4 minute read

Telling Stories That Matter

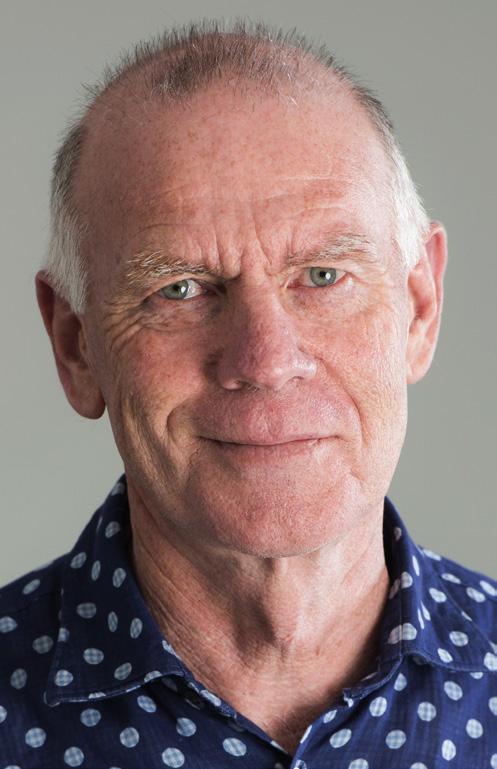

Evangelina Telfar talked to playwright Gary Henderson about what he learned in the process of adapting David Galler’s memoir and why this story matters.

In this piece you integrate What do you think are some of the differences between the book and this play?

The book is structured very differently. It’s not chronological. All the chapters are about a different organ of the body. David brings together stories of his experience of dealing with people’s suffering from some complaint that affects that organ. There was some sense of bringing that poetry into the play, but I haven’t really done it. I’ve tried to do it visually with images of X rays and things like that.

The whole book is written after his mother’s death but the whole last chapter is about his mother’s life.

The book starts with his father’s death, so I decided in my timeline it would be the space between his father’s and mother’s death.

How long have you been working on adapting Things That Matter and is it any different to the time it takes you to write an original work?

I’m just a really slow worker and I procrastinate. Sometimes it’s that fear about how you daydream how wonderful something is going to be but there comes a moment when you have to do it. The longer you delay doing it, the longer you can daydream about how wonderful it is because it doesn’t exist.

There were times when I wouldn’t work on it for a few months, but the deadlines helped. I always wish I was more efficient. In the end, I just think this is how I work.

What has been rewarding about adapting this book for the stage for you as a writer?

The things that it’s forced me to think about personally and look at in my own life. It was rewarding to me to delve into this because I read a lot and some of the issues I’m still grappling with. Just the things I had to confront and change the way I behave and think. And around the ideas around decolonisation.

I think it’s what white people have to do. You can’t just back away from the space because the space is not neutral. You actually have to do something. It’s made me say to myself, what am I going to do? What am I going to do in my life to decolonise New Zealand?

How have you made this memoir into a theatrical experience through script?

I had a particular vision for how I wanted it to look on stage because of the treatment of time. Raf just moves from one reality to another. Little things, like he talks to his father in front of Carol who can’t see him but then Carol gives him a bottle of wine to walk over to his parent’s table. Time is not a constraint.

I wanted you to be able to see his mother sitting at the table having a cigarette while there’s a medical scene going on over here and when he was at his parent’s place, I wanted you to be able to see the patients in the gloom behind him. So, none of those worlds disappeared. Everything is always happening.

What parts of the story did you fictionalise?

The medical staff come from Chris’ story because David says who is standing around Chris. He names the roles. There’s an emergency department nurse, another emergency doctor, a senior nurse taking notes and there was another doctor doing something. So, I said those can be the people going through the story. And so, I invented Dev, Edie, Ana and Carol.

I invented the Nagels. David talked about his childhood when there were these parties full of mad eastern European immigrants. He remembered they’d be lots of smoke, wine, and great coffee cakes and how it was wonderful. He didn’t name anyone, and he didn’t say anything specific about what happened. So, I just found an attitude for them and somehow, they could drive the story forward.

Do you think adapting is harder than writing an original work?

I don’t think the actual job is more difficult, it’s just a different set of responsibilities that you acutely feel. I was always against adapting because my theory was always why would you waste your limited creative life reworking someone else’s work of art instead of bringing something new into the world. Until I had a few encounters that made me realise that a new adaptation is a new work of art. It is not the book transposed onto the stage.

What was the workshopping process like considering that this is based on real people and real events?

It was workshopped as if it was complete fiction. Some people did a huge amount of research. The actors all played their roles as fictional characters and they only brought to it what was in the script and what the script demanded of them. So, they weren’t saying “yes but she was actually older than that and she wouldn’t do that”. That’s the character in play and that’s what you’re playing. They were really good, and the workshops were amazing.

Why do you think this story needs to be told now?

Lots of reasons. For a start, the racism. I’m starting to see it everywhere; I don’t experience it of course. I’m not a victim, I’m a colonizer. I want to be able to stand up in front of an Auckland Theatre Company audience and refer to them as white people. Not New Zealanders. I can say I’m Pakeha and that all sounds very woke but I’m a white person and I’ve benefited from colonization. In fact, the only reason I probably have a voice is because of colonization. If I was female and brown, I wouldn’t have said a word. Having said all that, the last thing I want to be is a white saviour.

It’s about someone seeing a problem that’s affecting a section of society and thinking that’s not fair and doesn’t need to be happening. I think it’s important because so much of the illness in our society is preventable. There's that piece in the play where Rafal said, ‘you go and look at our emergency department or our ICU, it’s not a failure of the health system, it is a failure of everything that’s gone before. It’s a failure in society: leaky homes, bad food etc.’ That’s what puts people there and none of them need to be there. And they go in there and they die.

A lot of themes in it are timeless, especially the need for compassion. I would frankly like to live in a world of those sorts of people.