in Africa, paving the way for the taboos that prevail today.”36

34 Hill, L. (2019) Let’s Talk about Sex (and Race and Colonialism) [online] Bella Calledonia. Available at: https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2019/06/09/lets-talk-about-sex-and-race-and-colonialism/

35 Turner, S. (2018) Sexuality, History, and Britain’s Colonial Legacy [online] Black Perspectives. Available at: https://www.aaihs.org/sexuality-history-and-britains-colonial-legacy/

36 Evaristo, B. (2014) The idea that African homosexuality was a colonial import is a myth [online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/mar/08/african-homosexuality-colonial-import-myth

Yet another example of the further contribution towards injustice on questions of identity generated by unreconciled histories, is how we perceive migrants and refugees in our world today. The number of displaced people in the world sits at unprecedented levels, with the UN reporting over 70 million people have left their homes, many of them forcibly. The reception that such refugees have met across the world at its worst, has been one of hostility and exclusion, with their plight used to justify the increasingly nationalistic rhetoric of demagogic leaders across the globe. At best, the argument forwarded by those who would seek a more sympathetic approach to migrants/refugees is laced with language of economic contributions or magnanimous notions of morality. However, if we move the narrative beyond the frame set by incomplete accounts of history and into the reality of the connections that link global stories together the international responsibility for having created displacement becomes clear.

The unreconciled histories underpinning the narrative around migrants/refugees, makes it possible to continue to categorise these predominantly black and brown refugees in the same manner perpetrated by historical colonial projects. On this matter Bhambra writes that the distinction between migrants/refugees on the one hand and citizens on the other, is based on a false distinction normalised by incomplete versions of history. The ability to exclude swathes of people from a right to a safe and dignified life, is justified by at least two myths: first, the widespread negation of the fact that European wealth and relatively high standards of living have been built upon the labour and wealth of others, thereby absolving richer countries of their complicity in generating refugees to begin with; and second, by internalising the very ideas of exclusionary identity and nationhood that are necessary in order for European power to remain undisturbed. Bhambra writes “our distinction between migrants/refugees on one hand and citizens on the other is based on a false version of history, one that draws a distinction between states and colonies whose histories are, in fact, inextricably entwined. We have to understand the contemporary crisis in the context of these connected histories, and to think of the histories of states and colonies as one and the same. The failure to properly account for Europe’s colonial past cements the political division between legitimate citizens with rights and migrants/refugees without rights as members of the political community.”37

Re-framing the narrative surrounding migrants/refugees in this way positions us to see that our histories are inseparable, and our identities far more connected than the narratives in our present world would have us conclude. The implications of this shift would lend itself to the generation of an entirely different premise from which our obligations and notions of justice towards those who are displaced arise. It would even lead to a different conscientisation of the factors that contribute to the creation of refugees and displaced people in the first place.

37 Bhambra, GK. (2015) Europe won’t resolve the ‘migrant crisis’ until it faces its own past, [online] The Conversation, Available at: https://theconversation.com/europe-wont-resolve-the-migrant-crisis-until-it-faces-its-own-past-46555

Almost six decades ago, in his book The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon wrote “what counts today, the question which is looming on the horizon, is the need for a redistribution of wealth. Humanity must reply to this question, or be shaken to pieces by it.”38 Today, we are witnessing this convulsion of not having adequately reckoned with the question of the equitable distribution of wealth.

Infused through the global, and hugely stratified, world that we now inhabit, sits a dominant ideology which French economist Thomas Piketty describes in his book Capital and Ideology as “neo-proprietarianism”39 a worship of private property rights above all else. This modern ideology, argues Piketty, has normalised policies which drive tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy, often in opaque and hidden ways. Simultaneously, the economic burden of these cuts is transferred onto households driving the gaping wealth inequalities which define our era.

Piketty argues that such realities are not natural or predefined outcomes driven by capitalism. Instead, political and ideological choices drive this reality. In fact, Piketty’s main thesis is that all inequality depends entirely on the chosen ideology on narratives.

Many of these choices of the deep hierarchies of worth, and the structural and systemic inequities which have generated climate crises and the disproportionately non-Western profile of those who have been most affected find their genus in the very same narratives of segregation and racialisation that define our recent world history. Noting the same inseparability as raised by Said between skewed power structures and the creation of nationalist identities, Piketty concludes that the “only way to transcend capitalism and ownership society is to work out some way of transcending the nation-state”. Piketty espouses an ultimate view of the inevitable failure of schemes and systems underpinned by such gross inequity, citing that historically, all mass inequity does not remain sustained.

This problem of extreme wealth inequity driven by global systems of capitalism, sits alongside the increased capacity of technology for amplified mass surveillance. In her book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, US scholar and writer Shoshana Zuboff argues that a new type of capitalism has taken hold. If in the industrial capitalism of the past, nature’s raw materials were transformed into commodities, in today’s digital age, we ourselves are claimed as the raw materials. Zuboff explains “surveillance capitalism unilaterally claims the human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioural data” (p 8) 40

38 Fanon, F. (1961). The Wretched of the Earth, France: Francois Maspero editeur

39 Piketty, T. (2020). Capital and Ideology, Belknap Press

40 Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, PublicAffairs

With surveillance capitalism, comes the dire capacity to entrench already resounding notions of hierarchy and exclusion in ways that are amplified and untraceable, through the power of algorithms and technology. The sheer scale of information transmitted from users to datadriven companies like Google, allows for the generation of a repository of data from which predictive behavioural analysis can be gleaned. Zuboff emphasises that the threat to the notion of equity arises because surveillance capitalism not only transgresses our privacy, but, disturbingly, it aims to control our behaviour for political gain and commercial profit. It decisively erodes any semblance of the idea of free choice on the market, and even our free will

In such an age, the Foucauldian knowledge-power cycle (and Doxtater’s colonial-knowledgepower cycle) takes on unprecedented significance the centralisation of disproportionate masses of knowledge into the control of a mere handful of companies. It also transfers power in ways that are severely disfiguring to the notion of equity. These power houses operate from behind a veil of secrecy. Zuboff notes that “theirs was an invisibility cloak woven in equal measure to the rhetoric of the empowering web, the ability to move swiftly, the confidence of vast revenue streams and the wild, undefended nature of the territory they would conquer and claim” (p 10).41

Importantly, Zuboff reminds us that “surveillance capitalism is not an accident of overzealous technologists, but rather a rogue capitalism that learned to cunningly exploit its historical conditions to ensure and defend its success” (p 17) Commercial surveillance is, Zuboff writes, “a specifically constructed human choice” (p 91).42 Again, we are reminded of the fallacy of the inevitability of such grossly skewed landscapes of inequity, with Zuboff ultimately determining such an overly-ordered, predictive reality to be a ‘utopia’ destined for failure.

Disconcertingly, caught in the web of the intersecting strands of the persistent hierarchies of categorisation of human worth and the acute centralisation of power that wrap around our world, even many of the narratives that underpin our solutions are tainted and trapped.

An example of a pervasive way this plays out today is raised by Indian American writer Anand Giridharadas, in his book Winner Takes All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World. Giridharadas critiques the ironic contemporary solution offered to so many of our global ails: the creation of ‘solutions’ to poverty driven problems by the world’s billionaires. Those creating the problem determine what constitutes social justice.

41

42

Giridharadas notes “all around us in America is the clank-clank-clank of the new in our companies and economy, our neighbourhoods and schools, our technologies and social fabric. But these novelties have failed to translate into broadly shared progress and the betterment of our overall civilisation (p 1).”43 Instead, all benefits and gains have been siphoned upwards, “such that the fortunes of the world’s billionaires now grow at more than double the pace of everyone else’s, and the top 10 percent of humanity have come to hold 90 percent of the planet’s wealth” (p 5).44 Giridharadas notes that, in response, voting publics around the world have, alongside becoming more susceptible to embracing fake news and populist movements, developed a growing anger and suspicion about the effectiveness of the systems that regulate our lives.

Faced with this rising tide, elites around the world have both barricaded themselves away on private estates emerging only to take more political power or to defend themselves. Recently, many have also taken ownership of the problems their funnelled wealth has created and declared themselves the partisans of change. While some may support ordinary people who are already working amongst their communities to generate social change, “more often, these elites start initiatives of their own, taking on social change as though it were just another stock in their portfolio…Because they are in charge of these attempts at social change, the attempts naturally reflect their biases” (p 5).45 Critically, these initiatives are often based on bypassing public regulation, and look to the market to solve problems.

Though the elite of today may be more socially minded, Giridharadas makes the point that many of these initiatives are designed to supplement the fact that the powerful do not want to sacrifice for the common good. Accordingly, they have developed a set of arrangements that monopolises the benefits of innovation and progress, while “giving scraps to the forsaken many of whom wouldn’t need the scraps if the society were working right” (p 7).46

Giridharadas makes the point that the singular act of multinational corporations and billionaires not evading their tax responsibilities would be more useful in allowing people to live dignified lives, than their setting up of philanthropic organisations made in their own image. Ultimately, these half-measures prevent real systemic change, and not only fail to allow things to evolve, but keeps them in a state of stasis. It boils down to whether elected and accountable governments or by wealthy elites claiming to have society’s best interests at heart lead the reform of our public lives. Giridharadas posits that even though today’s systems of democracy are failing in many ways, it generates even deeper problems to attempt to sideline democracy rather than work to improve it.

Evidence of a world driven by wealthy elites, already resounds. With so many of the world’s ultra-elite dependent on global business models with high carbon footprints, we are seeing anaemic responses (both corporate and political) to even some of the greatest challenges of our time climate change, and more recently, to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the United

43 Giridharadas, A. (2019). Winner Takes All: the Elite Charade of Changing the World, Penguin Books

44 Ibid

45 Ibid

46 Ibid

States, world renowned linguist and dissident Noam Chomsky states in a July 2020 interview with Democracy Now!47, that the United States is “a country run by the corporate sector which has overwhelming influence on the government…symbolised by the richest man in the world, Jeff Bezos, who made $13 billion in a single day…They’re using the cover of the pandemic to increase their dedication to enriching the very rich and the corporate sector”.

During the Trump era, Chomsky explains, “the corporate figures that have been placed in charge of agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency, pass further legislation to smash the public in the face and enrich the rich, like cutting back pollution standards”.

This corporate driven response to the climate crisis follows a pattern across developed nations around the globe. In Australia, even at the height of the unprecedented bushfire season of summer of 2019/2020, both major political parties were reluctant to acknowledge the impact of climate change or commit to serious policy changes. Novelist and commentator Richard Flanagan writes, “incredibly, the response of Australia’s leaders to this unprecedented national crisis has been not to defend their country but to defend the fossil fuel industry, a big donor to both major parties as if they were willing the country to its doom. While the fires were exploding in mid-December, the leader of the opposition Labor Party went on a tour of coal mining communities expressing his unequivocal support for coal exports. The prime minister, the conservative Scott Morrison, went on vacation to Hawaii.”48

Noting the potential for the further trapping of solutions to global problems in favour of the elite during a time of pandemic, Indian writer and activist, Arundhati Roy considers the pandemic a portal to the world that is next coming. In an April 2020 interview, Roy states “right now what’s happening is that national authoritarianism is colluding with international disaster capital and data gatherers and they are preparing another world for us…if corporate globalisation was advanced capitalism, now they would like us to move into an even more advanced version of that, where you have the Gates foundation more or less owning the World Health Organisation, deciding public policy and how to make massive profits out of whatever protocol is going to be rolled out to deal with this epidemic. And that would involve data gathering and surveillance. If we were sleepwalking into a surveillance state, now we are panic running into it, because of a fear that is being cultivated within us.”49

In a few brief final examples amongst many, of ‘solutions’ which exacerbate problems, we include a feminism driven by a Western ideology of liberation (itself heavily tainted by imperialism and capitalism) that is transposed authoritatively onto women of colour. Labelled as ‘imperial feminism’ by British filmmaker of Indian origin Pratibha Parmar, because it posits that “other” women need saving by white women to attain this white version of liberation thus denying diverse forms of female agency and power. In the same vein, the

47 Chomsky, N. (2020) Trump Is Using Pandemic to Enrich Billionaires as Millions Lose Work & Face Eviction, [online] Available at: https://www.democracynow.org/2020/7/24/noam_chomsky_trump_is_using_pandemic

48 Flanagan, R. (2020) Australia is Committing Climate Suicide, NY Times [online] Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/03/opinion/australia-fires-climate-change.html

49 Roy, A. (2020) The Pandemic is a Portal, Haymarket Books [online] Available at: https://www.haymarketbooks.org/blogs/130-arundhati-roy-the-pandemic-is-a-portal

declaration of the war on terror in Afghanistan in 2001, was morally supported by the declaration by then President Bush that “today, women [in Afghanistan] are liberated”. Almost two decades later, countless (and uncounted) dead, and incessantly precarious conditions for all those in Afghanistan, this ruse of feminism enforced by military might and imperial occupation has unleashed only travesty.

And perhaps one of the greatest trapped solutions of our time is the Internet and associated digital technologies. Once heralded as a great democratic equaliser, the Internet is now an oligopoly tightly held by giant corporations like Google, Amazon and Facebook. Through their business models advocating sensationalist click bait, predictive behavioural analysis and monopolised advertising revenues these corporations have had far reaching and diminished implications for systems of democracy, and for diversity in news, politics and opinion. Similarly, the algorithms underpinning artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning that are synonymous with today’s narratives of progress continue to build in and amplify human biases. These algorithms (increasingly the measure being used to determine the outcome of significant issues such as mortgage approvals, job prospects, criminal prosecutions and policing tactics) have already been shown to build in significant racial and gender bias. One recent study showed that an IBM AI trained to recognise gender, could recognise with 99 percent accuracy the faces of white men, and plummeted to 35 per cent accuracy when faced with dark-skinned females.50 Such technologies require serious corrections and ethics-based scrutiny, as they pose an amplified threat to the question of justice and for the increased fortification of racial and gender driven biases.

50 Cossins, D. (2018) Discriminating algorithms: 5 times AI showed prejudice New Scientist [online] Available at: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2166207-discriminating-algorithms-5-times-ai-showed-prejudice/

“I imagine a world in which, if capitalism must exist, there is a safety net for everyone who lives under its umbrella, so that the most vulnerable are actually not that vulnerable because everyone has their basic needs met: suitable food, shelter, health care.

I imagine a post-COVID world in which our institutions for global good, the United Nations among them, are revitalized and valorized because of the critical work that they do to craft a global vision and a global strategy to address global issues. Where a global vision becomes as important as a local one.

I imagine a post-COVID world in which people after receiving much needed human interactions with one another; after braving possible exposure to the coronavirus in order to give care to others; and after recovering from managing remote-learning while also carrying out their own work go on to better cherish shared public spaces and institutions and community with renewed vigour so that we're able to build stronger commitments for the greater good.

In other words, we make actionable the lessons that we have learned.”

Cedric Brown AFRE FellowJust as the power of narratives has been systematically harnessed to generate norms that fracture our relationship to ourselves, one another, and the natural universe so too can they be used to re-member, to shift the tide of history towards the shores of justice and universal humanity.

Many within and beyond the Atlantic community already have begun to explore the capacity of narrative to address injustice. We believe that there is still much to conscientise around how narratives can be harnessed to realise our human potential. This includes unravelling how narratives that have been used to create a fractured world, how they may have filtered through into the work we carry out, and often seep into the identities we internalise as our own. Conscientising these hidden yet dominant narratives lets us reckon with their impact, liberate ourselves from their bind, and redirect the power of narratives to heal.

Here, we assess some of the ways that narratives are being used as a tool for social change so far, to build up to some recommendations for further developing the power of narratives as a means for re-membering and re-imagining what is possible in our world.

Atlantic is not alone in recognising the place of narrative in social change. Increasingly social change makers turn to narrative, tapping into our deepest human capacity to make sense of