9 minute read

BLAZING THE HIGH TRAIL OVER TEXAS

AUTHENTIC PERSON

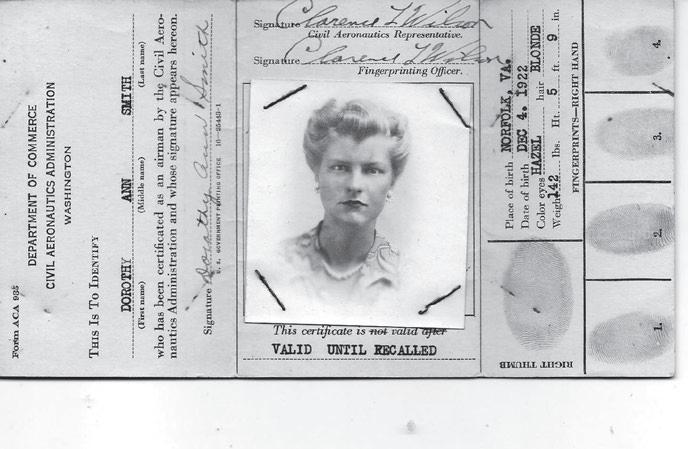

DOROTHY ANN SMITH LUCAS, WOMEN AIRFORCE SERVICE PILOT

Advertisement

By Bob McCullough

As the crisis of World War II swept the nation, Dorothy Ann Smith Lucas—affectionately known as Dottie—and 1,102 other Women Airforce Service Pilots(WASP) of the Greatest Generation— didn’t realize they would serve as trailblazers for women in aviation.

Today, at age 97, Dottie Lucas modestly dismisses what the WASP did to open cockpits and space shuttles for women. “It was a very patriotic time,” says Lucas, who had two brothers in the military, one of them an Army Air Forces navigator and the other in the Navy. “I just wanted to do something to help the war effort.” After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, qualified male pilots were desperately needed for combat roles, yet tasks like ferrying newly assembled planes to military bases still had to be accomplished. Twenty-eight already licensed civilian women pilots led by Nancy Love stepped up to fill this need and became the nation’s first female flying unit—the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron. This outfit ultimately merged with the Women’s Flying Training Detachment established by Jacqueline Cochran on August 20, 1943, to form the WASP.

More than 25,000 women applied to join the WASP; 1,830 were accepted, and 1,074 earned their wings at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas, before the program ended December 20, 1944. Their flight jackets proudly displayed the WASP mascot, Fifinella, a winged female gremlin wearing goggles and boots that suppos edly possessed magical powers. The character emanated from British author Roald Dahl’s The Gremlins and Walt Disney’s creative graphic design.

“One day in early 1943, my friend Margaret told me about an organization that was looking for female pilots,” Lucas recalls. “We learned the age limit was from 21 to 35 years and that you had to have thirty-five flight hours to apply for admission to WASP. You also were required to be of good moral character, complete a personal interview with supervisors, and pass the rigorous Army physical for all military pilots.”

LAUNCH Dorothy Ann Smith began private pilot training in Maryland in 1943.

Photographs provided by Dorothy Ann Smith Lucas

Accumulating the requisite hours of flight time proved to be quite challenging. Lucas worked at the War Department on Constitution Avenue in Washington, D.C., during the week, attended George Washington University at night, and took flying lessons on weekends, thanks to a $300 loan from her mother. “I decided on my own that I wanted to learn to fly,” Lucas says. “Margaret and I had to drive fifty miles to Frederick, Maryland, to take flying lessons, which were very expensive. We had to make that long drive because no planes were permitted to fly within a fifty-mile radius of the Capitol.”

Lucas qualified for admission to the WASP program, but Margaret dropped out at the last minute. Suddenly, Lucas found herself at Avenger Field in windswept Sweetwater, far different surroundings than her native Norfolk, Virginia, and work environment in D.C. “It was my first time in Texas, a very different experience but very interesting for me,” she remembers. “But I always enjoyed meeting new people and going to new places. It was pretty amazing.” Avenger Field, established in 1940 to train pilots under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Lend-Lease Program, initially functioned as a training location for British and Canadian pilots aspiring to serve in the Royal Air Force. When the WASP program moved there in May 1943, Avenger became the only allfemale flight training base in U.S. military history. There, in the high and wide-open Texas skies, WASP recruits learned to fly the Army way.

SUITED UP Smith, at far right, with WASP colleagues at Avenger Field in Sweetwater.

Photos provided by Dorothy Ann Smith Lucas.

SUITED UP Smith ready for flight training.

Photos provided by Dorothy Ann Smith Lucas.

Lucas and other WASP recruits spent thirty weeks in training. They put in 210 hours of flight training and 393 hours of ground school, covering topics like navigation, aircraft mechanics, meteorology, first aid, Morse code, and military conduct. She trained in the PT-17 Stearman biplane, the BT-13 Valiant, and the PT-19 Fairchild.

Dottie during flight training (center) with flight commander Mr. Poole, left, and Mr. Robertson, right.

Photograph provided by Dorothy Ann Smith Lucas.

Tragedy struck the day before Lucas was scheduled to make her first solo flight. She received word that her brother in the Army Air Forces had been killed in a plane crash in England, and in that moment of grief, she had second thoughts about continuing her WASP training. But her WASP sisters gave her support and encouragement that led to a successful solo and made her “even more determined to become a WASP.”

Dottie upon her WASP graduation.

Photos provided by Dorothy Ann Smith Lucas.

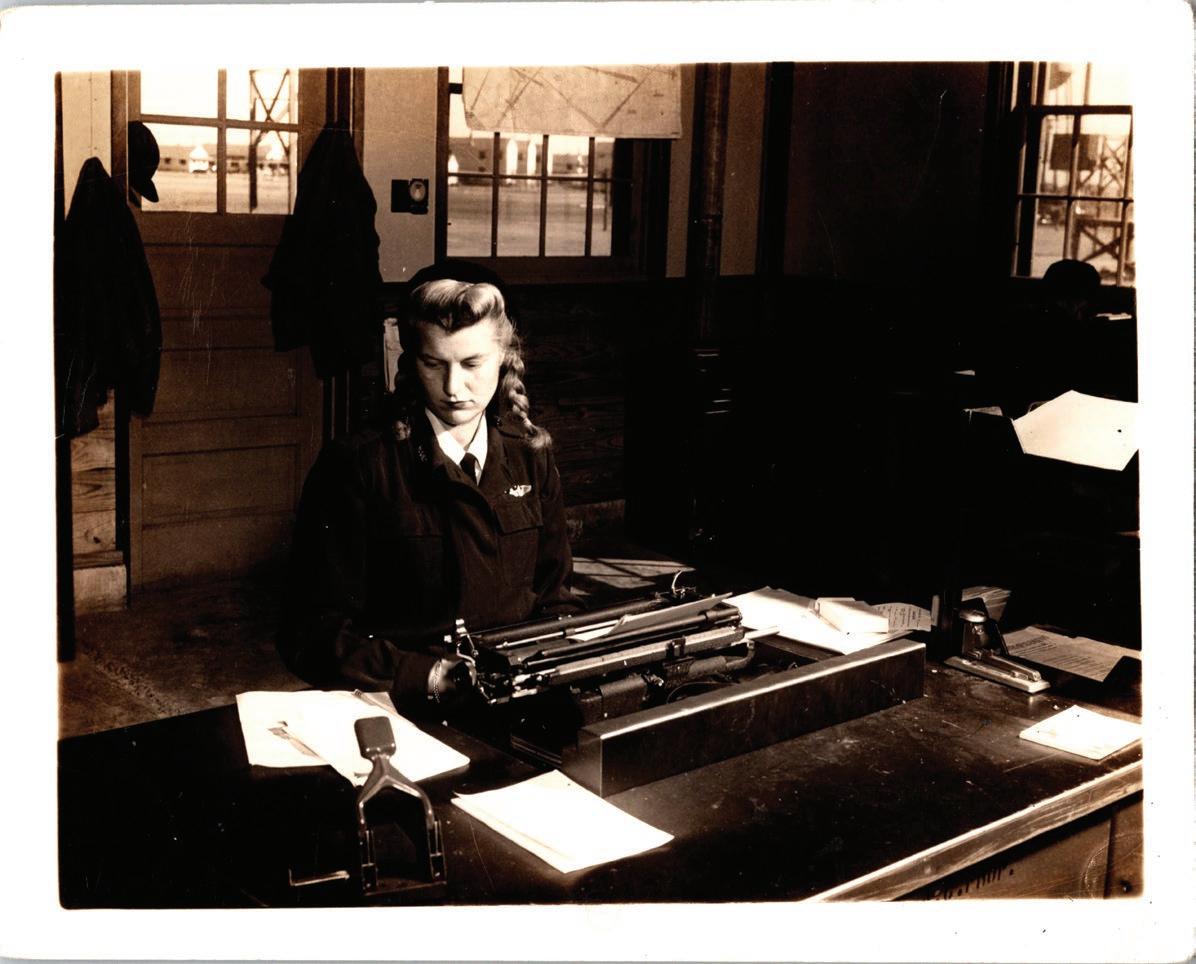

After graduation with WASP Class 1944-W-7 in September, Lucas was assigned to the gunnery squadron at Moore Field in Mission, Texas. There, her primary duty was to tow targets for male flying cadets.

“Our tow ships were AT-6 Texan advanced two-seat trainers,” Lucas explains. “There was a young enlisted man in the back seat operating the cable. On the end of the cable was a large flag, the target. The cadets undergoing gunnery training made passes at the target from their planes. After these sessions, I flew to the auxiliary airfield not far from Moore Field, where I slowed the plane. The young man in back released the target and reeled the cable back up into the plane. I then landed so he could jump out, retrieve the flag, and put it in the back seat. We then took off for the main airfield, and that was the end of a gunnery session, about an hour and a half in all.”

MISSION, TX Smith at Moore Airfield Office taking care of paperwork before taking to the air towing targets.

Photograph provided by Dorothy Ann Smith Lucas.

—DOROTHY ANN SMITH LUCAS “WHAT’S BETTER THAN FLYING THE AT-6?”

GOING TEXAN Smith turns a propeller (left) and boards the renowned AT-6 Texan at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, April 1944.

Photograph provided by Dorothy Ann Smith Lucas

Lucas, who never feared flying, didn’t encounter any stray bullets, but on one occasion smoke filled her cockpit. She radioed the control tower, which advised her either to land or bail out. She opted to land, but recalls with a grin, “I think the plane was still taxiing when I jumped out.” (In all probability, the smoke resulted from a minor engine-oil leak.)

While towing targets at Moore Field, she met and dated a young instructor pilot, Captain A. T. Lucas. “One day I was preparing to land at the auxiliary airfield when I saw his plane on the ground,” she says. “He was watching his cadets shoot takeoffs and landings. I really wanted to make a smooth landing, but I leveled off too high and bounced in. Was my face red! That was the worst landing I ever made, but you know what? He married me anyway!”

After World War II, Lucas’s husband continued an Air Force career that took the family—including children Jana, Helen, Melanie, Tom, and Marnie—to bases in Germany, the Philippines, and various locales across the U.S. After military service ended, the Lucases settled in Austin and ultimately moved to San Antonio, where Dottie now lives.

The trailblazing accomplishments of Lucas and other WASPs continue to elicit praise from a grateful nation at the National WASP World War II Museum at Avenger Field on Sweetwater’s western outskirts. The move to establish the museum took off in 2002, and on Memorial Day 2005, the museum held its grand opening with 29 WASP alumnae in attendance. They placed their handprints in cement and etched their signatures.

The thirty-five-acre museum complex includes old runways, taxiways, and two hangars—the new No. 1, a replica of the original main hangar, and Hangar No. 2, built in 1929 as part of Sweetwater Municipal Airport and used by WASP in 1943–44. The WASP barracks, administration building, classrooms, and control tower burned in 1951. In May 2017, the Hangar No. 1 replica opened in time to host the annual WASP Homecoming on the Saturday before Memorial Day. A spacious Memorial Plaza connects the two hangars, looking out onto the airfield where the ashes of thirteen of the program’s former pilots have been spread.

“The museum has numerous exhibits, including four of the five planes used in WASP training,” says Carol C. Cain, associate director. “The WASP handprints exhibit is a very emotional one; you actually put your hand into theirs. But it’s not the actual artifacts and exhibits that exemplify the museum. It’s the character traits of those women aviation pioneers—service, courage, dedication, loyalty, patriotism and sacrifice—that make the museum so very exceptional.”

Cain estimates approximately 500 people a month take time to visit and learn about these phenomenal female pilots. Meanwhile, planning continues for an ambitious, climate-controlled expansion of Hangar No. 1 that will include educational areas, a re-creation of the control tower, interactive exhibits, and additional display space for WASP artifacts. The museum archives, which already contain 35,000 items, welcome additional WASP memorabilia, artifacts, and stories. Special events throughout the year spotlight individual pilots as well as feature conversations with notables in aviation.

The museum’s ongoing mission is to give WASP credit that’s long overdue and to preserve their legacy. Their accomplishments are truly impressive. For example, at one time or another, a WASP flew all 77 types of planes in the Army Air Forces inventory. They delivered 12,000 aircraft from factories to operational units. They logged duty at 126 air bases across the country. They flew more than 66 million miles. They freed up hundreds of male pilots for combat. And much of what they did was paid for out of pocket.

“Because the WASP were paid under Civil Service and not part of the military, they received no military benefits or insurance,” Cain says. “They had to pay their way to Avenger Field, and their way home when the program was deactivated. The thirty-eight who were killed in service to their country could have no American flag on their coffin and could not be buried in military cemeteries, and their families could place no Gold Star in their windows.”

But persistent pressure on lawmakers resulted in changes. In 1977, WASP were accorded military status, and in 2002, the Army granted WASP military funeral honors. Seven years later, President Barak Obama signed legislation that led to presentation of the Congressional Gold Medal to WASP in March 2010. This lofty honor is awarded to persons “who have performed an achievement that has an impact on American history and culture that is likely to be recognized as a major achievement in the recipient’s field long after the achievement.”

“In addition to being an elite corps from the standpoint of skills, ability and experience, the WASP were guinea pigs,” Cain contends. “No program like this had ever been tried before. The future of women in military aviation hung on how the women performed professionally and conducted themselves morally and socially.”

Lucas agrees. “Not only did WASP prove that women could fly military aircraft as well as their male counterparts,” she says, “but they also established a firm foundation for women in aviation.”

FINALLY Dorothy Ann Smith Lucas was among the 300 living WASP who were presented with the Congressional Gold Medal in March 2010.

Pictured with Dottie is her military escort for the occasion, MSGT Mitchell.

Photograph provided by Dorothy Ann Smith Lucas

Determined to do their part to help win World War II, volunteer female pilots from across America flocked to Sweetwater and blazed a trail high up in Texas skies for thousands upon thousands of women who would follow.

National WASP World War II Museum, 210 Avenger Field Rd., Sweetwater, TX 79556; (325) 235-0099; waspmuseum.org; Tuesday–Saturday 10 am–5 pm; Sunday 1–5 pm; free admission