10 minute read

Hang on to your deerstalker

Bob Damper is an enthusiastic devotee of the famous Dursley Pedersen bicycle – a relic of a bygone age, perhaps, but still a remarkable feat of inventive engineering. Hampshire-based Bob describes the history of the iconic machine – and explains how he found himself on a personal pilgrimage in April this year, dressed in Edwardian gentleman’s attire, riding a 111 year old bike – and trying to secure his deerstalker hat on the highest, windiest hill in the Cotswolds…

Hang on to your deerstalker… it’s going to be an historic ride

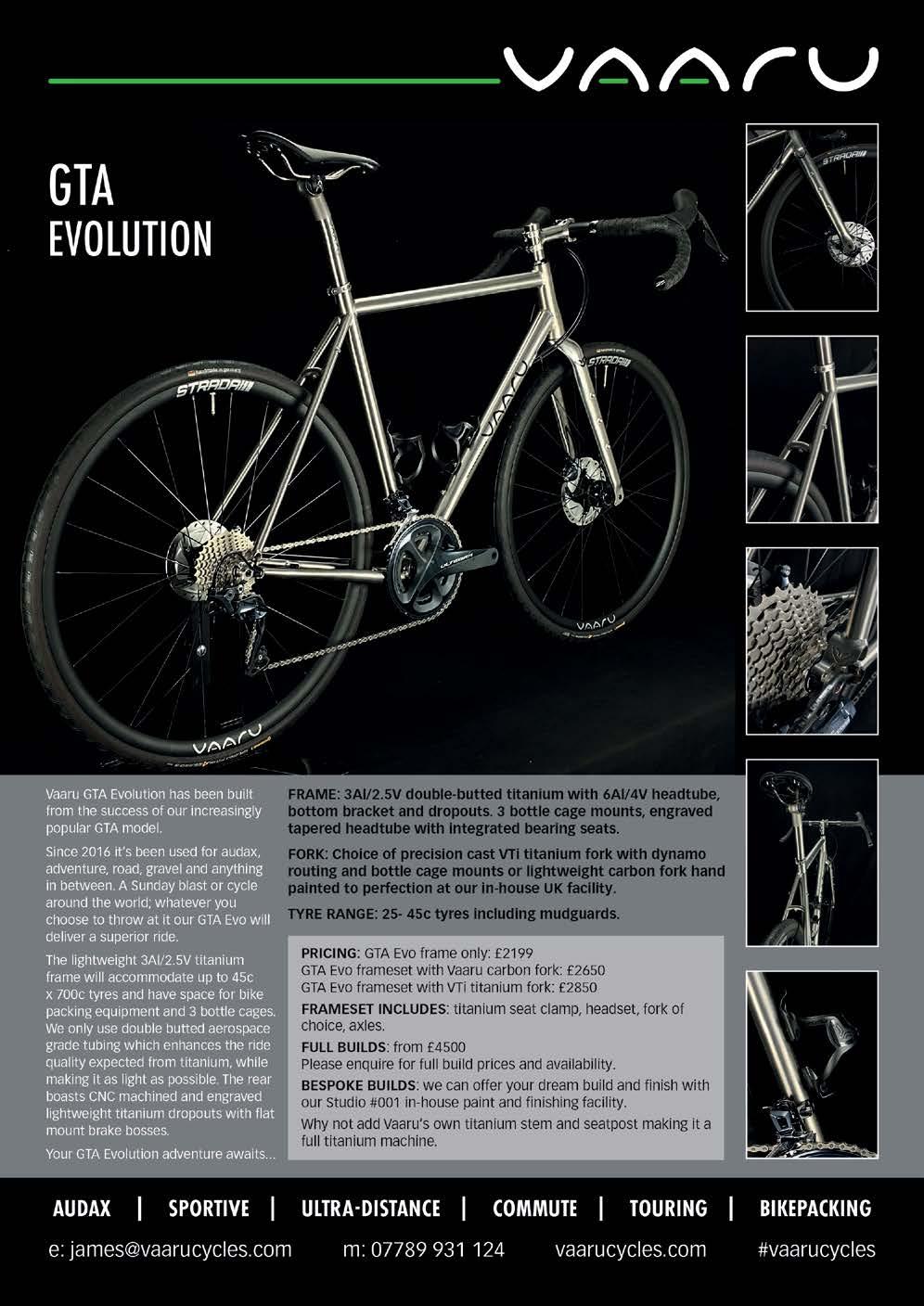

Advertisement

EVERY NOW AND AGAIN, the history of cycle design and cycling takes a dramatic turn away from established orthodoxy. Sometimes, as when the front-driver high-wheel “ordinary” gave way to the rear-driven safety bicycle in the late 1880s, this dramatic turn marks a permanent, revolutionary change in cycle technology, never to be reversed.

At other times, the new design is found wanting in some respect and consequently has a relatively short life as a commercial offering or develops into a niche product – often with a fiercely loyal following, as with Alex Moulton’s smallwheel design of the 1960s featuring its then unique suspension frame.

One of the most interesting turns was the highly distinctive machine designed by Danish inventor Mikael Pedersen (1855-1929) towards the end of the 19th century. By 1889, Mikael was living in the small Gloucestershire town of Dursley where he was employed as a consultant to R.A. Lister engineering company. Pedersen started to give increased attention to the further development of the unusual cycle design he’d come up with before leaving Denmark.

Pedersen had found the conventional bicycle saddle, rigidly attached to the machine, uncomfortable. In fact, as a highly individualistic and opinionated man, it is fair to say that it offended deeply his sense of engineering propriety. To his mind, a cyclist should be mounted on a much more forgiving attachment; one capable of moving flexibly with the rider, more akin to a hammock than a saddle.

The strikingly different frame geometry of the Pedersen bicycle – quite unlike anything else on the market – was designed to be both light and strong, but just as importantly, to accommodate the woven silk hammock-saddle that he favoured.

The strength and lightness of the frame were achieved by the use of thin, cross-braced steel tubes (specially supplied by Accles & Pollock of Birmingham, who later produced the highly regarded Kromo frame tubing) arranged in what Pedersen called a “cantilever” design. This is actually a misnomer, although the frame did have a more than passing resemblance to the Forth Rail Bridge, which is a true cantilever design.

Mikael formed the Dursley Pedersen Cycle Company in 1899 to market this unusual machine. The company also made and sold early 2- and 3-speed hub gears built to his design. These operated on a countershaft principle, unlike the contemporary competitor products of the Sturmey-Archer company in Nottingham, which used epicyclic (planetary) gearing.

The Dursley-Pedersen machine enjoyed some modest commercial success, but construction costs for the intricate “cantilever” frame were high and it was accordingly an expensive machine, well beyond the pocket of the ordinary working man of the time. There were also production and reliability problems with the friction clutch used in the early hub gears.

The combination of high production costs and selling price plus sporadic delivery issues (particularly with the hub gear) affected profitability to the extent that the company was wound up in 1905 and taken over by R.A. Lister, which continued production of the DursleyPedersen bicycle until around 1917.

In more recent years the design has been revived by various makers in Denmark, England and Germany so that it is now possible to have a more modern Pedersen with up-to-date componentry.

This quirky machine has long had a devoted following of enthusiasts. Since 2017, I’ve been the proud owner of a very fine 1910 (or possibly 1911) DP equipped with Pedersen 3-speed hub gear. In April 2022, Ben Amor of the Veteran-Cycle Club organised a “Pedersen Pilgrimage” for both original and more modern machines, based in Gloucestershire. This excellent event was attended by more than 40 devotees and their mounts.

It featured a short ride from the meeting point in Slimbridge, to Dursley on the Saturday morning, where we were met by the deputy mayor, local media and a throng of bemused townsfolk. A tour of sites associated with Mikael Pedersen and the cycle works was followed by an excellent ploughman’s lunch, and a return to Slimbridge for tea.

On the Sunday morning, we took our DPs for a most enjoyable spin around the

My 1910 Dursley-Pedersen at Cleeve Cloud summit

At 330 metres (1080 feet), Cleeve Cloud is the highest point in Gloucestershire and the highest point in the Cotswolds

lovely Vale of Berkeley in wonderful spring sunshine, returning to Berkeley for lunch. I’d decided to stay on in Berkeley for another night because I had something rather special in mind for the Monday morning.

As an OCD CycloClimbing obsessive, I am always on the lookout for possible claims and had spotted that my base for the weekend at the Malthouse Inn in Berkeley was but a short drive from Cleeve Cloud on the Cotswold Edge limestone escarpment above Cheltenham.

At 330 metres (1,080 feet), Cleeve Cloud is the highest point on the Cotswold Hills. As such, it represents a very valid OCD claim, provided it is reached after at least 100 metres of ascent. Furthermore, Cleeve Cloud was my first ever OCD claim on 11 April 1963 and I could not resist the lure of climbing it again exactly 59 years to the very day on 11 April 2022. So after a good full English breakfast, I drove along the A38, M5 and A40 through Cheltenham to park in the pretty and peaceful little village of Whittington, lying secluded below the Cotswold Edge.

I soon had the DP out of the back of the car and was on the road and climbing gently from a starting elevation of 185 metres on a very pleasant lane. After the best part of a mile in a westerly direction, I took a right turn to the north on a narrow lane with indifferent surface. The climb became steeper, but this was compensated by a very strong southerly tail wind. The wind was such a help that I managed to ride most of the way to the point where the road ends at Cleeve Common without dismounting.

One of the quirks of the Pedersen 3-speed gear is that it has enormous steps of 50 per cent between gears, as opposed to the ubiquitous Sturmey-Archer AW with its 25 per cent drop from normal to low and 33 per cent step up from normal to high. This means that my DP has a bottom gear of 44 inches rather than the 50 inches I would have with a Sturmey-Archer hub for the same direct drive of 66 inches. Along with the tail wind, this made climbing relatively easy, but I’m acutely aware that my Pedersen gear is well over 100 years old and largely irreplaceable, so I am reluctant to give it a lot of stick when hill-climbing. Much more prudent to get off and walk when the going gets tough; that way I get to conserve an historic working machine to ride another day.

It was a bit of a struggle to get my bike through the kissing gate by the three radio masts (which form a prominent landmark for miles around) and on to the open common. Strictly, this is just a footpath across open access land and so provision for cycles has not been a consideration. Once on the common, it was an easy (if illegal) ride to the trig point at the summit. The recent Glover Review of protected landscapes recommended granting higher rights to riders of horses and cycles on open access land, but the early indications are that this is one of many sensible recommendations that the government will conveniently ignore.

Arriving at the trig point, I mused on the fact that this was my first ever OCD claim on a pre-WW1 bike, so that it was really something of an occasion. The terrain is rather flat around the trig point; consequently, this is not the best viewpoint from the hill. The view is considerably better closer to the Edge itself, with the Malvern Hills and Black Mountains in Wales prominent across the Severn Valley, and Exmoor just about visible far away to the south west. The wind was pretty fierce, strong enough to blow off my period deerstalker hat and making it necessary to tie it down by the ear flaps – for the first time in its long life.

As it was decidedly cold at this altitude, I did not tarry too long but soon set off across the open common to join the bridleway running eastwards to Wontley Farm. The long dry spell we enjoyed in early 2022 meant that the bridleway was in good condition and easily rideable, if a little rough and stony on the descent to the farm. Here I turned south on another excellent bridleway to rejoin the tarmac road at West Down.

When I acquired the Dursley-Pedersen in 2017, the brakes were quite awful –

The hugely complicated braking on the Dursley-Pedersen The Pedersen 3-speed hub gear

essentially ineffective if travelling downhill at anything more than about 12 miles an hour. The brakes are a bit of a work of art, with inverted (bar-end) levers operating a cable hidden inside the handlebars to emerge through a tiny tube that interfaces with a rod actuating a stirrup mechanism. The rear brake is especially exotic with a complicated linkage mechanism between the handlebars and rear wheel.

So bad were the brakes that, at first, I found it necessary to walk down any kind of serious hill. As you can imagine, this rather limited my enjoyment of riding the DP in hilly country, so I tried many and various things to improve the braking. After a great deal of trial and error, I found some brake blocks that not only fitted the original brake shoes, but also seemed to work tolerably well on the DP’s steel Westwood rims. But the real breakthrough came when I discovered that the hollow part of the stirrup, into which the interfacing rod slides to give adjustment, was caked with some 100 years’ worth of corrosion and muck. A thorough clean out meant that, for the first time in many years, it was now possible to adjust the brakes to give a semblance of efficient stopping power.

This was just as well, as it was quite a drop off the Cotswold Edge at this point, while not exactly alpine is enough to require caution at the steeper (and inevitably potholed) sections. Just over 100 metres of descent saw me back at Whittington after a thoroughly enjoyable 75 minute, eight mile ride, of which just over a mile and a half was easily rideable roughstuff.

As Audaxers, we all know the pleasure to be had from setting and meeting personal challenges, but this does not always have to mean long days (and sometimes nights) in the saddle, as this little expedition showed. What a joy it had been to combine my three loves of cyclo-climbing, veteran cycles and roughstuff, and who cares if it was only eight miles.

My 1910 DP at Mikael’s graveside during the Veteran-Cycle Club’s “Pedersen Pilgrimage” in April 2022

BOB DAMPER

Seventy-three year old Bob, from Chandler’s Ford, Hampshire, joined CTC in 1960, and is now a life member. He’s also a vice president of the Veteran-Cycle Club and has been a member of the Rough-Stuff Fellowship, Sotonia CC, and the Moulton Bicycle Club. He completed PBP in 1987, but admits to a heroic failure, aged 71, in 2019 after 1,030km with a foot injury due to pedal pressure. He suffered a similar fate on LEL in 2017, when a pedal axle broke in the middle of the night after 1,100km. He has completed a Super Randoneur several times. For those interested in the Pedersen Dursley story, Bob points readers to the book, “Mr Pedersen: A Man of Genius” by David Evans, published by Tempus Publishing of Stroud.