23 minute read

Nobody’s Thule

Ancient cartographers knew of the existence of an island in the cold, far north – and on their maps, surrounded by dragons and sea monsters, they wrote the word “Thule” – literally meaning a place beyond the borders of the known world. London-based Canadian Mark Kowalski, right, didn’t know much about Iceland before pandemic travel restrictions forced him to pick the place for a bike-packing tour. What ensued was the start of a love affair with a strange, alien landscape. This is his story of a remarkable cycling adventure…

Nobody’s

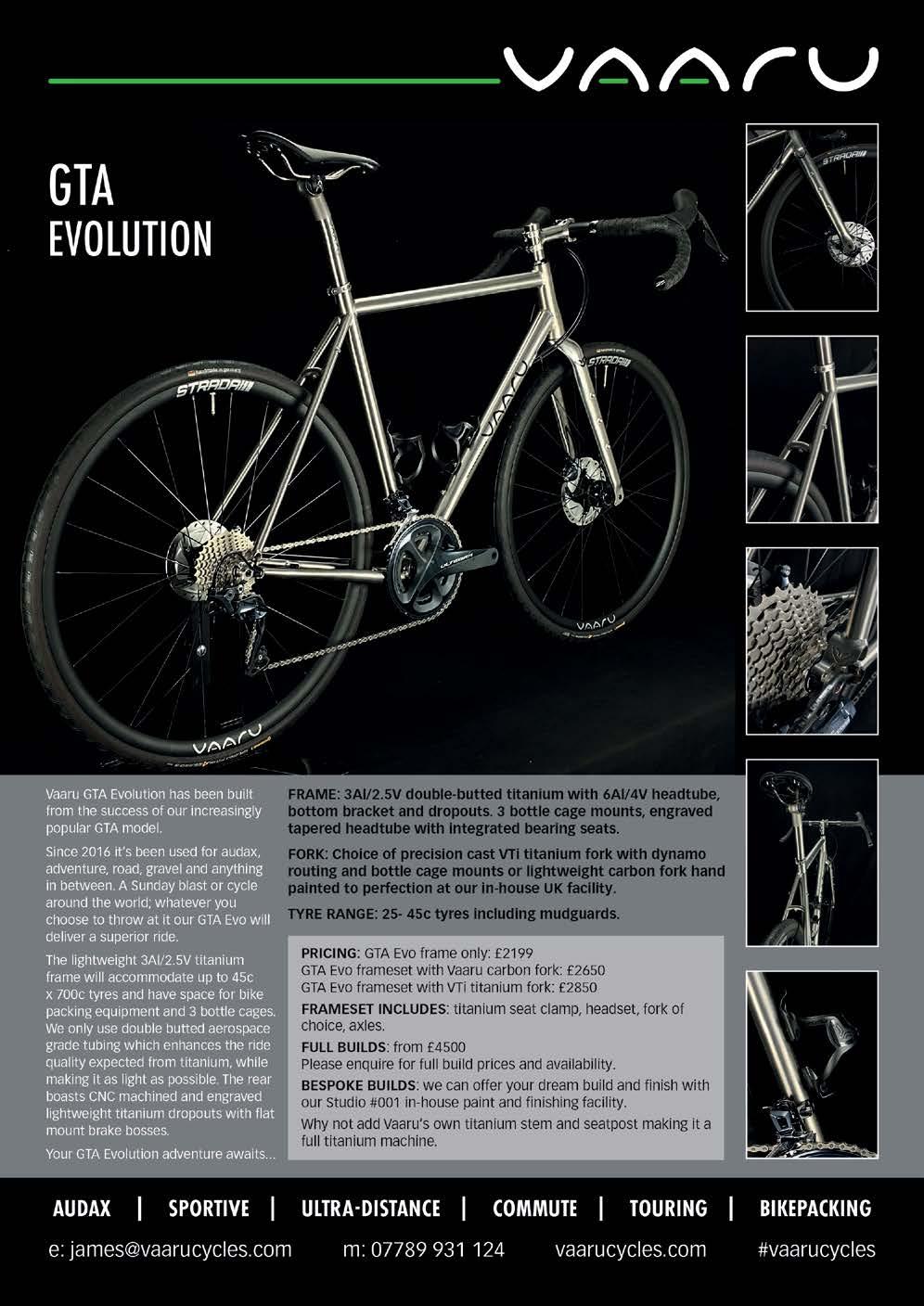

Advertisement

Enchanted by a land of fire and ice at the edge of the world

I BOUGHT MY TICKET TO REYKJAVIK

just three days before my flight, but Iceland wasn’t a spontaneous choice for a cycling tour. In summer 2021 it was one of the few countries on the travel green list. In hindsight, it was the perfect destination. The remote island, just below the Arctic Circle, is a three-hour flight from London. Who could say no to that?

Reykjavík had plenty of traffic, but more bike lanes than London, and once beyond the capital, drivers become patient and courteous. Campsites are plentiful, and most have showers, shelters, sockets, laundry, and don’t require reservations. A single pitch cost around £10. Of course, Iceland is expensive, but from a cyclist’s perspective you receive a seismic bang for your buck.

DAY ONE – REYKJAVIK

Looking out of the airport bus window as it carried me and my 1987 Raleigh Royal the 50 km to the first campsite, I thought we’d been dropped off on one of Jupiter’s moons. I’d be spending the next two weeks riding through a lunar landscape where geological activity was high.

Unlike Jupiter’s moons, Iceland has an established network of service stations where you can refuel on local lamb hot dogs (£2.75 each), and where water is so obviously clean and abundant it was not sold anywhere.

Following the coastal path network, I snuck out of Reykjavík, avoiding its busy arterials, before turning inland where I discovered lush fields of the controversially invasive, but wonderfully pretty, purple Alaskan Lupin, growing everywhere. The Lupins were introduced as a soil preserver, to combat centuries of extreme soil erosion. The locals either love them or hate them.

It was soon obvious that I couldn’t pronounce anything. The Hvalfjörður Tunnel runs for six kilometres, 165 m below sea level. Bicycles aren’t allowed to use it. Cyclists get the pleasure of a 50 km scenic route into the whale fjord. A total of three cars passed me the entire way as I skirted its coastal mountains. There were remains of British and American wartime naval bases, built after the Allies invaded Iceland to defend transatlantic shipping lanes.

The American base had been converted into a whaling station, Iceland’s last remaining. As recently as 2019, whaling was carried on here, but due to

Mark Kowalski

Mark fell in love with long-distance cycling after touring coast-to-coast across his native Canada in 2017. On returning to London, where he lives and works, he Googled “long-distance UK cycling events” to find a way to continue discovering new places by bike. He’s been a member of Audax UK ever since. Mark posts video stories of his cycling adventures on instagram.com/kowalifornication, where you will also find a three-part video series of his 2021 trip to Iceland.

Thule

Receding outlet glacier flowing down from Vatnajökull

the pandemic and the resulting drop in tourism, ceased operations. It’s uncertain if commercial whaling will resume – fingers crossed it doesn't.

After battling the wind while crossing Iceland’s second longest bridge into Borgarnes, traffic reduced significantly, and an accommodating tailwind whizzed me 100km north in four hours. I arrived at the peaceful Sæberg Campsite in time and with sufficient 4G, to catch most of England’s victory over Denmark in the Euros. Just before midnight I took a lonesome dip in the camp’s thermal pool, and ended the day watching the midnight sun dip across Hrútafjörður.

DAY TWO – 217KM NORTH-EAST TO AKUREYRI

Two ascents divided this day, climbing 350m and 530m, but they were gratifying. The second climb was up through a gorge beside a raging glacial blue river, cutting its way down through the rocky cliffs. I arrived in Akureyri, Iceland’s “Capital of the North”, nestled at the base of a mountain on the edge of a fjord, Eyjafjörður, is a cosy historic town with shops, cafes and food stalls, all constructed with brightly painted sheetmetal and dominated by the stoic Lutheran church. The mood felt alpine.

After setting up at the city campsite, I explored. I struck up a conversation with Lello, the owner of an Italian pasta stall, who treated me to a sweet antipasti of sfogliatella filled with a cinnamon and ricotta icing. Later on I checked in at a local music venue. The doorman waved me through without charge as the gig was winding down. The headline act seemed to be Iceland’s version of Jack Black. He shared funny stories and songs in both Icelandic and English to a very cheery local crowd.

DAY THREE – 100KM NORTH-EAST TO HÚSAVÍK

Húsavík was a 75km detour, but I was keen to see the little fishing village where Will Ferrell’s 2020 Eurovision Song Contest was filmed. Highlights included befriending the employees of the very well-curated whale museum, and taking a carbon-neutral schooner out into a blue-skied Skjálfandi Bay, where we came across a humpback whale rolling around.

DAY FOUR – 56KM SOUTH-EAST TO MÝVATN

Departing late after the whale-watching tour, I was alone again, finally catching a tailwind. I passed through the Holasandur

The alpine town of Akureyri on day two The second summit of day two with lenticular cap cloud in the background

Húsavík fishing village with whale-friendly electric-powered schooner Ópal

(“the Hills of Sand”), a man-made desert caused by 300 years of overgrazing and soil erosion. There is an ongoing project, funded by taxes on supermarket shopping bags, to plant lupins here to recover soil.

As the evening turned golden I rode across the remnants of a vast volcanic eruption 2,300 years ago. The grass was recovering, and it breathed life. Just outside Mývatn, a van whooshed by, the smiling face of Nicole hanging out the window, waving. She, her boyfriend and I had met on the schooner. Iceland being the small place that it is, we ended up finding each other in the next campsite and sharing tea and the one beer I had on me.

DAY FIVE – 120KM SOUTH-EAST

Mývatn translates to “Midge Lake”, but really they should just call northern Iceland “Midge Island”. I was told they didn’t bite – but that was a lie. My ears were soon riddled with bites, becoming inflamed and infected. Midges and my ears aside, the Mývatn area is stunning. High in biology, and a geological hot zone, I discovered “pseudo-craters”, formed when lava flowed over moist bogs, causing giant steam explosions, hot lagoons in underground lava caves, bubbling mud pools, sulfuric fumaroles, and a rocky landscape that seemed to have simply boiled, leaving behind fissured domes.

My favourite part of the hot zone was seeing Iceland’s first, and smallest, geothermal power plant. There was no one around, so I rode gingerly up to it and admired the steaming pipes feeding and venting hot boiling water, energised by the earth’s core.

The temperature hit 28 degrees as I crossed Iceland’s northern desert, fighting headwinds but beaming from ear to ear. A desolate lunar world, with flat-topped, steep-sided and snow-capped Herðubreið (“the Queen of the Mountains”) to the south. This rare mountain type is known as a tuya, formed when a volcano punctured a hole in the then-present 1.5km thick ice sheet – its icy embrace forcing the lava to cool upwards well over a kilometre into the sky.

My only stop was a restaurant made of grass turf in the middle of nowhere, on the edge of Iceland’s most elevated settlement, Möðrudalur (469m). Forests once covered 30 per cent of the island. It’s now only two per cent, thanks to the Norse settlers cutting down everything for grazing and building materials. I ordered

Sustainability Iceland style makes Mark happy

the traditional lamb stew and a deep fried cake ball which pairs well with coffee. They are actually called ástarpungar, which translates as “love bags”. Yup.

I pushed onwards into headwinds hoping to make it to Egilsstaðir in time for the Euro final, but it was not meant to be. Thankfully, I happened upon a quirky reindeer farm campsite and hotel at the side of the road. The kind receptionist said she would show the game on the restaurant’s TV. Unfortunately, the game was on the one channel the hotel didn’t have (there are two channels in Iceland). Undeterred, I teamed up with a Kiwi from London and we drank Viking beer and ate reindeer burgers while watching the nail-biting game on his laptop.

DAY SIX – 137KM SOUTH-EAST OVER THE ÖXI PASS TO THE EASTERN FJORDS

When I arrived at the gravel turn-off for road 939, which ascends up and over the Öxi Pass, two Hungarian riders who’d just completed it shared in broken English what I could expect. The one who couldn’t speak English simply smiled, kissed his fingers and flicked them into the air. Dangerousroads.org describes it as a road “not for sissies – where one mistake can have consequences.” I rolled my 28s on to the bouldered track.

Beyond the Öxi Pass are the Eastern Fjords. Once at the top, the track drops at 17 per cent as you descend 500m over eight kilometres on to black sand beaches. My rim brakes burned as I skidded down, pulling to the side to let vehicles pass, and stopping frequently to comprehend the scene. This world was alien. To my right, a ridgeline made of cascading basalt terraces rose up from the earth. Snowcapped mountains flanked my left, the fjords down in the middle. I was definitely not on planet Earth anymore.

Ástarpungar stop near Möðrudalur

Descending the Öxi Pass

DAY SEVEN – 106KM SOUTH-WEST TO HÖFN

In Djúpivogur I met Ben from Montana on his first cycling tour. With a strong south westerly discouraging me from pushing on into the night, we agreed to cycle to Höfn together in the morning. The continuing wind made it slow-going. The wind was easily ignored as we shared in both good conversation and awe at our surroundings, marvelling at another new and alien world we were discovering – eastern Iceland’s black volcanic beaches and scree mountains.

The dark and ominous mountains endemic to this stretch of coastline, with their cores made of solid gabbro and granophyre rock, give the appearance of jagged stone giants rising out of black sand pyramids – defences which make them impossible to climb.

This type of rock forms deep in the Earth’s ocean crust and geologists estimate this range rose up around 11 million years ago. Iceland as a landmass is one of the youngest on Earth, estimated to have risen from the ocean 16 to18 million years ago. There is evidence to suggest that the first settlers of Iceland made this coastline their home during the seventh century – monks from Ireland – some 200 years before the arrival of the Vikings in 874.

Before reaching Höfn, we spotted a gargantuan ice sheet on the horizon. Towering over and sweeping down towards the sea, it was one of 30 outlet glaciers flowing down from Vatnajökull – the largest ice cap by volume in Europe, covering an area of 8,200 sq km. With this behemoth on the horizon awaiting us the next day, we toasted our progress over an array of craft beers in town. Our schedules meant I had to depart solo in the morning.

DAY EIGHT – 136 KM SOUTH-WEST TO SKAFTAFELL

Leaving Höfn, the wind seemed to have lost track of me and I made the first 80km to the Glacier Lagoon in a joyful breeze. This was tourist territory; we all took selfies as the calving icebergs proceeded at a snail’s pace, until occasionally one was sucked out by the river and into the Atlantic, where they tumbled around in the surf, polished smooth, and then deposited back on to the black sand beaches, where they gradually melt, giving the area its name: Diamond Beach.

It is estimated that Iceland’s glaciers have lost around 32 per cent of their volume due to human activity since 1890. And the pace of loss is accelerating, with around half of this occurring in the last 20 years.

Upon leaving, the headwinds found

Fjarðarárgljúfur canyon; with paths now roped off after tourism increased 300 per cent following a Justin Beiber music video, with the influx damaging local vegetation Gabbro and granophyre mountains with Vestrahorn in the distance

me with a vengeance. It was a further 55km, uphill, where the next bend in the road seemed never to come, and where the ominous clouds weren’t quite sure whether they were going to unload their freezing rain. A cyclist’s and conservationist’s principle came to mind: keep pressing on and maintain a positive mind-set, or perish.

DAY NINE – 148KM SOUTH-WEST TO VÍK

At the day’s halfway point, visibility deteriorated with an influx of fog and a permeating rain. The endless lava fields closed in around me. I was warm and happy, but after about an hour completely soaked through. I had a tailwind, otherwise I may have had to take nonexistent shelter. I recalled my only chance of this being a toilet in the middle of nowhere with a slanted exterior wall. Though that would have probably been a mistake; with food and water but no soft ground to stake a tent, hypothermia would have quickly set in.

Vík is the most southerly outpost in Iceland and its warmest and wettest coastal settlement. The local beach is said to be one of the most beautiful on Earth, where Atlantic rollers batter against bluffs of rising basalt cliffs. Despite my visit in what is meant to be its warmest and driest month, it felt anything but. And regrettably, I did not think I had the right clothing, tyres or mental fortitude to make the hike out to see them.

DAY 10 – 177KM NORTH-WEST TO GULLFOSS

I awoke to more rain. A storm had come in overnight so I hung my tent in the laundry room and chatted with a group of Red Cross workers from Austria. The rain eventually stopped but it led to a late start. I didn’t set off until noon. With a strong south-westerly over my left shoulder, I altered my plan, aiming to make it to Gullfoss on the Golden Circle. My enemy became my friend, and I sailed north. Traffic picked up as I came within range of Reykjavík. Despite being late leaving camp, I couldn’t help stopping at Skogafoss and Seljalandsfoss for some excellent waterfall sightseeing.

I often hyperbolise that a headwind can be the worst feeling in the world, both physically and psychologically. However, a tailwind brings the opposite feelings. It energises you. I think it’s the closest thing to flying. The air turns silent as your bike matches the speed of the wind. You can relax and turn your full attention to the world around you. For the next two hours it was just me – a secret back entrance into the Golden Circle.

With five kilometres to go the pavement ended and a construction zone began. I bumped and bobbled my way across cobbles of all shapes and sizes, rocked up to the campsite and headed straight to the shower block.

On entering the bar, a sheep dog greeted me, and people turned to see who’d come in. I introduced myself as someone in need of beer and pizza. The bartender told me the kitchen had shut an hour ago. Beer would suffice. I plopped myself down at the end of the bar and greeted the others.

The patrons were all local farmers and inevitably the conversation turned to the Lycra-clad cyclist among them who had apparently not known that they had cars

Gullfoss. Sigríður Tómasdóttir threatened to throw herself in to protect this place

in Iceland for travelling great distances. A young couple slid their leftover pizza down to me. It’s hard to beat free pizza when the kitchen is closed and you’re half starving. Last orders rang out so I ordered a second pint with a round of shots for the company – Brennivín, Iceland’s national spirit. It went down smoothly and tasted quite nice.

DAY 11 – 81KM WEST TO THINGVELLIR

Next on my agenda was to visit the Great Geysir – the first geyser known to modern Europeans. It has in the past reached heights of up to 70 metres, and as high as 170 metres. In the last few years activity has ceased. You must either wait for an earthquakes to revive it, or be content with the 30 metre plumes of Strokkur, erupting every few minutes to its left. Geyser fields are extremely rare, located in only four places on the planet – Yellowstone, the Valley of Geysers in Russia, El Tatio in Chile, and here in Iceland.

Back on the road, I rolled at a leisurely pace to Thingvellir National Park where the park rangers guided me to a secret camping spot on the lake, for tents only. The rangers recommended I take the time to walk the rift canyon, the tourists having left for the day.

It’s hard to put the next scene into words. I’ve dreamed about tectonic plates since boyhood, but always struggled with the concept. How could continents really be surfing over a layer of lava, forcing the Rocky Mountains up a little higher, a little more each year? If you too find it hard to visualise the plates, you must visit Thingvellir.

I followed the forest trails until I stood between two great stone walls, stretching back behind and in front of me – like something the Mayans might have built. The western wall rose higher, and appeared almost to topple over me. I was standing on the edge of a retreating tectonic plate – the North American. To the east, the Thingvellir rift valley sinks into Lake Thingvallavatn, and on the horizon. the Eurasian Plate.

Thingvellir once served a great political purpose for the early peoples of Iceland, who would trek from all four corners to hear and enforce new laws. Like a sacrificial ceremony, women accused of infidelity were drowned, murderous men were beheaded, and supposed witches were burned.

Finding the campsite on the shore of Lake Thingvallavatn, I set my tent up next to the stone foundations of a turf-roofed hut. The 11pm sun still over the horizon gave ample light for a fly fisherman. Everything glistened.

DAY 12 – 78KM SOUTH TO HVERAGERÐI

I joined a snorkelling tour through the Silfra fissure. We spent most of the three hour tour being man-handled into dry suits, before plunging ourselves into the clearest water I’d have ever seen. The fissure is fed by spring water, filtered through porous lava rock far below us, having started its journey 30 to 100 years ago as meltwater from Langjökull, Iceland’s second largest glacier 50 km to the north.

We bobbed around in our buoyant suits, gargled astonished cries through our snorkels, while the constant current created by the percolating water below us pushed us through rocky crevasses. Below

us the walls disappear into an abyss. The only life one noted was the half dozen humans and an alien form of bright green algae which grew long stringy “troll hair” that waved to us in the current. I took a gulp – it was the best water I’ve ever tasted in my life.

I was told that the small road around the western side of Lake Thingvellir might or might not be gravel – but it would avoid the late afternoon traffic, so I chanced it. I had the road to myself – a wonderful unwinding ride along the water’s edge. After making my way around Thingvellir’s southwestern side I turned south to make a circle around the Grensdalur volcano region, my track for the day making a giant ‘S’ shape. For the last 11 km from Selfoss to Hveragerði I had no choice but to cling to the crumbling edge of Route 1.

In Hveragerði I headed straight for Ölverk – a geothermal-powered pizza place and pub. The place was rammed but I found a seat at the bar where I patiently waited for a waitress to find her breath. I ordered, and polished off, a spicy vegetarian pizza. Elva and Laufey, the brew master and pizza power couple, opened in 2017. I was so enthralled by the place, I cheekily asked Laufey if she had a spare staff hat. She gave me one, covered in a light dusting of flour, with the name “Cheesus” scribbled on the underside of the brim. Thank you Laufey, and Cheesus, for a great evening.

DAY 13 – 111KM SOUTH-WEST TO THE VOLCANO

The day began with another 10km of Route 1 traffic, this time with a bit more shoulder, but a small sacrifice to visit another bucket list destination – the Hellisheiði Power Station, the third largest geothermal power plant in the world. I took the back road in, getting to see the inner workings of the plant site. A zigzagging set of six giant pipes carrying boiling water led me down a mountain side. The steam, which turns turbines to generate electricity, is recondensed and carried to Reykjavík to provide its populace with hot water. Any waste hot water is then used to keep walkways clear of ice.

Leaving the powerplant I ascended a quiet road into a Martian landscape under a blue sky. I was surprised to find a set of ski lifts – and even more surprised to see the road ended there. I’d missed the turn off. Backtracking, I discovered why. The road was barricaded off. Google suggested the road was passable, but a new search of a translated site declared the road closed due to the risk of cars “rolling over with the associated risk of oil pollution”. Well, the road’s lunar surface suggested I might roll over but there was no risk of oil pollution, so I edged around the concrete barrier and wobbled my way down the track – singing the “Road to Nowhere” as I went. It would be 12km before I returned to the pavement – I wanted to kiss it.

On 19 March 2021, four months before my visit, an eruption shook the earth and a deep fissure cracked open along a nondescript hillside in the Fagradalsfjall region, just 50km from Reykjavík. Up from within the earth came gushing a continuous column of lava. I arrived at one of the impromptu car parks set up to cater to the thousands of tourists who, since the eruption, had come to trek up to the Fagradalsfjall Volcano. I noticed a Troll Expedition guide unloading his shuttle bus of visitors. I asked him what the conditions were like, should I be crazy enough to want to take my bicycle up with me. He responded with a firm: “Not possible”.

So I figured I would walk my bike up a bit, leave it somewhere before embarking on the major ascent. An elderly man stopped me to remark how he wished he’d brought his bike with him. He encouraged me. I said: “This bike? Up there?” He nodded. I began the ascent, a fully-loaded bike in tow.

As other hikers saw me they stopped in their tracks, mouths agape. I pushed and pulled my way up, two steps forward, one step back. What was that fool talking about? I was the fool of course, but I didn’t let it visibly stir me and I laughed and joked about the situation with those witnessing it.

I made it to the top of the first peak overlooking a lake of cooling black rock, with no lava river in sight. Dormant. I imagined the Reykjavík Evening News that night – “Man drags bicycle up volcano, sees nothing”. Exasperation fizzled into my head, the wind blew cold and fierce, and evening was approaching. I turned back, knowing I had a second chance to return in the morning when maybe Mother Nature would cooperate.

DAY 14 – 86KM NORTH-EAST TO REYKJAVÍK

As a touring cyclist I live by an irrational rule of never back-tracking. An exception could be made to see lava. I’d been texting back and forth with Montana Ben. He was spending his last day in Iceland and took a bus from Reykjavík to see the volcano. A French woman had been to the volcano the prior evening. I asked her if she had seen anything, as I hadn’t. Her eyes lit up. “Oui! C'était extrêmement magnifique!” I’d not hiked in far enough. Past the first peak, and then again over a second, lay the main event. I texted Ben saying I’d meet him at the base of the climb – where I’d leave my bike.

The morning brought a new weather front, and the peaks above us were shrouded in cloud. Ben arrived as part of a tour group, which I joined. The guides hoped the cloud would disperse by the time we took the longer way up around the back of the mountain. The cloud dispersed. And, lo and behold, there it was

Our second attempt at sighting the Fagradalsfjall volcano, sans bike, with Montana Ben

– sounding like an aircraft flying by, thrusting its engines as massive gobs belched high into the air, cascading down and frothing over the edge of the fissure.

A gushing river was flying down the hillside, splashing up into the air like white water through a canyon, before disappearing into a valley below, cooling into new black rock lakes. Ben and I made a run for it, hopping along the rocky path to make the most of it in the time given to us. We found some seats on boulders and settled in for the show.

Bright-eyed and high on life, Ben and I made our way back down the valley where I reunited with my bike. While I cycled my final leg back to Reykjavík he visited the Blue Lagoon. We arranged to go for a final beer that evening before he departed the next day.

Day 15 was my last full day in Iceland and I spent it on a walking tour of the city and trying on second-hand lamb’s wool sweaters, then falling into a panic because of leaving my return covid-testing arrangements to the last minute. As I walked on to the highway from the parking lot of the airport testing centre, ready to walk a few kilometres back in the rain to save the return taxi fare, a car pulled over. The driver, with his little daughter in the back, offered me a lift. “You looked like you needed a ride”, he said.