27 minute read

Reflections

"Create an Altar at Home: A Pandemic Invitation" by Courtney T. Goto

Once in a great while, and if you are lucky, a teaching angel delivers an idea for an assignment that blossoms into learning outcomes you could not have imagined. For me, it began with a series of photos sent by my advisee Erin, a talented visual artist. She had built a mixed-media, multi-level altar in response to Holy Week, explaining the elements and what they meant to her. Inspired by what she had created, I devised a final project for my course, “Doing Theology Aesthetically.” The assignment was to “create an altar that honors a person, season, event, story, or idea with theological, cultural, personal, and/or social significance. An altar is a small, aesthetically marked, sacred space that serves as a focal point for the senses. Reflect on how you might communicate your theme powerfully through multiple elements (color, shape, texture, space). Be creative.”

Advertisement

Inviting students to build an altar at home during the pandemic for a fully remote course had multiple implications. With most religious communities worshipping online or outdoors, students were (and still are, at this writing) separated from and disconnected with the holy place where their community’s altar is located. Tasked with creating a home altar, learners were literally and figuratively “creating with the stuff of their lives”1—with materials that they had on hand or found. The context of learning meant that students worked on their own time, at their own pace, and possibly in the company of members of their household. Rather than being constructed in a classroom and removed because another class was scheduled, their altars “lived” where students lived for however long they felt appropriate and/or practical.

In this brief essay, I wish to reflect on the “ritual labor” that constructing and practicing with an altar revealed.2 Anthropologist Raquel Romberg uses this notion of ritual labor to discuss how Haydée, a Puerto Rican healer, employs a series of ritual steps to transform an ordinary space into a sacred space for a home altar. This “labor” is accomplished through what Romberg calls “spiritual technologies.”3 As a practical theologian, I interpret these technologies as spiritual practices that coax the divine to take up residence in the altar that the healer has constructed (hence the term, “altar-home”). To be clear, I don’t imagine that this is exactly what my students were doing. None of the students belong to religious traditions where building an altar in one’s home is commonly practiced. None are ritual specialists. It might be more accurate to say that creating an altar became the occasion for potentially transforming the space (and therefore the students themselves) by making tangible that which they hold sacred. Building an altar was an opportunity for students to engage in spiritual “work” that was unique to each person and that could only be accomplished by practicing contemplation with their hands, as one can do when making art. I give two examples to inspire you to build your own altar.

The Altar River

Beth built an altar representing the river of her childhood, where she played with her sister for countless summer hours, watching and playing with the flow of water. Comparing the river to a teacher, she wrote, “[The river] created an environment that was prepared from disparate elements (rocks, mountain grade, dirt, leaves, etc.), but from its flexibility and movement an ‘incarnated subject matter’ could arise that was revelatory and powerful for my sister and me as we re-created our world around us.”4 To recreate this river with water continuously running through it, Beth enlisted her children to help with the construction, an unexpected gift to her and their family. By involving them, Beth served as a teacher to her daughters, creating an environment in which they could play with the altar river, changing its course by manipulating its shape. In terms of reflecting theologically, the altar gave Beth an image to work with that came from her own lifeworld. Beth reported, “Using this memory, and the lessons learned from my childhood river as a foundation, I worked to recreate the river as a landscape for how to build and reflect on my own theology.” For example, she described Spirit’s movement as “free” and “mysterious.”

I am struck by an unlikely parallel between Beth’s construction of the altar river and Romberg’s case. The healer incorporates a freshwater aquarium into the altarroom, to “recreat[e] in the space of a living room the natural abode of her Santa, the river [deity].”5 Of course, there’s an important difference. Romberg describes how the altar works by “proxy”—that is, the deity associated with the river takes “ownership” of the representation.6 In contrast, Beth created a river as a symbol to evoke memory and, by association, clarify and elaborate her theology. However, I find it significant that both altars make tangible a distant, even mystical, place outside the home, thereby transforming it. It requires ingenious creativity (or elsewhere I have described it as playing) to bring a sacred, natural element indoors, while expressing what is true to life in the original.7 Using mundane materials on hand, Beth and her family managed to summon the sacred at home, creating a place that was especially meaningful because it was where her childhood, her family, she, herself, and the longed-for divine could meet.

In Honor of Dad

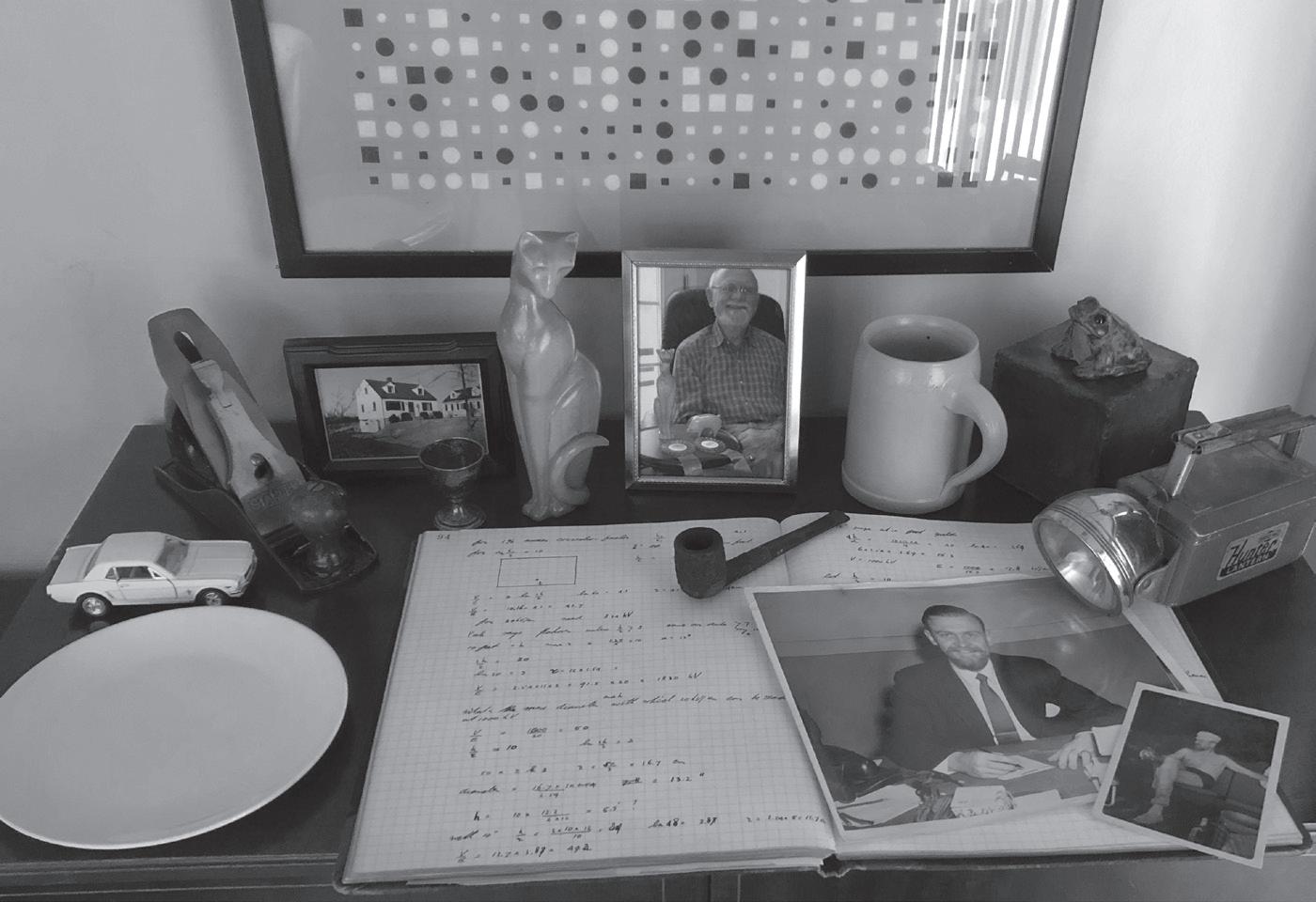

Joann’s altar was a tribute to her father, who had Parkinson’s dementia and was living in a care home. Early in the pandemic, she could not visit in person, and later, only in a limited way because of public health restrictions. She said, “He is still with us but in many ways he feels lost to me.” To create the altar, Joann had gathered artifacts associated with her father—a wood planer from his workshop, one of his pipes, a toy white Mustang, a model like the one he bought and then she drove as a senior in high school, and many other objects. She lovingly narrated the significance of each piece, displaying them against the background of a painting that she made for him. Sadly, Joann’s dad passed two months after she created the altar.

Joann’s altar inspires me to reflect on how building an altar invites presence— creating the conditions for what is otherwise unseen to be seen, but also focusing attention so that the practitioner herself might be present to the holy. Joann made her father present through things or representations of things he touched, used, owned, or even ate. She included a sunny-side-up, fried egg with the whites eaten away, exactly like her dad was in the habit of making and eating. She writes, “The process of building this altar—from curating the items I would include, to where and how I would set it up—made me realize that in a very real way, Dad will never be lost to me. My very body is part of his legacy and I will always carry him with me. I can look at some of these mementos or simply eat an egg to evoke his presence.” Even as her dad was less able to “be there” in the last weeks of his life, the altar brought him to the space and perhaps most importantly, the realization that she had the power to evoke his presence.8

Joann’s memorial altar is perhaps not so different in function to the altarhome studied by Romberg, despite the contrasts. In the Puerto Rican case, the

altar serves as dwelling place for divine-human encounters. Of course, in Joann’s case God does not take residence in the artifacts, but nonetheless the altar serves as a powerful meeting place with her dad when she seeks him. Her altar is sacred in the way that a cemetery is, where one can commune not only with a departed loved one but also with God or the mystery of which the deceased are a part. At her altar, Joann summons not simply Dad but God-with-Dad, who responds to being summoned.

An Invitation

I invite you to build your own altar because the process might allow you to do some spiritual work that you can only do experientially and creatively. Especially during the pandemic and likely after, you might need to contemplate with your hands some of the big issues—life, death, identity, love, and memory—that two of my students took on. By creating the image of the river with her family, Beth strengthened familial relationships and engaged in theological construction. Joann gathered artifacts to honor her father as she prepared for his passing. Both of these altars were deeply personal and proved to be creative labor each student needed to engage. For me, their altars exemplified the important work of concretely imagining the sacred into being in our homes, especially at a time when we feel most vulnerable.

My students have shown how building an altar at home is both doable and potentially a source of spiritual riches. Choose a theme. Use materials that you have on hand. Set up the altar where you can live with it for a while and let it evolve. Involve other people in your household. Engaging in such ritual labor in order to summon the sacred into your home may be among the meaningful and empowering spiritual disciplines you practice during these bewildering, and for many devastating, times.

NOTES

1. Cynthia Winton-Henry, founder of InterPlay.

2. Stephanie Palmié, “Fascinans or Tremendum? Permutations of the State, the Body, and the Divine in Late-Twentieth Century Havana,” New West Indian Guide, 78, no. 3/4 (2004): 229-68. Cited in Raquel Romberg, “Ritual Life of an Altar-Home: A Photographic Essay on Transformational Places and Technologies,” Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft 13, no. 2 (January 1, 2018), 250. https://magic.pennpress. org/home/;; http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lsdar&AN=ATLAiFZK18122400 0649&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

3. Romberg, “Ritual Life of an Altar-Home,” 250.

4. The notion of “incarnating subject matter” comes from Maria Harris, Teaching and Religious Imagination: An Essay in the Theology of Teaching (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1991), 132, 134, 157.

5. Romberg, “Ritual Life of an Altar-Home,” 252. 6. Ibid, 253. 7. Courtney T. Goto, The Grace of Playing: Pedagogies for Leaning into God’s New Creation (New York: Wipf & Stock, 2016). 8. Beth’s altar likewise makes present her sister and the river of her childhood.

Courtney Goto is associate professor of religious education and codirector for the Center for Practical Theology at the Boston University School of Theology where she earned the 2020 Metcalf Award for Teaching Excellence. She is the author of Taking on Practical Theology (Brill 2018) and The Grace of Playing: Pedagogies for Leaning into God’s New Creation (Pickwick, 2016).

"Searching for Beauty: Art in the Midst of Ugly" by Frank Rogers Jr.

In the 1960s, poverty, segregation, and violent social unrest plagued Detroit, Michigan. Redlining separated the races, police raids targeted communities of color, and political corruption kept inner-city ghettoes impoverished and disenfranchised. The riots of 1967 were so severe that the United States military was called in to quell them. Both riots and military were back the following year.

Sixto Rodriguez endured it all. The son of Mexican immigrants, he dwelt in a dilapidated house he had purchased from the government for $50. In response to the violence surrounding him, he made music. Equal parts street poet, social critic, and troubadour holy man, he wrote protest songs and mournful ballads that gave voice to the pain, foretold revolution, and envisioned a world of equity and peace. On street corners and in dive bars, he sang to inspire the subjugated.

The Motown producers who discovered him compared him to Bob Dylan—a gritty, soulful prophet of the times. They recorded two albums, certain the LPs would resonate with socially conscious young people across the country. They were wrong. Radio stations gave them no airtime; sales were abysmal. The setback’s impact on Rodriguez is unclear. The stories that circulated about his suicide are contradictory. Both have him killing himself while performing on stage: in one, he shoots himself in despair, the tyranny so intractable; in the other, he sets himself on fire like a Buddhist monk protesting political oppression. Either way, Rodriguez the man faded from our world.

His music, however, lived on.

Most likely smuggled in by college students, bootleg copies of Rodriguez’s albums found their way into South Africa in the 1980s at the height of apartheid. In a country that had become a police state—with “Blacks” and “Coloured’ displaced into segregated ghettoes, abductions and massacres squashing all opposition— the music spoke to the soul of those mobilizing for liberation. Banned from the government-controlled radio stations, cassette copies were duplicated and shared throughout the resistance. His songs—as “Blowin’ In the Wind” had in the States— became part of the soundtrack that sustained the nonviolent protesters. Rodriguez became a musical icon for the anti-apartheid movement that eventually overthrew the government. When democracy was secured, a CD was commercially published. The music already saturating the people, it sold more albums than the Beatles, Elvis, or the Rolling Stones. In his own homeland, on the other side of the world, Rodriguez was long forgotten, if ever known. In South Africa, he was a rock star. His music helped set a people free.

* * *

Pain permeates our planet. Violence, in its many forms, continues to rip away at our wounded world. All these decades later racism still afflicts Blacks in the United States. It would be easy to succumb to despair, to harden our hearts at the heaviness of it all, to deaden our spirits in resignation before powers that appear impregnable. God’s heart, however, remains soft; God’s spirit pulsates with hope and resilience. Like a river of creative vitality, God’s spirit dwells as a lifeforce that infuses all of creation. What Hildegard of Bingen called “the greening power of God,” this sacred current, flowing through everything, is restorative—it invigorates the flourishing of life.

This life-force is present within suffering as well. God sees the brokenness in our world, is moved by the pain, and companions all who are afflicted, aching to heal wounds, buoy hope, embolden courage, and inspire a flourishing sustained by societies of justice, equity, and peaceful co-existence. When Sixto Rodriguez faces the suffering in his world and accesses the creative life-force to make music of hope and peace, he bears witness to and participates in God’s irrepressible power to restore life in the midst of death. The art he creates is sacred. It pulsates with promise. And it takes on a life of its own—inspiring others even on the far side of the globe.

And Then …

In the late 1990s, a quarter century after Rodriguez recorded his albums, two South African fans joined forces to uncover the true story of Rodriguez’s death. Knowing nothing about him—not even where he was from—they followed clues from his song lyrics and emailed musical professionals around the world. No one outside of South Africa had ever heard of him. After hundreds of queries, they stumbled upon his former producer, now living in LA. When they asked him how Rodriguez had died, the producer was taken aback. Rodriguez was not dead: he was still in Detroit, living in the same decrepit tenement building, without a car, TV, or computer, making ends meet as a day-laborer, and utterly oblivious to his rock-star status an entire world away.

The fans arranged a concert tour and invited him to South Africa. Rodriguez expected to perform for a few enthusiasts in a jazz club or two. He arrived to a hero’s reception. Limousines greeted him at the airport; billboards boasted his image; fans flocked for autographs, some even wanting autographs across tattoos of him on their torsos. At six sold-out concerts of 30,000, people sang with him word for word the songs that had sustained their dreams for a better world. For ten days, he toured the townships and countryside, playing his music of peace and nonviolent revolution. “Gandhi with a Guitar” they called him. Little did they know—back home, he no longer owned one. The promoters had to hustle up a professional acoustic for the tour. Rodriguez took right to it. Cradling it like an old friend, he strode boldly to the mic in the packed arena. Thousands of screaming fans awaited him. Rodriguez beheld their adoration. Then he offered them his first words,

“Thanks for keeping me alive.”

* * *

Faith in the face of suffering is an artistic enterprise. Racism, poverty, the abuse of a child, the subjugation of a people—these cry out for an aesthetic response. To be sure, they also demand analytical reflection to root out their causes and ethical imperatives to guide transformative response. Yet suffering is not only a rational distortion and a moral affront; it is ugly. Violence, molestation, and torture are grotesque. They make us wince. They break our hearts. Life’s sacred right to flourish is being marred. Beauty is violated.

Karl Barth understands beauty to be an attribute of God. God’s beauty is God’s inherently radiant glory—the shining that speaks for itself that God is present in all of God’s fullness. When life flourishes, it is beautiful and a reflection of divine beauty; when life is disfigured, it is horrid, and God’s beauty is befouled. People of faith are called to be artists—to face the pain of the world feelingly, to be moved by its suffering, to ache for its healing, and to rise up, fused with God’s restorative power, to coax life out of death, beauty out of ugliness. This not only keeps our own souls alive, it transforms the shadows of suffering into the radiance of God’s glory, a glory that will ripple out and one day fill the earth as waters cover the sea (Habakkuk 2:14).

And Then … II

In 2006, a twenty-six-year-old Swedish freelance news-reporter, the son of Algerian immigrants, traveled throughout the southern hemisphere in search of stories to produce. Wandering into a Cape Town record store, Malik Bendjelloul met one of the men who had researched Rodriguez’s death, had found him alive, and had brought him to South Africa as the anti-apartheid rock star he had no idea that he was. Malik was so moved by the story, he decided to direct a documentary.

By all accounts, a young man of self-effacing but infectious enthusiasm, with an elfish charm that befriended everyone he met, this first-time filmmaker raised the funds, scouted locations, and recruited each person involved—including Rodriguez himself, who still lived in the same tenement, still scrabbling as a day-laborer.

For five years, Malik’s indefatigable spirit willed the picture into being. When he ran out of funding, he drained his own accounts; when he could no longer hire personnel, he filmed the last scenes on his iPhone, learned how to edit and score off his computer, and drew his own illustrations.

Searching for Sugar Man was a film that embodied and celebrated the indomitable power of art, even in ways oblivious to the artist. It was also a surprise global sensation. It won the Grand Jury Award at Sundance, a BAFTA in London, and dozens of first-place finishes in film festivals from Moscow to Melbourne, Toronto to Durban. With the film’s success, interest in Rodriguez’s music surged. He played concerts in conjunction with film festivals; he gave scores of interviews alongside the director; his albums were re-released to wide acclaim. Just as his producers had predicted, Rodriguez’s music touched people around the world. It had only taken thirty-five years. Malik’s movie made it possible. In 2013, Searching for Sugar Man won the Academy Award for Best Feature Documentary. * * *

This is our confidence: as we face life’s brutalities with creative vitality, as we rise up as faithful artists, we not only bear witness to the presence of God in solidarity with those who are suffering, we bring beauty into the world that lives on beyond us. The art of our faith ripples out. It touches hearts, ignites hope, and inspires commitments to healing and liberation. The songs we send into the world are choruses in the cosmic symphony of life, the sacred music that echoes forth inviting all of creation into its restorative rhythms. Through beauty, the ugliness of suffering is transformed; divine glory radiates throughout the world. * * *

And Then … III

Barely a year after the Academy Awards, Malik Bendjelloul left his apartment and walked to a Stockholm subway station. Still pondering a variety of projects to take on, he gave no indication of his plans to his family or friends. Stunning all who knew him, the eminently likable storyteller entered the station and threw himself in front of a speeding train. He left no note. The silence of his death yields no explanation.

Rodriguez was informed, the following day, minutes before a concert. He lit a candle backstage, cradled his guitar, and went out to share the news with his capacity audience. Then he did what he knew how to do.

For those who wail out loud, and for those who suffer in silence, for Detroit, South Africa, the world, for Malik, Rodriguez played his music. * * *

The turmoil that leads one to suicide is agonizing. It is excruciating to face. Despair is ugly.

Unlike Rodriguez, Malik’s story does not have an inspirational dénouement—a surprise appearance of one thought dead expressing to his fans, “Thank you for keeping me alive.”

The dénouement is left to us. We are called to face the tragic feelingly—to be moved by its suffering, to ache for its healing, and to rise up, with the spark of the sacred, in creative response. Holding ugliness with compassion is, itself, beautiful. It is, indeed, what keeps us alive in the midst of the struggle.

Frank Rogers Jr. is the Muriel Bernice Roberts Professor of Spiritual Formation and Narrative Pedagogy and the co-director of the Center for Engaged Compassion at the Claremont School of Theology. Also a spiritual director and retreat leader, he is the author of Practicing Compassion and Compassion in Practice: The Way of Jesus.

"Theater as Acts of Uncrippling" by Dessa Quesada-Palm

Artists dream and imagine. They intuit a sense of beauty, of goodness, and of the ideal. So when the world around them falls short of this vision, artists bear witness to an undeniable yearning. They confess, they plead, they intercede. Their art becomes an integral expression of their life’s mission.

A melancholia had begun to set in as the reality of an end to things was spoken in hush. But then the Spirit moved and this question was dropped: “Is this theater work something you want to continue to do?” The room exploded into euphoric shrieks of jubilation as the youth realized this marked not the end, but in fact the beginning. The moment was December 18, 2005. The youth had gathered in our home to reflect on this prime experience and to break bread. It was the birthing of the Youth Advocates Through Theater Arts.

Exactly a month before I had co-facilitated a theater workshop in Dumaguete City, Negros Island, for high school and college students from various schools throughout the Visayas, the central islands of the Philippines. The three-day workshop focused on child trafficking for sexual purposes—the Philippines has been declared a global hotspot for child trafficking1—and was part of a nationwide campaign organized by ECPAT (End Child Pornography, Prostitution and Trafficking) and PETA (Philippine Educational Theater Association). After the workshop I continued to work with the thirty participants, and we mounted a theater performance on child trafficking at the city’s public park on December 9. The skits were based on case studies from our own region of the Visayas. The public performance fulfilled the project deliverables, and the youth were to have parted ways. But God had different plans.

The energy of the youth was undeniable and urgent, and closing a creative space that was built in the course of a few weeks because of an imposed project timeline seemed wrong. Yet, there were no more institutional resources available. In this Kairos moment the youth rose up to mark a new beginning, a beginning that resonated with my own life experience as a teenager.

For most of my childhood, I lived in the shadows of my tiny world, letting the physical debilitation of asthma and a rheumatic heart disease constrict my life. In a form of victim power, a potent narrative would intersect with my diminished motivation in going to school. In many ways my first, if unconscious, acts of roleplaying came when I provoked asthma attacks on mornings when the prospect of going to school was not enticing. That habit quickly dissolved after the first day of the Teen Theater Workshop I attended when I was thirteen. The workshop, facilitated by PETA, combined a process of creative release and self-discovery, collaboration with peers and improvisation, exploration of the role of theater in society, exposure trips to unfamiliar social contexts, an original artistic production created by the participants, and an echo workshop, where trainees learn to teach what they’ve been taught and begin to conduct workshops for other young people. Each day during the workshop, I resolved never to get sick again so I could complete the program. It was a Spirit-led pivot that changed the course of my life. I always refer to those six weeks as my rebirth, when my life was catapulted to a new, awakened sense of who I am and what I could be with and for others.

The story of Jesus healing the woman who had been crippled in Luke 13: 11-13 resonates with the Spirit-led pivot to rebirth that has transformed my life and the lives of so many others.

And just then there appeared a woman with a spirit that had crippled her for eighteen years. She was bent over and was quite unable to stand up straight. When Jesus saw her, he called her over and said, “Woman, you are set free from your ailment.” When he laid his hands on her, immediately she stood up straight and began praising God (New Revised Standard Version). I want to reflect on the spirit crippling many young people, including me, in my youth.

In laying down the framework of a theater workshop, we often foreground it with the premise that people are inherently creative. Created in the image of God, humans are endowed with the power to think, to express, to create. And yet this gift of creativity and its immense potential can be buried in the mire of fear and self-doubt or in suppressive environments and structural deprivation. Some may say these layers are merely circumstantial, the result of poor decisions or ill luck to be born into poverty or on the margins. But that would gloss over the systemic dimensions of oppression.

I grew up under martial law during the reign of authoritarian president Ferdinand Marcos.2 My peers and I experienced the clear interplay between militarism and the promotion of cultural values that perpetuate subservience.

Militarism thrives on ordered ways in status quo-defined molds of behavior and thinking. Where obedience to figures and symbols of authority is the desired norm, creativity, critical thinking, and spontaneity are powerfully suppressed. This often translates to parallel relationships in family and school settings, where the parents’ or teachers’ approval is regarded as the coveted goal of each child, and subservience is an applauded, default response to authority. In this context, young people are subjected to infantilizing standards of good behavior and must conform to readymade scripts or be regarded as deviant. Under such pressure, many youth enter into a crippling position of being passive recipients of a narrative imposed on them.

When Jesus calls over that woman at the synagogue and declares, “Woman, you are set free from your ailment,” the emancipation that emerges from this declaration leads to dramatic transformation in the woman physiologically, socially, and spiritually. Three vital aspects emerge in this story. First, despite her pained condition, the woman was present; she found the time and mustered the will to be in a place to encounter Christ. Second, when Jesus beckons her, the invitation that is offered is received. Third, with the declaration of emancipation, Jesus opens a sacred opportunity for healing, an act of disruption, a call to break from a script that has crippled one’s life potentials and capacities. The result of this disruption is heightened empowerment that translates into acts of deepened faithfulness. So, for instance, the woman stands up straight and begins to praise God.

God’s invitation to transformative spaces comes not only in the context of synagogues and churches. Junsly Kitay was sixteen when he joined our 2005 workshop. His participation was arranged with Kalauman Development Center, a church-related organization that provided educational support to children living in difficult circumstances. The eldest of four children, Junsly came from an economically disadvantaged community near the city’s port that was beleaguered by the illegal drug trade in crystal meth, locally known as shabu. His mother worked as a laundry washer and his father as a mechanic, making ends meet for the family despite all the odds. But his father was lured into the lucrative drug trade, which led to his arrest, release, and a cycle of recidivism. According to Junsly, many young people from his neighborhood get entangled in the drug trade where they are easily recruited as runners. He says that if it were not for his newfound sense of mission and love for theater, he would, like many of his peers, be in the drug trade, in prison, or dead. It is a tragic script played out by youth in his community that Junsly was able to rewrite. As a result of his creative awakening and newfound sense of agency, he began to examine his options and to recast his life.

Junsly’s transformation, and that of so many others in our Youth Advocates Through Theater Arts program— which through the generosity of mission partners and friends remains an active ministry—reminds me of my own journey. A woman bent and distorted physically for eighteen years now stands straight and with ease because of Christ’s healing; she is now more capable of engagement. In our theater practice, we encourage performers to find their own “actor’s body,” typically pertaining to a state that holds a balance of calm and focus: a lengthened spine, relaxed shoulders and neck, soft gaze, feet hip-width apart. It is an embodiment of confidence and readiness, a state that prepares the actor for the task ahead, to tell a story with truth and integrity.

Transforming moments for our young creatives often happen in an ordinary training room, when the Holy Spirit inhabits the space and moves through games, storytelling, music, movement, visual arts, literature, drama. In theater, God provides an opportunity for one to take, in the words of Viola Spolin, “a vacation from oneself and the routine of everyday living.”3 Or, as Augusto Boal names it in Theater of the Oppressed, theater becomes a rehearsal for change, a change that is physical, social, and spiritual.4

Artists dream and imagine. They intuit a sense of beauty, of goodness, and of the ideal, of God’s vision for the created world and all its inhabitants. And so, when the world around them falls short, artists bear witness to an undeniable yearning. They confess, they plead, they intercede, they are spiritually empowered, and they empower. This is a vital root of advocacy: the work of young people telling their stories through theater, imploring communities to listen, to feel, and to act in ways to change the situation. This is their way of praising God and inviting people to heed the Lord’s prayer, that God’s “will be done on earth as it is in heaven.” v

NOTES

1. https://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/shipments-children (accessed December 16, 2020). 2 Ferdinand Marcos declared Martial Law in September 21, 1972, amidst growing social unrest. He was ousted in 1986 by what was popularly called the People’s Power Revolution. 3 “Playing a game is psychologically different in degree but not in kind from dramatic acting. The ability to create a situation imaginatively and to play a role in it is a tremendous experience, a sort of vacation from one’s everyday self and the routine of everyday living. We observe that this psychological freedom creates a condition in which strain and conflict are dissolved and potentialities are released in the spontaneous effort to meet the demands of the situation” (Neva L. Boyd, Play, a Unique Discipline, as cited in Viola Spolin, Improvisation for the Theater [Northwestern University Press, 1963], 5). 4. This term is popularized by Augusto Boal, who wrote Theater of the Oppressed (Routledge, 1973), detailing his work in using theater for the marginalized communities in Sao Paolo in Brazil and in other parts of South America.

Dessa Quesada-Palm is founding artistic director of the Youth Advocates Through Theater Arts and senior artist-trainer of the Philippine Educational Theater Association (PETA). She received a BA in economics at the University of the Philippines and a master’s in international relations at the New School for Social Research, New York City, as a Fulbright scholar.