Advances Calibre Essay Prize

When the Calibre Essay Prize, now in its fourteenth year, closed on January 15, there was an oddly shaped, menacing elephant in the room. Few people were aware of the coronavirus, though it had been detected in China the previous month. Not until January 25 was the first case diagnosed in Australia. By the middle of March, of course, the full extent of the catastrophe was apparent, with untold consequences for society, the economy, and the arts. For Calibre, the theme uppermost in people’s minds was undoubtedly climate change and the recent bushfires that had ravaged large part of Australia – some of them previously unaffected by bushfires. Then there was the customary range of subjects: literary criticism, philosophical speculation, travel writing, personal memoir, childhood memories, and domestic subjects, often poignant, sometimes harrowing. Next year, we suspect, the balance will be upset by something called the pandemic. This year we received almost 600 copies from twenty-nine different countries – by far our largest field to date. The judges this year were J.M. Coetzee (Nobel Laureate), Lisa Gorton (poet, novelist, and essayist), and Peter Rose (ABR Editor). Often, the two winning Calibre Essays are very different, reflecting the multifarious nature of the field. Last year, for instance, Professor Grace Karskens, the overall winner, introduced us to the remarkable Nah Doongh, one of the first Aboriginal children to grow up in conquered land, while the second prize went to Sarah Walker’s highly personal account of an abortion. (Sarah, who went on to become one of the first ABR Rising Stars, has a wonderful essay in this issue on the loss and commemoration of her mother at the start of the pandemic: see page 20.) This year it’s very different: both essays deal with aspects of gender, difficulty, health, overcoming, becoming – the endless stages of self-realisation. The winner of this year’s Calibre Essay Prize is ‘Reading the Mess Backwards’ by Yves Rees, a writer and historian who teaches at La Trobe University. Dr Rees has published widely on Australian gender, economic, and transnational history, and also writes on transgender identity and politics. ‘Reading the Mess Backwards’ is an absorbing account of ‘trans becoming’ in a personal context, addressed without rancour or self pity. It explores how we come to understand and perform our gender in a world of restrictive binaries and male dominance. Yves Rees told Advances: I am honoured to be awarded the Calibre Essay Prize. In my essay, I’ve sketched the kind of narrative I hungered to read: a story of trans becoming that digs into the messiness of bodies, gender and identity. My hope is that, as such stories proliferate, we will all – men and women, cisgender and trans – be liberated from the prison of patriarchy, with its suffocating gender binary.

The recognition afforded by the Calibre Essay Prize is an important step in that struggle.

Our runner-up this year is Kate Middleton, the Sydney poet and critic, who began contributing to the magazine while still a student almost twenty years ago (one of her first reviews appears in From the Archive on page 68). Kate’s essay, entitled ‘The Dolorimeter’, is a riveting meditation on ill health over many years. We look forward to publishing it in the next issue. In addition, the judges commended five other essays. They are Sue Cochius’s ‘Mrs Mahomet’, Julian Davies’ ‘A Small Boy and Cambodia’, Mireille Juchau’s ‘Only One Refused’, Laura Kolbe’s ‘Human Women, Magic Flutes’, and Meredith Wattison’s ‘Ambivalence: The Afterlife of Patrick White’. We look forward to publishing some of these essays in coming months. ABR gratefully acknowledges the generous support from Mr Colin Golvan AM QC and Peter and Mary-Ruth McLennan, whose donations make the Calibre Prize possible in this form. We look forward to presenting the Calibre Prize for a fifteenth time in 2021.

The lurking horrors

Most poets’ centenaries go unnoticed in this country, but Gwen Harwood’s feels different. When she died in Hobart in 1995, aged seventy-five, she was ‘undoubtedly Australia’s most loved poet’, as Peter Porter, not exactly unpopular himself, noted in an illuminating review of her posthumous Collected Poems (University of Queensland Press, 2003). Most loved? So Harwood perhaps remains twenty-five years after her death, certainly among Australian poets. When ABR invited a number of them to contribute to a special podcast tribute, the response was swift. Readers include old acquaintances of Gwen’s – Stephen Edgar, Andrew Taylor, Chris Wallace-Crabbe, Andrew Taylor, Stephanie Trigg, our Editor, whose first collection she launched in verse back in 1990 during a rare visit to Melbourne (her travels were few, and she never left Australia; perhaps, like Emily Dickinson, she felt, ‘To shut our eyes is Travel’); her biographer, Ann-Marie Priest (whose long-awaited book has been pushed back to 2021 because of the pandemic); her editors Alison Hodinott and Gregory Kratzmann; and composer–collaborator Larry Sitsky, who reads ‘Night Music’, Gwen’s 1963 response to his music. Porter’s review – well worth revisiting (TLS, 9 May 2003) – is illuminating. He notes that Harwood’s poetry is ‘suffused with music’ and rates her as having ‘as natural a feeling for tetrameter as Auden’ – high praise coming from him. Then there is this classic Porterism: Harwood’s regular metric and rhymes swathe the lurking horrors in suburban reasonableness. She might have found another way A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

1

Australian Book Review June–July 2020, no. 422

First series 1961–74 | Second series (1978 onwards, from no. 1) Registered by Australia Post | Printed by Doran Printing ISSN 0155-2864 ABR is published ten times a year by Australian Book Review Inc. Studio 2, 207 City Road, Southbank, Vic. 3006 This is a Creative Spaces managed studio, Creative Spaces is a program of Arts Melbourne at the City of Melbourne. Phone: (03) 9699 8822 Twitter: @AustBookReview Facebook: @AustralianBookReview Instagram: @AustralianBookReview www.australianbookreview.com.au Editor and CEO Peter Rose – editor@australianbookreview.com.au Deputy Editor Amy Baillieu – abr@australianbookreview.com.au Assistant Editor Jack Callil – digital@australianbookreview.com.au Business Manager Grace Chang – business@australianbookreview.com.au Development Consultant Christopher Menz – development@australianbookreview.com.au Poetry Editor John Hawke (with assistance from Judith Bishop) Chair Sarah Holland-Batt Treasurer Peter McLennan Board Members Graham Anderson, Ian Dickson, Rae Frances, Colin Golvan, Billy Griffiths, Sharon Pickering, Robert Sessions, Ilana Snyder ABR Laureates David Malouf (2014) | Robyn Archer (2016) ABR Rising Stars Alex Tighe (NSW, 2019) | Sarah Walker (Vic., 2019) Editorial Advisers Frank Bongiorno, Danielle Clode, Clare Corbould, Des Cowley, Mark Edele, Kári Gíslason, Tom Griffiths, Sue Kossew, Johanna Leggatt, Bruce Moore, Rachel Robertson, Lynette Russell, Alison Stieven-Taylor, Alistair Thomson, Peter Tregear, Ben Wellings, Rita Wilson Monash University Editorial Interns Perri Dudley, Elizabeth Streeter Volunteers Alan Haig, Margaret Robson Kett, John Scully

Subscriptions One year (print + online): $95 | One year (online only): $60 Subscription rates above are for individuals in Australia. All prices include GST. More information about subscription rates, including international, concession, and institutional rates is available: www.australianbookreview.com.au Email: business@australianbookreview.com.au Phone: (03) 9699 8822 Acknowledgment of Country Australian Book Review acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the Kulin Nation as Traditional Owners of the land on which it is situated in Southbank, Victoria, and pays respect to the Elders, past and present.

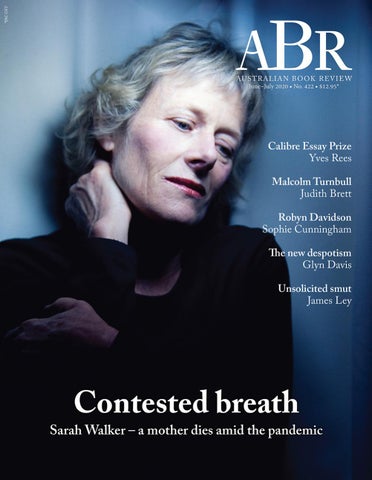

Cover Image Julie Walker, 1955-2020 (photograph by Sarah Walker). Cover design Jack Callil Letters to the Editor We welcome succinct letters and online comments. Letters and comments are subject to editing. Correspondents must provide contact details: letters@australianbookreview.com.au Publicity & Advertising Amy Baillieu – abr@australianbookreview.com.au Media Kit available from our website. Contributors The ❖ symbol next to a contributor’s name denotes that it is their first appearance in the magazine. Environment Australian Book Review is printed by Doran Printing, an FSC® certified printer (C005519). Doran Printing uses clean energy provided by Hydro Tasmania. All inks are soy-based, and all paper waste is recycled to make new paper products.

Image credits and information Page 27: Surveillance screens, former Stasi prison, Hohenschönhausen Memorial, Berlin (Novarc Images/Christian Reister Alamy) | Page 57: Elizabeth Taylor with Dame Margot Fonteyn at London Airport,1958. File Reference #1014 005 THA © JRC /The Hollywood Archive. All Rights Reserved. Image ID: PM4K12 2 A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

ABR June 2020 LETTERS

4

Jenny Hocking, Roger Rees, Elisabeth Holdsworth, Bronwyn Mills, Lindy Warrell, Iradj Nabavi, Wayne Eaton, Tom Gutteridge

POLITICS

8 10 11 14 15 42 43

Judith Brett Glyn Davis Frank Bongiorno Benjamin T. Jones Kieran Pender Alex Tighe Lyndon Megarrity

A Bigger Picture by Malcolm Turnbull The New Despotism by John Keane Becoming John Curtin and James Scullin by Liam Byrne Democratic Adventurer by Sean Scalmer Law in War by Catherine Bond Net Privacy by Sacha Molitorisz Trials and Transformations, 2001–2004, edited by Tom Frame

POEMS

16 26 34

Stephen Edgar Gwen Harwood Jaya Savige

‘Dawn Solo’ ‘Carnal Knowledge I’ ‘Back to the Fuchsia’

LITERARY STUDIES

17 18 44

James Ley Sophie Cunningham Dan Dixon

The Trials of Portnoy by Patrick Mullins On Robyn Davidson by Richard Cooke Spinoza’s Overcoat by Subhash Jaireth

ESSAY

20

Sarah Walker

‘Contested breath: The ethics of assembly in an age of absurdity’

MEMOIR & BIOGRAPHY

24 45 46 47 49

Ronan McDonald Jacqueline Kent Susan Varga Peter Craven Tali Lavi

Parisian Lives by Deirdre Bair Radio Girl by David Dufty Untethered by Hayley Katzen Apropos of Nothing by Woody Allen Daddy Cool by Darleen Bungey

HISTORY

25

Sheila Fitzpatrick

The Ratline by Philippe Sands

FICTION

28 29 31 31 32 33 35 35

Naama Grey-Smith Nicole Abadee Declan Fry Laura Elizabeth Woollett Lisa Bennett Margaret Robson Kett Rosalind Moran Chloë Cooper

Rise & Shine by Patrick Allington A Treacherous Country by K.M. Kruimink Elephants with Headlights by Bem Le Hunte The Rain Heron by Robbie Arnott Smart Ovens for Lonely People by Elizabeth Tan Three new fantasy novels for younger readers Fauna by Donna Mazza State Highway One by Sam Coley

CALIBRE ESSAY

36

Yves Rees

‘Reading the mess backwards’

LANGUAGE

40

Amanda Laugesen

‘Coronaspeak: Tracking language in a pandemic’

COMMENTARY

41

Robert Wood

‘Literary journals and freedom of expression’

SOCIETY

50 51

Kerryn Goldsworthy A Lasting Conversation, edited by Susan Ogle and Melanie Joosten Grandmothers, edited by Helen Elliott Zora Simic The Better Half by Sharon Moalem

ENVIRONMENT

52

Natalie Osborne

POETRY

53 55 56

Luke Beesley Three new poetry collections Geoff Page A Gathered Distance by Mark Tredinnick The Mirror Hurlers by Ross Gillett Chris Wallace-Crabbe A Little History of Poetry, edited by John Carey

ARTS

58 59 60 61 63 64 65 66 67

Ian Dickson ‘A night at the opera’ Tim Byrne Take Me to the World Nicholas Tochka ‘Government versus artists during the Spanish Flu’ Jordan Prosser Hearts and Bones Meg Foster The Whole Picture by Alice Procter Luke Stegemann The Stranger Artist by Quentin Sprague Jane Sullivan Intrépide by Clem Gorman and Therese Gorman Tali Lavi Cock, Cock ... Who’s there? Ben Brooker The Plot Against America

FROM THE ARCHIVE

68

Kate Middleton

The Citizen’s Guide to Climate Success by Mark Jaccard

Of a Boy by Sonya Hartnett A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

3

to shock her contented nation, but she chooses to outfit her demons with the reassurance of perfected form.

Porter, who regarded Harwood as ‘a great thinker in poetry, very much the Empson “argufier”’, rightly considered her neglect overseas ‘deplorable’. What more did they want in London or New York? At the time, Porter’s closing remarks may have seemed a little surprising, even heretical to some – but not in 2020, when Harwood’s wit, emotional range, and metrical gifts seem ever more treasurable. Porter wrote:

‘Love Songs’. She declined. Years later, she remarked to Greg Kratzmann, ‘What other kind of knowledge is there?’ We’re delighted to be able to reprint ‘Carnal Knowledge I’ on page 26.

A nation of thinkers

What authors need most – especially right now – is a sense of security: the freedom to advance a major project with the kind of financial ease that the rest of the community takes for granted. Right now, with a noticeable tightening in the publishing sector and the postponement of many trade It looks, after all, as if lovers of Australian titles, this security is in short supply. poetry have been getting their messages Which makes the Copyright Agency’s crossed. Gwen Harwood turns out to be Fellowships for two creative writers and one the most accomplished poet the country visual artist even more significant. As Kim produced in the twentieth century. Williams, Chair of Copyright Agency has stated, ‘We’re really pleased to be able to ofA coming episode of the ABR Podcast fer even more support for our members who (due to be released on June 4) features work so hard to make Australia a creative some of Harwood’s most celebrated poems, nation as part of a broader aspiration to be including ‘The Twins’, ‘Dialogue’, and ‘Suba nation of thinkers.’ Gwen Harwood urban Sonnet’. The podcast concludes with Past Fellows have included James ABR Laureate Robyn Archer’s sung version Bradley, Kathryn Heyman, Melissa Luof the latter poem. cashenko, Stephen Orr, and Jeff Sparrow. Advances liked this anecdote about another of the featured Each Fellowship – two of them literary, one artistic – is poems, ‘Carnal Knowledge I’. When The Australian published worth $80,000. Applications for close on 29 June 2020. More it in 1972, an editor asked Harwood to change the title to information is available on Copyright Agency’s website.

Letters A want of disclosure

Dear Editor, In his response to my article, ‘At Her Majesty’s Pleasure: Sir John Kerr and the Royal Dismissal Secrets’ (ABR, April 2020), the Director-General of the National Archives, David Fricker, acknowledges that there have been ‘unacceptable delays’ in dealing with access requests, accepts that the National Archives has spent close to a million dollars contesting my legal action in the ‘Palace letters’ case, and yet claims the National Archives is a ‘pro-disclosure organisation’ (ABR, May 2020). I address just one part of Mr Fricker’s response to my article, which discusses this legal action seeking access to the secret Palace letters, between the Queen and the Governor-General Sir John Kerr, relating to Kerr’s 1975 dismissal of the Whitlam government. While conceding the historical significance of and the great public interest in the Palace letters, Mr Fricker writes that they are ‘personal’ records and are therefore governed by their own access conditions agreed to by the National Archives with Kerr, which must be adhered to. To do otherwise, Fricker says, would constitute a ‘massive breach of trust’. In denying public access to these historic letters, the National Archives argues that it is merely upholding the condi4 A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

tions for access specified by the depositor, Sir John Kerr, as it must for all personal records. As David Fricker describes, the Palace letters were deposited after Kerr left office by the Governor-General’s official secretary, Mr David Smith, ‘as Sir John Kerr’s agent with the Australian Archives in August 1978. In accordance with Kerr’s instructions, their release would occur sixty years (later changed to fifty) from the end of Kerr’s appointment, “only after consultation with The Sovereign’s Private Secretary of the day and with the Governor General’s Official Secretary of the day”.’ That parenthetical ‘later changed to fifty’ neatly masks two critical facts about Kerr’s instructions that Mr Fricker fails to mention, and without which it might appear that Kerr himself had changed the conditions of access – not an unreasonable conclusion since, according to Fricker, the letters must be dealt with ‘in accordance with Kerr’s instructions’. In fact, the changes to Kerr’s conditions were made after Kerr’s death, and on the instruction of the Queen. The access conditions currently over the Palace letters are not those set by Kerr. There were two changes made to Kerr’s conditions, the second of which was the most significant and which Mr Fricker also fails to mention: Kerr’s requirement that the letters only

be released after ‘consultation with’ both the Sovereign’s Private Secretary and the Governor General’s Official Secretary was changed to now require the ‘approval of’ both the Sovereign’s Private Secretary and the Governor General’s Official Secretary. It is this change that has given the monarch an effective final veto over their release, potentially indefinitely. David Fricker’s insistence that ‘[s]tewardship of personal records requires a respect for the depositor’ is impossible to reconcile with these definitive changes to Kerr’s access conditions over the Palace letters, made after his death and on the instruction of the Queen. Jenny Hocking, Kensington, Vic. Dear Editor, I read with interest David Fricker’s ‘Questions of Access’ defence of the National Archives (ABR, May 2020). Unfortunately, this response reads like the usual cover-up and evasion as to what happened when a twice-elected prime minister was dismissed by the monarch’s Australian representative. In her article ‘At Her Majesty’s Pleasure’, Professor Jenny Hocking questioned the extent of the monarch’s control over disclosure by the National Archives of the dismissal letters. This is the focus – not whether tens of millions of people access services of the National Archives. The Archives’ Director-General’s statement that ‘the facts will speak for themselves’ is an example of evasion. Surely more openness could direct energy towards exposing the unnecessary deceits of everyday politics, which in this case allows the monarch to maintain control over a most significant event in Australian history. In this matter, the criteria as to what is proprietary and lawful is still determined by the monarch. The Australian public’s right to know remains gagged. No matter how long it takes, the dismissal letters will eventually be revealed. Let’s end this monarchical cover-up now. Roger Rees, Goolwa, SA

This worried world

Dear Editor, I commend ABR on the gutsy decision to create the Behrouz Boochani Fellowship. Australia Council, please note! And I offer my heartiest congratulations to the 2020 recipient, Dr Hessom Razavi. His first offering could not be more timely. His modestly titled article, ‘Notes on a Pandemic’, is remarkable (ABR, May 2020). I have rarely read such an insightful work covering so many areas concerning us at this time. There is the history of the outbreak, the painfully slow gathering of evidence as this beast spread itself around the world, firsthand accounts from those on the frontline, epidemiological considerations, informed speculation about the future, and a detailed explanation of how Covid-19 behaves in the body – all presented in an engrossing fashion. Rereading the essay several times, I was struck by how little there was of Dr Razavi in the essay. No grandstanding here – he shines the spotlight on others. But we do learn that he and his wife (also a doctor) are about to welcome a daughter into this worried world. She will be blessed by having such brave parents. I look forward to reading more of Hessom Razavi’s work. Elisabeth Holdsworth, Morwell, Vic.

Dear Editor, What a sane and moving commentary on the situation engendered by the Covid-19 pandemic. I listen to the ABR Podcast as a US citizen living in Costa Rica, where the response was immediate, very community-minded, and effective. To date there have been only seven deaths. Friends with other conditions that need attention are now crowded out by huge numbers of Covid-19 patients. A small percentage are hospitalised, and a smaller proportion of those are in the ICU. What the disease has also done is reveal the threadbare responses of so many countries, the United States being by far the worst. Those of us in or from the so-called First World have been living in a world where compassion is deemed less and less necessary and where community bonds are fragile. Now we are paying the price. If only we could change our ways, oust the corrupt, ignorant, cruel politicians and work towards a better world. In the case of the United States, that will be an uphill battle. As for Hessom Razavi’s comment about US sanctions: do not expect any humanity on the part of the present US government. Its leader does not lead, and his minions are fanatics with no perceptible mercy. Bronwyn Mills (online comment) Dear Editor, Thanks for an absolutely marvellous article. It is the best thing I’ve read on this topic. Lindy Warrell (online comment) Dear Editor, Why is Dr Razavi so critical of the Iranian government while saying nothing about US sanctions against that country? The Iranian government should certainly be blamed, but we should be even-handed. Dr Razavi also doesn’t commnent on why the situation in the United States, as elsewhere, is much worse than in Iran? Iradj Nabavi (online comment)

Cart before the horse

Dear Editor, I completely agree with Peter Mares’s assessment of Liz Allen’s book The Future of Us: Demography gets a makeover (ABR, May 2020). While this passionately argued and engaging polemic examines an aspect of Australian political and economic life from an interesting angle, Allen does ‘put the cart before the horse’ in attempting to present demographics as a solution to our woes rather than a the merely analytic tool which it is. Wayne Eaton (online comment)

Misogyny

Dear Editor, Wow! Lisa Gorton’s poem ‘’On the Characterisation of Male Poets’Mothers’ is beautifully written, it is also a devastating analysis of the culturally embedded nature of misogyny (ABR, May 2020). How painful to think of all those mothers receiving slap after slap in the face from their anxious, needy, entitled, selfish, infuriatingly talented sons – wanting to support, but flayed for doing so! Tom Gutteridge (online comment) A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

5

Our partners

Australian Book Review is assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council for the Arts, its arts funding and advisory body. ABR is supported by the Victorian Government through Creative Victoria; the Queensland Government through Arts Queensland; the Western Australian Government through the Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries; and the South Australian Government through Arts South Australia. We also acknowledge the generous support of our university partner Monash University; and we are grateful for the support of the Copyright Agency Cultural Fund; the City of Melbourne; and Arnold Bloch Leibler.

6 A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

Parnassian ($100,000 or more) Ian Dickson

Acmeist ($75,000 to $99,999) Olympian ($50,000 to $74,999) Morag Fraser AM Colin Golvan AM QC Ellen Koshland Maria Myers AC

Augustan ($25,000 to $49,999)

Anita Apsitis and Graham Anderson Dr Steve and Mrs TJ Christie Peter Corrigan AM (1941–2016) Peter and Mary-Ruth McLennan Pauline Menz Kim Williams AM Anonymous (1)

Imagist ($15,000 to $24,999)

Emeritus Professor David Carment AM Professor Glyn Davis AC and Professor Margaret Gardner AC Lady Potter AC CMRI Ruth and Ralph Renard Anonymous (1)

Vorticist ($10,000 to $14,999)

Peter Allan Helen Brack Professor Ian Donaldson and Dr Grazia Gunn Emeritus Professor Anne Edwards AO Peter McMullin Allan Murray-Jones Professor Colin and Ms Carol Nettelbeck Margaret Plant Estate of Dorothy Porter David Poulton Peter Rose and Christopher Menz John Scully Emeritus Professor Andrew Taylor AM Anonymous (1)

Futurist ($5,000 to $9,999)

Geoffrey Applegate OBE and Sue Glenton Gillian Appleton Hon. Justice Kevin Bell AM and Tricia Byrnes Dr Neal Blewett AC Dr Bernadette Brennan John Button (1932–2008) Des Cowley Professor The Hon. Gareth Evans AC QC Helen Garner Cathrine Harboe-Ree Professor Margaret Harris The Hon. Peter Heerey AM QC Dr Alastair Jackson AM Neil Kaplan CBE QC and Su Lesser Dr Susan Lever Susan Nathan Professor John Rickard Ilana Snyder and Ray Snyder AM

ABR Patrons

Noel Turnbull Mary Vallentine AO Susan Varga and Anne Coombs Bret Walker SC Ruth Wisniak OAM and Dr John Miller AO Anonymous (1)

Modernist ($2,500 to $4,999)

Jan Aitken Helen Angus Kate Baillieu John Bryson AM Professor Jan Carter AM Donna Curran and Patrick McCaughey Reuben Goldsworthy Dr Joan Grant Tom Griffiths Mary Hoban Elisabeth Holdsworth Claudia Hyles Dr Kerry James Dr Barbara Kamler Professor John Langmore AM Geoffrey Lehmann and Gail Pearson Dr Stephen McNamara Don Meadows Stephen Newton AO Jillian Pappas Dr Trish Richardson and Mr Andy Lloyd James Dr Jennifer Strauss AM Lisa Turner Dr Barbara Wall Nicola Wass Jacki Weaver AO Emeritus Professor Elizabeth Webby AM Anonymous (5)

Romantic ($1,000 to $2,499)

Nicole Abadee and Rob Macfarlan Samuel Allen and Beejay Silcox Professor Frank Bongiorno AM John H. Bowring John Bugg Jean Dunn Professor Helen Ennis Johanna Featherstone Professor Sheila Fitzpatrick Professor Paul Giles Professor Russell Goulbourne Professor Nick Haslam Dr Michael Henry AM Professor Grace Karskens Linsay and John Knight Pamela McLure Muriel Mathers Rod Morrison Dr Brenda Niall AO Angela Nordlinger Diana and Helen O’Neil Mark Powell Professor David Rolph Dr Della Rowley (in memory of Hazel Rowley, 1951–2011)

Professor Lynette Russell AM Robert Sessions AM Michael Shmith Professor Janna Thompson Ursula Whiteside Lyn Williams AM Kyle Wilson Anonymous (5)

Symbolist ($500 to $999)

Professor Michael Adams Lyle Allan Douglas Batten Judith Bishop Professor Nicholas Brown Donata Carrazza Blanche Clarke Robyn Dalton Allan Driver Dr Paul Genoni Dr Peter Goldsworthy AM Dilan Gunawardana Emeritus Professor Dennis Haskell AM Dr Max Holleran Dr Barbara Keys Dr Brian McFarlane OAM Marshall McGuire and Ben Opie Peter Mares Felicity St John Moore Patricia Nethery Professor Brigitta Olubas Professor Anne Pender J.W. de B. Persse Emeritus Professor Wilfrid Prest Dr Jan Richardson Libby Robin Stephen Robinson Emeritus Professor Susan Sheridan and Professor Susan Magarey AM Emeritus Professor Ian Tyrrell Emeritus Professor James Walter Professor Jen Webb Professor Rita Wilson Dr Diana and Mr John Wyndham Anonymous (3)

Realist ($250 to $499)

Damian and Sandra Abrahams Jean Bloomfield Rosyln Follett Andrew Freeman FACS Dr Anna Goldsworthy Associate Professor Michael Halliwell Margaret Robson Kett John McDonald Michael Macgeorge Dr Lyndon Megarrity Penelope Nelson Lesley Perkins Anthony Ritchard Margaret Smith Anonymous (2)

The Australian Government has approved ABR as a Deductible Gift Recipient (DGR). All donations of $2 or more are tax deductible. To discuss becoming an ABR Patron or donating to ABR, contact us by email: development@australianbookreview.com.au or by phone: (03) 9699 8822. In recognition of our Patrons’ generosity ABR records regular donations cumulatively. (ABR Patrons listing as at 25 May 2020)

Politics

Failures of judgement

Turnbull remains unsure exactly what role Scott Morrison and his supporters played in the events of that week, but he was relieved that it was Morrison and not Dutton who became Memoirs of an unlikely Liberal leader prime minister. Turnbull’s take on Morrison is the only pubJudith Brett lished close-up view we have so far of the man who is now our leader. Turnbull regards him as a purely political animal, with few policy convictions, and widely distrusted by his colleagues. He also believes that Morrison’s compulsive leaking as treasurer derailed the government’s policy options, such as on the GST and negative gearing. There are detailed chapters on his government’s major domesA Bigger Picture tic and foreign policy achievements. He is especially proud of the by Malcolm Turnbull same-sex marriage legislation’s victory over the Coalition’s right Hardie Grant Books wing. Many of the staunchest advocates of ‘traditional’ marriage, $55 hb, 704 pp he notes, were the keenest practitioners of traditional adultery, alcolm Turnbull looks us straight in the eye from the a comment he repeats when discussing the ban on sexual relations cover of this handsome book, with just a hint of a between ministers and their staff, which he introduced after the smile. He looks calm, healthy, and confident; if there affair between Barnaby Joyce and his erstwhile media adviser are scars from his loss of the prime ministership in August 2018, became public. He had already had to speak to several ministers they don’t show. The book’s voice is the engaging one we heard about this kind of thing, he writes, leaving us to wonder who. Turnbull’s singular failure was not achieving an energy policy when Turnbull challenged Tony Abbott in July 2015 and promised a style of leadership that respected people’s intelligence. He that took seriously Australia’s responsibility to lower its emistakes us from his childhood in a very unhappy marriage, through sions. Turnbull’s support for Kevin Rudd’s Emissions Trading scheme was the catalyst school and university, his asfor his losing the Liberal tonishing successes in media, Party leadership to Tony business, and the law, his entry Abbott in 2009, and he into politics as the member for trod softly on climate Wentworth, and ends with his when he became leader exit from parliament. a second time. After the It is a Sydney story, full of first loss he went into a the Sydney identities Turnblack depression, the first bull worked with as he made time this ebullient, gifted his name and fortune: Kerry man had risked serious Packer, of course, but a host of mental illness. While he others, and the politicians, like considered leaving poliNeville Wran and Bob Carr, tics for good, he stayed, who were his friends. Like the and he believes that he young Paul Keating, Turnbull emerged from the darksat at the feet of Jack Lang. The ness a better, stronger, stories of his successes, friendless self-absorbed perships, and enmities before son. It was this better he entered politics are lively person, determined to conand well told, but they have a sult widely, whom many of rehearsed feel, the jagged edges Scott Morrison with Malcolm Turnbull before the 2016 Budget us found so frustrating. worn away. The book’s energy (Andrew Meares/SMH, from the book under review) Why wouldn’t he ‘do a is in his three years as prime Gough’, crash through minister (2015–18) which or crash in a confrontation with the climate deniers? This book occupy more than half the book. The brutal twists and turns of the week in August 2018 when helps us understand. The prime minister Turnbull is most like is Whitlam, both Peter Dutton challenged Turnbull make for compelling reading, not least because Turnbull is so frank in his character assessments brilliant, ambitious Sydney lawyers with big visions and big egos. of the key players. He was amazed that anyone, including Dut- But where Whitlam was able to ride a hunger for change in ton, could seriously think he was a viable candidate for leader. Australia, the times did not suit Turnbull. He was not a partisan He believed that Greg Hunt was motivated solely by his desire warrior in a parliament that had become polarised, at least since to be foreign minister in Dutton’s cabinet. He was hurt by what John Howard and toxically so under Abbott; and he was not he saw as betrayal by Mathias Cormann, whom he had come to sufficiently tribal for the Liberal right, which believed he was a Labor Trojan horse. trust and had thought was his friend.

M

8 A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

There have always been rumours that Turnbull tried to join the Labor Party. However true these are, he concluded, rightly, that he belonged in the party committed to individualism and free enterprise, not the party of collectivism and the unions. He hoped he would be able to steer the Liberals back to the centre, closer to its liberal foundations, and as prime minister he worked hard to build consensus. He eschewed ‘captain’s calls’ and restored proper processes of cabinet government after the Abbott debacle. He didn’t hate Labor, and he was widely criticised by his side for not running a negative campaign in 2016. Nor did he heed the many warnings from his colleagues about whom not to trust, which was pretty well everyone in the senior team. If he had, he writes, ‘I would not have been able to work with any of them’, nor achieve anything.

Why wouldn’t he ‘do a Gough’, crash through or crash in a confrontation with the climate deniers? This book helps us understand Paul Keating said of Turnbull, ‘brilliant, utterly fearless and no judgement’. This book gives plenty of evidence to confirm all three qualities. The achievements of his early adulthood are astonishing: courting the great and powerful; achieving extraordinary successes, like defeating the British government in the Spycatcher case; and making serious money. Other reviewers have criticised some of these accounts as a little self-serving, and no doubt they are. Most people are unreliable narrators of their own lives. It was the lack of judgement that most interested me when I read the book, and Turnbull’s buoyant, unrealistic optimism. When he first became prime minister, Turnbull kept telling us that this was the most exciting time to be an Australian, to be alive even, full of challenges and opportunities. Really, I thought, compared with the booming Australia of the 1950s, or the first days of the Whitlam government? And what about the sense of dread so many of us feel about the heating planet and the degraded natural world our grandchildren seem set to inherit? As leader, there were two spectacular failures of judgement. The first was the Godwin Grech affair of June 2009 when, as leader of the Opposition, Turnbull accused Prime Minister Rudd of giving special treatment to a mate on the basis of emails that Grech, a public servant, leaked to him. He liked and trusted Grech, but the emails turned out to be fake and he was hugely embarrassed. The second was his decision to take the country to a double dissolution election in July 2016. It was a foolish decision, which I can only put down to an over-optimistic reading of his government’s electoral chances. A normal election could have been held as soon as August, and the trigger was unconvincing – to pass the Building and Construction Industry bills. Turnbull thought the election would deliver a more workable Senate. Instead, the Coalition barely scraped home, and he destroyed a massive amount of political capital. A Bigger Picture gives us clues to the origins of this lack of judgement in its first chapter on Turnbull’s childhood. His parents, Coral and Bruce, were ill-suited, an ambitious, intellectual woman and a good-looking, knockabout guy. They married a year after Malcolm was born, but the marriage didn’t last. When

Malcolm was about eight, his mother left for New Zealand with another man. He was sent to boarding school, where he was desperately unhappy, and Bruce brought him up. The story Bruce told his young son was that Coral had gone to study and that she loved him more than anything else on earth. Maybe she did, but she had left him, and this truth only slowly became apparent to him as ‘her absence crept up on me like a slow, cold chill around the heart’. By sheltering him from the truth, Bruce was protecting his son’s self-esteem, but perhaps he also weakened his reality-testing capacities, leaving him vulnerable to unrealistic optimism and misplaced trust. In one important life matter, though, Turnbull’s judgement was impeccable. He wed his wife, Lucy, forty years ago this March, and together they have built a loving, supportive marriage of equals and raised two children. He told Leigh Sales that he had always had ‘a stronger sense of Lucy and me than I do of me’. Turnbull lost the leadership twice because of his belief that climate change was real. In office he was unable to act effectively on this belief. Seeming to promise so much, he turned out to be a disappointment, as leaders so often do. For all the hopes we project onto them, our political leaders are only people, trying to do their best with the circumstances and the colleagues fate gives them. I finished this book with a great deal of sympathy for Turnbull. He failed to defeat the climate deniers in his party, but at least he tried. g Judith Brett’s most recent book is From Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage: How Australia got compulsory voting (2019).

Missed an issue?

Purchase new and back issues of the print magazine via our website for just $12.95 ‒ postage free! Alternatively, you can get digital access from just $10 a month (auto-renewal). Annual digital subscriptions for individuals are $60. Terms and conditions apply, for more information, visit our website:

www.australianbookreview.com.au A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

9

Politics

Democracy’s parasite

of popular sovereignty. The challenge for Keane is shape-shifting despotism. Every despot is different, from foghorn extremes to subtle local variants. Is despotism our future? Keane includes a wide array of countries in the category, from Glyn Davis Turkey and Iran to Brunei and Singapore, with particular attention paid to China and Russia. He argues that despotism is not an old style of government revived but a ‘form of extractive power with no historical precedent’. There is no single definition offered for this protean concept. Instead, Keane builds, chapter by chapter, a set of despotism’s The New Despotism characteristics, exploring each angle in detail, complete with local by John Keane terms and topical jokes to show how general trends play out in specific regimes. Harvard University Press (Footprint) Despotism, argues Keane, makes a virtue of avoiding the $69.99 hb, 320 pp divisions and conflict of democracy. Despots emphasise national ohn Keane is Australia’s leading scholar of democracy, with character, the unity possible under a single ruler. They offer ultrawork that demonstrates an impressive command of global modern states, keen to be seen as more efficient than democracies, sources. Keane’s most widely cited book, The Life and Death more responsive to popular opinion. Rulers present themselves of Democracy (2009), included new research on the origins as voices of the people, ruling in their name. of public assemblies in India many centuries before the familBehind this façade is the apparatus of surveillance, tight control iar democracy of Greek city-states. Keane located the origins of of social media, and the ability to make critics disappear. Despots democracy in non-European traditions, in part by tracing the use public-opinion surveys to understand popular moods, and tame linguistic origins of the concept. media to lead public discussion. Violence is always the implicit threat, but the aim is stability. What despots want, above all, is voluntary servitude. This many achieve, ruling through seduction rather than terror. Across the globe, Keane reports the willingness of citizens to surrender political involvement for a quiet life. A clever despot ‘lures subjects into subjection’ so eventually ‘the slave licenses the master’. In particular, argues Keane, the middle class proves fickle about demo-cratic principles. It can be bought with good services, cash payments, and being left alone. Older political theory expected a prosperous middle class to demand representation. Yet any assumed link between a bourgeoisie, capitalism, and democracy is daily disproved around the world. Early in The New Despotism, Keane suggests that he might follow the example of Machiavelli’s The Prince and describe the inner dynamics of power outside democracy. This proves hard to deliver, since despotic regimes are rarely open or accessible to independPresident Donald Trump shakes hands with Chairman of the Workers’ Party of Korea ent research. So there is less Machiavelli than Kim Jong Un in 2019 when the two leaders met at the Korean Demilitarized Zone. Montesquieu or Tocqueville, intelligent observers (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead via Wikimedia Commons) trying to make sense of the gap between form This engagement with language and evidence is deployed and substance in every despotic state. once more in The New Despotism, an ambitious study of the Despots embrace many of the outward symbols of accountnon-democratic world. Despotism as a term fell out of use in the able and legitimate democracy. They use elections to test the twentieth century, replaced by concern about totalitarian states. public mood and identify potential opponents. Such contests are Keane seeks to revitalise the concept, not as a mirror image of rarely free or fair. Despots proclaim the rule of law, yet everyone democracy but, worryingly, as something that can grow out of understands that courts can be manipulated by corruption or by democracy. As his many examples show, this century has seen the state using the law to close down its enemies. Despots promote the closing down of accountability and free elections until states social media to ensure lively public discussions yet just out of sight retain the formal institutions of democracy but not the reality wait the censors, those cyber units that influence opinion, release

J

10 A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

Politics disinformation, discredit other voices, and silence unwanted conversations. There are armies of Winston Smiths from 1984, trained to create a simulacrum of free speech. Hence the claim of novelty. These new despots are not dinosaur authoritarian regimes, the lumbering dictatorships of North Korea or Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe. They are instead flexible regimes led by ‘learning despots’, determined to develop long-term regimes, using ‘whip-smart ruling methods’. Despots point to failed democratic states to say there is no obvious alternative. Should neighbouring democracies prove robust, they can be disrupted by the same cyber units developed for domestic control. The New Despotism is important because it brings an acute understanding of democracy to focus on its potential fate. The first chapter in particular is a tour de force about the overly optimistic reading of the future after 1989, when democracy briefly became the dominant form of government around the world, only to slide away in many states.

Violence is always the implicit threat, but the aim is stability. What despots want, above all, is voluntary servitude Keane argues that this was not just an unsuccessful transition to democracy. It was instead a reaction to the perceived failure of democracy, the inefficiencies associated with party competition, the cynicism of people who see around them high levels of inequality, poor leadership, the hollowing of social life, dark money in elections, cuts to public services and repressive responses to terrorism. At some point, the promise of strong government and order through despotism becomes attractive. And so a book on despotism completes its circuit, starting and finishing with democracy. If nations committed to popular rule do not address internal deficiencies, they risk populism and illiberal movements. Despotism is not the opposite of democracy, but a parasite that resides within, waiting for its opportunity. Will Keane succeed in reviving the concept of despotism? Though boundaries blur and a single definition remains elusive, he makes a strong case in The New Despotism for the urgent need to understand this global trend. Keane offers not just a lively argument with numerous examples, and a rich assembly of sources through detailed endnotes, but also a writing style that commands attention. Democracy faces ‘desolation row’ but is marked by ‘braided tempos and multiple rhythms’. The patron–client relations that run through despotic societies mean that ‘every soul is implicated in nested circles of soiled solidarity’. The analysis embraces a poetics of power, offering cumulatively a description as dark as Machiavelli on principalities. Here is no historical portrait but our times made stark. Democracy may once again become rare in a world dominated by despotic empires with no commitment to the rule of law. As John Keane, scholar of democracy, asks in his final sentence: is despotism our future? It is a disturbing but pressing question from a major new study. g Glyn Davis is CEO of the Paul Ramsay Foundation and Distinguished Professor of Political Science at the Australian National University.

Myths and realities

Two Labor prime ministers from gold towns Frank Bongiorno

Becoming John Curtin and James Scullin: The making of the modern Labor Party by Liam Byrne

J

Melbourne University Press $34.99 pb, 194 pp

ohn Curtin and James Scullin occupy very different places in whatever collective memory Australians have of their prime ministers. On the occasions that rankings of prime ministers have been published, Curtin invariably appears at or near the top. When researchers at Monash University in 2010 produced such a ranking based on a survey of historians and political scientists, Curtin led the pack, with Scullin rated above only Joseph Cook, Arthur Fadden, and Billy McMahon. Admittedly, this ranking was produced before anyone had ever thought of awarding an Australian knighthood to Prince Philip, but the point is clear enough: Curtin rates and Scullin does not. Liam Byrne’s pairing of the two men in this book is therefore in some ways a peculiar one. Scullin and Curtin are not usually considered in the same frame. The touching Peter Corlett statue in Canberra is of Curtin and Ben Chifley, a truly famous wartime partnership, rivalled in Australian politics only by the more fractious one of Bob Hawke and Paul Keating four decades later. But Byrne reminds us that in Parliament House during the war, Scullin occupied the office between those of Curtin and Chifley. Byrne’s pairing of Scullin and Curtin draws attention to the entangled lives of these men in the early Australian Labor Party. Both were products of Irish Catholic working-class families from provincial Victoria. More specifically, each came from the Ballarat district, Scullin from Trawalla, Curtin from Creswick. That in itself tells the reader something important. In a highly urbanised country, the country town has been a nursery of political and cultural vitality, and Victorian gold towns especially so. But gold towns were also places to leave. Both men would head for Melbourne, Scullin some way behind Curtin. Byrne’s subtitle is The making of the modern Labor Party, yet this is something of a misnomer. It is a peculiarly Victorian political milieu that he evokes, and he does that skilfully enough. But Byrne does have a point. While the Labor Party in Victoria was something of a Cinderella among Labor branches until the 1980s, it has exercised a remarkable influence well beyond its borders. It is not just that it generated these two Labor prime ministers. It also produced New Zealand’s first, in Michael Savage in 1935, while the fate of the Victorian branch of the party would be decisive in shaping Labor’s national fortunes – mainly for the worse – in the seemingly interminable Menzies era. For Byrne, Scullin was a ‘moderate’ and Curtin a ‘socialist’. He treats these as two quite distinct traditions, even allowing A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

11

that they shared some common ground. I am less certain how meaningful this distinction is for the Victorian labour movement of the early twentieth century. It is true that Curtin’s rhetoric was more aggressive, and he was more willing, as a young man, to contemplate the use of the general strike for political purposes, such as in stopping the outbreak of war. His understanding of the

professional benefits and personal associations may well tell us more about the reasons for Scullin’s close relationship with the AWU than any particular ideological commitment to moderation. It was the AWU that paid Scullin as a country organiser, and the AWU that came to the rescue with the editorship of a labour daily in Ballarat when Scullin lost his seat at the 1913 election. What is most striking is not the cigarette paper’s difference between the ideologies of two men who regarded themselves as socialists, but the ideas and aspirations they had in common. Both were tribally Labor. Both saw parliament, and not the union movement, as the main pathway to the realisation of their ideals. Both fully understood that Rome wasn’t built in a day, even if Curtin was more inclined to put aside that insight in the interests of his next speech or newspaper article.

At Parliament House during the war, Scullin occupied the office between those of Curtin and Chifley

Prime Minister James Scullin in Canberra, 1931 (National Library of Australia, nla.obj-161732766)

causes of such conflict bears more than a passing resemblance to the ideas of Vladimir Lenin, not least, as Byrne shows, because it had similar roots in the radical liberal ideas of British author J.A. Hobson. But by the end of World War I, Scullin’s understanding was hardly very different from Curtin’s. Where Curtin cut his political teeth in the Victorian Socialist Party under the mentorship of British socialist Tom Mann and English migrant Frank Anstey, Scullin was closely associated with the powerful Australian Workers’ Union, the successor to the old shearers’ union, a bastion of political caution and pragmatic wheeling and dealing. Byrne does show that Scullin shared some of that organisation’s preoccupation with causes such as land reform. But the AWU was also Scullin’s patron. He first entered the federal parliament as the representative of a rural electorate, and two of his sisters were married to AWU officials. These 12 A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

Both have been recalled as tragic figures. High office helped ruin the health of each, even if Scullin came to be treated as a failure for his Depression-era prime ministership (1929–32) and Curtin as a hero for inspiring wartime leadership (1941–45). It may well be time to alter this balance. Scullin’s task in the Depression was impossible in a way that Curtin’s job of wartime leadership was not. The economic policy on which Scullin’s government eventually settled in 1931, while not quite what it wanted, rightly received the praise of John Maynard Keynes. A conservative government might not have been able to achieve that without considerable civil disobedience. Meanwhile, the Curtin myth remains so potent and alluring that one sometimes has the suspicion of being taken for a ride. How much was it the strain of war, and how much was it too many cigarettes, too much stodgy food, too much grog, and the temperament of a deep worrier that drove him to an early grave? Byrne is a lively writer. If Australian labour history has on occasion been a bit dour, it’s not a fault we find here. Of an early communist speaking at a union conference in 1921, he writes: ‘[ Jock] Garden replied that he could not outline how to overthrow the system in the five minutes allotted. The conference, therefore, politely granted him an extension to ten.’ Socialism, as Byrne points out, is once again on the political agenda in a way that would have seemed inconceivable in the aftermath of 1989. That has happened for similar reasons to the upsurge of the early decades of the twentieth century: it makes increasing sense as a lens through which to view both the world as it is and the world as it might be. Scullin and Curtin pursued socialism through the Labor Party. Byrne, while critical of the present Labor Party’s lack of vision, is more optimistic than me about its capacity to respond to the challenges and opportunities of our times. g Frank Bongiorno is Professor of History at the Australian National University. His first book was The People’s Party: Victorian Labor and the radical tradition 1875–1914. He lives in Scullin in the Australian Capital Territory.

We need dividends to live on but we want to leave Category planet a better for our kids

That’s understandable. You know you can have a positive impact by urging the companies you invest in to improve their business practices

It looks pretty good!

They engage with big companies on social and environmental issues and then ask them to do better by putting resolutions to them with the support of shareholders like us Great!

Check out what these guys do and sign up if you’re

But we’re concerned about the ethics of some of the companies we own shares in

The ACCR is a not-for-profit research organisation that holds shares in many listed Australian companies. We engage with companies on issues such as climate, human rights and labour rights. Depending on the outcome of our engagement, we may coordinate a shareholder resolution.

Let’s sign up!

accr.org.au/support-resolutions

Meanwhile at ACCR and across Australia... Expert research...

... discussion with companies...

ACCR Shareholder Resolution

Here’s the resolution!

We ask our fellow shareholders to come together in support of this resolution and we urge our company to do better.

... and affected community

Oh wow! The ACCR resolution got a lot of investor LT SU RE CR C A

The board is going to improve!

Great! I’m glad!

Me too!

That’s really good news.

They got the message!

Politics

The Prahran grocer

An influential if obscure Victorian leader Benjamin T. Jones

Democratic Adventurer: Graham Berry and the making of Australian politics by Sean Scalmer

A

Monash University Publishing $39.95 hb, 349 pp

ustralians have a healthy appetite for political memoirs and biographies at a federal level. It is not only the scandal-ridden set of recent prime ministers with juicy details of political assassinations that sparks interest. The popularity of David Headon’s First Eight Project has demonstrated that the lives of Australia’s first national leaders are still a source of deep fascination. Even Earle Page, who only held the top job for nineteen days, is being rediscovered, thanks to Stephen Wilks’s 2017 PhD thesis from ANU. That Barnaby Joyce, one of Page’s distant successors as party leader,could secure a book contract speaks more to popular interest in federal leaders than to the quality of his prose. The ongoing public fascination with federal actors on the political stage sits in stark contrast to the relative indifference to their colonial predecessors. This is surprising, as the scandals and drama that filled the columns of colonial newspapers were every bit as sensational as the revelations that excite our modern Twitterati. The subject of Sean Scalmer’s rich biography is a case in point. The career of Graham Berry (1822–1904) was as exciting as they come. It is a tale replete with sex scandals, class antagonism, democratic struggle, constitutional crisis, and threats of revolution. And yet, despite being a three-time Victorian premier (1875, 1877–79, 1880–81) and a leading colonial politician for four decades, at his death the newspapers commented on the underwhelming crowd and felt obliged to remind readers whom they were mourning. Much could be written on why Australians neglect their colonial past. In the early twentieth century, it was perhaps the ongoing embarrassment of the ‘convict stain’ that was better left in the past. In the early twenty-first century, it is often the uncomfortable truth of Indigenous dispossession that is avoided. The result has been that 1901 forms a precise and tenacious line of forgetting. The career of Alfred Deakin falls ever so slightly on the ‘right’ side of this line. Despite being the nation’s second prime minister, he was the first of Headon’s First Eight to be honoured when the project launched in 2018. The year before, he was the subject of Judith Brett’s award-winning biography. All the more remarkable then that Berry, one of Deakin’s most important political mentors, has received little scholarly treatment since Geoffrey Bartlett’s PhD thesis in 1964 (also from ANU). Scalmer has rescued not only the man but his key ideas and intellectual legacy. The protectionist movement that profoundly shaped the early 14 A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

Commonwealth was not an invention of Deakin and Barton, nor even of the influential proprietor of The Age, David Syme. If it has a single intellectual progenitor, it is probably Berry, though Scalmer rightly notes that these ideas were circulating even before his conversion. The Eureka Stockade of 1854 is often seen as a novelty of sorts in Australian history. Like Canada’s Rebellions of 1837–38, it can too easily be dismissed as an uncharacteristic tantrum from an otherwise well-behaved child of the British Empire. But the democratic convictions that led to that fatal shootout, and the popular demand that (white) Victorian men were entitled to a gun, a vote, and land, was not extinguished with the granting of responsible government. Berry, who was one of the jurors to acquit the Eureka rebels in a highly popular miscarriage of justice, was a key figure in moving the democratic campaign from violent to intellectual combat. The battle lines would no longer be drawn at makeshift forts on the goldfields but inside that eminently British institution, the Victorian parliament.

Berry, one of Deakin’s most important political mentors, has received little scholarly treatment Scalmer skilfully unpacks the way Berry responded to early electoral defeats and took charge of his political narrative. When his blueblood opponents used his supposedly Dickensian origins as a slur, he returned fire to expose their snobbery. The ‘Prahran grocer’ would use – indeed exaggerate – his humble beginnings to frame himself as a genuine tribune of the people. Trained initially as a London draper and running a successful family business, he was working class but no Oliver Twist when he set sail for Melbourne. At the heart of this book is the struggle between the popular lower house and the conservative upper house. It was an intellectual contest for the ‘true’ meaning of the unwritten constitution seen, in many variations, around the British Empire. After little Nova Scotia distinguished itself as the first British colony to receive responsible government in 1848, the limits of democracy were negotiated all over the British world. One of Scalmer’s real achievements in this book is demonstrating the ferocity of the democratic struggle in Victoria and the way Berry utilised the first organised political party to push the pendulum in the people’s favour. This is no hagiography. Scalmer is quick to point out just how narrow Berry’s conception of ‘the people’ was. First Nations Peoples and the Chinese were certainly not part of his democratic adventure. While open to expanding the Victorian polis to women, this was not high on his political agenda either. Scalmer maintains a disciplined focus on Berry’s political life and presents this engrossing story in fewer than 300 pages, excluding notes. He resists the urge to draw on the rich reservoir of personal correspondences in the Berry Papers and to paint a broader picture of colonial society, a tendency that has resulted in a some Brobdingnagian colonial biographies (Don Baker’s colossal treatise on John Dunmore Lang comes to mind). Scalmer states

plainly that the menu card Berry perused in the members’ dining room is of no interest to him. For this reason, the book maintains a sharpness throughout, and Berry’s heavy influence on Victorian and Australian democracy becomes all the more clear. Democratic Adventurer is a valuable contribution to our knowledge of Berry and deftly demonstrates how the democratic battles of a nineteenth-century colony shaped a twentieth-century nation. There are moments of rhetorical excess. Was Berry the most gifted and controversial colonial politician, as the author claims? In Victoria perhaps. Charles ‘Slippery Charlie’ Cowper, in New South Wales, was just as skilful politically and just as effective in establishing democratic norms. Lang, the irascible preacher, politician, republican, and occasional jailbird, was just as radical

and controversial. If Scalmer’s admiration for his subject occasionally shines through, it is not to the detriment of this excellent book. This is a historian at the top of his game. Democratic Adventurer will be required reading for those who study colonial Australia, but its clear focus, accessible style, and the excitement of the tale will attract a popular audience also. g Benjamin T. Jones is a lecturer in history at Central Queensland University and a Foundation Fellow of the Australian Studies Institute. His most recent books are This Time: Australia’s republican past and future (Redback, 2018) and History in a Post-Truth World: Theory and praxis (Routledge, 2020). ❖

Politics

‘The laws are not silent’

How war can distort ideas of right and wrong Kieran Pender

Law in War: Freedom and restriction in Australia during the Great War by Catherine Bond

A

NewSouth $34.99 pb, 246 pp

s with many authors, Covid-19 forced Catherine Bond to cancel the launch event for her new book. But unlike most authors’ work, the contemporary relevance of Bond’s latest book has been considerably heightened by the ongoing pandemic. Indeed, in the midst of this crisis it is hard to imagine a historical text timelier than Law in War: Freedom and restriction in Australia during the Great War. A century later, lessons from that era are still instructive today. Covid-19 has had a dramatic impact on people’s lives. At the time of writing, Australians cannot leave their homes except in narrowly defined circumstances. Domestic and international borders have been sealed. The government is effectively underwriting the economy. In a society governed by law, these changes have been brought about by hastily drafted legislation and regulation. The extent of the power now lawfully wielded by Australia’s federal and state executives is unparalleled in living memory. Yet there is some precedent. On two other occasions in this federation’s 120-year history, external events – world wars – have precipitated fundamental changes to the compact between citizen and state. As Bond writes in Law in War, a lively study of legal developments on the home front between 1914 and 1918, World War I saw a ‘revolution of a government against its people, motivated by a higher cause: victory in war’. A century later, Bond’s analysis of the tools of that revolution is insightful as our laws are again

co-opted, this time to defeat Covid-19. Prior to Law in War, this subject was largely overlooked. Historian Charles Bean, commissioned in the 1920s to oversee the Official History of Australia in the War, had at first agreed to include a substantial section on domestic legal manoeuvrings. At the urging of federal solicitor-general Sir Robert Garran, Bean backflipped, noting that it was ‘doubtful if such a chapter is called for’. Garran, the man who wrote most of Australia’s wartime laws, thereby effectively ensured that there would be no sustained reflection on their impact. By providing the first ‘holistic examination of Australia’s First World War legal regime’, Bond aims to fill that ‘gap’. She does so thematically across eight chapters, each focused on one or a handful of characters. This methodology was deliberate: ‘All too often,’ the academic writes, ‘I have found law to be divorced from people.’ Bond argues that this is a collective failing of the academy: ‘law is all about people. Individuals write the law. Individuals interpret the law. Individuals are held accountable by the law.’ She thus recounts the tales of an eclectic range of individuals – from Prime Minister Billy Hughes to suffragette Adela Pankhurst, from drug-makers George Nicholas and Harry Woolf Shmith to Indigenous serviceman Douglas Grant – to tell a broader story.

The extent of the power now lawfully wielded by Australia’s federal and state executives is unparalleled in living memory Bond ranges widely across different areas of law. She considers a statute that cancelled the intellectual property rights of German companies (spurring a local pharmaceutical industry), and another that limited the ability of ‘enemy subject’ employees to contest their termination, empowering widespread employment discrimination. Bond notes that a federal police force was created overnight by regulation after Queensland cops refused to arrest protesters who had egged Hughes. She also discusses the discriminatory legal barriers to Australians of non-European complexion enlisting, which prevented many Indigenous and Asian Australians from serving on the frontline. A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

15

Bond is at her best when discussing the draconian limitations on civil and personal liberties enacted during World War I. The story of Franz Wallach is harrowing: a Frankfurt-born merchant, Wallach had lived in Australia for more than two decades by 1914, and had renounced his German citizenship. Despite no evidence of disloyalty, Prime Minister Hughes’s personal dislike of Wallach and his metal-trading company saw the trader interned for four years. Wallach successfully contested his internment in the Victorian Supreme Court, but the federal government promptly issued a revised regulation. Wallach was rearrested before he could depart the courthouse. As one Labor MP quipped during legislative debate over detention powers, ‘the war seems already to have distorted our ideas of right and wrong’. The government’s approach to political dissent had a similarly dictatorial hue. Bond outlines the various legal tussles of activist Pankhurst and her peers, which ultimately concluded unsuccessfully in the High Court. Despite a powerful dissent from Justice Henry Higgins – ‘constitutional limitations are not suspended; we have to decide in accordance with the Constitution’ – a majority upheld the validity of Pankhurst’s conviction for protesting. Bond, though not blind to the unusual imperatives of war, suggests that the judicial branch failed to maintain adequate scrutiny of the executive. She quotes Justice Edmund Barton in another case: ‘We have nothing to say as to the wisdom or otherwise of any regulation: that is a matter for the Legislature.’ This approach, says Bond, is ‘disappointing’. With limited legislative scrutiny and an executive making law by regulation, ‘the courts were one of the few avenues available to the Australian people for a rigorous

review of these wartime laws’. The High Court declined that role. Law in War is written with scholarly rigour, complete with abundant primary and secondary sources, while remaining accessible for a generalist audience; this is no law textbook. Bond crisply explains legal concepts and is adroit at providing necessary context along the way (‘it is helpful to pause here to note’), rather than all at once. Despite the book’s often technical subject matter, she writes with flair and wit: ‘Resources and reputation enabled Franz Wallach to fight the law. Of course, the law won.’ Any possible critiques are minor: Bond is overly fond of internal cross-references (‘as noted earlier’), and chunky legislative extracts sometimes feel unnecessary. A lengthier book (Law in War is barely 200 pages long) might have considered the wartime legal experience elsewhere – was Australia typical or exceptional? But these shortcomings hardly detract. Bond’s latest book is engaging, insightful, and important. Above all, Law in War offers a timely reminder that in situations of great upheaval, the law is not always a reliable guarantor of justice. During World War I, Australia’s laws served as tools of ‘discrimination, oppression, censorship, and deprivation of property, liberty and basic human rights’. Too often, lawyers and the judiciary were complicit. With Australians facing another era-defining challenge, we should learn from our mistakes. Law in War provides a helpful guide. As a British jurist once remarked, ‘amidst the clash of arms’, or, perhaps, personal protective equipment, ‘the laws are not silent’. g Kieran Pender is an Australian writer and lawyer.

Dawn Solo

First light beside the Murray in Mildura, Which like a drift of mist pervades The eucalypt arcades, A pale caesura Dividing night and day. Two, three clear notes To usher in the dawn are heard From a pied butcherbird, A phrase that floats So slowly through the silence-thickened air, Those notes, like globules labouring Through honey, almost cling And linger there. Or is it that the notes themselves prolong The time time takes, to make it stand, Morning both summoned and Called back by song.

Stephen Edgar Stephen Edgar’s new and selected poems, The Strangest Place, is due out later this year from Black Pepper. 16 A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

Literary Studies

Unsolicited smut

A nation of prudes and wowsers James Ley

The Trials of Portnoy: How Penguin brought down Australia’s censorship system by Patrick Mullins

O

Scribe $35 pb, 329 pp

kay, I’ll tell you what’s wrong with this country. For a start, we have this profoundly stupid and deeply irritating myth that we’re all irreverent freedom-loving larrikins and easygoing egalitarians, when it is painfully obvious that we have long been a nation of prudes and wowsers, that our collective psyche has been warped by what Patrick Mullins describes, with his characteristic lucidity, as ‘a fear of contaminating international influences’, and that we are not just an insular, conservative, and deeply conformist society, but for some unaccountable reason we take pride in our ignorance and parochialism. And let’s not neglect the fact that we are cringingly deferential and enamoured of hierarchy. Oh yes, it’s all master– slave dialectics and daddy issues around here. Why the hell else would we keep electing entitled, smirking, condescending autocrats? In fact, there are few things your average patriotic Australian likes better than the authoritative clamour of some deadeyed, bull-necked crypto-fascist bashing on the bathroom door and demanding to know what we’re reading in there. Which, for most of the twentieth century, was not much. We banned Balzac, for fuck’s sake. We banned Lawrence and Huxley and Nabokov. We banned Hemingway, Baldwin, Vidal, Salinger, Donleavy, Burroughs, Miller, and McCarthy. We banned Ulysses, then unbanned it, then realised our mistake and banned it again. We prosecuted Max Harris for publishing a poet who didn’t even exist. For a while there, the list of banned books was banned. But then what happens if I read one of them by accident, Dr Spielvogel? Mullins has all the receipts. For years it was ‘assumed incontrovertibly by common law that obscene writings do deprave and corrupt morals, by causing dirty-mindedness, by creating or pandering to a taste for the obscene’. Who stands a chance against such impeccable circular reasoning? No wonder the country is a neurotic mess. No wonder we can’t even get philistinism right. When the attitude of our guardians of public morality for most of the last century was ‘I have no idea what this is or what it might mean, and I have no intention of finding out, but I don’t like it’, declaring ‘I know what I like’ represented a significant advance. Saying ‘I know it when I see it’ qualified you as an intellectual. Of course, the whole wacky censorship regime was justified on the grounds that it was upholding ‘community standards’, disregarding the obvious point that if the community had any standards there would be no need to uphold them. What standards? Artie Fadden’s trade minister, Eric Harrison, thought he knew

what they were, but only because he copied out all the rude bits of Ulysses and mailed them to some church groups. Apparently, they weren’t impressed. He should have referred himself to the vice squad – I mean, what kind of creep sends unsolicited smut to little old ladies? This is all in Mullins’s book, if you’re interested, which you should be, because believe me the same clueless creeps are still in charge. Mullins wrote a biography of Billy McMahon, so he understands better than most that the dominant genre of Australian political life is farce. The Trials of Portnoy is about a rare instance of sanity prevailing, though of course a regime of unrelieved idiocy doesn’t just collapse of its own accord. It needs to be brought down. A few cheeky student publications were never going to achieve anything. No, it took a novel of perverted genius, a novel backed by a major publisher, a novel about a compulsive onanist that’s so funny that anything it touches instantly becomes ridiculous. Fight farce with farce was the basic idea. And hoo-boy did it work. It was like that Monty Python sketch about a joke that’s so funny it kills people. The book immediately sells 100,000 copies and they’re debating whether or not it meets ‘community standards’. A communist bookstore over in Western Australia sold so many copies they were able to renovate with the profits! It’s brilliant when you think about it. I don’t know, Dr Spielvogel. For some reason, I find debates about ‘literary merit’ incredibly funny. And I find the thought of lawyers debating literary merit before bewigged judges even funnier. Imagine writing a book that’s basically an extended psychiatrist-couch gag about a guy who can’t Philip Roth, 1968 stop pulling his putz (Photo by Bob Peterson/The LIFE Images and it leads to a string Collection via Getty Images/Getty Images) of court cases trying to establish if it’s ‘obscene’. If! Imagine them all in their robes, scratching their beards, trying to work out if a novel about a neurotic jerkoff has ‘depraving’ effect. Well, they all read it. They should know! Picture a procession of the nation’s finest literary minds summoned as expert witnesses. Such experts! James McAuley, Vincent Buckley, Patrick White, Fay Zwicky, Dorothy Hewett – all taking the stand to attest to the literary merits of a novel about a guy who whacks off into his sister’s brassiere. But what about the bit where he sticks his schlong in the raw liver? Oh, that bit’s especially meritorious, m’lud. Some academic called the book enriching. I mean, this is Alexander Portnoy we’re talking about here. If he’s enriching, where’s a guy supposed to go for a little depravity? A qualified psychologist testified that the novel had ‘the truth of a tone poem or landscape’. When that happens, you know you’ve won. It’s a funny thing, Dr Spielvogel, I can’t quite explain it, but reading Mullins’s book actually made me feel a little better. g James Ley is a Melbourne essayist and literary critic. A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0

17

Literary Studies

‘The thing I mostly am’ The many treks of Robyn Davidson Sophie Cunningham

On Robyn Davidson: Writers on Writers by Richard Cooke

T

Black Inc. $17.99 hb, 96 pp

he women that Robyn Davidson had a powerful effect on, Richard Cooke tells us, include author Anna Krien, adventurer Esther Nunn, and his wife. ‘I watched as the power of this book and its author, their energy and weight, worked an entrainment across cultures and generations,’ writes Cooke. In some ways his essay charts his struggle with that power. How not to fall into the trap that others who have tackled Davidson have fallen into? ‘I lagged decades of writers and pilgrims, interlopers and fans. Reading interviews to try to chicane through the questions already asked was pointless. They most often sought answers about the same thing – her first book, now published forty years ago.’ That book, of course, was Tracks. Everyone wanted a piece of Davidson before, during, and after its publication, but the more she insisted on her desire to be alone the more people wanted to get close to her. There was a deep, slightly pervy fascination with a twenty-six-year-old woman undergoing a 2,500-kilometre journey from Alice Springs to the coast of Western Australia, with three camels and a dog, in the late 1970s. The people who made versions of that journey not irregularly, Indigenous Australians, were treated with contempt. A white bloke would not have garnered the same attention. In Tracks, Davidson talks at length about the racism and sexism that fuelled social relations in central Australia, and Cooke draws on this to make interesting observations on the ways in which Davidson’s book changed the way we understood our First Peoples and their lands (though even as recently as 1996 the difference between Davidson’s first book, Tracks, and her second, Nomads, was reviewed thus by Rosalind Sharpe in the Independent: ‘Australia, with its empty, hygienic spaces, sprinkled with people who understand English, was unimaginably different from India.’) Cooke also does a good job of conveying Davidson’s extraordinary charisma – informed, to be sure, by a real intelligence, grit, determination, and all-consuming rage – a charisma that catapulted her across a continent, into the public’s consciousness. I appreciated his insight into one of the sources of that charisma: the desert itself. ‘By venturing into the desert, Robyn Davidson was also entering a literary landscape.’ As I read Cooke on Davidson, however, I was aware of a distance between the critic and his subject, one that was not in the other Writers On Writers books I have read. In On Patrick White, Christos Tsiolkas discusses the impact of Manoly Lascaris, 18 A U S T R A L I A N B O O K R E V I E W J U N E – J U LY 2 0 2 0