The Time of the Dinosaurs

Read the information on the squares carefully. Cut and paste the squares to your construction paper with the corresponding area.

Outside flap

FOLD ›

Inside flap

Paste the period information here

Paste the period information here

Paste the period information here

›

Write: Triassic Period

Write: Jurassic Period

Write: Cretaceous Period

The Jurassic Period began about 201 to 145 million years ago. During this period, dinosaurs coexisted with mammals. Large sauropods, like Brachiosaurus, thrived in this period. Brachiosaurus was a heavy, long-necked, herbivore that walked on four legs.

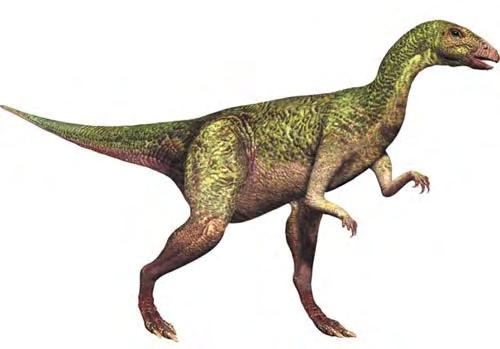

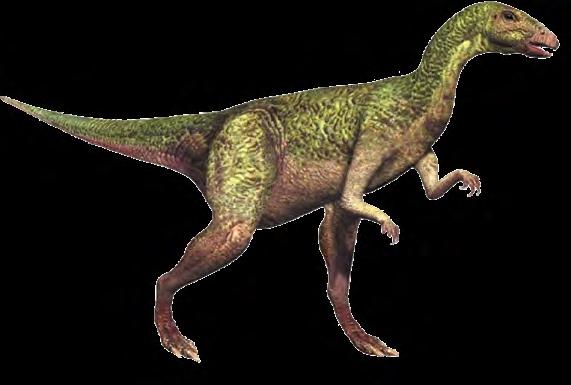

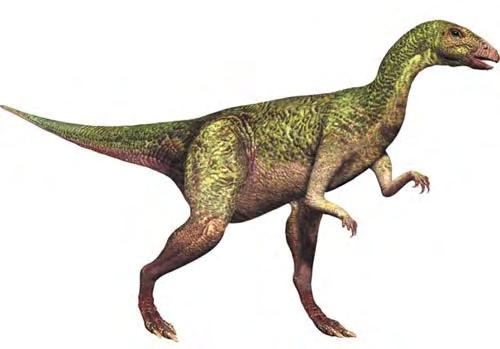

Herrerasaurus means

“Herrera’s Lizard.” It was small and quick. It had sharp teeth and claws; it was a carnivore and ate plant-eating dinosaurs.

145 to 66 Million Years Ago

The Triassic Period dates from 252 to 201 million years ago. Many dinosaurs in this period were small carnivores. They had hollow bones, walked on their hind legs and were quick. Herrerasaurus was a dangerous predator in the Triassic Period.

Paste years here

Paste years here

Paste dinosaur here Paste years here

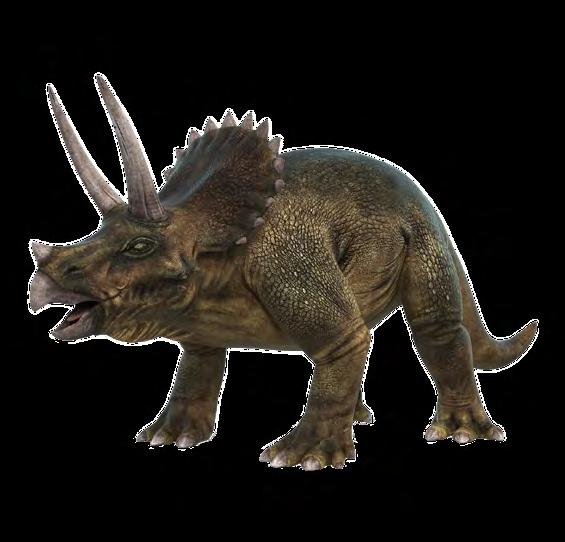

The Cretaceous Period dates from 145 to 66 million years ago. Herbivores, such as Triceratops and Ankylosaurus, lived in this period. They lived in herds to protect themselves from carnivores like Velociraptor. During the Cretaceous Period, dinosaurs became extinct.

Tyrannosaurus rex, a carnivore, was known to hunt herbivores like Triceratops.

201 to 145 Million Years Ago

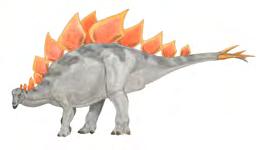

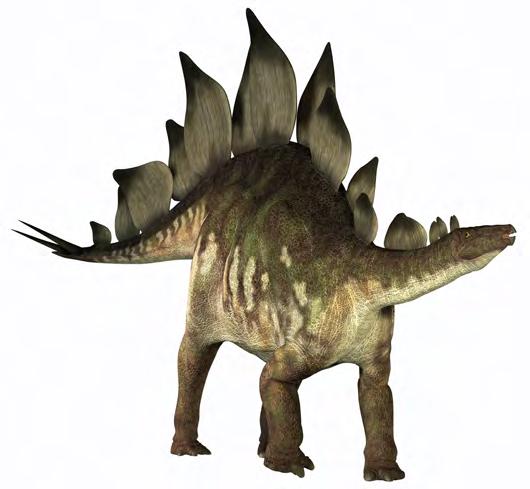

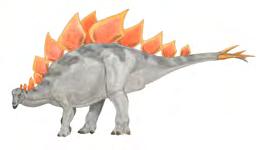

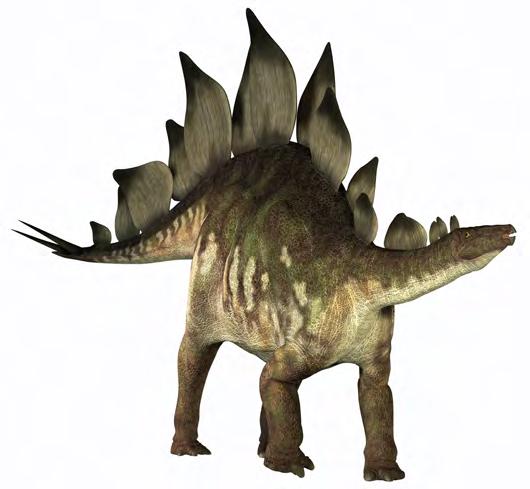

Stegosaurus was an herbivore that lived in the same time period as Brachiosaurus.

252 to 201 Million Years Ago

17

Pasted years visible here

Pasted years visible here

Pasted years visible here

Paste dinosaur here FOLD

Paste dinosaur here CUT CUT › ›

WHAT IS A DINOSAUR?

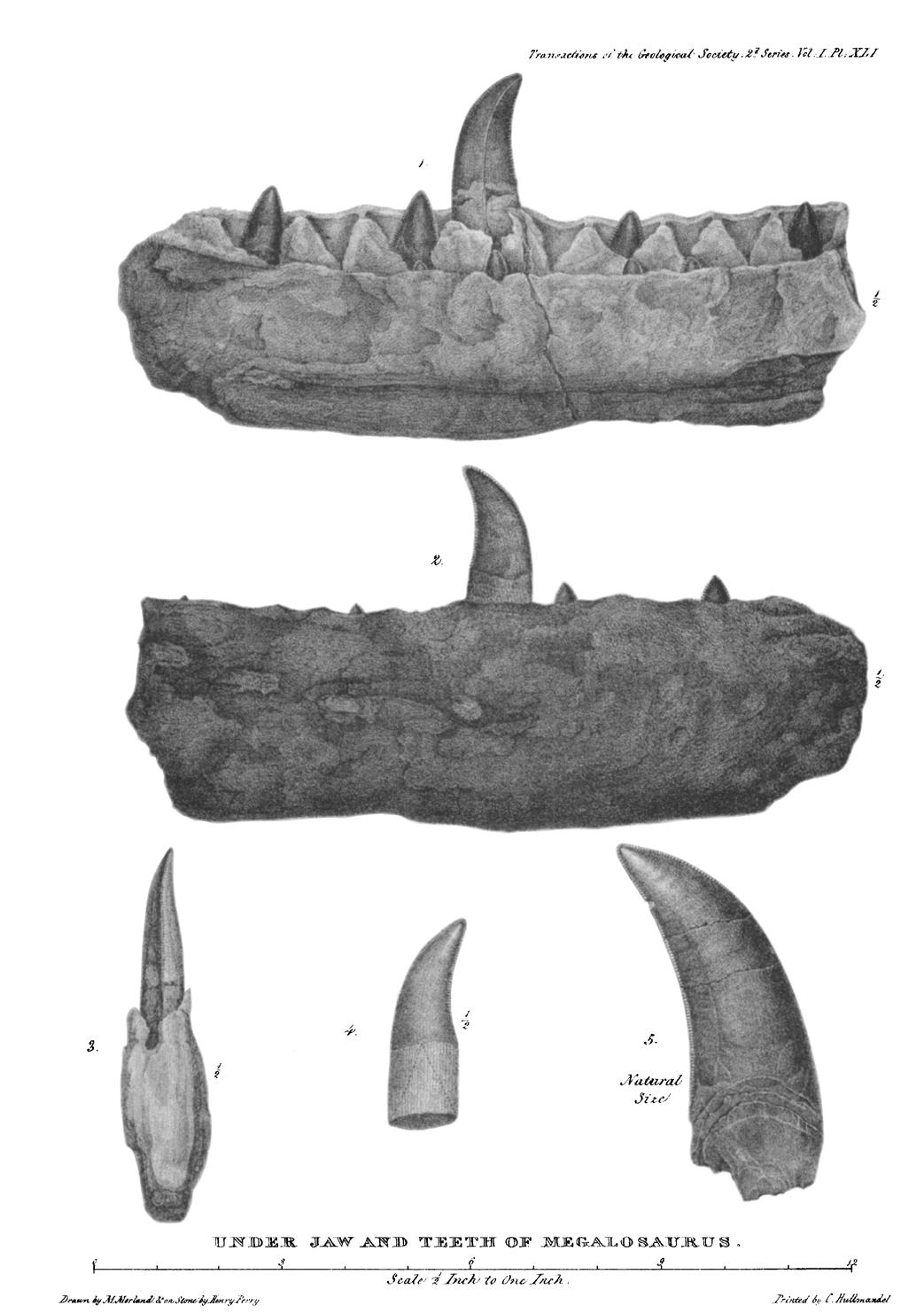

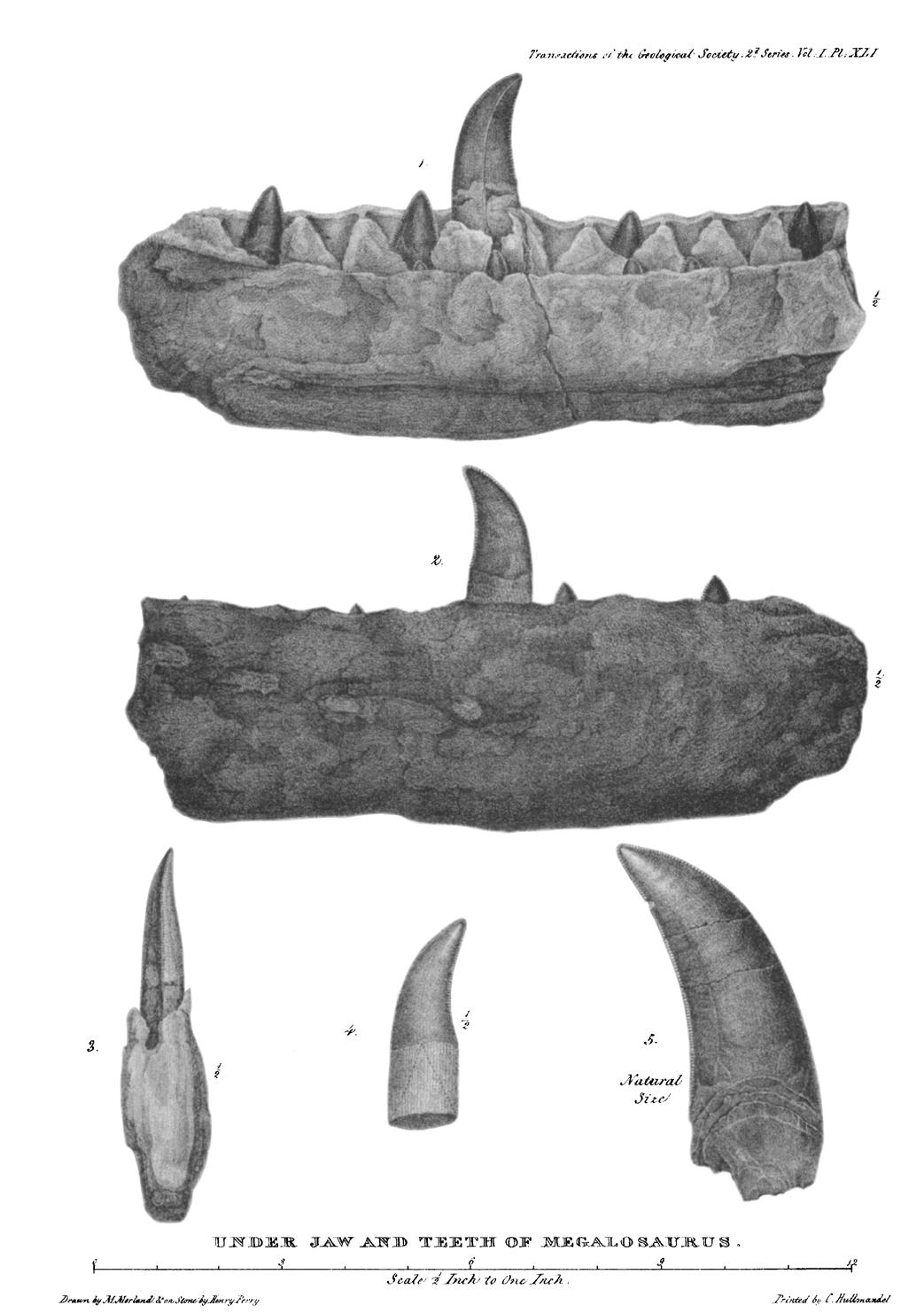

Dinosaur bones have existed for millennia, but it was not until 1842 that the term “dinosaur” was first coined. The first dinosaur to be described and named was presented as Megalosaurus (meaning “great lizard”). The bones and fossilized remains of this animal were found in the Oxfordshire village of Stonesfield in England.

learn more

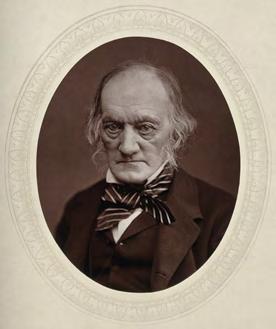

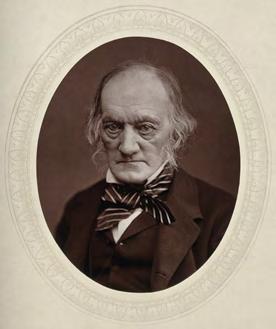

William Buckland, professor of geology at Oxford, presented descriptions of Megalosaurus’s discovery in a written paper, which was the first full account of a fossil dinosaur.

Click here to find out more about William Buckland.

Did you know?

Several of the first dinosaur discoveries were made in Oxfordshire.

Did you know?

The word “dinosaur” is a combination of two Greek words, “deinos” (terrible) and “sauros” (lizard).

The word “dinosaur” was invented by Richard Owen, following the discovery of several more creatures that shared common features with Megalosaurus. Owen was a distinguished professor of anatomy and he based this new “Dinosauria” grouping on the shared features of the recently discovered large terrestrial (living on land) reptiles Megalosaurus, Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus. He saw that these animals shared certain features (including hollow limb bones and five fused vertebrae where the spine fastens to the pelvis) and recognized that they were more than just the overgrown lizards that others had perceived them to be.

learn more

Click here to find out more about Richard Owen.

Prior to the 1800s, scientists struggled to interpret early findings of large bones that were occasionally dug from quarries. In 1677, before the discovery of dinosaurs, English naturalist and Oxford professor Robert Plot wondered if some of the large bones found could have been evidence of an elephant brought to Britain by the Romans. He finally concluded they were too large and so must be the remains of a giant!

Dinosaurs are a large, yet very specific group of creatures. The word “dinosaur” is often used incorrectly—many people lump together all ancient reptiles (including the flying reptiles and marine reptiles) and call them dinosaurs.

18

buckland

owen

19 at University of Southern California on April 9, 2014 http://trn.lyellcollection.org/ Downloaded from Drawings of Megalosaurus remains found in Oxfordshire

Richard Owen’s skill as an anatomist enabled him to begin creating a classification system for dinosaurs. He identified four key features and criteria which classed an animal as a dinosaur:

1. It must have lived during the Mesozoic Era.

2. It must be a reptile. (Although not all reptiles are dinosaurs. For example, lizards are reptiles, but they are not dinosaurs.)

3. Its legs must be located below its body, as opposed to sticking out from the sides like the legs of a crocodile.

4. It must have lived on land, not in the water like swimming reptiles, or in the air like the pterosaurs. (However, the fossil record indicates that birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic Period, and consequently birds are now considered a type of dinosaur in modern classification systems.)

Additionally, many dinosaurs share several other characteristics:

• A large hole in the bottom of their basin-shaped hip socket

• A secondary palate (uncharacteristic of reptiles) that permits eating and breathing at the same time

• A straight thigh bone with an inwardly turned head

• Two pairs of holes in the temporal region of the skull

• Backward-pointing knees (or elbows) of the front legs

• Forward-pointing knees of the rear legs (rather than pointing sideways in a lizard-like way)

• Front legs shorter and lighter than the rear legs (in almost every species)

• A special bone at the chin, capping the front of the bottom jaw (in some species)

20

Megalosaurus

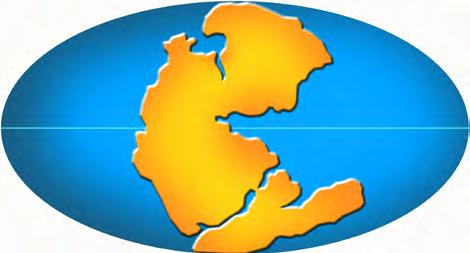

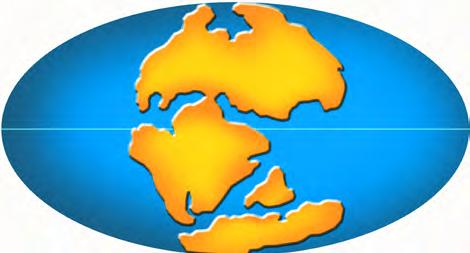

Dinosaurs evolved and adapted rapidly during their 165-million-year reign. Early in their evolutionary history, dinosaurs split into two major groups, defined by their different hip structures:

1. Saurischians (saw-RISS-kee-ins), meaning “lizardhipped” dinosaurs

2. Ornithischians (or-ne-THISS-kee-ins), meaning “bird-hipped” dinosaurs

If that’s not confusing enough, each group has several subgroups, too—and within each subgroup are several different species of dinosaur!

Have a look at the family tree below. It shows the two major groups with their subgroups, along with a small sample of each subgroup. It is impossible to say just yet exactly how many species of dinosaurs there are since the fossil remains of new species are still being discovered each year. Approximately 700 species have been named so far.

Even if all 700 named species are valid, that number is still less than one-tenth the number of currently known living bird species, less than one-fifth the

number of currently known mammal species, and less than one-third the number of currently known spider species—which shows potentially how many more types of dinosaurs there are still to discover.

It can take a long time for scientists and paleontologists to classify dinosaurs. Sometimes, a new dinosaur is discovered and named, only for paleontologists to realize later that it is actually a species already known to them!

paleontologist (n.) a person who studies the forms of life existing in prehistoric or geologic times through analyzing fossils of plants, animals and other organisms

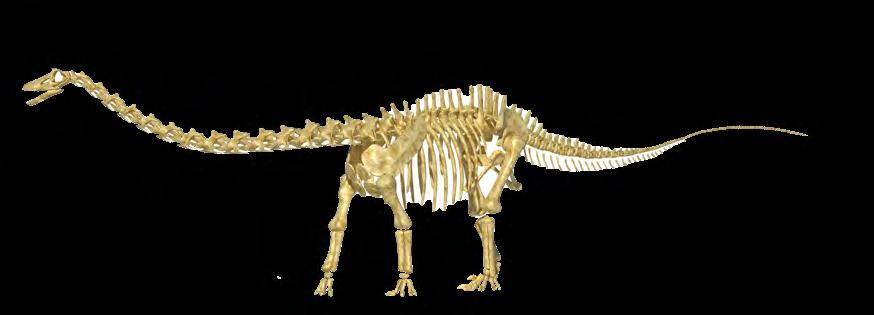

The most famous case of mistaken identity is possibly that of Brontosaurus. Brontosaurus used to be one of the most well-known dinosaurs until paleontologists realized that Brontosaurus was actually the same creature as Apatosaurus. Since Apatosaurus was discovered first, this is the name that has been used ever since, and the name Brontosaurus stopped being used.

pachycephalosaurs

ceratopsians

Saurischians

Saurischians included the biggest dinosaurs of all (the long-necked sauropods) and the fearsome, meat-eating theropods.

DINOSAURS

Ornithischians

Ornithischians included recordbreaking horned dinosarus, spiky stegosaurs and the armour-plated ankylosaurs.

21

sauropods theropods herrerasaurids stegosaurs ankylosaurs

ornithopods

WHAT IS A DINOSAUR?

Alabama Course of Study Standards

SC15.K.3 SC15.K.4 SC15.1.5 SC15.2.7 SC15.3.5 ELA21.K-4.R1 ELA21.1.17 ELA21.2.20 ELA21.2.22

ELA21.3.16 ELA21.3.18

National Standards

NS.K-4.3 NS.5-8.3 NS.5-8.4 NL-ENG.K-12.1 NL-ENG.K-12.4 NL-ENG.K-12.8

OBJECTIVE

By completing this activity, students will:

• Understand the difference between dinosaurs and other animals

MATERIALS

For this activity, you will need the following items:

• Pictures of dinosaurs

• Picture of lizard and bird

• “Dinosaur or Not?” handout on page 23

• Crayons

• Dinosaur books

• T. rex skeleton picture

PROCEDURE

To complete this activity, follow these steps:

1. Write “What Is a Dinosaur?” on the chalkboard. Tell students that today they will explore this question. Have students work in small groups. Distribute dinosaur books to each group. Give the groups 10 minutes to look through the books and find three interesting facts about dinosaurs. For younger students, pick one book and read it aloud in class.

2. Have groups report their facts to the rest of the class. Using the students’ responses, create a semantic map like the one shown.

3. Display the picture of the lizard and the picture of the dinosaur. Have students compare the stances and conclude that the lizard’s legs are sprawled out to the side, while the dinosaur’s legs are directly underneath its body. Tell students that all dinosaurs had a hole

in their hip socket that allowed them to stand this way. The hole in the hip socket distinguishes dinosaurs from other reptiles.

4. Call on volunteers to duplicate the lizard stance by assuming a crawling position and then moving their arms and legs out to the side: back feet should point forward, and hands should point slightly away from the body. Have volunteers walk forward as students observe. (They should shift their weight from side to side in a waddle, moving slowly and awkwardly.)

5. Call on volunteers to duplicate a quadrupedal dinosaur stance, with arms and legs positioned directly under their bodies. Have volunteers walk forward as students observe. (They should move more quickly, not as awkwardly.)

6. Distribute “Dinosaurs or Not?” to each student. Instruct students to look carefully at each animal and to color those that are dinosaurs. When students are done, review their answers with them. (The lion, woolly mammoth and alligator are not dinosaurs.)

7. Tell students that paleontologists at the American Museum of Natural History classify birds as dinosaurs. Tell students they will examine pictures of birds and a dinosaur to find similarities.

8. Have students work in groups. Distribute duplicates of the T. rex skeleton and pictures of birds. Have groups compare the two and note which features the two animals share. Give groups time to share their findings. (Some shared features are an S-shaped neck and three-toed foot.)

22

Dinosaur Hall of Fame

Well-Known Dinosaurs Throughout the World

There are so many dinosaurs that most of us are unfamiliar with the majority of them. Many interesting dinosaurs have not quite made it to the “Dinosaur Hall of Fame,” but perhaps in time, they will capture our imaginations the way T. rex and other popular dinosaurs have.

Have a look at our “Dinosaur Hall of Fame” on pages 25–35 to see a collection of the world’s best-known dinosaurs and learn more about them.

24

Dinosaur tracks in Comanche National Grassland, La Junta, Colorado

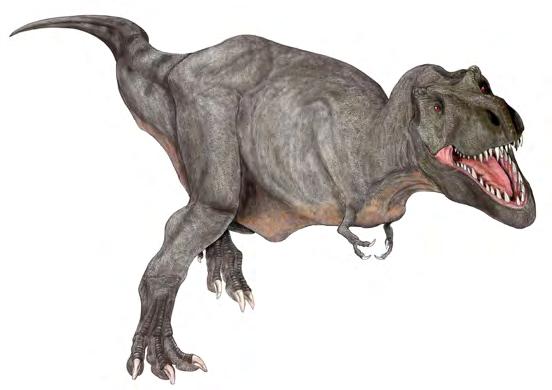

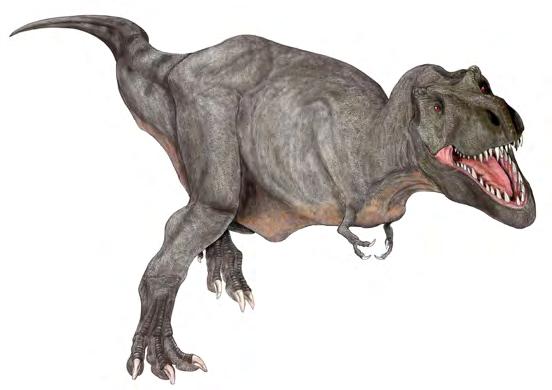

TYRANNOSAURUS REX

Tyrannosaurus rex is probably the most well-known dinosaur. It was first discovered by Barnum Brown in 1902 and soon captured the public imagination.

T. rex is a type of theropod dinosaur and was one of the first giant, meat-eating dinosaurs to be put on display in a museum. At the time, it was thought to be the largest, but since its discovery, even larger carnivorous dinosaurs have been discovered!

FACT FILE

How to say it: Ty-ran-o-SAWR-us-reks

Name means: “Tyrant lizard king”

Family group: Tyrannosauridae

Period: Late Cretaceous, 70–66 m.y.a.

Where found: North America

First discovered: 1902

Height: 13 feet

Length: 46 feet

Weight: 7.7 tons

Food:

Meat

Special features: Large, sharp teeth and powerful jaws

25

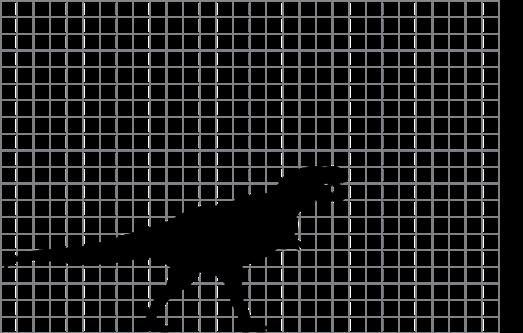

DINOSAUR-TO-HUMAN RATIO

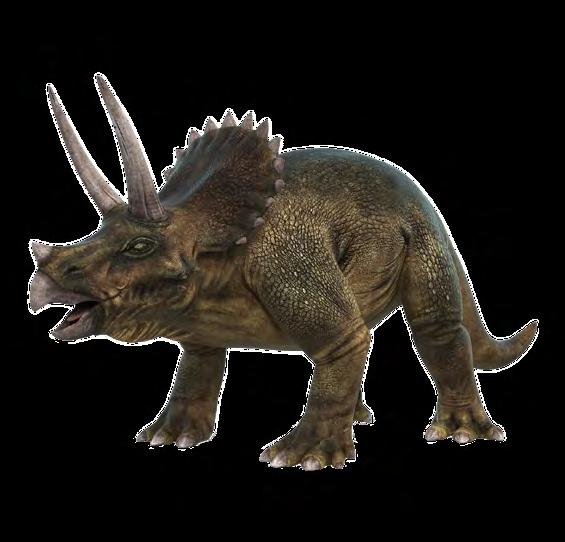

TRICERATOPS

Triceratops is a very large and distinctive dinosaur because of the three sharp horns on its head, which give it its name. Triceratops is classified as a cerapod and was one of the last dinosaurs to live on Earth.

FACT FILE

How to say it: Try-ser-RA-tops

Name means: “Three-horned face”

Family group: Ceratopidae

Period: Late Cretaceous, 70–66 m.y.a.

Where found: North America

First discovered: 1889

Height: 11 feet

Length: 29.5 feet

Weight: 6 tons

Food: Plants

Special features: Horns and frill

26

DINOSAUR-TO-HUMAN RATIO

STEGOSAURUS

Stegosaurus is the largest member of the Stegosauridae family but has one of the smallest brains, compared to its body size, of all known dinosaurs. The most impressive feature of Stegosaurus is the double row of large plates running along its back. Paleontologists once thought these were for defense, but current thinking is they were used to regulate temperature in some way.

FACT FILE

How to say it: Stay-guh-SAWR-us

Name means: “Roof lizard”

Family group: Stegosauridae

Period:

Late Jurassic, 154–146 m.y.a.

Where found: North America

First discovered: 1877

Height: 9 feet

Length: 29.5 feet

Weight: 3 tons

Food: Plants

Special features:

Double row of distinctive plates along its back

27

DINOSAUR-TO-HUMAN RATIO

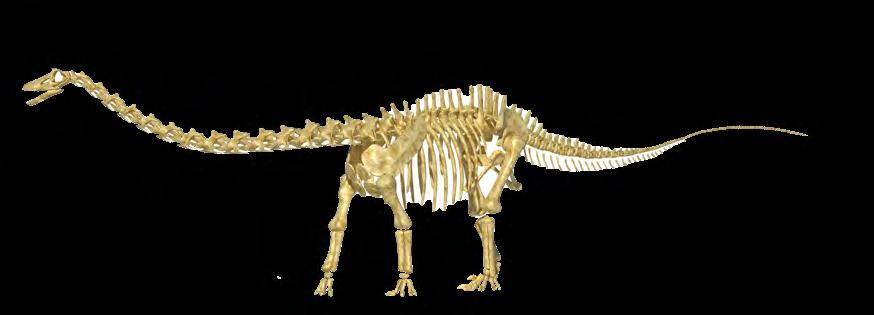

DIPLODOCUS

Diplodocus was one of the dominant plant-eating dinosaurs during the late Jurassic Period. Diplodocus belongs to the sauropod category of dinosaur.

FACT FILE

How to say it: Di-plo-DOH-kus

Name means: “Double-beam lizard”

Family group: Diplodocidae

Period: Late Jurassic, 161–145 m.y.a.

Where found: North America

First discovered: 1877

Height: 16 feet

Length: 88.5 feet

Weight: 12 tons

Food: Plants

Special features: Tall with a very long neck

28

DINOSAUR-TO-HUMAN RATIO

APATOSAURUS

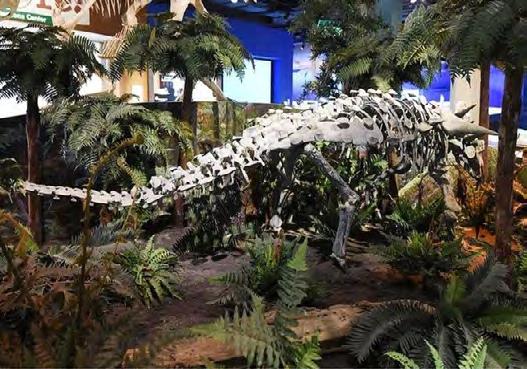

Apatosaurus is a large sauropod. For many years, the most complete skeleton of Apatosaurus was thought to be a different species and was named Brontosaurus. In the 1970s, it was finally proven that Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus were the same creature.

ApATOSAURUS

Apatosaurus is a large sauropod.

For many years, the most complete skeleton of an Apatosaurus was thought to be a different species and was named Brontosaurus. In the 1 970’s, it was finally proven that Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus were the same creature.

FACT FILE

How to say it: A-pat-oh-SAWR-us

Name means: “Deceptive lizard”

Family group: Diplodocidae

FACT FILE

Period:

Height: 13 feet

Length: 69 feet

Weight: 30 tons

Food: Plants

How to say it: A-pat-oh-sore-rus

Late Jurassic, 161–145 m.y.a.

Name Means:

Where found:

Deceptive Lizard

North America

Family Group: Diplodocidae

Period:

First discovered: 1877

Late Jurassic 145 – 161 MYA

Where found: North America

Special features: Enormous size and weight

DINOSAUR-TO-HUMAN RATIO

1st Discovered:

29

16

Enormous size and weight

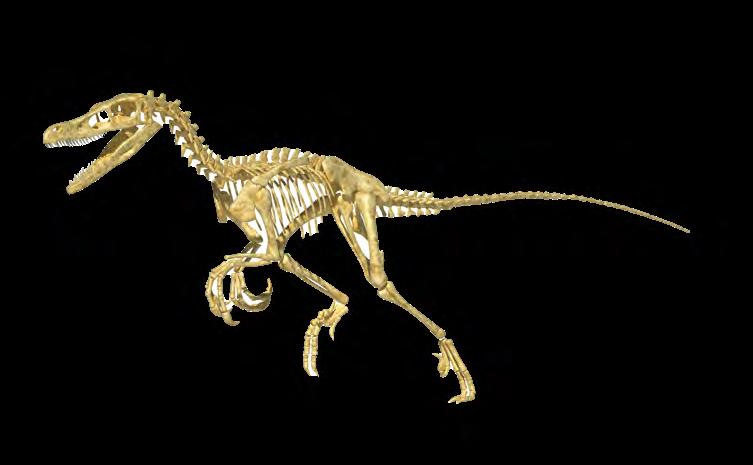

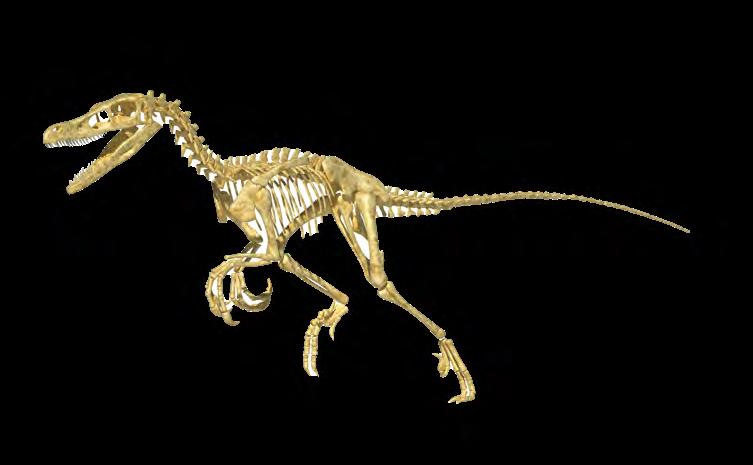

VELOCIRAPTOR

Velociraptor was an agile, fast-running hunter. It was not the largest of predators, but its keen intelligence and teamwork made it a very successful killer.

How to say it: Vel-OSS-ah-rap-tor

Name means: “Fast robber”

Family group: Dromaesauridae

Period: Late Cretaceous, 70–65 m.y.a.

Where found: Mongolia

First discovered: 1924

Height: 3 feet, 3 inches

Length: 6.5 feet

Weight: 33 lbs.

Food:

Meat

Special features: Intelligence and deadly claws

30

FACT FILE

DINOSAUR-TO-HUMAN RATIO

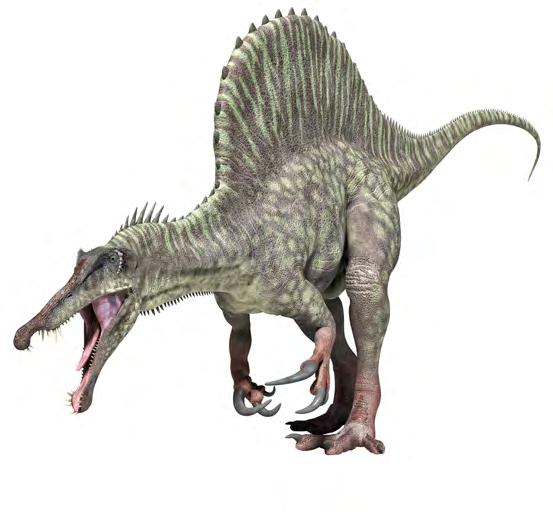

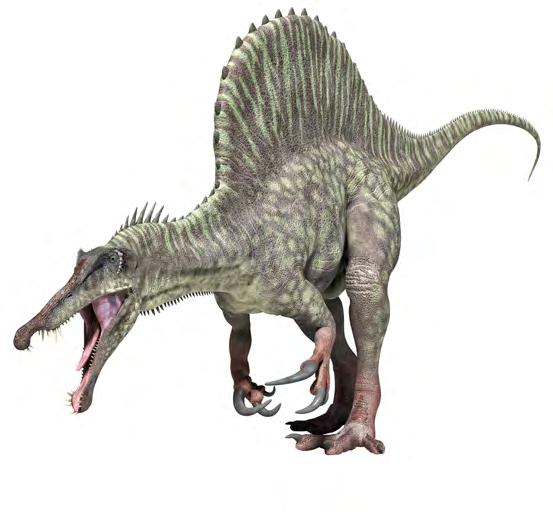

SPINOSAURUS

Spinosaurus is a very large carnivore, significantly larger than T. rex and with a skull about three feet longer than most T. rex skulls.

How to say it: Spine-oh-SAWR-us

Name means: “Thorn lizard”

Family group: Spinosauridae

Period: Late Cretaceous, 135–90 m.y.a.

Where found: North Africa

First discovered: 1915

Height: 16 feet, 5 inches

Length: 52 feet

Weight: 4 tons

Food:

Meat

Special features: Large, sail-like crest along its back

31

FACT FILE

DINOSAUR-TO-HUMAN RATIO

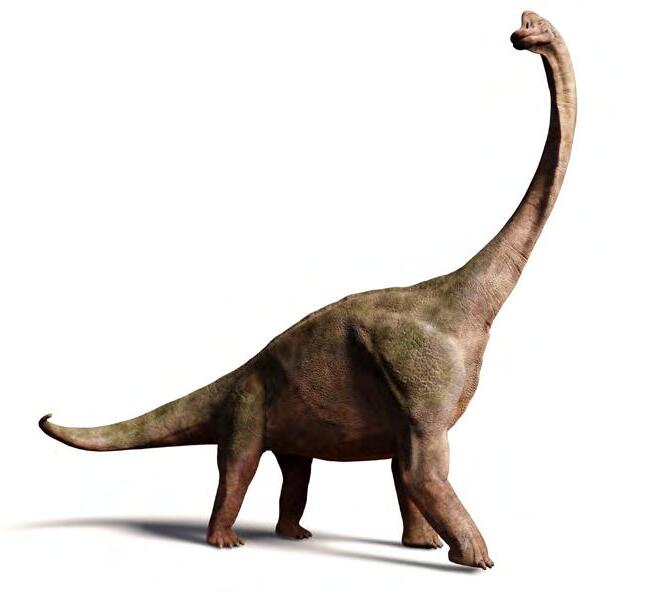

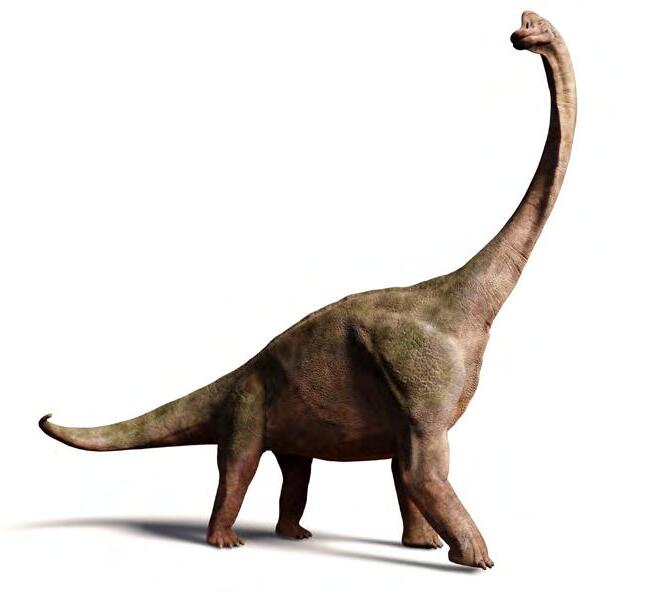

BRACHIOSAURUS

Brachiosaurus is one of the largest known land animals. Its large nostrils were located on top of its head, which caused speculation that Brachiosaurus might have spent time submerged in water. However, recent studies have shown that a creature as large as Brachiosaurus could not have inhaled and inflated its lungs against the water pressure at depths of total submergence.

FACT FILE

How to say it: Brak-ee-oh-SAWR-us

Name means: “Arm lizard”

Family group: Brachiosauridae

Period:

Late Jurassic, 161–145 m.y.a.

Where found: North Africa and North America

First discovered: 1900

Height: 52 feet, 6 inches

Length: 98 feet, 5 inches

Weight:

50 tons

Food: Plants

Special features:

Extreme height and weight

32

DINOSAUR-TO-HUMAN RATIO

DRYOSAURUS

bipedal and had powerful back they were fast runners. Their the body while standing or herbivores, using their hard and plants, and their oak at the back of their mouth Dryosaur fossils have been Western United States, Tanzania Zealand.

FACT FILE

Dryosaurus was bipedal and had powerful back legs, so it is likely it was a fast runner. Its stiff tail balanced its body while standing or moving. Dryosaurus was an herbivore, using its hard beak to cut leaves and plants, and its oak leaf-shaped teeth at the back of its mouth to grind them up. Dryosaurus fossils have been found in the western United States, Tanzania

FACT FILE

How to Say it: Dry-O-sore

How to say it: Dry-OH-sawr-us

Name Means: Oak Reptile or Tree Lizard

Name means: “Oak reptile” or “tree lizard”

Family Group: Dryosauridae

Family group: Dryosauridae

Period: Late Jurassic 145 - 161 MYA

Where Found:

Period: Late Jurassic, 161–145 m.y.a.

North America and Southern Hemisphere

Where found:

1st Discovered: North America, 1880’s

North America and Southern Hemisphere

Height: 5 feet

Length: 12 feet

Weight: One ton

Food: Plants

Special Features: Beak. Five finger gripping food

First discovered: 1880s

Height:

5 feet

Length:

12 feet

Weight: 1 ton

Food: Plants

Special features: Beak, five fingers for gripping food

33

puppet Zoo Live

Baby Dryosaurus puppetinErth’sDinosaur Zoo Liv e

DINOSAUR-TO-HUMAN RATIO

many dinosaurs been dug (and at Dinosaur Cove Leaellynasaura is discovery and is specimens including two and two fragmentary turkey-sized (with a long herbivorous ornithopod. In areas of current Antarctic Circle extreme, with limited Its skull has which suggests to the long winter could withstand temperatures.

LEAELLYNASAURA

Leaellynasaura is one of many dinosaurs whose partial remains have been dug (and blasted) out of the solid rocks at Dinosaur Cove in Southeastern Australia. Leaellynasaura is a relatively recent dinosaur discovery and is known from several specimens including two nearly complete skeletons and two fragmentary skulls.

FACT FILE

How to Say it : Lee-el-in-a-sore-rah

FACT FILE

FACT FILE

How to Say it : Lee-el-in-a-sore-rah

Name Means: Leaellyn’s Lizard

Leaellynasaura is one of many dinosaurs whose remains have been excavated from the solid rocks at Dinosaur Cove in southeastern Australia. Leaellynasaura is a relatively recent discovery. Its body is approximately the size of a turkey, with a long tail, and it is an herbivorous ornithopod. In the early Cretaceous Period, areas of currentday Australia were within the Antarctic Circle. Leaellynasaura has unusually large eye sockets, which suggests that it adapted to the long winter darkness of the Antarctic and could withstand low, possibly subzero, temperatures. To do this, it would have needed a method of generating body heat, which some have taken as evidence that dinosaurs were in fact warm-blooded.

Name Means: Leaellyn’s Lizard

Family Group: Undecided!

Period:

Its body was roughly turkey-sized (with a long tail) and it was an herbivorous ornithopod. In the early Cretaceous period, areas of current day Australia were within the Antarctic Circle where the climate was extreme, with limited sun visible much of the year. Its skull has unusually large eye sockets, which suggests that Leaellynasaura adapted to the long winter darkness of the Antarctic and could withstand low, perhaps even subzero, temperatures. To do this, it would have needed a way of generating body heat, which some people have taken as evidence that dinosaurs were in fact warm-blooded.

needed a way of some people have dinosaurs were in fact

Family Group: Undecided!

How to say it: Lee-el-in-a-SAWR-ah

Period:

Height: Unknown

Early Cretaceous 104 - 112 MYA

Name means: “Leaellyn’s lizard”

Where Found: Australia

Length: 6 feet, 6 inches

Family group: Undecided

Early Cretaceous 104 - 112 MYA

Where Found: Australia

1st Discovered: Australia, 1989

Height: Unknown

Length: 6-1/2 feet

Weight: Unknown

Food: Plants

Weight: Unknown

1st Discovered: Australia, 1989

Period:

Early Cretaceous, 112–104 m.y.a.

Where found: Australia

Height: Unknown

Length: 6-1/2 feet

Weight: Unknown

First discovered: 1989

Food: Plants

Food: Plants

Special features:

Long tail compared to body size

DINOSAUR-TO-HUMAN RATIO

Special Features: Long tail compared to body size

Special Features: Long tail compared to body size

34

Both images are Leaellynasaura puppets in Dinosaur Zoo Live

Leaellynasaura

i v e

Leaellynasaura puppetinErth’sDinosaur Zoo L

TITANOSAURUS

Titanosaurus was the largest animal ever to live on land; it was a sauropod dinosaur that survived to the end of the Cretaceous Period (most sauropods went extinct at the end of the Jurassic). Titanosaurus grew to sizes far in excess of its earlier relatives; hence it is named after the Titans, who were gods in Greek mythology. The largest Titanosaurus that can be factually estimated is Argentinosaurus, which grew up to 114 feet and 9 inches in length! Titanosaursus discovered in Australia include Wintonotitan Wattsi and Diamantinasaurus Matildae.

were the largest animals roam on land; they were sauropod that survived to the end of the period (most sauropods went the end of the Jurassic period). grew to sizes far in excess earlier relatives; hence they are after the mythological Titans, who of ancient Greece.

Titanosaur that we factually estimate the size is Argentinosaurus, it grew up to 114 fett 9 length! Titanosaurs discovered include Wintonotitan Wattsi

FACT FILE

How to Say it: Tie-tan-O-sore

Name Means: Titanic Lizard

Family Group: Titanosauridae

FACT FILE

How to say it: Ty-tan-OH-sawr-us

Name means: “Titanic lizard”

Family group: Titanosauridae

Period:

Height: Up to 60 feet

Length: Up to 115 feet

Weight: Up to 100 tons

Food:

Diamantinasaurus Matildae.

Period: Cretaceous 65 - 96 MYA

Where Found: All continents

1st Discovered: South America and India in 1877

Height: Up to 60 feet

Length: Up to 115 feet

Weight: Up to 100 tons

Food: Plants

Special Features: Very Large!

Cretaceous, 96–65 m.y.a.

Where found: All continents

First discovered: 1877

Plants

Special features: Extreme size, last surviving sauropod

Last surviving sauropod

DINOSAUR-TO-HUMAN RATIO

35

ITANOSAUR

puppet in Dinosaur Zoo

L i v e

Live Titanosaurus puppetin

Erth’sDinosaur Zoo

SCALES, SPIKES, FEATHERS OR FUR?

No one knows exactly what colors or patterns most dinosaurs exhibited. Coloring and pattern are suited to the functions that an organism needs to survive. Some dinosaurs were likely camouflaged in order to hide from predators or to sneak up on prey. Some may have been colored in a particular way to attract mates, and some may even have been brightly colored to ward off predators. Colors are also important for temperature regulation because different colors absorb or reflect sunlight. Fossilized skin impressions have only been found for a small fraction of known dinosaurs. Not much is known about dinosaur skin, and there is some debate among paleontologists on this topic.

Most skin fossils show bumpy skin; only the huge plant-eaters appear to have had scaly skin. Some of the bird-like dinosaurs even had feathers.

Did you know there are dinosaurs flying in our skies today?

Despite almost one hundred years of disagreements, most scientists now acknowledge that today’s birds are the ancestors of small meateating dinosaurs. The development of feathers turned dinosaurs that could run or climb into birds that could fly.

The earliest true bird is Archeopteryx, which lived during the late Jurassic Period. When Archaeopteryx remains were first unearthed, paleontologists quickly realized this was one of the most important dinosaur discoveries ever made because Archaeopteryx was the first feathered dinosaur ever found.

Other dinosaurs developed feathers but remained flightless, just like several types of current birds, such as ostriches, emus and kiwi, to name just a few.

ARCHAEOPTERYX

FACT FILE

How to say it: Ar-kee-OP-ter-iks

Name means:

“Ancient wing”

Family group: Coeluridea

Period: Late Jurassic 150–125 m.y.a.

Where found: Germany

First discovered: 1861 (but not classified as a dinosaur)

Height: Approximately 1 foot

Length: 1 foot, 8 inches

Weight: 1 lb., 1.67 oz.

Food: Meat

Special features: Feathers

learn more Click here to find out more about the feathered dinosaurs.

36

IN THE AIR

At the time of the dinosaurs, there were a group of winged reptiles known as pterosaurs.

Pterosaurs were related to dinosaurs but are not classified as dinosaurs themselves. They had wings made of skin that stretched between long finger bones and legs. They did not evolve feathers.

IN THE AIR

At the time of the dinosaurs, there were a group of winged Pterosaurs are related to dinosaurs but are not classified had wings made of skin that stretched between long finger not evolve to have feathers. Pterosaurs died out at the end the same time as the dinosaurs and did not evolve into

Pterosaurs died out at the end of the Cretaceous Period, at the same time as the dinosaurs, and do not share an evolutionary line with modern-day birds.

learn more

Click here to find out more about pterosaurs.

Click HERE to find out more about Pterosaurs

BELOW THE WAVES

While dinosaurs ruled the land and pterosaurs (and eventually Archeopteryx) ruled the air, the ocean was home to many such as Nothosaurs, Ichthyosaurs, Pliosaurs, Plesiosaurs, Most were fierce carnivores survived preying on other sea other. Although they lived in the sea, many of these prehistoric (like whales do).

Click HERE to find out more about prehistoric sea life.

BELOW THE WAVES

While dinosaurs ruled the land and pterosaurs (and eventually flying dinosaurs like Archeopteryx) ruled the air, the ocean was home to many species of marine reptiles such as Nothosaurus, Ichthyosaurus, Pliosaurus, Plesiosaurus, Mosasaurus and Elasmosaurus. Most were fierce carnivores who survived by preying on other sea creatures, and on each other. Although they lived in the sea, many of these prehistoric creatures breathed air (like whales do).

learn more

Click here to find out more about prehistoric sea life.

37

Plesiosaurus puppe

26

Plesiosaurs from Dinosaur Zoo Live

38

Dinosaur fossils at the Natural History Museum of London, United Kingdom

FOSSILS

Dinosaurs are a great part of our world’s natural history. We know that dinosaurs and other extinct animals and plants existed because of the fossils

Did you know?

Fossils are the preserved remains or traces of animals, plants and other organisms from the remote past.

Fossils offer physical evidence of life prior to human history. This prehistoric evidence includes the remains of living organisms, prints and molds of their

physical form, and marks and traces created in the sediment by their activities. Dinosaur fossils come in many types, from preserved bones, to tracks and more. Some fossils are better preserved than others and show impressions of skin and other soft tissues. Fossil remains left by dinosaurs prove that they existed, and we are able to use the fossil evidence to recreate their skeletons and then start to create pictures of what they might have looked like.

There is still so much to learn about dinosaurs, and new fossil discoveries are being made all the time!

take a look

Click here to watch a video about how fossils are formed.

39

EXPLORING FOSSILS

Alabama Course of Study Standards

SC15.3.9 SC15.4.12 SC15.6.6 SS10.3.13.1

National Standards

NS.K-4.1 NS.K-4.3 NS.5-8. NS.5-8.3 NS.5-8.4

OBJECTIVE

By completing this activity, students will:

• Compare and explain some processes of fossilization

• Construct a model of an excavation site

• Model the thinking skills and actions of a paleontologist

Overview: This lesson plan consists of two parts. In Part I, students examine the process of fossilization. In Part II, students act as paleontologists and go on a fossil hunt. After students have successfully completed their cleaning and identification, a “museum” could be set up to show off their work. Collecting boxes are easy to come by and not expensive. Student labels can be fixed to the box and the fossil cradled on felt or cotton batting for protection from sliding or bumping on the sides of the box. It is recommended that as little is said as possible by the teacher, offering students the opportunity to express their own ideas.

Note to teachers: The excavation process (Part II) can happen an hour after the plaster has set but might work best (i.e., make the fossil hunt seem more realistic) if it is done several days after Part I has been completed. Another option is to pre-make an excavation site so one is ready to go whenever your group is ready for Part II.

Safety: Plaster of Paris can pose an inhalation hazard and excavation tools could cause bodily harm if used inappropriately. Review safety tips with your class before each part of this lesson.

Sources and resources:

X Fossils Facts and Finds Lesson Plan

X “I Am a Paleontologist” (They Might Be Giants)

X Environmental Science Institute – Laura Sanders

MATERIALS

For this activity, you will need the following items: part i

• Inexpensive fossils as an engagement example (if possible)

• Shrimp shell (a workable fossil substitute)

• Escargot shell (a workable fossil substitute)

• Plaster of Paris

• Pitcher of water

• Sifter

• Fine sand, fine enough to go through sifter

• Small disposable aluminum baking pans or other waterproof container

• Small plastic or rubber dinosaur

part ii

• Prepared plaster of Paris “rock” containing fossil specimens

• “Chisels” (i.e., a metal butter knife or small screwdriver set, ranging in size from a tiny eyeglasses screwdriver to about an eighth of an inch)

• Magnifiers of various types, best if they are mountable to allow for hands-free work while observing fossils through the magnifiers

• Small bottle of vinegar with an eyedropper

• Clear nail polish

PROCEDURE

To complete this activity, follow these steps:

1. Teacher Preparation:

For Part I, mix a small amount of fine sand with the plaster of Paris. DO NOT ADD WATER. Put about a third of the dry mixture in a waterproof container. Separate the remaining mixture into two containers. Mix a small amount of dry tempera paint to create different shades of brown. Mix the colors into the containers to make two distinct colors of powdery sand so the layers will show as different “soil” as it is added.

For Part II, before the lesson, remove the solid plaster of Paris from the aluminum tray. Have enough tools set up so a group of four students can share a complete set.

2. Activity: part i: fossilization

Pass around sample fossils. If possible, have examples of both cast and mold varieties. For an even better impression, try to have a sample that is the positive/negative impression of both cast and mold of the same fossil.

ask sudents: What is this? What do you notice about these fossils? What seems the same? What seems different? How do you think these differences happened? How are fossils formed? What can fossils tell us?

40

Your discussion could include experiences they might have had making clay or dough molds, baking a Bundt cake, making molded candies or a Jell-O mold, etc. Have the class come up with a definition of a fossil and write it on the board.

Exploration and Explanation: Scientists think that life in the ancient seas might have been similar to modern sea life in many ways, such as salty water, sea plants and invertebrates (animals with no backbone) such as sea snails who have an exoskeleton on the outside of their bodies. We know about these ancient animals because they leave fossils.

ask students: How do you think these fossils of sea invertebrates would have been formed?

Discussion could include the shells falling to the sea floor, becoming buried in the sediment and filling with the soft sand of the ocean bottoms.

Bring out the prepared container of plaster of Paris and explain that this is a model of the ancient sea floor.

ask students: What is a model? How is this model of the ancient sea floor the same or different from the actual thing? How can models help us explore ideas? What could we do to make this model a better learning tool for us?

Discussion could include the fact that the model is soft, sandy and powdery; however, it is not wet as it would be at the bottom of the sea. It is not as large as the sea floor, which is good for students because it fits in the classroom but is significantly smaller and doesn’t show other life or things that might exist there.

a. Place the shells in the dry plaster of Paris.

b. Pour a small amount of water onto the layer of plaster of Paris and shells.

ask students: Adding water reminds us that this is a model of the ancient ocean. What else would the animals’ bodies be exposed to?

Discussion could include the animals’ bodies being exposed to currents, waves, turbulence, predators or scavengers eating the soft fleshy parts of their bodies and leaving behind the hard shells. The soft bodies decomposed or disappeared, and then the hard shells would fill up with sediments and mineral-laden water.

Using the sifter, sift a small amount of the remaining plaster and sand evenly over the water, allowing it to sink in and cover the shells. This activity shows that sand and other sediments would eventually cover the ancient animals’ bodies.

d. Continue to sift the plaster until a soft mud is formed. (Keep adding the plaster until all the water is absorbed. The plaster will now dry rather quickly. Plaster of Paris sets in about 30 minutes.)

ask students: How long would the process of fossilization take place?

Discussion could include possible answers of days, weeks, thousands or millions of years. Over time, the ancient sea might begin to dry up.

ask students: Why would this have happened? How would this change the seabed? What would happen to the shells?

Discussion could include that there are many possible causes, such as movements of Earth’s crust, changes in temperature, or volcanic actions. As the water level got lower, muddy swamps and thick vegetation that grew there made good homes for species that could breathe the air. As they walked through the swamps, their heavy bodies left tracks in the soft mud.

e. Take a plastic or rubber dinosaur and make an imprint of their footprints.

ask students: What do you think will happen to these tracks? These footprints? What could we learn from these types of fossils?

Discussion could include the difference between fossils that are imprints and the fossil relics that will be left by the shells.

Allow the plaster to dry. Fossilization is a long, slow process. It takes many thousands or millions of years for a fossil to form. Minerals in the water and sediment are left in tiny holes or pores in the shell or bone. Eventually, one molecule at a time, the minerals replace the original structures. What is left is a stone that looks exactly like the shell or bone that once existed.

41

42

part ii: paleontology

As students arrive, the song “I Am a Paleontologist” by They Might Be Giants could be playing in the background. This song can be found on CD, or through the video where the matching of dinosaur bones can be viewed along with the song HERE. Part of the video shows children paleontologists guessing which dinosaur skeleton a particular bone belongs to.

Exploration and Explanation:

Note that all script to be read aloud to students is bold and italicized.

a. The rock in front of you is ready for the painstaking process of removing fossils from it. The paleontologist who sent these to us needs your help to carefully expose or remove the fossil. Since the fossil could be fragile and easily damaged, we need to do this with a great deal of care. The slightest chip in the workplace could ruin the fossil we are trying to expose.

b. When paleontologists are working at a dig site, they might see just a small part of a fossil sticking out of the rock formation or even just an impression above the ground that would lead them to suspect a fossil was contained in the rock at that location.

The first step of the fossil hunt is to decide where the fossil might be hiding. Look at your rock to see if there are any bumps or ridges that might indicate a fossil burial.

Allow students time to decide where the fossil could be hidden beneath the surface. Help them to use a pencil to outline the area. Bumps or other irregularities in the surface are typical clues.

c. Once you decide where you want to start your dig and have marked it with a pencil, use a metal butter knife or scraper to gently scrape off the top layer of rock just outside the pencil lines.

As you work, you may begin to see the edges of the fossil. Carefully scrape around the edges until you think you have a good outline of the fossil.

It will take some time for the fossil to reveal itself. It is important for students to remove the matrix a little at a time using a scraping technique. In this exercise, you won’t need to do any chipping with hammers.

The fossil might stay embedded in the rock matrix, using the matrix as a sort of ready-made stand. In this case, students would clean a neat “trough” around the

edges of the fossil and then clean the surface of the fossil. Alternatively , students can work on removing the fossil entirely. This may take a bit longer, but it will also allow the opportunity to try some additional techniques for removal. (See step “e” below.)

d. Next use a brush to gently remove the “rock” that is covering the fossil. If some of the rock is thick, you can carefully scrape at it with a chisel. Be extra careful, though, because you could chisel off a part of the fossil.

Students will continue working to remove the rock around the fossil. The following are some suggestions that imitate the work of a paleontologist in the lab.

e. If the fossil is tightly embedded and scraping away the matrix seems too great a challenge, you can use a mild acid solution to help dissolve the matrix away. In the lab, paleontologists protect the exposed parts of the fossil from the acid by painting it with a special glue.

Students can imitate this process using vinegar drops on the matrix around the fossil. Since vinegar is so mild, they can use it directly on the fossil to remove excess matrix. Once most of the fossil is cleaned, ask students to coat the fossil with clear nail polish to imitate the protective glue coating.

f. The last step to completing your fossil hunt is to note the type of fossil, date of acquisition or discovery, and the location. Once your fossil is cleaned and ready for display, make a small information card that shares the name of the fossil, the geologic time period and the location where it was found.

43

IMPORTANT NAMES IN PALEONTOLOGY

The following people played a key role in early dinosaur paleontology:

Gideon Mantell (1790–1852) was an English doctor from Sussex. Mantell was a paleontologist throughout his life and contributed greatly to the field through his discovery and analysis of many fossilized remains. One of the stories told about Mantell is that his wife found a tooth that looked like it belonged to a very large iguana, and it was many years before Mantell managed to complete the skeleton which turned out to be Iguanodon.

Mary Anning (1799–1847) was a fossil collector who gained a reputation as a paleontologist. She lived in Lyme Regis and made many important prehistoric discoveries. She started fossil collecting to earn money and although women and the lower classes were not usually respected in scientific circles, Anning managed to make an impact.

Sir Richard Owen (1809–1892) was an English anatomy professor and paleontologist. He’s best known for inventing the term “dinosaur” (meaning “terrible lizard”). Owen was a central character during the early days of dinosaur discovery.

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807–1894) was an English sculptor and artist with an interest in natural history. He built the life-size Crystal Palace dinosaurs under the scientific direction of Richard Owen. Unfortunately, later discoveries revealed that many of the assumed body positions of the dinosaurs were incorrect. For example, we now know Megalosaurus was bipedal, though it was originally depicted on all fours. (Bipedal describes any creature that walks on its two back limbs.)

Can you imagine how difficult it is for paleontologists to reconstruct a dinosaur from fossils and bones and then trying to imagine what it looked like using only this small and incomplete amount of evidence?

Paleontologists need to be able to identify which bones belong to which type of creature, and they need to separate all the bones they discover into the different species of dinosaur. They also must identify which part of the body each bone belongs to. It must be very difficult, and so it is understandable that sometimes mistakes are made when identifying and classifying dinosaurs.

learn more

Click here to dig for fossils.

learn more

Click here to explore fossils.

learn more

Click here to dig for fossils and assemble the dinosaurs.

44

45

“I AM A PALEONTOLOGIST”

Alabama Course of Study Standards

SC15.3.9 SC15.4.12 ELA21.K-4.R1 ELA21.2.35 SS10.3.13.1

National Standards

NS.K-4.3 NS.5-8.3 NS.5-8.4 NL-ENG.K-12.3 NSS-USH.K-4.4

OBJECTIVE

By completing this activity, students will:

• Know how a paleontologist looks for and uncovers fossils

• Practice listening skills

MATERIALS

For this activity, you will need the following items:

• Technology for playing the video

• “I Am a Paleontologist” worksheet on page 47

PROCEDURE

To complete this activity, follow these steps:

1. Watch this video of “I Am a Paleontologist” by They Might Be Giants. The lyrics are included below.

I love diggin’ in the dirt

With just a pick and brush

Finding fossils is my aim

So I’m never in a rush

‘Cause the treasures that I seek

Are rare and ancient things

Like Velociraptor’s jaw

Or Archaeopteryx’s wings

Now all the kids

Who wanna see ‘em

Are lining up

At our museum

I am a paleontologist

That’s who I am, that’s who I am, that’s who I am

I am a paleontologist

That’s who I am, that’s who I am, that’s who I am

Could it be an herbivore

Crushing plants with rounded teeth

Or ferocious carnivore

Who moves so quickly on its feet

It’s like pieces of a puzzle

That I love to try and solve

It’s so fun to think about

How a species has evolved

Is it a T-rex? (I keep digging, digging, digging, digging)

(Digging, digging, digging, digging)

Maybe a Triceratops? (Digging, digging, digging, digging)

(Digging, digging, digging, digging)

Or a Carnotaur? (Digging, digging, digging, digging)

(Digging, digging, digging, digging)

(Digging, digging, digging, digging, diggin’)

Pachycephalosaurus?

2. After watching the video, talk to students about fossils and paleontology. Discuss how paleontologists search for and unearth fossils and how their work has contributed to our knowledge of dinosaurs. Discuss some of the important names in paleontology.

3. Watch the video again and tell students to pay close attention to the information in the song.

4. Pass out the worksheet and allow students the opportunity to complete as many questions as they can from what they heard in the song.

5. Watch the video one more time and allow students to check their answers.

6. For younger students, the worksheet could be completed together as a class.

46

An herbivore crushesplantswithits teeth.

The Jay and Susie Gogue Performing Arts Center at Auburn University

The Jay and Susie Gogue Performing Arts Center at Auburn University

Walter Stanley and Virginia Katharyne Evans

Woltosz Theatre

Walter Stanley and Virginia Katharyne Evans

Woltosz Theatre

Erth’s Dinosaur Zoo Live

photo: David Rugeles

Erth’s Dinosaur Zoo Live

photo: David Rugeles