Frank Bongiorno Critic of the Month

Frances Wilson Wolfram Eilenberger

Maggie Nolan Gail Jones’s new novel

Ben Gook The swindle of fascism

Scott Stephens Kevin Hart

The spectre of tribalism

Dennis

Altman on Israel, AIDS and identity politics

*INC GST

GOLD MEDAL Readers’ Favorite 2023 International Book Awards

“Exits has profoundly impacted the literary world.”

— Midwest Book Review

“Pollock's poetry is brilliant.”

— Kristiana Reed, editor in chief of Free Verse Revolution

“Dedicated to the beauty and frailty of life, Exits exemplifies the musicality of language.”

— Foreword Clarion Reviews

“Full of wit, insight and provocative imagery, Exits is a masterful collection. The formal poems are the best. Some are sonnets as artful as any by Shakespeare.”

— IndieReader, ★★★★★

EXITSPOETRY.NET

Advances

Peter Porter Poetry Prize

Dan Hogan has won the twentieth Peter Porter Poetry Prize. Dan, who was chosen from an international field of 1,066 entries, received the prize (worth $6,000) at an online ceremony on 23 January, where the other four shortlisted poets – Judith Nangala Crispin, Natalie Damjanovich-Napoleon, Meredi Ortega, and Dženana Vucik – also read their poems. Our judges – Lachlan Brown, Dan Disney, Felicity Plunkett – had this to say about the winning poem, ‘Workarounds’, in their official report, which is available online (as is a podcast of all five poets reading their poems):

‘Workarounds’ remains a stunning critique of the so-called 4th Industrial Revolution, in a lexicon that could (almost) be the gibberish of a pre-ChatGPT machine attempting to replicate human thought … but not quite. Amid apparent non sequiturs, the heroically outlandish expressiveness, the absurd sleights and puns, there are moments of challenge to those alert to the fact that this poem may be investing in social critique rather than mere post-LangPo fun. ‘Property the essential,’ the text infinitively urges, ‘the cement world is everything a unit of / productivity could want’, Hogan hefting their loaded syntax into defamiliarising lines that are hilarious and sombre, strikingly original, and braided with possibility. In an era of emerging global precarities, this intervention refuses to move quietly into the ranks of alienated labor, instead ironising the ‘refranchise[d] exquisite / doldrums’. Readers are indeed up for some kind of ‘existential kneecapping’. In a maximalist language that is taut, experimental, and has something urgent to say about the Zeitgeist, ‘Workarounds’ worries zanily, darkly, and scrupulously.

Dan Hogan, on learning of their win, told Advances:

I was surprised to bits to learn my poem had won the 2024 Peter Porter Poetry Prize. Deepest thanks to Australian Book Review, the judges, and those behind the prize. Recognising poetic daring, the Porter Prize is an important prize due to its international scope, and so it is an immense honour to join the prize’s rich lineage of poems and poets.

Vale David Hansen (1958–2024)

ABR was greatly saddened to learn of the sudden death on 13 January of art historian David Hansen, aged sixty-five. David held many positions – senior curator, gallery director, and, latterly, associate professor at the Australian National

University. He wrote for ABR on several occasions: his articles were reliably stylish and individual. In 2007, he was commended in the inaugural Calibre Essay Prize. Three years later, his essay ‘Seeing Truganini’ was awarded the Calibre Prize and also the Alfred Deakin Prize for an Essay Advancing Public Debate in the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards.

2024 Blak & Bright

The 2024 Blak & Bright First Nations literary festival, will take place in Melbourne from March 13 to 17. The festival’s fourth instalment features eighty First Nations artists across thirty events. Guests include Kim Scott, Melissa Lucashenko, and ABR contributors Tony Birch, Kirli Saunders, and Julie Janson. This year’s theme, ‘Blak Futures Now’, is a ‘call to action’, with Festival Director Jane Harrison inviting people to ‘experience the future of the millennia-old tradition of storytelling’.

Critic of the Month

Among ABR’s most popular features are our five Q&As: Open Page, Critic of the Month, Poet of the Month, Publisher of the Month – and the newcomer, Backstage, where we invite a leading arts professional to nominate the best performance they have ever seen, to proffer advice to young artists, and to reveal what they really think of audiences and arts critics!

Anna Goldsworthy – celebrated pianist, memoirist, festival director, essayist, and much more – is our Backstager this month. Asked to nominate the single biggest thing governments could do for artists, she nominates ‘a universal basic income’. Hear, hear!

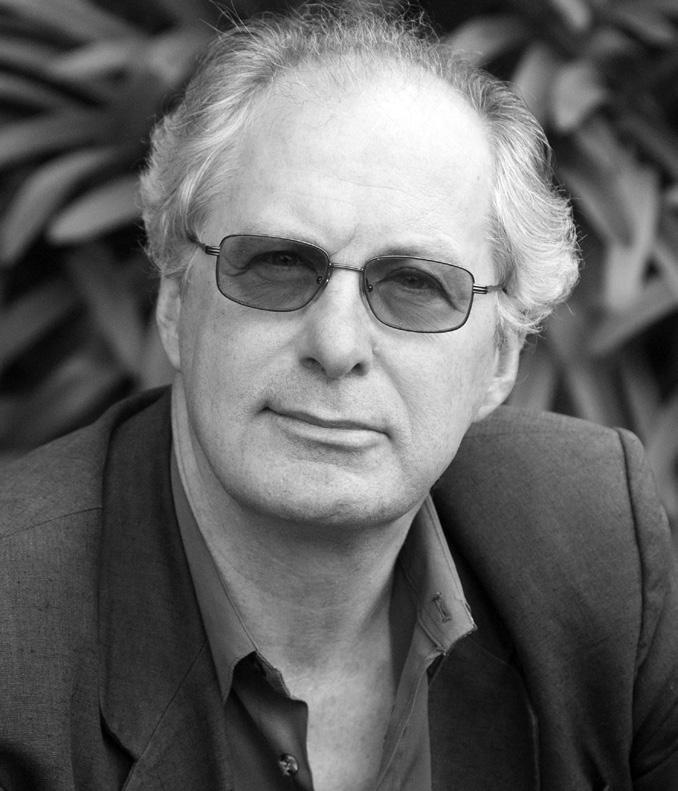

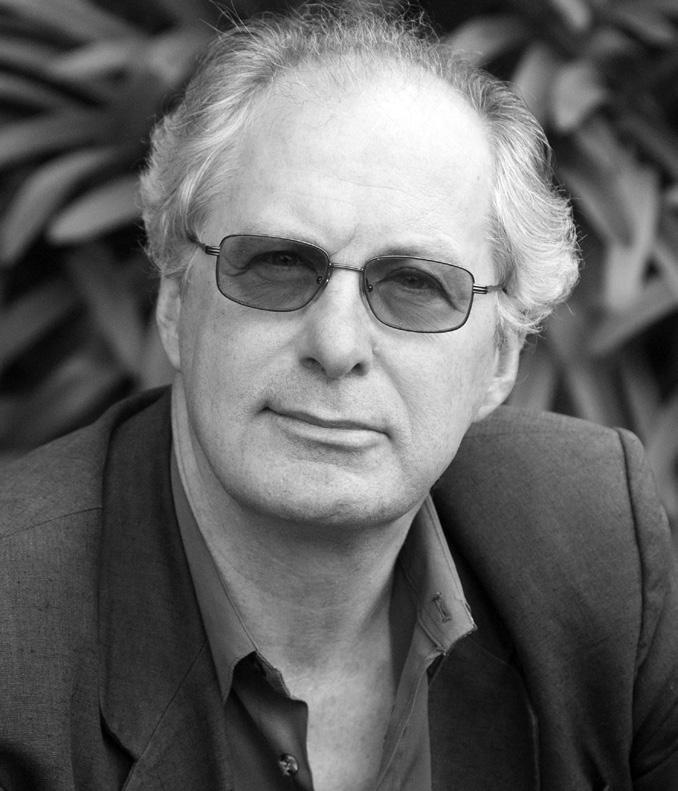

Frank Bongiorno – historian, academic, author – is our Critic of the Month. Peter Rose interviews him this month on the ABR Podcast, the first in a series of conversations with some of ABR’s senior critics.

Tours galore

Once again in the first week of March, ABR is off to Adelaide, where the magazine was founded in 1961. We have a full contingent for our third annual Adelaide tour.

Meanwhile, interest in our Vienna tour is strong, but there are still some places left. Christopher Menz – former gallery director and curator, and ABR’s Development Consultant – will lead the Vienna tour. Full details are available on the Academy Travel website. g

The Climate Crisis and Other Animals

Richard Twine MARCH 2024

Australian Book Review

March 2024, no. 462

First series 1961–74 | Second series (1978 onwards, from no. 1)

Registered by Australia Post | Printed by Doran Printing

ISSN 0155-2864

ABR is published eleven times a year by Australian Book Review Inc., which is an association incorporated in Victoria, registered no. A0037102Z.

Phone: (03) 9699 8822

Twitter: @AustBookReview

Facebook: @AustralianBookReview

Instagram: @AustralianBookReview

Postal address: Studio 2, 207 City Road, Southbank, Vic. 3006

This is a Creative Spaces studio. Creative Spaces is a program of Arts Melbourne at the City of Melbourne. www.australianbookreview.com.au

Peter Rose | Editor and CEO editor@australianbookreview.com.au

Amy Baillieu | Deputy Editor abr@australianbookreview.com.au

Georgina Arnott | Assistant Editor assistant@australianbookreview.com.au

Rosemary Blackney | Business Manager business@australianbookreview.com.au

Christopher Menz | Development Consultant development@australianbookreview.com.au

Poetry Editor

John Hawke (with assistance from Anders Villani)

Chair Sarah Holland-Batt

Deputy Chair Billy Griffiths

Treasurer Peter McLennan

Board Members Graham Anderson, Declan Fry, Johanna Leggatt, Lynette Russell, Robert Sessions, Beejay Silcox, Katie Stevenson, Geordie Williamson

ABR Laureates

David Malouf (2014), Robyn Archer (2016), Sheila Fitzpatrick (2023)

ABR Rising Stars

Alex Tighe (2019), Sarah Walker (2019), Declan Fry (2020), Anders Villani (2021), Mindy Gill (2021)

Monash University Interns

Gordon Leong, Anastasia Richmond-Miller

Volunteers

Alan Haig, John Scully

Contributors The ❖ symbol next to a contributor’s name denotes that it is their first appearance in the magazine.

Acknowledgment of Country

Australian Book Review acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the Kulin Nation as Traditional Owners of the land on which it is situated in Southbank, Victoria, and pays respect to the Elders, past and present. ABR writers similarly acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands on which they live.

Subscriptions

One year (print + online): $100 | One year (online only): $80

Subscription rates above are for individuals in Australia. All prices include GST. More information about subscription rates, including international, concession, and institutional rates is available: www.australianbookreview.com.au

Email: business@australianbookreview.com.au

Phone: (03) 9699 8822

Cover Design Amy Baillieu

Letters to the Editor We welcome succinct letters and online comments. Letters and online comments are subject to editing. The letters and online comments published by Australian Book Review are the opinions of the named contributor and not those of ABR. Correspondents must provide contact details: letters@australianbookreview.com.au

Advertising Amy Baillieu – abr@australianbookreview.com.au Media Kit available from our website.

Environment ABR is printed by Doran Printing, an FSC® certified printer (C005519). Doran Printing uses clean energy provided by Hydro Tasmania. All inks are soy-based, and all paper waste is recycled to make new paper products.

Image credits and information

Front cover: Dennis Altman, Gay Mardi Gras, 1981 (photograph by William Yang)

Page 37: SLNSW 822153 No 56 Linda Lampe Franklin, sister of Stella Miles Franklin c.1868-1952 (State Library of New South Wales via Wikimedia Commons)

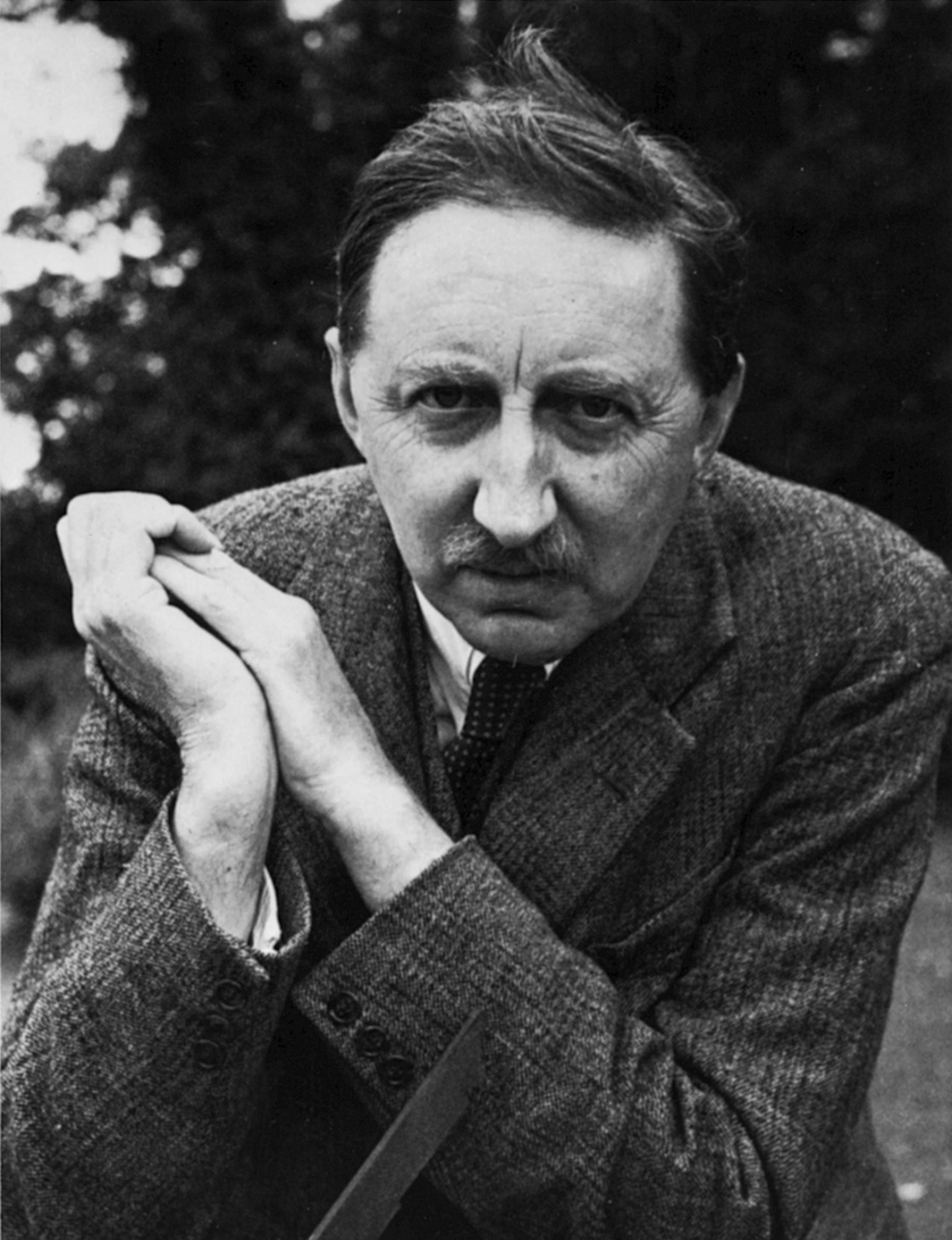

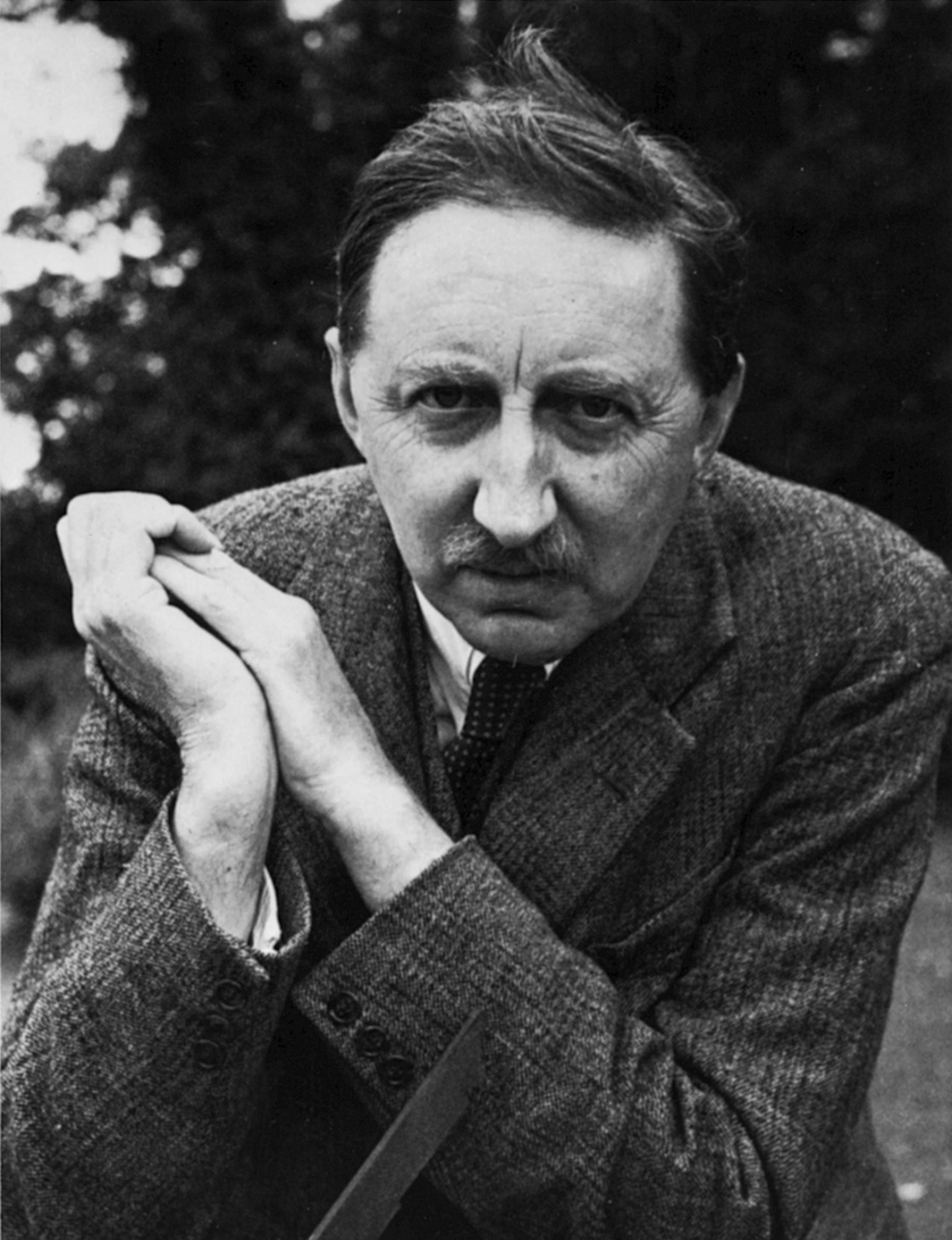

Page 59: E.M. Forster (1879-1970) (GRANGER - Historical Picture Archive/Alamy)

2 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024

ABR March 2024

LETTERS

POLITICS COMMENTARY

CLASSICS

PHILOSOPHY EUROPE

IRELAND POEMS

LITERARY STUDIES

FICTION INTERVIEWS

POETRY

GAMING

NATURAL HISTORY

HISTORY

SOCIETY MEMOIR

FILM

ABR ARTS

FROM THE ARCHIVE

Kevin Foster et al.

Ben Gook

Stephanie Collins

Patrick Mullins

Dennis Altman

Nathan Hollier

Alastair Blanshard

Frances Wilson

Clinton Fernandes

Ronan McDonald

Autumn Royal

Peter Rose

Sarah Day

Sue Kossew

Tim Mehigan

Scott Stephens

Maggie Nolan

James Bradley

Suzanne Falkiner

Giselle Au-Nhien Nguyen

Andrew Leigh

Frank Bongiorno

Anna Goldsworthy

David McCooey

Anthony Lynch

Chris Flynn

Ashley Hay

Miles Pattenden

Seumas Spark

Bridget Vincent

Susan Sheridan

Richard Leathem

Joshua Black

Tim Byrne

Stephanie Trigg

Late Fascism by Alberto Toscano

The Penitent State by Paul Muldoon

The Menzies Watershed edited by Zachary Gorman Menzies versus Evatt by Anne Henderson

The Spectre of Tribalism

Pramoedya Ananta Toer and the Buru Quartet

Homer and his Iliad by Robin Lane Fox

The Iliad by Homer, translated by Emily Wilson

The Visionaries by Wolfram Eilenberger, translated by Shaun Whiteside

Eurowhiteness by Hans Kundnani

Making Empire by Jane Ohlmeyer

‘A house—I will not paint’ ‘Portfolio’ and ‘Syllabus’ ‘Arrow’

Shooting Blanks at the Anzac Legend by Donna Coates

The Bloomsbury Handbook to J.M. Coetzee edited by Andrew van der Vlies and Lucie Valerie Graham Lands of Likeness by Kevin Hart

One Another by Gail Jones

The Great Undoing by Sharlene Allsopp

My Brilliant Sister by Amy Brown Politica by Yumna Kassab

Open Page

Critic of the Month Backstage

Ghosts of Paradise by Stephen Edgar

Mishearing by David Musgrave

AfterLife by Kathryn Lomer

Critical Hits edited by Carmen Maria Machado and J. Robert Lennon

What the Trees See by Dave Witty

Emperor of Rome by Mary Beard

British Internment and the Internment of Britons edited by Gilly Carr and Rachel Pistol

Kin by Marina Kamenev

Slipstream by Catherine Cole

Film Music by Kathryn Kalinak

Nemesis

The Inheritance

Wild Surmise by Dorothy Porter

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024 3

8 11 14 15 18 33 23 24 26 27 29 43 45 30 31 42 38 39 40 41 44 49 63 46 47 50 51 52 54 55 56 58 60 62 64

Our partners

Australian Book Review is supported by the South Australian Government through Arts South Australia.

We also acknowledge the generous support of our university partner, Monash University; and we are grateful for the support of the Copyright Agency Cultural Fund; Good Business Foundation (an initiative of Peter McMullin AM), Australian Communities Foundation, AustLit, the City of Melbourne; and Arnold Bloch Leibler.

Arts South Australia

4 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024

Updated

2024 ABR Elizabeth Jolley Short Story Prize

The Australian Book Review Elizabeth Jolley Short Story Prize is one of the world’s major prizes for an original short story, with $12,500 in prizes.

The Jolley Prize closes on 22 April 2024. It will be judged by Patrick Flanery, Melinda Harvey, and Susan Midalia

The Jolley Prize honours the work of the Australian writer Elizabeth Jolley. It is open to anyone in the world who is writing in English. Entries should be original single-authored works of short fiction of between 2,000 and 5,000 words.

Full details and online entry are available on our website: www.australianbookreview.com.au

• Second prize:

•

ABR warmly acknowledges the generous support of ABR Patron Ian Dickson AM.

Maria Takolander

Gregory Day & Carrie Tiffany

Sue Hurley

Michelle Michau-Crawford

Jennifer Down 2015 Rob Magnuson Smith 2016 Josephine Rowe 2017 Eliza Robertson 2018 Madelaine Lucas 2019 Sonja Dechian 2020 Mykaela Saunders 2021 Camilla Chaudhary 2022 Tracy Ellis 2023 Rowan Heath 2024 ?

winners Updated Full-page Jolley Prize for March 2024 issue.indd 1 20/02/2024 11:54:51 AM

First prize: $6,000

$4,000

Third prize: $2,500

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

previous

ABR Patrons

The Australian Government has approved ABR as a Deductible Gift Recipient (DGR). All donations of $2 or more are tax deductible. To discuss becoming an ABR Patron or donating to ABR, contact us by email: development@australianbookreview.com.au or by phone: (03) 9699 8822. In recognition of our Patrons’ continuing generosity, ABR records multiple donations cumulatively. (ABR Patrons listing as at 21 February 2024)

Parnassian ($100,000 or more)

Ian Dickson AM

Acmeist ($75,000 to $99,999)

Blake Beckett Fund

Morag Fraser AM

Maria Myers AC

Olympian ($50,000 to $74,999)

Anita Apsitis and Graham Anderson

Colin Golvan AM KC

Augustan ($25,000 to $49,999)

In memory of Kate Boyce, 1935–2020

Professor Glyn Davis AC and Professor Margaret Gardner AC

Neil Kaplan CBE KC and Su Lesser

Pauline Menz (d. 2022)

Lady Potter AC CMRI

Ruth and Ralph Renard

Mary-Ruth Sindrey and Peter McLennan

Kim Williams AM

Anonymous (2)

Imagist ($15,000 to $24,999)

Australian Communities Foundation (Koshland Innovation Fund)

Emeritus Professor David Carment AM

Emeritus Professor Margaret Plant

Peter Rose and Christopher Menz

John Scully

Emeritus Professor Andrew Taylor AM

Vorticist ($10,000 to $14,999)

Peter Allan

Geoffrey Applegate OBE (d. 2021) and Sue Glenton

Professor The Hon. Kevin Bell AM KC and Tricia Byrnes

Dr Neal Blewett AC

Helen Brack

Emeritus Professor Anne Edwards AO

Good Business Foundation (an initiative of Peter McMullin AM)

Dr Alastair Jackson AM

Steve Morton

Allan Murray-Jones

Susan Nathan

Professor Colin Nettelbeck (d. 2022) and Ms Carol Nettelbeck

David Poulton

Emeritus Professor Ilana Snyder and Dr Ray Snyder AM

Susan Varga

Futurist ($5,000 to $9,999)

Gillian Appleton

Professor Frank Bongiorno AM

Des Cowley

Professor The Hon. Gareth Evans AC KC

Helen Garner

Cathrine Harboe-Ree AM

Professor Margaret Harris

Linsay and John Knight

Dr Susan Lever OAM

Don Meadows

Jillian Pappas

Judith Pini (honouring Agnes Helen Pini, 1939–2016)

Professor John Rickard

Robert Sessions AM

Noel Turnbull

Mary Vallentine AO

Bret Walker AO SC

Nicola Wass

Lyn Williams AM

Ruth Wisniak OAM and Dr John Miller AO

Anonymous (3)

Modernist ($2,500 to $4,999)

Professor Dennis Altman AM

Helen Angus

Professor Cassandra Atherton

Australian Communities Foundation (JRA Support Fund)

Judith Bishop and Petr Kuzmin

Professor Jan Carter AM

Donna Curran and Patrick McCaughey

Emeritus Professor Helen Ennis

Professor Sheila Fitzpatrick

Roslyn Follett

Professor Paul Giles

Jock Given

Dr Joan Grant

Tom Griffiths

Michael Henry AM

Mary Hoban

Claudia Hyles OAM

Dr Barbara Kamler

Professor Marilyn Lake AO

Professor John Langmore AM

Kimberly Kushman McCarthy and Julian McCarthy

Pamela McLure

Dr Stephen McNamara

Emeritus Professor Peter McPhee AM

Rod Morrison

Stephen Newton AO

Angela Nordlinger

Mark Powell

Emeritus Professor Roger Rees

John Richards

Dr Trish Richardson (in memory of Andy Lloyd James, 1944–2022)

Emerita Professor Susan Sheridan and Emerita Professor Susan Magarey AM

Dr Jennifer Strauss AM

Professor Janna Thompson (d. 2022)

Lisa Turner

Dr Barbara Wall

Emeritus Professor James Walter

Emeritus Professor Elizabeth Webby AM (d. 2023)

Anonymous (3)

Romantic ($1,000 to $2,499)

Damian and Sandra Abrahams

Lyle Allan

Paul Anderson

Australian Communities Foundation

Gary and Judith Berson

Professor Kate Burridge

Joel Deane

Jason Drewe

Allan Driver

Jean Dunn

Elly Fink

Stuart Flavell

Steve Gome

Anne Grindrod

Associate Professor Michael Halliwell

Robyn Hewitt

Greg Hocking AM

Professor Sarah Holland-Batt

Anthony Kane

Professor Mark Kenny

Alison Leslie

David Loggia

Professor Ronan McDonald

Hon. Chris Maxwell AC

Felicity St John Moore

Penelope Nelson

Patricia Nethery

Dr Brenda Niall AO

Jane Novak

Diana and Helen O’Neil

Barbara Paterson

Estate of Dorothy Porter

Professor John Poynter

Emeritus Professor Wilfrid Prest AM

Dr Ron Radford AM

Ann Marie Ritchie

Libby Robin

Stephen Robinson

Professor David Rolph

6 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024

Dr Della Rowley (in memory of Hazel Rowley, 1951–2011)

Professor Lynette Russell AM

Dr Francesca Jurate Sasnaitis

Michael Shmith

Jamie Simpson

Dr Diana M. Thomas

Professor David Throsby AO and Dr Robin Hughes AO

Dr Helen Tyzack

Ursula Whiteside

Kyle Wilson

Dr Diana and Mr John Wyndham

Anonymous (3)

Symbolist ($500 to $999)

Jeffry Babb

Douglas Batten

Professor Roger Benjamin

Jean Bloomfield

Dr Jill Burton

Brian Chatterton OAM

Professor Graeme Davison AO

Professor Caroline de Costa

Dilan Gunawardana

Dr Alison Inglis AM

Robyn Lansdowne

Michael Macgeorge

Emeritus Professor Michael Morley

Gillian Pauli

Anastasios Piperoglou

Professor Carroll Pursell and Professor Angela Woollacott

Alex Skovron

Professor Christina Twomey

Dr Gary Werskey

Anonymous (1)

Realist ($250 to $499)

Caroline Bailey

Antonio Di Dio

Kathryn Fagg AO

Barbara Hoad

Margaret Hollingdale

Margaret Robson Kett

Emeritus Professor Brian Nelson

Margaret Smith

Bequests and notified bequests

Gillian Appleton

Ian Dickson AM

John Button (1933–2008)

Peter Corrigan AM (1941–2016)

Dr Kerryn Goldsworthy

Kimberly Kushman McCarthy and Julian McCarthy

Peter Rose

Dr Francesca Jurate Sasnaitis

Denise Smith

Anonymous (3)

The ABR Podcast

Our weekly podcast includes interviews with ABR writers, major reviews, and creative writing. Here are some recent and coming episodes.

Stuart Kells

David McBride’s ethics

Kevin Foster

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024 7

Alan Joyce’s Qantas

stopping and thinking

2024

shortlisted

A maddening country

Deane

Cate Kennedy

The lives of ‘ordinary’ people Ebony Nilsson Frank Bongiorno Critics’ Corner with Peter Rose On

Scott Stephens Porter Prize

The

poems

Joel

‘Sleepers’

Letters

A cornerstone of our democracy

Dear Editor,

The world of Australian letters is incestuous. Friends routinely review and promote each other, sullying the critical waters and making it difficult for readers to know what is worth their money and time. Occasionally, this inbred criticism sparks a feud between warring literary clans (see Laura Elizabeth Woollett’s recent Sydney Review of Books piece on The First Time podcast). More often than not, it produces criticism that reads like vanilla ice-cream, sweet and soft.

Kevin Foster’s review of David McBride’s memoir, The Nature of Honour, is anything but vanilla (ABR, January–February 2024). Foster has an opinion of the author and his book, and he prosecutes that opinion. Speaking as a reader, it is informative. Speaking as a reviewer, it is measured. Speaking as an author, it is tough.

I’m not saying I agree or disagree with the Foster review, by the way. What I’m saying is that critical takes such as Foster’s review of McBride’s book are essential points of reference for informed, interrogative reading.

As for McBride, his social media temper tantrum over the review is juvenile. Don’t get me wrong, I understand why he’s upset about the review; I’ve received bad reviews, too. But here’s the thing: a free and fierce critical culture is, like corruption bodies and whistleblower protections, a cornerstone of our democracy.

The bottom line is that we can’t have a vigorous literary culture without vigorous critics. That’s why I’m glad that Kevin Foster wrote, and that ABR published, this review.

Joel Deane

As a book review, this is lacking. Even as an ad hominem attack, it is wanting. David McBride may not have been the whistleblower that the reviewer wanted, but he did identify that SOTG structures (and the entire Operation Slipper architecture after about 2009) were fundamentally morally compromised – like so many people I interviewed in my books about the Afghan war – and then he did something about it, which almost nobody did. This fact must at least be grudgingly acknowledged somewhere.

Ben Mckelvey

This reads more like a vindictive Facebook post than a scholarly review. ABR, in comments to Crikey, described Kevin Foster as a ‘fearless, cogent, informed reviewer’. In this case he is not. He is an aggressive, dismissive critic of David McBride, not an informed reviewer of a text.

Ronald Brown

I thought this was a good and insightful review of the book. Surely a reviewer has an obligation to try and understand the motives and intent of the author, especially in an autobiography? I believe Kevin Foster has done just that.

I found McBride’s book appallingly superficial, but for some strange reason I felt compelled to finish it. Having read Foster’s review, I believe that he has accurately and succinctly articulated what I was actually feeling.

Peter Kelly

It is ironic that David McBride and his supporters flock to criticise Kevin Foster’s review en masse. How dare it be suggested that McBride is self-interested, something the book appears to inadvertently reveal? This is a review of an autobiography, and so the subject’s opinion of himself as told in the book is highly relevant. The reviewer has indicated that the value in the book might be what McBride is inadvertently saying, rather than what he intends to say.

Mia Aghajanian

I can understand the reaction here, but it betrays a deliberate ignorance of the opening lines of the review. Don’t idolise your ‘heroes’ – they are all flawed. This was the message that David McBride was sending while broadcasting his own flaws. He was part of the culture that he found distasteful in relation to the values that he assumed as a privileged élitist. McBride discovered that error. We see exposed the class assumptions of McBride’s cultural milieu. He does not do it as a class warrior. For that he deserves the respect that the reviewer affords. He should not be hailed as (nor does he claim to be) another working-class hero, and for headlining that, the reviewer should be congratulated.

Warwick Fry

I thought this was going to be a review of David McBride’s book. However, it reads like a personal opinion of his career and character. I fail to see how this text can be classified as a book review.

Sharon Luhr

This is not a book review: it is a very unfair character assassination that seems personal. I am appalled that it was published.

Ken Ford

This is a character assassination and not a book review. Absolutely shameful.

Lyn Malone

That’s not a book review. That’s a shameful personal attack.

Melissa McLelland

The real heroes were the two journalists at the ABC who chose to reveal the truth and have paid a terrible price while choosing not to self-promote.

Carol Oakes

Can’t wait to read your autobiography, Kevin.

David McBride

8 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024

Kevin Foster replies:

A number of respondents to my review of David McBride’s The Nature of Honour have accused me of ‘character assassination’. Given that the subject of the review was an autobiography, I find this a little puzzling. McBride’s book concludes with his decision to leak classified documents to the media to expose what he believed was the endangerment of special forces troops in Afghanistan by ADF senior command. In what comes before this momentous decision, he takes the reader back through his life to explain who he is, how his values and beliefs have been shaped, how they affected the personal and professional choices he made, and so what it was that led him to do what he did. In the course of this, McBride inadvertently betrays patterns of thought and behaviour that reveal a man strikingly at odds with how he explicitly presents himself to the reader and how his supporters have portrayed him. In this context, failing to discuss McBride’s character would have been like reviewing Moby-Dick without discussing the sea.

Ben Mckelvey suggests that I have failed both as a reviewer and a hatchet-man, and that McBride deserves credit for leaking the material he did. Just to clarify, I reviewed what McBride chose to tell the reader about himself. The only hatchet on show here was of McBride’s own fashioning. I merely pointed out how he had laid about himself with it.

Mckelvey is wrong to claim that ‘almost nobody’ did something about the military crimes and moral failures in Afghanistan. Many serving and former special forces personnel spoke up about what they had seen and identified who was responsible, at considerable personal and professional cost. None of these people promoted him or herself as a champion of openness in the way that McBride has done.

As to his assertion that McBride was not the whistleblower that I wanted, Mckelvey implicitly raises the larger question of whether McBride’s motives mattered. Yes, they did. The ADF’s senior commanders ‘amplified’ the Rules of Engagement because they and their political masters were concerned about Afghan civilian casualties. McBride was resolutely opposed to these revisions. Convinced that they imperilled the men on the front lines, he laid out his objections in a twenty-four page, 101-paragraph memorandum to his superiors. When this was rebuffed, he handed classified files to the ABC, detailing what he thought were exemplary cases of the vexatious pursuit of special forces soldiers over civilian casualties, believing that their disclosure would force senior command to withdraw the amendments.

Careful what you wish for. In the same material, the ABC’s Dan Oakes and Sam Clark – the real heroes of this whole episode – found evidence that some of the special forces personnel McBride was working to shield from investigation had allegedly executed unarmed civilians and had then planted weapons and radios on the victims to cover their crimes. In the wake of these revelations, Australian Federal Police raided the ABC’s offices in Ultimo, and Oakes spent the next three years waiting to find out whether he would be prosecuted for doing his job. While Oakes sweated, McBride’s followers lauded him

as the man who had laid bare the dirty secrets of Australia’s war in Afghanistan. When the Commonwealth pursued him through the courts, his cheer squad canonised him as a martyr to free speech – a role he happily assumed, but did not deserve to play.

Sometimes the truth is as inconvenient as it is unpopular.

Israel and Gaza Dear Editor,

In order to explain to us why he does not subscribe to the expressions of horror and outrage at the Israeli state’s ethnic cleansing of Gaza and the West Bank, David Trigger recommends that we read his review of Michael Gawenda’s book My Life As a Jew (ABR, December 2023). Trigger approvingly cites Gawenda’s assertion that ‘accusing Israelis, and by extension Jews, of behaving like Nazis is now commonplace among parts of the far left’. This deft little phrase – ‘and by extension, Jews’ – is an inexcusable slur against the millions of people around the globe who have clearly made the crucial distinction between Jewish people and the racist Zionist state. Professor Trigger, by tacitly endorsing the words of Gawenda, should not be allowed to propagate this dangerous insinuation. It is exactly the kind of claim which is being deployed to silence critics of the Israeli regime. In the United States and elsewhere, a McCarthyite witch-hunt against these critics is now in full swing, driving respected senior academics from their posts. There is no question that similar techniques are being or will be employed here.

When Professor Trigger recites the mantra that historical comparisons drawn between Zionist supremacist ideology and Nazism is ‘commonplace among parts of the far left’, must we presume he is talking about people such as Albert Einstein, Hannah Arendt, Sydney Hook, and scores of other Jewish intellectuals who made that comparison as early as 1948, stating unequivocally that Menachem Begin and his Herut party (later to become Likud), of whom Netanyahu is the ideological heir, were ‘fascists’, ‘racists’, ‘criminals’, and ‘terrorists’?

Among the most disturbing political phenomena of our times is the emergence in the newly created state of Israel of the ‘Freedom Party’ (Tnuat Haherut), a political party closely akin in its organization, methods, political philosophy and social appeal to the Nazi and Fascist parties. It was formed out of the membership and following of the former Irgun Zvai Leumi, a terrorist, right-wing, chauvinist organization in Palestine … It is inconceivable that those who oppose fascism throughout the world, if correctly informed as to Mr Begin’s political record and perspectives, could add their names and support to the movement he represents.

(https://archive.org/detailsAlbertEinsteinLetter ToTheNewYorkTimes.December41948)

Trigger also fails to note that such comparisons appear to be more common among far-right Zionist ethno-nationalists, to the utter horror of the staff of the Auschwitz Museum. As reported in the Jerusalem Post, the Auschwitz Museum in Poland expressed their disgust at the following remarks made

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024 9 Letters

by Metula Council head David Azoulai: ‘The entire Gaza Strip should be emptied and leveled flat, just like in Auschwitz.’

Memory of victims of Auschwitz has, at times, been violated and instrumentalized in various extreme statements. Calling for acts that seem to transgress any civil, wartime, moral, and human laws, that may sound as a call for murder of the scale akin to Auschwitz, puts the whole honest world face-to-face with a madness that must be confronted and firmly rejected.

(https://www.jpost.com/israelhamas-war/article-778465)

Anthony Redmond

David Trigger replies:

This comment appears to be prompted by my disagreement in another forum over the wording of a particular statement, written by Anthony Redmond to garner signatures, condemning Israel as a racist state in light of its huge military response to the Hamas murders of civilians.

Despite this awkwardness in the context of ABR, the comment underscores Michael Gawenda’s point in his book My Life As a Jew (written before the present conflict in Gaza): that legitimate criticism of the current Israeli government too often bleeds into complete dismissal of the country’s moral right to exist.

Likening Israel to ‘fascism’ and ‘Nazism’ has become de rigueur in certain leftist quarters, but for most Jews and many non-Jews it is offensive and appears anti-Semitic precisely because it lacks factual support. The rant of an individual mayor of an Israeli town is cited as evidence; this is astoundingly naïve from a scholar in the social sciences. There are some extremists who have been brought into the current Israeli government in a multi-party system that relies on horse-trading and abject compromises and the sooner these politicians are gone the better. There are also serious issues regarding Palestinian rights that must be addressed. However, there is no significant widely supported Israeli ideology, movement, or policy that is equivalent to the Nazi attempt to exterminate Jews. Using accusations of ‘ethnic cleansing’ is sensationalist and a deliberate strategy of demonising the entirety of Israeli society.

Yes, there have been many views about the Zionist project among Jewish intellectuals. The enormous trauma of the Holocaust, alongside the long history of Jewish connections to the region, have produced a rich body of thought and diversity of opinion as to the complexities that inform modern Israel and its relationships with the global Jewish diaspora. The disagreements noted in a letter written in 1948, reflecting fierce ideological contestation within the Zionist movement, sit alongside a rich tapestry of continuing support for a viable Jewish homeland. Moreover, context matters. Menachem Begin, who is condemned in that letter, became the first Israeli prime minister to sign a historic peace treaty in 1978 with an Arab neighbour represented by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat.

Criticising aspects of current government policy or military strategy is part of normal political debate. However,

what is not all right is persistently calling Israel a Nazi state, and/or suggesting that the Jews who live there and defend their society are adherents to a ‘supremacist ideology’ and are like Nazis. Such vehement bluster is both hopelessly ignorant of history and devastating for Holocaust survivors, their children and grandchildren. It encourages an ugly and threatening rise in anti-Semitism across the world. The book I reviewed, My Life As a Jew, addresses such issues admirably.

A word much abused

Dear Editor,

Apropos of Frank Bongiorno’s review of Raimond Gaita’s book Justice and Hope, I think that what Gaita has in mind could better be described as honour, respect, and compassion, rather than love (ABR, January–February 2024). Love is a word that is much abused and misused, perhaps due to emotion, perhaps because it is misunderstood. The essence of love is placing the well-being of another above all else irrespective of the cost to oneself and without the slightest expectation of anything in return.

As for Socrates, Plato cites in extenso in his Symposium the long dialogue Socrates is reported to have had with the prophetess Diotima, in which she declares that ‘love is of immortality’. Like our involuntary body functions of heartbeat, breathing, etc., our involuntary mental functions of morality, altruism, and love are all cogs that keep the wheel of life turning.

Rodney Crisp

Arts Highlights of the Year

Thank you for a terrific round-up of arts highlights of 2023 (ABR, January–February 2024). It was marvellous to read about and relive some of the best.

Virginia Braden

A ripe peach

Dear Editor, Mounting a No case for the referendum was so easy (ABR, December 2023). It was the ripe peach that fell into Peter Dutton’s lap. For people engaged in promoting the Yes campaign, the level of ignorance about what constitutional change really meant must have been depressing.

In any case, I believe the expectation of what a Yes vote would have delivered, had it prevailed, was wildly optimistic. My husband and I both tried to change the vote of hard-line No voters – to no avail. Our arguments, forcefully put, fell on stony ground. In those moments, we saw the contented faces of white privilege looking back at us with pity.

Judith Masters

It is dismal and incomprehensible that Australia, one of the first countries in the world to give women the vote, despite its inherent misogyny, cannot recognise in its constitution, which hardly anyone has read or really cares about, the people who have lived in, loved, and protected this land for thousands of years.

Mary Billing

10 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024 Letters

Cult of the archaic

The swindle of fascist fulfilment

Ben Gook

ALate Fascism: Race, capitalism and the politics of crisis

by Alberto Toscano Verso

$36.99 pb, 212 pp

lready it has been a big year for fascists. On Australia Day, a handful of neo-Nazis from across Australia assembled in Sydney. Dwarfed by tens of thousands of protesters at Invasion Day rallies, the fascist stunt still generated the desired confrontation with the state and response from journalists drawn into the spectacle. Two weeks earlier, German investigative journalists published details of a late-2023 meeting in Potsdam, outside Berlin. At a neo-baroque lakeside hotel, an assortment of old money, political chancers, and neo-fascist intellectuals discussed a proposal for ‘remigration’. Among the retired dentists, bakery franchisers, and parliamentary staffers was Martin Sellner, the one-time, hot-young-Austrian-face of the European identitarian movement – a man so reactionary that even post-Brexit Britain denied him a visa.

In Remigration, a forthcoming book, Sellner fleshes out the masterplan of removing from German-speaking lands those citizens deemed unfit for the national project: ‘the remigration,’ as he puts it, ‘of culturally, economically, politically and religiously unassimilable foreigners’. This ugly euphemism expresses hostility to universal citizenship, perhaps the key continuity between classical and contemporary fascisms, as the Hungarian philosopher G.M. Tamas pointed out more than twenty years ago. Rather than referring to people’s return to the country from which they migrated, as in its sociological usage, this ‘remigration’ included a plan to build a ‘model state’ in northern Africa to receive up to two million deported people.

The reactionary conspiracy theories of racial replacement of white populations with immigrants are given their vicious response in remigration. This calls up a ‘border fascism’, the organising principle of much far-right thinking today. It offers violent fixes for a conjuncture in which mass migration from wars and economic exploitation has converged with the climate crisis.

As Alberto Toscano notes, expanding on the work of Brendan O’Connor, these fortified borders can be external (patrolled physical barriers) or internal (lines dividing the populace, such as gender and race). A ‘racial-civilisational crisis is spliced with scenarios of scarcity and collapse’, conjoining current crises of capitalism with fascism’s fixation on ‘epochal loss of privilege and purity’. In a word, Toscano defines fascism as ‘an anti-emancipatory politics of crisis’. A product and producer of crisis, it ‘strives violently to enshrine inequality by creating simulacra of equality for some – it is a politics and a culture of national-social

entrenchment, nourished by racism’.

Toscano outlines – in this book on the analogies, disanalogies, and non-analogies of today’s fascism and its historical variants –that the ‘lateness’ of fascism concerns its anachronism. The classic fascist fixes were bound to the capitalist crises of their time, as well as the era of mass manual labour, universal male conscription, and imperialist projects.

As Toscano points out, there is an irony in how fascists today are invested in the white, industrial, patriarchal, and social democratic modernity that followed the wartime defeat of fascist governments. Fascists now seek to revive and reimpose this era of late Fordist manufacture and apparent harmony in race and gender relations, taking it as a time of prosperity and pride, the glorious late coming of Order and Tradition.

It is a religion of death seeking to transcend the present and achieve a mythical rebirth

All ideologies are incoherent, but the hallmark of fascism is the coexistence of a deep investment in muscular, scientific modernism – all that gleaming steel and scientific racism back then, all those gleaming social media interfaces and protein powders now – alongside the deep myths, occult beliefs, and invented traditions of a putative past. Guy Debord called fascism ‘a cult of the archaic completely fitted out by modern technology’. This culture uses myths, symbols, and rituals to create a sense of authority and tradition that is beyond question.

Among those attracted to fascism, a feeling of impending – or actual – social catastrophe seems to be a catalyst or even, in many cases, a desire. Fascism feeds off a sense of disaster and the possibility of rebirth, hence the investment in violence and apocalyptic fantasies. It is a religion of death, seeking to transcend the present and achieve a mythical rebirth.

If fascism is an ideology of retribution and renewal, it appears as a possibility or contender at moments when the present is perceived as decadent, decayed, or degraded. Today, it circulates amid videos or podcasts railing against degenerate élites and outlining nefarious conspiracies, organised by a shotgun algorithmic marriage of wellness influencers and jilted young men. Fascism is not just a specialised and authoritarian state, but also a form of popular attachment and pleasure that relies on delegated and eroticised violence. It offers, as Ernst Bloch wrote, ‘the swindle of fulfillment’.

The impetus for Toscano’s book is the abandon with which fascism has been discussed in recent years, particularly since the election of Donald Trump in 2016. Much of this discussion –in liberal broadsheets and paperbacks – has taken the form of checklists or stage-by-stage historical accounts to assess whether we’re living in fascist times or not.

Toscano frustrates those looking for such easy answers. His book is a ‘metacommentary’ on historical and conceptual debates about fascism. He wants to displace the key analogies – Italy and Germany, 1920s and 1930s – to see how thinkers over the past century have responded to the varieties of fascism that emerged in different settings. Analogies may offer guidance, foresight (via hindsight), and intellectual shelter, but they can also be red herrings,

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024 11 Politics

Politics

promising preparedness for a profoundly different situation.

There are, nevertheless, portents of a proto- or pre-fascist situation. Fascism emerged as a way of resolving the contradictions and failures of liberal democracy and capitalism, by using violence and authoritarianism to restore order and stability. Grégoire Chamayou’s analysis of fascism, discussed here, shows how it adopted a form of liberalism that sacrificed democracy and rights for economic efficiency and security. This resonates with the present situation of neoliberal austerity and authoritarianism. Fascism paradoxically claims to be both above and against the state, while relying on its apparatus of violence and coercion to impose its will and eliminate its enemies.

Since the Nazi era, to a large extent grassroots anti-fascism and state-led anti-extremist measures have focused on incipient fascisms. In the state-led, anti-extremist version of this, the chief goal has been quashing wherever possible the traditional organisational form of the fascist group –violent, masculine, white, nationalist, racist, clean-shaven. In Australia, the swastika and some other fascist hate symbols have recently been banned, an indicator of anxiety about disaffected citizens exiting the political mainstream, if not exactly a convincing, root-and-branch attempt to deal with the growth of fascisms in our neighbourhood. (Remember the Australian-born Islamophobic Christchurch killer?)

Fascism may today be more visibly networked, but it was never as nationally rooted as it liked to pretend, always drawing lessons from a fascist international that included a genealogy in colonial regimes. Extending understandings of fascism from the ‘classical’ vision of the interwar fascisms that crystallised in Europe as a specific type of political regime, Toscano turns to anti-colonial thought, alongside radical Black intellectuals such as Angela Davis, W.E.B. Du Bois, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Cedric Robinson.

leader. More commonly, it appears in flocks of shitposting, or the stochastic terrorist violence of the young male shooter, or the insurgent candidate within desiccated democracies. These share old-fashioned fascism’s licence to persecute, deputising their violence to a dispersed cadre liberated to commit racist, sexist, and transphobic acts.

The postcolonial fascism of Modi’s India and the neocolonial fascism of Netanyahu’s Israel – and its strange anti-Semitic European bedfellows, including Viktor Orbán – are clear signs of this political ideology’s mercurial nature. Nevertheless, wherever it goes, we seem to find the familiar cod-scientific and culturally chauvinistic hierarchies to justify repression, violence, and ex termination.

Primo Levi said in the 1970s that every age would see the return of fascisms in new and different materialisations. It arrives with new content, stirring up new hatreds. It is a ‘scavenger’ ideology, as Toscano puts it. Among the materials being fed into the maw today are climate politics. These resonate with younger demographics, and the more intelligent far-right operatives have given their politics an eco-twist, leaving behind as fossils the climate deniers of an earlier generation.

Across the twentieth century and into the present, these critics and activists have seen the links where others refused to. It was the connection between fascist Europe and its presumed territories, for example, that saw Black solidarity campaigns against the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. In a speech given in 1936, as Hitler and Mussolini menaced Europe, Langston Hughes said that ‘fascism is a new name for that kind of terror the Negro has always faced in America’.

Mussolini clearly stated that colonialism was foundational for fascism, including the Italians’ brutal war against Libya in the 1930s, which also served as inspiration for the Nazis. Anti-colonial thinkers pointed out in the 1930s that European fascists had learned many of their techniques in colonial and slave settings over previous centuries – a ‘fascism before fascism’ that consolidated an imperialist, capitalist world-system along racial lines.

As Toscano argues, fascism today does not primarily take the form – if it ever did, beyond the prominent interwar examples – of the mass party, the street militia, and the charismatic

The stand-by fantasies of fascists – dom ination of women, nature, and racial inferiors – are being reimagined, particularly given the manifold failures of other responses to the planetary crisis. The recent international rise of ecofascism is worrying for Australia, given that the existing faultlines in our political geography align with the climate disasters that will happen with increasing regularity and force.

Yet such forecasting and prognostication about the future of fascism is problematic, as Theodor Adorno observed, in fitting terms, in a lecture on ‘Aspects of the New RightWing Extremism’ in 1967.

Perhaps some of you will ask me what I think about the future of right-wing extremism. I think this is the wrong question, for it is much too contemplative. This way of thinking, which views such things from the outset like natural disasters about which one makes predictions, like whirlwinds or meteorological disasters, this already shows a form of resignation whereby one essentially eliminates oneself as a political subject; it expresses a harmfully spectator-like relationship with reality.

If there is a problem with Levi’s truism, it is that he speaks like the weatherman or the seer. A response to fascism doesn’t need people to imagine themselves as meteorologists but as political agents capable of intervening in the social catastrophe that fascism at once fears, wills, and represents. g

Ben Gook is Lecturer in Cultural Studies at the University of Melbourne and the author of Divided Subjects, Invisible Borders: Re-unified Germany after 1989 (2015).

12 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024

Langston Hughes, 1939 (photograph by Carl Van Vechten/Granger - Historical Picture Archive/Alamy)

LEAD PROFOUND CHANGE AND HELP SOLVE OUR MOST URGENT ETHICAL CHALLENGES

STUDY A MASTER OF BIOETHICS

When it comes to advancements in medicine, technology, health and science, the future is now. However, progress comes at a cost. Bioethics is the answer to the seemingly unanswerable, and can help us solve our most urgent ethical challenges. Monash’s Master of Bioethics is designed to be truly multidisciplinary, bringing together bright and progressive minds from philosophy, medicine, biotechnology, law, journalism and science, to learn with and from one another. Don’t just think about it, change it.

Learn more about the Master of Bioethics

monash.edu/arts/study/MBioethics

Sorry tales

A study of collective biopolitics

Stephanie Collins

TThe Penitent State: Exposure, mourning, and the biopolitics of national healing

by Paul Muldoon Oxford

University Press

£83 hb, 335 pp

he recent past is replete with instances of sovereign states doing penance for wrongdoing. The Berlin Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), and Kevin Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations are just three examples that receive extended analysis in Paul Muldoon’s The Penitent State. On Muldoon’s telling, the concept of ‘biopolitics’ is central to explaining why these ‘penitent states’ work so hard to press our physical and emotional buttons, not just our intellectual or cognitive ones. Through institutions of atonement, the state is trying to clear a perceived blockage in perpetrators’ collective emotional system. It is trying to make us cry.

To understand why this happens, we need to understand biopolitics as encompassing all operations by the state on the human health of its populace. We must also view the modern state as operating under a distinctively Freudian assumption about human health: that guilt needs to be physically dispelled from the body via a process of catharsis or expungement. This includes when the body is a body politic. In public memorials, in truth commissions, and in parliamentary apologies, the state operates to ensure that the perpetrator-population’s guilt is duly expelled. The populace is then free to go on its way, relieved of the burden of its guilt, without feeling the need to reflect critically on its past, present, or future.

narrative’ (as Muldoon quotes Juno Gemes). Under the rubric of biopolitics, this purging is no accident. It is the point and purpose of state penance.

What about the predictable response that ‘we’ do not need to expel our guilt, because ‘we’ have nothing to be guilty for? Call this ‘the John Howard critique’. Muldoon nicely sidesteps this critique: his is a story about collective, rather than individual, biopolitics. It doesn’t matter that not all members of the perpetratorpopulace were perpetrators in a more literal sense. The guilt will spread like a virus through that population to the point where all carry the guilt just the same, so that all must have it exorcised.

Through institutions of atonement, the state is trying to clear a blockage in perpetrators’ collective emotional system

Muldoon’s biopolitical lens on state penance can be contrasted with at least three alternative lenses, which respectively concern legitimacy, ethics, and reflection. The legitimacy lens says penitent states are just greedily aiming to enhance their

Muldoon is not the first to suggest that state penance is more about alleviating perpetrator guilt than it is about doing right by those the state has actually wronged. Similar points were made by Indigenous Australian commentators in the wake of Rudd’s apology in 2008 (Muldoon notes Nicole Watson in particular). But Muldoon’s biopolitical tool kit explains why modern institutions of state penance take the precise form they do, that is, a form that sparks physical purging in the perpetrator-populace. At the Berlin Memorial, this purging is achieved via a set of massive spiralling stelae that draw the visitor ever deeper into the physical earth. In South Africa’s TRC, the purging was achieved via the widely watched televised displays of survivors’ raw emotional expressions. And in Rudd’s apology, the purging was achieved via the general sense that ‘we had all participated in a seminal catharsis in our personal and national

legitimacy, under the glare of social norms that support human rights. Muldoon sees this lens as overused by political scientists. The ethical lens says penitent states must be assessed by moral standards, specifically by the standard of whether the state is truly ‘sincere’ in its performances of remorse. Muldoon thinks moral philosophers over-emphasise this. And the reflection lens says penitent states are successful to the extent that they induce reflective soul-searching in their populace. Muldoon finds this lens at work in Ancient Athenian tragedy, where the audience was presented with state-based wrongdoing in a fictionalised and therefore distant form, facilitating the audience’s critical reflection on real-life practice, while allowing them to ignore all the guilt that comes with confronting a wrong that is actually

14 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024 Politics

Kevin Rudd on screen in Federation Square, Melbourne, 2008 (Virginia Murdoch/Flickr via Wikimedia Commons)

perpetrated by one’s state.

At times, Muldoon’s bioethical lens becomes blurred with the ethical one from which he is keen to distance himself. To be sure, Muldoon is not concerned with the sincerity of, say, the Berlin Memorial, the Rudd apology, or the South African TRC. But other ethical standards crop up throughout the argument. Muldoon worries that our modern institutions of state penance ‘deflect attention from the failures of the state’, or perform an ‘unforgiving exposure’ of victims, or render the state ‘perversely relieved of the responsibility to reflect on what happened’. These are clearly ethical or moralised assessments. Thus, Muldoon may be correct that institutions of state remorse function to expunge guilt from the body politic. But he implicitly acknowledges that this function is not the measure by which we should assess these institutions. To establish that bar, we must use an ethical lens that he explicitly eschews but implicitly adopts – though he doesn’t fully explain which ethical standards he employs or why.

At other times, the analysis is not concerned with any of the lenses outlined above. For example, the book’s discussion of Rudd’s apology mostly concerns whether it is even possible for

The spectre

The legacy and frailties of Robert Menzies

Patrick Mullins

BThe Menzies Watershed edited by

Zachary Gorman

Melbourne University Press $50 hb, 288 pp

Menzies versus Evatt

by Anne Henderson

Connor Court Publishing $34.95 pb, 235 pp

ernard Cohen’s satirical novel The Antibiography of Robert F. Menzies (2013) begins shortly before the 1996 election with the titular character stepping ‘through a breach in time’ to help his successors win government. But while John Howard’s double-breasted jackets and headland speeches initially soothe this ‘large and benevolent plasmic entity’, the revenant Menzies soon becomes frustrated by the emptiness and the clichés of 1990s politics. He breaks out of the parliamentary corridors to lumber across an Australia he barely recognises, becoming ever more gigantic and spectral – pursued all the way by a writer trying to wrestle him onto the page.

As though Cohen’s novel was reality, a bevy of scribblers have been attempting to replace the plump Edwardian laird of popular memory with a political master and visionary whose revived example is still relevant. There has been Howard’s Menzies Era (2014) and its television adaptation, Building Modern Australia (2016); a biography by Troy Bramston (2019) and a monograph by Scott Prasser (2019); collections on the Menzies legacy (2016) and compilations of his speeches and writings (2017, 2020); an

the sovereign state to apologise for breaking the moral rules, given that it’s the one that makes those rules in the first place. Here, we are deep in the weeds of social contract theory and its relationship to realism about moral standards. Muldoon makes a strong case for the idea that there is something paradoxical in the state saying ‘sorry,’ given its status as rule-maker. But the connection to his preferred biopolitical approach is not fully elaborated.

All of this is to say that Muldoon’s book encompasses much more than his own biopolitical framing suggests. The theorising far outstrips biopolitics, and the examples go well beyond the three listed above – including the Athenian Amnesty of 403BCE, Shakespeare’s take on Richard III, and Albert Camus’s novel The Fall. Muldoon hesitates to say anything too prescriptive about how state penance should operate or how it can be done better, but the reader is left in no doubt that these instances of state penance cannot be taken at face value. g

Stephanie Collins is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Monash University. Her most recent book is Organizations As Wrongdoers: From ontology to morality (2023). ❖

account of his religious faith (2021), and even a study that posited him as a forgotten figure (2021).

The most sustained effort in this antipodean Frankenstein-ing has been underway at Ming’s alma mater, the University of Melbourne, where the Robert Menzies Institute has paired a generally reputable program of symposia, fellowships, and public events with a more partisan celebration of the legacy of the man it terms ‘Australia’s greatest prime minister’. The principal channel for that celebration has been a four-volume series tracing his life, influence, and government.

Suspicions reasonably aroused by the origin of the volumes and some of their contributors can – mostly – be set aside. The first volume, The Young Menzies (2022), explored with insight its titular subject, and the second, The Menzies Watershed: Liberalism, anti-communism, continuities 1943–1954 (2023), is notable for its focus on a period of considerable change. In 1943–54, Menzies was more expedient, vulnerable, ruthless, and conflicted than his 1960s-era Emperor Penguin pomp might suggest; one of this volume’s qualities is its ready acknowledgment of this. Discussing policy shifts from the Labor government to Menzies, Tom Switzer notes the pragmatism of the Menzies government in its early years: far from dismantling everything the Curtin and Chifley governments had done, Menzies showed ‘little inclination to actually conquer the enemy territory’. The Coalition government certainly had its own policies, such as ending wartime economic controls, but, as David Lee notes in a chapter on economic management, the continuities with its predecessors were palpable and widespread. Communism was the principal exception: early in the 1940s, as current Human Rights Commissioner Lorraine Finlay writes, Menzies’ liberalism spurred his opposition to calls to ban the Communist Party. As the decade wore on, however, the strength of that liberalism was eroded by fear and by doubts that democracy could win with ‘one hand tied behind her back’. Even friendly critics were aghast at Menzies’ change of heart. As

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024 15 Politics

one asked, ‘Why oppose Satan if you are going to adopt his ways?’

Some adoption of enemy ways would be rewarded. As Billy Hughes bemoaned, the 1943 election had been a cyclone to the non-Labor parties: it exposed a sharp contrast with the strength of Labor’s formidable organisation. Persuading the leaders of the remnant non-Labor parties and groups to throw in their lot and form a nationwide party, to be led by a former prime minister who had left office unlamented in 1941, was no small task. Nicolle Flint’s claim that this was ‘Menzies’ miracle alone’ is unpersuasive bombast, but the invocation of a divine intervention speaks to the improbable future for the non-Labor parties in 1943. Who among them would have envisioned a return to government in only six years’ time? Who, in even their most fevered dreams, would have thought the Liberals would still be there, on the government benches, more than two decades later?

As editor Zachary Gorman writes, these were portentous years and there is much to be found in them that bears knowing about. While the many gaps in Watershed limit its utility, chapters such as Christopher Beer’s (on the effects of Menzies government policy on the NSW Central Coast electorate of Robertson) and Lyndon Megarrity’s (on international students in Australia before and after the Colombo Plan) are interesting and illuminating.

Also centred on these years is Anne Henderson’s Menzies versus Evatt: The great rivalry of Australian politics, which dwells on the parallel lives and battles of her titular subjects. While the similarities between Menzies and ‘the Doc’ are striking – stellar students at university, early leaders at the Melbourne and Sydney Bars respectively, entrants to federal politics who arrived seemingly on divine chariot – it is the differences of temperament and outlook that are most notable, particularly as their paths became increasingly intertwined. Much of the biographical material Henderson presents has been quarried elsewhere, but she adds to a clear portrait of both men an accessible account of the broader forces at work and enlivens her account further with spiky questions about received wisdom.

success at the referendum: while it convinced followers that he could be a leader, it also complicated Labor’s task of dispelling fears that it was susceptible to communist influence. Evatt’s sub-

H.V. Evatt’s opposition to the 1951 referendum to ban the Communist Party, for example, has typically been regarded as his finest hour, requiring him to withstand political expediency and enormous public pressure. Henderson undercuts that regard by pointing to the considerable advantages enjoyed by opponents of constitutional change and asks, considering those advantages, why the No campaign won with only 50.56 per cent of the popular vote. It is a worthwhile question, if somewhat churlish given that, six weeks before the vote, polls put support for the ban at seventythree per cent.

Henderson is also ambivalent about Evatt’s campaigning: she acknowledges the contrast between his considerable activity and Menzies’ languor, and agrees that hyperbole is inevitable in a campaign, but she is critical of Evatt’s invocations of Pastor Niemöller and the Nazis, dismissing these as ‘histrionic assertions’. She is clear-eyed, however, about the political consequences of Evatt’s

sequent disastrous handling of that task is related in bitter detail, though it edges out the rivalry with Menzies to the point that the 1955 and 1958 elections, where Menzies first began to take on an unassailable political supremacy, are dealt with perfunctorily.

In Cohen’s novel, the spectral Menzies is pursued right to the edge of the Australian continent. Stamping his foot on the rock to break it, he is, like Frankenstein, then carried away by the waves. Time is taking Menzies further and further away from modern Australia, but in his receding figure his frailties and flaws, his qualities and legacy, seem more visible and increasingly better understood. g

Patrick Mullins is a Visiting Fellow at the ANU’s National Centre of Biography.

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024 17 Politics

Sir Robert Menzies is installed as new Lord Warden of Cinque Ports, at Dover, 1966 (Keystone Pictures/Alamy)

The spectre of tribalism

Reflections on Israel, AIDs and identity politics

by Dennis Altman

‘Life would be infinitely happier if we could only be born at the age of eighty and gradually approach eighteen.’

Mark Twain

Last year I turned eighty. Vacillating between denial and celebration, I decided, with some trepidation, on the latter. It was thirty years since I had last had a big birthday party: this one needed to be special. I consoled myself that, old as I am, I am still younger than the president of the United States, Mick Jagger, and the pope.

The obvious site was Melbourne’s new Pride Centre, the $25 million building that occupies half a city block on Fitzroy Street, St Kilda, a five-storey curvaceous white fantasy with a rooftop view across the Bay. Guests entered through the massive foyer, with its grand staircase that could grace an opera house, and walked into the back hall, where a friend acted as DJ, spinning a series of CDs that reflected half a century of favourite music. No Mick Jagger, but David Bowie, Joan Armatrading, Lou Reed, Janis Joplin – and Mahler both to begin and end the evening.

Friends rallied to help plan the evening. Two of them constructed extraordinary cakes from brownies and fruit, and the evening included a wonderful singer and several speeches. My sister told a story from our past that was new to me, and my two best women friends performed a double act, pointing out that if you needed to find me you just looked for the cutest young man in the room. By chance he was standing next to me at the time.

I expected to feel let down after the party; in fact I felt rejuvenated. But mine is an age where there are more ghosts in the room than actual people, above all that of my long-term partner, who died of lung cancer ten years ago. I am most aware of Anthony when I see changes to the city skyline that he would no longer recognise; there is a gaping construction hole at St Vincents Hospital where he died

in intensive care, the sight of which produces a shudder whenever I drive past.

Each year another link to Anthony fades. We lived with five cats over the years we were together, and the last, called CJ after Allison Janney’s character in The West Wing, died while I was in Europe in 2022. When Anthony was ill she would lie on him for hours, purring; now she is buried under a rose bush next to the one in his name. Losing a partner brings both deep grief and trivial problems: suddenly there is too much bread, and turning the mattress alone is a challenge. Anthony was fifteen years younger than me; it felt strangely perverse that he was the one who died.

I am one of a generation of gay men who are survivors, who lived through the fifteen terrible years between the onset of AIDS and the emergence of effective treatments. Those years have hollowed out a community, just as war does, or natural disaster. For three decades, AIDS was the dominant passion of my life, reflected in both community and academic work. I was never a frontline worker, but the struggle to build political support to combat the epidemic took me across the world, from a shanty town in Johannesburg to a helicopter ride over the Swiss Alps in the company of extraordinary activists, scientists, and people living with HIV.

Those awful years should have prepared us for the time when every week someone familiar passes away. One of my earliest AIDS memories is of visiting a former student at Santa Cruz who was in hospital in the last stages of his life. ‘It’s not fair,’ he said bitterly. ‘I haven’t had my life yet.’

However we parse it, eighty is old. Yes, Verdi wrote his last opera at that age, and Margaret Atwood and Helen Garner continue to write in their eighties. It would be dishonest to deny that the spectre of death lurks, that one becomes increasingly aware that every experience might be the last. Nothing shocked me more in thinking about my age

18 AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024 Commentary

than realising that someone aged eighty in the year I was born was alive before the end of the US Civil War and the first telephones.

Ageing also brings with it a sense of increasing irrelevance, despite the obligatory calls to honour our elders. As our health demands more and more attention by specialists, they in turn seem younger each year. The world moves on, leaving us increasingly nostalgic for what no longer exists in a world seemingly ruled by smart phones and social media. Postcards carrying exotic stamps no longer arrive from friends overseas; street directories and phone books become a distant memory. My childhood in Hobart was punctuated by the arrival of the evening Melbourne Herald; now I am one of the dwindling number of people who read a print newspaper over breakfast.

Yet if each generation slays its fathers, it tends to honour its grandparents. In that twilight period when our memories become a new generation’s history, I am increasingly asked to talk about the emergence of gay liberation half a century ago. During a small event at a queer bookstore in New York, I upset my interlocuter, a charming guy in his twenties, when I said I doubted that Stonewall had meant much outside the United States.

At least in the cities, the Australia I grew up in has retreated to old film clips and documentaries. The Saturday before Christmas I took the train to the far west of Sydney to be with Anthony’s family, sharing a carriage with a cheerful group of young women who had just come from a Palestinian rally, some in head scarves and sharing packets of supermarket chips. The shopfronts as we passed through Lidcombe, Granville, and Harris Park were a mix of languages and alphabets, Vietnamese and Ethiopian restaurants set amidst furniture warehouses and old Irish pub fronts. I love what Australia has become; I mourn the fact that, despite our much-vaunted multiculturalism, a small and respectful step towards Indigenous reconciliation was defeated in a popular vote.

much more complex history of dispossession and survival.

Hobart today is full of chic coffee bars and Asian restaurants; when I grew up there were two Chinese restaurants in the entire city, and a friend of my mother’s served traditional afternoon teas in a small café in the narrow Criterion Lane. Several passers-by look familiar, but perhaps I see traces of their grandparents in the faces of passing adolescents. Bodies, too, have changed: the young are taller, and there is growing obesity alongside gym-toned buffness.

Particularly for women, there are far greater options than for those of my generation. When I was at school, most girls who went on to further study would become either teachers or nurses, and the assumption was that their careers would end with

marriage. There were no women bank tellers, newsreaders or airline pilots, though we boasted the first woman federal minister, Tasmania’s Enid Lyons. She, however, only entered politics after the death of her husband, Prime Minister Joseph Lyons.

Earlier this year, I was in Hobart to speak at an event in support of queer asylum seekers. I left Hobart on my twenty-first birthday to go to graduate school in the United States, and since then have only visited for short periods. No Australian city is as shaped by its geography, nestled as it is between river and mountain, but Hobart, too, has changed, has become less white, more cosmopolitan, wealthier. The museum where schoolchildren were taken to see the preserved remains of Truganini, ‘the last Tasmanian’ – the descendants of Indigenous Tasmanians were effectively whitewashed out of existence for almost a century – now pays due respect to the

Much of my life has been shaped by the stroke of luck that took me to New York at the birth of the American gay liberation movement. I had already been a lecturer at Monash University in the late 1960s, where an extraordinary group of honours students introduced me to the ideas of Herbert Marcuse. In 1969, I moved to Sydney, largely because that seemed the easiest place to be gay in Australia. With a generosity long gone from the academic world, I was given six months’ leave at the end of my first year and went to New York without a clear project in mind.

I needed somewhere to live and found a room in a large apartment in the East Village, then a place of some danger. (I was once held up at gunpoint by someone who, I suspect,

AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW MARCH 2024 19 Commentary

The author in Rio, 1979

was more nervous than me and who fled after taking my money.) The apartment belonged to a painter named Adolph, whose images of feet fascinated the writer Paul Goodman when he visited. Adolph offered his place for meetings of the new gay liberation paper, Come Out! Suddenly a young Australian found himself in the midst of the new movement, and within a few months determined to write about it. Through luck, perseverance, and the help of rock-star reporter Lillian Roxon, I found a publisher for what became my first book, Homosexual: Oppression and liberation (1971).

My life has been shaped by the luck that took me to New York at the birth of the American gay liberation movement

That book has shaped much of my career for half a century, even though I have subsequently written over a dozen more. In April I will speak about it at several universities in northern Italy, although I find rereading Homosexual brings a mixture of nostalgia and embarrassment. I spent much of the decade after it appeared fantasising about life as a writer, which led to my resignation from Sydney University and five years living off my wits in New York and Santa Cruz, in the period that encompassed both the Reagan presidency and the onset of AIDS. Ninety per cent of writing is solitary, but the adrenalin comes from the other ten per cent; the radio interviews, the panels at writers’ festivals, launch parties, and publishers’ lunches, now sadly less lavish for those of us who are not bestselling authors.

But I had no talent as an expatriate, and caution drew me back to academia. Again luck intervened; I had no intention of going to Melbourne, but La Trobe University proved to be a remarkable place to work, with a culture that allowed freedom for the sort of intellectual freewheeling that is increasingly impossible for academics nowadays. One of the proudest moments of my time at La Trobe where, after a period teaching at Harvard, the best students in my course on American politics were equivalent to those I had encountered in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Health and finances permitting, retirement is the perfect time to become what one has always fantasised. This led me to write a murder story.

I had long thought that a gay sauna would be the perfect venue for a murder. Lockdown walks with my friend Tom produced a setting and characters, and suddenly I was writing the book. It was not until I was close to the end that I realised the person Tom and I had thought was the killer was not.

The market for murder stories is flooded and none of the mainstream publishers I had worked with was interested. Luckily, I knew a small indie Melbourne publisher, who proved to be a remarkable editor and designer; we would meet for coffee and he would explain to me choices around paper quality and font size, something that my other publishers had never shared with me.

Nothing has been more fun in the past decade than

writing and then talking about Death in the Sauna. It took me to some of my favourite bookstores, including a panel event at Hares & Hyenas in Melbourne with three of the guys who work at the city’s largest gay sauna. It brought me into conversation with writers such as Andrea Goldsmith, Alice Echols, and George Haddad. I met unexpected readers, like the young man at Brisbane’s Avid Reader who said he was there on a mother/son date. ‘We both loved your book,’ he said. ‘But I had to explain what amyl was to my mother.’

There is a growing stack in my study of my writings and conference programs, some of which even I have long forgotten. Each year produces its own memorabilia. When Anthony and I travelled we always bought little cats – in wood, stone, glass, even plaster – and now fifty or so sit on the mantelpiece, though I have long forgotten where each came from. Most encumbering is my very large stamp collection, now more than a hundred years old. When my father came as a refugee from Vienna in 1938, he brought his collection with him. Since then it has swollen and now includes about 100,000 stamps, almost all of which are valueless.

My father encouraged me to collect, and through stamps I learned about history and geography, to be familiar with exotic places like the Territory of the Afars and the Issas, and Heligoland. With Anthony I would hunt for stamp shops when we travelled. I loved the big outdoor stamp markets of Paris and Madrid. Now the Paris market, a line of stalls at the foot of the Champs-Élysées, has shrunk to a couple of disconsolate sellers who sit Godot-like waiting for the occasional visitor.

I have always been drawn to collecting; as a teenager I sought out airline timetables, then glossy brochures with tantalising images of a world far beyond Hobart. I still have a carton of matchbooks from the days when they were provided at every bar and restaurant. Collecting, a woman friend once suggested to me, is a rather masculine attempt to master the world, but it is also a record of one’s own life, and hard to discard. If as Milan Kundera wrote ‘nostalgia is the suffering caused by an unappeased yearning to return’, our collections are ways to appease that loss.