An Atlantic Institute Report

Dr. Wilneida Negrón

Dr. Wilneida Negrón

Dr. Wilneida Negrón is a 2019 Global Atlantic Fellow for Racial Equity. An Atlantic Institute Leader-in-Residence (2022-2023), she focused on new models of leadership for global changemakers. She began her career as a therapist and social worker in the juvenile justice system, and now devotes her life to exploring new ways of bridging across differences, beliefs, disciplines, issue areas and sectors. She also works with communities, workers, policymakers and the private sector on innovating new programs, processes and institutions that can uphold human dignity and agency in the innovation economy. She has a Ph.D. in comparative politics, a master’s degree in international relations and a master’s degree in public administration.

Copyright 2023

Introduction

Chapter 1: Toward a New Leadership Trajectory

Chapter 2: A Global Network of Changemakers

Chapter 3: Uniquely Global, Multidisciplinary and Equity-Focused Community

Chapter 4: Introduction to the Pressure Point Mapping Framework

Chapter 5: Looking Into the Fast-Approaching Future

Appendix 1: Survey/Interview Tool

Leadership development pedagogy often focuses on skills or professional development, omitting something essential — our shared humanity — even in organizations committed to the ideal that every human needs to be seen, heard and given the opportunity to live a life of hope, freedom and equity. Valuing our universal human experience is particularly important in an increasingly complex world where much of our day-to-day existence and interaction is mediated through technology. Factoring the human experience into support of leaders could unleash greater capacity for continued adaptation, variation and ingenuity. Despite persistent structural challenges and rapid technological change, this report describes the skills we need most in order to authentically find, see and support each other toward the goal of social change and transformation.

The challenges of deeply structural and systemic inequities (e.g., socioeconomic, health), racism and anti-blackness are not only increasing in urgency, but also becoming increasingly complex in an era of political and socio economic instability and technological change. These challenges may appear to be intractable and insurmountable, but we can overcome them if we adopt new ways of being and work together across fields, disciplines, issues, regions and strategies.

The challenges and the opportunities can be seen in the stories of changemakers: individuals taking action to solve problems in their communities and/or the world at large. Around the world, aspiring changemakers embark on what is often a long and solitary journey to realize their potential and undertake action to challenge and/or resolve a problem. The journey from that self-actualization to action puts them in direct contact with deeply entrenched systems, structures and processes — and also with the realities and vulnerabilities inherent in people’s lives. With them on these journeys, are changemakers’ own inherent beauty, individuality, complexity and imperfections.

Changemakers sometimes traverse systematized pathways and trajectories to bring about social change. While few changemakers receive recognition or support for their efforts, some do. A small percentage are invited or selected to participate in exclusive professional and leadership development programs that include fellowships, awards or residencies and may increase the odds of success for other grant opportunities — much like the Global Atlantic Fellows community. In addition to providing opportunities for collaboration and networking, these professional spaces also support changemakers and help to sustain their work.

It is also in these spaces that every day changemakers encounter the language and pedagogy of leadership. Prescriptive efforts are offered as a service to changemakers, intended to deepen the analytical and impact tools of changemakers to help amplify and deepen their impact. Yet in my conversations with more than seven dozen changemakers worldwide who are part of the Global Atlantic Fellows community, most rejected (to varying degrees) the language and pedagogy of leadership frameworks and theories that are so often imposed on them. Instead, based on journeys both imperfect and unexpected, many of these Global Atlantic Fellows expressed a real hunger to deconstruct professional facades and embrace the personal, relational and social transformations

that embody so much of the daily life of a changemaker, along with the juggling of hopes, dreams and fears.

What I heard, in essence, was the desire to be seen more as fellow humans than as leaders. A similar sentiment surfaced in “The Catalyst’s Way,” a report by Chellie Spiller, a New Zealand professor at the University of Waikato Management School, who wrote of her experience in interviewing changemakers for the Atlantic Institute:

“Leadership in this space is a tricky, complicated term. Many catalysts see themselves as contributors, facilitators and collaborators — not as ‘leaders.’ They especially resist notions of leaders as exceptional with positional, hierarchical and authoritative privileges and reject command and control approaches.”1

My conclusion on how to best support changemakers is to first center their humanity. Doing so centers the complexity of the human experience of being a changemaker. It also increases the transparency of the challenges associated with juggling the personal, professional, moral, and ethical challenges and struggles of most changemakers. By centering Fellows in their full life journey, adult learning theory demonstrates how this can enable a greater exploration of the multiplicity of experiences, ideas, approaches, solutions as well as greater reflective and adaptive practices toward shared goals.

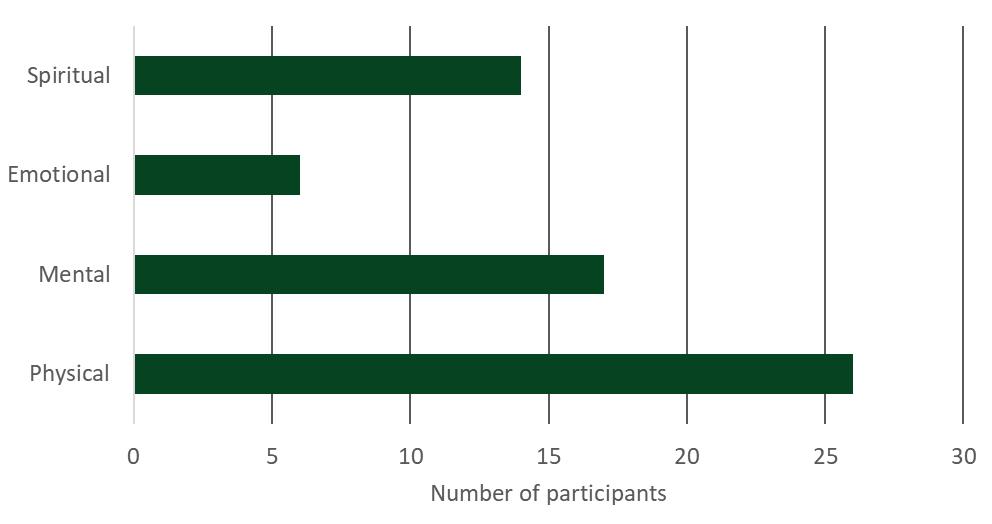

This conclusion is based on surveys and interviews with 85 Global Atlantic Fellows following completion of one of the seven Atlantic Fellows programs and their ongoing work as members of a lifelong community. From these interviews, navigating complexity was the most dominant theme. The types of complexity discussed include leadership and organizational/systemic complexity, with an emphasis on physical and emotional demands. Meanwhile, their leadership work calls on them to continue focusing on dominant physical and mental traits. This is despite the fact that the more emotional- and interpersonal-driven characteristics are actually what most Global Atlantic Fellows admire in other leaders and themselves.

The latter insight emerges from my analysis of these survey/interview responses and draws on some of the findings of Spiller’s report. This paper presents a framework for identifying central intersectional pressure points (e.g., personal, relational and social transformations) that many changemakers grapple with on their journeys. This tool and my analysis can help guide changemaker support and community-building efforts.

Each chapter of the report begins with a short, mostly fictional account that is a mix of stories, ideas and quotes from the surveys and interviews. I chose this approach of storytelling across regions, issue areas, fellowship programs and strategies for several reasons. First, I wanted to complement the work of the storytellers featured in the “The Catalyst Way” report by identifying and highlighting some universal themes in fictional storytelling prose. Second, given that topics of discomfort and tension often surfaced, I wanted to ensure confidentiality to the Fellows who participated in the survey/interviews. Third, while every fellowship program is unique (e.g., in recruitment, leadership development training and pedagogy and the experiences and support offered), the aim was to understand the Global Atlantic Fellows community as a whole and explore areas of commonality. Finally, throughout the report, the term “changemakers” is interchangeable with Global Atlantic Fellows.

1 Chellie Spiller, “The Catalyst’s Way,” 4.

We have much to gain by embracing the messy and imperfect work of being changemakers. While some areas of work can be tracked and measured in leadership programs focusing on determining impact, others call for a shift in focus to the individual and navigating life. First, helping changemakers turn inward, as opposed to constantly being consumed by professional demands of external representations of self and work, we can help changemakers develop the skill of maintaining stillness and silence,2 which helps to sustain their work. Second, centering conversations and experiences around life challenges, struggles as well as hopes and dreams can help changemakers enter collaborative and networking spaces from a place of situational humility and curiosity. These two factors are essential for creating a psychological sense of safety that enables risk-taking with strangers,3 and can lead to building bridges (e.g., across fields, equity frameworks, disciplines, issues, regions and strategies) to address the critical problems of our time.

2 C. Spiller et al., “What Silence Can Teach Us About Race and Leadership,” Leadership 17, no. 1 (2021): 81–98, https://doi. org/10.1177/1742715020976003.

3 A. C. Edmondson, “How to Turn a Group of Strangers Into a Team,” Ted Talk, 2017.

He began his career as a banker in Atlanta, Georgia, and worked for large corporations. In response to seeing protests over the Dakota Access pipeline and meeting Navajo and Puebloan members during a business trip to Arizona, he became interested in learning more about the historical struggles and culture of these communities. Although he was born in the U.S., he was embarrassed that he actually knew very little about the Native American communities that play an important role in that history. On family visits later that year to several reservations in the Southwest, he found himself increasingly engrossed in their culture and stories. As a result of this experience, he grew increasingly appreciative of the rich and complex heritage of the United States. This trip was a major catalyst and he later packed up his car and traveled all over the country, connecting with a number of Native communities that deeply touched him and planted the seed that culminated a decade later. Although he had never been involved in activism or social justice work before, he wanted to see if he could put his business skills to work to advance justice and equity for these communities.

Leadership studies have provided detailed insights into the traits, values and characteristics of effective leaders. There also are a growing number of books, training programs and pedagogies devoted to teaching leadership attributes and practices to adults and children. Despite the advances of these studies from both a human development and cross-sectoral perspective (e.g., helping foster more effective leaders in management, business and social justice), the field is not without criticism. Among them is the belief that leadership studies are heavily influenced by Western thought, views and culture and are overly biased toward masculine, individualistic and heroic traits. As a result, non-Western groups feel that focusing on the individual is not helpful for understanding more collective forms of leadership. In the case of the Global Atlantic Fellows, this bias can leave little room to explore the kinds of collective organizing models required for facilitating social transformation at a societal or global level, or work where common purpose is distributed across several initiatives that have to be bridged, translated, coordinated and aligned.

Furthermore, growing evidence suggests that leadership studies do not adequately prepare leaders for navigating complexity.4 Some studies have argued that leadership should be less personality-driven and more fluid, adaptive5 and this includes being able to incorporate a mix of styles and leadership practices,6 including top-down and/or relational, distributed and collective approaches7 in response to different contexts. To this end, these more adaptive and reflexive

4 M. Uhl-Bien, “Complexity Leadership and Followership: Changed Leadership in a Changed World,” Journal of Change Management: Reframing Leadership and Organizational Practice 21, no. 2 (2021): 146–162, DOI: 10.1080/14697017.2021.1917490

5 Uhl-Bien, “Complexity Leadership and Followership.”

6 In the article, “From Leadership-as-Practice to Leaderful Practice,” J. Raelin defines leadership-as-practice as “how leadership emerges as a practice rather than residing in the traits, character or behaviors of individuals — in which traditional approaches to the study of leadership place emphasis.”

7 Viviane Sergi et al., “Saying What You Do and Doing What You Say: The Performative Dynamics of Lean Management The-

practices have been found to help facilitate the collaboration, adaptation and resilience8 needed to navigate complexity. Resilience — a skill several Atlantic Fellows programs note is important — is found to be produced by the interplay of cognitive and behavioral shifts,9 or internal disposition in responding to external experiences and events.10 Therefore, it is essential to develop and deepen these capacities for both reflection and action in the face of complex challenges, but also for strengthening the skill and practice of resilience.11

Two additional branches of leadership studies — social justice and racial equity leadership — complement this analysis on the role of critical reflection and adaptive and reflexive responses. Social justice leadership also takes a more holistic approach to understanding leaders through its identification of several dimensions critical to the praxis of this particular type of leadership: the interconnections between the personal, interpersonal, communal, systemic and ecological.12 In racial equity leadership, studies highlight the importance of leadership being the enactment of values.13 According to these studies, leadership development programs should help leaders develop approaches that enable them to challenge their own assumptions, clarify and strengthen their own values and work on aligning their own behaviors and practice with these beliefs, attitudes and philosophies.

To get insights into how to foster these capacities in an adult learning context, the body of work on transformative learning provides useful insights. Transformative learning focuses on how adult learners make sense or meaning of their experiences, the nature of the structures that influence the way they construct experience,14 the dynamics involved in modifying meanings and the way the structures of meanings themselves undergo changes when learners find them to be no longer helpful.15 Additionally, like studies looking at how leaders can better adapt to complexity, transformative learning also emphasizes focusing on the centrality of experience, critical reflection and rational discourse.16

Some relevant pedagogical strategies include:

• Completing cultural autobiographies.17

• Engaging in life history interviews.

• Writing in reflective analysis journals.

• Engaging in self-directed, experiential learning.18

ory,” Department of Management, Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia Working Paper No. 35/2013, December 2013, https://ssrn.com/abstract=2374287.

8 Lucia Crevani et al., “Changing Leadership in Changing Times II,” Journal of Change Management 21, no. 2 (2021): 133–143, DOI: 10.1080/14697017.2021.1917489.

9 A. Pangallo et al., “Resilience Through the Lens of Interactionism: A Systematic Review,” Psychological Assessment 27 (2014): 1–20, doi: 10.1037/pas0000024.

10 R. Dias et al., “Resilience of Caregivers of People with Dementia: A Systematic Review of Biological and Psychosocial Determinants,” Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy 37 (2015):12–19, doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2014-0032.

11 Dias et al., “Resilience of Caregivers of People with Dementia.”

12 G. Furman, “Social Justice Leadership as Praxis: Developing Capacities Through Preparation Programs,” Educational Administration Quarterly 48, no. 2 (2012): 191–229, https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X11427394.

13 L. Miron, Resisting Discrimination: Affirmative Strategies for Principals and Teachers (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 1996).

14 J. Mezirow, “Perspective Transformation,” Adult Education 28, no. 2 (1978): 100–110, doi: 10.1177/074171367802800202.

15 J. Habermas, Knowledge and Human Interests (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1971).

16 J. Mezirow, “Transformative Theory of Adult Learning,” in In Defense of the Lifeworld, ed. M. Welton (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1995).

17 K.M. Brown, “Leadership for Social Justice and Equity: Weaving a Transformative Framework and Pedagogy,” Educational Administration Quarterly 40, no. 1 (2004), 77–108.

18 S. Brookfield, Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc., 1995).

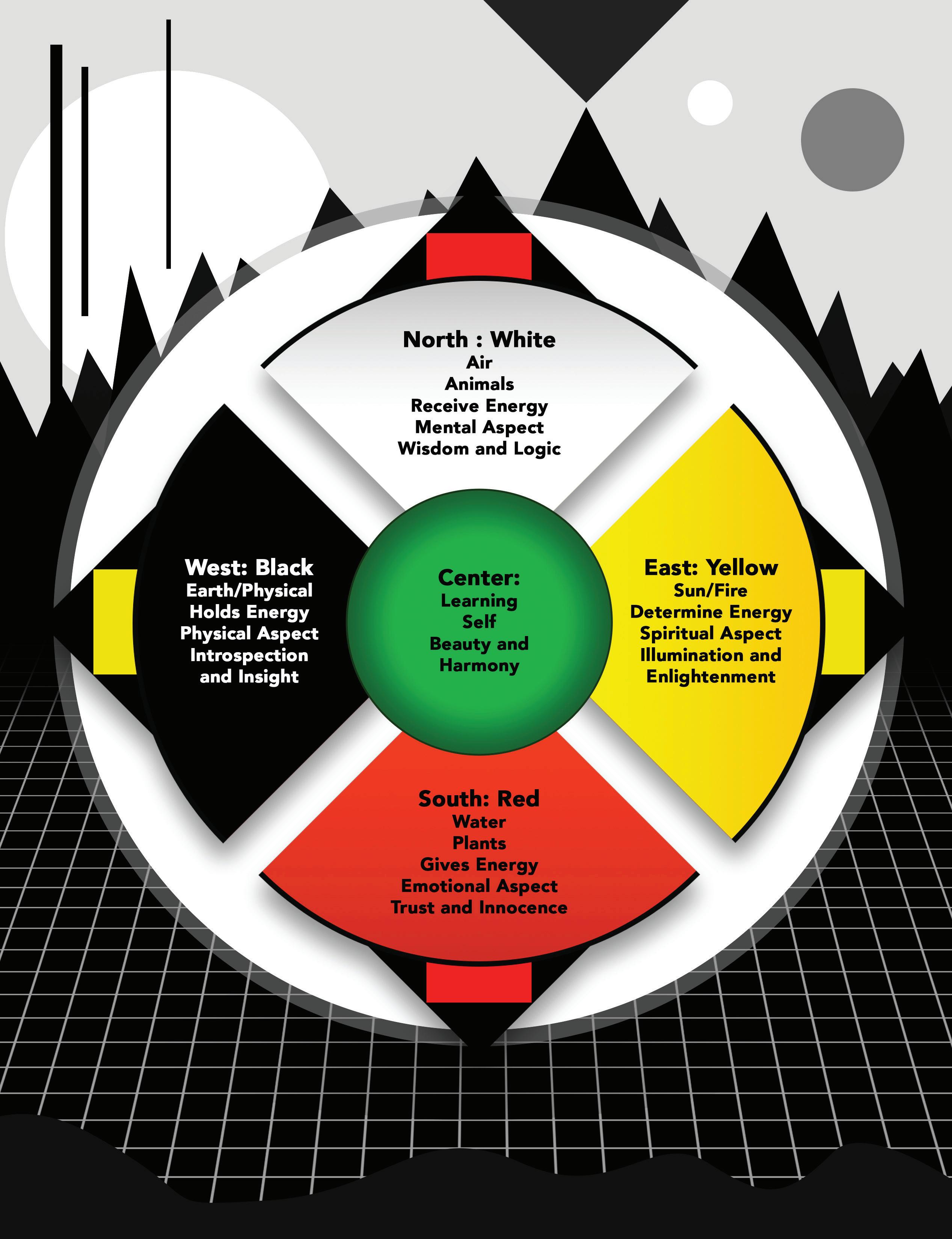

The theories and bodies of work on navigating complexity, social justice and racial equity leadership and transformative learning are incredibly timely and powerful, but these ideas are not new. Indigenous, Aboriginal, and Native communities have been practicing more interconnected ways of being for generations. For example, Indigenous communities have always emphasized the wholeness and interconnections of people and Earth. In “The Catalyst Way,” Spiller discusses the Māori “Tangata Whakapapa,” embracing the wholeness of people, as well as “Te tōrino haere whakamua, whakamuri,” or the journey of going forward as well as returning, which captures the process of embracing our interconnection to the present, future and past. In Indigenous American communities, these concepts have been referred to as the sacred hoop or sundance circle, and represent the never-ending circle of life.

Throughout the years, many healing groups have adapted these frameworks into what is often described as a medicine wheel. It consists of four quadrants that represent a stage of life: air, sun/fire, water, earth/physical. The circle represents the interconnectedness of all aspects of one’s being, including our connection to the natural world.

The simplicity, wholeness, and robustness of the medicine wheel framework makes it an ideal starting point for the development of what I call the Pressure Point Forecast. This forecast is a framework for several functions. First, it can serve as a diagnostic tool to help programs gain situational awareness of how their communities and networks are doing, and inform and align program offerings to community needs. Second, it can help shift traditional leadership development support and pedagogy, by centering it around the goal of making leaders “whole”: centering and focusing on the intersection of the multiple internal and external pressures changemakers face. Third, it can establish the foundation for more authentic mutual learning and collaboration by finding connective tissue across the common pressure points experienced by changemakers across regions, issues, areas and programs, rather than focusing just on professional connective tissue. To that end, it can be used to foster critical internal/external reflection by naming and defining the very real process that changemakers go through in aligning, negotiating, healing and connecting their present, past and future selves. This addresses the concern that more traditional leadership development work prioritizes a changemaker’s professional life and identity — while much of changemaking is a very individual journey and reactions and adaptations to a series of internal and external contexts, many of which seem to be getting more complex.

The concept of pressure points is also meant to be neutral. In the physical world, touching pressure points can elicit different responses when touched. For example, traditional Asian medicine teaches that pushing down on pressure points, such as through acupuncture or reflexology, can release tension or new energy, which can be leveraged to create catalytic momentum or steer in a new direction. Pressure points also can be used to emphasize critical junctures or defining moments or intersections. Finally and conversely, ignoring pressure points can be destabilizing, while pushing too hard on them without enough awareness and protection can be paralyzing. In karate, for example, you can knock someone out by pushing hard on critical pressure points such as in the stomach or gallbladder.

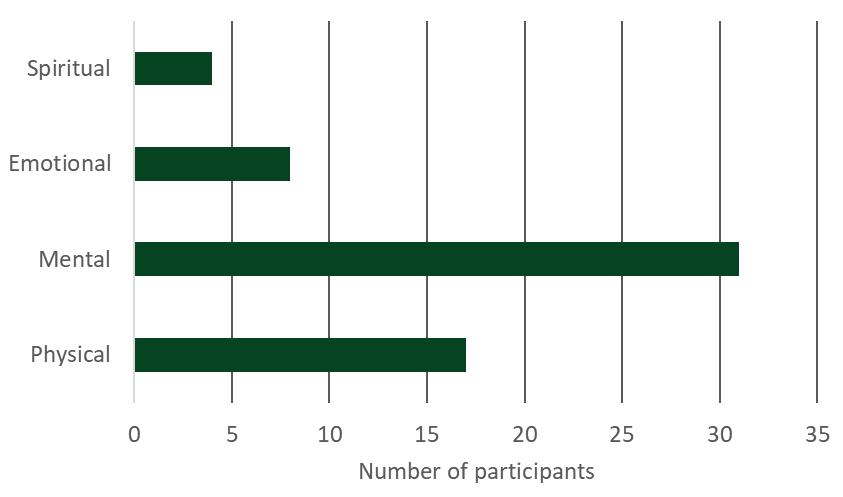

The Pressure Point Forecast provides a three-level taxonomy of pressure point areas identified by the Fellows:

• The first layer involves the four main pressure point areas shown on the medicine wheel: mental, spiritual, emotional and physical.

• The second layer encompasses the specific past (e.g., familial and ancestral), the present (e.g., trapped in bureaucracy, not feeling professionally fulfilled, lacking resources and pressure to scale) and future-sensing situations (e.g., not familiar with technology and new realities following a pandemic).

• The last layer focuses on feelings and action, such as alleviating, pressing on or navigating around pressure points through leadership practices and values.

Table 1: Centering humanity, centering complexity and the chamber of discomfort

Navigation through feeling and doing Essential leadership practices and driving values

Presence of time

Main pressure points

Present, past and the future

Mental, spiritual, emotional and physical

Through its focus on areas of growth, pain points and other internal and external pressures that Global Atlantic Fellows experience, the Pressure Point Forecast can be used as a tool to go deeper into some areas of the spiral, outlined in “The Catalyst’s Way, ” such as the chamber of discomfort and the four dimensions of “interbeing,” self, community and world that Spiller discusses.

“In Mumbai where I live, the work that sustains me is outside of the traditional professional spaces. When I work with sex workers, I rely on feminist principles of collective care, solidarity, curiosity, listening, compassion and self-expression. This is the work I most care about, that makes me human and sustains me.” She quickly shared this reflection with one of her fellow board members. She had just been selected to join the board of a medium-sized nonprofit organization and she swore to herself that the only way she would accept this position was if she could bring her “real self” to these more professionalized social change spaces. Afraid of needing to “perform” for the other NGO professionals, she was relieved to find that some of them were willing to step out of their professional shells too and have more candid conversations about the challenges and the struggles of the work. In spite of this, she still wondered how long she could maintain a facade in a setting that was not anchored in the values she so deeply cherished.

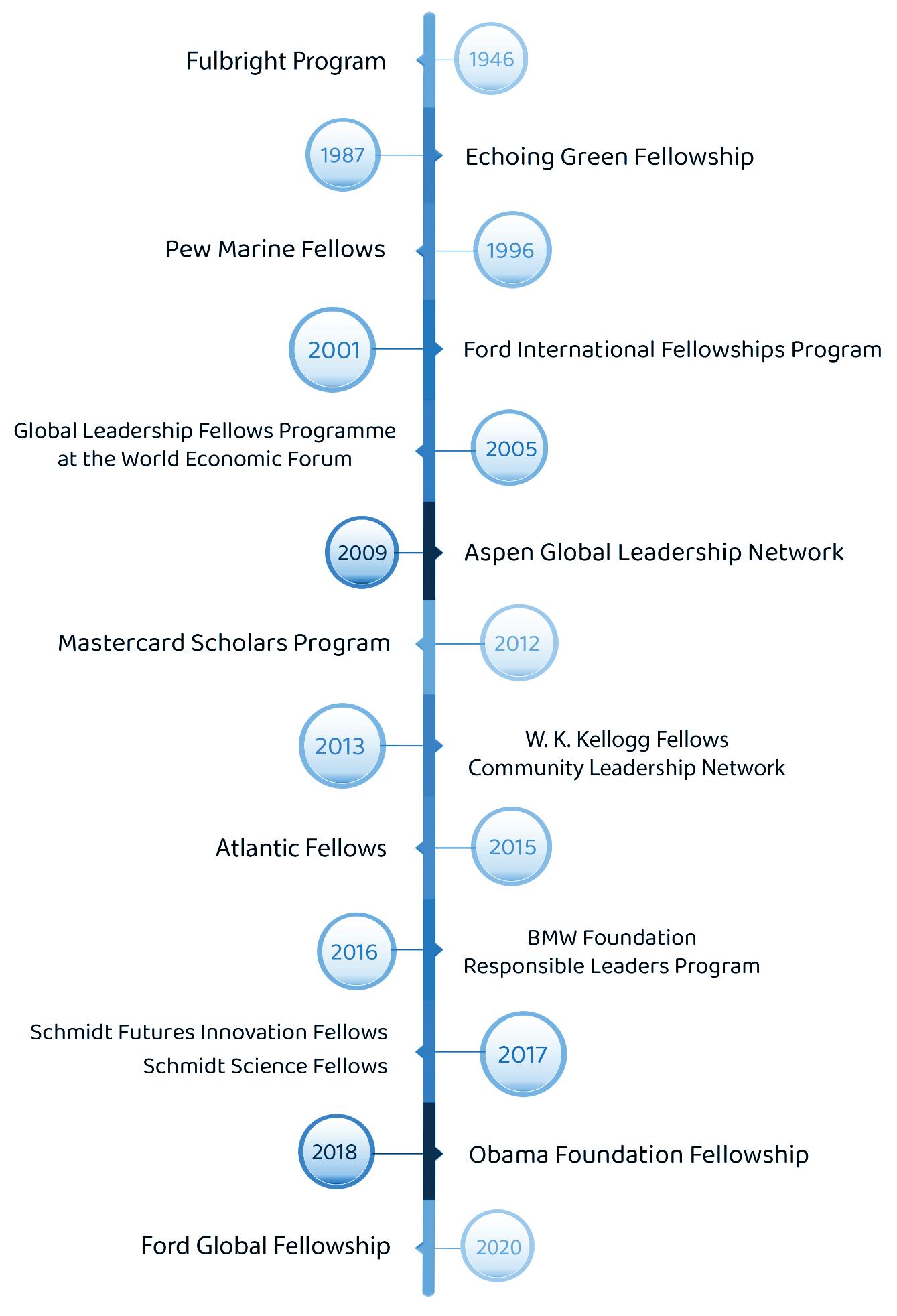

Among the growing number of leadership development programs at the national and global levels, most are aimed at or mostly accessible to leaders in the Global North. Discernible in the last ten years, however, is a small but growing focus on regions of the Global South. Mary McDonnell, a strategist who has worked for The Atlantic Philanthropies and Atlantic Fellows programs for years, assisted me in identifying 12 programs that cater to global communities. In the past three years, we have seen an increase in leadership programs designed to support and build a global network of changemakers, as shown in the timeline and table overleaf. Furthermore, there has been an explicit focus since 2001 on “transformative” social change goals and values, and on “the world’s most urgent issues and problems”, including inequality.

It’s important to note how the historical trajectory of these fellowships has shifted toward more social justice values and goals, which have grown within an infrastructure and culture emphasizing professionalism and expertise. For many of the Global Atlantic Fellows that I spoke to, these two factors are the ones that most conflict with the way they want to do the work and the change they want to see in the world. This dynamic gets in the way of leaders/changemakers being able to break free from a professional career that is often focused on maintaining the status quo and engaging in the kind of short-term decision-making that fragments their commitment to social change causes and hinders intergenerational investment. Since many Global Atlantic Fellows see their work as reshaping power hierarchies and structures, these emphases are especially challenging. Therefore, the Atlantic Institute, in partnership with the seven Atlantic Fellows programs, supports a growing community of Global Atlantic Fellows. This stands out as one of the most equity- and community-focused, multidisciplinary global leadership development programs currently available — and has a unique opportunity and responsibility to pave a new trajectory. As a result, while some may ask if there is a distinctive approach to the Atlantic Fellows programs, the answer is, there could be, if the Atlantic Institute and the Atlantic Fellows programs double down on the elements that make the Global Atlantic Fellows as unique as they are.

1: Timeline of global fellowship programs

Name Year started Program goals

Fulbright19 1946 Enables graduate students, young professionals and artists from abroad to conduct research and study in the United States.

Echoing Green Fellowship 1987 Seeks leaders who bring deep knowledge and passion to designing solutions with and for their communities.

Pew Marine Fellows20 1996 Supports mid-career scientists and other experts from around the world to advance knowledge and innovation in ocean protection.

Ford International Fellowships Program21 2001 Supports advanced studies for social change leaders from the world’s most vulnerable populations.

Global Leadership Fellows Programme of the World Economic Forum

Aspen Global Leadership Network

2005 Develops leaders who can understand and navigate complex, dynamic systems and cultivate a shared vision for change.

2009 Serves a growing, worldwide community of entrepreneurial leaders from business, government and the nonprofit sector who share a commitment to enlightened leadership and to using their extraordinary creativity, energy and resources to tackle the foremost societal challenges of our times.

Mastercard Scholars Program 2012 Envisions a transformative network of young people and institutions driving inclusive and equitable socioeconomic change in Africa.

W. K. Kellogg Fellows Community Leadership Network

2013 Develops the leadership skills of individuals who will be communitybased social change agents working to help vulnerable children and their families achieve optimal health and well-being, access to good food, academic achievement and financial security.

Atlantic Fellowship 2015 Empowers catalytic communities of emerging leaders to advance fairer, healthier, more inclusive societies.

BMW Foundation Responsible Leaders Program

Schmidt Futures Innovation Fellows

2016 Promotes responsible leadership and inspires leaders worldwide to work toward a more peaceful, just and sustainable future.

2017 Supports extraordinary mid-career individuals and teams with ideas to leverage technology thoughtfully to solve important societal challenges.

Schmidt Science Fellows 2017 Develops the next generation of science leaders to transcend disciplines, advance discovery and solve the world’s most pressing problems.

Obama Foundation Fellowship 2018 Supports outstanding civic innovators — leaders who are working with their communities to create transformational change and addressing some of the world’s most pressing problems.

Ford Foundation Global Fellowship 2020 Aims to connect and support the next generation of leaders from around the world who are advancing innovative solutions to end inequality.

Several factors stand out when looking at the evolution of global leadership development fellowships since the 1940s. Initially focused on mid-career professionals or academics, the array of programs has expanded over time to include a broader set of backgrounds and participants unified by a commitment to affecting social change. While many of these fellowships continue to emphasize hard sciences, some are increasingly curating multidisciplinary and cross-sectoral networks.

19 Mary McDonnell noted that there are other international fellowships among the 200 programs in 180 countries managed by the Institute of International Education. While a search of IIE fellowship offerings brings up 24, most seem to be in specific locations, per funding source interests, such as in East Asia, China, Central Europe or Africa, though a few are globally focused, but topically narrow.

20 McDonnell has noted that there are probably other Pew programs that run similar global fellowship programs.

21 This Ford fellowship program ended in 2011, but at one point covered 22 countries

“I am based in Johannesburg, but I approach the work very globally. I look for opportunities where I can exchange ideas with colleagues in Canada, the U.S., Germany, Australia or New Zealand. Likewise, I feel that these colleagues have also been open to learning about how we’ve approached transitional justice here in South Africa. So much of what I do is still about challenging institutions, but because no country has gotten it perfectly right, we need those spaces for learning, dreaming and experimenting together. It’s hard to make the time to do this and sometimes a top-down approach is needed to bridge and hold those connections and conversations.”

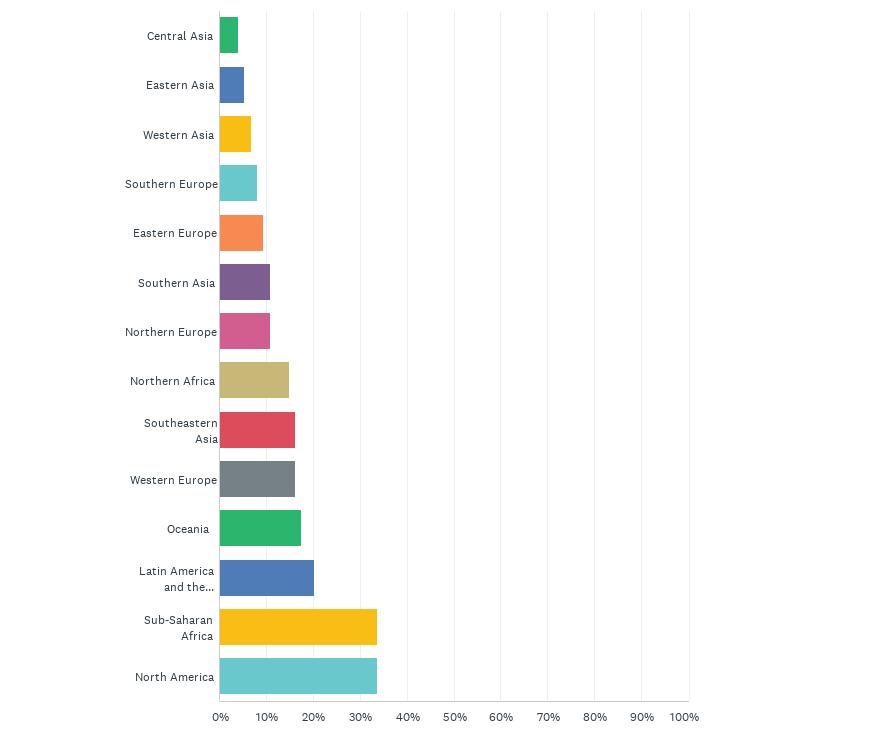

From May 2022 to January 2023, I surveyed and interviewed 85 Global Atlantic Fellows from across the seven Atlantic Fellows programs.22 In this hybrid survey/interview, there were two parts: the first half consisted of multichoice questions designed to gather fellowship, demographic and other background information, along with a list of leadership practices they used; the second part included open-ended questions about those practices and their personal, professional and life trajectories including opinions on technological change and driving values. Fellows had the choice of completing the survey with me (with the interviewer recording their answers as they spoke) or completing it on their own. All but 11 Fellows chose to interview with me. As a result, there were some inconsistencies between those who were interviewed (with responses recorded verbatim) and those who filled out their responses on their own. Nonetheless, resounding themes emerged.

First, let’s look at the demographics. Participants from the Atlantic Fellows for Equity in Brain Health program made up nearly a third of the participants (32.43%), followed by the Atlantic Fellows for Social and Economic Equity (16.22%) and Atlantic Fellows for Healthy Equity in U.S. + Global (14.86%).

Though seeking as much global representation as possible, most participants were based in North America (33.78%) and sub-Saharan Africa (33.78%), with significant but smaller shares from Latin America and the Caribbean (20.27%) and Oceania (17.57%).

22 The list of survey/interview questions can be found in Appendix 1.

Table 3: Responses by program Percentage of Global Atlantic Fellows

Table 4: Participation by region

Q3 What region(s) do you work in?

Fellows are often involved in more than one issue area, so the total exceeds 100%. Given this, the top five issue areas that Fellows worked in were: education and learning (28%); democracy, power and governance (29.33%); equality, diversity and inclusion (41.33%); poverty, inequality and social justice (46.67%); and health and well-being (73.33%). Meanwhile the top five areas or strategies represented are medicine and health provider (21.33%); teaching and education (in schools, academia or public education) (33.33%); organizing, movements, etc. (33.33%); policy, advocacy, etc. (48%); and research (e.g., academic, nongovernmental organization) (60%).

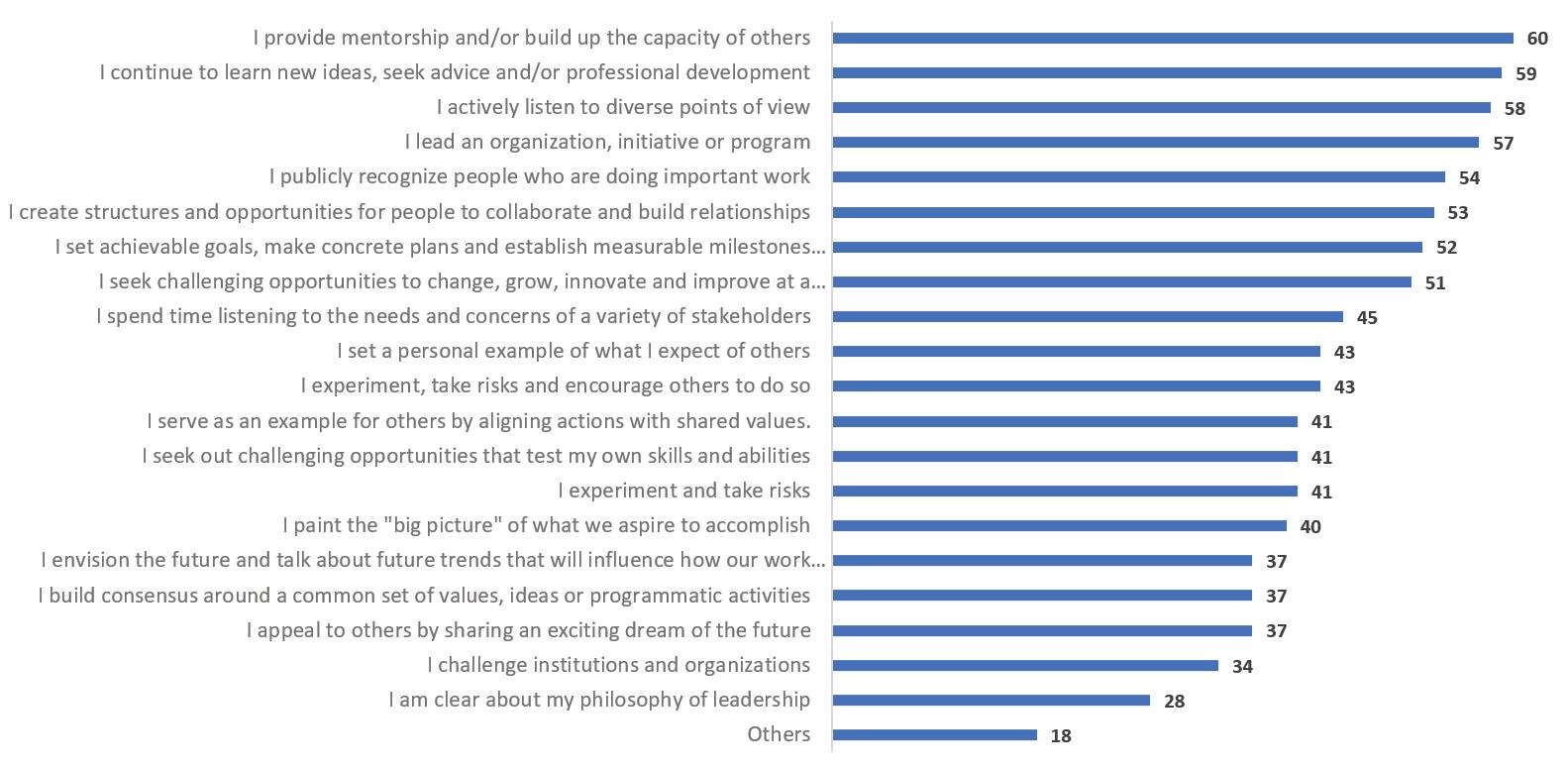

Because my map of pressure points emphasizes an adaptive approach to leadership, I also wanted to identify what leadership practices Global Atlantic Fellows utilize and how frequently they do so. The list of leadership practices is based on the Leadership Practices Inventory developed by scholars James M. Kouzes and Barry Posner.23 Their inventory is designed to measure the unique leadership style of current managers, executives and other types of organizational leaders. Because they interviewed more than 75,000 leaders, their inventory of practices is the most comprehensive, identifying how leaders act, think and feel in their positions.

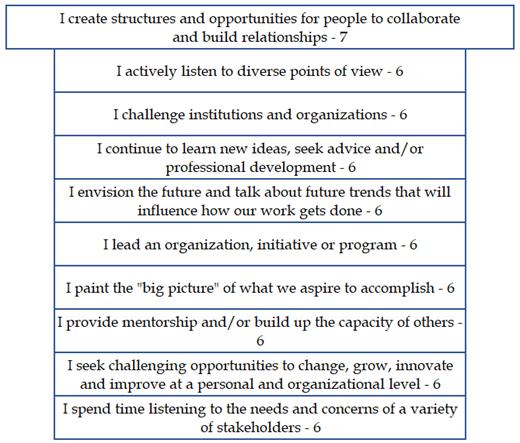

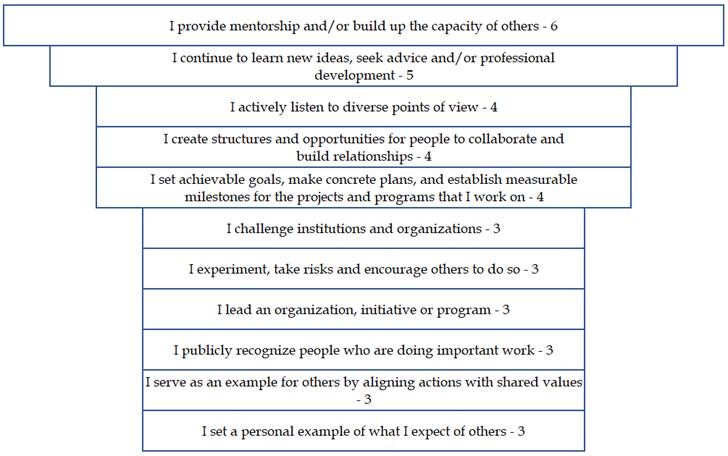

In my outreach, 49% of Fellows selected more than 11 leadership practices,24 which is quite robust, while 51% selected fewer than 11 practices. The top five practices most selected are: providing mentorship; learning new ideas and seeking advice/professional development; actively listening to diverse viewpoints; leading an organization, initiative or program; and publicly recognizing people doing good work. The least selected practices were being clear about their philosophy of leadership; challenging institutions and organizations; appealing to others by sharing an exciting dream of the future; building consensus around a common set of values, ideas or activities; and envisioning the future and talking about future trends.

Figure 2: Selection frequency of the leadership practices

23 J. M. Kouzes and B. Z. Posner, The Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership, second edition (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

24 On average, Global Fellows selected 11.33 leadership practices out of 17 practices.

Fellows noted other leadership practices that are not on this inventory including:

• Using different types of decision-making, with ethical or equitable decision-making most commonly identified.

• Holding complexity, including creating space for differences.

• Employing conflict mediation.

Ethical leadership surfaced in some of the conversations about decision-making styles, but there seems to be a lack of a clear understanding of what it entails. Max Price, who is a consultant and former vice chancellor at the University of Cape Town, recently served as an Atlantic Institute Reader-in-Residence. As part of this work, he interviewed Atlantic Fellows and some program staff on ethical decision-making. From these interviews he noted that the concept is used rather loosely. For example, when pressed to say what they mean, Fellows often refer to leading with integrity: a refusal to lie, steal or deceive in any way; incorruptible; trustworthy, dependable, consistent and honoring one’s word and commitments. In other words, the concept is being used more to describe personality traits than an approach to making tough morally informed decisions.

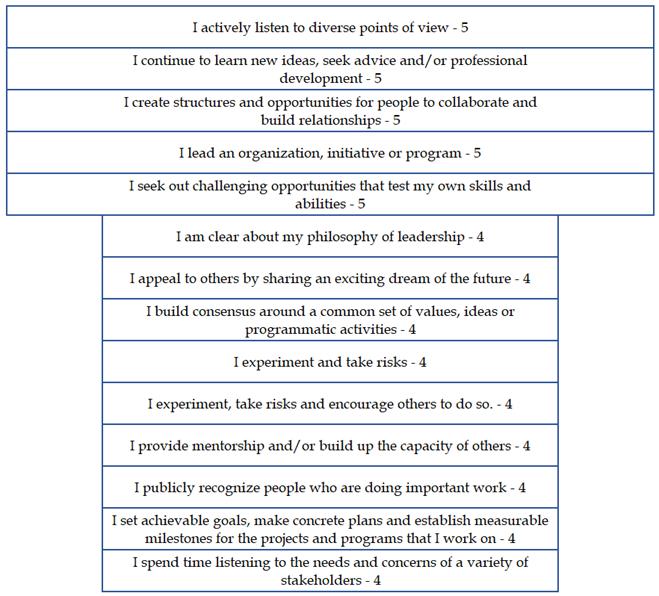

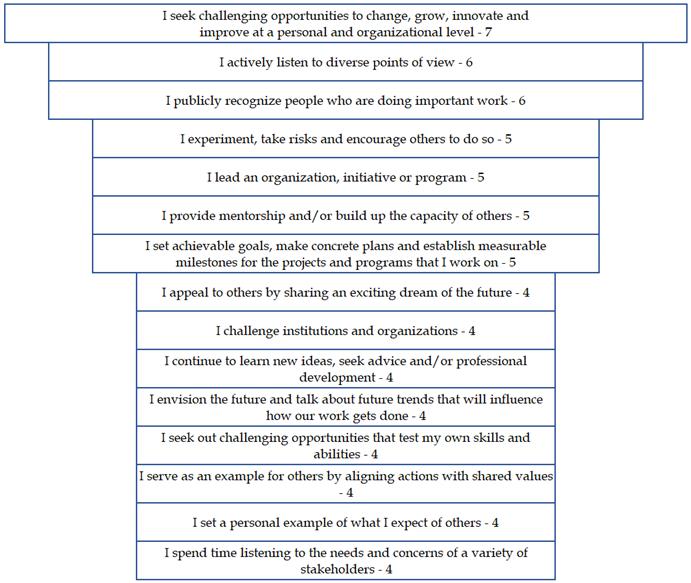

Leadership practices vary across Atlantic Fellowship programs. Global Atlantic Fellows from all three of the health equity programs held the most traditional leadership positions, with most indicating they lead an organization, program or initiative. Among those from the racial equity program, publicly recognizing good work was one of the top three leadership practices. In contrast, only those from the social equity program included challenging institutions as one of their top three leadership practices.

Figure 3: Top leadership practices by program (including frequency of selection)

Atlantic Fellows for Equity in Brain Health

Atlantic Fellows for Health Equity in Southeast Asia

Atlantic Fellows for Healthy Equity in U.S. + Global

Atlantic Fellows for Racial Equity

Atlantic Fellows for Social and Economic Equity

The top five issue areas of work identified by Fellows are:

• Health and well-being (73.33%).

• Poverty, inequality and social justice (46.67%).

• Equality, diversity and inclusion (41.33%).

• Democracy, power and governance (29.33%).

• Education and learning (28%).

Meanwhile the top five areas or strategies represented are:

• Research (e.g., academic, nongovernmental organization) (60%).

• Policy and advocacy (48%).

• Organizing movements (33.33%).

• Teaching and education (in schools, academia or public education) (33.33%).

• Medicine and providing health services (21.33%).

To get a more granular look at the leadership practices utilized by Global Atlantic Fellows, the top five issue areas are broken out by strategies and leadership practices. This cross tabulation reveals a few themes, and a discussion of key findings follows each issue area.

Based on the survey, Global Atlantic Fellows who work on health and well-being have a limited range of leadership practices, mostly concentrated on research, teaching and education, and policy/advocacy. Meanwhile, Global Atlantic Fellows who work on this issue but tend to have strategies that engage business or private-sector work, technology or data or media and communication strategies — tend to have significantly fewer practices to draw on in their day-today work. Most of their leadership practices were focused on learning new ideas, seeking advice, and or professional development. Meanwhile, the practice of painting a “big picture” of what to accomplish (in private-sector work) was the least checked off.

I actively listen to diverse points of view

I am clear about my philosophy of leadership

I appeal to others by sharing an exciting dream of the future

I build consensus around a common set of values, ideas or programmatic activities

I challenge institutions and organizations

I continue to learn new ideas, seek advice and/or professional development

I create structures and opportunities for people to collaborate and build relationships

I envision the future and talk about future trends that will influence how our work gets done

I experiment and take risks

I experiment, take risks and encourage others to do so

I lead an organization, initiative or program

Figure 5: Health and well-being

I paint the “big picture” of what we aspire to accomplish

I provide mentorship and/or build up the capacity of others

I publicly recognize people who are doing important work

I seek challenging opportunities to change, grow, innovate and improve at a personal and organizational level

I seek out challenging opportunities that test my own skills and abilities

I serve as an example for others by aligning actions with shared values.

I set a personal example of what I expect of others

I set achievable goals, make concrete plans and establish measurable milestones for the projects and programs that I work on I spend time listening to the needs and concerns of a variety of stakeholders

Others

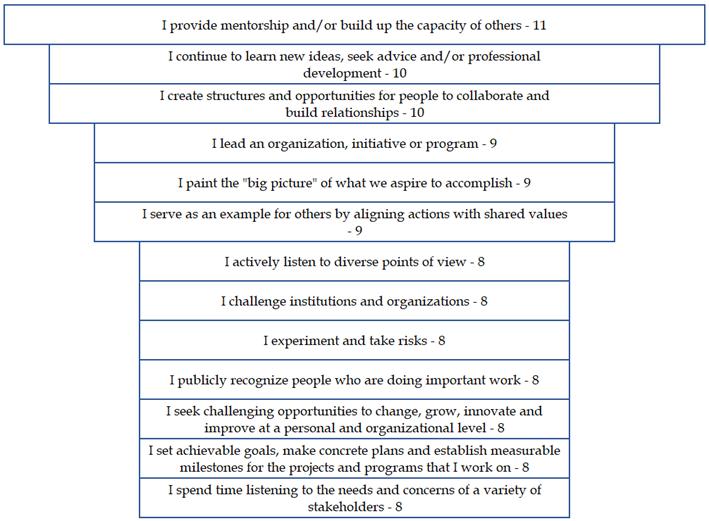

Global Atlantic Fellows who work in issue areas related to poverty, inequality and social justice identified a wider range of practices. For example, those working in research and policy include the most variety of leadership practices, followed by those organizing movements. The strategies that had the least variety in leadership practices were once again direct services, business and private-sector work; and medicine and health providers. The most often checkedoff practices for this issue area in the research strategy include actively listening to diverse points of view; continuing to learn new ideas, seeking advice and/or professional development; and setting achievable goals, making concrete plans and establishing milestones.

I actively listen to diverse points of view

I am clear about my philosophy of leadership

I appeal to others by sharing an exciting dream of the future

I build consensus around a common set of values, ideas or programmatic activities I challenge institutions and organizations

I continue to learn new ideas, seek advice and/ or professional development

I create structures and opportunities for people to collaborate and build relationships

I envision the future and talk about future trends that will influence how our work gets done

I experiment and take risks

I experiment, take risks and encourage others to do so

I lead an organization, initiative or program

I paint the “big picture” of what we aspire to accomplish I provide mentorship and/ or build up the capacity of others

I publicly recognize people who are doing important work

I seek challenging opportunities to change, grow, innovate and improve at a personal and organizational level I seek out challenging opportunities that test my own skills and abilities

I serve as an example for others by aligning actions with shared values.

I set a personal example of what I expect of others

I set achievable goals, make concrete plans and establish measurable milestones for the projects and programs that I work on I spend time listening to the needs and concerns of a variety of stakeholders

Others

Global Atlantic Fellows working on issues related to democracy, power and governance had a limited range compared to colleagues focusing on other issue areas. My analysis found that those working in the business/private sector, creative spaces, teaching and education or medicine have the least variety in their leadership practices. Meanwhile, those working in policy/ advocacy, research and organizing movements had the most amount of variety in their practices. Interestingly, for this issue area and in the strategy of policy/advocacy, the most common practice selected was envisioning the future and identifying future trends.

Figure 7: Democracy, power and governance

I actively listen to diverse points of view

I am clear about my philosophy of leadership

I appeal to others by sharing an exciting dream of the future

I build consensus around a common set of values, ideas or programmatic activities

I challenge institutions and organizations

I continue to learn new ideas, seek advice and/ or professional development

I create structures and opportunities for people to collaborate and build relationships

I envision the future and talk about future trends that will influence how our work gets done

I experiment and take risks

I experiment, take risks and encourage others to do so

I lead an organization, initiative or program

I paint the “big picture” of what we aspire to accomplish I provide mentorship and/or build up the capacity of others

I publicly recognize people who are doing important work

I seek challenging opportunities to change, grow, innovate and improve at a personal and organizational level

I seek out challenging opportunities that test my own skills and abilities I serve as an example for others by aligning actions with shared values.

I set a personal example of what I expect of others

I set achievable goals, make concrete plans and establish measurable milestones for the projects and programs that I work on

I spend time listening to the needs and concerns of a variety of stakeholders

Others

Those working on education and learning selected a wide range of practices, and there was less cohesion around key practices. Instead, what I found is that research and teaching had the greatest number of practices identified, while those working on creative spaces, technology/ data and direct services had a more limited range. For this issue area, mentoring and building the capacity of others was the most commonly selected practice.

I actively listen to diverse points of view

I am clear about my philosophy of leadership

I appeal to others by sharing an exciting dream of the future

I build consensus around a common set of values, ideas or programmatic activities

I challenge institutions and organizations

I continue to learn new ideas, seek advice and/ or professional development

I create structures and opportunities for people to collaborate and build relationships

I envision the future and talk about future trends that will influence how our work gets done

I experiment and take risks

I experiment, take risks and encourage others to do so

I lead an organization, initiative or program

I paint the “big picture” of what we aspire to accomplish

I provide mentorship and/ or build up the capacity of others

I publicly recognize people who are doing important work

I seek challenging opportunities to change, grow, innovate and improve at a personal and organizational level

I seek out challenging opportunities that test my own skills and abilities

I serve as an example for others by aligning actions with shared values.

I set a personal example of what I expect of others

I set achievable goals, make concrete plans and establish measurable milestones for the projects and programs that I work on

I spend time listening to the needs and concerns of a variety of stakeholders

Others

Finally, Global Atlantic Fellows who work on equality, diversity and inclusion issue areas tend to have a wide range of practices across strategies. Global Atlantic Fellows working in research, teaching and education as well as policy and advocacy tended to have the most amount of variety. Fellows working on direct-services strategies had the shortest list of practices, followed by those who work in creative spaces. The most commonly selected practices in the research strategy included: continuing to learn new ideas, seek advice, etc.; setting achievable goals and concrete plans; and providing mentorship and capacity building for others.

I actively listen to diverse points of view

I am clear about my philosophy of leadership

I appeal to others by sharing an exciting dream of the future

I build consensus around a common set of values, ideas or programmatic activities

I challenge institutions and organizations

I continue to learn new ideas, seek advice and/ or professional development

I create structures and opportunities for people to collaborate and build relationships

I envision the future and talk about future trends that will influence how our work gets done

I experiment and take risks

I experiment, take risks and encourage others to do so

I lead an organization, initiative or program

I paint the “big picture” of what we aspire to accomplish

I provide mentorship and/ or build up the capacity of others

I publicly recognize people who are doing important work

I seek challenging opportunities to change, grow, innovate and improve at a personal and organizational level

I seek out challenging opportunities that test my own skills and abilities

I serve as an example for others by aligning actions with shared values.

I set a personal example of what I expect of others

I set achievable goals, make concrete plans and establish measurable milestones for the projects and programs that I work on

I spend time listening to the needs and concerns of a variety of stakeholders

Others

In conclusion, the strategies of research and policy/advocacy generally tend to be associated with more leadership practices across all issue areas, while those working on direct services or in the private sector tend to check off the fewest practices. While organizing movements was among the top strategies utilized by Global Atlantic Fellows, this strategy did not have a strong concentration of leadership practices. Health and well-being was the only issue area where this strategy had a notable number of leadership practices. For this issue area, those working on movements and organizing noted the practice of being clear about leadership philosophy. Finally, I want to point out that technology — the area I see as likely to increase complexity for Fellows — is the only issue area where there was a strong concentration of leadership practices in migration, mobilities and movements. Global Atlantic Fellows working at this intersection are not only unique in their familiarity with technology, but also have a wide range of leadership practices to draw from and use. In contrast, Global Atlantic Fellows working on issues related to hunger, food and power had the least familiarity with technology strategies and leadership practices to help them navigate this space.

I actively listen to diverse points of view

I am clear about my philosophy of leadership

I appeal to others by sharing an exciting dream of the future

I build consensus around a common set of values, ideas or programmatic activities

I challenge institutions and organizations

I continue to learn new ideas, seek advice and/ or professional development

I create structures and opportunities for people to collaborate and build relationships

I envision the future and talk about future trends that will influence how our work gets done

I experiment and take risks

I experiment, take risks and encourage others to do so

I lead an organization, initiative or program

I paint the “big picture” of what we aspire to accomplish

I provide mentorship and/ or build up the capacity of others

I publicly recognize people who are doing important work

I seek challenging opportunities to change, grow, innovate and improve at a personal and organizational level

I seek out challenging opportunities that test my own skills and abilities

I serve as an example for others by aligning actions with shared values.

I set a personal example of what I expect of others

I set achievable goals, make concrete plans and establish measurable milestones for the projects and programs that I work on

I spend time listening to the needs and concerns of a variety of stakeholders

Others

I actively listen to diverse points of view

I am clear about my philosophy of leadership

I appeal to others by sharing an exciting dream of the future

I build consensus around a common set of values, ideas or programmatic activities

I challenge institutions and organizations

I continue to learn new ideas, seek advice and/ or professional development

I create structures and opportunities for people to collaborate and build relationships

I envision the future and talk about future trends that will influence how our work gets done

I experiment and take risks

I experiment, take risks and encourage others to do so

I lead an organization, initiative or program

I paint the “big picture” of what we aspire to accomplish

I provide mentorship and/or build up the capacity of others

I publicly recognize people who are doing important work

I seek challenging opportunities to change, grow, innovate and improve at a personal and organizational level

I seek out challenging opportunities that test my own skills and abilities

I serve as an example for others by aligning actions with shared values.

I set a personal example of what I expect of others

I set achievable goals, make concrete plans and establish measurable milestones for the projects and programs that I work on

I spend time listening to the needs and concerns of a variety of stakeholders

Others

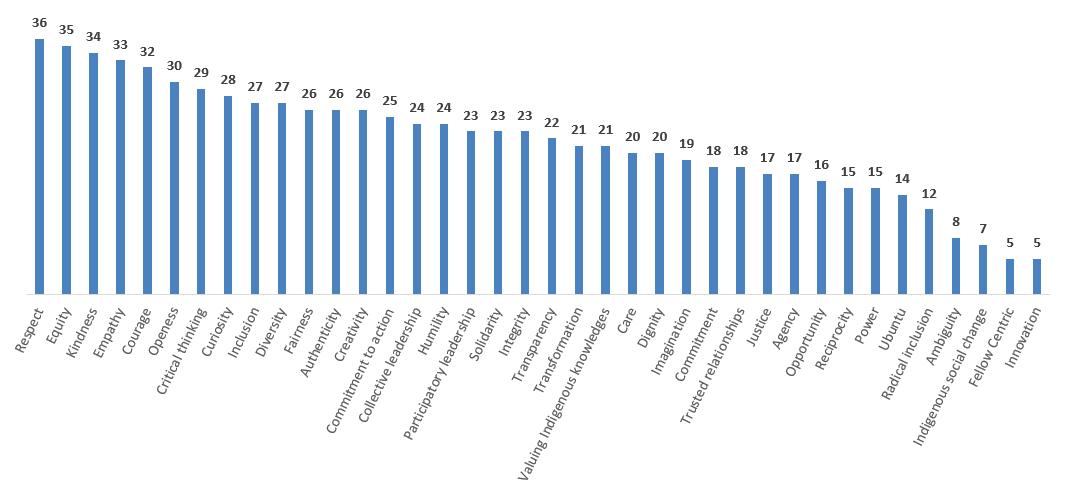

My analysis also looked at a Fellow’s values as guides in navigating complexity and in building more adaptive practices. Fellows identified the following values as the top ten: respect, equity, kindness, empathy, courage, openness, critical thinking, curiosity, inclusion and diversity. The values that were least selected were: innovation, fellow-centricity, Indigenous social change, ambiguity and radical inclusion.

Frequency of values

When looking at how the top five most selected leadership practices overlap with values, I see a few trends. First, for Global Atlantic Fellows who place a strong focus on externally giving to others — either through mentoring, building the capacity of others or listening to diverse points of views — tend to be driven by core values such as fairness, kindness, respect, courage and empathy. Practices less clearly defined as having central values include leading an organization, initiative or program and publicly recognizing people who are doing important work. Leadership practices with such ambiguity toward driving values could be considered pressure points, and represent areas of tension or growth.

Values

Agency

Ambiguity

Authenticity

Care

Collective Leadership

Committment

Committment to action

Courage

Creativity

Critical Thinking

Curiosity

Dignity

Diversity

Empathy

Equity

Fairness

Fellow Centric

Humility

I provide mentorship and/or build up the capacity of others

I continue to learn new ideas, seek advise, and/or professional development

I actively listen to diverse points of view

I lead an organization, initiative, or program

I publicly recognize people who are doing important work

Imagination Inclusion

Indigenous social change

Innovation Integrity

Justice Kindness

Openess Opportunity

Participatory Leadership Power

Radical Inclusion

Reciprocity

Respect Solidarity

Transformation

Transparency

Trusted Relationships

Ubuntu Valuing Indigenous knowledges

She worked in a very bureaucratic hospital outside of Manila. She was trying to do a community survey, because that’s the part of the work she most cared about. But especially since COVID-19, the public health systems have been overstretched and underresourced. Therefore, as of late she feels like she spends most of her time navigating the bureaucracy, run mostly by men, and listening to everyone’s frustrations. “I find it so hard to navigate. I feel like to do clinical work and push for institutional change you need different personalities. Sometimes you have to try to make everyone happy and comfortable, and other times you have to be more aggressive and be the chief to push for the change that needs to happen. And I lack the confidence to be the chief. I feel like I still have imposter syndrome and I don’t feel comfortable sharing my ideas in meetings. Therefore, it will be really hard for me to push for the institutional change that needs to happen here.”

So far I’ve discussed how the work of social change and fostering equity is getting increasingly complex and urgent due to a variety of geopolitical, socioeconomic and technological issues. I discussed how leadership theories grounded on the interaction between the self and the broader environment is foundational to fostering greater adaptive and reflective responses. Additionally, transformative adult learning theory shows us how this can be done by creating spaces for more critical reflection, and recognizes the centrality of leaders’ experiences in their life journeys. Borrowing concepts and frameworks from “The Catalyst’s Way” chamber of discomfort, I set out to develop the Pressure Point Framework as a tool to help foster critical reflection on the multiplicity of internal and external forces that leaders often have to negotiate.

In this section, I unpack and apply the Pressure Point Framework to the 85 surveys/interviews discussed in the previous section, to demonstrate how it can be used to identify areas of pressure, tension and opportunities in leaders’ journeys and experiences. Because the analysis was over 100 pages long,25 I’ve chosen to highlight the most statistically significant findings to demonstrate this framework as an approach to reconstructing leadership studies by centering the experiences of changemakers, and in this case, the Global Atlantic Fellows.

25 I conducted the analysis on this section comparing Global Atlantic Fellows working in the Global North and Global South, but it is excluded to keep the report as brief as possible.

I coded the open-ended questions according to two independent coding schemes:

• The first was the meta-level trend classification inspired by the Indigenous medicine wheel. I used the following four quadrants as a guide to identify pressure points:

o Physical.

o Mental.

o Emotional.

o Spiritual.

• The second coding scheme classified answers based on intersecting trends that came up across all of the surveys and interviews or were emerging areas of complexity for Global Atlantic Fellows (such as technological complexity). I broke those trends into six overarching themes:

o Familial complexity: Fellows either talked about early familial and parental influences, noting how they shaped their development and trajectory; and/or early hopes and dreams, discussing early career aspirations or any reflections about the early parts of their careers and when they switched over to more equity and social change work.

o Organizational, institutional and/or systemic complexity: Fellows described the challenges of working with institutions. For example, many Fellows talked about being “trapped in systems” they are trying to change and challenge. They also talk about wanting to experiment and do things in new ways and the friction they encounter when up against hierarchy and traditional power structures. They talk about frustrations with incremental change and wanting more systemic change.

o Relational complexity: Fellows talked about engaging in complex interpersonal work such as bridging work, conflict resolution, holding space for differences and stakeholder engagement. Some Fellows also talked about their concerns of not being close to marginalized or grassroots communities they ultimately want to serve, either because of having to go up the ladder or due to the changing nature of the work.

o Leadership complexity: Fellows discussed their reflections such as not feeling like a “leader,” or not having a clear vision or leadership philosophy or not feeling confident. Some Fellows talked about leadership areas they have to work on, such as having to be “more vocal” and “more visible” to become more effective. Some Fellows also highlighted their leadership strengths such as being entrepreneurial and innovative. Finally, some Fellows also shared leadership lessons or insights they have learned along the way that are helpful to them.

o Societal complexity: Fellows sometimes talked about societal challenges in doing their work, such as finding it harder to have dialogue with different groups or common ground, or spoke of other challenges happening in their society or community. Some talked about having to change humanity.

o Technological change: In general, this theme did not come up unless I explicitly asked about it, as I sought to gain insight into the extent to which Fellows express being aware of how technology is changing their work, or express not having knowledge or knowing a little bit, but not being engaged in the matter. If Fellows did not have a response, I interpreted this as there not being

enough information about technology for them to be able to assess how it might affect their issue area and how they work.

The following scores/variables were derived from participants’ answers to close-ended questions:

• The number of regions the respondent works in: calculated by counting the number of geographical regions listed in Q3.

• Whether the respondent is working in more than one region: a binary variable derived from the number of regions listed in Q3. Those who listed more than one region were classified as 1; those listing a single region were assigned 0.

• Working in Global North vs. Global South; derived from Q3 about the region of the world the participant works in:

o Global North, i.e., in one of or more of the following:

• North America.

• Eastern Asia.

• Eastern Europe.

• Northern Europe.

• Southern Europe.

• Western Europe.

• Oceania.

o Global South, i.e., in one of or more of the following:

• Northern Africa.

• Sub-Saharan Africa.

• Latin America and the Caribbean.

• Central Asia.

• Southeastern Asia.

• Southern Asia.

• Western Asia.

o Both types of regions.

• The number of issue areas the respondent works in: calculated by counting the number of areas listed on Q4.

• Working in a higher number of issue areas: a binary variable created from the number of issue areas the respondent works in, by assigning 1 to those who reported working in more than three areas and assigning 0 to those working in up to three areas.

• The number of areas the respondent devotes most of the work to: calculated by counting the number of areas listed on Q5.

• Devoting most of the work to a higher number of different areas: a binary variable derived from the number of areas the respondent devotes most of the work to, and obtained by assigning value 1 to participants who reported devoting most of their time to more than three areas and assigning 0 to participants reporting devoting most of their time to up to three areas.

• “Other” option codes in Q6: open-ended answers given by participants who chose other on Q7, the question asking them to list the leadership practices they used the most. Responses were coded using the meta-level trend classification coding scheme into one of the first three categories of this scheme (physical, mental or emotional).

• Meta-level trend scores of Q6 were calculated by counting the number of selected leadership practices (see below) and dividing it by the total number of leadership practices constituting that meta-level trend. In this way, each score was a proportion of the maximum score that

can be achieved on that particular meta-level score. This was done in order to make different meta-level scores comparable, given that they consist of different numbers of indicators.

I. Dominant pressure points: Preselected list of leadership practices

Question six (Q6) of the survey/interview26 prompts the participant to select the leadership practices that most define how they show up in the field, communities, etc. The meta-level trend scores of Q6 were calculated by counting the number of selected leadership practices (from the below list) and dividing it by the number of leadership practices constituting that meta-level trend. In this way, each score was a proportion of the maximum score that can be achieved on that particular meta-level score. This was done in order to make different meta-level scores comparable, given that they consist of different numbers of indicators.

• I lead an organization, initiative, or program.

• I seek out challenging opportunities that test my own skills and abilities.

• I experiment, take risks and encourage others to do so.

• I experiment and take risks.

• I seek challenging opportunities to change, grow, innovate and improve at a personal and organizational level.

Mental:

• I am clear about my philosophy of leadership.

• I challenge institutions and organizations.

• I create structures and opportunities for people to collaborate and build relationships.

• I build consensus around a common set of values, ideas or programmatic activities.

• I envision the future and talk about future trends that will influence how our work gets done.

• I paint the “big picture” of what we aspire to accomplish.

• I set achievable goals, make concrete plans and establish measurable milestones for the projects and programs that I work on.

• I continue to learn new ideas, seek advice and/or professional development.

• I engage in conflict mediation.

Emotional:

• I publicly recognize people who are doing important work.

• I spend time listening to the needs and concerns of a variety of stakeholders.

• I actively listen to diverse points of view.

• Other: open answers that mention holding complexity or other practices belonging to this category.

26 See Appendix 1 for a list of survey/interview questions.

• I provide mentorship and/or build up the capacity of others.

• I serve as an example for others by aligning actions with shared values.

• I set a personal example of what I expect of others.

• I appeal to others by sharing an exciting dream of the future.

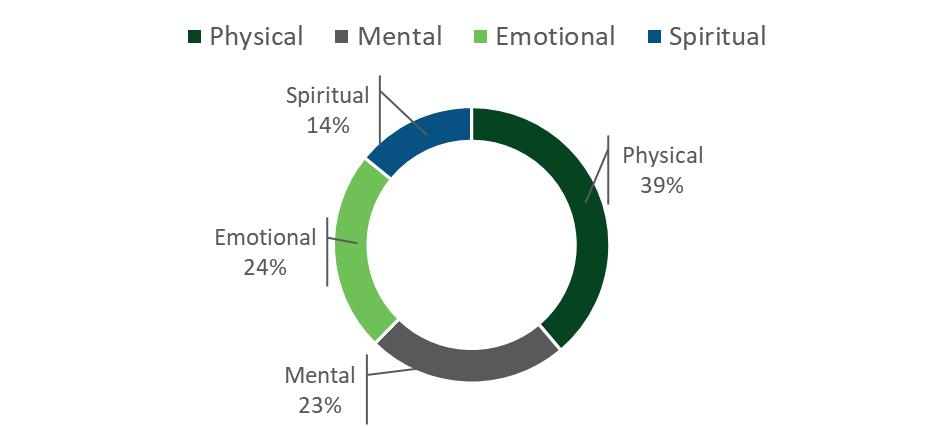

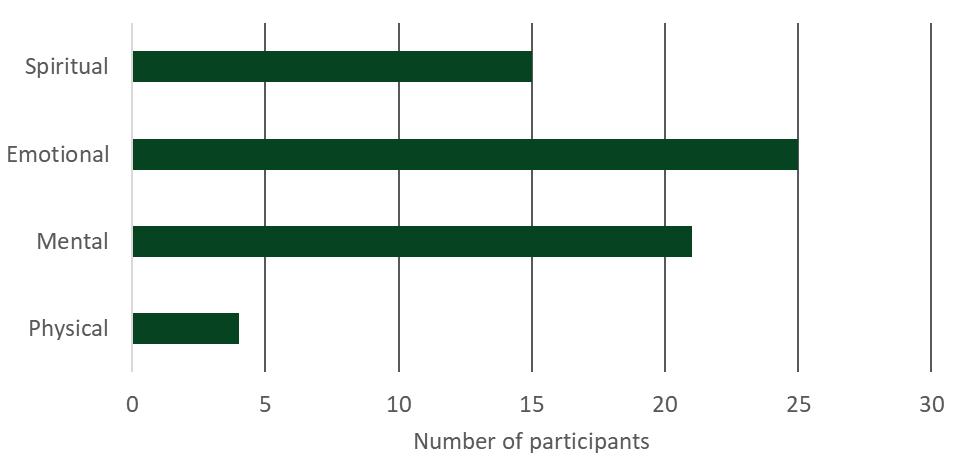

The dominant meta-level trend observed in Q6 responses was the physical area, as Fellows selected activities related to it (39%), followed by emotional (24%) and mental (23%) meta-trend levels. The number of people dominantly choosing practices related to the spiritual realm was the lowest (14%).

Q6. Most often chosen meta-level trend of leadership practices, Indigenous medicine wheel

Even though Fellows most often chose leadership practices corresponding to the physical meta-level trend (in response to Q6), their examples (prompted by Q8) tended to be in the mental meta-level category. When looking at these examples through intersecting trends, most answers were dominated by leadership complexity themes. Fellows most often reported that their leadership practices embody respect, equity and kindness, and least often that they embody innovation and indigenous social change through research and practice (Q9).

A sampling of responses from those selecting “other” to Q6 can be seen below, categorized by the four pressure points.

27 This one was a little tricker to code as it’s hard to define what spiritual intelligence is in the work of social change and equity. However, for the purposes of this study, I looked for themes focused on the traditional servant leadership style in which Global Atlantic Fellows discussed ways that they put their needs before others, and are driven by making connections to their external environment (e.g., people, world, etc.). I also looked for times when Fellows talked about their higher passions and things that fuel their will to keep going or mentioned specific activities they do to find joy including playing music, engaging in wellness activities and meditating.

Physical

• “Takes ideas into action.”

• “I have to face danger, your life may be in danger. For example, in the past week I was in a meeting with one of my colleagues and there was a strange car following us.”

• “I actively seek people who are able to collaborate, and that is very straightforward, and [I] avoid people that are very competitive.”

Mental

• “I would say I spend a lot of time doing conflict resolution/mediation.”

• “Ethical decision-making and distributed leadership/sharing power describe the way I show up in my work.”

• “My philosophy of leadership is evolving and I don’t publicly recognize people who are doing important work all the time.”

Emotional

• “I invite people to collaborate and try to support them in realizing their ideas as they want.”

• “I like to be clear about who I’m accountable to and my beliefs. One of the most important things we can do is create space to hold complexity and create space for difference. I’m especially interested in building organizations that distribute power.”

Spiritual

• “Leadership is a 24/7 role. Systems and processes allow me to delegate and replicate leadership principles by way of shared values.”

• “I use equitable decision-making in my day to day life.”

• “Building the capacity for people to engage is important to me. It’s essential to them to become a good ally.”

II. Dominant pressure points: Open-ended responses to examples of leadership practices

Question eight (Q8) was an open-ended question that asked Fellows to share examples, experiences or stories about the leadership practices they selected. In total there were over 45,000 words to analyze. I first identified 14 subthemes, which were then coded for the meta-level trend and the intersecting trend. The codes assigned to each of these contextual units were counted to form:

● Q8 meta-level trend scores: calculated by counting the number of contextual units of the content that correspond to that particular meta-level trend category, thereby determining the counts of physical, mental, emotional and spiritual answers.

● Q8 dominant meta-level trend: a categorical variable created by comparing the Q8 metalevel trend scores and assigning the value to this variable that corresponds to the highest Q8 meta-level trend score of the participant.

● Q8 intersecting trend scores: calculated by counting the number of contextual units of the content that correspond to that particular intersecting trend category, thereby creating counts of the seven intersecting trend categories.

● Q8 dominant intersecting trend: a categorical variable created by comparing the Q8 intersecting trend scores and assigning the value to this variable that corresponds to the highest Q8 intersecting trend score for the Fellow.

For the Q8 dominant meta-level trend, analysis of the long open-ended answers revealed that the largest number of Fellows primarily talked about examples from the mental meta-level trend category, followed by the physical category, as touched on above. Dominantly spiritual answers were the third most common type. Although there were a lot of contextual units with examples from the emotional area, they were much less common in the answers of individual participants.

Q8. Please provide specific examples of activities that you do for each leadership practice, dominant meta-level trends

A sampling of answers brings this to life.

Physical

• “In my work, we’re trying to bring a research collaborative, education, research and clinical initiatives together. The biggest challenge is to get them to play well together. It’s hard to get the deans of five schools to meet. There is no mechanism to do that and it’s hard to create these workarounds. It gives people anxiety. Communication is also very hard. We use different languages and how people approach problems, and we may bring something specific.”

• “Talking about scale at work — it’s exciting and exhausting.”

• “Art and health is something new in my country. First thing was to convince people in the health sector to embrace it. There is no experience in bringing interdisciplinary experience. My background was dance and arts. And it was me jumping three steps ahead. Had to set up panels with the arts, academic institutions and health institutions to get on the same ground. It took me three years.”

• “I think I’m always expanding my career. When the student is ready, the teacher will appear. I can imagine delving in one area, another one will open up. Like behavioral economics. I’m suddenly really interested in that field and better understanding why people do what they do.”

• “The Fellowship has helped me to think of ways to share my analysis through storytelling. It’s hard to do at work, but I’m practicing and tweaking to apply. I reached out to one of the futurists in Thailand, and he also provided examples about how to creatively bring people together through evidence.”

• “I come from a very traditional and religious family. My sister is also a doctor in pathology. It’s very hard to talk about and I try to get my sister involved, and she’s one of the youth I had to change indirectly. No one in my family does this or understands.”

• “After the Fellowship, I have a more collaborative spirit. I have really good friends here, but the Fellow experience is totally different. I still have to manage a lot of critical problems in my country and the public system, like there are not enough resources for patients or medication, and I’m often alone. I have found my co-Fellows are inspiring and the kindest people I know and they share their knowledge and tools, and that’s helped me to push through.”

• “I’m not sure if I was always like that: open and vulnerable to collaborations. I probably learned it in school. I’m also an executive, I like to do things quickly and quickly. But collaborations move slowly and it’s not just about you — that requires a lot of flexibility because it means the structures.”

• “I have an intense curiosity about a lot of things and seek different experiences to fuel that need for new and different things. I go to the same cafe and order a different coffee. I’m always seeking variety and that comes from curiosity and relationships and connection to places. It’s what drives me as a leader and a desire to play a role in enabling community success rather than buying a bigger house.”

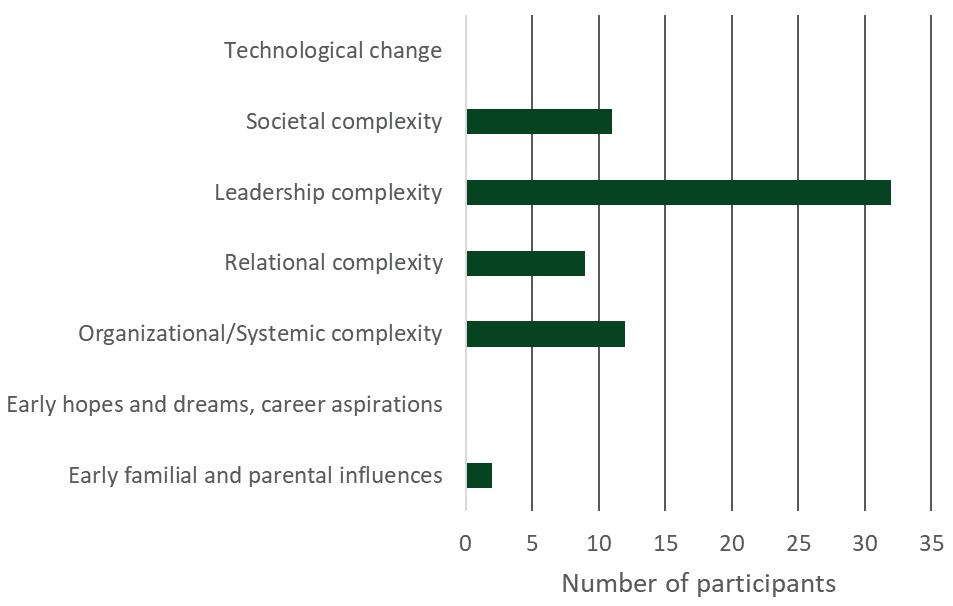

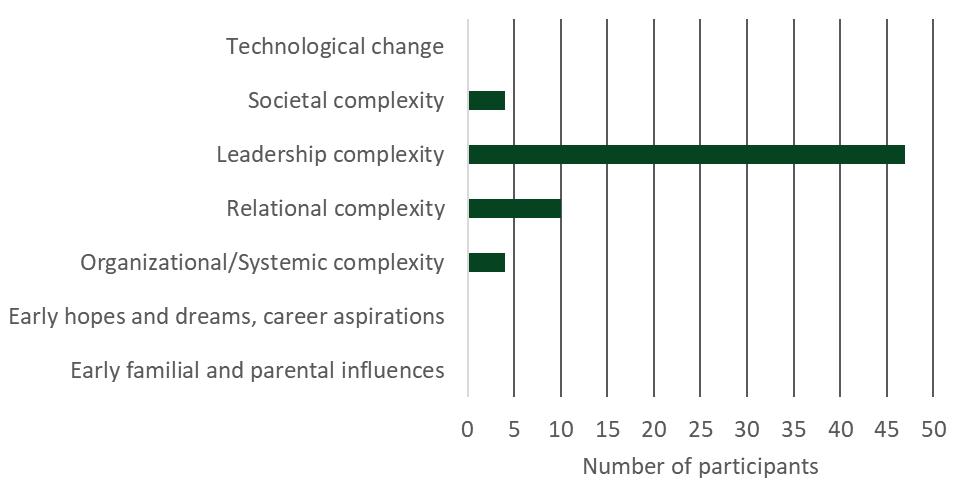

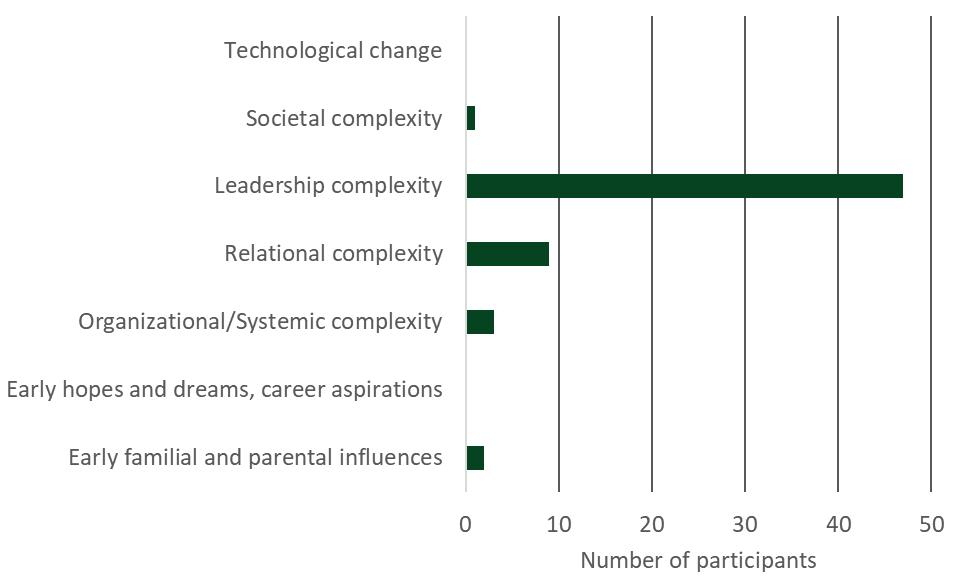

When considering the dominant intersecting trend of how Fellows view and navigate complexity, in relation to the pressure points discussed above, I found that most Fellows’ openended responses addressed the topic of navigating leadership complexity, followed by answers about organizational, institutional or systemic complexity and answers about societal complexity. While many Fellows had contextual units touching on early hopes and dreams and early familial influences, they were very rarely the dominant types of examples used in the answers. Technological change topics were very rare and were never the dominant intersecting trend in an answer.

Q8. Please provide specific examples of activities that you do for each leadership practice, dominant intersecting trends

Fellows said, for instance (by category):

Early familial and parental influences:

● “My Dad’s generation has done the same job for more than 50 years and that is very respectable, but I never saw myself doing the same job or being in the same place for more than five years. I think my philosophy [is] you only live once, there is so much to see and why limit yourself. I was always very curious since I was a child and my mom always had high expectations of me, like all moms. Wanted to make her proud.”

● “When I was five years old we moved to Brazil and we didn’t speak any Portuguese. Those months of navigating without language, I had to project receptiveness to people even if I could not understand. It got me to appreciate bridging and how to navigate systems that don’t reward approaches to the heart, human to human.”

Early hopes and dreams, career aspirations:

● “My background is marketing and sponsorship in the media and a large bank. I’ve also had a couple of other businesses before deciding to find purposeful work and giving back to the community. In my country we have a limited view on education for Indigenous community. That is a catalyst for me because I wanted to connect more with what I love more about my countries.”

● “I’ve always had a strong focus on learning. I did the Foreign Services early on and then got my master’s and took short courses to help with financial training and also took statistics. I’ve also done a pottery course and have been doing a public speaking course . . . podcasting course.”

● “I founded an org when I was in my early 20s. I felt very young and even back then it was purely passion driven to address the growing crisis. That’s what inspired me to create it. When I found it, I didn’t have money and we threw it all together.”

Organizational, institutional or systemic complexity:

● “My challenge right now is finding the balance of how to move the work as an individual and organizations, because we are volunteer-based organizations so we have to make sure everyone is on the same page and are interconnected and interdependent and have integrated values with ourselves and organizations.”

● “I only appeal to others about a dream of the future, to people I feel are ready to hear it. Because some people who are very technical, they can talk about the big picture, but they often also don’t have enough strategy to make it happen. When I talk about the big picture or about the future, I need to come up with a strategy.”

Relational complexity:

● “I spend time listening to the needs and concerns of a variety of stakeholders and thankfully I’m a good listener. So, my work is about trying to bring the visions of communities and local government together.”

● “I’m trying to bring a collective of individual organizations together. We’re trying to be cooperative, but we still have to build trust among all the groups.”

Leadership complexity:

● “I have an intense curiosity about a lot of things and seek different experiences to fuel that need for new and different things. I’m always seeking variety and that comes from curiosity and relationships and connection to places. It’s what drives me as a leader and a desire to play a role in enabling community success rather than buying a bigger house.”

● “I’ve been doing this work now for 18 years. And I see the value of my work beyond the grant cycle and what I’m expected to deliver as impact. I work at an NGO, but in the end I am doing this work so that some people’s lives will change.”

● “I started my nonprofit, but from day one I’ve been thinking about how to create a framework that the people after me can pick up on. I don’t really see myself as a founder and have had to get a leadership coach to help me.”

Societal complexity:

● “I recently had to run a meeting where I had to engage university management in discussions on gender and sexuality diversity.”

● “We are challenging the narrative and trying to innovate within the limits of the law, trying to influence the behaviors of service providers, community and children. Trying to show what a successful progressive government is.”

● “Things are risky for activists in Brazil, [and] work now is full time on making sure the president is not reelected.”

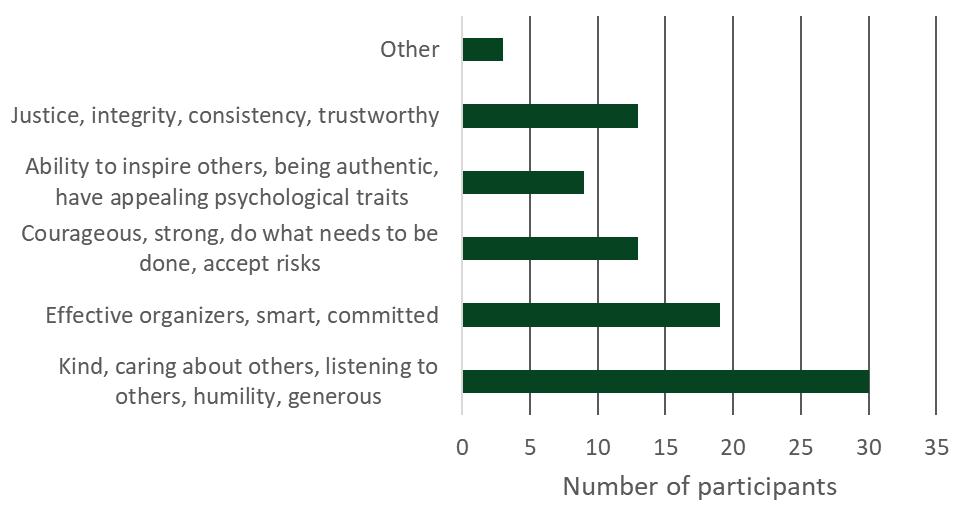

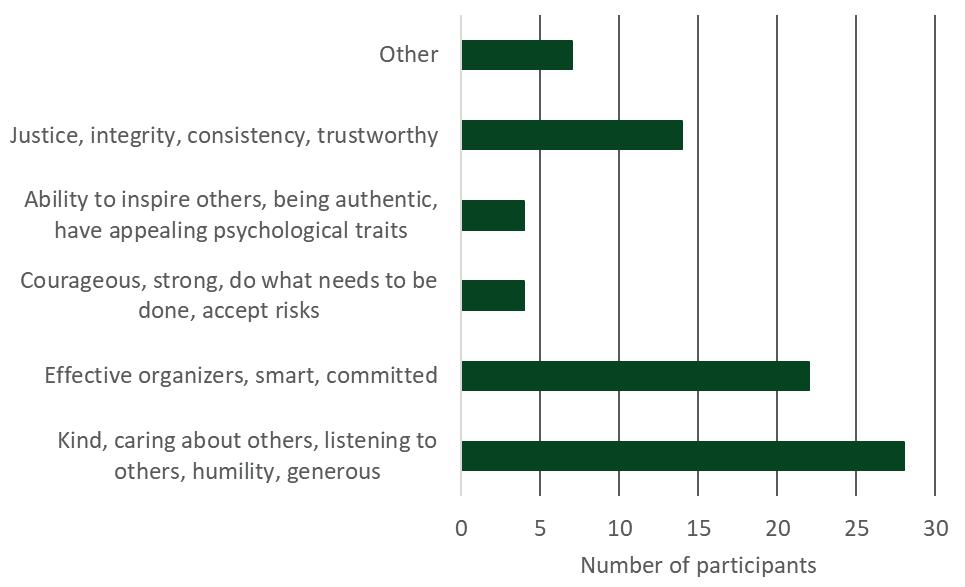

Question ten (Q10) is an open-ended question inviting Fellows to reflect on what leadership practices they most admire in others. Using the topic-based coding scheme, participants most often listed traits such as kindness, caring about and listening to others, humility and generosity. The second-most-common type of answer emphasized leaders being effective, smart and committed.

Q10. What leadership practices do you most admire in others? Topics

Sample answers include:

Kind, caring of others, listening to others, humility and generosity:

• “Humility, listening, compassion.”

• “Honesty, kindness and respect.”

• “Building up capacity and mentoring; being open to different perspectives.”

Effective organizers, smart and committed:

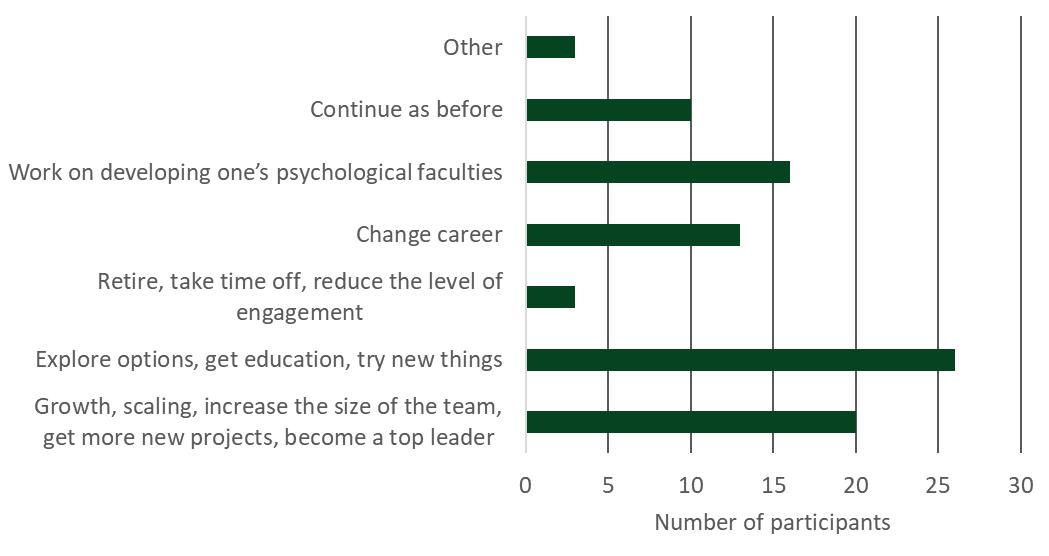

● “Commitment to action from seeing environmental activists. Would let things slide and could see the long term; executive director of this org: don’t sweat the small stuff.”