7 minute read

Australia’s Ageing Aquatic Facilities

The $80 million redevelopment of the Adelaide Aquatic Centre was a signifi cant issue during this year’s South Australian election.

The Timebomb under Australia’s ageing aquatic facilities

Advertisement

A new Royal Life Saving report has found that in the next 10 years, up to 40% of public aquatic facilities that local governments own will need serious refurbishment or outright replacement at a cost of over $8 billion. RJ Houston reports

The significant contribution that aquatic facilities deliver is now indisputable through quantifiable data, and we are also more informed about the number and the profiles of aquatic facilities across the country. What is far less known is the state of the aquatic facilities and the likely timeframes for their upgrade and replacement.

The State of Aquatic Facility Infrastructure in Australia - Rebuilding our Ageing Public Swimming Pools, a newly released report by Royal Life Saving Society - Australia, was initiated under the guidance of the National Aquatic Industry Committee following anecdotal evidence from members that there was an impending ageing pools crisis, and a deeper understanding of the issue was needed. The report found that significant investment is required to replace, renew or upgrade these pools nearing the end of their life expectancy.

Context of Public Swimming Pools Aquatic facilities are essential for the provision of learn-toswim, water therapy, leisure, physical activity and swimming, which are activities that over five million Australians regularly attend. In addition to these benefits, they are places that create social cohesion. They are an essential service for communities to access now and, most importantly, into the future.

While it is well established that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have a deep connection to water and are known to have participated in swimming and aquatic recreation in Australia for thousands of years, according to historians, Australia’s early public baths were constructed in Melbourne and Sydney.

One of the first was the heated Natatorium Baths in Sydney, built in 1888. Before this time, Australians bathed and swam in the many rivers, ocean beaches, lakes and dams.

Australia’s international reputation for producing successful competitive swimmers also enhanced the interest in swimming pools and grew the community’s acceptance of swimming as a respectable sporting and leisure pastime.

After the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, an influx in the provision of 50-metre pools were built right across the nation, many of which were crowd-funded and managed directly by volunteers, often named as war memorial pools. The 1950s, 1960s and 1970s saw enormous growth in the number of swimming pools constructed across Australia, which has culminated in most of these pools now being at the end of their useful life and requiring an urgent review.

Melbourne 1956 Olympic Pools. Source: Sievers, Wolfgang. (1956). Interior of the Olympic pool, Melbourne http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-160635950

Source: Herald Sun Article: “Campaspe Council: Pools in 7 country Vic Towns to Close” 15th January 2022

Balgo Swimming Pool. Source: Royal Life Saving Western Australia Wran Leisure Centre

Cost to Replace Pools An extensive audit of a statistically relevant sample size of aquatic facilities was conducted under advice from PricewaterhouseCoopers. This audit then classified pools based on age, amount of investment in renewals / upgrades based on publicly available information and then a construction and financial model developed by Leisure Management Excellence and Turner and Townsend was applied to provide an assessment of the likely state and cost of replacing aquatic facilities across Australia built in the 50s, 60s and 70s.

This process found that: •The average Australian public pool was built in 1968 •500 (40%) of public pools will reach the end of their functional lifespan by 2030 •$8 billion is needed to replace those 500 ageing public pools •A further $3 billion will be needed to replace facilities ending their lifespan by 2035

The social health and economic cost of not replacing even 10% of aquatic facilities by the end of this decade could approach $1 billion per year according to multipliers from previous research by PricewaterhouseCoopers and Royal Life Saving.

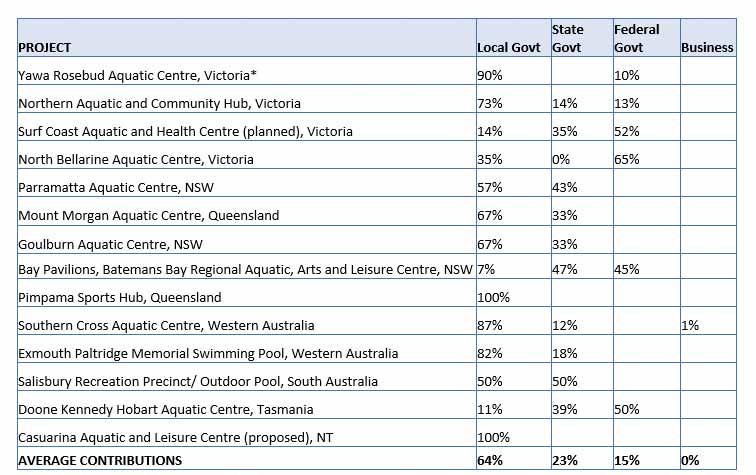

Additionally, the report found that local governments are the primary funder of aquatic facilities and are under extraordinary budgetary pressure currently, so the way in which public pools are funded and maintained needs to be re-examined systematically and across all layers of government.

Other Key Findings The research highlighted that while in wealthy metropolitan areas the rise of privately-owned and operated aquatic facilities is on the rise, in low socio-economic areas and regional areas, privately-owned publicly accessible aquatic facilities are too few to ensure that communities can access safe aquatic locations and learn swimming and water safety skills in supervised environments.

Regional and remote councils seem the most exposed, often providing multiple aquatic facilities across a large area. It has increasingly been these rural communities, but not exclusively, that have been presented with the prospect of pool closures and who have actively resisted.

It is also clear from additional Royal Life Saving research that regional and remote communities are at higher risk of drowning in inland waterways and most benefit from access to swimming and water safety programs, made possible by local public swimming pools in most cases. Closing community pools is inherently very unpopular, consistently aggravating community sentiment and mobilises communities towards involvement in the political process. In order to replace, renew and/or upgrade the 500 pools at the end of their life, significant investment is needed and possibly the exploration of alternative service models for the delivery of aquatic facilities to be identified and implemented. Without both of these, it is likely that the number of swimming pools in Australia will significantly reduce over the coming decade. Most importantly, the opportunities for Australians to access the important social, health and economic benefits of public swimming pools will diminish. The opportunities for healthier lifestyles, social interaction and children learning to swim will be lost.

Horsham War Memorial Pool is a typical 60s-70s public pool Source: Evans, Joyce. (1995). War Memorial Swimming Pool. Horsham, 1995. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-142799427

Additional findings include: •64% of all renewal or new aquatic facility construction is currently financed by local government in Australia •77% of aquatic facilities in regional areas are publicly owned •79% of aquatic facilities located in areas with the lowest

SEIFA (the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Socio-Economic

Indexes for Areas) decile are publicly owned •74% of aquatic facilities located in areas with the highest

SEIFA decile are privately owned •Many regional councils struggle to afford to maintain or replace swimming pools, and increasingly councils are considering closing their pools •Closing community pools is inherently very unpopular and consistently aggravates community sentiment and mobilises communities towards involvement in the political process Impacts Another recent report prepared by PricewaterhouseCoopers on behalf of Royal Life Saving, A Water Loving Nation Free from Drowning - The Role of Learn to Swim report, recently found that: •An estimated 40% of children leave primary school unable to swim the length of an Olympic swimming pool •23% of Australian adults report weak or no swimming ability •Participation in swimming lessons reduces significantly after the age of seven •Those most vulnerable are least likely to access lessons •Barriers include cultural, financial and language difficulties

In addition, the recent Royal Life Saving National Drowning Report 2022 found that drowning deaths increased by 15% compared to the previous year, but 24% compared to the 10year average. Relevant findings include: •Rivers and creeks continue to be the location with the largest number of drowning deaths, accounting for 34% of all deaths •River/creek locations recorded a 65% increase compared with the 10-year average •75% of all drowning deaths were not visitors to the area (0% were overseas visitors in 2021-22) •59% of all drowning last year were in regional areas. Given 86% of the population lives in metropolitan areas, this is concerning

In light of the now historically high drowning rates, the generation of children at risk of missing out on swimming and water safety and this new research about the state of aquatic facility infrastructure, it really is a perfect storm for a number of reasons, including our status as a water-loving nation, our national pride in our competitive swimming success, physical activity, our concept of a fair go and future drowning rates.

130mm x 180mm

Contact info@hydrocarepools.com.au Ph. +612 9604 8396